Abstract

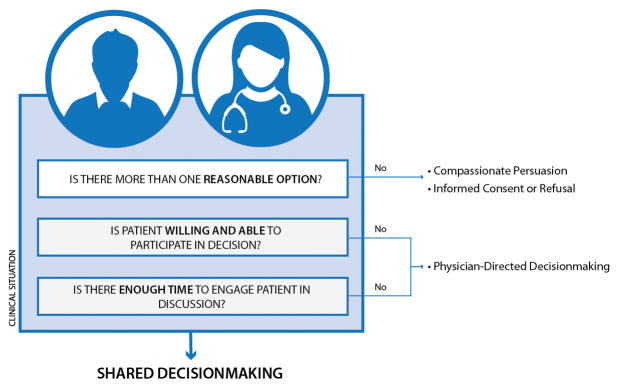

Shared decisionmaking (SDM) has been proposed as a method to promote active engagement of patients in emergency care decisions. Despite the recent attention SDM has received in the emergency medicine community, including being the topic of the 2016 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference, misconceptions remain regarding the precise meaning of the term, the process, and the conditions under which it is most likely to be valuable. With the help of a patient representative and an interaction designer, we developed a simple framework to illustrate how SDM should be approached in clinical practice. We believe SDM should be the preferred or default approach to decisionmaking, except in clinical situations where three factors interfere. These three factors are lack of: 1) clinical uncertainty or equipoise, 2) patient decisionmaking ability, and 3) time, all of which can render SDM infeasible. Clinical equipoise refers to scenarios in which there are two or more medically reasonable management options. Patient decisionmaking ability refers to a patient’s capacity and willingness to participate in his/her emergency care decisions. Time refers to the acuity of the clinical situation (which may require immediate action) and the time that the clinician has to devote to the SDM conversation. In scenarios where there is only one medically reasonable management option, informed consent is indicated, with compassionate persuasion employed as appropriate. If time or patient capacity are lacking, physician-directed decisionmaking will occur. With this framework as the foundation, we discuss the process of SDM and how it can be employed in practice. Finally, we highlight five common misconceptions regarding SDM in the ED. With an improved understanding of SDM, this approach should be used to facilitate the provision of high-quality, patient-centered emergency care.

Keywords: Shared Decisionmaking, Conceptual Model, Emergency Department

Introduction

Emergency care is becoming increasingly complex.1 As the number of tests, treatments, and clinical pathways continues to increase, patients and clinicians are faced with an increasing number of decision points. This trend coupled with an increased commitment to patient-centered care2 has expanded the potential for patient engagement to influence the course of emergency care. Shared decisionmaking (SDM) has been proposed as a method to actively engage patients in their healthcare decisions. SDM is defined as “a collaborative process in which patients and providers make health care decisions together, taking into account the best evidence available, as well as the patient’s values and preferences.”3 Although the general principles of SDM have almost certainly been used, at least in part, by emergency physicians ad hoc for decades, the systematic use and evaluation of SDM in the Emergency Department (ED) remains in its infancy. Despite the increased recent attention SDM has received in the emergency medicine community,4,5 including being the topic of the 2016 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference6, misconceptions remain regarding the precise meaning of the term, the process, and when it should be used.

In this paper, we present a simple framework (see Figure) to demonstrate how SDM fits into broader decisionmaking in the ED. We believe that SDM should be the default strategy for all significant emergency care decisions and should only be replaced by other approaches when one or more of the three essential factors are absent. This new framework could lead to a greater understanding of which clinical scenarios are amenable to SDM, minimize the misconceptions surrounding this approach, and help emergency physicians employ SDM in their clinical practice.

Figure.

Part 1: Is this clinical scenario appropriate for Shared Decisionmaking?

Three Factors Necessary for Shared Decisionmaking

At least three factors, all of which exist upon a spectrum, play a role in determining whether a decision in the ED is appropriate for SDM. These three factors are: 1) clinical uncertainty/equipoise, 2) patient (or surrogate) ability to engage in decisionmaking, and 3) time. SDM in the ED is appropriate when all three factors are present (See Figure). Since these factors are somewhat subjective, in practice there will likely be variation between clinicians regarding when they are deemed to be present. We explore each factor individually below. Assessment of these factors can occur in any order, not necessarily in the one presented in the figure, and often occur in a dynamic, non-linear fashion. Of note, SDM need not be solely performed with the patient but can be performed with a surrogate as well: a parent in the case of a young child or a health care proxy in the case of a cognitively impaired or incapacitated patient. Henceforth, when we refer to “patients” we do so with the understanding that we are also including surrogates.

Factor 1: Clinical Uncertainty or Equipoise

For many conditions in the ED, there is certainty regarding the single best, evidence-based course of action (e.g., antibiotics for sepsis); for many others, however, there is more than one reasonable option. Equipoise in the clinical context has been defined as a situation where available options are roughly in balance with regard to the potential for harm and benefit.7 Equipoise exists when there are two or more medically reasonable management options, either of which could be favored based on the patient’s values and preferences. We include uncertainty with equipoise to highlight the many situations where we are uncertain about the best course of action for a particular patient, even when risks and benefits are not perfectly balanced. In these situations, SDM should be the default approach to decisionmaking. However, if there is clearly only one medically reasonable option, then SDM is no longer appropriate.

Consider, for example, the decision to admit or discharge a patient with possible acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and an unremarkable ED cardiac diagnostic evaluation.8 Both disposition decisions could be deemed medically reasonable, and yet could have vastly different repercussions for the patient. If the patient is admitted, they will incur costs and experience the inconvenience of hospitalization, the possibility of iatrogenic injury or false-positive findings. On the other hand, if the patient is discharged, s/he risks recurrence of pain and the low likelihood of a missed ACS. The patient may prefer to avoid the disruption associated with hospitalization and undergo provocative cardiac testing as an outpatient, even if this is associated with a small medical risk. Conversely, the patient may feel unsafe going home and prefer to expedite the evaluation by being admitted.

Other examples include i) immediate antibiotics or a “wait and see” approach for acute otitis media,9 ii) choice of anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation,10 iii) initial imaging for acute flank pain,11 and, iv) thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke.12

Such conditions have been described as “preference-sensitive,” defined as conditions where treatment options exist that come with trade-offs between potential harms and benefits for the patient.13 In the context of emergency care, there are many decisions in which equipoise could be considered to exist including those that involve testing, therapy, or disposition.4,5 Clinical decisions in the ED lie on a spectrum from complete perceived certainty to equipoise/uncertainty. Notably, clinical equipoise is a dynamic element which can change over time as new evidence emerges or the patient’s condition changes.

Compassionate Persuasion

For scenarios with uncertainty/equipoise, SDM is the preferred strategy for decisionmaking, assuming time and patient ability permit. For clinical decisions where medical benefit clearly outweighs the risks and the treatment is in line with the patient’s goals of care, SDM is not appropriate; rather, the paradigm of informed consent (or informed refusal) will guide decisionmaking. If the patient is hesitant to receive care that is clearly in the best interest of his/her health and in line with his/her values, the clinician should attempt compassionate persuasion. Compassionate persuasion is a benevolent attempt to convince a patient to receive care that they do not initially want, if it is, in fact, consistent with his/her values. This persuasion may appeal to a patient’s rational or emotional faculties and is justified if guided by the ethical principle of beneficence. It should start with an exploration of why the patent is declining care. Although guided by the principle of beneficence, compassionate persuasion must always be balanced with respect for patient autonomy. For example, if a patient with an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) resists admission to the hospital, the clinician should first try to understand the basis of their resistance and, if appropriate, try to persuade him/her to stay and receive care. If the patient is refusing care because they need to be at work the next day, it is reasonable to remind them that a phone call or letter from the doctor to the employer can be made and is often enough to appease the employer. If, on the other hand, the patient’s religious beliefs preclude them from receiving a treatment, such as a blood transfusion, the clinician should seek to understand these preferences, and respect them by not attempting to impose his/her own belief system on the patient.

Factor 2: Patient’s Decisionmaking Ability

For a clinician to successfully engage a patient in SDM, the latter must be willing and able to participate in medical decisions. First, the patient must have the capacity to make informed decisions. Patients can lose decisionmaking capacity for a variety of reasons including cognitive impairment, delirium due to acute medical illness, severe mental illness, and intoxication. Without basic capacity, SDM is clearly inappropriate and other decisionmaking strategies must be employed, unless a proxy is present. Although capacity is often thought of as a binary variable – either a patient has the mental status to make decisions, or s/he does not14 – in reality, this factor lies upon a continuum and may be dynamic over time. Second, a patient must have the cognitive skills and self-efficacy to make potentially complex decisions about their medical care. Patients who are in the ED with acute complaints may have reduced self-efficacy with regard to decisionmaking due to pain, stress, or anxiety, potentially making them less receptive to SDM. Cultural factors may also play a role in determining the patients’ willingness to engage in SDM. In the case of a patient who is unable or unwilling to participate in decisionmaking, and there is no access to surrogates, SDM is not appropriate and care should proceed based on physician-directed decisionmaking. Low health literacy and numeracy should not preclude attempts at SDM.15 It is both the responsibility and the challenge of the clinician to explain options clearly and to make decisions accessible to patients, even to those with lower education. Additionally, the patient’s willingness and ability to participate should be actively assessed, often simply by beginning the SDM conversation. The clinician can and should cultivate self-efficacy and promote patient autonomy by empowering patients with information, options, and positive language. Clinicians should not make assumptions about patients’ preferences or their ability to be involved, as they are often wrong about a patient’s desired level of involvement.16

Factor 3: Time

Emergency medicine often involves the evaluation and treatment of acute, time-sensitive medical conditions. Emergency physicians must also be cognizant of the overall flow of the ED, the safety of the entire population of patients for which they are responsible, and the opportunity cost of spending additional time with an individual patient. For these reasons, SDM should only be employed when time allows. If a delay in decisionmaking could put the patient, or other contemporaneous patients, at risk of a bad outcome, then SDM may not be appropriate or should be deferred until time allows. If too little time exists, and a decision must be made quickly, then SDM is not appropriate and, again, physician-directed decisionmaking should proceed. ED interventions, both diagnostic and therapeutic, vary widely in their time-sensitivity. This time-sensitivity lies upon a spectrum from emergent, requiring action within seconds to minutes, to non-urgent, requiring action within several hours. Most clinical decisions in the ED are not subject to such acute time-sensitivity and can be discussed with the patient prior to clinical action. With proper training and practice, SDM can be accomplished efficiently by the skilled clinician in the majority of cases, thus enabling delivery of personalized, high-quality care for the entire population of patients for which the physician is responsible.

Although a highly time-sensitive condition may make SDM more difficult, these encounters could still warrant SDM.17 Consider, for example, the case of a patient with terminal cancer who presents to the ED with severe respiratory distress. Although the decision to intubate should be made quickly, discussion with surrogates regarding goals of care and code status should be attempted in an effort to align interventions with the patient’s values and wishes. Life-saving interventions should not be withheld for the sake of SDM but, if the intervention being considered might not align with the patient’s overall goals of care, surrogates should be engaged as quickly as possible.

Part 2: Having the Shared Decisionmaking conversation

The clinician should be the one to initiate the SDM conversation, assuming the three factors set forth in the Figure are met: there is more than one reasonable option, the patient is willing and able to participate, and there is sufficient time. There are four general steps to engaging in SDM.

Step 1) Acknowledge that a clinical decision needs to be made

First, the clinician should make it clear what s/he is going to discuss and why. This can be prefaced by stating what is currently known about the clinical situation. Then a clear statement should be made indicating that a decision with various options needs to be discussed. Potential phrases include, “We have a decision to make…” or “We have a couple of options going forward…”

Take, for example, a patient with possible acute appendicitis. The following script could be used:

“Anytime a patient comes to the ED with pain in their right lower abdomen, we consider the possibility of appendicitis. Your temperature, urine and blood tests were all normal so far. However, the ultrasound was not able to see your appendix. Going forward, we have a decision to make…so let’s talk about the options and consider the decision together.”

Step 2) Share information regarding management options and the potential harms, benefits, and outcomes of each

This step will vary based on how much is known about an individual patient’s risk and can be challenging in low-evidence scenarios. This discussion could include both logistical details and estimates of risk. Information should be provided in a stepwise fashion at a pace the patient can understand, in an effort to avoid cognitive overload. The information should also be expressed in lay language, free of medical jargon.

“Based on what we know, there is still a small chance you have appendicitis. One option would be to do a CT scan of your abdomen now. This is like a very powerful x-ray and involves some radiation exposure. It would involve staying another few hours in the ED and waiting for the radiologist to provide a report. If you prefer, you could also go home and come back in 6–8 hours if the pain returns, you spike a fever, or feel worse in any way. I think both options are reasonable.”

More risk and logistical information can be provided based on the patient’s specific follow-up questions. Decision aids, if available, can facilitate the communication of options and accompanying probabilities.

Step 3) Explore patient values, preferences, and circumstances

This is best accomplished by asking questions to facilitate a conversation about what the patient is thinking, what matters to them, and what social factors may be at play. Examples include:

“How are you feeling now? What are you thinking about when you hear these two options? What practical concerns do you have? What are you worried about? Do you live alone? Can you come back easily to the ED? What is most important to you?”

Step 4) Decide together on the best option for the patient given his/her values, preferences, and circumstances

Shared decisionmaking should be viewed as a conversation. Ultimately, the conversation should result in a mutual decision. This can be based on suggestions from the clinician, but ideally the patient would be provided sufficient time and conversational space to engage in the decisionmaking process. The clinician should try to resist dictating the course of action, even in the event of the commonly asked question: “Well, what would you do, doctor?” as the clinician’s personal preferences and values may or may not match the patient’s. The patient may be asking this question to access the doctor’s intuition and overall clinical gestalt. Many patients have a tendency to trust doctors with regard to their knowledge and judgment. It is the clinician’s responsibility to understand the patient’s preferences and values and help them make a decision most consistent with these. The clinician should be careful not to unduly sway the patient in one direction or another. If pressed to make the decision, clinicians may offer suggestions as to how the patient’s values could line up with the various options.

“I can share my opinion as to which choice I would make for myself if I was facing the same circumstances. You may completely agree with my choice or you may question whether or not it is suitable for you. If you are nervous about going home or you feel like you’re getting worse, it might make sense to have the CT now. If you are feeling better and you feel like you can come back if you feel worse, you may prefer to leave and get some rest in the comfort of your own home.”

Clinicians should be aware that many patients will not be accustomed to making collaborative decisions with their physicians, particularly one who is new to them, and may not volunteer their values and preferences without considerable prompting. Transmission of knowledge alone may not be sufficient—clinicians should be aware that no matter how well they convey the necessary information to a patient, s/he may not feel empowered to voice their preferences, concerns, or questions.18 The clinician should strive to create an environment where the patient feels at ease expressing their preferences and asking questions.

Decision Aids

Patient decision aids, also known as decision support interventions, are evidence-based tools designed to increase patient understanding of medical options and possible outcomes, facilitate conversations between patients and clinicians, and improve patient engagement.19 ED decision aids have the potential to standardize the SDM process and activate patients by offering them information and encouraging them to explore and express their preferences. Ideally, these decision aids would provide individualized probability estimates and would not be “one size fits all”. However, unstructured SDM can be performed without using a decision aid; lack of one should not preclude attempts at SDM. There is currently limited research on ED-based decision aids8 but there will surely be further work in this area in the coming years.20–22 A full discussion on the effectiveness and use of decision aids is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

Part 3: Misconceptions about SDM

Misconception #1: Shared decisionmaking is the same as informed consent/refusal

SDM is sometimes conflated with the related, but separate, concept of informed consent or informed refusal. The key difference is that with informed consent/refusal, there is one clear medically superior option, while with SDM there are two or more medically reasonable options, i.e. there is clinical equipoise. Informed consent is a largely legal construct, whereas SDM is a largely ethical construct. Informed consent relies heavily on the medical risks and benefits, whereas SDM relies heavily on the patients’ values and preferences.

Consider the example of an adult patient presenting to the ED with acute chest pain found to have evidence of a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Based on high levels of evidence, this patient should receive in-patient medical therapy.23 The clinician should still seek to communicate with the patient regarding the potential harms and benefits of the interventions as well as educate the patient regarding the diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy. Once this is accomplished, a professional recommendation should be made and informed consent should be sought. If a patient is reluctant to undergo such treatment, the clinician should explore the reasons for this resistance and employ compassionate persuasion as described above, if the patient’s values are aligned with receiving medical care to decrease morbidity and mortality. Persuasion, in this case, is not coercion and is ethically justifiable.24 Since refusing care would be not considered medically reasonable, this is not an exercise in SDM. However, patients may rationally choose to forgo medical care for valid, personal reasons. In this situation, respect for patient autonomy would take precedence.

Misconception #2: Shared decisionmaking is simply good clinician-patient communication

SDM has also been misappropriated to signify good clinician-patient communication and/or patient education. Although effective clinician-patient communication and education are necessary conditions for a successful SDM interaction, they are insufficient, in and of themselves, to constitute SDM and represent distinct concepts. SDM, as stated above, requires some level of equipoise between two (or more) medically reasonable options. Discussing the rationale behind clinical actions, be they testing, treatment, or disposition, should be a part of every ED encounter, regardless of equipoise. These discussions can happen regardless of the degree to which the patient is engaged in the decisionmaking process. Effective communication is essential to all patient care but, alone, does not constitute SDM.

Misconception #3: The goal of shared decisionmaking is to decrease resource utilization

While SDM has been promoted as a mechanism to improve resource utilization,25 it should be noted that the imperative for SDM is not a reduction in resource utilization. SDM, rather, rests on principles of patient-centered care including respect for patient autonomy, i.e., that a patient’s informed preferences should be the basis for medical action.26 SDM may, as a secondary effect of incorporating evidence-based information in the decisionmaking conversation, reduce unnecessary care, but this should not be the primary goal of engaging patients in SDM.27

Misconception #4: Shared decisionmaking is a means of shifting responsibility for decisions to the patient, leaving the patient to make the medical decision alone, once informed

SDM is not a means for the clinician to abdicate responsibility for the medical decision. It does not constitute patient abandonment. Rather, SDM implies that the final decision be made by the clinician and the patient together. SDM should not replace the clinician’s expertise in educating, counseling, and guiding the patient through the decisionmaking process28, nor should it be used expressly to decrease the clinician’s medico-legal risk. However, as a model of good communication, it is reasonable to believe that genuinely engaging in SDM may decrease a clinician’s malpractice risk.29 SDM is not abandoning patients to make decisions alone but, rather, inviting them to collaborate in the decisionmaking conversation to the extent they feel comfortable.30,31

Misconception #5: Shared decisionmaking is offering patients any intervention they would like

As stated above, SDM is only appropriate when two or more medically reasonable options exist. SDM is not a call for “fast-food medicine” whereby patients are encouraged to “order from a menu.” For example, if a patient presents with mild, non-traumatic low back pain of short duration without any neurological signs or symptoms, advanced imaging should not be offered in the name of SDM since it is not medically indicated.

Conclusion

As emergency physicians adapt to the growing complexities of emergency care, SDM has emerged as the preferred approach to providing high-quality, patient-centered care in the ED. In this paper, we discuss three factors necessary for SDM to be performed. These three factors: clinical equipoise/uncertainty, patient decisionmaking ability, and time, all exist upon a spectrum and are often assessed in a dynamic, non-linear fashion. If a clinical scenario lacks equipoise, a professional recommendation should be made by the clinician, using compassionate persuasion as needed, until informed consent or refusal is obtained. If the patient is not willing and able to participate in the decision, or too little time exists, then physician-directed decisionmaking should proceed. Our guiding framework demonstrates the potential broad reach that SDM can have in emergency medicine, and also to recognize those clinical scenarios where other approaches are necessary. Barring these three factors, we believe SDM should be the default approach to decisionmaking. Next, we outline the four steps emergency physicians should take when engaging patients in SDM and clarify common misconceptions regarding SDM in the ED. We hope that emergency physicians can utilize this framework to successfully implement SDM into their practice.

Clinical Vignette.

A 59-year-old male with a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia presents to the Emergency Department (ED) after experiencing an unwitnessed syncopal episode at his home while walking to the bathroom. His prodromal symptoms include brief dizziness, described as light-headedness, but no chest pain, palpitations, or dyspnea. He presents to the ED because he is worried that he has had a heart attack or a stroke. On exam, there are no signs of head trauma and no neurological deficits. Further, there is no evidence of an aortic murmur, heart failure or other abnormal cardiac findings. Serial vital signs are within normal limits. His laboratory testing, including a urinalysis, complete blood count, chemistry panel, and serial cardiac enzymes are unremarkable. His chest x-ray is normal. His electrocardiogram shows a normal sinus rhythm with non-specific T-wave changes in the precordial leads. He is now asymptomatic and feeling well. The doctor and the patient discuss possible causes of this fainting episode. The patient is relieved to hear that the work-up has uncovered no evidence of a heart attack or stroke. However, was this patient’s syncope caused by a dangerous arrhythmia? Should he be admitted for observation and further testing? This decision should be guided not only by the medical evidence and the clinician’s experience but also by the patient’s values and preferences.

The clinician approaches the patient and explains to him what is currently known— the patient has experienced “syncope,” suddenly passing out or fainting with a rapid recovery. He has no high-risk features such as dyspnea, hypotension, anemia, heart failure or coronary artery disease.32,33 His blood test and x-ray results are all reassuring. The clinician explains that a decision must now be made: whether to admit for further testing and monitoring, or discharge with expedited follow-up. The clinician then describes what these two options entail, describing the potential harms and benefits of each and stating that both are medically reasonable. The patient asks questions regarding the nature of in-patient testing and length of the admission. After some dialogue, it arises that the patient lives nearby with his wife, who is a nurse, and has a strong preference for going home. He also has ready access to a cardiologist that he can see within 2 or 3 days. The patient is discharged with return precautions and a specific follow-up plan.

Acknowledgments

Grants/Conflict of Interest:

Marc Probst is supported by a grant from the NIH/NHLBI: K23HL032052

Edward Melnick is supported by grant number K08HS021271 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Elizabeth Schoenfeld is supported by grant number R03HS024311 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Erik Hess is supported by contract #0876 from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute

Footnotes

Meetings: No prior version of this work has been presented at any meeting.

Author Contributions Statement

MP and HK conceived of the idea for the manuscript. All authors contributed significant intellectual input to the development and refinement of the conceptual framework. MB designed and edited the graphic.

References

- 1.Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard J, Vesely Edward N, Okeke ALK, et al. The Evolving Role of Emergency Departments in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2013. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Institute of Medicine; Washington (DC): 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frosch DL, Kaplan RM. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: past research and future directions. Am J Prev Med. 1999 Nov;17(4):285–294. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanzaria HK, Brook RH, Probst MA, Harris D, Berry SH, Hoffman JR. Emergency Physician Perceptions of Shared Decision-making. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Apr;22(4):399–405. doi: 10.1111/acem.12627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Frosch DL, et al. Perceived Appropriateness of Shared Decision-Making in the Emergency Department: A Survey Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2016 Jan 25; doi: 10.1111/acem.12904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. [Accessed August 1, 2016];Shared Decision Making (SDM) in the Emergency Department: Development of a Policy-Relevant, Patient-Centered Research Agenda. Available at: http://www.saem.org/annual-meeting/future-past-meetings/saem16/2016-consensus-conference.

- 7.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Rollnick S. Dual equipoise shared decision making: definitions for decision and behaviour support interventions. Implement Sci. 2009;4:75. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess EP, Knoedler MA, Shah ND, et al. The chest pain choice decision aid: a randomized trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012 May;5(3):251–259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiro DM, Tay KY, Arnold DH, Dziura JD, Baker MD, Shapiro ED. Wait-and-see prescription for the treatment of acute otitis media: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006 Sep 13;296(10):1235–1241. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess EP, Coylewright M, Frosch DL, Shah ND. Implementation of shared decision making in cardiovascular care: past, present, and future. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014 Sep;7(5):797–803. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith-Bindman R, Aubin C, Bailitz J, et al. Ultrasonography versus computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis. N Engl J Med. 2014 Sep 18;371(12):1100–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn D, Nesbitt DJ, Ford GA, et al. Development of a computerised decision aid for thrombolysis in acute stroke care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2015;15:6. doi: 10.1186/s12911-014-0127-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veroff D, Marr A, Wennberg DE. Enhanced support for shared decision making reduced costs of care for patients with preference-sensitive conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Feb;32(2):285–293. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simon JR. Refusal of care: the physician-patient relationship and decisionmaking capacity. Ann of Emerg Med. 2007 Oct;50(4):456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coylewright M, Branda M, Inselman JW, et al. Impact of sociodemographic patient characteristics on the efficacy of decision AIDS: a patient-level meta-analysis of 7 randomized trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014 May;7(3):360–367. doi: 10.1161/HCQ.0000000000000006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudak PL, Frankel RM, Braddock C, 3rd, et al. Do patients’ communication behaviors provide insight into their preferences for participation in decision making? Med Decis Making. 2008 May-Jun;28(3):385–393. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07312712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis MA, Hoffman JR, Hsu J. Impact of patient acuity on preference for information and autonomy in decision making. Acad Emerg Med. 1999 Aug;6(8):781–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014 Mar;94(3):291–309. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flynn D, Knoedler MA, Hess EP, et al. Engaging patients in health care decisions in the emergency department through shared decision-making: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;19(8):959–967. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2012.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson RT, Montori VM, Shah ND, et al. Effectiveness of the Chest Pain Choice decision aid in emergency department patients with low-risk chest pain: study protocol for a multicenter randomized trial. Trials. 2014;15:166. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess EP, Wyatt KD, Kharbanda AB, et al. Effectiveness of the head CT choice decision aid in parents of children with minor head trauma: study protocol for a multicenter randomized trial. Trials. 2014;15:253. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melnick ER, Lopez K, Hess EP, et al. Back to the Bedside: Developing a Bedside Aid for Concussion and Brain Injury Decisions in the Emergency Department. EGEMS. 2015;3(2):1136. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circ. 2014 Dec 23;130(25):2354–2394. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dubov A. Ethical persuasion: the rhetoric of communication in critical care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015 Jun;21(3):496–502. doi: 10.1111/jep.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ. Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 3;368(1):6–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1209500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elwyn GT, Montori VM. The ethical imperative for shared decision-making. Euro J for Person Centered Health. 2012;1(1):129–131. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz SJ, Hawley S. The value of sharing treatment decision making with patients: expecting too much? JAMA. 2013 Oct 16;310(15):1559–1560. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melnick ER, Shafer K, Rodulfo N, et al. Understanding Overuse of Computed Tomography for Minor Head Injury in the Emergency Department: A Triangulated Qualitative Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Dec;22(12):1474–1483. doi: 10.1111/acem.12824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beckman HB, Markakis KM, Suchman AL, et al. The doctor-patient relationship and malpractice. Lessons from plaintiff depositions. Arch Intern Med. 1994 Jun 27;154(12):1365–1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hargraves I, LeBlanc A, Shah ND, et al. Shared Decision Making: The Need For Patient-Clinician Conversation, Not Just Information. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016 Apr 1;35(4):627–629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legare F, Thompson-Leduc P. Twelve myths about shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014 Sep;96(3):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn J, McDermott D, Stiell I, et al. Prospective validation of the San Francisco Syncope Rule to predict patients with serious outcomes. Ann Emerg Med. 2006 May;47(5):448–454. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huff JS, Decker WW, Quinn JV, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope. Ann Emerg Med. 2007 Apr;49(4):431–44. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]