Abstract

Background

Chemotherapy remains a viable option for the management of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) despite recent advances in molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy. We evaluated the efficacy of oral 5-fluorouracil-based S-1 as second- or third-line therapy compared with standard docetaxel therapy in patients with advanced NSCLC.

Patients and methods

Patients with advanced NSCLC previously treated with ≥1 platinum-based therapy were randomized 1 : 1 to docetaxel (60 mg/m2 in Japan, 75 mg/m2 at all other study sites; day 1 in a 3-week cycle) or S-1 (80–120 mg/day, depending on body surface area; days 1–28 in a 6-week cycle). The primary endpoint was overall survival. The non-inferiority margin was a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.2.

Results

A total of 1154 patients (577 in each arm) were enrolled, with balanced patient characteristics between the two arms. Median overall survival was 12.75 and 12.52 months in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively [HR 0.945; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.833–1.073; P = 0.3818]. The upper limit of 95% CI of HR fell below 1.2, confirming non-inferiority of S-1 to docetaxel. Difference in progression-free survival between treatments was not significant (HR 1.033; 95% CI 0.913–1.168; P = 0.6080). Response rate was 8.3% and 9.9% in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively. Significant improvement was observed in the EORTC QLQ-C30 global health status over time points in the S-1 arm. The most common adverse drug reactions were decreased appetite (50.4%), nausea (36.4%), and diarrhea (35.9%) in the S-1 arm, and neutropenia (54.8%), leukocytopenia (43.9%), and alopecia (46.6%) in the docetaxel arm.

Conclusion

S-1 is equally as efficacious as docetaxel and offers a treatment option for patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC.

Clinical trial number

Japan Pharmaceutical Information Center, JapicCTI-101155.

Keywords: docetaxel, non-inferiority, previously treated NSCLC, S-1, phase 3 study

Introduction

Lung cancer remains one of the most lethal cancers worldwide. Chemotherapy is the standard treatment for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and there are specific treatment options based on molecular mutation status according to clinical practice guidelines. In the absence of a driver oncogene, anti-programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed death-1 (PD-1) immunotherapy is now a standard second-line treatment option [1–3]. For patients who have failed or are not eligible for immunotherapy, docetaxel—with or without angiogenesis inhibition—or pemetrexed are other standard therapies in case of relapsed NSCLC. However, according to the results of earlier studies in this setting, docetaxel is associated with a relatively high incidence of grade 3/4 neutropenia and febrile neutropenia [4, 5].

S-1 is an oral cytotoxic drug that comprises tegafur (a prodrug of 5-fluorouracil and the main cytotoxic effector of S-1), gimeracil (a potent dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase inhibitor), and oteracil potassium (an inhibitor of phosphorylation of 5-fluorouracil in the gastrointestinal tract) in a molar ratio of 1 : 0.4 : 1. S-1 monotherapy is a potentially efficacious treatment for advanced NSCLC in light of promising data from a phase 2 study of S-1 as second-line treatment for NSCLC that showed an overall response rate of 12.5% and a median overall survival (OS) of 8.2 months [6]. We hypothesized that S-1 is equally as efficacious as docetaxel. In this randomized phase 3 study, we compared S-1 with docetaxel in patients with previously treated advanced NSCLC, with a primary objective of establishing non-inferiority of S-1 in OS.

Methods

Study design and patients

This randomized, open-label, phase 3 non-inferiority study was conducted at 84 medical centers in China, Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. Patients were randomized 1 : 1 to receive either S-1 or docetaxel. The protocol summary is available in supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Key eligibility criteria were age ≥20 years; locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status ≤2; appropriate organ function; and ≤2 previous chemotherapy regimens, including ≥1 platinum-based regimen [if patients had received an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), gefitinib/erlotinib, then three previous regimens were allowed]. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating center. All patients provided written informed consent before participation.

Treatment

S-1 was given orally, twice daily, after meals, at a dose based on body surface area (<1.25 m2, 80 mg/day; ≥1.25 to <1.5 m2, 100 mg/day; ≥1.5 m2, 120 mg/day) for 4 weeks in a 6-week cycle. Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (or 60 mg/m2 when given at study sites in Japan) was given intravenously on day 1 of a 3-week cycle.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint was OS, which was defined as the time after randomization until death from any cause. Secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS), defined as the time from randomization until either disease progression or death from any cause (whichever was earlier); time to treatment failure, defined as the time from randomization to the earliest date of disease progression, death from any cause, or discontinuation of study treatment; and response rate, defined as the proportion of patients whose best overall response was complete response or partial response.

Tumor response was assessed in patients with measurable lesions according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1. Adverse events (AEs) were evaluated according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0. Patient-reported outcomes were based on the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core-30 (QLQ-C30) and the lung cancer-specific questionnaire module (QLQ-LC13) at baseline and every 6 weeks during treatment.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective was to establish non-inferiority in OS of S-1 compared with docetaxel. With an expected median OS of 12 months in both arms 1.5 years after the final randomization and a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.2 as the non-inferiority margin, a total of 944 events (in both arms) and 568 patients per arm were required to establish non-inferiority with a one-sided significance level of 0.025 and an 80% power. The non-inferiority margin was determined by the effect-retention method [7], guided by results of the TAX317 trial [4], with an HR of docetaxel to best supportive care of 0.61. In the present study, we assumed that at least 60% of the efficacy of docetaxel over best supportive care would be acceptable as a non-inferiority margin, which corresponds approximately to an HR of 1.2.

The primary efficacy analysis was based on the full analysis set (FAS), consisting of all randomized patients except those with a major protocol deviation. The per-protocol set consisted of all FAS patients without any deviations in eligibility criteria or use of prohibited concomitant therapies. Safety was analyzed for the patients who received at least one dose of the study drug.

The Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate the HR for primary analysis. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and response rates were compared using the χ2 test. Quality of life (QoL) was analyzed using a linear mixed-effects model. Subgroup analyses were carried out to assess treatment effects by pre-specified background factors. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.2.

Results

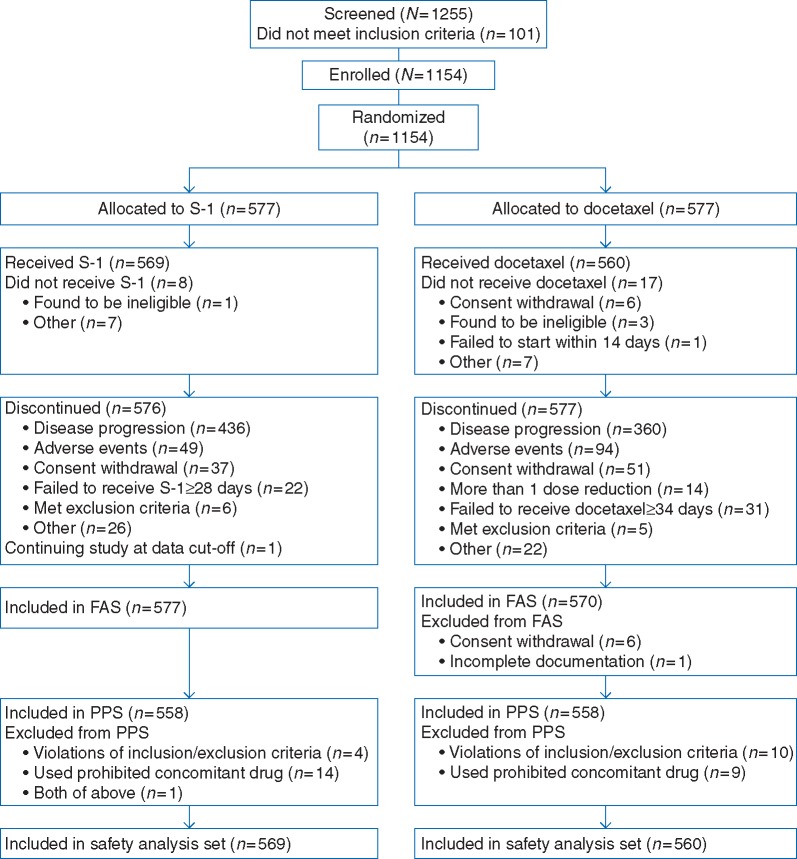

Between July 2010 and June 2014, 1154 of 1255 screened patients were enrolled and randomized, with 577 patients to each arm (Figure 1). The FAS consisted of 577 patients in the S-1 arm and 570 patients in the docetaxel arm. The study drug was administered to 1129 patients (S-1, 569; docetaxel, 560). Baseline characteristics were well balanced between arms (Table 1); 70.9% of EGFR mutation positive patients (95 in the S-1 arm, 93 in the docetaxel arm) received EGFR-TKI before the study (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Median number of treatment cycles was 2.0 (range 1–27) in the S-1 arm and 3.0 (range 1–41) in the docetaxel arm. At the data cut-off date (20 November 2015), there were 479 (83.0%) and 487 (85.4%) deaths in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively, and median follow-up time was 30.75 months.

Figure 1.

Study disposition. FAS, full analysis set; PPS, per-protocol set.

Table 1.

Baseline and demographic data

| S-1 | Docetaxel | |

|---|---|---|

| N = 577 | N = 570 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 388 (67.2) | 381 (66.8) |

| Female | 189 (32.8) | 189 (33.2) |

| Age (years), median (range) | 62 (23−85) | 62 (28−82) |

| Body surface area (m2), median (range) | 1.670 (1.17–2.12) | 1.670 (1.21–2.30) |

| Previous chemotherapy regimens | ||

| 1 | 350 (60.7) | 357 (62.6) |

| 2 | 178 (30.8) | 169 (29.6) |

| 3 | 49 (8.5) | 44 (7.7) |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 200 (34.7) | 207 (36.3) |

| 1 | 365 (63.3) | 350 (61.4) |

| 2 | 12 (2.1) | 13 (2.3) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Japanese | 357 (61.9) | 358 (62.8) |

| Chinese | 193 (33.4) | 192 (33.7) |

| Korean | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Taiwanese | 22 (3.8) | 16 (2.8) |

| Other | 4 (0.7) | 4 (0.7) |

| Previous EGFR TKI | ||

| No | 442 (76.6) | 440 (77.2) |

| Yes | 135 (23.4) | 130 (22.8) |

| Surgery | ||

| No | 470 (81.5) | 456 (80.0) |

| Yes | 107 (18.5) | 114 (20.0) |

| Radiation therapy | ||

| No | 358 (62.0) | 330 (57.9) |

| Yes | 219 (38.0) | 240 (42.1) |

| Histology type | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 430 (74.5) | 431 (75.6) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 105 (18.2) | 97 (17.0) |

| Large cell carcinoma | 10 (1.7) | 7 (1.2) |

| Other | 31 (5.4) | 35 (6.1) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stage | ||

| IIIB | 48 (8.3) | 35 (6.1) |

| IV | 528 (91.5) | 535 (93.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Ever | 395 (68.5) | 383 (67.2) |

| Never | 182 (31.5) | 187 (32.8) |

| EGFR mutation | ||

| Positive | 135 (23.4) | 130 (22.8) |

| Negative | 350 (60.7) | 347 (60.9) |

| Unknown | 92 (15.9) | 93 (16.3) |

| Target lesions | ||

| No | 80 (13.9) | 53 (9.3) |

| Yes | 496 (86.0) | 517 (90.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise specified.

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

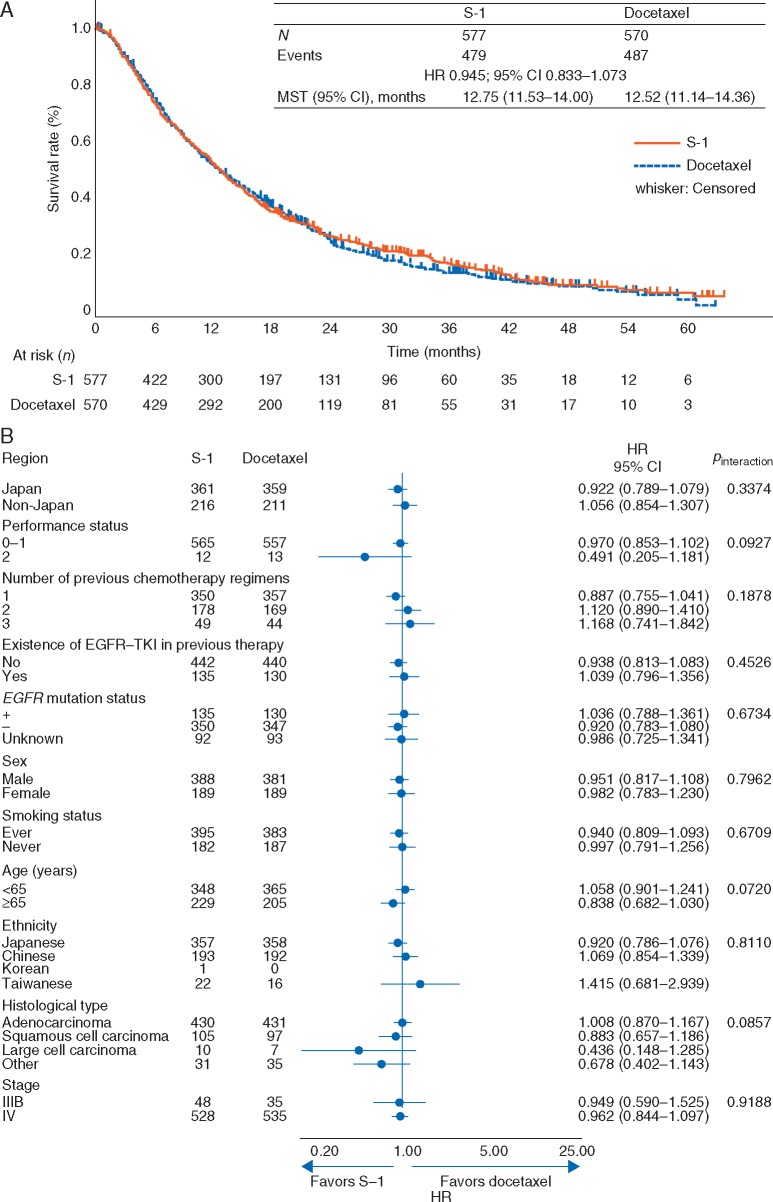

Kaplan–Meier curve and forest plot of OS are shown in Figure 2. Median OS was 12.75 and 12.52 months in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively (HR 0.945, 95% CI 0.833–1.073; P = 0.3818), confirming non-inferiority of S-1 to docetaxel. HRs of OS by randomization factor are summarized in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. Supportive analysis in the per-protocol set (HR 0.963, 95% CI 0.847–1.095) and all randomized patients (HR 0.940, 95% CI 0.829−1.067; supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) showed similar results to that of the FAS. In OS subgroup analysis, no interactions were observed among subgroups (Figure 2B). The stratified HR for Japanese and non-Japanese patients is shown in supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Figure 2.

(A) Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival (FAS); (B) Forest plot for overall survival. CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FAS, full analysis set; HR, hazard ratio; MST, median survival time; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

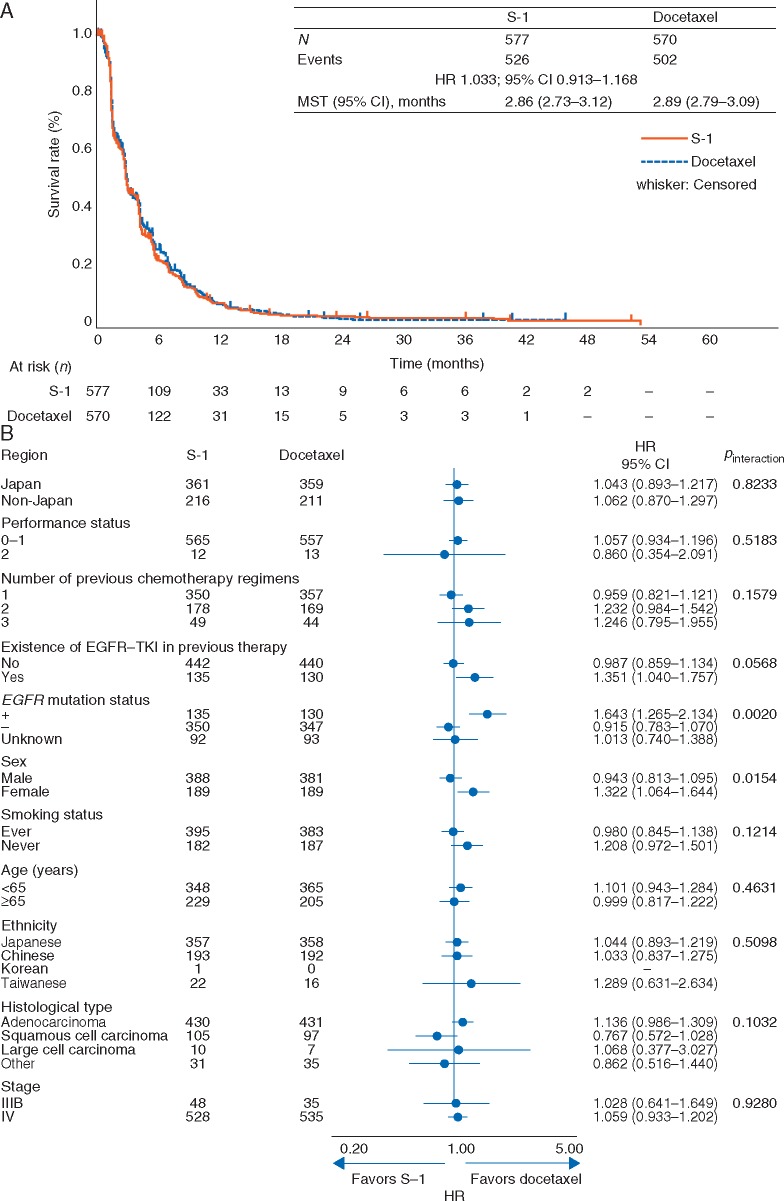

Kaplan–Meier curve and forest plot of PFS are shown in Figure 3. Median PFS was 2.86 and 2.89 months in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively (HR 1.033, 95% CI 0.913–1.168; P = 0.6080). In PFS subgroup analysis, interaction was observed in EGFR mutation status (P = 0.002) and sex (P = 0.0154) (Figure 3B), and was also observed in histological type (squamous/non-squamous, P = 0.024; data not shown).

Figure 3.

(A) Kaplan–Meier curve for progression-free survival (FAS); (B) Forest plot for progression-free survival. CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; FAS, full analysis set; HR, hazard ratio; MST, median survival time; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Median time to treatment failure was 2.66 and 2.56 months in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively (HR 0.886, 95% CI 0.788–0.997; P = 0.0436) (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Response rate was 8.3% in the S-1 arm and 9.9% in the docetaxel arm (P = 0.3761) (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Post-study treatment was given in 72.1% and 69.6% of patients in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively, and a subsequent EGFR-TKI was given in 27.6% and 28.8% of patients, respectively.

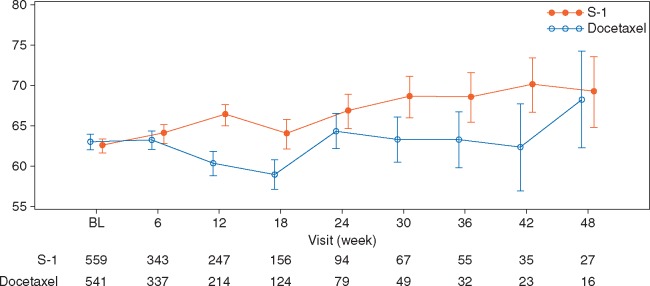

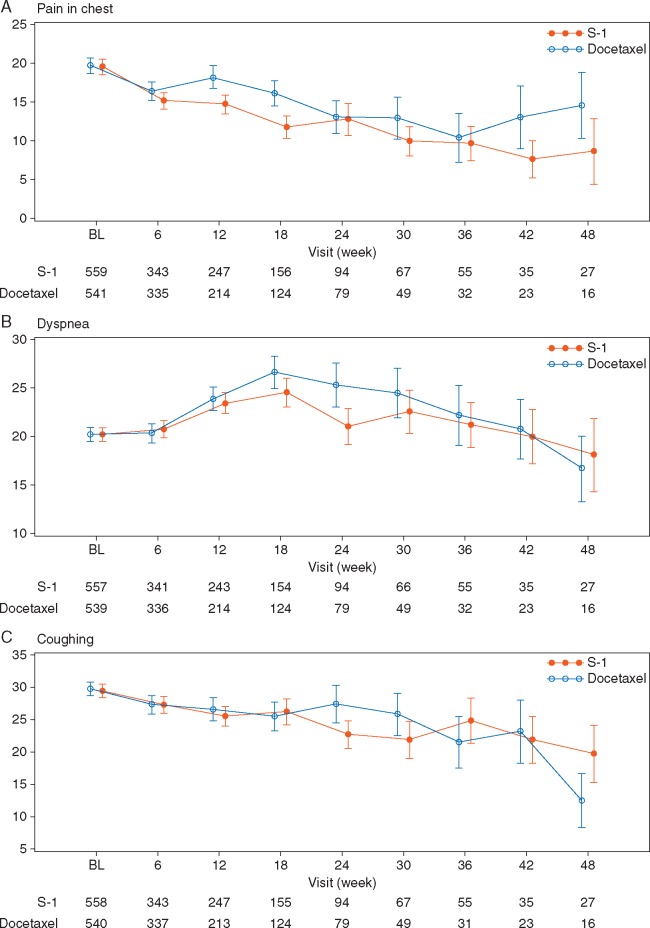

EORTC QLQ-C30 scores for global health status until 48 weeks were significantly better in the S-1 arm (P = 0.0065) with repeated-measures data (Figure 4). Additionally, QLQ-C30 scores for physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, and fatigue were significantly better in the S-1 arm. QLQ-LC13 scores for pain in chest, dyspnea, peripheral neuropathy, and alopecia were significantly better in the S-1 arm, while the dysphagia score was significantly better in the docetaxel arm (Figure 5; supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). QoL results by two docetaxel doses are shown in supplementary Figures S4−S6, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Figure 4.

Change in global health status item of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (FAS). BL, baseline; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer core quality of life questionnaire Core-30; FAS, full analysis set.

Figure 5.

Change in the EORTC QLQ-LC13 symptom scales from baseline (FAS) for (A) chest pain, (B) dyspnea, (C) coughing. BL, baseline; EORTC QLQ-LC13, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer core questionnaire lung cancer-specific module; FAS, full analysis set.

The most common adverse-drug reactions in the S-1 arm were decreased appetite (50.4%), nausea (36.4%), and diarrhea (35.9%), while those in the docetaxel arm were neutropenia (54.8%), leukocytopenia (43.9%), alopecia (46.6%), and decreased appetite (36.4%) (Table 2). AEs regardless to relationship to study drug and AEs by docetaxel dose are summarized in supplementary Tables S5 and S6, available at Annals of Oncology online, respectively.

Table 2.

Drug-related adverse events

| S-1 (n = 569) |

Docetaxel (n = 560) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | |||||

| Decreased appetite | 287 | (50.4) | 37 | (6.5) | 204 | (36.4) | 15 | (2.7) |

| Nausea | 207 | (36.4) | 5 | (0.9) | 149 | (26.6) | 8 | (1.4) |

| Diarrhea | 204 | (35.9) | 36 | (6.3) | 92 | (16.4) | 6 | (1.1) |

| Skin hyperpigmentation | 178 | (31.3) | 0 | (0) | 11 | (2.0) | 0 | (0) |

| Stomatitis | 133 | (23.4) | 14 | (2.5) | 80 | (14.3) | 5 | (0.9) |

| Vomiting | 106 | (18.6) | 9 | (1.6) | 64 | (11.4) | 4 | (0.7) |

| Malaise | 105 | (18.5) | 1 | (0.2) | 131 | (23.4) | 4 | (0.7) |

| Fatigue | 95 | (16.7) | 7 | (1.2) | 106 | (18.9) | 5 | (0.9) |

| Neutropenia | 85 | (14.9) | 31 | (5.4) | 307 | (54.8) | 267 | (47.7) |

| Constipation | 70 | (12.3) | 1 | (0.2) | 92 | (16.4) | 1 | (0.2) |

| Anemia | 69 | (12.1) | 15 | (2.6) | 53 | (9.5) | 8 | (1.4) |

| Weight decreased | 69 | (12.1) | 3 | (0.5) | 20 | (3.6) | 0 | (0) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 63 | (11.1) | 7 | (1.2) | 13 | (2.3) | 1 | (0.2) |

| Rash maculo-papular | 59 | (10.4) | 5 | (0.9) | 45 | (8.0) | 1 | (0.2) |

| Leukocytopenia | 54 | (9.5) | 7 | (1.2) | 246 | (43.9) | 163 | (29.1) |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 23 | (4.0) | 1 | (0.2) | 87 | (15.5) | 4 | (0.7) |

| Edema peripheral | 13 | (2.3) | 0 | (0) | 88 | (15.7) | 5 | (0.9) |

| Alopecia | 11 | (1.9) | 0 | (0) | 261 | (46.6) | 0 | (0) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 5 | (0.9) | 5 | (0.9) | 75 | (13.4) | 75 | (13.4) |

Data are n (%). Drug-related adverse events occurring in 10% or more of patients in either arm are shown. Treatment-related deaths were observed: disseminated intravascular coagulation and ileus in the docetaxel arm, hypovolemic shock in the S-1 arm.

Discussion

This is the first randomized, phase 3 study that confirms S-1 to be non-inferior in OS to docetaxel as second- or third-line therapy for patients with advanced NSCLC. Our findings were consistent across ethnicity, EGFR status, and histological type. S-1 was also as effective as docetaxel in terms of PFS and response rate. The magnitude of treatment effect and QoL was similar between the two doses of docetaxel (60 and 75 mg/m2). No differences were observed in subgroup analysis of OS, whereas in PFS subgroup analysis, interaction was observed in EGFR mutation status and sex, having longer PFS in the male subgroup or the EGFR wild-type subgroup with S-1 from docetaxel. Notably, EGFR mutation status and squamous cell carcinoma, which may play an important role in deciding the course of treatment for NSCLC patients, had an interaction with PFS but not with OS, suggesting that S-1 may have a better outcome in squamous cell carcinoma or EGFR wild-type status. For patients with EGFR mutation, the standard recommended treatment is osimertinib if there is presence of T790M mutation [8].

Significant differences were observed between the S-1 and docetaxel arms in about half of the items in QLQ-C30 and in QLQ-LC13; however, the clinical relevance of these findings will need to be addressed further in the context of mean differences. Items in the QLQ-C30 for global health status, social functioning, and financial difficulty favored S-1 with mean differences in the range of ‘small: subtle but nevertheless clinically relevant’ as defined by Cocks et al. [9]. No large benefits were observed in QLQ-LC13 items; some items reflected toxicity in each arm, with peripheral neuropathy and alopecia favoring S-1. In addition, there were no differences in gastrointestinal toxicity items (nausea, vomiting, appetite loss, and diarrhea) between arms, which could be an important factor in deciding treatment options for patients. Gastrointestinal toxicities can be well managed by supportive care. This might explain why QoL was better maintained with S-1 than with docetaxel and might serve as a rationale for using S-1.

The safety profiles of docetaxel and S-1 observed in this study were consistent with those of previous studies [4, 6]. Overall, incidence of AEs was similar between arms. Hematological AEs were more common in the docetaxel arm, whereas gastrointestinal AEs were more common in the S-1 arm. Incidence of febrile neutropenia was 0.9% and 13.6% in the S-1 and docetaxel arms, respectively; this factor may potentially affect treatment cost and hospitalization rates, although cost-effectiveness was not captured in the current study. Most gastrointestinal AEs reported in the S-1 arm were transient and manageable. The rate of drug discontinuation due to AEs was lower in the S-1 arm than in the docetaxel arm. Overall, S-1 was shown to produce an active response as a single agent for metastatic NSCLC with minimal toxicity. There were no differences in overall AEs between the two doses of docetaxel in the Japanese and non-Japanese populations. Of particular interest was our observation of a higher incidence of grade 3/4 neutropenia and febrile neutropenia in Japanese patients who received docetaxel at 60 mg/m2. This evidence is supportive of a lower dosage of docetaxel for this population.

Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy is now the new standard second-line therapy for patients who have failed first-line doublet chemotherapy [1−3], and addition of ramucirumab or nintedanib to docetaxel may also improve OS in selective patients [10, 11]. Key findings of these studies could not be taken into consideration in the design of the present study, thus forming a limitation of this study. We adopted docetaxel as the control arm when the drug was the only standard second-line therapy. On the other hand, not all patients are eligible or able to afford the novel but costly immunotherapies. Single-agent chemotherapy remains one of the options for this group of patients, and S-1 is an oral alternative to standard docetaxel.

In conclusion, S-1 shares similar efficacy with docetaxel but differs in toxicity and QoL profile. Our study confirmed S-1 as a viable treatment option for previously treated advanced NSCLC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients, their families, and the investigators who participated in the study, and members of the Data Monitoring Committee (Masahiro Fukuoka, Harubumi Kato, Nagahiro Saijo, Meilin Liao, and Masahiro Takeuchi). Dr SM had a role in the statistical analysis plan as trial statistician. The authors retained full control of the manuscript content, were involved at all stages of manuscript development, and approved the final version. Taiho Pharmaceutical of Beijing Co., Ltd. and TTY Biopharm Co., Ltd. assisted the study monitoring.

Funding

This work was sponsored by Taiho Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. Medical writing assistance was provided by Disha Dayal, PhD, and Shama Buch, PhD, of Cactus Communications, and funded by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. There is no applicable grant number.

Disclosure

HN received grants and personal fees from Taiho, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Ono, Eli Lilly, and Chugai; grants from Merck Serono, Pfizer, Eisai, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo, GSK, Yakult, Quintiles, and Astellas; and personal fees from Sanofi and Bristol-Myers Squibb. SL received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche Hutchison, MediPharma, GenomiCare, and Pfizer. TM received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Novartis, SFJ, Roche, MSD, Clovis Oncology, and BMS; personal fees from Genentech, Eli Lilly, Amgen, Janssen, GSK, PrIME Oncology, Merck Serono, BioMarin, ACEA Biosciences, Vertex, Aveo & Biodesix, Prime Oncology, OncoGenex Pharmaceutical, OncoGenex Technologies, PeerVoe, and geneDecode; and holds stock in Sanomics Limited. KN received grants from Oncotherapy Science, EPS Associates, Quintiles, and Japan Clinical Research Operations, and grants and personal fees from Taiho, Takeda, Eli Lilly, Eisai, MSD, Ono, Daiichi-Sankyo, Chugai, AstraZeneca, and Astellas. NY received grants and personal fees from Taiho. LZ received grants from AstraZeneca, BMS, and Pfizer. RS received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, and personal fees from Taiho, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and BMS. JCHY reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Roche/Genentech/Chugai, AstraZeneca, Astellas, MSD, Merck Serono, Pfizer, Novartis, Clovis Oncology, Celgene, Innopharma, and Merrimack. SS received personal fees from Chugai, Pfizer, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Taiho, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Ono. MN received grants from Novartis and Astellas, and grants and personal fees from Ono, Chugai, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Taiho, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca. TTak received grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly Japan, Chugai, and Ono; grants from Takeda and MSD; and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim Japan. KG received grants from MSD, Quintiles, GSK, OxOnc, Sumitomo Dainippon, Takeda, Astellas, Eisai, Amgen Astellas Biopharma, Merck Serono, AbbVie Stemcentrx, and Riken Genesis; grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Taiho, Chugai, BMS, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Ono, Pfizer, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Eli Lilly Japan, Novartis, and Daiichi-Sankyo; and personal fees from Yakult Honsha and Abbott Japan. YI received grants from Takeda Bio Development Center; grants and personal fees from Taiho and Chugai; and personal fees from Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Taisho Toyama, Pfizer, Ono, Eli Lilly, and Kaketsuken. SM received personal fees from Taiho. TTam received personal fees from Taiho, Chugai, Eisai, Yakult, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas, Novartis, Ono, and Daiichi-Sankyo. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW. et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD-L1-positive, advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-010): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L. et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1627–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D. et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389: 255–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R. et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 2095–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Di Maio M, Perrone F, Chiodini P. et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of docetaxel administered once every 3 weeks compared with once every week second-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 1377–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Totani Y, Saito Y, Hayashi M. et al. A phase II study of S-1 monotherapy as second-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009; 64: 1181–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rothmann M, Li N, Chen G. et al. Design and analysis of non-inferiority mortality trials in oncology. Stat Med 2003; 22: 239–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mok TS, Wu Y-L, Ahn M-J. et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 629–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cocks K, King MT, Velikova G. et al. Evidence-based guidelines for determination of sample size and interpretation of the European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O. et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 665–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reck M, Kaiser R, Mellemgaard A. et al. Docetaxel plus nintedanib versus docetaxel plus placebo in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (LUME-Lung 1): a phase 3, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.