Abstract

Purpose

To report two cases with late post-operative Candida albicans interface keratitis and endophthalmitis after Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty (DSAEK) with corneal grafts originating from a single donor with history of presumed pulmonary candidiasis.

Methods

Two patients underwent uncomplicated DSAEK by two corneal surgeons at different surgery centers but with tissue from the same donor and were referred to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute with multifocal infiltrates at the graft-host cornea interface 6 to 8 weeks later and anterior chamber cultures positive for the same genetic strain of C. albicans. Immediate explantation of the DSAEK lenticules and daily intracameral and instrastromal voriconazole and amphotericin injections failed to control the infection. Thus, both patients underwent therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty with intraocular lens explantation, pars plana vitrectomy, and serial post-operative intraocular antifungal injections.

Results

Both patients are doing well at 2 years post-operatively with best corrected vision of 20/20 and 20/30+ with rigid gas permeable lenses. One patient required a repeat optical penetrating keratoplasty and glaucoma tube implantation one year after the original surgery. Literature review reveals that donor lenticule explantation and intraocular antifungals are often inadequate to control fungal interface keratitis and a therapeutic graft is commonly needed.

Conclusions

Interface fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis due to infected donor corneal tissue is difficult to treat and both recipients of grafts originating from the same donor are at risk of developing this challenging condition.

Keywords: DSEK, Candida albicans, fungal interface keratitis, eye bank, intrastromal voriconazole injection

Introduction

Interface fungal keratitis and endophthalmitis is a rare, yet difficult to manage, complication of all types of lamellar keratoplasty. It typically presents in the late post-operative period as one or multiple infiltrates at the graft-host cornea interface in the deep stroma. This interface provides a unique sheltered environment for the development of infections and makes them particularly difficult to treat. The organisms are shielded in the interface from the normal anterior chamber immune defenses and from topical antifungals, which are notorious for their poor penetration in the deep corneal stroma.1 It is thought that the causative fungus (Candida species in the majority of the cases) is introduced intra-operatively and it comes either from the host flora or from the donor tissue.2 Herein, we report two patients who developed Candida interface keratitis and endophthalmitis after Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK) with lenticules from the same donor.

Report of Cases

Case 1

An 81 year-old man underwent uncomplicated DSAEK for pseudophakic bullous keratopathy 6 weeks prior to presentation at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute. The donor rim culture was positive for C. albicans at 7 days. The patient was kept on a standard corticosteroid taper until his post-operative week 4 visit, at which time the outside surgeon noticed a few fluffy infiltrates at the graft-cornea interface. The patient was started on amphotericin B (5 mg/mL) 6 times a day and kept on prednisolone acetate 1% 4 times a day. Two weeks later, the infiltrates appeared larger and there was anterior chamber reaction, thus the patient was referred for further management.

His vision was count fingers, there was a hypopyon as well as multiple fluffy-appearing interface infiltrates. (Figure 1A) An anterior chamber culture was taken, which grew C. albicans. Corticosteroids were stopped and the patient received daily intracameral and intrastromal injections of amphotericin B (5 μg) and voriconazole (100 μg) for 2 days and was placed on hourly topical amphotericin B (5 mg/mL) and voriconazole (10 mg/mL). The clinical response was minimal, thus the donor lenticule was explanted one day later and the patient continued with daily intracameral and intrastromal antifungal injections and hourly topical antifungals. The donor lenticule also grew C. albicans sensitive to both amphotericin B and voriconazole. Three days after explantation of the donor lenticule, the stromal infiltrates were significantly worse (Figure 1B) and signs of vitritis were noted on B scan ultrasound. Thus, therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty with a large diameter graft, intraoperative cryotherapy to peripheral infiltrates, iris biopsy, intraocular lens and capsule removal, and pars plana vitrectomy with injection of intravitreal amphotericin B (5 μg) and voriconazole (100 μg) at the end of the procedure were done. The cornea and iris biopsy was positive for C. albicans and the vitreous cultures were negative.

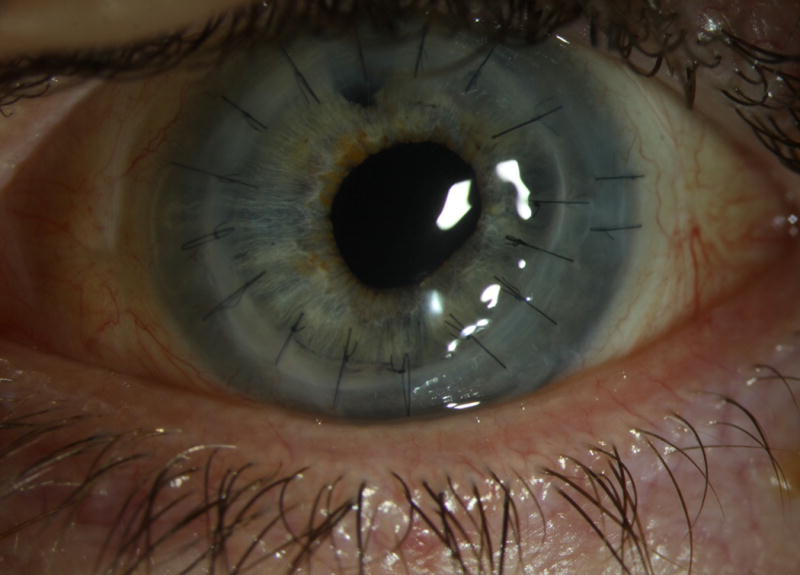

Figure 1.

Slit lamp photographs of Patient 1 with post-DSAEK Candida albicans endophthalmitis. (A) 81 year-old man with multifocal infiltrates at the graft-host cornea interface and hypopyon 6 weeks after uncomplicated DSAEK. The donor rim culture was positive for C. albicans at 7 days. (B) Three days after donor lenticule removal, intensive topical amphotericin B (5 mg/mL) and voriconazole (10 mg/mL), and daily intracameral and intrastromal injections of amphotericin B (5 μg) and voriconazole (100 μg), the infiltrates within the host cornea are significantly larger in size. The patient underwent therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty, intraocular lens and capsule removal, and pars plana vitrectomy. (C) The large therapeutic graft failed and optical penetrating keratoplasty and glaucoma tube shunt implantation were performed 6 months later. At 2 years of follow up the patient refracts to 20/30+ with a rigid gas permeable lens.

Intracameral injections of voriconazole (100 μg) were given 2–3 times per week for the first post-operative month and the patient was kept on topical amphotericin B (5 mg/mL) and voriconazole (10 mg/mL) for a total of 3 months. For the first 2 months post-operatively, a steroid-sparing immunosuppressive regimen was used with topical cyclosporine 0.05% every hour. Topical corticosteroids were then started with close follow up. The therapeutic graft failed, and an optical penetrating keratoplasty and glaucoma tube shunt implantation were performed after 6 months of clinical quiescence. His vision now (2 years later) corrects to 20/30+ with a rigid gas permeable lens. (Figure 1C)

Case 2

A 67 year-old man underwent uncomplicated DSAEK for Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy one day after Patient 1 by a different surgeon and at a different surgery center. The donor rim culture was negative, but it was only kept for 4 days in the laboratory. The patient was doing well until 6 weeks post-operatively when the outside surgeon noticed interface infiltrates. An anterior chamber culture was taken and it was positive for C. albicans. The patient was started on hourly amphotericin B (5 mg/mL) was also kept on topical corticosteroids 4 times a day. Two weeks later (i.e. at 8 weeks post-operatively), his vision was count fingers, the infiltrates were worse and a hypopyon was also noted. (Figure 2A) Thus, the patient was referred to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute for further management.

Figure 2.

Slit lamp photographs of Patient 2 with post-DSAEK Candida albicans endophthalmitis with graft originating from the same donor as Patient 1. (A) 67 year-old man with fluffy-appearing infiltrates at the graft-host cornea interface and hypopyon 8 weeks after routine DSAEK for corneal edema due to Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy. The donor rim culture was negative at 4 days and the anterior chamber culture grew the same genetic strain of C. albicans as Patient 1. Immediate donor lenticule removal and daily intracameral and intrastromal injections of amphotericin B (5 μg) and voriconazole (100 μg) failed to control the infection. A therapeutic graft, cryotherapy to the peripheral infiltrates, explantation of the intraocular lens and pars plana vitrectomy were done. (B) The graft remains clear at 2 years of follow up and the patient refracts to 20/20 with a rigid gas permeable lens.

An anterior chamber culture was done upon presentation and it was positive for C. albicans. The patient received an intracameral and intrastromal injection of amphotericin B (5 μg) and voriconazole (100 μg), topical corticosteroids were stopped, and he was placed on hourly topical amphotericin B (5 mg/mL) and voriconazole (10 mg/mL). The donor lenticule was removed and also grew C. albicans sensitive to voriconazole and amphotericin B. Despite donor lenticule explantation and daily intracameral and intrastromal antifungal injections, the patient developed worsening infiltrates within the host cornea one week post-explantation.

Therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty with a large diameter graft, intraoperative cryotherapy to peripheral infiltrates, iris biopsy, intraocular lens and capsule removal, and pars plana vitrectomy was performed with injection of intravitreal amphotericin B (5 μg) and voriconazole (100 μg) at the end of the procedure. C. albicans grew from the removed host cornea and was also seen on pathologic examination of the cornea button. The iris biopsy and vitreous cultures were negative for growth.

The patient received intracameral and intrastromal (at sites of prior peripheral infiltrates in the host) injections of amphotericin B (5 μg) and voriconazole (100 μg) 2–3 times per week for the first postoperative month. Serial anterior chamber cultures were negative post-operatively. He also used topical amphotericin B (5 mg/mL) and voriconazole (10 mg/mL) for the first 3 months as well as topical cyclosporine 0.5% four times a day. Topical corticosteroids were started at the third post-operative month (prednisolone acetate 1% 3 times/day) and the patient was followed closely for the first 6 months and remained free of recurrence. He now retains a clear graft and his vision corrects to 20/20 with a rigid gas permeable lens at 2 years of follow up. (Figure 2B)

Discussion

These two patients presented to us within 2 weeks of each other and had undergone DSAEK one day apart, yet by different surgeons and at different surgical facilities. We contacted the eye bank that supplied the grafts to the two surgeons and we were informed that both grafts originated from the same donor. The donor was a 63 year-old man who died of respiratory failure after a short hospitalization. He had chronic bronchitis and a family member reported past history of “pulmonary candidiasis”. There were no positive blood cultures during his hospitalization and no documentation of sepsis. Whole genome sequencing revealed genetically identical strains of C. albicans from the donor lenticules of both patients.

Both tissues were pre-cut at the eye bank. The death-to-preservation time was 7 hours 8 minutes and the storage media used was Optisol GS. The tissue was in storage media for 6 days (patient 2) or 7 days (patient 1) prior to transplantation. For patient 1, the post-cut endothelial cell count was 2907 and the graft tissue thickness was 111 μm. For patient 2, the post-cut endothelial cell count was 2817 and the graft tissue thickness was 119 μm. No venting incisions were used by either surgeon during surgery. For patient 1, the surgeon used a tissue folding technique to insert the tissue into the anterior chamber. For patient 2, the surgeon used the Tan injector.

In these two cases, initial treatment with topical, intracameral and intrastromal antifungals alone was not successful, nor was removal of the donor lenticule. In fact, the infection worsened after lenticule removal perhaps due to liberation of the sequestered fungi. Penetrating keratoplasty along with intraocular lens explantation, capsular bag removal, pars plana vitrectomy, and intravitreal antifungals was required to achieve control of the infection and save these eyes.

Review of all the reported cases of fungal interface keratitis shows that almost all failed topical and/or systemic antifungal therapy (Table 1. Supplemental Digital Content 1).1–14 Only 3 out of 21 reported cases of post-DSAEK fungal keratitis, resolved with intrastromal, topical and oral antifungals.1,12 Removal of the donor lenticule along with topical, intracameral and oral antifungals was performed in 9 out of 21 cases,2,5,6,8,9,14 but was successful in eradicating the infection in only 3 of those 9 eyes.8,9,14 The other 6 of those 9 eyes underwent therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty due to the presence of fungal infiltrates in the host corneal stroma after donor lenticule removal.2,5,6 Except for one case of interface keratitis due to Aspergillus fumigatus,7 all other reported cases were caused by Candida species (12 by C. albicans, 3 by C. parapsilosis, 1 by C. glabrata, and 2 by yeast identified upon confocal microscopy). Obtaining an adequate sample of a DSAEK interface infiltrate for proper microbiological testing is challenging and penetration of topical antifungals may not be sufficient to adequately treat the infection. Our review of the literature and our experience with these two cases suggest that perhaps a therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty should be performed early in cases of interface fungal keratitis due to the generally poor response to medical treatment or graft lenticule removal.

Table 1.

Review of Cases, Interventions, and Outcomes of Fungal Interface Keratitis after DSEK

| Author (Year) | Case | Indication for DSEK | Organism | Method of Organism Isolation | Donor Rim Culture | Intervention | Final Best- Corrected Vision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsui et al (2016)1 | 85 yo F | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. albicans | Culture of removed donor lenticule | C. albicans | *Removal of infected DSEK lenticule, then therapeutic PKP Topical and Intracameral Amphotericin B Oral Fluconazole Intravenous Micafungin | 20/40 |

| 71 yo F | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. glabrata | Culture of removed donor lenticule | C. glabrata | **Exchange of infected DSEK lenticule with new DSEK graft, then optical PKP Topical and Intracameral Amphotericin B Oral Fluconazole | 20/25 | |

| Tu et al (2014)2 | 66 yo M | Bullous Keratopathy | Yeast | Confocal microscopy, no culture | Negative | Intrastromal Amphotericin B Oral Fluconazole | 20/500 |

| 70 yo M | Bullous Keratopathy | Yeast | Confocal microscopy, no culture | Negative | Intrastromal and Oral Voriconazole | 20/60 | |

| Nahum et al (2014)3 | 52 yo M | Failed PK graft | C. parapsilosis | Culture of removed cornea | Negative | Therapeutic PKP Topical, Intracameral and Systemic Amphotericin & Voriconazole | 20/20 |

| 67 yo F | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. parapsilosis | Culture of removed donor lenticule | Negative | *Exchange of infected DSEK lenticule with new DSEK graft, then therapeutic PKP Topical, Intracameral and Systemic Amphotericin & Voriconazole | 20/100 | |

| 63 yo F | Failed DMEK graft | C. albicans | Culture of removed cornea | Negative | Therapeutic PKP Topical, Intracameral and Systemic Amphotericin & Voriconazole | 20/20 | |

| Villarrubia et al (2014)4 | 73 yo F | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. albicans | Culture of removed cornea | Not reported | Therapeutic PKP Topical, Intrastomal, and Intracameral Voriconazole Oral Fluconazole | Hand Motion |

| Araki- Sasaki et al (2014)5 | 72 yo M | Bullous Keratopathy | C. albicans | Culture of cornea scrapings and removed cornea | C. albicans | Therapeutic PKP IOL Removal Anterior Vitrectomy Topical Miconazole and Natamycin Topical, Intrastromal, and Oral Voriconazole | Not reported |

| Hsu et al (2014)6 | 45 yo F | Bullous Keratopathy | C. albicans | Anterior chamber paracentesis, culture of removed donor lenticule | Not performed | *Removal of infected DSEK lenticule, then therapeutic PKP, then optical PKP Pars Plana Vitrectomy Topical and Intravitreal Voriconazole Intracameral Fluconazole Oral Fluconazole | 20/100 |

| Holz et al (2012)7 | 69 yo M | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. albicans | Culture of removed donor lenticule | Not performed | *Removal of infected DSEK lenticule, then therapeutic PKP Topical and Intracameral Amphotericin & Voriconazole | 20/30 |

| 54 yo F | Bullous Keratopathy | C. albicans | Culture of removed donor lenticule | Not reported | *Removal of infected DSEK lenticule, then therapeutic PKP Topical and Intracameral Amphotericin & Voriconazole | 20/80 | |

| Sharma et al (2011)8 | 62 yo M | Bullous Keratopathy | A. fumigatus | Culture of intracameral biopsy from DSEK lenticule, Culture of removed cornea | Not reported | Oral Itraconazole Therapeutic PKP Topical Natamycin Oral Voriconazole | 20/40 |

| Ortiz- Gomariz et al (2011)9 | 76 yo F | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. albicans | Culture of aqueous and vitreous (intraoperative), Culture of removed donor lenticule | C. albicans | **Removal of infected DSEK lenticule, then optical PKP Anterior Vitrectomy Topical, Intracameral and Systemic Voriconazole# | 20/200 |

| Yamazoe et al (2011)1° | 74 yo M | Bullous Keratopathy | C. albicans | Anterior chamber paracentesis, culture of removed donor lenticule | C. albicans | **Removal of infected DSEK lenticule, then optical PKP Topical Voriconazole & Micafungin Intravitreal Miconazole Intravenous Voriconazole | 20/22 |

| Lee et al (2011)11 | 81 yo M | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. glabrata | Culture of removed cornea | Negative | Therapeutic PKP Topical and Intracameral Amphotericin Oral Fluconazole | 20/25 |

| 76 yo F | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. albicans | Cornea scrapings, Culture of removed cornea | Negative | Therapeutic PKP (suprachoroidal hemorrhage) Topical amphotericin Oral Fluconazole | Phthisis bulbi | |

| Chew et al (2010)12 | 72 yo F | Fuchs’ dystrophy | C. parapsilosis | Anterior chamber paracentesis, Vitreous tap, Culture of removed cornea | Negative | Therapeutic PKP IOL Removal Topical and Intravitreal Amphotericin & Voriconazole Oral Voriconazole | 20/40 |

| Kitzmann et al (2009)13 | 80 yo F | Failed DSEK | C. albicans | Culture of removed donor lenticule | C. albicans C. glabrata Streptococcus | **Exchange of infected DSEK lenticule with new DSEK Topical and Intracameral Amphotericin Oral Fluconazole | 20/50 |

| 80 yo F | Bullous Keratopathy | C. albicans | Cornea scrapings | C. albicans C. glabrata Streptococcus | ***Cyanoacrylate glue for perforation, then patch graft Topical and Intracameral Amphotericin | 20/40 | |

| Koenig et al (2009)14 | 80 yo F | Bullous Keratopathy | C. albicans | Culture of removed donor lenticule | C. albicans | *Removal of infected DSEK lenticule, then therapeutic PKP Topical Natamycin Oral Voriconazole | Enucleation for blind painful eye |

M, male; F, female; PKP, penetrating keratoplasty; DMEK, Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty; IOL, intraocular lens; C. albicans, Candida albicans; A. fumigatus, Aspergillus fumigatus; C. glabrata, Candida glabrata; C. parapsilosis, Candida parapsilosis

In these cases, removal of the DSEK lenticule along with topical, intracameral and oral antifungals was not curative. Fungal infiltrates were noted in the host corneal stroma after DSEK lenticule removal. Thus, therapeutic penetrating keratoplasty was performed.

In these cases, removal of the DSEK lenticule along with topical, intraocular and systemic antifungals was curative.

In this case, a 3 mm patch graft was performed at a later date, after resolution of the acute infection.

In this case, voriconazole was first given intravenously, and upon clinical improvement it was switched to orally.

We should note that in our two cases, one rim culture was positive for C. albicans whereas the other was not, but it was only kept for 4 days. Fungal organisms can take longer to grow in vitro and depending on the size of the inoculum they may not grow at all. Donor rim cultures were done in 18 of the 21 cases in the literature, they were positive in 8 of them (44%), negative in 8 of them (44%), and not reported (likely negative) in 2 (11%) of the 18 cases (Table 1. Supplemental Digital Content). The duration of the incubation of the rim culture in the microbiology laboratory is not reported. In all 8 cases with a positive rim culture, the organism that grew was identical to the one causing the interface infection (C. albicans in all 7 cases and C. glabrata in 1 case).4,9,12–14 This highlights the importance not only of performing donor rim cultures in every case, but also of keeping the culture long enough for a potentially fastidious organism to grow.

A high suspicion for a post-operative fungal interface keratitis should be maintained, especially in the setting of a positive donor rim culture. Corneal storage media in the United States are not supplemented with antifungals and a small inoculum may lead to an infiltrate in the protected environment of the graft-host interface. Moreover, small interface infiltrates may be misdiagnosed as debris and it may take weeks or months to blossom. This is due to the slow growth of fungi and the routine use of post-operative steroids. Thus, an interface infiltrate that appears several weeks after the endothelial transplantation should raise our suspicion for a fungal infection.

Finally, once a post-keratoplasty patient is diagnosed with a fungal keratitis, the recipient of the donor mate should also be followed closely. According to the most recent Eye Bank Association of America medical advisory report in 2013, if a cornea from a donor harbors a fungal burden sufficient to cause a post-keratoplasty fungal infection in a recipient eye, the other cornea from the same donor will very likely (67% of the time) cause a fungal infection in the second recipient.15 Therefore, surgeons ought to report to the supplying eye bank such post-operative complications early as they can be sight-saving for the second recipient.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Table 1 reviews all published cases of post-DSEK interface keratitis, the interventions taken and the reported outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH Center Core Grant P30EY014801, RPB Unrestricted Award and Career Development Awards, Department of Defense (DOD- Grant#W81XWH-09-1-0675), the Ronald and Alicia Lepke Grant, the Lee and Claire Hager Grant, the Jimmy and Gaye Bryan Grant, the H. Scott Huizeng Grant, the Emilyn Page and Mark Feldberg Grant, and the Richard Azar Family Grant (institutional grants). Dr. Palioura holds the 2015 “Spyros Georgaras” scholarship from the Hellenic Society of Intraocular Implant and Refractive Surgery.

Footnotes

Proprietary/Financial Interests: None

References

- 1.Tsui E, Fogel E, Hansen K, et al. Candida Interface Infections After Descemet Stripping Automated Endothelial Keratoplasty. Cornea. 2016;35:456–464. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tu EY, Hou J. Intrastromal antifungal injection with secondary lamellar interface infusion for late-onset infectious keratitis after DSAEK. Cornea. 2014;33:990–993. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahum Y, Russo C, Madi S, et al. Interface infection after descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty: outcomes of therapeutic keratoplasty. Cornea. 2014;33:893–898. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villarrubia A, Cano-Ortiz A. Candida keratitis after Descemet stripping with automated endothelial keratoplasty. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014;24:964–967. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araki-Sasaki K, Fukumoto A, Osakabe Y, et al. The clinical characteristics of fungal keratitis in eyes after Descemet’s stripping and automated endothelial keratoplasty. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1757–1760. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S67326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hsu YJ, Huang JS, Tsai JH, et al. Early-onset severe donor-related Candida keratitis after descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:874–876. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holz H, Pirouzian A. Simultaneous Interface Candida Keratitis in 2 Hosts Following Descemet Stripping Endothelial Keratoplasty With Tissue Harvested From a Single Contaminated Donor. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2012;1:250. doi: 10.1097/01.APO.0000417988.89881.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma N, Agarwal PC, Kumar CS, et al. Microbial keratitis after descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Eye Contact Lens. 2011;37:320–322. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31820e7144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortiz-Gomariz A, Higueras-Esteban A, Gutierrez-Ortega AR, et al. Late-onset Candida keratitis after Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty: clinical and confocal microscopic report. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21:498–502. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2011.6228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamazoe K, Den S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Severe donor-related Candida keratitis after Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249:1579–1582. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee WB, Foster JB, Kozarsky AM, et al. Interface fungal keratitis after endothelial keratoplasty: a clinicopathological report. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2011;42:e44–48. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20110407-01. Online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chew AC, Mehta JS, Li L, et al. Fungal endophthalmitis after descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty–a case report. Cornea. 2010;29:346–349. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181a9d0c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitzmann AS, Wagoner MD, Syed NA, et al. Donor-related Candida keratitis after Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2009;28:825–828. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31819140c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koenig SB, Wirostko WJ, Fish RI, et al. Candida keratitis after descemet stripping and automated endothelial keratoplasty. Cornea. 2009;28:471–473. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31818ad9bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aldave AJ, DeMatteo J, Glasser DB, et al. Report of the Eye Bank Association of America medical advisory board subcommittee on fungal infection after corneal transplantation. Cornea. 2013;32:149–154. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31825e83bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content 1. Table 1 reviews all published cases of post-DSEK interface keratitis, the interventions taken and the reported outcomes.