Abstract

Sensitivity to interaural time differences (ITDs) in envelope and temporal fine structure (TFS) of amplitude-modulated (AM) tones was assessed for young and older subjects, all with clinically normal hearing at the carrier frequencies of 250 and 500 Hz. Some subjects had hearing loss at higher frequencies. In experiment 1, thresholds for detecting changes in ITD were measured when the ITD was present in the TFS alone (ITDTFS), the envelope alone (ITDENV), or both (ITDTFS/ENV). Thresholds tended to be higher for the older than for the young subjects. ITDENV thresholds were much higher than ITDTFS thresholds, while ITDTFS/ENV thresholds were similar to ITDTFS thresholds. ITDTFS thresholds were lower than ITD thresholds obtained with an unmodulated pure tone, indicating that uninformative AM can improve ITDTFS discrimination. In experiment 2, equally detectable values of ITDTFS and ITDENV were combined so as to give consistent or inconsistent lateralization. There were large individual differences, but several subjects gave scores that were much higher than would be expected from the optimal combination of independent sources of information, even for the inconsistent condition. It is suggested that ITDTFS and ITDENV cues are processed partly independently, but that both cues influence lateralization judgments, even when one cue is uninformative.

I. INTRODUCTION

The response to sound at a given place within the cochlea can be considered as a narrowband signal with a relatively slowly varying envelope (ENV) imposed on a rapidly oscillating carrier (the temporal fine structure, TFS; Moore, 2014). Information about ENV and TFS is conveyed in the timing and short-term rate of action potentials in the auditory nerve (Rose et al., 1967; Joris et al., 2006; Heinz and Swaminathan, 2009). Differences in the timing of ENV and TFS across the two ears can be used for sound localization (Henning, 1974). Interaural time differences (ITDs) in TFS, denoted here ITDTFS, are often described as interaural phase differences (IPDs). IPDs provide very effective cues for the localization of low-frequency sinusoids, but changes in IPD typically cannot be detected for frequencies above about 1400 Hz (Hughes, 1940; Brughera et al., 2013; Füllgrabe et al., 2017; Füllgrabe and Moore, 2017). ITDs in the envelopes of complex sounds, denoted here ITDENV, can be detected for a wide range of center frequencies and for envelope modulation rates up to 500–800 Hz (Henning, 1974; Monaghan et al., 2015). The smallest detectable change in ITDENV is typically larger than the smallest detectable change in ITDTFS, but the acuity for detecting differences in ITDENV can be improved by using sounds whose envelopes have a high peak factor, as occurs for “transposed” tones (Bernstein and Trahiotis, 2002). There is evidence that the ability to discriminate changes in ITD declines with increasing age and hearing loss; this evidence is reviewed below (see also Moore, 2016). The present paper is concerned with the effects of age on the ability to detect changes in ITDENV and ITDTFS when either cue is presented alone and when the cues are presented in combination, including conditions where the cues “trade,” for example, where the ITDTFS leads at the right ear and the ITDENV leads at the left ear.

The ability to detect interaural differences in TFS can be assessed by measuring the smallest detectable change in IPD between successive sinusoidal tone bursts, keeping the envelopes of the tone bursts synchronous at the two ears. A task of this type is used in the TFS-LF test (where LF stands for low-frequency; Hopkins and Moore, 2010; Sek and Moore, 2012). In this test, four successive tone bursts are presented in each of two successive intervals. In one interval, the IPD is 0° for all four tones. In the other interval, the IPD alternates between 0 and φ across tones. The subject is asked to identify the interval in which the tones appear to move within the head and/or in which the sound is more diffuse. The value of φ is adapted to determine a threshold.

Moore et al. (2012b) used the TFS-LF test to assess the effect of age on IPD discrimination for subjects with normal hearing. They tested 35 subjects with audiometric thresholds ≤20 dB hearing level (HL) from 250 to 6000 Hz and ages from 22 to 61 yr. The test was conducted using center frequencies of 500 and 750 Hz. There were significant correlations between age and IPD thresholds at both 500 Hz (r = 0.37) and 750 Hz (r = 0.65). Scores on the TFS-LF task were not significantly correlated with absolute thresholds at the test frequency. These results confirm those of Ross et al. (2007), Grose and Mamo (2010), and Füllgrabe (2013), and indicate that a decline in sensitivity to binaural TFS with increasing age occurs by middle age. Füllgrabe et al. (2015) used the TFS-LF task with young (18–27 yr old) and older (60–79 yr old) groups of subjects, all with audiometric thresholds ≤20 dB HL for frequencies up to 6 kHz. The mean audiograms of the two groups were almost exactly matched. The older group performed significantly more poorly than the young group for both center frequencies used (500 and 750 Hz). The scores on the TFS-LF test were not significantly correlated with audiometric thresholds at the test frequencies. Overall, the results indicate that the ability to detect changes in IPD worsens with increasing age even when audiometric thresholds remain within the normal range.

The effects of age and hearing loss on the binaural processing of ENV and TFS cues were assessed by King et al. (2014). They used amplitude-modulated (AM) sinusoids as stimuli and measured the ability to discriminate IPDs imposed either on the carrier or the modulator. The carrier frequency, fc, was 250 or 500 Hz and the modulation frequency was 20 Hz. They tested 46 subjects with a wide range of ages (18–83 yr) and degrees of hearing loss. The absolute thresholds at the carrier frequencies of 250 and 500 Hz were not significantly correlated with age. Thresholds for detecting changes in ITDENV were positively correlated with age for both carrier frequencies (r = 0.62 for fc = 250 Hz; r = 0.58 for fc = 500 Hz). The correlations remained positive and significant when the effect of absolute threshold was partialled out, suggesting that increasing age adversely affects the ability to discriminate ITDENV independently of the effects of hearing loss. King et al. (2014) also found that thresholds for detecting changes in ITDENV were not significantly correlated with absolute thresholds, suggesting that hearing loss does not markedly affect the ability to process binaural ENV cues. However, thresholds for detecting changes in ITDTFS were positively correlated with absolute thresholds for both carrier frequencies (r = 0.45 for fc = 250 Hz; r = 0.40 for fc = 500 Hz), and the correlations remained positive and significant when the effect of age was partialled out. Thus, hearing loss at low frequencies does seem to adversely affect the binaural processing of TFS, as was also found by Füllgrabe and Moore (2017).

The present study extended the study of King et al. (2014) using AM tones by comparing the sensitivity to changes in ITDTFS, ITDENV, or both, for two age groups, young and older. In contrast to the study of King et al. (2014), both the young and older subjects were selected to have thresholds within the “normal” range (≤20 dB HL) at the test carrier frequencies of 250 and 500 Hz. Several of the older subjects had hearing loss for frequencies of 1000 Hz and above, but it has been shown that ITD discrimination for low-frequency sounds is not correlated with audiometric thresholds at high frequencies when the effect of age is controlled for (Moore et al., 2012a; Füllgrabe and Moore, 2017). Therefore, it seemed reasonable to assume that differences in ITD discrimination between the two groups could be ascribed to differences in age per se rather than to differences in audiometric thresholds. In experiment 1, when an ITD was present in both TFS and ENV, it was the same for TFS and ENV (as would occur naturally for a sound that was delayed at one ear relative to the other). In experiment 2, we selected pairs of values of ITDTFS and ITDENV that were equally discriminable and then assessed discrimination performance when the pairs were combined, either in a consistent manner (ITDTFS and ITDENV both leading in the same ear) or in an inconsistent manner (ITDTFS leading in one ear and ITDENV leading in the other ear).

II. EXPERIMENT 1

A. Rationale

In this experiment, we used AM tones to determine the threshold for discriminating an ITD of τ from an ITD of 0 under conditions where the ITD was applied to the envelope, the carrier, or both. We were especially interested in the effects of age on the relative ability to discriminate changes in ITDTFS and ITDENV. Specifically, we wanted to assess whether age has a greater effect on the discrimination of ITDTFS than ITDENV. If this were the case, it would indicate that the effect of age on ITDTFS discrimination cannot be explained solely by changes in “processing efficiency” with age. We were also interested in determining whether sensitivity to ITDTFS is affected by the presence of AM, even when the AM is uninformative.

B. Method

1. Subjects

There were 12 young subjects (aged 19–27 yr, mean= 22 yr, standard deviation, SD = 2 yr) and 11 older subjects (aged 62–78 yr, mean = 70 yr, SD = 4 yr). All subjects had audiometric thresholds ≤20 dB HL for the two test frequencies of 250 and 500 Hz. The interaural differences in audiometric threshold at 250 and 500 Hz were always ≤10 dB, and they were ≤5 dB in 80% of cases. The mean audiometric thresholds at 250 and 500 Hz, respectively, were 3.6 and 5.3 dB HL for the young group and 8.0 and 11.2 dB HL for the older group. Hence, the older group had audiometric thresholds that on average were 5–6 dB higher than for the young group. The possible consequences of this are discussed later. Four of the older subjects had audiometric thresholds ≤20 dB HL for all audiometric frequencies up to 4000 Hz and ≤30 dB HL at 8000 Hz, so their hearing can be considered as normal or near-normal. The remaining older subjects had mild-to-moderate hearing loss at high frequencies. All of the young subjects had audiometric thresholds ≤20 dB HL for all audiometric frequencies up to 8000 Hz.

2. Stimuli and procedure

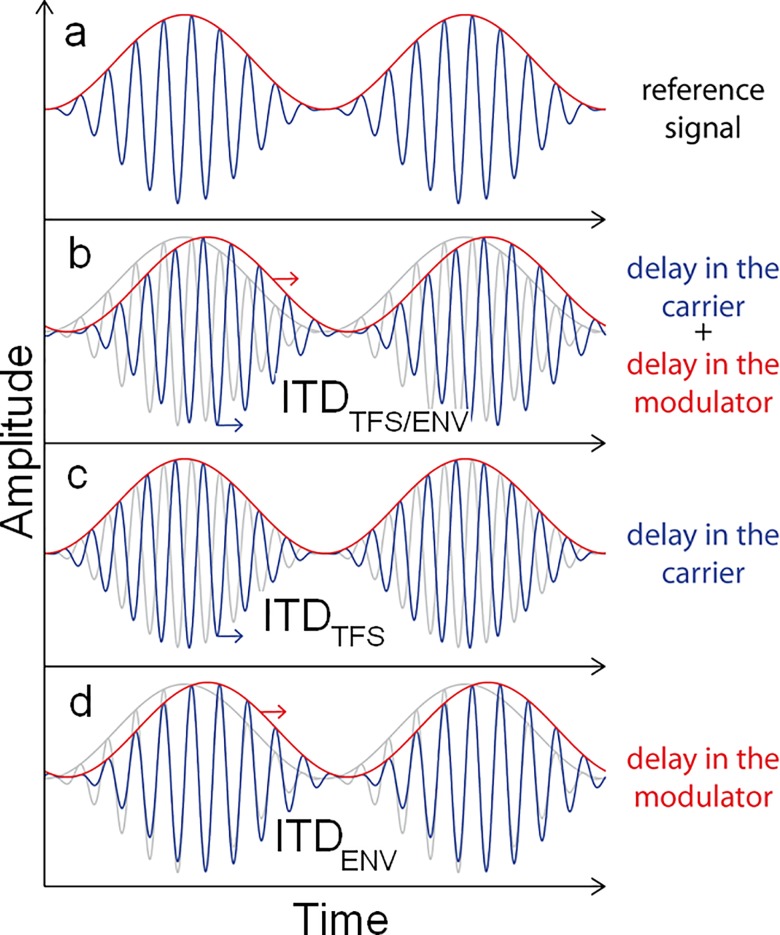

Sensitivity to changes in ITDTFS and ITDENV from a reference of 0 was assessed using 100% AM sinusoidal carriers. The stimuli are illustrated schematically in Fig. 1. The diotic reference stimulus is illustrated in Fig. 1(a); the waveform (blue online) and its envelope (red online) are shown. For the target stimulus, the ITD was present in both the modulator and the carrier [ITDTFS = ITDENV = τ, denoted ITDTFS/ENV, Fig. 1(b)], in the carrier only, with synchronous modulator at the two ears [ITDTFS = τ, ITDENV = 0, Fig. 1(c)], or in the modulator, with the carrier in-phase at the two ears [ITDTFS = 0, ITDENV = τ, Fig. 1(d)]. The carrier frequency was 250 or 500 Hz and the modulator frequency was 25 or 50 Hz. The starting phase of the modulator was selected randomly for each stimulus from a uniform distribution with a range from 0 to 360°. Sensitivity to ITDTFS was also measured for an unmodulated sinusoidal carrier with synchronous onset/offset ramps at the two ears. For convenience, the unmodulated carrier is designated as having an AM rate of 0 Hz.

FIG. 1.

(Color online) Schematic diagram of the stimuli used in experiment 1. The waveform (rapid oscillation, blue online) and envelope (slower oscillation, red online) of the diotic reference stimulus are shown in (a). (b)–(d) show the waveforms and envelopes of the target stimuli in the lagging ear, with ITDs in both the carrier and the modulator [ITDTFS/ENV, (b)], the carrier only [ITDTFS, (c)], and the modulator only [ITDENV, (d)]. In panels (b) and (c), the faint lines show the waveform and envelope in the leading ear. In (b), to make the ITDs clearly visible, ITDENV was greater than ITDTFS. In the actual experiment ITDENV was equal to ITDTFS.

The task was to detect a change in ITD relative to a reference ITD of 0, using a stimulus structure similar to that for the TFS-LF task described above (Hopkins and Moore, 2010). In each trial there were two successive intervals, each containing four 400-ms tone bursts (including 50-ms raised-cosine rise/fall ramps). This relatively long duration was chosen to reduce the effects of binaural sluggishness, the inability of the auditory system to track changes in the position of a sound source when the ITD is changed at a high rate (Blauert, 1972). The silent gap between stimuli within an interval was 30 ms and the silent gap between intervals was 200 ms. In one interval, selected randomly, all four stimuli were diotic. In the other interval, stimuli one and three were diotic and stimuli two and four contained an ITD in the ENV, the TFS, or both; the stimulus at the right ear led the stimulus at the left ear. Subjects were told to indicate the interval in which the sounds appeared to change in some way, for example, in apparent location or diffuseness. Correct-answer feedback was given after the response on each trial. Note that this task does not require the subject to indicate the relative position of the sounds, but only to detect the interval in which the position changed or the image changed in any way. This is preferable to a task where a subject must indicate whether a sound moves to the left or right, as a sound with a large IPD, such as 180°, may be heard either to the right or left (Blodgett et al., 1956; Kunov and Abel, 1981).

The tones were presented to each ear at the same sensation level (SL) of 30 dB. The level was specified relative to the absolute threshold for a pure tone at the test frequency, measured using 400-ms tones and an adaptive two-alternative forced-choice (2-AFC) task tracking 71% correct (Levitt, 1971). Tones presented with equal SL across ears with an ITD of zero would be expected to be lateralized approximately centrally by subjects with bilaterally normal hearing at the test frequency, although this was not critical for performance of the task, as noted above.

At the beginning of a run, the ITD was set to a large value, which was expected to be easily discriminable. Pilot runs indicated that a suitable starting value of ITDTFS and ITDTFS/ENV was 500 μs, while the starting value of TFSENV needed to be markedly higher, at 6000 μs. While the value of 6000 μs is greater than the largest ITD that would occur naturally, such large ITDs can be detected and discriminated for complex sounds such as bands of noise (Mossop and Culling, 1998). Although our stimuli had a smaller bandwidth than those of Mossop and Culling, the subjects in our experiment reported that stimuli with large values of ITDENV were lateralized toward the leading side. A two-down, one-up adaptive procedure was used (Levitt, 1971), and feedback was given after each trial. Following two consecutive correct responses, the ITD was divided by a factor k and following an incorrect response, the ITD was multiplied by k. Before the first turnpoint, k was equal to 1.253, between the first and second turnpoints k was equal to 1.252, and subsequently k was equal to 1.25. A run ended after eight turnpoints. The threshold corresponding to the 71% correct point on the psychometric function was taken as the geometric mean of the values of the ITD at the last six turnpoints. Three threshold estimates were obtained for each condition and each subject, and the geometric mean of the three was taken as the final estimate.

The order of testing the different conditions was pseudo-random and different for each subject. The experiment was conducted in a double-blind manner; neither the subject nor the person testing the subject knew the order of testing of the different conditions. Test sessions lasted 1.5–2 h, including breaks, and each subject was tested in two sessions.

C. Results and discussion

Initial analyses showed no significant correlations between the threshold values of the ITD (ITDTFS, ITDENV, and ITDTFS/ENV) and the pure-tone average threshold at low frequencies (250 and 500 Hz) or the pure-tone average threshold at high frequencies (1000–8000 Hz; all r values in the range −0.33–0.17, all p > 0.1). This is not surprising given that all subjects had audiometric thresholds ≤20 dB HL at 250 and 500 Hz and previous research has shown no correlation between ITDTFS discrimination of low-frequency sounds and audiometric thresholds at high frequencies (Moore et al., 2012a; Füllgrabe and Moore, 2017). However, ITD discrimination did tend to be worse for the older group than for the young group. Hence, in what follows we present the results separately for the young and older groups, ignoring any differences in audiometric threshold at high frequencies.

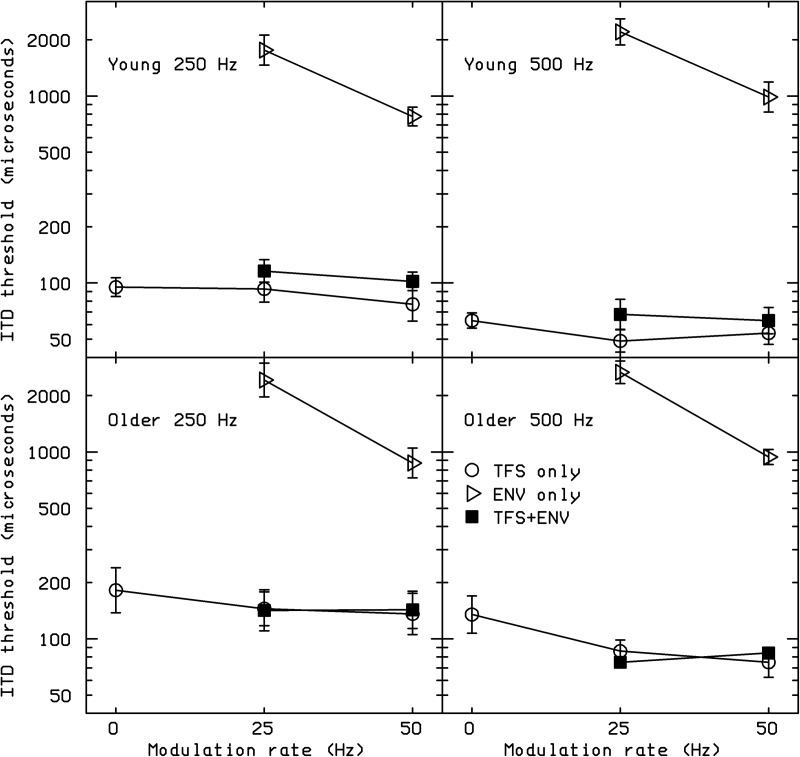

Figure 2 shows the geometric mean ITD thresholds for the two groups. The data were analyzed using two analyses of variance (ANOVAs), both based on the logarithms of the thresholds, as the variability of the thresholds was roughly constant across conditions when expressed in this way. ANOVA 1 was based on the ITDTFS thresholds (open circles) and used a mixed design with between-subjects factor of age group (young or older) and within-subject factors of carrier frequency (250 or 500 Hz) and AM rate (0, 25, or 50 Hz). ANOVA 2 was based on all data obtained using the AM rates of 25 and 50 Hz. This also used a mixed design with between-subjects factor of age group and within-subject factors of carrier frequency (250 or 500 Hz), AM rate (25 or 50 Hz), and type of ITD (TFS, ENV, or TFS/ENV). For both ANOVAs, Mauchley's test showed that the condition of sphericity was satisfied. The results of the ANOVAs are given together with the descriptions of the results. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Fisher's protected LSD test (Keppel, 1991).

FIG. 2.

Results of experiment 1 showing thresholds (μs) for detecting changes in ITD relative to an ITD of 0 in the following conditions: ITD in the TFS of pure tones (leftmost open circle in each panel), with synchronous envelopes at the two ears; ITD in the TFS of AM tones with AM rates of 25 and 50 Hz with synchronous envelopes at the two ears (middle and right open circles in each panel); ITD in the ENV of AM tones with in-phase TFS at the two ears (open triangles); and ITD in both TFS and ENV (filled squares). The left and right panels are for carrier frequencies of 250 and 500 Hz, respectively. The upper and lower panels are for young and older subjects, respectively. The error bars show ±1 standard error.

ANOVA 1 gave a significant effect of age [F(1,21) = 6.0, p = 0.023]; ITDTFS thresholds were higher for the older than for the young group. There was no significant interaction of age with AM rate or carrier frequency. The mean thresholds for detecting changes in ITDTFS for the unmodulated pure tone (leftmost open circles, plotted at a modulation rate of 0) at 250 and 500 Hz, respectively, were 95 and 63 μs for the young subjects and 182 and 135 μs for the older subjects. The geometric mean across all ITDTFS thresholds was 70 μs for the young subjects and 121 μs for the older subjects.

ANOVA 1 also gave a significant effect of AM rate [F(2,42) = 8.17, p = 0.001]. The thresholds for detecting changes in ITDTFS for the AM tones (middle and rightmost open circles) were somewhat lower than for the pure tones, for both groups; mean thresholds were 109, 86, and 80 μs for the AM rates of 0, 25, and 50 Hz, respectively. Post hoc tests showed that thresholds did not differ significantly for the 25- and 50-Hz rates, but thresholds for both of these rates were significantly lower than for the 0-Hz rate (both p < 0.02). Thus, the presence of AM improved ITDTFS discrimination, even though the AM itself was uninformative (ITDENV = 0 in all intervals) and even though ITDENV thresholds were much higher than ITDTFS thresholds. This may be connected with the finding that ITDTFS information is used most effectively during the portions of AM stimuli where the envelope is rising (Dietz et al., 2013b; Dietz et al., 2014; Moore et al., 2016). Such rising portions occur only at the onsets of steady tones, but occur repeatedly during the presentation of AM tones.

There was a significant effect of carrier frequency [F(1,21) = 54.26, p < 0.001], mean thresholds being higher at 250 than at 500 Hz. For the pure-tone stimuli, this is consistent with results in the literature, suggesting that the ITDTFS threshold at low frequencies is approximately constant when expressed as the IPD (Yost, 1974). For the 25-Hz AM rate, the mean thresholds for detecting changes in ITDTFS at 250 and 500 Hz, respectively, were about 93 and 49 μs for the young subjects, and 145 and 86 μs for the older subjects. For the 50-Hz AM rate, the mean thresholds for detecting changes in ITDTFS at 250 and 500 Hz, respectively, were about 77 and 54 μs for the young subjects, and 136 and 75 μs for the older subjects. The effects of carrier frequency for the AM stimuli are again consistent with the idea that the threshold corresponds to a constant IPD (Yost, 1974; Dietz et al., 2013a).

ANOVA 2 showed no significant main effect of age. The geometric mean thresholds for TFSENV differed only slightly for the young and older groups (1312 and 1517 μs, respectively), while the thresholds for ITDTFS and ITDTFS/ENV tended to be lower for the young than for the older group (66 versus 106 μs, respectively, for ITDTFS and 84 versus 106 μs, respectively, for ITDTFS/ENV). However, the interaction of age and type of ITD did not reach significance: [F(2,42) = 2.63, p = 0.084]. There was a significant effect of type of ITD [F(2,42) = 914.2, p < 0.001]. The geometric mean threshold for detecting changes in ITDENV (1407 μs, open triangles) was much higher (p < 0.001) than the mean thresholds for detecting changes in ITDTFS or ITDTFS/ENV (83 and 94 μs), which did not differ significantly. There was a significant effect of AM rate [F(1,21) = 71.4, p < 0.001], the mean threshold being higher for the 25- than for the 50-Hz rate. This is consistent with data in the literature (Dietz et al., 2013a). There was a significant interaction of AM rate and type of ITD [F(2,42) = 63.1, p < 0.001]. For ITDENV, post hoc tests showed that the thresholds were higher for the 25- than for the 50-Hz AM rate for both carrier frequencies and both groups (all p < 0.01). For ITDTFS and ITDTFS/ENV, the AM rate had no significant effect. There was no significant interaction between AM rate and age. There was a significant effect of carrier frequency [F(1,21) = 25.3, p < 0.001] thresholds being lower for the higher carrier frequency. There was no significant interaction between carrier frequency and age.

The addition of ITDENV cues to ITDTFS cues (filled squares compared to open circles) had little effect for the older group and tended to impair performance for the young group. However, post hoc tests showed that there was no significant difference between ITDTFS and ITDTFS/ENV thresholds for either group (p > 0.05). The lack of benefit of ENV cues is not surprising, as the magnitude of ITDENV in the combined-cue condition was 1–2 orders of magnitude below the ITDENV detection threshold.

III. EXPERIMENT 2

A. Rationale

The questions addressed by this experiment were the following: (1) Are binaural TFS and ENV cues processed independently? (2) Is the processing and relative weighting of combinations of binaural TFS and ENV cues affected by age? To answer these questions, we used a design similar to that employed by Furukawa (2008) to assess whether ITD cues and interaural intensity difference (IID) cues are processed independently. He measured the detectability indices, d′, for ITD and IID changes, imposed individually or simultaneously in a consistent direction. Comparison of d′ values for the combined cues with d′ values for the individual cues suggested that ITD and ILD cues are not processed completely independently. The interaction in the processing of the two cues was stronger for high frequencies than for low frequencies.

In the first stage of our experiment, we estimated, for each subject, pairs of values of ITDTFS and ITDENV that would be equally discriminable (giving 71% correct in the 2-AFC task that was used) when each was presented alone. As would be expected from the results of experiment 1, the values of ITDENV determined in this way were much larger than the values of ITDTFS. Then, those equally discriminable pairs of values were presented in combination, either in a consistent direction (e.g., both leading at the left) or in an inconsistent direction (e.g., ITDTFS leading at the left and ITDENV leading at the right). If binaural TFS and ENV cues are not processed independently, and both determine perceived lateral position, then in the inconsistent condition the cues might partly or completely cancel, leading to relatively poor performance, although discrimination based on decorrelation or diffuseness of the image might still be possible (Dietz et al., 2012). If the cues are processed independently, then they should not cancel in the inconsistent condition, and performance should remain well above chance. Dietz et al. (2009) showed that an ITDTFS could be traded with an opposing ITDENV to produce a centered image, but the value of ITDENV required to do this was a non-monotonic function of ITDTFS. Generally, values of ITDTFS corresponding to an IPD of about 45° required the largest opposed ITDENV. The results of Dietz et al. (2009) suggest that for a given ITDENV, there may be two ITDTFS values that lead to a (nearly) centered image, implying incomplete cancellation of ITDENV and ITDTFS.

B. Method

1. Subjects

A subset of the subjects from experiment 1, together with one new subject, served as subjects in experiment 2. The new subject was 20 yr old and had normal hearing at low frequencies but impaired hearing at high frequencies. There were six young and seven older subjects (ages are shown in Table I and Fig. 3). Across both age groups, eight had normal hearing at high frequencies (thresholds ≤20 dB HL for all audiometric frequencies up to 8000 Hz) and five had high-frequency hearing loss.

TABLE I.

Thresholds estimated in stage 1 of experiment 2 for each subject. The age of each subject is also given.

| Carrier = 250 Hz | Carrier = 500 Hz | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | Age (yr) | ITDTFS (μs) | ITDENV (μs) | ITDTFS (μs) | ITDENV (μs) |

| 1 | 20 | 111 | 1220 | 62 | 1120 |

| 2 | 20 | 98 | 702 | 78 | 1167 |

| 3 | 20 | 71 | 499 | 56 | 668 |

| 4 | 20 | 77 | 437 | 63 | 398 |

| 5 | 21 | 83 | 719 | 55 | 1438 |

| 6 | 22 | 41 | 500 | 28 | 973 |

| 7 | 62 | 145 | 1179 | 90 | 947 |

| 8 | 68 | 144 | 995 | 112 | 846 |

| 9 | 69 | 304 | 3601 | 133 | 1468 |

| 10 | 70 | 152 | 1203 | 80 | 1467 |

| 11 | 71 | 108 | 732 | 84 | 914 |

| 12 | 73 | 73 | 486 | 63 | 530 |

| 13 | 78 | 56 | 740 | 40 | 638 |

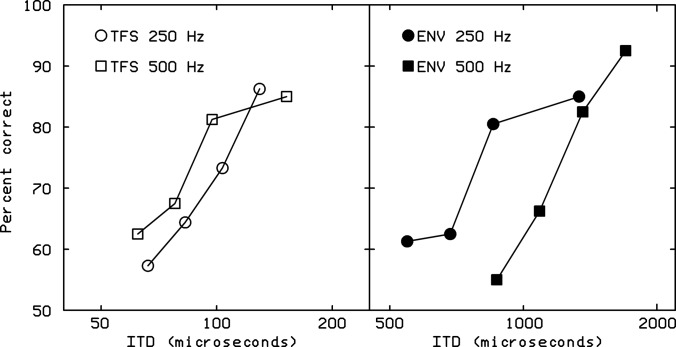

FIG. 3.

Psychometric functions for the detection of ITDTFS alone (left) and ITDENV alone (right) for a typical 20-yr-old subject with normal hearing at all frequencies. Circles and squares show results for the 250- and 500-Hz carriers, respectively.

2. Stimuli and procedure

The stimuli were similar to the AM stimuli used in experiment 1, except that only the modulation rate of 50 Hz was used. In stage one of the experiment, psychometric functions for the discrimination of an ITD of τ from an ITD of 0 were determined separately for ITDTFS and ITDENV. This was done to give more precise estimates of the ITD leading to 71% correct than were obtained using the adaptive procedure of experiment 1. For each type of cue, three to five values of the ITD were chosen, spaced around the threshold estimated in experiment 1. For each type of cue, and each ITD, performance was measured in at least three blocks of 40 trials. The order of cue type and ITD value was random. The mean percent correct across the blocks for each ITD and cue type was used to estimate the psychometric functions, and the ITD required for 71% correct was determined by interpolation. This took between two and three sessions, each lasting 1.5–2 h, including breaks.

In stage two of the experiment, the pairs of equally detectable values of ITDTFS and ITDENV were presented in combination, either in a consistent direction or in an inconsistent direction. In the consistent condition, the ITD in both the envelope and the TFS of the target stimuli led at the right ear. In the inconsistent condition, the envelope of the target stimuli was delayed at the left ear, while the TFS was delayed at the right ear. The percentage correct performance was measured in 3 blocks of 40 trials for each direction. This took about one two-hour session. As for experiment 1, the experimenter and subject were blind to the condition being tested.

C. Results

Figure 3 shows typical psychometric functions for the detection of ITDTFS alone (left) and ITDENV alone (right) for a 20-yr-old subject with normal hearing at all frequencies (subject 2 in Table I). The psychometric functions for all subjects always included at least one ITD leading to more than 71% correct and one ITD leading to less than 71% correct. To estimate the reliability of the estimates of the ITD giving 71% correct (the “thresholds”), we split the data for each subject and condition into 2 halves (giving at least 60 trials for each ITD used) and estimated the threshold separately from the psychometric functions for each half. The two estimates for a given subject and condition typically differed by a factor of less than 1.1 (85% of cases) and never differed by more than a factor of 1.4. Therefore, we think that the threshold based on all of the data for a given subject and condition typically differs from the “true” threshold by a factor less than 1.1. Table I shows the estimated thresholds for each subject in each condition. Given the typical slopes of the psychometric functions, these thresholds would lead to percent-correct values within about ±5% of the target value of 71% correct.

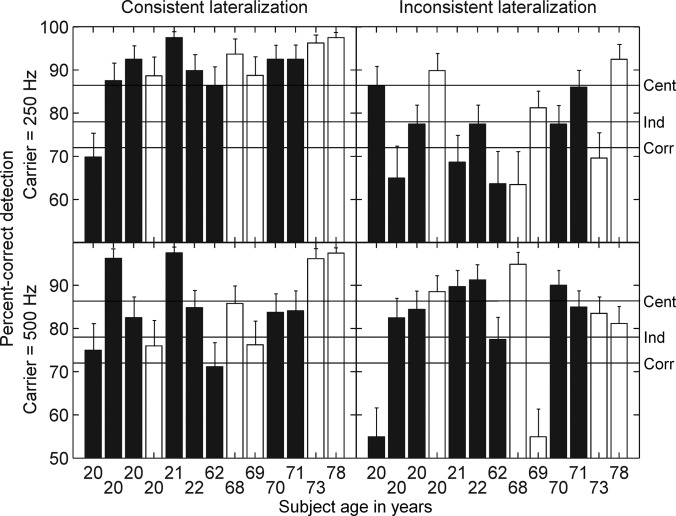

The results for stage 2 of experiment 1 are shown in Fig. 4. The left and right panels show results for the consistent and inconsistent conditions, respectively. Error bars indicate the upper end of the 90% confidence interval around the mean based on the 120 trials that were obtained for each condition, calculated using the “Wilson” method described by Brown et al. (2001); the 90% confidence interval is roughly symmetrical about the mean over most of the range shown in Fig. 4. The top and bottom panels show results for the 250- and 500-Hz carriers, respectively. Within each panel, the subjects are ordered by age from left to right; age is indicated at the bottom. Black bars indicate subjects with normal hearing at high frequencies, and open bars indicate subjects with hearing loss at high frequencies. Table II shows mean scores (with SDs in parentheses) for each condition with the subjects grouped by hearing status at high frequencies. There was no clear effect of high-frequency hearing loss. Table III shows mean scores (SDs) for each condition with the subjects grouped by age. There was also no clear effect of age. There were, however, substantial individual differences.

FIG. 4.

Percent correct scores for each subject for the conditions in which equally detectable ITDs in TFS and ENV (71% correct, d′ = 0.78) were combined either in a consistent manner (left panels) or an inconsistent manner (right panels). Error bars indicate the upper end of the 90% confidence interval around the mean. Subjects are ordered by age from left to right, and their data are presented in the same order as for Table I. Black bars and open bars indicate, respectively, subjects with normal hearing and subjects with high-frequency hearing loss but normal hearing at the test frequencies of 250 Hz (top) and 500 Hz (bottom). The lowest horizontal line in each panel shows the score that would be obtained if the internal noise that limited performance was highly correlated for ITDTFS and ITDENV, or if only one of the two cues was used (model Corr). The middle horizontal line shows the score that would be obtained if the internal noise that limited the use of ITDTFS and ITDENV was independent for the two cues and evidence from the two cues was combined optimally (model Ind). The top horizontal line shows the score that would be obtained if the internal noise that limited performance occurred after information from the two cues had been combined (model Cent). Scores falling above this line indicate super-additivity.

TABLE II.

Mean percent correct scores (SDs) for stage 2 of experiment 2 for subjects grouped by high-frequency hearing status: normal or impaired at high frequencies.

| Condition | Consistent | Inconsistent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Impaired | Normal | Impaired | |

| Carrier = 250 Hz | 89 (8) | 93 (4) | 76 (9) | 80 (13) |

| Carrier = 500 Hz | 85 (9) | 87 (11) | 82 (12) | 81 (15) |

TABLE III.

Mean percent correct scores (SDs) for stage 2 of experiment 2 for subjects grouped by age.

| Condition | Consistent | Inconsistent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young | Older | Young | Older | |

| Carrier = 250 Hz | 88 (9) | 93 (4) | 78 (10) | 77 (11) |

| Carrier = 500 Hz | 86 (10) | 85 (10) | 82 (14) | 81 (13) |

We next compare the performance that was measured for the two conditions with combined cues (consistent and inconsistent) with that predicted by signal detection theory (Macmillan and Creelman, 2005) under various assumptions. Note that all of the analyses presented in the rest of this section are based on the assumption that performance in a condition where only one type of cue is informative (ITDTFS or ITDENV) reflects only the influence of the informative cue. For example, performance in condition ITDENV is assumed to depend only on the magnitude of the ITD in the envelope, and is unaffected by the uninformative ITD of 0 in the TFS. It will be argued later that this assumption may not be correct. However, for the moment, we consider predictions based on this assumption.

If performance with each of the two cues presented in isolation is mainly limited by independent internal noises, i.e., the two cues are coded independently, and if information is combined optimally across the two cues, then the d′ value for the combined conditions, d′TFS/ENV, should be

| (1) |

where and are the d′ values for each cue when presented alone, which were both selected to be 0.78. Hence, under this assumption, = 1.1, corresponding to 78% correct in a 2-AFC task. This percent correct is indicated by the middle horizontal line in each panel of Fig. 4. We refer to this model as Ind (for independent noise sources).

If the two cues are not coded independently, so that the internal noise that limits performance is partly correlated for the two cues, then is predicted to be

| (2) |

where r is the correlation between the two internal noises that limit performance for the two cues (r < 1; Gockel et al., 2010). In this case, the predicted value of is less than 1.1 and the predicted percent correct is below 78%. For example, if the internal noises are highly correlated, with r = 0.99, then the predicted value of is 0.78, the same as for the presentation of each cue in isolation. The corresponding percent correct of 71% is indicated by the bottom horizontal line in each panel of Fig. 4. We refer to this model as Corr (for correlated noise sources).

Finally, if performance is almost entirely limited by a central noise that occurs after information from the two cues has been combined, and if information is combined optimally across the two cues, then is predicted to be

| (3) |

In this case, = 1.56, corresponding to 86.5% in a 2-AFC task. This percent correct is indicated by the top horizontal line in each panel of Fig. 4. We refer to this model as Cent (for central noise).

Consider first the results for the consistent condition. For the 250-Hz carrier, 12 out of 13 subjects gave scores that were well above the middle line, corresponding to the optimal combination of information from cues whose use is limited by independent internal noises [Ind, Eq. (1)]. Remarkably, for 11 subjects scores were above the top line, which indicates the performance that would be expected if the main source of internal noise were added after information from the 2 cues was combined [Cent, Eq. (3)]. We refer to this unexpectedly good performance as “super-additivity.” One young subject gave a score of 70%, close to the score of 71% that would be expected if only one of the cues were used or if the internal noise limiting use of the cues were highly correlated across the two cues [Corr, Eq. (2)]. For the carrier frequency of 500 Hz, the pattern of results was more mixed. Nine subjects gave scores above 78% correct, and four gave scores well above 86.5%, indicating super-additivity. Three subjects gave scores between 71% and 78% correct, indicating some but imperfect combination of information from the two cue types, and one gave a score just below 71%. Whether or not super-additivity occurred was not clearly related to age or to whether or not there was hearing loss at high frequencies.

Consider next the results for the inconsistent condition. Here, there were very marked individual differences. Five subjects gave scores above 78% for the 250-Hz carrier and ten gave scores above 78% for the 500-Hz carrier, despite the fact that the ITDTFS and ITDENV cues would have led to perceived lateralization in opposite directions. Two subjects gave scores above 86.5% for the 250-Hz carrier and five subjects gave scores above 86.5% for the 500-Hz carrier. This is remarkable because it means that, at least for these subjects, the cues were not processed along a single perceptual dimension, such as perceived lateralization, but despite this, the internal noise limiting use of the two cues was not independent, because super-additivity occurred. For five subjects with the 250-Hz carrier and two subjects for the 500-Hz carrier, the scores were below 71% correct, suggesting that, for them, the TFS and ENV cues did partially cancel. The remaining subjects gave scores close to 78% correct, as would be expected from the optimal combination of independent sources of information. For the 250-Hz carrier, most subjects performed more poorly in the inconsistent than in the consistent condition, but for the 500-Hz carrier, this trend was not so clear.

It is noteworthy that the pattern of results could differ markedly across conditions within individual subjects. For example, in the inconsistent condition, subject 1 showed very good performance, close to that predicted by the Cent model, for the 250-Hz carrier, but showed very poor performance, below that predicted by the Corr model, for the 500-Hz carrier. Conversely, in the inconsistent condition subject 4 showed poor performance with the 250-Hz carrier and very good performance with the 500-Hz carrier. Some subjects performed better in the inconsistent condition than in the consistent condition for one carrier frequency but not the other.

The origin of the idiosyncratic effects of carrier frequency is unclear. One across-frequency difference is that for the 250-Hz carrier frequency, at which the auditory filter bandwidth is about 52 Hz (Glasberg and Moore, 1990), the sidebands might have been partially resolved for some subjects; the upper and lower sidebands are roughly equally detectable for this carrier frequency (Sek and Moore, 1994). In contrast, the sidebands would have been completely unresolved for the 500-Hz carrier. Partial resolution of the sidebands could have two effects. First, it would allow across-frequency comparisons of ITD, including the computation of “straightness” (Stern et al., 1988). Second, the partial resolution of the sidebands would reduce the effective AM depth at the carrier frequency.

D. A possible explanation for super-additivity

We next describe a possible explanation of the super-additivity that occurred for some subjects and conditions even for the 500-Hz carrier, for which the sidebands would not have been resolved. The explanation is based on the finding of experiment 1 that the ITD discrimination threshold for each cue alone was much higher for ITDENV than for ITDTFS. Assume that in our task, subjects made use of both ITDENV and ITDTFS cues, even when one of the cues was uninformative. When the ITD was present in ENV alone, the fact that ITDTFS was zero may have provided powerful evidence indicating that the sound source did not move. Hence, a very large value of ITDENV was required to reach the threshold. On the other hand, when the ITD was present in the TFS alone, the fact that ITDENV was zero may have provided only very weak evidence that the sound source did not move. Hence, the value of ITDTFS at threshold was relatively small.

In experiment 2, the values of ITDTFS and ITDENV for the combined-cue conditions were chosen so that each was equally discriminable when presented alone. Assume that, for some subjects, the perceptual decision was based on a balance between evidence that the source moved and evidence that the source did not move. Consider the hypothetical scenario illustrated in Table IV in which the relative evidence provided by each cue is indicated for each condition. These evidence values would be applicable on average for the specific values of ITDTFS and ITDENV used for a given subject. Evidence favoring the perception of movement is given a positive sign and evidence favoring the perception of no movement is given a negative sign. When the ITD is present only in the TFS, the positive evidence for movement has been assigned an arbitrary value of +1. The ENV cue (ITDENV = 0) providing evidence for no movement is assumed to be much weaker, and has been assigned a value of −0.05; the absolute value is low because the threshold is much higher for ITDENV than for ITDTFS. The net value of the evidence for movement is +0.95. When the ITD is present only in the ENV, the negative evidence for movement provided by the TFS cue has been assigned a value of −0.5. The absolute value of the evidence has been assumed to be lower than when there was positive evidence from ITDTFS, but this assumption is not crucial to the argument. In order to achieve net evidence for movement with a value of +0.95, the evidence provided by TFSENV has to have a value of +1.45, corresponding to the very large value of ITDENV needed to achieve threshold. Consider now the combined condition. The evidence from the TFS cue has a value of +1 and the evidence from the ENV cue has a value of +1.45. The net evidence for movement is now +2.45, which is higher than the sum of the evidence values for either cue alone. This could account for the super-additivity that occurred for some subjects.

TABLE IV.

Hypothetical example of how evidence for movement of AM stimuli from TFS and ENV cues may be combined for three conditions: ITD in the TFS only, ITD in ENV only, and ITD in both. When an ITD is present in the TFS or ENV it is assumed to provide positive evidence, and when the ITD is absent in the TFS or ENV it is assumed to provide negative evidence.

| Condition | Evidence from TFS | Evidence from ENV | Net evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITD in TFS only | +1.0 | −0.05 | +0.95 |

| ITD in ENV only | −0.5 | +1.45 | +0.95 |

| ITD in TFS + ENV | +1.0 | +1.45 | +2.45 |

The scenario illustrated in Table IV does not take into account whether the two cues were presented in a consistent or inconsistent manner. However, there was a trend for lower performance in the inconsistent than in the consistent condition, especially for the 250-Hz carrier. It is possible that some subjects based their decisions on perceived changes in the lateral position of the sound image. The sound image would have moved less in the inconsistent than in the consistent condition. This could explain why a few subjects scored well below 71% correct in the inconsistent condition. Other subjects may have perceived two sound images or a broader sound image in the inconsistent condition, as can occur when ITDs are traded against interaural level differences in lateralization experiments (Whitworth and Jeffress, 1961; Hafter and Jeffress, 1968). They may have based their decisions on the extent to which the two images moved relative to each other or on changes in the width of the sound image.

Overall, the results are consistent with the idea that ITDTFS and ITDENV cues are processed at least partly independently, and that, for some subjects, both cues are used to determine whether a change in lateral position occurred, even when one of the cues is uninformative.

IV. GENERAL DISCUSSION

The results of experiment 1 showed that much larger ITDs were required for discrimination of ITDENV than for discrimination of ITDTFS. The effect of age tended to be larger for ITDTFS than for ITDENV, although the interaction of age and ITD type failed to reach significance. A similar pattern of results was found in stage 1 of experiment 2 (see Table I). A significant effect of age was found for ITDTFS discrimination (ANOVA 1 of experiment 1). The geometric mean across all ITDTFS thresholds was 70 μs for the young subjects and 121 μs for the older subjects, a worsening with greater age by a factor of 1.7. The adverse effect of greater age is similar to what has been reported previously for the discrimination of ITDTFS in pure tones (Ross et al., 2007; Grose and Mamo, 2010; Moore et al., 2012a; Moore et al., 2012b; Füllgrabe and Moore, 2017). The geometric mean across TFSENV thresholds differed only slightly for the young group and the older group (1312 and 1517 μs, respectively), consistent with the results of King et al. (2014), although the effect of age on TFSENV thresholds was significant in their study but not in ours. The small effect of age on TFSENV thresholds suggests that changes in processing efficiency with age are small or nonexistent.

ITDTFS discrimination was better for the AM stimuli than for the pure-tone stimuli, despite the fact that the AM was uninformative and despite the fact that ITDENV thresholds were much higher than ITDTFS thresholds. As noted earlier, this may be connected with the finding that ITDTFS information is used most effectively during the portions of AM stimuli where the envelope is rising (Dietz et al., 2013b; Dietz et al., 2014). At first sight, this finding might appear inconsistent with the arguments illustrated in Table IV that were used to account for the super-additivity that occurred for some subjects. These arguments are based on the assumption that the ITDTFS thresholds for the AM stimuli in experiment 1 and in stage 1 of experiment 2 were negatively influenced by the non-informative ITDENV value of 0. However, we think that these findings are not inconsistent. The relatively large beneficial effect of AM on the use of TFS information depends on the presence or absence of AM. It is revealed by comparing ITDTFS thresholds for unmodulated and modulated stimuli, and it presumably reflects the existence of multiple signal segments with rising amplitude when the AM is present. When ITDTFS thresholds were measured in the presence of non-informative AM in experiment 1 and stage 1 of experiment 2, AM was present in all stimuli, so the beneficial effect of the AM was always present. This does not preclude a small negative effect of non-informative AM (ITDENV = 0) relative to the case where ITDENV is large enough to be detectable (as in stage 2 of experiment 2).

The results of experiment 2 showed large individual differences, which may well reflect the use of different cues. Some subjects may have based their decisions largely on the lateral position of the sound image. Other subjects may have used a cue of image width or diffuseness. It is known that there are large individual differences in sensitivity to such cues (Spencer et al., 2016). The good performance obtained in the inconsistent condition for some subjects contradicts the idea that ITDTFS and ITDENV cues are mapped onto a single lateralization-based perceptual dimension, performance being limited by noise added after the mapping.

V. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Sensitivity to changes in ITD in the ENV and TFS of AM tones was assessed for young and older subjects, all with normal hearing at the carrier frequencies of 250 and 500 Hz. Some subjects had hearing loss at higher frequencies. In experiment 1 thresholds for detecting changes in ITD (relative to an ITD of 0) were measured when the ITD was present in the TFS alone (ITDTFS), the envelope alone (ITDENV), or both (ITDTFS/ENV). Mean thresholds were higher for the older than for the young subjects, especially for ITDTFS. Thresholds were not correlated with audiometric thresholds at the test frequencies or at higher frequencies. ITDENV thresholds were much higher than ITDTFS thresholds, while ITDTFS/ENV thresholds were similar to ITDTFS thresholds. ITDTFS thresholds were lower than ITD thresholds obtained with an unmodulated pure tone, indicating that uninformative AM can improve ITDTFS discrimination. This may happen because ITDTFS cues are used more effectively during rising portions of the envelope of AM stimuli (Dietz et al., 2013b; Dietz et al., 2014).

In experiment 2, equally detectable values of ITDTFS and ITDENV were combined so as to give consistent or inconsistent lateralization. There were large individual differences, and these were unrelated to age or to the presence/absence of hearing loss at high frequencies. Several subjects gave scores that were much higher than would be expected from the optimal combination of independent sources of information, even for the inconsistent condition. Indeed, some subjects gave scores that were better than would be predicted if the internal noise that limited performance occurred after information from the two cues had been combined. We refer to this as super-additivity. Although performance was generally worse in the inconsistent than in the consistent condition, some subjects showed super-additivity even for the latter.

It is suggested that ITDTFS and ITDENV cues can be processed at least somewhat independently, but that both cues may influence judgments even when one cue is uninformative (i.e., the ITD in one cue has a fixed value of 0). When either ITDTFS or ITDENV is 0, this is assumed to contribute negative evidence for a change in lateral position. A simple model based on the combination of positive and negative evidence was able to account qualitatively for the super-additivity observed for some subjects. The individual differences may be related to whether subjects base their judgments on the lateral position of a single sound image derived from both ENV and ITD cues, or whether they base judgments on changes in the width of the sound image or the relative movement of more than one image.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Rosetrees Trust (A.C.L., M.G.H., and B.C.J.M.), the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health of the United States (NIH/NIDCD) Grant No. R01-DC000117 (A.C.L. and L.D.B.), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Grant No. RG78536 (B.C.J.M.), and Purdue University (M.G.H.). We thank Brian Glasberg for help with statistical analyses, Dustin Dopsa for gathering some of the data, and Tom Baer, Christian Füllgrabe, Mathias Dietz, and two reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

References

- 1. Bernstein, L. R. , and Trahiotis, C. (2002). “Enhancing sensitivity to interaural delays at high frequencies by using ‘transposed stimuli,’” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 112, 1026–1036. 10.1121/1.1497620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blauert, J. (1972). “On the lag of lateralization caused by interaural time and intensity differences,” Audiology 11, 265–270. 10.3109/00206097209072591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blodgett, H. C. , Wilbanks, W. A. , and Jeffress, L. A. (1956). “Effect of large interaural time differences upon the judgment of sidedness,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 639–643. 10.1121/1.1908430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brown, L. D. , Cat, T. T. , and DasGupta, A. (2001). “Interval estimation for a proportion,” Stat. Sci. 16, 101–133. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brughera, A. , Dunai, L. , and Hartmann, W. M. (2013). “Human interaural time difference thresholds for sine tones: The high-frequency limit,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133, 2839–2855. 10.1121/1.4795778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dietz, M. , Bernstein, L. R. , Trahiotis, C. , Ewert, S. D. , and Hohmann, V. (2013a). “The effect of overall level on sensitivity to interaural differences of time and level at high frequencies,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 134, 494–502. 10.1121/1.4807827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dietz, M. , Ewert, S. D. , and Hohmann, V. (2009). “Lateralization of stimuli with independent fine-structure and envelope-based temporal disparities,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 1622–1635. 10.1121/1.3076045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dietz, M. , Ewert, S. D. , and Hohmann, V. (2012). “Lateralization based on interaural differences in the second-order amplitude modulator,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 131, 398–408. 10.1121/1.3662078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dietz, M. , Marquardt, T. , Salminen, N. H. , and McAlpine, D. (2013b). “Emphasis of spatial cues in the temporal fine structure during the rising segments of amplitude-modulated sounds,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 15151–15156. 10.1073/pnas.1309712110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dietz, M. , Marquardt, T. , Stange, A. , Pecka, M. , Grothe, B. , and McAlpine, D. (2014). “Emphasis of spatial cues in the temporal fine structure during the rising segments of amplitude-modulated sounds II: Single-neuron recordings,” J. Neurophysiol. 111, 1973–1985. 10.1152/jn.00681.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Füllgrabe, C. (2013). “Age-dependent changes in temporal-fine-structure processing in the absence of peripheral hearing loss,” Am. J. Audiol. 22, 313–315. 10.1044/1059-0889(2013/12-0070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Füllgrabe, C. , Harland, A. J. , Sek, A. P. , and Moore, B. C. J. (2017). “Development of a method for determining binaural sensitivity to temporal fine structure,” Int. J. Audiol. 56, 926–935. 10.1080/14992027.2017.1366078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Füllgrabe, C. , and Moore, B. C. J. (2017). “Evaluation of a method for determining binaural sensitivity to temporal fine structure (TFS-AF test) for older listeners with normal and impaired low-frequency hearing,” Trends Hear. 21, 233121651773723. 10.1177/2331216517737230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Füllgrabe, C. , Moore, B. C. J. , and Stone, M. A. (2015). “Age-group differences in speech identification despite matched audiometrically normal hearing: Contributions from auditory temporal processing and cognition,” Front. Aging Neurosci. 6, 347. 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Furukawa, S. (2008). “Detection of combined changes in interaural time and intensity differences: Segregated mechanisms in cue type and in operating frequency range?,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123, 1602–1617. 10.1121/1.2835226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glasberg, B. R. , and Moore, B. C. J. (1990). “Derivation of auditory filter shapes from notched-noise data,” Hear. Res. 47, 103–138. 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90170-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gockel, H. E. , Carlyon, R. P. , and Plack, C. J. (2010). “Combining information across frequency regions in fundamental frequency discrimination,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 127, 2466–2478. 10.1121/1.3327811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grose, J. H. , and Mamo, S. K. (2010). “Processing of temporal fine structure as a function of age,” Ear Hear. 31, 755–760. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181e627e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hafter, E. R. , and Jeffress, L. A. (1968). “Two-image lateralization of tones and clicks,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 44, 563–569. 10.1121/1.1911121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heinz, M. G. , and Swaminathan, J. (2009). “Quantifying envelope and fine-structure coding in auditory-nerve responses to chimaeric speech,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 10, 407–423. 10.1007/s10162-009-0169-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henning, G. B. (1974). “Detectability of interaural delay in high-frequency complex waveforms,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 55, 84–90. 10.1121/1.1928135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hopkins, K. , and Moore, B. C. J. (2010). “Development of a fast method for measuring sensitivity to temporal fine structure information at low frequencies,” Int. J. Audiol. 49, 940–946. 10.3109/14992027.2010.512613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hughes, J. W. (1940). “The upper frequency limit for the binaural localization of a pure tone by phase difference,” Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 128, 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joris, P. X. , Louage, D. H. , Cardoen, L. , and van der Heijden, M. (2006). “Correlation index: A new metric to quantify temporal coding,” Hear. Res. 216-217, 19–30. 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keppel, G. (1991). Design and Analysis: A Researcher's Handbook ( Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ: ), pp. 170–172. [Google Scholar]

- 26. King, A. , Hopkins, K. , and Plack, C. J. (2014). “The effects of age and hearing loss on interaural phase discrimination,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 135, 342–351. 10.1121/1.4838995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kunov, H. , and Abel, S. (1981). “Effects of rise/decay time on the lateralization of interaurally delayed 1-kHz tones,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 69, 769–773. 10.1121/1.385577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Levitt, H. (1971). “Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 49, 467–477. 10.1121/1.1912375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macmillan, N. A. , and Creelman, C. D. (2005). Detection Theory: A User's Guide, 2nd ed. ( Erlbaum, New York: ), pp. 1–492. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Monaghan, J. J. , Bleeck, S. , and McAlpine, D. (2015). “Sensitivity to envelope interaural time differences at high modulation rates,” Trends Hear. 19, 233121651561933. 10.1177/2331216515619331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moore, B. C. J. (2014). Auditory Processing of Temporal Fine Structure: Effects of Age and Hearing Loss ( World Scientific, Singapore: ), pp. 1–182. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moore, B. C. J. (2016). “Effects of age and hearing loss on the processing of auditory temporal fine structure,” Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 894, 1–8. 10.1007/978-3-319-25474-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Moore, B. C. J. , Glasberg, B. R. , Stoev, M. , Füllgrabe, C. , and Hopkins, K. (2012a). “The influence of age and high-frequency hearing loss on sensitivity to temporal fine structure at low frequencies,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 131, 1003–1006. 10.1121/1.3672808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moore, B. C. J. , Kolarik, A. , Stone, M. A. , and Lee, Y.-W. (2016). “Evaluation of a method for enhancing interaural level differences at low frequencies,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 140, 2817–2828. 10.1121/1.4965299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moore, B. C. J. , Vickers, D. A. , and Mehta, A. (2012b). “The effects of age on temporal fine structure sensitivity in monaural and binaural conditions,” Int. J. Audiol. 51, 715–721. 10.3109/14992027.2012.690079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mossop, J. E. , and Culling, J. F. (1998). “Lateralization of large interaural delays,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 104, 1574–1579. 10.1121/1.424369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rose, J. E. , Brugge, J. F. , Anderson, D. J. , and Hind, J. E. (1967). “Phase-locked response to low-frequency tones in single auditory nerve fibers of the squirrel monkey,” J. Neurophysiol. 30, 769–793. 10.1152/jn.1967.30.4.769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ross, B. , Fujioka, T. , Tremblay, K. L. , and Picton, T. W. (2007). “Aging in binaural hearing begins in mid-life: Evidence from cortical auditory-evoked responses to changes in interaural phase,” J. Neurosci. 27, 11172–11178. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1813-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sek, A. , and Moore, B. C. J. (1994). “The critical modulation frequency and its relationship to auditory filtering at low frequencies,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 95, 2606–2615. 10.1121/1.409831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sek, A. , and Moore, B. C. J. (2012). “Implementation of two tests for measuring sensitivity to temporal fine structure,” Int. J. Audiol. 51, 58–63. 10.3109/14992027.2011.605808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Spencer, N. J. , Hawley, M. L. , and Colburn, H. S. (2016). “Relating interaural difference sensitivities for several parameters measured in normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 140, 1783–1799. 10.1121/1.4962444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stern, R. M. , Zeiberg, A. S. , and Trahiotis, C. (1988). “Laterlization of complex binaural stimuli: A weighted image model,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 84, 156–165. 10.1121/1.396982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Whitworth, R. H. , and Jeffress, L. A. (1961). “Time versus intensity in the localization of tones,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 33, 925–929. 10.1121/1.1908849 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yost, W. A. (1974). “Discrimination of interaural phase differences,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 55, 1299–1303. 10.1121/1.1914701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]