Abstract

Background

Central nervous system (CNS) relapse of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is associated with a dismal prognosis. Here, we report an analysis of CNS relapse for patients treated within the UK NCRI phase III R-CHOP (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone) 14 versus 21 randomised trial.

Patients and methods

The R-CHOP 14 versus 21 trial compared R-CHOP administered two- versus three weekly in previously untreated patients aged ≥18 years with bulky stage I–IV DLBCL (n = 1080). Details of CNS prophylaxis were retrospectively collected from participating sites. The incidence and risk factors for CNS relapse including application of the CNS-IPI were evaluated.

Results

177/984 patients (18.0%) received prophylaxis (intrathecal (IT) methotrexate (MTX) n = 163, intravenous (IV) MTX n = 2, prophylaxis type unknown n = 11 and IT MTX and cytarabine n = 1). At a median follow-up of 6.5 years, 21 cases of CNS relapse (isolated n = 11, with systemic relapse n = 10) were observed, with a cumulative incidence of 1.9%. For patients selected to receive prophylaxis, the incidence was 2.8%. Relapses predominantly involved the brain parenchyma (81.0%) and isolated leptomeningeal involvement was rare (14.3%). Univariable analysis demonstrated the following risk factors for CNS relapse: performance status 2, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, IPI, >1 extranodal site of disease and presence of a ‘high-risk’ extranodal site. Due to the low number of events no factor remained significant in multivariate analysis. Application of the CNS-IPI revealed a high-risk group (4-6 risk factors) with a 2- and 5-year incidence of CNS relapse of 5.2% and 6.8%, respectively.

Conclusion

Despite very limited use of IV MTX as prophylaxis, the incidence of CNS relapse following R-CHOP was very low (1.9%) confirming the reduced incidence in the rituximab era. The CNS-IPI identified patients at highest risk for CNS recurrence.

ClinicalTrials.gov

ISCRTN number 16017947 (R-CHOP14v21); EudraCT number 2004-002197-34.

Keywords: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, rituximab, central nervous system, relapse

Introduction

CNS relapse is a devastating complication of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) associated with a median survival of 2–5 months [1]. The risk appears to be less in the rituximab era [2, 3]; however, the data are conflicting, with a decreased incidence in some [4–9] but not all reported series [10–13].

Chemoprophylaxis frequently with IT or IV MTX, is a longstanding strategy aiming to reduce the risk of CNS recurrence in DLBCL; however there is a risk of associated toxicity and limited evidence of efficacy. As the reported incidence of CNS relapse in the rituximab era in the absence of prophylaxis is 5.4% [10] administration is currently limited to high-risk patients.

Several risk factors for CNS recurrence have been reported including involvement of various extranodal (EN) sites by lymphoma at baseline, involvement of >1 EN site of disease [alone or in combination with a raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level], as well as a high-intermediate/high-risk International Prognostic Index (IPI) score, which are well-summarised by McMillan et al. [2]. In addition, several biomarkers including the activated B-cell (ABC) subtype of DLBCL [14], dual expression of MYC and BCL-2 by immunohistochemistry [14], or MYC or ‘double-hit’ rearrangement [15] are associated with increased risk.

Recently, the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL) reported a six-factor prognostic model, the CNS-IPI, incorporating the five IPI factors and presence or absence of kidney and/or adrenal gland involvement to determine the risk of CNS relapse for patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma. This model stratified patients into three risk groups for CNS relapse at 2 years: low [0–1 factors: 0.6%; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0% to 1.2%]; intermediate (2–3 factors: 3.4%; 95% CI, 2.2% to 4.4%) and high risk (4–6 factors: 10.2%; 95% CI, 6.3% to 14.1%) and was subsequently validated in an independent population-based cohort of R-CHOP-treated patients with DLBCL from the British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA) [16].

Here, we report an analysis evaluating CNS relapse for patients enrolled within the prospective randomised UK NCRI R-CHOP-14 versus 21 trial, including an evaluation of the CNS-IPI within this cohort and data regarding delivery of prophylaxis.

Patients and methods

The phase III randomised R-CHOP 14 versus 21 trial compared R-CHOP administered 2-weekly versus 3-weekly in the first-line treatment of DLBCL. A total of 1080 patients aged ≥18 years with previously untreated bulky stage I–IV DLBCL were enrolled at 119 centres across the UK between March 2005 and November 2008. We previously reported that the primary end point of superior overall survival (OS) of R-CHOP-14 compared with R-CHOP-21 was not met, and that R-CHOP-14 was not superior to R-CHOP-21 for progression-free survival, response rate or safety [17]. Patients with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) were not excluded from trial participation and we recently reported our outcomes for this subgroup of patients [18].

In accordance with the study protocol administration of CNS prophylaxis (12.5 mg IT MTX) with the first three cycles of treatment or according to local guidelines) was at the discretion of the local investigator, but recommended as per protocol for patients with involvement of bone marrow, peripheral blood, nasal/paranasal sinuses, orbit and testis. Details of CNS prophylaxis were retrospectively collected from participating sites using case report forms.

The study database was interrogated to identify all cases where the CNS was documented as a site of relapse at initial disease progression. To ensure that all cases were captured where progression was reported local investigators were also contacted retrospectively to determine if the CNS was a site of involvement. Where a case of CNS relapse was identified investigators were asked to specify the site(s) involved.

The primary end point of this analysis was to determine the incidence of CNS relapse. Progression-free survival and OS were calculated from the date of registration, censored at the date last seen, and analysed using Kaplan–Meier method.

Univariable (UVA) and multivariable (MVA) Cox regression analyses were performed to investigate the risk factors for CNS relapse. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the demographics between the following groups: group 1 (disease-free, n = 795), group 2 (systemic relapse, n = 264) versus group 3 + 4 (CNS relapse (n = 21: non-isolated n = 10, isolated n = 11).

The following parameters were assessed: sex, age (≤60 versus >60 years), WHO performance status (PS) (<2 versus 2), stage (I/II versus III/IV), bulky disease >10 cm (present versus absent), B symptoms (present versus absent), elevated LDH (present versus absent), IPI (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), >1 EN (present versus absent), presence of a ‘high-risk’ EN (bone, bone marrow, breast, kidney, orbit, nasal/paranasal sinuses, epidural space, peripheral blood and testis) (present versus absent), trial arm (R-CHOP-14 versus R-CHOP-21), CNS prophylaxis (yes versus no), cell-of-origin (COO) according to the Hans [19] algorithm (germinal centre B-cell (GCB) versus non-GCB subtype), BCL 2 translocation by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) (present versus absent), BCL 6 rearrangement by FISH (present versus absent), MYC rearrangement by FISH (present versus absent), ‘double-hit’ by FISH (present versus absent), MIB1 (<90 versus ≥90), MIB1 (<80 versus ≥80), COO determined by gene expression profiling (GEP) (GCB versus ABC versus Type III/unclassified).

The CNS-IPI was then applied to our cohort to investigate the incidence of CNS relapse according to CNS-IPI risk group.

Results

Key baseline characteristics for the entire trial cohort are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key baseline characteristics for the R-CHOP 14 versus 21 trial cohort (n = 1080) and for patients with CNS relapse (n = 21)

| R-CHOP 14 versus 21 cohort | Patients with CNS relapse | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 1080 | N = 21 | |

| Median age (range), years | 61 (19–88) | 59 (38–78) |

| Age ≤60 years | 476 (44.1%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Age >60 years | 604 (55.9%) | 10 (47.6%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 582 (53.9%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| Female | 498 (46.1%) | 10 (47.6%) |

| Performance status | ||

| 0 | 544 (50.4%) | 9 (42.9%) |

| 1 | 392 (36.3%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| 2 | 144 (13.3%) | 8 (38.1%) |

| Stage | ||

| I (bulky) | 79 (7.4%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| II | 323 (30.1%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| III | 317 (29.5%) | 4 (19.0%) |

| IV | 355 (33.1%) | 13 (61.9%) |

| Bulky disease | 533 (49.5%) | 12 (57.1%) |

| B symptoms | 489 (45.3%) | 12 (57.1%) |

| Elevated LDH | 701 (64.9%) | 18 (85.7%) |

| >1 site of extranodal disease | 296 (27.4%) | 14 (66.7%) |

| IPI score | ||

| 0 | 83 (7.7%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| 1 | 233 (21.6%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| 2 | 306 (28.3%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| 3 | 279 (25.8%) | 6 (28.6%) |

| 4 | 154 (14.3%) | 9 (42.9%) |

| 5 | 25 (2.3%) | 1 (4.8%) |

| MYC-rearrangement (N = 359) | 36 (10.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Double-hit-rearrangement (N = 354) | 16 (4.5%) | 0 (0%) |

Case report forms outlining CNS prophylaxis details administered on study were returned in 984/1080 (91.1%) cases, with data missing for 96 cases. A total of 177/984 patients (18.0%) received CNS prophylaxis within the trial. The type of prophylaxis administered was IT MTX (163/177), IV MTX (2/177), IT MTX and IT cytarabine (1/177) and prophylaxis-type unknown (11/177). Table 2 shows the proportion of patients receiving CNS prophylaxis by EN sites of involvement at baseline.

Table 2.

Administration of CNS prophylaxis and incidence of CNS relapse according to sites of DLBCL involvement at baseline

| Site of lymphoma involvement | N (%) | N (%) with | N (%) with |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS prophylaxis | CNS relapse | ||

| Bone marrowa | 101 (9.4) | 42 (41.6) | 6 (5.9) |

| Peripheral blooda | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA |

| Nasal/paranasal sinusesa | 6 (0.6) | 6 (100) | 1 (16.7) |

| Orbita | 2 (0.2) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) |

| Testisa | 14 (1.3) | 10 (71.4) | 0 (0) |

| Bone | 63 (5.8) | 29 (46.0) | 3 (4.8) |

| Breast | 17 (1.6) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (11.8) |

| Epidural space | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA |

| Kidney and/or adrenal gland | 69 (6.4) | 19 (27.5) | 4 (5.8) |

Administration of CNS prophylaxis was at the local investigator’s discretion but recommended if there was involvement of these sites at baseline as per protocol.

Twenty-three potential cases of CNS relapse were identified. Of these, two were excluded following discussion with the local investigator due to (i) presence of a spinal mass which did not penetrate the dura mater and (ii) CNS relapse occurred subsequent to initial disease progression. At a median follow-up of 6.5 years, the number of confirmed cases of CNS relapse was 21/1080 (1.9%), including one patient from the previously reported PMBL cohort. Over half the events were isolated (n = 11), with the remainder occurring in association with recurrence of systemic disease (n = 10); and the majority (14/21) occurred in the first-year following study registration. The incidence of CNS relapse was 2.0% (16/807) if prophylaxis was not administered and 2.8% (5/177) for those who received prophylaxis, or 2.5% (4/163) for patients who received IT MTX.

Baseline characteristics for patients with CNS relapse are shown in Table 1 and supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Data on molecular subtyping (Illumina DASL® platform) were available for 4/21 patients classified as GCB n = 2, ABC n = 1 and type III/unclassifiable n = 1 subtypes accordingly. CNS relapse predominantly involved the brain parenchyma (17/21, 81.0%), for 14/17 this was the only site of CNS relapse, 2/17 had concurrent spinal cord involvement and 1/17 had concurrent leptomeningeal infiltration. Three patients (3/21, 14.3%) had isolated leptomeningeal involvement and for 1 patient (1/21) CNS relapse was diagnosed on clinical grounds, following presentation with a facial nerve palsy and arm weakness in association with increased protein in the cerebrospinal fluid.

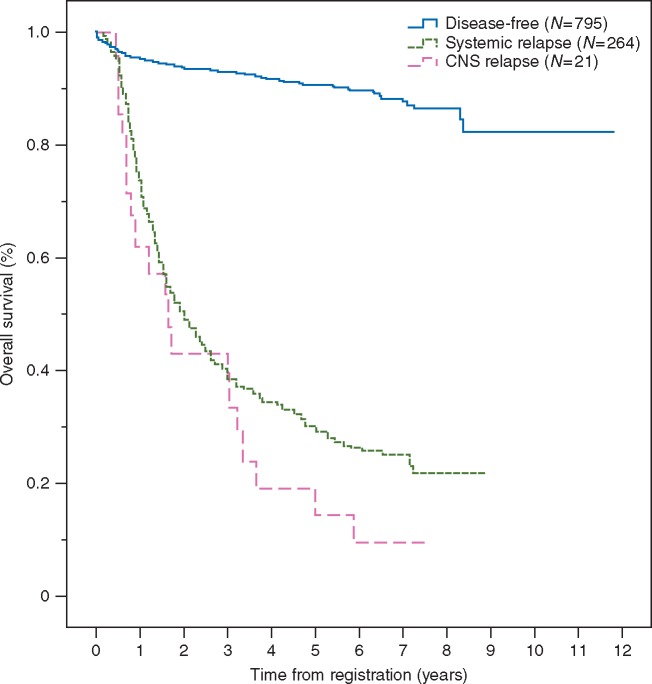

The median time to progression for a CNS and systemic relapse was 8.1 months (95% CI, 1.0–15.1), and 10.9 months (95% CI, 9.2–12.6), respectively. OS from study registration comparing relapse-free versus systemic relapse versus CNS relapse patient groups is shown in Figure 1. The median OS following a diagnosis of CNS relapse was 3.5 months (95% CI, 0.1–6.9) and 7.7 months (95% CI, 6.0–9.4) following a systemic relapse.

Figure 1.

Overall survival from study registration.

Significant risk factors for CNS relapse by UVA were WHO PS 2 (P = 0.001), elevated LDH (P = 0.042), IPI (P = 0.004), >1 EN site of disease (P < 0.001) and presence of a ‘high-risk’ EN site (P = 0.001) (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). No factor remained independently significant in MVA based on these 21 cases.

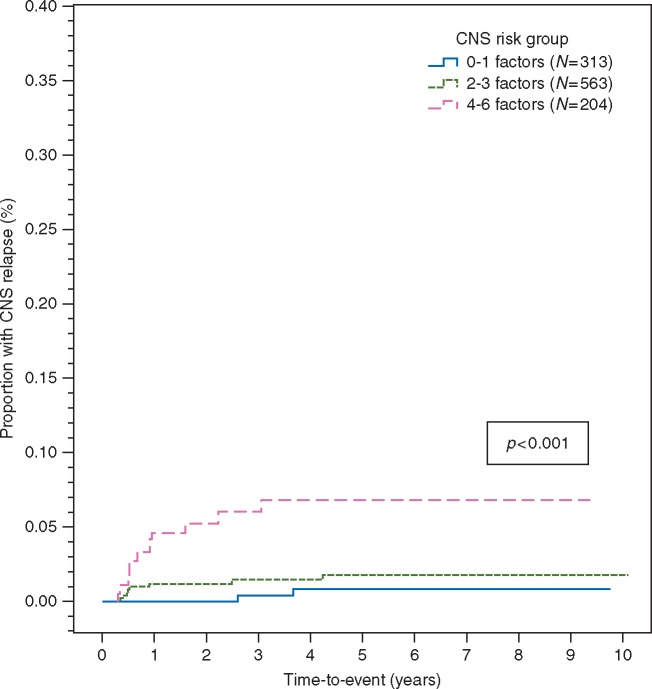

Applying the CNS-IPI patients were categorised as low-risk = 313/1080 (29.0%), intermediate-risk 563/1080 (52.1%) and high-risk = 204/1080 (18.9%) accordingly. The proportion receiving CNS prophylaxis was 15.3%, 14.4% and 31.4% in each group, respectively. The number of CNS relapses by group were: low-risk = 2, intermediate-risk = 8 and high-risk = 11, with a 2-year (0%, 1.2%; 95% CI, 0.2% to 2.2% and 5.2%; 95% CI, 1.9% to 8.5%) and 5-year (0.8%; 95% CI, 0% to 2.0%, 1.7%; 95% CI, 0.5% to 2.9% and 6.8%; 95% CI, 2.9% to 10.7%) incidence of CNS relapse accordingly (Figure 2). Adjusting for CNS-IPI risk group according to use of CNS prophylaxis did not demonstrate a clinical benefit (hazard ratio = 1.12; 95% CI, 0.40–3.14; P = 0.83) (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 2.

Application of the CNS-IPI risk model.

Discussion

At a median follow-up of 6.5 years, the cumulative incidence of CNS relapse of 1.9% following R-CHOP was very low. The majority of relapses involved the brain parenchyma and isolated leptomeningeal involvement was rare. Relapses in the CNS tended to occur earlier than systemic relapse, and most (14/21) occurred within the first year following registration. Consistent with prior studies [1] the prognosis following CNS relapse in our cohort was poor, with a median OS of 3.5 months. One patient with CNS relapse was from the recently reported PMBL subgroup analysis equating to an incidence of 2.0% (1/50) for this cohort, consistent with published reports in the rituximab era [20].

Although several risk factors for CNS relapse were identified on UVA, none remained independently significant in MVA due to the low number of events. None of the biomarkers tested were significant in UVA, but this must be interpreted in the context of low numbers tested. Application of the CNS-IPI identified a high-risk group with 2 and 5-year incidences of CNS relapse of 5.2% and 6.8% respectively, providing further validation for this risk model. The incidence of CNS relapse for patients selected to receive prophylaxis was 2.8% (2.5% for patients who received IT-MTX) which might suggest some efficacy for this therapy; however when we evaluated the CNS-IPI adjusting for prophylaxis use, no benefit could be demonstrated overall, although small numbers in some individual groups limits interpretation. Five patients who developed CNS recurrence (parenchymal n = 4, isolated leptomeningeal n = 1) received IT MTX prophylaxis (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online), highlighting the potential for treatment-failures with this approach.

The strength of our analysis lies in the evaluation of an unselected cohort of DLBCL patients aged ≥18 years who were uniformly R-CHOP-treated within in the setting of a large multicentre prospective clinical trial. The long duration of follow-up is an additional strength given the propensity for late-onset recurrences. However, as a retrospective evaluation of a prospective trial the analysis was not pre-planned and the study was not designed or powered at the outset to evaluate this particular end point. The low number of CNS events also precluded the identification of independent risk factors.

Evaluation of CNS relapse in DLBCL poses several challenges for researchers due to its rarity. Comparison between studies is also inherently difficult due to the heterogeneity of the populations reported in the literature, some of which are selected [4, 6, 10, 12, 13], or include patients with other aggressive B-cell lymphoma histologies as well as DLBCL.[4, 16, 21] Variation in prophylaxis use between cohorts further complicates data interpretation.

The addition of rituximab to CHOP has consistently improved outcomes for patients with previously untreated DLBCL, but the impact on preventing CNS recurrence is more controversial [4–13, 22]. On the whole, consensus opinion supports the view that there has been a reduction in CNS relapse in the rituximab era consequent to improved control of systemic disease [2, 3].

The pattern of CNS relapse in DLBCL also appears to have evolved with rituximab, with relapses increasingly involving the brain parenchyma rather than the leptomeninges [1, 7, 8], the latter being more prevalent previously [1]. A higher proportion of CNS recurrences occurring in isolation are also reported for rituximab-treated patients [4, 6] similarly attributed to improved systemic disease control.

Although we also identified a high-risk CNS-IPI group, overall we observed a lower incidence of CNS relapse across all risk groups than that reported by Schmitz et al. [16] and the distinction between low and intermediate-risk was less clearly defined in our analysis. This may be explained by differences between the cohorts studied, for example patients evaluated by the BCCA were older with a higher proportion of patients with increased PS (>2) and IPI as anticipated with a population-based cohort, in contrast to our trial population where patients with PS >2 were excluded from participation which may have resulted in fewer CNS events. Furthermore the indications for CNS prophylaxis differed between studies, in the DSHNHL trials prophylaxis was mandated for patients with involvement of bone marrow, testes or involvement of lymph nodes of the head and neck in 5/8 of these studies [16], while for the BCCA cohort prophylaxis was administered only to patients with sinus involvement for the main duration of the analysis.

Controversy surrounds CNS prophylaxis given the limited and conflicting evidence-base, potential for associated toxicity, and consequent demand placed on hospital services. In practice IT MTX is the most widely used prophylaxis, and while several studies support this approach [23, 24], not all have demonstrated benefit [4, 11]. Concerns also exist regarding IT administration in terms of preventing parenchymal relapses in particular [2, 6]. As systemic MTX is the mainstay of therapy for primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) and given the reported efficacy as CNS prophylaxis [25] many advocate this mode of administration. In our analysis however only a minority of patients (n = 2) received IV MTX but despite this, the risk of CNS recurrence was extremely low, even in patients deemed to be high-risk at the outset.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate a reduction in CNS relapse rates in the rituximab era. For patients selected to receive prophylaxis, the incidence of CNS relapse was 2.8%, which might suggest some benefit, possibly reflected by a low incidence of leptomeningeal relapse (where the IT route of administration is most likely to exert effect); although an exploratory analysis of CNS-IPI group adjusted for prophylaxis use did not show an overall risk reduction. The low number of CNS events we observed overall also calls into question the additional benefit of using IV MTX in this setting, given the potential for increased toxicity. Ultimately, however, randomised clinical trials will be required to determine the optimal approach in high-risk patients. In the future incorporation of novel agents such as lenalidomide, ibrutinib, and nivolumab, which are currently being evaluated in combination with R-CHOP, may conceivably reduce CNS relapse rates even further in DLBCL given the emerging data on their efficacy in relapsed or refractory PCNSL in the recently reported clinical studies NCT01956695, NCT02542514 and NCT02857426, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank participating centers of the R-CHOP 14 versus 21 trial (ISCRTN 16017947), as well as the patients involved and their families.

Funding

Cancer Research UK provided endorsement and funding of the R-CHOP 14 versus 21 trial (CRUKE/03/019). The National Health Service (NHS) provided funding to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centres at both University College London and the Royal Marsden Hospital/Institute of Cancer Research, London, UK (no grant numbers apply). Chugai Pharmaceuticals provided an educational grant and lenograstim within the R-CHOP14v21 trial.

Disclosure

DC has received research funding from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Celgene, Medimmune, Merrimack, Merck Serono and Sanofi. EAH has received travel expenses from Takeda and Bristol-Myers Squibb. KMA has received research funding, conference expenses and honoraria for attending or chairing advisory boards from Roche. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Kridel R, Dietrich PY.. Prevention of CNS relapse in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12(13): 1258–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McMillan A, Ardeshna KM, Cwynarski K. et al. Guideline on the prevention of secondary central nervous system lymphoma: British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol 2013; 163(2): 168–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang J, Chen B, Xu X.. Impact of rituximab on incidence of and risk factors for central nervous system relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leuk. Lymphoma 2014; 55(3): 509–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boehme V, Schmitz N, Zeynalova S. et al. CNS events in elderly patients with aggressive lymphoma treated with modern chemotherapy (CHOP-14) with or without rituximab: an analysis of patients treated in the RICOVER-60 trial of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Blood 2009; 113(17): 3896–3902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shimazu Y, Notohara K, Ueda Y.. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with central nervous system relapse: prognosis and risk factors according to retrospective analysis from a single-center experience. Int J Hematol 2009; 89(5): 577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Villa D, Connors JM, Shenkier TN. et al. Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the impact of the addition of rituximab to CHOP chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2009; 21(5): 1046–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guirguis HR, Cheung MC, Mahrous M. et al. Impact of central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis on the incidence and risk factors for CNS relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era: a single centre experience and review of the literature. Br J Haematol 2012; 159(1): 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mitrovic Z, Bast M, Bierman PJ. et al. The addition of rituximab reduces the incidence of secondary central nervous system involvement in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2012; 157(3): 401–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumar A, Vanderplas A, LaCasce AS. et al. Lack of benefit of central nervous system prophylaxis for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era: findings from a large national database. Cancer 2012; 118(11): 2944–2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feugier P, Virion JM, Tilly H. et al. Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system occurrence in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: influence of rituximab. Ann. Oncol 2004; 15(1): 129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tai WM, Chung J, Tang PL. et al. Central nervous system (CNS) relapse in diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL): pre- and post-rituximab. Ann. Hematol 2011; 90(7): 809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yamamoto W, Tomita N, Watanabe R. et al. Central nervous system involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Haematol 2010; 85(1): 6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tomita N, Yokoyama M, Yamamoto W. et al. Central nervous system event in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. Cancer Sci 2012; 103(2): 245–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Savage KJ, Slack GW, Mottok A. et al. Impact of dual expression of MYC and BCL2 by immunohistochemistry on the risk of CNS relapse in DLBCL. Blood 2016; 127(18): 2182–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fletcher C, Kahl B.. Central nervous system involvement in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: an analysis of risks and prevention strategies in the post-rituximab era. Leuk. Lymphoma 2014; 55(10): 2228–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Nickelsen M. et al. CNS international prognostic index : a risk model for CNS relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(26): 3150–3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cunningham D, Hawkes EA, Jack A. et al. Rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone in patients with newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a phase 3 comparison of dose intensification with 14-day versus 21-day cycles. Lancet 2013; 381(9880): 1817–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gleeson M, Hawkes EA, Cunningham D. et al. Rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisolone (R-CHOP) in the management of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: a subgroup analysis of the UK NCRI R-CHOP 14 versus 21 trial. Br J Haematol 2016; 175(4): 668–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC. et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004; 103(1): 275–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Papageorgiou S, Diamantopoulos P, Levidou G. et al. Isolated central nervous system relapses in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma after CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab. Hematol Oncol 2013; 31(1): 10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boehme V, Zeynalova S, Kloess M. et al. Incidence and risk factors of central nervous system recurrence in aggressive lymphoma - A survey of 1693 patients treated in protocols of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Ann Oncol 2007; 18(1): 149–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Glass B. et al. CNS disease in younger patients with aggressive B-cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients treated on the Mabthera International Trial and trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group. Ann Oncol 2012; 23(5): 1267–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomita N, Kodama F, Kanamori H. et al. Prophylactic intrathecal methotrexate and hydrocortisone reduces central nervous system recurrence and improves survival in aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer 2002; 95(3): 576–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arkenau H-T, Chong G, Cunningham D. et al. The role of intrathecal chemotherapy prophylaxis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2007; 18(3): 541–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abramson JS, Hellmann M, Barnes JA. et al. Intravenous methotrexate as central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis is associated with a low risk of CNS recurrence in high-risk patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer 2010; 116(18): 4283–4290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.