Abstract

Background

The purpose of our study was to characterize the causes of death among cancer patients as a function of objectives: (i) calendar year, (ii) patient age, and (iii) time after diagnosis.

Patients and methods

US death certificate data in Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Stat 8.2.1 were used to categorize cancer patient death as being due to index-cancer, nonindex-cancer, and noncancer cause from 1973 to 2012. In addition, data were characterized with standardized mortality ratios (SMRs), which provide the relative risk of death compared with all persons.

Results

The greatest relative decrease in index-cancer death (generally from > 60% to < 30%) was among those with cancers of the testis, kidney, bladder, endometrium, breast, cervix, prostate, ovary, anus, colorectum, melanoma, and lymphoma. Index-cancer deaths were stable (typically >40%) among patients with cancers of the liver, pancreas, esophagus, and lung, and brain. Noncancer causes of death were highest in patients with cancers of the colorectum, bladder, kidney, endometrium, breast, prostate, testis; >40% of deaths from heart disease. The highest SMRs were from nonbacterial infections, particularly among <50-year olds (e.g. SMR >1,000 for lymphomas, P < 0.001). The highest SMRs were typically within the first year after cancer diagnosis (SMRs 10–10,000, P < 0.001). Prostate cancer patients had increasing SMRs from Alzheimer's disease, as did testicular patients from suicide.

Conclusion

The risk of death from index- and nonindex-cancers varies widely among primary sites. Risk of noncancer deaths now surpasses that of cancer deaths, particularly for young patients in the year after diagnosis.

Keywords: cancer, comorbidity, heart disease, mortality, SEER, second cancer, United States, non-cancer death, competing events, clinical trials, epidemiology

Introduction

Cancer accounts for a significant portion of deaths around the world [1] and in the United States (US) [2–4]. Worldwide, in 2013, cancer killed over 8 million; it has moved from the third leading cause of death in 1990 to the second leading cause of death in 2013, following heart disease [3]. In the United States, during 2013, heart disease was responsible for 611 105 deaths, followed by cancer at 584 881 [4]. Substantial progress has been made since the 1990s in the United States [5] and in Europe [6] with regard to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of various cancers. As survivorship from cancer continues to increase [7], the principal participants of the healthcare field (e.g. patients, providers, and payers) should identify the cancer patients at highest risk of dying, as well as their risk of a particular cause of death.

KEY MESSAGE

Patients with cancer of the lung, pancreas, and brain are most likely to die of their cancer. Second cancers are important causes of death for cancers of hematologic system, oropharynx, testis, larynx. Patients with breast and prostate cancer are at highest risk of non-cancer death. Relative risk of death is highest in first year after diagnosis, particularly for young patients.

The purposes of this work are to characterize the causes of death among cancer patients in the United States as a function of (i) calendar year, (ii) patient age, and (iii) time after diagnosis. The results identify the patients who (i) are at lowest risk to die of their cancer; (ii) are at highest risk to die of their cancer; (iii) might profit from intense screening for second cancers; and (iv) are at highest risk of noncancer death (and its causes). Additionally, these findings may identify areas of oncology that would most benefit from further research.

Methods

The analytical strategy can be broken into three components (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Patients developing invasive cancer, diagnosed between 1973 and 2012, were abstracted from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program [8, 9]. The complete methods and limitations for each objective are described in supplementary Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online. SEER is a network of population-based incident tumor registries from geographically distinct regions in the United States, covering 28% of the US population, including incidence, survival, and treatment (e.g. radiation therapy, surgery, and chemotherapy) [8, 9]. The SEER registry does not code comorbidities, performance status, surgical pathology, margin status, doses, or agents. SEER*Stat 8.2.1 was used for analysis [8]. Patients diagnosed only through autopsy or death certificate were excluded.

The strategy for objective I is shown in supplementary Figure S2 and Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Death, based on death certificate, was coded as being as due to “index-cancer,” (i.e. the cancer originally diagnosed in the patient), “nonindex-cancer” (i.e. a second primary), and “noncancer death” (i.e. death from any medical cause not coded as cancer). To account for discrepancies, for certain sites, deaths attributed to locoregional cancer subsites were included as part of the index-cancer death (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

For objectives II and III, the analysis of death was undertaken according to published methods for suicide [10] including a total of 26 noncancer causes of deaths; the top 13 causes of death were reported, using standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) [8]. SMRs provide the relative risk of death for patients with cancer as compared with all US residents [10, 11]. Data were characterized with SMRs adjusted by age, race, and sex to the US population over the same time. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the SMRs were calculated using SEER*Stat 8.2.1 and Microsoft Excel 15.0.4 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) [11–13]. At least 1000 person-years at risk were necessary for each cause of death with respect to cancer type to minimize the CIs (CIs are listed in supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Results

Deaths per calendar year

Index-cancer deaths

Death rates are illustrated in Figure 1; individual yearly rates of death are provided in supplementary Figure S1 and Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. The greatest decrease in index-cancer death (generally from >60% to <30% of patients) was noted (black lines with negative slope in Figure 1) among those with cancers of the testis, kidney, bladder, endometrium, breast, cervix, prostate, ovary, anus, colorectum, melanoma, and lymphomas. The high proportions of death due to cancer in the early years of SEER reflect the low risk of death due to causes other than cancer. Notably, patients diagnosed in recent years with cancers that have an indolent course are not represented among these curves because these patients have not yet died of any cause. The majority of deaths among cancer patients in recent years are not due to the index-cancer (Figure 2A). Among all cancer patients dying from the index-cancer (Figure 2B), the most had lung tumors. Index-cancer deaths (all typically > 40%) have been relatively stable among patients with cancers of the liver, pancreas, lung and bronchus, esophagus, brain, and multiple myeloma (MM) (Figure 1, black lines with near-zero slope).

Figure 1.

Plots of patient death versus attained calendar year (from 1973 to 2012), for various cancers. Death was characterized as due to “index-cancer,” (black lines; i.e. the cancer originally diagnosed in the patient), “nonindex-cancer” (gray lines; i.e. a second cancer diagnosed in the patient, and not a metastasis from the original cancer), and “noncancer death” (green lines; i.e. death from any medical cause that does not include cancer). Attained calendar year refers to the year in which the death occurred, among all cancers diagnosed since 1973. Cancers subsites are organized by color: light tan = head and neck, skin; genitourinary = yellow; male specific = light blue; female specific = pink; gastrointestinal = dark tan; gray = hematologic.

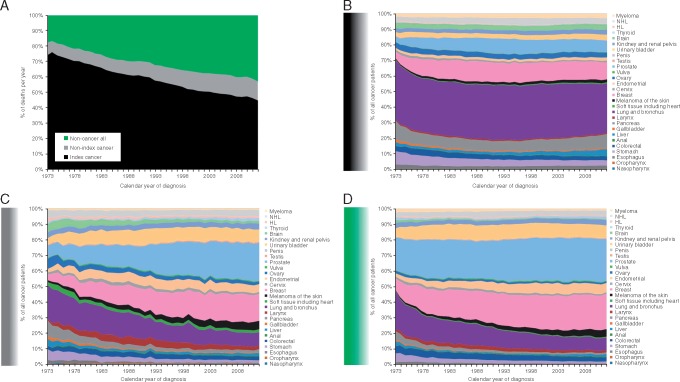

Figure 2.

(A) A plot of death of the proportion of all cancer patients experiencing death due to index-cancer (black), nonindex-cancer (gray), and noncancer cause (gray) among all patients, illustrates that noncancer causes of death have increased while index-cancer causes of death have decreased since the 1970s. Plots of death due to index-cancer (B), nonindex-cancer (C), and noncancer cause (D), among all patients experiencing a death of that cause, stratified by various cancers.

Nonindex-cancer deaths

Currently, the highest incidence of nonindex-cancer death is among patients with the original/first cancer of the oropharynx, testis, soft tissue, larynx, stomach, and lymphoma (gray lines among graphs in Figure 1; all 20%–30%). Over the entire calendar year session, the greatest increase in nonindex-cancer death (i.e. greatest positive slope among gray lines in Figure 1) has been realized among patients with cancers of the gallbladder, prostate, testis, stomach, and Hodgkin's lymphoma (HL). Prostate and breast cancer patients currently experience that highest rate of death due to nonindex-cancers (Figure 2C).

Noncancer deaths

Noncancer causes of death (green lines in Figure 1) are currently highest (versus index- or nonindex-cancer) in patients with cancers of the colorectum, genitourinary tract (e.g. bladder and kidney), female cancers (e.g. endometrial, cervix, breast, and vulvar), male cancers (e.g. prostate, testicular, and penile), tonsil cancer, melanoma of the skin, and lymphomas. For many of these patients, the risk of dying from a different medical condition has superseded the risk of death from any form of cancer.

The most common cause of noncancer death is generally heart disease (red lines among graphs in Figure 1). The highest rates of heart disease-associated death (all 13%–21%) are currently observed among patients with cancers of the prostate, breast, testis, endometrium, larynx, and HL. The primary sites contributing the largest share of noncancer deaths at the inception of the SEER registry, when incidence and prevalence were equivalent, were lung cancer and prostate cancer. The current data, however, show prostate and breast cancer patients contributing the largest share to the overall noncancer mortality rates (Figure 2D).

Noncancer death SMRs

Per-patient age group

For objectives II and III, there were 651 287 deaths due to noncancer causes; the plurality of deaths (279 039) were due to heart disease. The rate of noncancer death varied perpatient age group (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online): those <45 years of age tended to die of “other causes” and “other” infections; older patients died largely of heart disease and “other causes.”

SMRs for the leading causes of noncancer death were characterized after diagnosis, binned by age groups (Figure 3; supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online); a heat map table was created among the most common cancers (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Among all SMR plots, SMRs were highest for younger patients, and (although elevated) they typically decreased—almost all P < 0.05. The highest relative increase in SMRs (for the average of all cancers) was noted for nonbacterial infections, parasites, and human immunodeficiency virus infection; and pneumonia and influenza. The cancers with high SMRs tended to be of immunologic/hematologic origin: leukemias, lymphomas, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and MM. Additionally, lung and bronchus cancer consistently displayed increased SMRs.

Figure 3.

SMRs for the leading causes of noncancer death were characterized after diagnosis, binned by patient age. An SMR above 1 represents a higher relative risk of death for a particular cause, when compared with the noncancer population. Black lines represent SMRs from all sites; purple from lung and bronchus cancer; blue from prostate cancer; pink from breast cancer; and brown from colorectum. Select cancers with outlier SMRs (green, red, and yellow lines) are also plotted.

During follow-up

When noncancer deaths were plotted versus time after diagnosis (Figure 4;supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online), heart disease was the leading cause (∼40% of deaths) for patients at all time points. SMRs for the leading causes of noncancer death were characterized as a function of time after diagnosis (supplementary Figure S6, available at Annals of Oncology online); a heat map table was created among the most common cancers (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). Lung cancer patients were most likely to die of medical comorbidities, compared with patients with any other type of cancer. Among all SMR plots, the highest relative increase in SMRs (for the average of all cancers) was attributable to nonbacterial infections, parasites, and human immunodeficiency virus infection. Among the patients dying from suicide and self-inflicted injury, those with lung and bronchus cancer had the highest SMR within the first year, followed by breast cancer and testis cancer. Testis cancer patients, however, had the highest persistent risk of suicide and self-inflicted injury.

Figure 4.

SMRs for the leading causes of noncancer death were characterized after diagnosis, binned by time periods. An SMR above 1 represents a higher relative risk of death for a particular cause, when compared with the noncancer population. Black lines represent SMRs from all sites; purple from lung and bronchus cancer; blue from prostate cancer; pink from breast cancer; and brown from colorectum. Select cancers with outlier SMRs (green, red, and yellow lines) are also plotted.

Discussion

Previous analyses have reported on the causes of death among patients with individual cancers (e.g. prostate [14] and breast [15]), or among various cancer patients dying of a particular cause of death (e.g. suicide [10]). The current study is unique in that it characterizes causes of death among 28 individual cancers, from 13 causes of death, as a function of calendar year, follow-up time, and patient age. Thus, the current work is synergistic and the largest of its kind. We report that patients with prostate, breast, and testis cancer are least likely to die of their cancer. Patients with lung, pancreas, and brain tumors are most likely to die of their cancer. Patients with cancer of the oropharynx, larynx, and HL may benefit from screening or early detection of second cancers. Patients with prostate and breast cancer are at highest risk to die of noncancer death. Noncancer death is most likely due to heart disease, either from treatment or from general risk factors; or infection, likely secondary to treatment.

The analysis helps to identify the patients who are least likely to die of their cancer (e.g. those with cancer of the larynx, stomach, bladder, endometrium, breast, testis, prostate, anus, colorectum, ovary, and melanoma, NHL, and HL). Although the death rate from prostate and breast cancer has declined, the absolute number of patients dying to these diseases remains elevated because of the high incidence of the cancers (Figure 2A). The observed benefits in index-cancer death rates may come from screening (e.g. prostate-specific antigen [16] or mammography [17]). Some cancers included in this analysis may be presenting at an earlier stage, when they are curable, increasing the denominator and decreasing the percentage of patients dying of the index-cancer. Benefits in the treatment may also be due to improvements in surgical, radiation, and medical oncology. Most have been incremental, but some have been dramatic [18].

The study identifies diseases demanding more effective therapies, prevention, and early detection [19]. They may benefit from increased research funding [20]. These sites include cancers of the liver, pancreas, lung and bronchus, nasopharynx, esophagus, brain, and MM (Figure 1).

Patients who might benefit from screening and more effective treatment of second cancers (Figure 1, gray lines with positive slopes; Figure 2C), include those with cancers of the prostate, breast, lung, colorectum, oropharynx, testis, larynx, and HL. There may be a need for effective surveillance of patients after curative treatment of these cancers [21–23]. Some of these cancers present in the young (e.g. HL and testis); subsequent cancers may be referable to treatment (e.g. breast cancer development after RT for HL) [23]. Patients with larynx, oropharynx, and bladder tumors probably developed second cancers because of tobacco exposure [24], emphasizing the need for complete cessation. Among other cancers (e.g. ovarian and breast), the risk of a subsequent malignancy may be attributable to another cancer is likely secondary to genetic factors [25]. Indeed, second cancers may simply reflect diseases arising in any aging population.

Those at highest risk of noncancer death may largely be divided into two groups: (i) those with chronic comorbid conditions and (ii) acute, iatrogenic, or treatment-induced infections. The most common chronic comorbid conditions are secondary to cardiovascular disease, including heart disease and cerebrovascular diseases. For older patients with common cancers (e.g. breast, prostate, colorectal; per supplementary Tables S1 and S2 and Figures S3 and S4, available at Annals of Oncology online), measures to maintain general health are appropriate. Site-specific survivorship guidelines have been published for many malignancies [21, 23, 26, 27] .

The risk of death from a particular cause varies with follow-up time (supplementary Tables S2 and S3 and Figures S5 and S6, available at Annals of Oncology online). The SMR of suicide increases (versus SMRs of other causes of death), likely because of a high incidence of depression among these patients [28]. These results concur with the findings of a SEER analysis that noted higher suicide rates in cancer survivors [10]. The SMR of Alzheimer’s disease rises rapidly in prostate cancer patients, compared with all others, corroborating the work of Nead et al [29].

One cohort of patients likely to die of noncancer causes is younger patients with hematologic malignancy (e.g. leukemias, lymphomas; per supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). These deaths frequently occur within the first year after cancer diagnosis and probably result from treatment. As cure rates for childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers (e.g. lymphomas and leukemias) have improved, treatment-related deaths now account for a high percentage of all deaths [30–32].

This analysis has important limitations. Death due to the index-cancer may be miscoded; typically, the errors in coding are referable to attributing a locoregional relapse to a new cancer or metastasis to an adjacent organ [8, 9]. We arbitrarily grouped deaths from such causes together and are unable to assess the true incidence of such nonindex-cancers (supplementary Figures S1 and S2 and Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). Some noncancer causes of death may actually be referable to treatment; we attempted to identify them using patient age and time after diagnosis. In addition, “other causes” of death or “other” infections counted among noncancer causes of death are likely due to treatment-related infections. Finally, patients in the SEER database are accrued over time beginning in 1973; thus, patients appear to have a higher risk of death because the number of all cancer patients in the database is smaller and yield a smaller denominator. Additionally, patients diagnosed in earlier years have longer follow-up and more time at risk than patients diagnosed more recently. Similarly, patients diagnosed in recent years have short follow-up and lower chance of death from any cause. A competing risk analysis was not carried out, as this was not the purpose of the current study. We included all patients in the SEER registry to reduce the risk of additional bias in selecting patients with a minimum follow up.

Conclusions

The risk of death from index- and nonindex-cancers varies widely among primary sites. Risk of specific noncancer deaths is substantial, particularly in the year after diagnosis. Patients with cancer of the lung, pancreas, and brain are most likely to die of their cancer. These sites may benefit from additional research funding. Second cancers are important causes of death for patients with cancers of the oropharynx, testis, larynx, and HL; these patients may benefit from more effective surveillance. Patients with breast and prostate cancer are at highest risk of noncancer death. Heart disease, whether from treatment or age, is an important cause of death, as is infection (probably due to treatment).

Funding

This publication was supported by grant number P30 CA006927 from the National Cancer Institute, NIH. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure

All authors have read and approved the article. We have no financial disclosures. We are not using any copyrighted information, patient photographs, identifiers, or other protected health information in this paper. No text, text boxes, figures, or tables in this article have been previously published or owned by another party. We have no conflicts of interests.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65: 87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A.. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2014; 64: 9–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mortality GBD. Causes of Death C. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 385: 117–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. National Vital Statistics Report (NVSR). Deaths: Final Data for 2013. In. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Census Bureau 2013.

- 5. Edwards BK, Noone AM, Mariotto AB. et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2010, featuring prevalence of comorbidity and impact on survival among persons with lung, colorectal, breast, or prostate cancer. Cancer 2014; 120: 1290–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coleman MP, Gatta G, Verdecchia A. et al. EUROCARE-3 summary: cancer survival in Europe at the end of the 20th century. Ann Oncol 2003; 14 (Suppl 5): v128–v149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Masters GA, Krilov L, Bailey HH. et al. Clinical cancer advances 2015: Annual report on progress against cancer from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 786–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software version 8.2.1. In 2016.

- 9. Warren JL, Klabunde CN, Schrag D. et al. Overview of the SEER-Medicare data: content, research applications, and generalizability to the United States elderly population. Med Care 2002; 40: IV–I3. 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Misono S, Weiss NS, Fann JR. et al. Incidence of suicide in persons with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4731–4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koepsell TD, Weiss NS, Epidemiologic Methods: Studying the Occurrence of Illness. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Breslow NE, Day NE, Statistical methods in cancer research: Volume II—The design and analysis of cohort studies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ury HK, Wiggins AD.. Another shortcut method for calculating the confidence interval of a Poisson variable (or of a standardized mortality ratio). Am J Epidemiol 1985; 122: 197–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Newschaffer CJ, Otani K, McDonald MK, Penberthy LT.. Causes of death in elderly prostate cancer patients and in a comparison nonprostate cancer cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92: 613–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Colzani E, Liljegren A, Johansson AL. et al. Prognosis of patients with breast cancer: causes of death and effects of time since diagnosis, age, and tumor characteristics. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 4014–4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Attard G, Parker C, Eeles RA. et al. Prostate cancer. Lancet 2016; 387(10013): 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Myers ER, Moorman P, Gierisch JM. et al. Benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: a systematic review. JAMA 2015; 314: 1615–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meyts ER, McGlynn KA, Okamoto K. et al. Testicular germ cell tumours. Lancet 2015; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wada K, Takaori K, Traverso LW.. Screening for pancreatic cancer. Surg Clin North Am 2015; 95: 1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. American Cancer Society: Current Grants by Cancer Type. In 2015. https://www.cancer.org/research/currently-funded-cancer-research/grants -by-cancer-type.html.

- 21. Steele SR, Chang GJ, Hendren S. et al. Practice Guideline for the surveillance of patients after curative treatment of colon and rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2015; 58: 713–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goodwin PJ, Ambrosone CB, Hong CC.. Modifiable lifestyle factors and breast cancer outcomes: current controversies and research recommendations. Adv Exp Med Biol 2015; 862: 177–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ng AK. Current survivorship recommendations for patients with Hodgkin lymphoma: focus on late effects. Blood 2014; 124: 3373–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shiels MS, Gibson T, Sampson J. et al. Cigarette smoking prior to first cancer and risk of second smoking-associated cancers among survivors of bladder, kidney, head and neck, and stage I lung cancers. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 3989–3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bouchardy C, Benhamou S, Fioretta G. et al. Risk of second breast cancer according to estrogen receptor status and family history. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 127: 233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morgan MA, Denlinger CS.. Survivorship: tools for transitioning patients with cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2014; 12: 1681–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Denlinger CS, Ligibel JA, Are M. et al. Survivorship: healthy lifestyles, version 2.2014. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2014; 12: 1222–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chochinov HM. Depression in cancer patients. Lancet Oncol 2001; 2: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nead KT, Gaskin G, Chester C. et al. Androgen deprivation therapy and future Alzheimer's disease risk. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(6): 566–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hunger SP, Mullighan CG.. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1541–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lyman GH, Morrison VA, Dale DC. et al. Risk of febrile neutropenia among patients with intermediate-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma receiving CHOP chemotherapy. Leuk Lymphoma 2003; 44: 2069–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J. et al. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer 2006; 106: 2258–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.