Abstract

Background

The BRIM-3 trial showed improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) for vemurafenib compared with dacarbazine in treatment-naive patients with BRAFV600 mutation–positive metastatic melanoma. We present final OS data from BRIM-3.

Patients and methods

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive vemurafenib (960 mg twice daily) or dacarbazine (1000 mg/m2 every 3 weeks). OS and PFS were co-primary end points. OS was assessed in the intention-to-treat population, with and without censoring of data for dacarbazine patients who crossed over to vemurafenib.

Results

Between 4 January 2010 and 16 December 2010, a total of 675 patients were randomized to vemurafenib (n = 337) or dacarbazine (n = 338, of whom 84 crossed over to vemurafenib). At the time of database lock (14 August 2015), median OS, censored at crossover, was significantly longer for vemurafenib than for dacarbazine {13.6 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 12.0–15.4] versus 9.7 months [95% CI 7.9–12.8; hazard ratio (HR) 0.81 [95% CI 0.67–0.98]; P = 0.03}, as was median OS without censoring at crossover [13.6 months (95% CI 12.0–15.4) versus 10.3 months (95% CI 9.1–12.8); HR 0.81 (95% CI 0.68–0.96); P = 0.01]. Kaplan–Meier estimates of OS rates for vemurafenib versus dacarbazine were 56% versus 46%, 30% versus 24%, 21% versus 19% and 17% versus 16% at 1, 2, 3 and 4 years, respectively. Overall, 173 of the 338 patients (51%) in the dacarbazine arm and 175 of the 337 (52%) of those in the vemurafenib arm received subsequent anticancer therapies, most commonly ipilimumab. Safety data were consistent with the primary analysis.

Conclusions

Vemurafenib continues to be associated with improved median OS in the BRIM-3 trial after extended follow-up. OS curves converged after ≈3 years, likely as a result of crossover from dacarbazine to vemurafenib and receipt of subsequent anticancer therapies.

ClinicalTrials.gov

Keywords: melanoma, BRAF mutation, vemurafenib, dacarbazine

Introduction

Several new treatment options for metastatic melanoma have emerged over the last 5 years, including small-molecule inhibitors of BRAF and MEK and monoclonal antibodies targeting programmed death (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) [1–12]. These agents have revolutionized the treatment of metastatic melanoma, but limited data are available so far regarding long-term outcomes.

Activating mutations in the BRAF oncogene are the most frequent genetic alterations in melanoma, occurring in ≈50% of melanomas [13–16]. BRAF mutations result in constitutive activation of the BRAF kinase and, consequently, downstream activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling pathway that regulates cell proliferation, growth and differentiation [13, 16].

Vemurafenib is an inhibitor of oncogenic BRAF kinase and was the first BRAF inhibitor to be tested in a phase III trial. The pivotal BRIM-3 study was a randomized phase III study that compared vemurafenib with dacarbazine in patients with previously untreated unresectable stage IIIC or stage IV melanoma harbouring BRAFV600 mutations [1, 17]. The prespecified interim analysis of the BRIM-3 study (data cut-off date, 30 December 2010) demonstrated improved median progression-free survival [PFS; hazard ratio (HR) 0.26; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.20–0.33; P < 0.001] and overall survival (OS; HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.26–0.55; P < 0.001) for vemurafenib compared with dacarbazine [1]. After extended follow-up (data cut-off date, 1 February 2012), vemurafenib remained associated with improved PFS (HR 0.38; 95% CI 0.32–0.46; P < 0.001) and OS (HR 0.70; 95% CI 0.57–0.87; P < 0.001) compared with dacarbazine [17]. Previously, we reported landmark OS analysis at 1 year. Here, we report final OS data from the BRIM-3 study, including landmark analyses at 3 and 4 years (database lock 14 August 2015).

Patients and methods

Study design

The BRIM-3 study was a multicentre, randomized, open-label, parallel-arm study. Detailed methods for the BRIM-3 study have previously been reported [1, 17]. Briefly, eligible patients were age ≥18 years, had previously untreated, unresectable stage IIIC or stage IV melanoma with a BRAFV600 mutation, life expectancy ≥3 months, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0 or 1 and adequate haematological, hepatic and renal function.

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either vemurafenib (960 mg orally twice daily) or dacarbazine (1000 mg/m2 as an intravenous infusion every 3 weeks). Randomization was stratified according to American Joint Committee on Cancer stage (IIIC, M1a, M1b or M1c), ECOG PS (0 or 1), geographic region (North America, Western Europe, Australia/New Zealand or other region) and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (normal or elevated). Treatment was administered until disease progression.

The protocol was approved by institutional review boards at each participating institution and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent.

Outcomes

The co-primary end points were OS, defined as the time from randomisation to death from any cause, and PFS, defined as the time from randomisation to documented disease progression or death. Secondary end points included confirmed response according to Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors, version 1.1, time to response, duration of response and safety and tolerability. Final OS results and long-term safety and tolerability are reported; PFS and secondary end points have been reported elsewhere [1, 17].

Statistical analysis

Enrolment of 680 patients would provide power of 80% to detect an HR of 0.65 for OS with an α level of 0.045 and a power of 90% to detect an HR of 0.55 for PFS with an α level of 0.005. The final OS analysis was planned after 196 deaths had occurred.

A planned interim analysis of OS occurred on 14 January 2011 [1]. The data safety monitoring board recommended release of the results due to compelling efficacy and recommended that patients in the dacarbazine arm be allowed to cross over to vemurafenib. The protocol was amended to allow crossover on 14 January 2011; disease progression on dacarbazine was not required in order for patients to cross over to vemurafenib.

The database lock date for the final OS analysis was 14 August 2015. OS was assessed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population, with and without censoring of data for patients in the dacarbazine arm who crossed over to vemurafenib. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Sensitivity analyses were also carried out using five scenarios of assumed benefit for vemurafenib after crossover (reduction in the risk for death by 20%, 30%, 40%, 50% or 60%). For each scenario, survival after crossover was imputed to be the observed survival after crossover reduced by the assumed benefit in survival attributable to vemurafenib after crossover.

The ITT population included all randomly assigned patients and the safety population included all patients who received a study drug. Prespecified subgroup analyses were carried out according to age, sex, ECOG PS, tumour stage, LDH level at baseline and geographic region.

Results

Patients

Between 4 January 2010 and 16 December 2010, 675 eligible patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to receive vemurafenib (n = 337) or dacarbazine (n = 338). As previously reported [1, 17], baseline characteristics were well balanced between treatment arms (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | Dacarbazine (n=338) | Vemurafenib (n=337) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 52 (17–86) | 56 (21–86) |

| Male | 181 (54) | 200 (59) |

| White race | 338 (100) | 333 (99) |

| Geographic region | ||

| Australia/New Zealand | 38 (11) | 39 (12) |

| North America | 86 (25) | 86 (26) |

| Western Europe | 203 (60) | 205 (61) |

| Other | 11 (3) | 7 (2) |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0 | 230 (68) | 229 (68) |

| 1 | 108 (32) | 108 (32) |

| LDH level | ||

| Normal (≤ULN) | 142 (42) | 142 (42) |

| Elevated (>ULN) | 196 (58) | 195 (58) |

| Disease stage | ||

| Unresectable IIIC | 13 (4) | 20 (6) |

| M1a | 40 (12) | 34 (10) |

| M1b | 65 (19) | 62 (18) |

| M1c | 220 (65) | 221 (66) |

Reproduced with permission from Chapman PB et al. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2507–2516, Copyright Massachusetts Medical Society.

Unless otherwise indicated, all data are n (%).

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal.

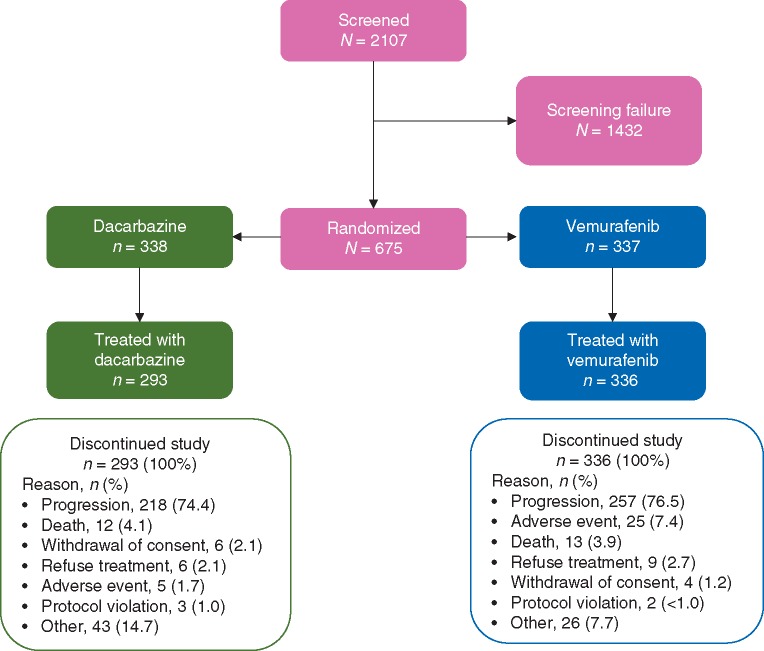

At the time of database lock (14 August 2015), all patients in both treatment arms had discontinued from the study, primarily because of disease progression (Figure 1). The median duration of follow-up for the ITT population was 13.4 months (range 0.4–59.6) for patients in the vemurafenib arm and 9.2 months (range 0–56.2) for patients in the dacarbazine arm. Among 66 patients in the vemurafenib arm and 79 patients in the dacarbazine arm who were known not to have died at the time of database lock, the median follow-up duration was 49.9 months (range 0.4–59.6) and 42.8 months (range 0–56.2), respectively.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

A total of 84 of 338 patients in the dacarbazine arm crossed over to vemurafenib treatment. The median duration of vemurafenib exposure was similar between patients initially randomized to receive vemurafenib (median 6.6 months; range 0–57.1) and those who crossed over from dacarbazine (median 6.6 months; range 0.7–47.3). Overall, 173 of the 338 patients (51%) in the dacarbazine arm and 175 of the 337 (52%) of those in the vemurafenib arm received subsequent anticancer therapies (Table 2), most commonly ipilimumab [88/338 (26%) and 93/337 (28%), respectively].

Table 2.

Subsequent therapies in ≥2% of patients in either arm

| Subsequent therapies, n (%) | Dacarbazine (n=338) | Vemurafenib (n=337) |

|---|---|---|

| Any subsequent anticancer therapy | 173 (51) | 175 (52) |

| Ipilimumab | 88 (26) | 93 (28) |

| Dacarbazine/temozolomide | 28 (8) | 64 (20) |

| Vemurafeniba | 39 (12) | 23 (7) |

| Other chemotherapy | 46 (14) | 24 (7) |

| Dabrafenib | 7 (2) | 7 (2) |

| BRAF inhibitor NOS | 13 (4) | 1 (<1) |

| Trametinib | 7 (2) | 5 (2) |

Commercially available vemurafenib or expanded access.

NOS, not otherwise specified.

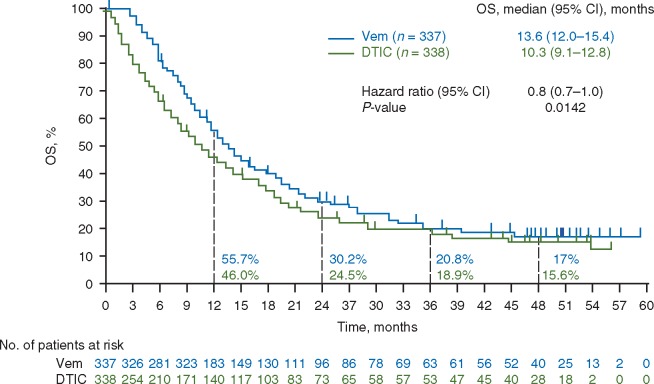

Overall survival

At the time of database lock, 271 patients in the vemurafenib arm and 259 in the dacarbazine arm had died. In the ITT population, median OS was significantly longer for vemurafenib than for dacarbazine, with or without censoring of data for dacarbazine patients who crossed over to vemurafenib (Figure 2). Median OS, censored at crossover, was 13.6 months (95% CI 12.0–15.4) for vemurafenib compared with 9.7 months (95% CI 7.9–12.8) for dacarbazine [HR 0.81 [95% CI 0.7–1.0]; P = 0.03]. Median OS without censoring at crossover was 13.6 months (95% CI 12.0–15.4) for vemurafenib compared with 10.3 months (95% CI 9.1–12.8) for dacarbazine [HR 0.81 (95% CI 0.7–1.0); P = 0.01]. Landmark OS rates at 1, 2, 3 and 4 years (without censoring at crossover) were 55.7%, 30.2%, 20.8% and 17.0%, respectively, in the vemurafenib arm, and 46.0%, 24.5%, 18.9% and 15.6%, respectively, in the dacarbazine arm. Sensitivity analyses showed significant OS benefit for vemurafenib over dacarbazine regardless of the magnitude of assumed benefit of vemurafenib after crossover.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for OS (without censoring at crossover) in the ITT population. CI, confidence interval; DTIC, dacarbazine; ITT, intention-to-treat; OS, overall survival; Vem, vemurafenib.

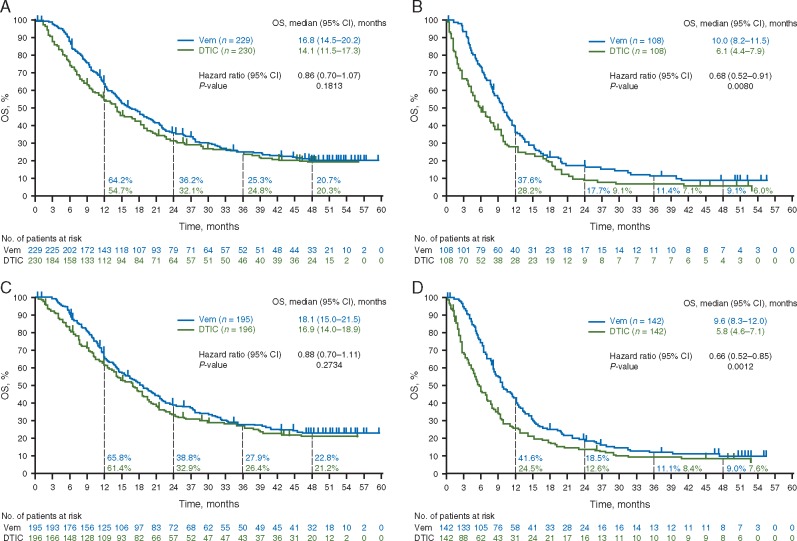

OS benefit for vemurafenib over dacarbazine was greatest in the following subgroups: age ≥65 years; stage M1c disease; elevated baseline LDH level; ECOG PS of 1 and no prior adjuvant therapy. In the vemurafenib group, median OS was longer in patients with an ECOG PS of 0 than in those with an ECOG PS of 1 [16.8 (95% CI 14.5–20.2) versus 10.0 (95% CI 8.2–11.5) months], and in those with normal versus elevated baseline LDH level [18.1 (95% CI 15.0–21.5) versus 9.6 (95% CI 8.3–12.0) months] (Figure 3). Similarly, in the dacarbazine group, median OS was longer in patients with ECOG PS of 0 versus 1 [14.1 (95% CI 11.5–17.3) versus 6.1 (95% CI 4.4–7.9) months], and those with normal versus elevated LDH [16.9 (95% CI 14.0–18.9) versus 5.8 (4.6–7.1) months] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for OS (without censoring at crossover) for patients with (A) ECOG PS 0, (B) ECOG PS 1, (C) LDH level normal and (D) LDH level elevated. CI, confidence interval; DTIC, dacarbazine; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; OS, overall survival. Vem, vemurafenib.

A descriptive summary of baseline disease characteristics of patients alive at the 3- and 4-year landmarks shows that these patients were more likely to have had favourable prognostic characteristics at baseline, including normal LDH level, ECOG PS of 0 and stage M1a/b disease, compared with the ITT population (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The survival benefit associated with vemurafenib in long-term survivors (ie, patients alive at 3 and 4 years) was most pronounced in patients aged ≥65 years and in patients with ≥3 metastatic sites at baseline.

Patients without progression on vemurafenib

At the time of database lock, 36 of the 336 patients in the vemurafenib arm had not experienced disease progression. Most of these patients had an ECOG PS of 0 [27 patients (75%)], M1c disease [22 patients (61%)] and normal LDH levels [21 patients (58%)] at baseline (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The median duration of treatment with vemurafenib for these 36 patients was 24.0 months (range 0.4–57.1). Reasons for treatment discontinuation were death (n = 7), adverse event (AE) (n = 6), refused treatment (n = 4), withdrawal of consent (n = 3) and other (n = 16). Of the 16 patients who discontinued for other reasons, 10 were rolled over into a vemurafenib extension study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID, NCT01739764). Neither median PFS nor OS was estimable.

Post-progression treatment with BRAF or MEK inhibitors following vemurafenib treatment

Among patients randomized to receive vemurafenib, 20 received post-progression anticancer treatment with a BRAF and/or MEK inhibitor. The median OS in this small subset of patients was 36.0 months (95% CI 18.0–not estimable).

Safety

The safety profile of vemurafenib was similar to profiles seen in previous publications (Tables 3 and 4) [1, 17] Patients initially assigned to the dacarbazine arm who crossed over to vemurafenib were included in the vemurafenib arm for safety analyses.

Table 3.

Most common AEs occurring in ≥20% of patients in either arm, regardless of attribution to study drug

| AEs, n (%) | Dacarbazine (n=287) | Vemurafenib (n=336) |

|---|---|---|

| ≥1 AE | 266 (93) | 334 (99) |

| Most common AEs | ||

| Rash (combined terms)a | 16 (6) | 239 (71) |

| Arthralgia | 11 (4) | 189 (56) |

| Alopecia | 7 (2) | 162 (48) |

| Fatigue | 101 (35) | 159 (47) |

| Photosensitivity reaction | 13 (5) | 136 (40) |

| Nausea | 128 (45) | 132 (39) |

| Diarrhoea | 36 (13) | 124 (37) |

| Headache | 29 (10) | 114 (34) |

| Hyperkeratosis | 1 (<1) | 99 (29) |

| Skin papilloma | 1 (<1) | 97 (29) |

| Pruritus | 5 (2) | 86 (26) |

| Dry skin | 2 (<1) | 80 (24) |

| Decreased appetite | 24 (8) | 76 (23) |

| Pain in extremity | 19 (7) | 76 (23) |

| Pyrexia | 28 (10) | 75 (22) |

| Vomiting | 77 (27) | 74 (22) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin | 2 (<1) | 66 (20) |

| Constipation | 72 (25) | 53 (16) |

Preferred terms (in decreasing order of incidence) include: rash, erythema, rash maculo-papular, folliculitis, rash papular, dermatitis, rash erythematous, rash generalized, rash macular, rash pustular, dermatitis allergic, rash follicular, rash pruritic, dermatitis exfoliative, dermatitis bullous, drug eruption, exfoliative rash, generalized erythema, rash vesicular and toxic skin eruption.

AEs, adverse events.

Table 4.

Serious AEs occurring in ≥2% of patients in either arm

| Serious AEs, n (%) | Dacarbazine (n=287) | Vemurafenib (n=336) |

|---|---|---|

| ≥1 serious AE | 52 (18) | 165 (49) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin | 2 (<1) | 66 (20) |

| Keratoacanthoma | 3 (1) | 36 (11) |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 2 (<1) | 10 (3) |

| Malignant melanoma | 0 | 7 (2) |

AEs, adverse events.

A total of 334 of 336 patients (99%) in the vemurafenib arm and 266 of 287 patients (93%) in the dacarbazine arm reported at least one AE. The most common AEs (occurring in ≥20% of patients) in the vemurafenib arm were rash, arthralgia, alopecia, fatigue, photosensitivity reaction, nausea, diarrhoea, headache, hyperkeratosis, skin papilloma, pruritus, dry skin, decreased appetite, pain in extremity, pyrexia, vomiting and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin (Table 3). The most common AEs (occurring in ≥20% of patients) in the dacarbazine arm were nausea, fatigue, vomiting and constipation (Table 3). A summary of all AEs by treatment arm and grade can be found in the supplement (supplementary Tables S2 and S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Serious AEs were reported in 165 of 336 patients (49%) in the vemurafenib arm and 52 of 287 patients (18%) in the dacarbazine arm (Table 4). Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin was reported in 66 of 336 patients (20%) in the vemurafenib group, compared with 2 of 287 patients (<1%) in the dacarbazine group; keratoacanthoma was reported in 36 of 336 patients (11%) in the vemurafenib group and 3 of 287 patients (1%) in the dacarbazine group (Table 4).

Treatment was discontinued because of AEs in 25 of 336 patients (7%) in the vemurafenib group and 5 of 287 patients (2%) in the dacarbazine group. AEs resulting in discontinuation in the vemurafenib arm included arthralgia (n = 3), dysphagia (n = 2), blood bilirubin increased (n = 2), rash (n = 2) and thrombocytopenia, cognitive disorder, dehydration, gait disturbance, myocardial infarction, pneumonia, fatigue, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, choking, general physical health deterioration, blood creatine phosphokinase increased, myoglobin blood increased, toxic skin eruption, renal impairment, myalgia, conjunctival hyperaemia, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, oesophageal pain, uveitis, diplopia, seizure, pancreatitis, pleural effusion, pleuritic pain, atrial fibrillation, scleritis, acute hepatitis, cyanosis and peripheral neuropathy in 1 patient each. AEs resulting in discontinuation in the dacarbazine arm included hypotension, dyspnoea, pleural effusion, nausea, vomiting, cerebrovascular accident and pulmonary embolism in one patient each.

Discussion

The final OS analysis of the BRIM-3 trial shows that vemurafenib continues to be associated with improved OS compared with dacarbazine after long-term follow-up, though the benefits need to be balanced against toxicities. After long-term follow-up of the BRIM-3 study, the safety profile of vemurafenib was similar to that observed in earlier analyses, with no new safety signals identified [1, 17]. A plateau in the OS curves was observed beyond ≈3 years, suggesting that patients who survive this long are likely to have good outcomes. However, convergence of OS curves for vemurafenib and dacarbazine was observed beginning around the same time (≈3 years), with a plateau observed in both groups. Interpretation of this convergence is confounded by early crossover of patients from dacarbazine to vemurafenib (25% of patients) and receipt of subsequent treatments (≈50% of patients in each arm). It is unclear to what extent the OS tail may be influenced by subsequent treatment with ipilimumab (received by around one-quarter of patients in each group) and other subsequent anticancer treatments. It is of interest that a similar plateau in OS beyond ≈3 years has also been observed with ipilimumab [18].

Given the extent of crossover and subsequent treatment, it is difficult to determine the contribution of vemurafenib to long-term OS outcomes in subsets of patients defined by known prognostic factors for survival. A summary of baseline characteristics of long-term survivors (i.e. patients alive at 3 and 4 years) shows that these patients were more likely to have good baseline prognostic factors (ECOG PS 0, LDH normal, lower disease stage) compared with the ITT population. Comparisons between treatment groups suggest that survival benefit with vemurafenib versus dacarbazine was more pronounced in patient subgroups defined by poor prognostic factors [i.e. older age (≥65 years) and greater disease burden (≥3 metastatic sites)]. Interpretation of these data is limited by the small numbers of patients. Vemurafenib showed a survival benefit over dacarbazine in the subset of patients with poor prognostic characteristics (ECOG PS 1 or elevated serum LDH). There was no detectable long-term OS benefit from vemurafenib versus dacarbazine among patients with more favourable survival characteristics (ECOG PS 0 or normal serum LDH). The lack of survival benefit in patients with favourable prognostic characteristics was not explained by a higher rate of crossover. Instead, survival rates reported here likely reflect the long-term outcomes that can be expected in the current era of available treatments for metastatic melanoma.

The BRIM-3 trial ushered in the era of targeted therapy against mutated BRAF in melanoma. Since the approval of vemurafenib monotherapy in 2011, the treatment landscape for BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma has changed considerably. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition offers more complete inhibition of MAPK signalling, and the combinations of dabrafenib plus trametinib and cobimetinib plus vemurafenib have both demonstrated improved response rates, PFS and OS compared with BRAF inhibitor monotherapy [2, 5–7]. The dabrafenib plus trametinib and cobimetinib plus vemurafenib combinations were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the first-line treatment of patients with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma in 2014 and 2015, respectively, and by the European Medicines Agency in 2015. Long-term OS results for these combinations are not yet available, but it is anticipated that the plateau in the OS curves will be higher than the plateau seen in this first monotherapy trial with a BRAF inhibitor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the patients and their families, and investigators and research teams who participated in this study. All investigators are listed in supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online. Third-party medical writing support was provided by Melanie Sweetlove, MSc (ApotheCom, San Francisco, CA, USA) and was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Funding

This work was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. There are no grant numbers associated with this funding. The authors also acknowledge partial support from an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG, P30 CA08748).

Disclosure

PBC: consultant or advisory role, Roche/Genentech, LICR Research, Merck, Rgenix and Scancel, honoraria, GlaxoSmithKline; CR: consultant or advisory role, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Amgen, Merck and Roche; JL: consultant or advisory role, Roche/Genentech, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline and Bristol-Myers Squibb, research funding (institution), MSD, Novartis, Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb; JBH: consultant or advisory role, Roche/Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Neon, honoraria, Roche/Genentech, Novartis, Pfizer and Neon, research funding (institution), MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb and GlaxoSmithKline; AR: consultant or advisory role, Roche, Pfizer, Merck and Amgen, stock or other ownership, Compugen, CytomX, Five Prime and Kite Pharma; DH: research funding, Bristol-Myers Squibb, MSD and GlaxoSmithKline; OH: consultant or advisory role and honoraria, Amgen, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck, speakers’ bureau, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Genentech and Amgen, research funding, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celldex, Genentech, Immunocore, Incyte, Merck, Merck Serono, Medimmune, Novartis, Pfizer, Rinat and Roche; PAA: consultant or advisory role, Roche/Genentech, MSD, Ventana, Novartis, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Array, research funding, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ventana; AT: consultant or advisory role, Agenus, Lytrix and Merck; PL: consultant or advisory role, Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen and Chugai, speakers’ bureau, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Chugai, investigator, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen and Novartis; RD: consultant or advisory role, Novartis, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, GlaxoSmithKline and Amgen, research funding, Novartis, MSD, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche and GlaxoSmithKline; JAS: consultant or advisory role and honoraria, Roche/Genentech; KTF: consultant or advisory role and honoraria, Roche/Genentech; IChang: current employment, stock ownership, honoraria, consultant or advisory role, speakers’ bureau, travel, accommodations or expenses and patents, Genentech; SC: current employment, Genentech, stock ownership, Roche, Gilead Sciences, Teva, Celgene and Johnson & Johnson; ICaro: current employment and stock ownership, Genentech/Roche; AH: consultant or advisory role and honoraria, Roche, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Medimmune, Mela Sciences, Merck Serono, MSD/Merck, Novartis and Oncosec, research funding, Roche, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Mela Sciences, Merck Serono, MSD/Merck, Novartis and Oncosec; GAM: consultant or advisory role, Provectus, research funding, Pfizer, Celgene and Ventana, travel, accommodation or expenses, Roche and Novartis.

References

- 1. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C. et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 2507–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dréno B. et al. Combined vemurafenib and cobimetinib in BRAF-mutated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hauschild A, Grob J-J, Demidov LV. et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 380: 358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Masuda S, Izpisua Belmonte JC.. Trametinib for patients with advanced melanoma. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: e409–e410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H. et al. Combined BRAF and MEK inhibition versus BRAF inhibition alone in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1877–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J. et al. Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372: 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H. et al. Dabrafenib and trametinib versus dabrafenib and placebo for Val600 BRAF-mutant melanoma: a multicentre, double-blind, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 386: 444–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hodi FS, O'Day SJ, McDermott DF. et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV. et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2521–2532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B. et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weber JS, D'Angelo SP, Minor D. et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R. et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ascierto PA, Kirkwood JM, Grob J-J. et al. The role of BRAF V600 mutation in melanoma. J Transl Med 2012; 10: 85.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C. et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature 2002; 417: 949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T. et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2135–2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM. et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell 2004; 116: 855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McArthur GA, Chapman PB, Robert C. et al. Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAFV600E and BRAFV600K mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schadendorf D, Hodi FS, Robert C. et al. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in metastatic or locally advanced, unresectable melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1889–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.