Abstract

Background

Previous analysis of COMBI-d (NCT01584648) demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) with combination dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib monotherapy in BRAF V600E/K-mutant metastatic melanoma. This study was continued to assess 3-year landmark efficacy and safety after ≥36-month follow-up for all living patients.

Patients and methods

This double-blind, phase 3 study enrolled previously untreated patients with BRAF V600E/K-mutant unresectable stage IIIC or stage IV melanoma. Patients were randomized to receive dabrafenib (150 mg twice daily) plus trametinib (2 mg once daily) or dabrafenib plus placebo. The primary endpoint was PFS; secondary endpoints were OS, overall response, duration of response, safety, and pharmacokinetics.

Results

Between 4 May and 30 November 2012, a total of 423 of 947 screened patients were randomly assigned to receive dabrafenib plus trametinib (n = 211) or dabrafenib monotherapy (n = 212). At data cut-off (15 February 2016), outcomes remained superior with the combination: 3-year PFS was 22% with dabrafenib plus trametinib versus 12% with monotherapy, and 3-year OS was 44% versus 32%, respectively. Twenty-five patients receiving monotherapy crossed over to combination therapy, with continued follow-up under the monotherapy arm (per intent-to-treat principle). Of combination-arm patients alive at 3 years, 58% remained on dabrafenib plus trametinib. Three-year OS with the combination reached 62% in the most favourable subgroup (normal lactate dehydrogenase and <3 organ sites with metastasis) versus only 25% in the unfavourable subgroup (elevated lactate dehydrogenase). The dabrafenib plus trametinib safety profile was consistent with previous clinical trial observations, and no new safety signals were detected with long-term use.

Conclusions

These data demonstrate that durable (≥3 years) survival is achievable with dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAF V600-mutant metastatic melanoma and support long-term first-line use of the combination in this setting.

Keywords: melanoma, metastatic, BRAF, dabrafenib, trametinib, durable outcomes

Introduction

Before recent therapeutic advances, the prognosis for patients with metastatic melanoma was poor, with a 5-year survival of ∼6% and a median overall survival (OS) of 7.5 months [1]. The anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (anti-CTLA-4) therapy ipilimumab was the first agent to show durable clinical benefit lasting ≥5 years in a subset of patients within molecularly unselected advanced melanoma populations [2]. More recently, BRAF and MEK inhibitor (BRAFi/MEKi) combinations and anti-programmed death-1 (anti-PD-1) checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapy regimens demonstrated significant improvements in clinical outcomes in phase 3 trials of patients with metastatic melanoma; however, extended follow-up in these studies has been limited to ≤2 years [3–9]. Targeted therapies have been purported to be associated with rapid deterioration and death following development of secondary resistance; however, evidence from long-term, large randomized studies is lacking. With multiple treatments now available for BRAF V600-mutant melanoma, a better understanding of the proportion and characteristics of patients who can derive durable benefit and maintain tolerability with long-term use of current therapies is needed for optimizing treatment.

Combination dabrafenib and trametinib (D + T) demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) and OS over BRAFi monotherapy in randomized phase 2 and 3 trials in patients with BRAF V600E/K-mutant stage IIIC unresectable or stage IV metastatic melanoma [3, 4, 10–13]. The D + T safety profile has been consistent across these studies, in which the combination has been associated with a reduction in hyperproliferative skin lesions [e.g. squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), keratoacanthoma (KA)] compared with BRAFi monotherapy, while the frequency and severity of pyrexia appear higher [3, 4, 10].

In the most recent analysis of COMBI-d, a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial of D + T versus dabrafenib monotherapy (dabrafenib plus placebo), with a median follow-up of 20.0 months for the D + T arm and 16.0 months for the monotherapy arm, median PFS was 11.0 versus 8.8 months [HR, 0.67; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.53–0.84; P = 0.0004], median OS was 25.1 versus 18.7 months (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55–0.92; P = 0.0107), and 2-year OS was 51% versus 42% [3]. These findings confirmed results from the primary analysis of COMBI-d [12] and were consistent with outcomes observed in the randomized phase 3 COMBI-v study of D + T versus vemurafenib [4]. The longest follow-up to date for D + T in a randomized study (median 45.6 months) was reported for the phase 2 BRF113220 study (part C) evaluating D + T (n = 54) versus dabrafenib monotherapy (n = 54) [11], in which D + T-treated patients had a 2- and 3-year PFS of 25% and 21%, respectively, and a 2- and 3-year OS of 51% and 38%, respectively. Pooled data across these trials (median follow-up of 20.0 months) showed that normal baseline serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and <3 organ sites containing metastasis were the factors most predictive of durable outcomes; patients with both of these characteristics had a 2-year PFS of 46% and a 2-year OS of 75% [14].

Here, we report an updated 3-year landmark analysis for the phase 3 COMBI-d trial, including updated PFS, OS, best response and safety analyses.

Methods

The COMBI-d study (protocol previously published [3] and further described in the supplementary data, available at Annals of Oncology online) was continued after prior primary and OS analyses [3, 12] to provide an updated 3-year landmark analysis of long-term outcomes. Crossover was permitted following the previous OS analysis by patient/physician discretion on the intent-to-treat principle, by which any crossover benefit was applied to the randomized therapy arm estimates. Kaplan–Meier estimations of 2- and 3-year PFS and OS were carried out to describe long-term outcomes. Influences of prognostic factors on patient-derived benefit were explored with descriptive subgroup stratification by baseline factors previously identified as being predictive of outcomes in patients receiving D + T [14].

Results

Baseline characteristics were well balanced across 423 patients randomly assigned to receive D + T (n = 211) or dabrafenib monotherapy (n = 212; supplementary Figure S1 and Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). At data cut-off, 15 February 2016, patients who were alive had ≥36 months of follow-up from time of randomization. Forty (19%) D + T-arm patients versus 6 (3%) monotherapy-arm patients remained on randomized treatment.

At data cut-off, 3-year PFS was 22% for the D + T arm and 12% for the monotherapy arm [HR, 0.71 (95% CI, 0.57–0.88)] (Figure 1A), and 3-year OS was 44% and 32%, respectively [HR, 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58–0.96)] (Figure 2A). Notably, 25 (12%) patients in the dabrafenib monotherapy arm crossed over to D + T, of which 6 (24%) had progressed on monotherapy before crossover. Survival outcomes in these crossover patients, all of whom remained on D + T as of data cut-off, continued to be followed up under the monotherapy arm. Of combination-arm patients who were progression free (n = 31) and alive (n = 76) at 3 years, 28 (90%) and 44 (58%) remained on D + T, respectively.

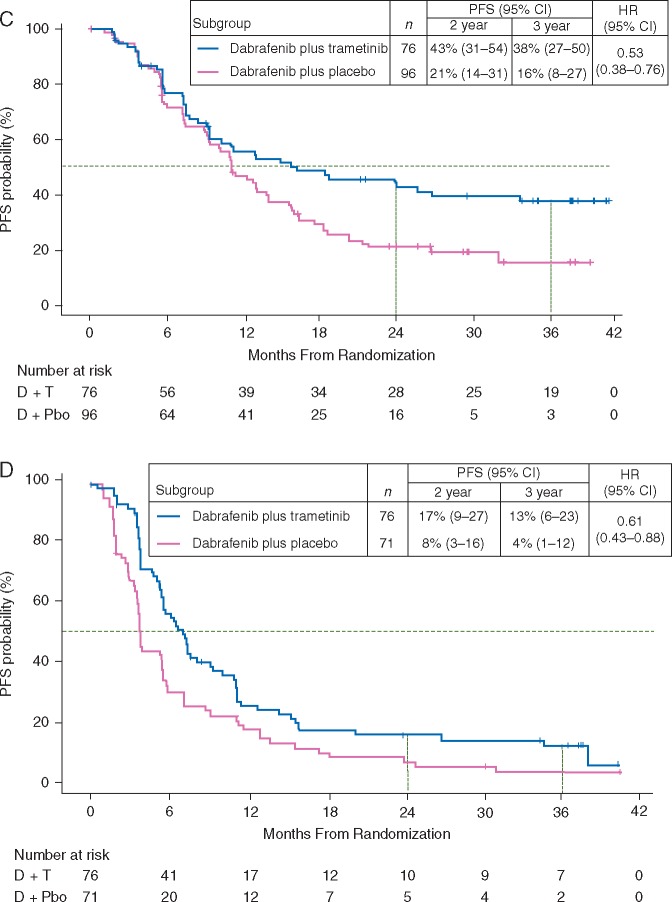

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival (PFS) in the dabrafenib and trametinib (D + T) and dabrafenib monotherapy [D + placebo (Pbo)] arms in (A) the intent-to-treat population and patients with (B) normal baseline lactate dehydrogenase (≤upper limit of normal), (C) normal baseline lactate dehydrogenase and <3 organ sites with metastasis, and (D) elevated baseline lactate dehydrogenase (>upper limit of normal). CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. aIncludes 25 patients who crossed over from monotherapy to the combination. bOf D + T patients who were progression free at 3 years, 28 (90%) remained on D + T.

Figure 2.

Overall survival (OS) in the dabrafenib and trametinib (D + T) and dabrafenib monotherapy [D + placebo (Pbo)] arms in (A) the intent-to-treat population and patients with (B) normal baseline lactate dehydrogenase (≤upper limit of normal), (C) normal baseline lactate dehydrogenase and <3 organ sites with metastasis, and (D) elevated baseline lactate dehydrogenase (>upper limit of normal). CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. aIncludes 25 patients who crossed over from monotherapy to the combination. bOf patients in the D + T arm alive at 3 years, 44 (58%) remained on D + T.

As expected per the progression rate in each arm, more monotherapy-arm patients received post-progression systemic therapy versus D + T-arm patients [130/211 (62%) versus 101/209 (48%); supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online]. In both the D + T and monotherapy groups, immunotherapy was the most common subsequent anticancer therapy (56% versus 56%, respectively); ipilimumab was the most common immunotherapy (41% versus 50%), with fewer patients receiving nivolumab (7% versus 5%) or pembrolizumab (13% versus 11%).

Long-term PFS and OS consistently favoured D + T over monotherapy, regardless of baseline prognostic factors. Three-year PFS rates in patients with normal baseline LDH levels [≤upper limit of normal (ULN), n = 273/423 (65%)] were 27% in the D + T arm versus 17% in the monotherapy arm [HR, 0.70 (95% CI, 0.53–0.93)] (Figure 1B), and 3-year OS rates were 54% versus 41%, respectively [HR, 0.74 (95% CI, 0.53–1.03)] (Figure 2B). Of 133 D + T-arm patients with LDH ≤ ULN, 61 (46%) were alive at 3 years and 34 (26%) remained on D + T. The greatest clinical benefit with D + T was observed in patients with LDH ≤ ULN and <3 organ sites with metastasis at baseline [n = 172/423 (41%)], with 3-year PFS rates of 38% in the combination arm versus 16% in the monotherapy arm [HR, 0.53 (95% CI, 0.38–0.76)] (Figure 1C), and 3-year OS rates of 62% versus 45%, respectively [HR, 0.63 (95% CI, 0.41–0.99)] (Figure 2C). Of 76 combination-arm patients with baseline LDH ≤ ULN and <3 organ sites with metastasis, 37 (49%) were alive at 3 years and 23 (30%) remained on D + T. In patients with baseline LDH > ULN [n = 147/423 (35%)], 3-year PFS rates were 13% in the D + T arm and 4% in the monotherapy arm [HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.43–0.88)] (Figure 1D), and 3-year OS rates were 25% versus 14% [HR, 0.61 (95% CI, 0.41–0.89)] (Figure 2D). Of 76 D + T-arm patients with LDH > ULN, 15 (20%) were alive at 3 years and 10 (13%) remained on D + T.

The confirmed response rates per Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) were 68% in combination-arm patients versus 55% in monotherapy patients (Table 1), with a complete response (CR) rate of 18% versus 15%, respectively. Median duration of response was 12.0 (95% CI, 9.3–17.1) versus 10.6 (95% CI, 8.3–12.9) months.

Table 1.

Confirmed RECIST response

| Dabrafenib plus trametinib | Dabrafenib plus placebo | |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 211) | (n = 212) | |

| RECIST response, n (%) | ||

| Complete response (CR) | 38 (18) | 31 (15) |

| Partial response (PR) | 106 (50) | 85 (40) |

| Stable disease | 51 (24) | 68 (32) |

| Progressive disease | 12 (6) | 18 (8) |

| Not evaluable | 4 (2) | 10 (5) |

| Response rate (CR + PR), n (%) [95% CI] | 144 (68) | 116 (55) |

| [61.5–74.5] | [47.8–61.5] | |

| Duration of response | n = 144 | n = 116 |

| Progressed or died, n (%) | 100 (69) | 84 (72) |

| Median (95% CI), months | 12.0 (9.3–17.1) | 10.6 (8.3–12.9) |

CI, confidence interval; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors.

With a median time on treatment of 11.8 (range, 0.4–43.7) versus 8.3 (range, 0.1–45.3) months in D + T-arm and monotherapy-arm patients, respectively, 49% versus 38% had >12 months of study treatment. Adverse events (AEs) of any grade, regardless of study drug relationship, were observed in 97% of patients (both arms), with 48% of D + T-arm patients versus 50% of monotherapy patients experiencing ≥1 grade 3/4 AE (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online) and 45% versus 38% experiencing serious AEs (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). The incidence of several AEs was higher (>10% difference, any grade) in the D + T versus monotherapy arm: pyrexia (59% versus 33%), chills (32% versus 17%), diarrhoea (31% versus 17%), vomiting (26% versus 15%), and peripheral oedema (22% vs 9%) (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Conversely, the incidence of hyperkeratosis (35% versus 7%), alopecia (28% versus 9%), and skin papilloma (22% versus 2%) was higher in monotherapy-arm versus combination-arm patients (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis (18% versus 5%), SCC/KA (7% versus 2%), and basal cell carcinoma (7% versus 4%) also occurred more frequently in monotherapy-arm versus D + T-arm patients (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). The incidence of other AEs of special interest (i.e. cardiotoxicities, ocular events, haemorrhages) was generally similar across the study arms (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Notably, the frequency of the most common D + T-associated AEs, including pyrexia, did not increase by >2% with an additional 13 months of follow-up since the last analysis (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online). Similarly, the incidence of key skin-related AEs, including palmoplantar hyperkeratosis, SCC/KA, and basal cell carcinoma, did not increase by >1% in the combination arm with extended follow-up, and no new primary melanomas were observed. Additionally, occurrence of events leading to dose interruptions (n = 122; 58%) or permanent discontinuation (n = 29; 14%) in D + T-arm patients increased by only 2% and 3%, respectively, and no new grade 5 AEs were observed.

Discussion

This 3-year landmark analysis of COMBI-d represents the longest follow-up for any phase 3 BRAFi/MEKi combination therapy trial and provides evidence that long-term clinical benefit and tolerability are achievable with D + T in a subset of patients with previously untreated BRAF V600E/K-mutant metastatic melanoma. Importantly, these findings do not support the idea that most patients treated by mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors rapidly develop deterioration due to secondary resistance. At the 3-year landmark, D + T continued to demonstrate superior benefit versus dabrafenib monotherapy (PFS, 22% versus 12%; OS, 44% versus 32%), even though 12% of monotherapy patients crossed over to receive D + T. Furthermore, many patients alive at 3 years remained on D + T.

The 3-year OS reported for D + T in this large phase 3 trial (44%) confirms preliminary results for the smaller corresponding patient subset in the randomized phase 2 BRF113220 trial (3-year OS, 38%) [11]. More generally, survival observed in the current analysis is consistent with previous findings for D + T in BRAF V600-mutant melanoma, since the 2-year OS reported here (52%) is similar to that reported in the randomized phase 3 COMBI-v study (51%) and in a pooled analysis across registration trials (53%) [14]. In this era of multiple drugs with significant activity in metastatic melanoma, clinical trial OS results may be confounded by availability of these therapies. In this analysis, of patients who received any post-progression systemic therapy, rates of subsequent anti-PD-1 use were similar between the D + T and monotherapy arms, and the rate of subsequent ipilimumab therapy was numerically higher in the monotherapy arm compared with the D + T arm. Thus, the 3-year OS observed with D + T in this study may be mostly attributed to the combination.

Direct comparisons of survival landmarks across trials of currently available melanoma treatments should be interpreted with caution due to differences in baseline characteristics between study populations, including the requirement for the presence of a BRAF V600E or V600K mutation in targeted therapy trials and the period of time during which studies were conducted (e.g. what treatments were available for subsequent therapy). However, in the absence of prospective head-to-head trials evaluating targeted versus checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapies, pivotal trials to date can be considered to provide outcomes trends for each drug class. Moving forward, it will be important to balance advantages of immunotherapy with anti-PD-1 (±anti-CTLA-4) and BRAFi/MEKi combinations.

Follow-up for anti-PD-1 checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapy regimens has lagged behind targeted therapy; 3-year landmark OS results, as reported here, are currently available only for early-phase trials. In a phase 1 study evaluating nivolumab monotherapy in 107 patients with previously treated melanoma, unselected for BRAF mutation status and 36% with elevated LDH, the 2-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 48%, 42%, and 34%, respectively [15]. In a phase 1 study of combined nivolumab plus ipilimumab, in 53 treatment-naive (60%) or previously treated (40%) patients with advanced melanoma (38% with elevated LDH), the 3-year OS was 68%; however, it should be noted that these results are preliminary [16] and randomized studies of the combination have shown a consistent 2-year survival of 64% [9, 17], less than this phase 1 landmark. As larger trials evaluating anti-PD-1 regimens in metastatic melanoma continue follow-up, preliminary trends in outcomes in a recent meta-analysis demonstrated no significant difference in OS between first-line BRAFi/MEKi and anti-PD-1 [18].

Altogether, data across trials of currently available therapies suggest that long-term survival profiles, at least up to 3 years, do not seem to confirm the hypothesis that only checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapy can provide durable benefit in patients with metastatic melanoma. Although initial clinical activity (e.g. response rates) differs between these therapeutic classes [3–9], the proportion of patients with a 3-year benefit may be similar; however this will need to be confirmed by additional analyses of checkpoint-inhibitor immunotherapies specifically in patients with BRAF-mutant disease. Furthermore, it is important to note that the plateau survival pattern observed with ipilimumab [2] has not yet been demonstrated with anti-PD-1 therapies and remains a potential survival pattern for BRAFi/MEKi.

It is now well established that efficacy of treatment of metastatic melanoma can differ depending on baseline patient characteristics. Analyses of BRAFi-naive patients treated with D + T in the phase 2 BRF113220 study and in a pooled analysis across D + T registration trials identified significant associations between baseline LDH and number of organ sites containing metastasis and clinical outcomes [11, 14]. Results from the current analysis support these findings, with the highest 3-year OS observed among patients with LDH < ULN and <3 organ sites containing metastasis (D + T, 62%; monotherapy, 45%). Patients with favourable baseline markers treated with frontline D + T are thus more likely to derive long-term benefit from this combination. Moreover, although 3-year survival was much lower in patients with LDH > ULN, the superiority of D + T over dabrafenib monotherapy was maintained (3-year OS, 25% versus 14%).

With an additional 13 months of follow-up from the previous OS analysis of COMBI-d, CR was achieved by an additional 5 D + T-arm patients, resulting in an updated CR rate of 18% and an overall response rate of 68% with the combination.

The safety profile of D + T with longer follow-up was similar to that observed in previous analyses, in which the combination was associated with a reduction in toxicities related to paradoxical activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway compared with BRAFi monotherapy [3, 4, 10–13]. Pyrexia remained the most common AE with D + T; however, it has been shown that pyrexia can be managed [19]. The frequency of key AEs did not greatly change with additional follow-up, including pyrexia and secondary malignancies, consistent with a recent report that incidence of D + T-associated AEs is highest during the first 6 months of treatment, declining thereafter [20]. Thus, although patients who remain on and benefit from treatment can become an increasingly biased population due to the disappearance of those with very poor tolerance and/or development of secondary resistance, long-term treatment with D + T appears to be well tolerated in the subgroup of patients who benefit.

This analysis, representing the longest follow-up for any phase 3 trial evaluating BRAFi/MEKi combination therapy, demonstrated that long-term survival is achievable with D + T in a relevant proportion of patients with BRAF V600-mutant metastatic melanoma and that long-term treatment with D + T is tolerable, with no new safety signals. These results support long-term use of D + T as a first-line treatment strategy for patients with advanced BRAF V600-mutant melanoma. However, a more comprehensive model including clinical factors as described here, along with molecular and/or immune-markers associated with efficacy, is needed to further guide treatment decisions (e.g. BRAFi/MEKi and checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy sequencing strategies) in this melanoma population. Continued follow-up planned for up to 5 years for COMBI-d will provide further understanding of the extent of benefit achievable with D + T in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Editorial assistance was provided by Jorge J. Moreno-Cantu (Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation). Medical writing assistance in the form of collating author comments, copyediting, and editorial assistance was provided by Amanda L. Kauffman, PhD (ArticulateScience LLC) and funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation.

Funding

This work was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation. No grant numbers apply.

Disclosure

GVL is a consultant advisor to Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck/MSD, Novartis, Roche. KTF has received personal fees and clinical trial support from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline. HG has received grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck/MSD, and Novartis, and personal fees for advisory board participation and travel from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, Merck/MSD, Novartis, and Amgen. CG has received grant support and personal fees for advisory board participation and presentations. AH has received trial grants from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Serono, Merck/MSD, Novartis, and Roche, has consulted for Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MedImmune, Merck/MSD, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis, OncoSec, Philogen, Provectus, Regeneron, and Roche, and has received honoraria from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MedImmune, Merck/MSD, Nektar Therapeutics, Novartis, OncoSec, Philogen, Provectus, Regeneron, and Roche. VC-S is a consultant for Merck/MSD, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Novartis. CL has received grants from Roche and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and personal fees for consultancy, advisory roles, speakers bureaus, and/or travel from Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, MSD, Amgen, and GlaxoSmithKline. MMa has received grant support from Roche and Novartis, and personal fees from Roche, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck. MMi has received fees for consulting from GlaxoSmithKline. AA has received personal fees from Novartis, Roche, Merck/MSD, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, and non-financial support from Roche and MSD. JH received personal fees for advisory board participation from Novartis, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Roche, and personal fees for travel from Novartis. JU has received personal fees from Roche, Merck/MSD, and Novartis, and non-financial support from Amgen. PM has received personal fees for lectures (including speakers bureaus), non-financial support, and has held board membership for Pierre Fabre, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck/MSD, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Amgen. DSc has received personal fees and patients’ fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, personal fees from Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Leo Pharma outside of the submitted work, and personal fees and patients’ fees from Roche, Merck/MSD, and Bristol-Myers Squibb outside of the submitted work. PN has received personal fees from Novartis. CR has consulted for Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Merck, Amgen, and Novartis. AR has received consulting fees from Amgen, Pfizer, Merck, and Roche, and holds stock ownership in Kite Pharma. MAD has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Roche/Genentech, and Sanofi, and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, and Sanofi. SRL was an employee of Novartis. JJL is a Novartis employee and shareholder. BM is a Novartis employee. J-JG has received personal fees for participating in advisory boards for Novartis, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Amgen, and Pierre Fabre. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Key Message

Our findings confirm superiority of combination dabrafenib and trametinib, compared with BRAF inhibition alone, and establish tolerability of the combination with extended follow-up. These data support long-term use of dabrafenib plus trametinib as a standard first-line targeted treatment of patients with BRAF V600-mutant metastatic melanoma.

References

- 1. Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL.. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 181: 193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C. et al. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1889–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H. et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J. et al. Two year estimate of overall survival in COMBI-v, a randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing the combination of dabrafenib (D) and trametinib (T) with vemurafenib (Vem) as first-line therapy in patients (pts) with unresectable or metastatic BRAF V600E/K mutation-positive cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51(Suppl. 3): S663, abstr 3301. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ascierto PA, McArthur GA, Dreno B. et al. Cobimetinib combined with vemurafenib in advanced BRAFV600-mutant melanoma (coBRIM): updated efficacy results from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1248–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schachter J, Ribas A, Long GV. et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab for advanced melanoma: final overall survival analysis of KEYNOTE-006. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: abstr 9504. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Atkinson V, Ascierto PA, Long GV. et al. Two-year survival and safety update in patients with treatment-naïve advanced melanoma (MEL) receiving nivolumab or dacarbazine in CheckMate 066. Presented at the Society for Melanoma Research 2015 International Congress, San Francisco, CA, 18–21 November 2015.

- 8. Weber JS, D'Angelo SP, Minor D. et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R. et al. Overall survival (OS) results from a phase III trial of nivolumab (NIVO) combined with ipilimumab (IPI) in treatment-naïve patients with advanced melanoma (CheckMate 067). Presented at American Association for Cancer Research Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, 1–5 April 2017; abstr CT075. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luke JJ, Ott PA.. New developments in the treatment of metastatic melanoma - role of dabrafenib-trametinib combination therapy. Drug Healthc Patient Saf 2014; 6: 77–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Flaherty KT, Infante JR, Daud A. et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition in melanoma with BRAF V600 mutations. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1694–1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Long GV, Weber JS, Infante JR. et al. Overall survival and durable responses in patients with BRAF V600-mutant metastatic melanoma receiving dabrafenib combined with trametinib. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H. et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1877–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J. et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Long GV, Grob J, Nathan P. et al. Factors predictive of response, disease progression, and overall survival after dabrafenib and trametinib combination treatment: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1743–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hodi FS, Kluger HM, Sznol M. et al. Durable, long-term survival in previously treated patients with advanced melanoma (MEL) who received nivolumab (NIVO) monotherapy in a phase I trial. Cancer Res 2016; 76: abstr CT001. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hodi FS, Chesney J, Pavlick AC. et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab alone in patients with advanced melanoma: 2-year overall survival outcomes in a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1558–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Menzies AM, Ashworth MT, Swann S. et al. Characteristics of pyrexia in BRAFV600E/K metastatic melanoma patients treated with combined dabrafenib and trametinib in a phase I/II clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grob JJ, Flaherty K, Long GV. et al. Pooled analysis of safety over time and link between adverse events and efficacy across combination dabrafenib and trametinib (D+T) registration trials. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: abstr 9534. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.