Abstract

Background

Metastatic colorectal cancer frequently occurs in elderly patients. Bevacizumab in combination with front line chemotherapy (CT) is a standard treatment but some concern raised about tolerance of bevacizumab for these patients. The purpose of PRODIGE 20 was to evaluate tolerance and efficacy of bevacizumab according to specific end points in this population.

Patients and methods

Patients aged 75 years and over were randomly assigned to bevacizumab + CT (BEV) versus CT. LV5FU2, FOLFOX and FOLFIRI regimen were prescribed according to investigator’s choice. The composite co-primary end point, assessed 4 months after randomization, was based on efficacy (tumor control and absence of decrease of the Spitzer QoL index) and safety (absence of severe cardiovascular toxicities and unexpected hospitalization). For each arm, the treatment will be consider as inefficient if 20% or less of the patients met the efficacy criteria and not safe if 40% or less met the safety criteria.

Results

About 102 patients were randomized (51 BEV and 51 CT), median age was 80 years (range 75–91). Primary end point was met for efficacy in 50% and 58% and for safety in 61% and 71% of patients in BEV and CT, respectively. Median progression-free survival was 9.7 months in BEV and 7.8 months in CT. Median overall survival was 21.7 months in BEV and 19.8 months in CT. The 36-month overall survival rate was 27% in BEV and 10.1% in CT. Severe toxicities grade 3/4 were mainly non-hematologic toxicities (80.4% in BEV, 63.3% in CT).

Conclusion

Bevacizumab combined with CT was safe and efficient. Both arms met the primary safety and efficacy criteria.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, elderly, antiangiogenic, randomized trial, composite criteria

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) occurs mainly in elderly patients. Recent European evaluation reported that 38.5% of CRC patients were >75 [1]. Several concerns have risen about the care of elderly due to the age-related comorbidities and functional status [2]. Moreover, elderly patients are underrepresented in clinical trials, thus the transposition for elderly of current guidelines established in younger patients should be taken with caution [3, 4].

In first-line metastatic CRC (mCRC), bevacizumab combined with irinotecan has demonstrated an overall survival (OS) advantage compare with irinotecan based chemotherapy (CT) alone [5] and an improvement of progression-free survival (PFS) in combination with 5-fluorouracil (FU) compare with single FU regimen in patients considered unfit for a doublet CT regimen [6].

Two recent phase III trials comparing capecitabine alone or combined with bevacizumab have focused on elderly patients. Both studies reported a PFS improvement in the bevacizumab arm [7, 8] without significant OS improvement. Some concerns also raised for the use of usual oncologic end points as OS and PFS in elderly patients [9]. It has been reported that if elderly patients have a good acceptance of CT they are less willing to have a toxicity than their younger counterparts [10]. Moreover, unplanned hospitalization is a concern in elderly patients as it can delay scheduled treatment and result in functional decline [11]. A recent guideline of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) recommends to the use of composite end point evaluating quality of life (QoL) and global toxicity for mCRC trials in elderly [12]. According to these recommendations we built specifically for PRODIGE 20 trial a composite end point assessing efficacy (tumor control rate and QoL evaluation) and safety (unexpected hospitalization and severe cardiovascular toxicity).

Several studies have demonstrated that doublet CT have a limited effect on PFS and did not prolong OS compare with fluoropyrimidine alone in elderly patients [13, 14]. Nevertheless, the SIOG guideline recommends doublet CT in fit elderly patients [12]. Thus, it is important to allow CT choice according to investigator evaluation.

Patients and methods

Patient selection

The eligibility criteria were histologically confirmed unresectable mCRC, age ≥ 75 years, ECOG ≤2, ≥ 1 measurable lesion according RECIST 1.1, no previous CT for metastatic disease, adjuvant therapy if stopped at least 6 months before randomization, and geriatric questionaries’ fulfilled. Uneligibility criteria were symptomatic bowel obstruction, brain metastasis, other malignant tumor, surgery in the previous 4 weeks, neutrophils <1500/mm3, platelets <100 000/mm3 or proteinuria >1 g/24 h, wound or gastric ulcer and following disease during the last 12 months previous randomization: uncontrolled hypertension, myocardial infarction, cardiac insufficiency, stroke, arterial ischemia grade > 2, pulmonary embolism. Written informed consent was obtained for each patient. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee (CPP EST I DIJON n°100109 in 26 January 2010) and registered in clinicaltrials.gov with the number NCT01900717.

Study design

This phase II trial was a randomized non-comparative phase II study evaluating bevacizumab combined with CT (BEV) and CT alone (CT) in patients with mCRC aged 75 years or more. The CT regimen was chosen by the investigators before randomization according to their clinical evaluation. The following regimens were authorized: simplified LV5FU2, modified FOLFOX6 and modified FOLFIRI [13] (supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online). Randomization was stratified according to CT (FU monotherapy versus doublet), primary tumor (resection versus no resection), Spitzer QoL (0–3 versus 4–7 versus 8–10) [15]. The recommended treatment duration was a minimum of 6 months, but investigators could to decide to continue the treatment until progression. All toxicities were graded according to the US National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (version 4.0). Serious adverse events were also reported. Radiological assessments were carried out every 8 weeks (abdominal and thoracic CT scan or MRI) and tumor response was evaluated according to RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) criteria (version 1.1). An ancillary geriatric study was planned. Statistical analyses are described in supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Primary end point and sample size

This trial was designed to evaluate a composite co-criterion assessed 4 months after randomization and based on efficacy co-criterion: tumor control (stable disease or objective response) and no decrease ≥ 2 points of the Spitzer QoL index; and safety co-criterion: absence of severe cardiovascular toxicities defined by arterial hypertension grade 4 or thromboembolic event grade 3–4 or cardiac insufficiency grade 3–4 or an unexpected hospitalization whatever the cause at the exception of CT administration. To demonstrate an efficacy co-criterion for >20% of the patients (40% expected) and a safety co-criterion for >40% of the patients (70% expected), 92 assessable patients was needed (one-sided alpha = 5%, power = 90%). All patients with an mCRC, receiving at least one dose of treatment and with at least one efficacy assessment and one Spitzer evaluation after treatment, were considered assessable and included in the modified intent-to-treat population (mITT). Assuming for 10% non-assessable patients, 102 patients were randomized in the trial. The decision rules applied only for BEV arm were: if ≥ 15 patients met the efficacy co-criterion and if ≥ 25 patients met the safety co-criterion, the treatment was considered efficient and well-tolerated.

Secondary end points

Secondary end points were objective tumor response rate (ORR), PFS, OS, and tolerance. ORR was defined as complete or partial response. PFS was defined as the time from randomization to first progression or death (all causes). Patients alive without progression were censored at the last follow-up. OS was defined as the time between randomization and death (all causes). Toxicity was reported by the maximum toxicity grade per patient and per toxicity term during the treatment.

Results

Baseline characteristics

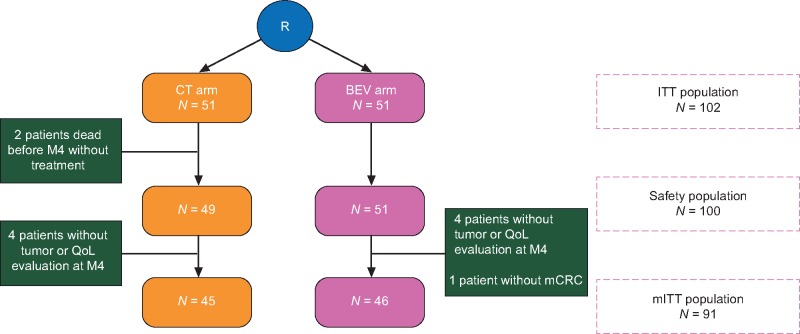

Between July 2011 and July 2013, 51 patients were randomly assigned to CT and 51 to BEV (Figure 1). The median follow-up was of 20.4 (Q1–Q3: 11.8–31.2) months. Two patients died without receiving any treatment in CT. Four patients did not have tumor or QoL evaluation at M4 in each arm and one patient was enrolled without documented mCRC in BEV. Thus, the mITT population for the primary end point was 45 patients in CT and 46 in BEV. The two groups were well-balanced with regards to baseline characteristics except for the choice of doublet as there is more FOLFOX in CT and FOLFIRI in BEV (Table 1). The median age was 80 years (range 75–90). RAS status was not determined upfront before enrollment.

Figure 1.

Flow chart (CONSORT diagram).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristics | CT | BEV |

|---|---|---|

| N = 51 | N = 51 | |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median (min–max) | 80.1 (75.0–90.6) | 80.9 (75.2–88.3) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 30 (58.8%) | 26 (51.0%) |

| Female | 21 (41.2%) | 25 (49.0%) |

| Primary localization | ||

| Right colon | 19 (37.3%) | 16 (31.4%) |

| Left colon | 18 (35.3%) | 21 (41.2%) |

| Rectum | 14 (27.5%) | 14 (27.5%) |

| Primary tumor resected | ||

| Yes | 30 (58.8%) | 31 (60.8%) |

| No | 21 (41.2%) | 20 (39.2%) |

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||

| LV5FU2 | 26 (51.0%) | 26 (51.0%) |

| FOLFOX | 14 (27.5%) | 9 (17.6%) |

| FOLFIRI | 9 (17.6%) | 16 (31.4%) |

| Not treated | 2 (3.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | n = 50 | |

| <21 | 8 (16.0%) | 9 (17.6%) |

| ≥21 | 42 (84.0%) | 42 (82.4%) |

| Spitzer QoL | ||

| 0–7 | 16 (31.4%) | 15 (29.4%) |

| 8–10 | 35 (68.6%) | 36 (70.6%) |

| Biologics parameters | ||

| Alkaline phosphatases | n = 48 | |

| ≤2 LN | 37 (77.1%) | 42 (82.3%) |

| >2 LN | 11 (22.9%) | 9 (17.7%) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | ||

| <10 (female), <11 (male) | 11 (21.6%) | 5 (9.8%) |

| ≥10 (female), ≥11 (male) | 40 (78.4%) | 46 (90.2%) |

| Albumin | n = 43 | n = 49 |

| ≤35 g/l | 20 (46.5%) | 17 (34.7%) |

| >35 g/l | 23 (53.5%) | 32 (65.3%) |

| Creatinine clearance | n = 48 | n = 50 |

| >45 ml/min | 37 (77.1%) | 36 (72.0%) |

| ≤45 ml/min | 11 (22.9%) | 14 (28.0%) |

| CEA | n = 49 | n = 47 |

| ≤2 LN | 35 (71.4%) | 40 (85.1%) |

| >2 LN | 14 (28.6%) | 7 (14.9%) |

| CA 19-9 | n = 47 | n = 48 |

| ≤2 LN | 19 (40.4%) | 29 (60.4%) |

| >2 LN | 28 (59.6%) | 19 (39.6%) |

LN, limit of normal; BMI, body mass index; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Treatment administration

The median duration of the treatment was 6.0 months (Q1–Q3: 3.3–9.9) in CT and 7.7 months (Q1–Q3: 3.7–20.3) in BEV. CT was given for a median number of 12 cycles (Q1–Q3: 8–18) in CT and 16 cycles (Q1–Q3: 7–29) in BEV. All patients have stopped the study treatment at time of evaluation. At least one CT dose reduction was observed for 57.1% patients in CT and 70.6% patients in BEV. A dose reduction was observed in CT for 38% patients treated with FU and for 78% patients treated with doublet and in BEV for 65% patients treated with FU and for 76% patients treated with doublet. Two-third of doses for all the CT component was administered in 75.5% patients in CT and 66.7% patients in BEV during the first 4 months of treatment. FU bolus was the product mainly interrupted. Treatment interruption was mainly due to disease progression in both arms (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Primary composite co-criterion

According to the decisions rules, both efficacy and safety objectives for BEV were reached: 23 patients met the efficacy co-criterion (50.0% [90% CI: 37.1–62.9]) and 28 patients met the safety co-criterion (60.9% [90% CI: 47.7–73.0]). BEV arm was considered efficient and well-tolerated (Table 2). A trend of a better tumor control in BEV arm but more QoL degradation, more unexpected hospitalization and more grade 3–4 cardiovascular toxicity is observed. An exploratory analysis did not found differences for composite criterion according the type of doublet regimen (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Indeed, there is small number on each group and no definitive conclusion could be drawn.

Table 2.

Primary end point assessed 4 months after randomization

| Primary end point | CT | BEV |

|---|---|---|

| N = 45 | N = 46 | |

| Tumor controlled | 33 (73.3%) | 36 (78.3%) |

| No QoL degradation >2 | 29 (64.4%) | 27 (58.7%) |

| Efficacy co-criterion reached | 26 (57.8%) | 23 (50.0%) |

| No unexpected hospitalization | 32 (71.1%) | 30 (65.2%) |

| No grade 3–4 cardiovascular toxicity | 41 (91.1%) | 40 (87.0%) |

| Safety co-criterion reached | 32 (71.1%) | 28 (60.9%) |

| Both efficacy and safety end point reached | 21 (46.7%) | 16 (34.8%) |

Response rate, PFS and OS

The following data are indicative as PRODIGE 20 trial was not designed to compare the differences in efficacy between the two arms. The best ORR was 37.2% in BEV and 32.6% in CT (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

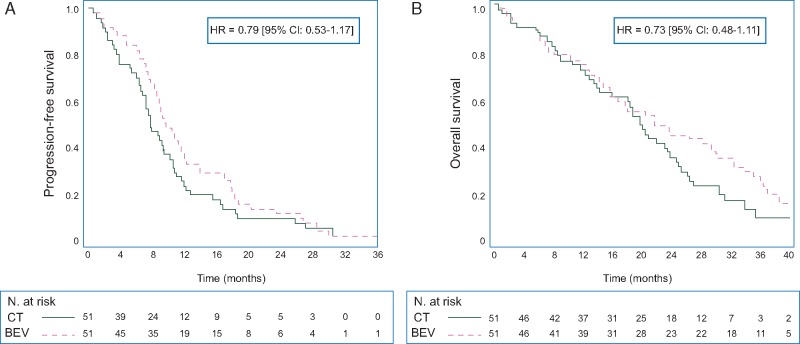

About 49 (96.1%) patients in CT and 50 (98.0%) patients in BEV have progressed or died. The median PFS was 7.8 months [95% CI: 6.6–10.2] in CT and 9.7 months [95% CI: 8.2–12.0] in BEV (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.53–1.17) (Figure 2A). The 12-month PFS rate was 23.5% [95% CI: 13.0–35.8] in CT and 37.3% [95% CI: 24.3–50.2] in BEV.

Figure 2.

(A) Kaplan–Meier estimate of progression-free survival. (B) Kaplan–Meier estimate of overall survival.

About 45 (88.2%) patients in CT and 44 (86.3%) patients in BEV have died. Median OS was 19.8 months [95% CI: 13.9–23.7] in CT and 21.7 months [95% CI: 14.8–30.3] in BEV (HR 0.73, 95% CI: 0.48–1.11; Figure 2B). The 36-month OS rate was 10.1% [95% CI: 3.1–22.0] in CT and 27.0% [95% CI: 15.7–39.7] in BEV.

Prediction of PFS and OS by both and combined composite co-criterion

An exploratory analysis was carried out to assess the predictive value of both and combined composite co-criterion for PFS and OS (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). Efficacy, safety and combined composite co-criterion were associated with PFS and OS.

Tolerance

The main severe adverse events (grade 3–4) in CT and BEV arm were, respectively, neutropenia (12.2% versus 11.8%), diarrhea (10.2% versus 9.8%), and thromboembolic events (6.1% versus 9.8%). As expected with bevacizumab, grade 3–4 arterial hypertension was more important in the BEV arm (13.7% versus 6.1%) (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Second and further lines of CT

Second-line CT was given in 31 (61%) patients in CT and 25 (49%) in BEV (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online). A targeted therapy was given to 21 (41%) patients in CT and 13 (25%) patients in BEV. Third-line treatment was started for 16 (31%) patients in CT and for 8 (16%) in BEV. Altogether, a targeted therapy was given at least in one line across all treatment lines in 26 (51%) patients in CT. Only one patient had surgery of metastases in BEV. A second-line CT was given in 45% and 55% of the patients treated by FU or doublet, respectively.

Discussion

This randomized study was the first one evaluating bevacizumab treatment in mCRC patients aged of 75 years or more according to geriatric guidelines. Our results showed that the addition of bevacizumab to CT was safe and efficient. This randomized phase II study was non-comparative so not designed to demonstrate any difference or superiority of BEV arm over the CT arm for primary or secondary end points.

The efficacy co-criterion assessed 4 months after the randomization was reached in BEV. The separate analysis of the two efficacy criteria considered showed that the tumor control rate was higher in BEV arm but the QoL was less deteriorated in the CT arm. The trend observed in favor of CT for QoL could be explained by the slight difference existing in term of safety meaning that QoL and toxicities are correlated. The time to QoL degradation was similar in both arms [16].

Concerning the safety part, the majority of the patients had no unexpected hospitalization and there is few severe cardiovascular toxicity in both arms during the first 4 months. Considering all toxicities during the treatment duration there is an increased of arterial hypertension and a 3.7% difference for thrombolytic events as expected with bevacizumab. This is in-line with what it was observed in previous study in elderly [7, 17]. A careful monitoring of antihypertensive treatment is needed in elderly treated with bevacizumab.

Composite co-criterion assessing both tumor control, QoL and tolerance remains exploratory. The tumor control rate was in the same range for CT that those observed in our previous trial comparing 5-fluorouracil monotherapy to FOLFIRI [13]. The prognostic value of Spitzer QoL score have been validate in oncology setting [18]. Because of the lack of previous prospective data about the evolution of Spitzer QoL score under treatment in elderly patient treated for mCRC the hypothesis used in our trial design was exploratory. The optimal time of evaluation is also questionable as treatments are both well-tolerated. Unfortunately, QoL evaluations are exposed to a high drop-out rate. Around 10% of the patients in our study did not have an evaluation at 4 months and this rate increased afterward. Indeed, an intensive monitoring and investigators training is mandatory if QoL is part of primary end point. The safety co-criterion appears as poorly discriminant between both arms. Nevertheless, both criteria are predictive for PFS and OS but this observation is obtain on small number. It must be point out that our criteria was built specially to evaluate antiangiogenic toxicity and could not be used for other purpose. Further research for optimal composite criteria is needed in geriatric oncology.

Our PFS results are in favor of BEV but are of less magnitude compared with the results of the two previous studies that have compared bevacizumab plus capecitabine with capecitabine monotherapy (HR= 0.53 [7] and 0.52 [8]). It must be pointed out that the median age was 80 years in our study but 76 [7] and 78 [8] in the previous studies. Others studies already suggested that the benefit for PFS of treatment intensification was mainly observed in patients of 70–80 rather than >80 [19, 20].

None previous study demonstrated a significant OS benefit of bevacizumab combined with CT compared with CT alone in elderly patients. Our OS results are consistent with previous observations in phase III randomized study that have addressed elderly patients [7, 8].

It must be pointed out that there is a trend in favor of BEV for usual end point as PFS and OS. At the contrary, QoL, unexpected hospitalization, cardiovascular toxicity and in result the primary safety co-criterion seems to be in favor of CT. This observation suggests that bevacizumab was associated with more toxicity even mild but is worthwhile given the longer PFS and OS.

We evaluated bevacizumab both in combination with FU monotherapy or with doublet CT which was never evaluated in previous randomized studies [7, 8]. The investigators were allowed to choose between monotherapy or doublet according their evaluation of the patient. This pragmatic design minimizes patient selection to enter the trial. Moreover, ∼50% of patients received FU monotherapy or doublet, this proportion is close to those observed in a national cohort of elderly patient treated in front line for mCRC in France [21]. Nevertheless, we could not rule out a part of patient selection for enter in a clinical trial. In our study, the effect of bevacizumab was similar whatever the doublet regimen delivered. It must be point out that doublet CT was not associated with an increase of PFS or OS in subgroup analyses that raise the question of the need for doublet therapy in front line [16]. Nevertheless, our results confirm the possibility to combine bevacizumab with several CT regimens in elderly patients.

In our study, we observed a prolonged median duration of exposure to treatment despite advanced age. This could be explained by the pragmatic design of the trial that allow a tailored CT according to the investigator evaluation of the patient. Alternatively we cannot rule out a more stringent patient selection than in the previous trial that have evaluated bevacizumab in elderly [7, 8]. Moreover, 55% of patients received a second-line therapy compared with 37% in the AVEX trial [7] and 10% in AGITG MAX trial [8]. This high proportion of second-line treatment especially in the CT group could explain that the OS are close in both groups. It must be pointed out that >40% of patients were treated with a targeted therapy in second line in CT versus 25% in BEV.

In conclusion, bevacizumab in combination with both 5-fluorouracil monotherapy or doublet CT is well-tolerated and efficient in selected elderly patients. A trend for a longer tumor control is observed in BEV compare with CT. A phase III trial with end point adapted to geriatric population would be of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the operational team (statisticians, data manager and CRAs), with K. Le Malicot, F. Bonnetain† P. Carni, C. Choine, F. Guiliani, N. Lasmi, G. Arnould, N. Guiet, M. Maury-Negre, H. Fattouh, N. Le Provost, J. Bez, and C. Girault for the editing support and Ligue contre le cancer, Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique (Institut National de Cancérologie) and Roche France for the financial support.

Funding

Grant Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique No. PHRC10_07-01 (Institut National de Cancérologie et CHU de Dijon); Grant No. ML-23006 from Roche.

Disclosure

TA: Sanofi/Roche/Pfizer/Ipsen/Pierre Fabre/Novartis;

OB: Novartis/Lilly/Bayer/Pierre Fabre/Roche/Merck/Amgen/Boehringer Ingelheim;

JT: Roche/Merck/Amgen/Sanofi/Lilly/Celgene/Baxalta Servier;

SK: Amgen;

PLE: Sanofi/Merck/Roche/Ipsen Pharma/BMS/Novartis/Amgen;

RF: Merck Serono/Amgen;

FKA: Roche/Sanofi/Bayer;

CL: Novartis/Ipsen/Roche/Celgene/Amgen/Sanofi;

TL: Amgen/Sanofi/Lilly;

SL-D: Iceram/Medincell;

FR: Gilead/Teva; and

EF: Roche/Merck/Sanofi. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Appendix for a list of the FFCD Investigators/collaborators:

Mohamed-Ayman Zawadi (Centre Hospitalier Les Oudairies, La Roche sur Yon); Julien Volet (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Reims, Hôpital Robert Debré, Reims); Gérard Cavaglione (Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice); Céline Lepere (APHP, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris); Philippe Rougier (APHP, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris); Aziz Zaanan (APHP, Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou, Paris); Dominique Besson (Centre CARIO HPCA, Plerin); Kara Slimane Fawzi (Centre Hospitalier Saint Jean, Perpignan); Antoine Adenis (Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille); Gilles Gatineau-Sailliant (Centre Hospitalier, Meaux); Catherine Brezault (APHP, Hôpital Cochin, Paris); Romain Coriat (APHP, Hôpital Cochin, Paris); David Tougeron (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Poitiers, Hôpital de la Milétrie, Poitiers); Vincent Hautefeuille (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire, Amiens); Laurence Chone (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Nancy – Brabois, Vandoeuvre Les Nancy); Yann Molin (Clinique La Sauvegarde, Lyon); Jean-François Seitz (APHM, Hôpital La Timone, Marseille); Véronique Jestin Le Tallec (Centre Hospitalier Régional et Universitaire, Brest); Meher Ben Abdelghani (Centre Paul Strauss, Strasbourg); Anne-Laure Villing (Centre Hospitalier, Auxerre); Amar Aouakli (Centre Hospitalier Général Arrondissement Montreuil, Rang-du-Fliers); Virginie Sebbagh (Centre Hospitalier, Compiègne); Ahmed Bedjaoui (Hôpitaux du Léman, Thonon Les Bains); Emmanuel Mitry (Institut Curie, Saint Cloud); Elisabeth Carola (Centre Hospitalier, Senlis); Olivier Boulat (Hôpital Henri Duffaut, Avignon); Anne-Marie Queuniet (Centre Hospitalier, Elbeuf); Olivier Capitain (Centre Paul Papin, Angers); Jean-Louis Jouve (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Le Bocage, Dijon); Isabelle Baumgaertner (Hôpital Henri Mondor, Créteil); Françoise Almaric, (Clinique Clairval, Marseille); Franck Bonnetain (Unité de méthodologie et de qualité de vie, université de l’hôpital de Besançon, Besançon) ; Fabien Subtil (Hospices civils de Lyon, Université Lyon 1, Lyon).

References

- 1. Holleczek B, Rossi S, Domenic A. et al. On-going improvement and persistent differences in the survival for patients with colon and rectum cancer across Europe 1999-2. Eur J Cancer 2015; 51: 2158–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aparicio T, Pamoukdjian F, Quero L. et al. Colorectal cancer care in elderly patients: unsolved issues. Dig Liver Dis 2016; 48: 1112–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frerot M, Jooste V, Binquet C. et al. Factors influencing inclusion in digestive cancer clinical trials: a population-based study. Dig Liver Dis 2015; 47: 891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sorbye H, Pfeiffer P, Cavalli BN. et al. Clinical trial enrollment, patient characteristics, and survival differences in prospectively registered metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer 2009; 115: 4679–4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W. et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2335–2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kabbinavar FF, Schulz J, McCleod M. et al. Addition of bevacizumab to bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 3697–3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cunningham D, Lang I, Marcuello E. et al. Bevacizumab plus capecitabine versus capecitabine alone in elderly patients with previously untreated metastatic colorectal cancer (AVEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Price TJ, Zannino D, Wilson K. et al. Bevacizumab is equally effective and no more toxic in elderly patients with advanced colorectal cancer: a subgroup analysis from the AGITG MAX trial: an international randomised controlled trial of capecitabine, bevacizumab and mitomycin C. Ann Oncol 2012; 23: 1531–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Bekkum ML, van Munster BC, Thunnissen PL. et al. Current palliative chemotherapy trials in the elderly neglect patient-centred outcome measures. J Geriatr Oncol 2015; 6: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT.. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 1994; 86: 1766–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Manzano JG, Luo R, Elting LS. et al. Patterns and predictors of unplanned hospitalization in a population-based cohort of elderly patients with GI cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(31): 3527–3533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papamichael D, Audisio RA, Glimelius B. et al. Treatment of colorectal cancer in older patients: International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) consensus recommendations 2013. Ann Oncol 2015; 26: 463–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aparicio T, Lavau-Denes S, Phelip JM. et al. Randomized phase III trial in elderly patients comparing LV5FU2 with or without irinotecan for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer (FFCD 2001-02). Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seymour MT, Thompson LC, Wasan HS. et al. Chemotherapy options in elderly and frail patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MRC FOCUS2): an open-label, randomised factorial trial. Lancet 2011; 377: 1749–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spitzer WO, Dobson AJ, Hall J. et al. Measuring the quality of life of cancer patients: a concise QL-index for use by physicians. J Chronic Dis 1981; 34: 585–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Aparicio T, Francois E. et al. Prognostic factor analysis for elderly patients treated for metastatic colorectal cancer in the randomized phase II trial PRODIGE 20. Ann Oncol ESMO 2016. 2016; 27: 583P. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kozloff M, Yood MU, Berlin J. et al. Clinical outcomes associated with bevacizumab-containing treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: the BRiTE observational cohort study. Oncologist 2009; 14: 862–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coates A, Thomson D, McLeod GR. et al. Prognostic value of quality of life scores in a trial of chemotherapy with or without interferon in patients with metastatic malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer 1993; 29A(12): 1731–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aparicio T, Gargot D, Teillet L. et al. Geriatric factors analyses from FFCD 2001-02 phase III study of first-line chemotherapy for elderly metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 2016; 74: 98–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Folprecht G, Seymour MT, Saltz L. et al. Irinotecan/fluorouracil combination in first-line therapy of older and younger patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: combined analysis of 2,691 patients in randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 1443–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Doat S, Thiebaut A, Samson S. et al. Elderly patients with colorectal cancer: treatment modalities and survival in France. National data from the ThInDiT cohort study. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50: 1276–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.