Abstract

Background

Infiltrating low-grade gliomas (LGG; WHO grade 2) typically present with seizures in young adults. LGGs grow continuously and usually transform to higher grade of malignancy, eventually causing progressive disability and premature death. The effect of up-front surgery has been controversial and the impact of molecular biology on the effect of surgery is unknown. We now present long-term results of upfront surgical resection compared with watchful waiting in light of recently established molecular markers.

Materials and methods

Population-based parallel cohorts were followed from two Norwegian university hospitals with different surgical treatment strategies and defined geographical catchment regions. In region A watchful waiting was favored while early resection was favored in region B. Thus, the treatment strategy in individual patients depended on their residential address. The inclusion criteria were histopathological diagnosis of supratentorial LGG from 1998 through 2009 in patients 18 years or older. Follow-up ended 1 January 2016. Making regional comparisons, the primary end-point was overall survival.

Results

A total of 153 patients (66 from region A, 87 from region B) were included. Early resection was carried out in 19 (29%) patients in region A compared with 75 (86%) patients in region B. Overall survival was 5.8 years (95% CI 4.5–7.2) in region A compared with 14.4 years (95% CI 10.4–18.5) in region B (P < 0.01). The effect of surgical strategy remained after adjustment for molecular markers (P = 0.001).

Conclusion

In parallel population-based cohorts of LGGs, early surgical resection resulted in a clinical relevant survival benefit. The effect on survival persisted after adjustment for molecular markers.

Keywords: astrocytoma, brain neoplasm, low-grade glioma, population based, survival, treatment outcome

Introduction

Infiltrating low-grade gliomas (LGG) are slow growing brain tumors typically presenting with seizures in young or middle-aged adults. LGGs grow continuously and usually transform to higher grades of malignancy, eventually causing progressive disability and premature death [1].

The management of LGGs has long been controversial, both with respect to surgical and oncological management and timing of treatment [1, 2]. Although case-series have reported associations between extent of surgical resection and survival, a causal relationship is impossible to establish from such uncontrolled studies [3, 4]. Due to concerns if clinical equipoise exists [1, 4–8], and need for long follow-ups [9], a randomized controlled trial comparing surgery to no surgery is not to be expected. Also, patients hesitate to enroll in randomized controlled trials with radically different options involving brain tumor surgery [10]. Our population-based parallel cohort study comparing outcomes in two Norwegian regions with opposite surgical management traditions was a landmark paper in surgical management of LGG [5]. The study demonstrated a marked survival advantage in favor of early surgical resection compared with watchful waiting. Although practice changing (including in the region that used to favor watchful waiting), criticism included risk of histopathological sampling bias when comparing stereotactic biopsies to tissue samples from resection [11]. Even though the population-based setting presumably would ensure well-balanced groups from the two regions, more tumors from the region advocating early and extensive surgery had a favorable histopathological subtype (i.e. containing oligo-component) [5, 8, 9, 12]. Also, since median survival was not reached in one of the cohorts, it still remains unknown how much surgery improves survival in the longer term [8].

The recently updated WHO classification system now incorporates molecular markers in LGG classification [13]. With molecular characterization the possibility of diagnostic sampling errors is much reduced, as these are early, common events with homogenous distribution within the tumor [14]. 1p19q codeletion in combination with IDH mutation now define oligodendroglioma, a diagnosis that used to be associated with considerable uncertainty based on morphological classification alone [15]. Also, although IDH wild-type LGGs are still classified as LGGs, they frequently present a much more malignant phenotype [16, 17]. However, the impact of surgery in the recently defined molecular subgroups is still unknown [13, 16, 17].

In the present study, we now provide long-term survival data and assess molecular markers in our population-based parallel cohorts of LGG.

Methods

Study design and patients

In a retrospective population-based parallel cohort study, we assessed survival in patients with LGGs treated at two Norwegian university hospitals with completely different surgical treatment strategies, as described earlier [5]. The two hospitals served exclusively in defined geographical catchment regions. The hospital in region A favored biopsy and watchful waiting while early 3D ultrasound guided resection in general anesthesia was the preferred strategy in region B. Thus, the treatment strategy in individual patients highly depended on their residential address.

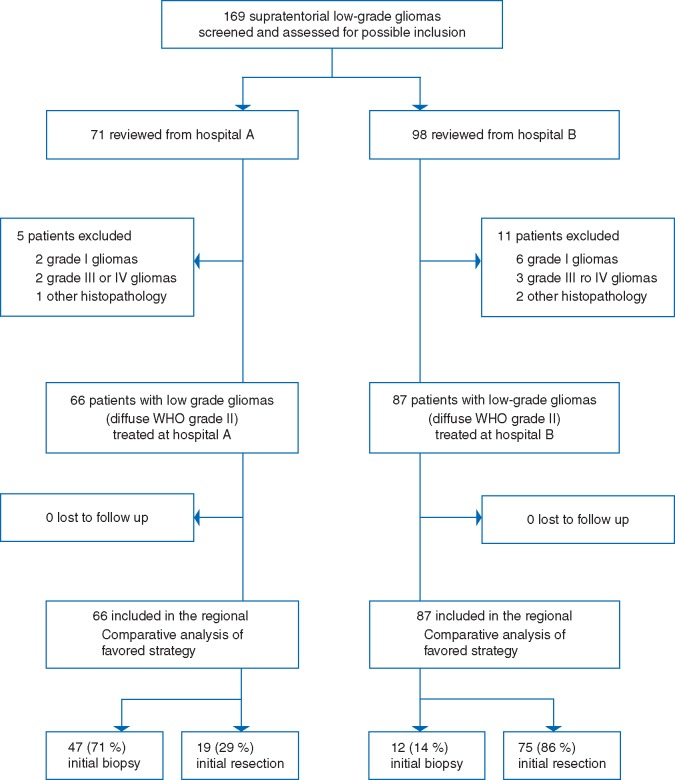

The inclusion criteria were histopathological verification of supratentorial LGG in adult patients (18 years or older) in the period from 1998 through 2009 using the WHO 2007 classification [18]. To minimize classification bias a blinded review was carried out where a neuropathologist from region A reviewed all LGGs diagnosed at region B and vice versa. Discordant diagnoses were settled in a consensus meeting [5, 6]. Our final sample included 153 consecutive patients (66 from region A and 87 from region B) with LGGs as seen from flow chart in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patient inclusion.

Assessment of molecular markers

The assessment of molecular markers aimed at assigning patients to one of three molecular groups: (i) the low-risk group being IDH mutated, 1p19q codeleted, (ii) the intermediate-risk group being IDH mutated and 1p19q non-codeleted, and (iii) the high-risk group being IDH wild-type [16]. At the hospital in region A the 1p19q codeletion and IDH status were determined using multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA) directly since the limited amount of tissue available did not allow for step-wise integrated approach [19]. Samples classified as IDH wild-type after MLPA assessment were subject to PCR and DNA sequencing for IDH1 and IDH2 mutations. At hospital in region B an integrated approach was used [19], with immunohistochemistry for IDH1 R132H and alpha thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome X-linked (ATRX) protein expression. In this initial step, if simultaneous IDH mutation and ATRX loss were observed no further analyses were carried out; and patients were classed as IDH mutated, 1p19q non-codeleted. Samples classified as IDH wild-type after immunohistochemistry were subject to PCR and DNA sequencing for IDH1 and IDH2 mutations. In samples with IDH mutation and ATRX presence, we carried out fluorescence insitu hybridization (FISH) to confirm the 1p19q codeletion. However, in three cases we assumed 1p19q codeletion based on IDH and ATRX presence, but without FISH confirmation since no additional tissue was available. Further details on the assessment of molecular markers are available in supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Follow-up and outcomes

All Norwegian citizens have a unique identification number making them traceable in the Norwegian population registry. With the use of this registry the patients’ status (dead/alive) and date of death was verified in all patients. Follow-up ended 1 January 2016. No patients were lost to follow up with respect to the primary end-point. The primary end-point was overall survival making direct regional comparison between cohorts (i.e. analyzing strategy, not introducing selection bias).

Statistical analyses

For analyses, we used GraphPad Prism version 6 and SPSS version 21.0. We used Fisher’s exact test for comparing results from 2× 2 tables. For other categorical data, we used the χ2 test. For continuous data, comparison of groups was carried out with independent samples t-test. Overall survival is presented as Kaplan–Meier plots and the log-rank test was used for between groups comparison. Cox multivariable survival analysis was carried out to adjust for important prognostic factors, including molecular markers. All tests are two-sided and statistical significance was set to P < 0.05.

Statements

The Regional Committee for Medical Research in Central Norway Ethical approved the study (reference: 2014/1674). The committee waived the need for informed consent. The study is reported based on criteria from the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement [20].

Results

Characteristics of patients and tumors at baseline

The age adjusted incidence rate was 1.2 per 100 000 in both regions. Baseline characteristics were presented in the initial study [5], and the most important ones are presented again along with IDH mutation status and 1p19q codeletion status in Table 1. More detailed analyses of molecular profile in relation to clinical factors are available in supplementary Tables S1–S3 and Figures S1 and S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. There were neither significant differences in known prognostic factors such as age, tumor size, contrast enhancement, functional level, nor histopathological subtypes. In 64 out of 66 patients (97%) from region A and in 81 out of 87 patients (93%) from region B we had available tissue for molecular analyses. The molecular markers were not significantly different between cohorts. Interestingly, the trend toward overrepresentation of oligodendroglial tumors in region B as defined from the 2007 WHO classification system changed when analyzed according to 1p19q codeletion status.

Table 1.

Comparisons of baseline factors and molecular markers between cohorts

| Region A (n=66) | Region B (n=87) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 45 (15) | 44 (16) | 0.67 |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.33 | ||

| Female | 25 (38) | 40 (46) | |

| Male | 41 (62) | 47 (54) | |

| KPS ≥80, n (%) | 51 (77) | 71 (82) | 0.55 |

| Contrast enhancement, n (%) | 13 (20) | 15 (17) | 0.83 |

| Histopathology, n (%) | 0.19 | ||

| Astrocytoma | 55 (83) | 62 (71) | |

| Oligodendroglioma | 6 (9) | 16 (19) | |

| Oligoastrocytoma | 5 (8) | 9 (10) | |

| Tumor >6 cm in diameter, n (%) | 19 (29) | 24 (28) | 1.00 |

| Tumor crossing midline, n (%) | 10 (15) | 11 (13) | 0.81 |

| Neurological deficit, n (%) | 17 (26) | 25 (29) | 0.72 |

| IDH status, n (%) | 0.46 | ||

| Mutated | 48/64 (75) | 56/81 (69) | |

| Wild-type | 16/64 (25) | 25/81 (31) | |

| Undetermined/missing | 2 | 6 | |

| 1p19q codeletion, n (%) | 23/64 (36) | 20/81 (25) | 0.14 |

| Molecular-risk group, n (%) | 0.33 | ||

| Low | 23 (36) | 20 (25) | |

| Intermediate | 25 (39) | 36 (44) | |

| High | 16 (25) | 25 (31) |

Contrast enhancement indicates all types, including subtle patchy or diffuse contrast enhancement and should not be confused with only significant nodular or ring-like contrast enhancement. The molecular risk-groups are as follows: (i) low risk infers IDH mutated and 1p19q codeleted; (ii) intermediate risk infers IDH mutated and 1p19q non-codeleted; and (iii) high-risk infers IDH wild-type.

KPS, Karnofsky performance status; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase.

Treatment-related factors

As seen from Figure 1 and Table 2, early surgical resection was carried out in 19 patients (29%) in region A compared with 75 patients (86%) in region B (P < 0.001). As seen in Table 2, there were no regional differences in administration of either early or late radio- or chemotherapy, including early radiotherapy and PCV. Furthermore, the fraction of patients undergoing later surgical resections was similar between cohorts.

Table 2.

Treatment related factors in the parallel cohorts

| Region A (n=66) | Region B (n=87) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early resection, n (%) | 19 (29) | 75 (86) | <0.001 |

| Number of new/repeated resections, n (%) | 0.11 | ||

| 0 | 42 (63) | 49 (56) | |

| 1 | 18 (27) | 24 (28) | |

| 2 | 1 (2) | 8 (9) | |

| 3 or more | 5 (8) | 6 (7) | |

| Ever resection, n (%) | 36 (55) | 77 (89) | <0.001 |

| Early chemotherapy, n (%) | 14 (21) | 18 (21) | 1.00 |

| Ever chemotherapy, n (%) | 44 (67) | 42 (48) | 0.32 |

| Early radiotherapy, n (%) | 20 (30) | 37 (43) | 0.13 |

| Ever radiotherapy, n (%) | 50 (76) | 57 (66) | 0.21 |

| Early radio- and chemotherapy, n (%) | 11 (17) | 13 (15) | 0.82 |

| Early radiotherapy and PCV, n (%) | 2 (3) | 8 (9) | 0.19 |

Early chemotherapy indicates treatment within 6 months following histopathological diagnosis. PCV denotes procarbazine, CCNU (lomustine) and Vincristine. Combined radio- and chemotherapy means concomitant or succeeding treatment upfront.

Survival

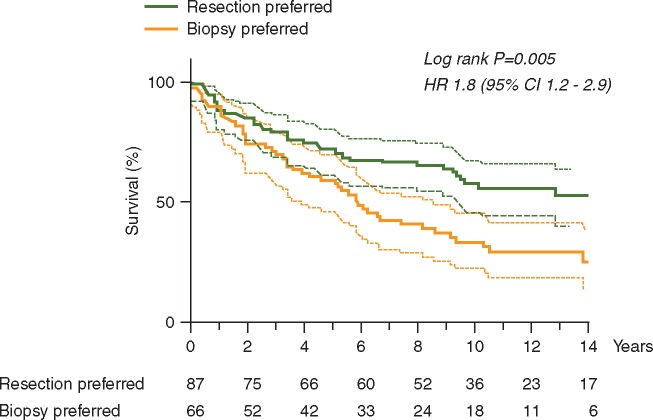

Overall survival was significantly worse in region A advocating watchful waiting (Figure 1, P = 0.005) with a median survival of 5.8 years (95% CI 4.5–7.2) compared with 14.4 years (95% CI 10.4–18.5) in region B advocating early resections. As seen in Figure 2, adjustment for molecular factors did not alter the results. In supplementary Tables S4, available at Annals of Oncology online, there is an overview of 2, 5, 7 and 10 years actual and estimated survival rates in both cohorts.

Figure 2.

Survival analysis comparing cohorts, where region A preferred biopsy while region B preferred early resection. In region A the median survival was 5.8 years (95% CI 4.5–7.2) compared with 14.4 years (95% CI 10.4–18.5) in region B.

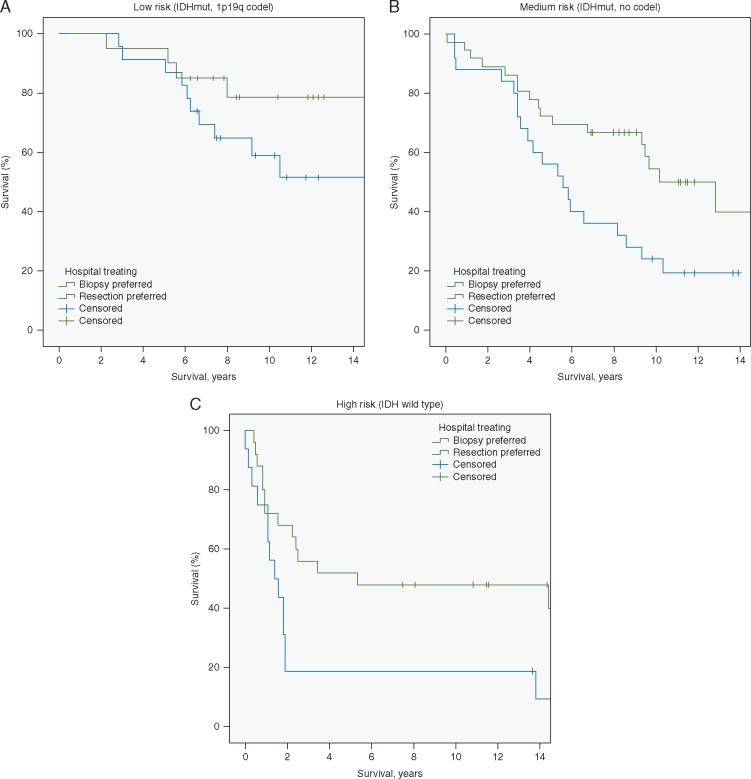

As seen in Figure 3, the survival benefit of the active surgical strategy remained after adjusting for molecular-risk group (P = 0.001). In sensitivity analyses of survival presented in supplementary Figures S3 and S4, available at Annals of Oncology online we analyzed younger patients with seizures only and we adjusted for molecular-risk group in addition to a widely used clinical LGG risk-score (i.e. the Pignatti score) [12]. In sum, these additional analyses did not alter results. Adding year of treatment to the models also did not alter results (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Survival in cohorts (A–C) with adjustment for molecular risk-group (log-rank test, P = 0.001). Results are presented stratified according to risk groups (A) low-risk (B) medium-risk and (C) high-risk group. (A) IDH mutated, 1p19 codeleted LGGs (n =43). Median survival was not reached. (B) IDH mutated, non-codeleted LGGs (n =61). Median survival in region A was 5.6 years (95% CI 3.5–7.6) compared with 10.2 year (95% CI 6.9–13.4) in region B. (C) IDH wild-type LGGs (n=41). Median survival in region A was 1.4 year (95% CI 0.6–2.2) compared with 5.3 year (95% CI 0.0–20.0) in region B.

Discussion

In this updated analysis of our unique population-based parallel cohorts we demonstrate that early resection is associated with a clinically relevant survival benefit when compared with watchful waiting in LGGs. Cohorts were balanced at baseline and adjustment for molecular markers did not alter results. Thus, our findings are in line and strengthen the results from our previous publication [5].

A more definitive effect size assessment can better guide decision-making for physicians and patients that need to estimate the risks and benefits of surgery in a given case. However, since some patients underwent resection in region A and some had biopsy only in region B, the observed survival benefit of early surgical resection is presumably a conservative measure. The debate on the extent of surgical resection needed in order to result in a clinically relevant survival benefit is not settled. Retrospective uncontrolled studies report a clear advantage with radiological complete resection, although often not achievable [3, 4, 21]. Others have emphasized that a residual tumor volume <15 ml must be achieved to have a beneficial survival effect [22]. However, extent of resection is not random and selection bias may clearly be an issue in such studies. Unfortunately, we are not able to provide data on extents of resection in this study due to the lack of postoperative MR and lack of digitalization of images before 2005–2006 in region B. However, based on the observed large effect on a population level it seems safe to conclude that aiming at early and extensive surgical resections should be considered in the vast majority of patients with suspected LGGs. Post hoc analyses also demonstrated a benefit of early surgical resection on young patients with seizures only, a patient group where some still advocate watchful waiting.

It should be acknowledged that some LGGs are not eligible for a meaningful extent of resection with an acceptable risk. However, an overall treatment strategy in favor of watchful waiting cannot be recommended in patients eligible for resection and should only be done with informed consent, and preferably within clinical trials. Also, the logic behind postponing treatment until growth is detected can be questioned since LGGs always grow, although some grow so slowly that growth is not detected with crude measures and relatively short follow-up times, while others transform without causing additional symptoms [23–25]. Finally, malignant transformation usually occurs with time but extensive surgical resection may delay this process [5].

With modern surgical tools and techniques, including intraoperative MRI [21], 3D-ultrasound guided resection (as used in region B in the present study) [5], and mapping techniques [1], morbidity and surgical extent of resection is perhaps more predictable than earlier. Also there was no difference in health-related quality of life in patients still alive from the two cohorts, as reported previously [7].

The fraction of patients harboring LGGs with IDH mutations is comparable or slightly lower than recently published clinical studies, including a large Chinese population-based study [9, 26, 27]. Thus, our population-based cohorts seems representative of the LGG reported in other clinical settings as well. In many of our IDH wild-type cases no further tissue was available, and consequently we did not perform additional analyses on TERT mutation to further differentiate between the IDH wild-type tumors between regions [17]. Although one should be careful of reading too much into small subgroup analyses, the exploratory subgroup analyses indicate that surgical resection is effective in all molecular subgroups.

Limitations

The methodological concept behind our study is outlined in detail in our previous publication [5]. The main limitation of our study is the lack of randomization, but as emphasized earlier a randomized study is highly unlikely to ever be carried out. With this study there is even less clinical equipoise to this topic. The retrospective assessment is also a limitation with respect to baseline variables and nonstandardized documentation, but the primary end-point (i.e. overall survival) is robust regardless of this. As described earlier, disease-specific death was not assessed and with a long follow-up some patients may die of unrelated causes [5]. However, in Norway the difference between overall and disease-specific survival for adults with primary brain tumors does not exceed 2% during the first 15 years of observation [28]. Another criticism we faced was that the cohort from region A did so poorly that they could not be representative for a LGG cohort, but this speculation is refuted after molecular classification. In fact, survival in region A compares well to historical Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data from the years before extensive surgery was as often attempted or achieved and from other studies studying biopsies as a surgical policy [22, 29, 30].

Our population-based data from two geographical regions served by two different neurosurgical departments with highly different treatment traditions ensured comparable and balanced groups. Also, we have analyzed results conservatively with only regional comparisons to avoid introducing selection bias to our study. Diagnostic sampling bias may be an issue when comparing biopsy to surgical resection [11], but this would be unavoidable in any study comparing biopsy with resection in a histopathological defined group. After assessment of the molecular markers that are early, common events we are now reassured that tumors were comparable from a biological point of view, as expected in a population-based study [14]. Thus, the potential risk of histopathological sampling bias that may result when comparing stereotactic biopsies to tissue samples from resection is much reduced by analyzing molecular markers. However, the molecular markers were assessed differently between regions and due to the approach in region B there could be a slight underestimation of 1p19q codeleted tumors.

In conclusion, there is a considerable and sustained survival advantage associated with early resection compared with a strategy of watchful waiting in unselected patients with LGGs. The survival benefit remained after adjustment for molecular markers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lisa M. Sagberg for assistance with data collection and Nathalie Reuter and Kristian Kobbenes Starheim for their advice on molecular findings.

Funding

The study was funded by the St. Olavs Hospital Research Fund (grant number N/A), the Swedish Government and the County Councils Economic Support of Research (ALF-agreement, ALFGBG-695611) and the Norwegian Cancer Society (grant number 5703787). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

References

- 1. Sanai N, Chang S, Berger MS.. Low-grade gliomas in adults. J Neurosurg 2011; 1: 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Veeravagu A, Jiang B, Chang SD. et al. Biopsy versus resection for the management of low-grade gliomas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 4: Cd009319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Capelle L, Fontaine D, Mandonnet E. et al. Spontaneous and therapeutic prognostic factors in adult hemispheric World Health Organization Grade II gliomas: a series of 1097 cases. J Neurosurg 2013; 118: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith JS, Chang EF, Lamborn KR. et al. Role of extent of resection in the long-term outcome of low-grade hemispheric gliomas. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1338–1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jakola AS, Myrmel KS, Kloster R. et al. Comparison of a strategy favoring early surgical resection vs a strategy favoring watchful waiting in low-grade gliomas. JAMA 2012; 308: 1881–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jakola AS, Unsgard G, Myrmel KS. et al. Surgical strategy in grade II astrocytoma: a population-based analysis of survival and morbidity with a strategy of early resection as compared to watchful waiting. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2013; 155: 2227–2235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jakola AS, Unsgard G, Myrmel KS. et al. Surgical strategies in low-grade gliomas and implications for long-term quality of life. J Clin Neurosci 2014; 21: 1304–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Markert JM. The role of early resection vs biopsy in the management of low-grade gliomas. JAMA 2012; 308: 1918–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buckner JC, Shaw EG, Pugh SL. et al. Radiation plus procarbazine, CCNU, and vincristine in low-grade glioma. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 1344–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Myrseth E, Moller P, Pedersen PH, Lund-Johansen M.. Vestibular schwannoma: surgery or gamma knife radiosurgery? A prospective, nonrandomized study. Neurosurgery 2009; 64: 654–661; discussion 661–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jackson RJ, Fuller GN, Abi-Said D. et al. Limitations of stereotactic biopsy in the initial management of gliomas. Neuro-Oncology 2001; 3: 193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pignatti F, van den Bent M, Curran D. et al. Prognostic factors for survival in adult patients with cerebral low-grade glioma. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20: 2076–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G. et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131: 803–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suzuki H, Aoki K, Chiba K. et al. Mutational landscape and clonal architecture in grade II and III gliomas. Nat Genet 2015; 47: 458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aldape K, Simmons ML, Davis RL. et al. Discrepancies in diagnoses of neuroepithelial neoplasms. Cancer 2000; 88: 2342–2349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD. et al. Comprehensive, Integrative Genomic Analysis of Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2481–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eckel-Passow JE, Lachance DH, Molinaro AM. et al. Glioma Groups Based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT Promoter Mutations in Tumors. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2499–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Louis D, Ohgaki H, Wiestler O. et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol 2007; 114: 97–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reuss DE, Sahm F, Schrimpf D. et al. ATRX and IDH1-R132H immunohistochemistry with subsequent copy number analysis and IDH sequencing as a basis for an "integrated" diagnostic approach for adult astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma and glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol 2015; 129: 133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M. et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Claus EB, Horlacher A, Hsu L. et al. Survival rates in patients with low-grade glioma after intraoperative magnetic resonance image guidance. Cancer 2005; 103: 1227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roelz R, Strohmaier D, Jabbarli R. et al. Residual tumor volume as best outcome predictor in low grade glioma – a nine-years near-randomized survey of surgery vs. biopsy. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 32286.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pallud J, Mandonnet E, Duffau H. et al. Prognostic value of initial magnetic resonance imaging growth rates for World Health Organization grade II gliomas. Ann Neurol 2006; 60: 380–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rees J, Watt H, Jager HR. et al. Volumes and growth rates of untreated adult low-grade gliomas indicate risk of early malignant transformation. Eur J Radiol 2009; 72: 54–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cochereau J, Herbet G, Rigau V, Duffau H.. Acute progression of untreated incidental WHO Grade II glioma to glioblastoma in an asymptomatic patient. J Neurosurg 2016; 124: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cordier D, Goze C, Schadelin S. et al. A better surgical resectability of WHO grade II gliomas is independent of favorable molecular markers. J Neurooncol 2015; 121: 185–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang HY, Tang K, Liang TY. et al. The comparison of clinical and biological characteristics between IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2016; 35: 86.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johannesen TB, Langmark F, Lote K.. Cause of death and long-term survival in patients with neuro-epithelial brain tumours: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39: 2355–2363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Claus EB, Black PM.. Survival rates and patterns of care for patients diagnosed with supratentorial low-grade gliomas. Cancer 2006; 106: 1358–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brasil Caseiras G, Ciccarelli O, Altmann DR. et al. Low-grade gliomas: six-month tumor growth predicts patient outcome better than admission tumor volume, relative cerebral blood volume, and apparent diffusion coefficient. Radiology 2009; 253: 505–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.