Abstract

General population exposure to methylmercury (MeHg), the most common organic mercury compound found in the environment, occurs primarily through the consumption of contaminated fish and shellfish. Due to limited studies and lack of consideration of effect modification by fish consumption, it remains uncertain if exposure to mercury affects semen parameters. Thus, we investigated whether hair Hg levels, a biomarker of mercury exposure, were associated with semen parameters among men attending an academic fertility center, and whether this relationship was modified by intake of fish.

This analysis included 129 men contributing 243 semen samples who were enrolled in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study between 2005 and 2013, and had data of hair Hg, intake of fish and semen parameters available. Hair Hg levels were assessed using a direct mercury analyzer. Intake of fish was collected using a validated food frequency questionnaire. Semen parameters were analyzed following WHO 2010 evaluation criteria. Generalized linear mixed models with random intercepts accounting for within-man correlations across semen samples were used to evaluate the association of hair Hg levels and semen parameters adjusting for age, BMI, smoking status, abstinence time and alcohol intake. Effect modification by total fish intake (≤1.68 vs. >1.68 servings/week) was tested.

The median hair Hg levels of the men was 0.72 ppm and ranged from 0.03 to 8.01 ppm; almost 30% of the men had hair Hg levels >1ppm. Hair Hg levels were positively related with sperm concentration, total sperm count, and progressive motility, after adjusting for potential confounders and became attenuated after further adjustment for fish intake. Specifically, men in the highest quartile of hair mercury levels had 50%, 46% and 31% higher sperm concentration, total sperm count and progressive motility, respectively, compared to men in the lowest quartile. These associations were stronger among men whose fish intake was above the study population median. Semen volume and normal morphology were unrelated to hair Hg levels.

These results confirmed exposure to MeHg through fish intake and showed the important role of diet when exploring the associations between heavy metals and semen parameters among men of couples seeking fertility care. Further research is needed to clarify the complex relationship between fish intake and Hg, and potential effects on male reproductive health, specifically, semen parameters.

Keywords: Hair mercury (Hg) levels, fish intake, semen parameters, fertility, male reproductive health

Introduction

Mercury (Hg) is a naturally-occurring chemical element found in the earth’s crust and exists in three different chemical forms: elemental (metallic), inorganic and organic (US-EPA 2017b). Methylmercury (MeHg), the most common organic mercury compound found in the environment, is formed when mercury combines with carbon and represents the primary source of human exposure. MeHg exposure has been linked with brain, heart, kidney, lung, and immune system damage among humans of all ages, (US-EPA 2017b). General population exposure to mercury occurs primarily through the consumption of contaminated fish and shellfish (US-EPA 2017a).

In vitro (Arabi and Heydarnejad 2007; Ernst and Lauritsen 1991; Mohamed et al. 1986; Rao 1989) and animal studies (Homma-Takeda et al. 2001; Mohamed et al. 1987; Orisakwe et al. 2001) have been shown a detrimental effect of this heavy metal on male reproductive outcomes. For example, Homma-Takeda and colleagues observed impaired spermatogenesis and decreased testosterone levels were observed in 7-week-old rats treated with Hg by subcutaneous injection at a dose of 10 ppm per day during 8 days (Homma-Takeda et al. 2001). Also, decreased sperm number and testicular weight were found in 12-week-old mice when administrated a dose of 4 ppm during the 12 weeks of life by gavage (Orisakwe et al. 2001) and adult monkeys that had blood Hg levels around 2ppm had a decreased sperm motility and sperm swimming speed, and increased abnormal sperm tail morphology (Mohamed et al. 1987).

However, despite numerous studies, whether Hg affects male reproductive health in humans (Alcser et al. 1989; Choy et al. 2002a; Dickman and Leung 1998; Keck et al. 1993; Leung et al. 2001; McGregor and Mason 1991; Meeker et al. 2008; Mendiola et al. 2011; Pizent et al. 2012; Rachootin and Olsen 1983), and specifically semen quality (Chia et al. 1992; Choy et al. 2002b; Lenters et al. 2015; Meeker et al. 2008; Mocevic et al. 2013; Rignell-Hydbom et al. 2007; Zeng et al. 2015) remains unclear. One of the reasons that could explain these discrepancies in results across studies about mercury and semen parameters is the lack of consideration of fish consumption on the relationship between Hg and semen parameters, possibly resulting in residual confounding. Intake of fish and shellfish has been previously linked to better semen quality, possibly due to the beneficial effects of long chain omega-3 fatty acids which they contain (Afeiche et al. 2014; Eslamian et al. 2012; Mendiola et al. 2009; Vujkovic et al. 2009). The objective of this study was to investigate whether Hg, measured in hair samples, was associated with semen parameters among men attending an academic fertility center, and whether this relationship was modified by intake of fish.

Methods

Study population

Study participants were male partners of couples enrolled in the Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study, an ongoing prospective cohort of couples seeking infertility treatment at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Fertility Center aimed at evaluating environmental and dietary determinants of fertility (Hauser et al. 2006). Men between the ages of 18 to 56 years and without a history of vasectomy were eligible to participate, and approximately 40% of those contacted by the research nurses were enrolled. After the study procedures were explained and all questions were answered, participants signed an informed consent form. Between 2005 and 2013, 257 men provided hair samples for the assessment of mercury. Of those, 219 men had hair mercury samples that were collected less than 5 months before and no more than 1 year after semen sample collection. This time window was chosen because hair mercury is an integrated measure of exposure during the 5 months prior to sample collection. Among these 257 men, 132 (51%) completed a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) before providing a semen sample. After excluding samples for 3 azoospermic men, the final study sample for this analysis included 129 men contributing 243 semen samples. The participant’s date of birth was collected at entry, and weight and height were measured by trained study staff. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by height (in meters) squared. The participants completed a nurse-administered questionnaire that contained additional questions on lifestyle factors, reproductive health, and medical history. The study was approved by the Human Subject Committees of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the MGH, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Mercury assessment

Hair was chosen as the preferred biomarker for Hg levels in our subjects because it reflects exposure over several months (Grandjean and Weihe 2002). The hair sample was collected after recruitment into the study. The participants were instructed to obtain the hair sample when they went for a haircut to the barber. Very short hair/bald men were not able to collect their hair samples and thus are not included in this analysis. Once we received the hair sample mailed by participants loose in an envelope, it was cleaned before analysis to remove extraneous contaminants by sonication for 15 minutes in a 1% Triton X-100 solution. After sonication, samples were rinsed with distilled deionized water and dried 5 times at 60°C for 48 hours. Total Hg in parts per million (ppm) was measured using 0.02 g of the proximal 2 cm of hair using a Direct Mercury Analyzer 80 (Milestone Inc, Monroe, CT) with a matrix matched calibration curve. Certified reference material GBW 07601 (human hair; Institute of Geophysical and Geochemical Exploration, China) containing 360 ppm mercury was used as the quality control standard. The limit of detection (LOD) for Hg was 0.01 ppm with the percentage recovery for quality control standards ranging from 90 to 110 percent. Percentage difference in duplicate sample (same time point) analysis was <10.

Diet assessment

Diet was assessed using a previously validated 131-item food frequency questionnaire [FFQ; (Rimm et al. 1992)]. Participants were asked how often, on average during the previous year, they consumed specific foods, beverages, and supplements. Nutrient contents for each item were obtained from a database based on the US Department of Agriculture nutrient database (United States Department of Agriculture & Agricultural Research Service, 2008). Assessment of fish intake using this questionnaire has been validated against prospectively collected diet records representing 1 year of a diet in a different study (Salvini et al. 1989). In that study, the de-attenuated correlation of fish intake assessed with the FFQ and the 1year average of prospectively collected dietary records was 0.66 (Salvini et al. 1989). Questions regarding fish and shellfish intake in this FFQ were designed to optimize assessment of omega-3 fatty acids without regard to mercury content of different types of fish. Fish intake was defined as the sum of dark meat fish (e.g. canned tuna, salmon), white meat fish (e.g. cod, haddock), and shellfish (e.g. shrimp scallops). We calculated the total intake of caffeine and alcohol by summing the caffeine and alcohol content for the specific items multiplied by weights proportional to the frequency of use of each item.

Semen assessment

Semen was collected on site at MGH via masturbation in a sterile plastic specimen cup following a recommended 48-hour abstinence period. Some men provided multiple semen samples because their female partners underwent more than one cycle of fertility treatment and also for further evaluation of their semen quality. 56 men (43%) provided one semen sample and 73 men (57%) provided more than one semen sample (ranging from 2 to 6 semen samples). Semen volume (mL) was measured by an andrologist using a graduated serological pipet. Sperm concentration (mil/mL) and motility (% motile) were assessed using a computer-aided semen analyzer (CASA; 10HTM-IVOS, Hamilton-Thorne Research, Beverly, MA). To measure sperm concentration and motility, 5 μl of semen from each sample was placed into a pre-warmed (37°C) and disposable Leja slides (Spectrum Technologies, CA, USA). A minimum of 200 sperm cells from at least four different fields were analyzed from each specimen. Progressively motile sperm were defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 5th edition classification and included moving actively, either linearly or in a large circle, regardless of speed (World Health Organization 2010). Total sperm count (mil/ejaculate) was calculated by multiplying sperm concentration by semen volume. Total progressive motile sperm count (mil/ejaculate) was calculated by multiplying total sperm count by progressive motility. Sperm morphology (% normal) was measured on two slides per specimen (with a minimum of 200 cells assessed per slide) with a microscope using an oil-immersion 100× objective (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Strict Kruger scoring criteria were used to classify men as having normal or below normal morphology (Kruger et al. 1988). Total morphologically normal sperm count (mil/ejaculate) was calculated by multiplying total sperm count by normal morphology. Andrologists were blinded to the participants’ hair mercury levels. For quality assurance/quality control purposes in the assessment of sperm morphology, the laboratory conducted weekly evaluation of AQC monitoring of sperm morphology smears (Fertility Solutions). Deviations from acceptable ranges of variation trigger re-evaluation and, if needed, retraining of personnel. In addition, the laboratory performed quarterly competence evaluations of all technicians and proficiency testing by an outside evaluator every six months.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and baseline reproductive characteristics of the men were presented using median ± interquartile ranges (IQRs) or percentages. Due to concern regarding potential non-linear relationships between Hg and semen parameters, hair Hg was categorized into quartiles and also in two groups according to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reference level of 1.0 ppm (US-EPA 2001). Associations between hair Hg levels, demographics, dietary and baseline reproductive characteristics were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate). Sperm concentration and the sperm counts showed non-normal distributions and were transformed using the natural log (ln) before analysis. Multivariable generalized linear mixed models with random subject effects to account for repeated semen measurements within the same man were used to estimate the association of hair Hg levels with semen parameters, modeled as continuous variables and also divided by the WHO 2010 cutoffs (World Health Organization 2010). Tests for linear trends were conducted using the hair Hg levels as an ordinal level indicator variable of each quartile, simulating a continuous variable. To allow for better interpretation of the results, population marginal means (Searle et al. 1980) are presented adjusting for all the covariates in the model (at the mean level for continuous variables and for categorical variables at a value weighted according to their frequencies).

Confounding was assessed using prior knowledge on biological relevance and descriptive statistics from our study population through the use of directed acyclic graphs (Weng et al. 2009). The variables considered as potential confounders included factors previously related to semen parameters (Rooney and Domar 2014; Sharma et al. 2013), and factors associated with Hg exposure and semen parameters in this study. Final models were adjusted for age (years), BMI (kg/m2), smoking status (ever and never smoked), abstinence time (days), and alcohol intake (gr/day). Since fish intake is a source of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and because of this nutritional property may have beneficial effects on semen quality (Attaman et al. 2012; Safarinejad 2011), we fitted an additional multivariable model further adjusted for total fish intake (servings/week) and total calorie intake (kcal/day), to minimize the possibility of residual confounding due to intake of other foods, to evaluate their independent effects. Furthermore, effect modification by total fish intake (divided by the median for our study population, ≤1.68 servings/week vs. >1.68 servings/week) was tested by adding a cross product term to the final multivariate model. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by restricting the analysis to the first two 2 semen samples per man, to reduce bias that could result if men who provided more semen samples had poorer semen quality, and thus had female partners with more fertility treatment cycles. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Participants had a median (interquartile range [IQR]) age of 36 (33, 39) years and were predominantly Caucasian (89%). The median (IQR) BMI of the men was 27 (24, 29) kg/m2 and 68% had never smoked. 4% of men had a history of cryptorchidism and 9% of varicocele. The majority of men (77%) had undergone a previous fertility exam. Men had median (IQRs) sperm concentration, total sperm count, progressive motility and morphologically normal sperm of 56.6 (24.6, 101.4) mil/mL, 123 (58.0, 229) mil/ejaculate, 24.0 (12.0, 36.0) %, and 5.0 (4.0, 8.0) %, respectively.

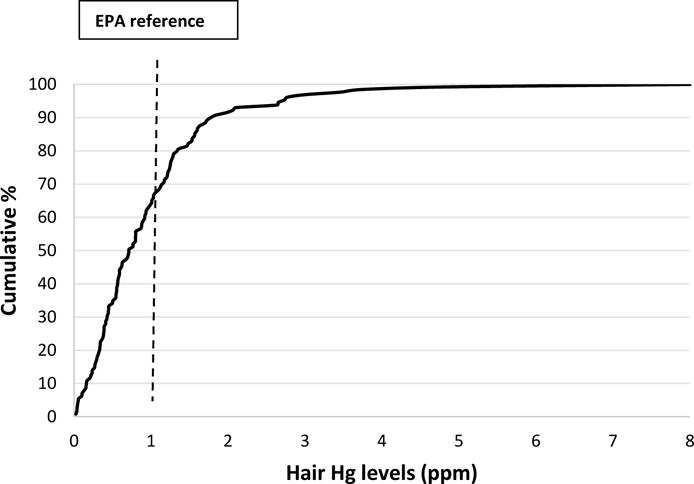

The median hair Hg levels of the men was 0.72 ppm and ranged from 0.03 to 8.01 ppm (Figure 1). Hair Hg levels were positively correlated with men’s fish intake over the past year (r = 0.59, p<0.0001). Almost 30% of the men had hair Hg levels >1ppm (US-EPA 2001). Men included in our analysis had considerably lower hair Hg levels than previously reported among fertile Japanese (3.33ppm; age range: 24–72 years) (Dickman and Leung 1998) and Finnish men (2.1 ppm; age range: 42–60 years)(Salonen et al. 1995), but higher than levels previously reported among men in Russia (.31ppm; age range: 10–59 years) (Skalnaya et al. 2016) and Wisconsin (0.30ppm; age range >50 years) (Christensen et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Distribution of hair Hg levels among 129 men in the EARTH Study.

Compared to men in the lowest quartile (range=0.03, 0.37ppm), men in the highest quartile of hair Hg (range=1.26, 8.01) were younger (median=36.8 vs. 34.8 years), heavier (median=25.9 vs. 27.7 km/m2), and had higher consumption of alcohol (median=3.4 vs. 17.2 g/day), and total fish intake (median=0.6 vs. 2.2 servings/day), (Table 1). No other demographic, dietary, reproductive or semen characteristics differed substantially across quartiles of hair Hg levels (Table 1). Men included in this analysis had slightly lower sperm concentration and total sperm count but were similar in their demographic and reproductive characteristics to men who were excluded from the analysis due to lack of dietary data or Hg levels (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, dietary, reproductive characteristics and semen parameters of 129 men in the EARTH Study by quartile of hair Hg levels (ppm).

| Quartiles of hair Hg levels (range)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (0.03, 0.37) | Q2 (0.38, 0.67) | Q3 (0.70, 1.25) | Q4 (1.26, 8.01) | p-valuea | |

| N | 30 | 31 | 36 | 32 | |

| Median (IQR) or N (%) | |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years | 36.8 (33.9, 40.0) | 38.5 (34.8, 42.5) | 35.2 (33.0, 37.8) | 34.8 (31.8, 38.4) | 0.03 |

| White (race), N (%) | 29 (97) | 27 (87) | 32 (89) | 27 (84) | 0.45 |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 25.9 (23.0, 28.4) | 28.0 (25.0, 31.8) | 25.5 (23.5, 27.8) | 27.7 (24.1, 29.5) | 0.14 |

| Ever smoked, N (%) | 9 (30) | 6 (19) | 13 (36) | 13 (41) | 0.29 |

| Diet | |||||

| Total energy intake, kcal/day | 2100 (1614, 2520) | 2105 (1668, 2604) | 2008 (1565, 2302) | 2046 (1675, 2528) | 0.88 |

| Caffeine intake, mg/day | 134 (60.2, 311) | 161 (74.6, 250) | 129 (51.1, 282) | 242 (139, 277) | 0.45 |

| Alcohol intake, g/day | 3.4 (0.78, 8.5) | 7.1 (2.1, 15.5) | 12.6 (5.6, 20.5) | 17.2 (10.6, 25.4) | .0001 |

| Total fish intake, servings/wkb | 0.6 (0, 1.3) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.0) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.4) | 2.2 (1.8, 2.7) | <.0001 |

| Reproductive history, N (%) | |||||

| Male factor infertility diagnosis | 8 (27) | 12 (39) | 7 (19) | 13 (41) | 0.24 |

| Previous infertility examc | 22 (73) | 26 (84) | 27 (75) | 23 (74) | 0.74 |

| Undescended testesc | 3 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.25 |

| Varicocele | 3 (10) | 3 (10) | 4 (11) | 2 (6) | 0.93 |

| Epididymitis | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 0.50 |

| Prostatitis | 1 (3) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.87 |

| Semen parameters | |||||

| Semen volume, mL | 2.6 (1.8, 4.0) | 2.5 (1.1, 3.4) | 2.6 (2.0, 3.9) | 3.0 (2.4, 4.0) | 0.19 |

| Sperm concentration, mil/mL | 44.0 (22.1, 68.4) | 78.1 (17.9, 109) | 47.2 (25.0, 78.9) | 63.2 (44.1, 120) | 0.14 |

| Total sperm count, mil | 90.4 (54.6, 159) | 120 (53.8, 260) | 114 (62.7, 181) | 196 (113, 338) | 0.03 |

| Progressive motility, % | 22.0 (12.0, 27.0) | 26.0 (9.0, 43.0) | 18.0 (9.5, 27.5) | 31.5 (17.0, 40.0) | 0.04 |

| Progressive motile count, mil/ejaculate | 13.4 (9.0, 43.0) | 34.0 (4.8, 88.3) | 24.9 (7.7, 55.6) | 70.2 (23.3, 130) | 0.02 |

| Normal morphologyc, % | 5.0 (3.0, 8.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 5.0 (4.0, 9.0) | 5.0 (4.0, 8.0) | 0.86 |

| Normal morphology countc, mil/ejaculate | 4.5 (2.2, 12.4) | 8.2 (2.6, 19.0) | 6.5 (2.5, 18.1) | 12.1 (5.8, 25.4) | 0.21 |

| Abstinence time, days | 2.4 (1.5, 2.9) | 2.5 (1.6, 3.2) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.0) | 2.9 (2.4, 3.2) | 0.13 |

From Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and chi-squared tests (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate) for categorical variables.

Total fish defined as the sum of dark meat fish (including canned tuna fish and other dark meat fish such as salmon and bluefish), white meat fish (including breaded fish cakes and other white meat fish such as cod, haddock, and halibut), and shellfish (including shrimp, lobster, scallops, and clams as a main dish).

These variables have missing data.

In unadjusted models, there were positive associations between hair Hg levels and some semen parameters (Table 2). Specifically, hair Hg levels were positively related with sperm concentration, total sperm count, and progressive motility (Table 2). These associations remained after adjustment for age, BMI, smoking status, abstinence time and alcohol intake. In particular, men in the highest quartile of hair mercury levels had 49%, 62% and 36% higher sperm concentration, total sperm count and progressive motility, respectively, compared to men in the lowest quartile (Table 2). Further adjustment for total fish and total calorie intakes slightly attenuated these associations and were no longer significant; compared to men in the lowest quartile of hair mercury levels, men in the highest quartile had 50%, 46% and 31% higher sperm concentration, total sperm count and progressive motility, respectively. Similarly, after adjustment for fish and total calorie intake, the same patterns of attenuated associations were observed for total progressively motile sperm count and total normal morphology sperm count (data not shown). All these negative associations were mainly driven by differences in Q4, compared to Q3, Q2 and Q1, since these lower groups had similar estimates. Semen volume and normal morphology were unrelated to hair Hg levels when the exposure was divided in quartiles. However, when Hg was used as a continuous independent variable, morphologically normal sperm was positively associated with hair Hg levels in models adjusted for age, BMI, smoking status, abstinence time and alcohol time. But this association became attenuated and but did not reach statistical significance when the model was further adjusted for fish and total calorie intake (Table 2).

Table 2.

Semen parametersa by quartiles of hair Hg levels in 129 men contributing 243 semen samples in the EARTH Study.

| Hair mercury concentrations (ppm) (range) | Semen Volume (mL) | Sperm Concentration (mil/mL) | Total Sperm Count (mil/ejaculate) | Progressive Motility (%) | Normal Morphology (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||||

| Q1 (0.03–0.37) | 2.92 (2.37, 3.48) | 37.9 (27.6, 51.9) | 96.2 (72.5, 128) | 20.5 (17.0, 24.1) | 6.0 (4.8, 7.2) |

| Q2 (0.38–0.67) | 2.41 (1.99, 2.84) | 48.0 (32.6, 70.9) | 99.3 (69.4, 142) | 26.9 (21.2, 32.6) | 6.5 (5.4, 7.6) |

| Q3 0.70–1.25) | 2.89 (2.48, 3.30) | 43.6 (33.2, 57.4) | 114 (85.8, 151) | 22.6 (17.9, 27.4) | 5.7 (4.6, 6.8) |

| Q4 (1.26–8.01) | 2.94 (2.61, 3.27) | 60.9 (48.1, 77.2)* | 167 (129, 217)* | 29.2 (24.8, 33.7)* | 6.3 (5.0, 7.5) |

| p-trend | 0.59 | 0.04 | 0.006 | 0.03 | 0.96 |

|

| |||||

| β-est (95% CI) | 0.01 (−0.19, 0.21) | 19.2 (9.2, 29.2) | 22.8 (9.3, 36.3) | 3.4 (1.9, 4.9) | 0.59 (−0.28, 1.47) |

| p, value | 0.92 | 0.0002 | 0.001 | <.0001 | 0.18 |

|

| |||||

| Adjustedc | |||||

| Q1 (0.03–0.37) | 2.86 (2.35, 3.36) | 40.1 (29.6, 54.4) | 100 (75.5, 134) | 21.2 (17.9, 24.6) | 5.8 (4.8, 6.8) |

| Q2 (0.38–0.67) | 2.48 (2.03, 2.94) | 46.7 (32.0, 68.2) | 98.8 (93.7, 140) | 26.8 (21.2, 31.2) | 6.2 (5.2, 7.3) |

| Q3 0.70–1.25) | 2.86 (2.44, 3.27) | 43.3 (33.1, 57.5) | 112 (85.0, 147) | 22.7 (18.0, 27.3) | 5.9 (4.8, 6.9) |

| Q4 (1.26–8.01) | 2.93 (2.58, 3.28) | 59.9 (46.4, 77.4)* | 162 (123, 214)* | 28.9 (24.1, 33.6)* | 6.7 (5.3, 8.1) |

| p-trend | 0.59 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.39 |

|

| |||||

| β-est (95% CI) | 0.02 (−0.18, 0.22) | 18.1 (7.6, 28.6) | 21.5 (7.7, 35.4) | 3.1 (1.5, 4.8) | 0.83 (0.07, 1.61) |

| p, value | 0.87 | 0.0009 | 0.002 | 0.0003 | 0.04 |

|

| |||||

| Adjustedd | |||||

| Q1 (0.03–0.37) | 2.97 (2.46, 3.49) | 40.1 (29.0, 55.3) | 106 (78.5, 144) | 21.7 (17.9, 25.6) | 6.3 (5.2, 7.5) |

| Q2 (0.38–0.67) | 2.51 (2.10, 2.95) | 46.7 (31.9, 68.3) | 100 (70.7, 142) | 26.9 (21.3, 32.6) | 6.3 (5.3, 7.4) |

| Q3 0.70–1.25) | 2.81 (2.39, 3.23) | 43.3 (33.0, 58.7) | 110 (83.3, 151) | 22.5 (17.3, 27.3) | 5.7 (4.7, 6.8) |

| Q4 (1.26–8.01) | 2.83 (2.44, 3.22) | 60.1 (45.7, 79.1) | 155 (116, 208) | 28.5 (23.5, 33.5) | 6.2 (4.8, 7.6) |

| p-trend | 0.92 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.70 |

|

| |||||

| β-est (95% CI) | −0.04 (−0.24, 0.15) | 18.4 (7.2, 29.5) | 18.8 (4.6, 33.1) | 2.9 (1.2, 4.6) | 0.66 (−0.28, 1.61) |

| p, value | 0.66 | 0.002 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.17 |

Data are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI).

A total of 22 semen samples (9%) had missing data for normal sperm morphology and thus total normal morphology count, resulting in a N=221 semen samples.

Models are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever and never smoked), abstinence time (continuous), and alcohol intake (gr/day).

Models are further adjusted for total calorie intake (kcal/day) and total fish intake (servings/week).

p-value <0.05 when compared that quartile with the lowest quartile of exposure.

In sensitivity analyses, we also observed positive associations when analyses were restricted to just the first two samples per man (n=129 men contributing 202 semen samples) (results not shown) and when the semen parameters were compared for men with Hg hair levels above vs below the EPA reference level (US-EPA 2001) (Table 3). Of note, total sperm count was significantly higher among men with hair Hg levels above the EPA reference levels (1 ppm) than that of men below this cutoff value even after adjustment for fish intake. When semen parameters were divided in two groups, above and below the WHO 2010 cutoffs (World Health Organization 2010), only the positive association between hair Hg levels and progressive motile sperm remained and no significant associations were observed for other semen parameters (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Semen parametersa by EPA reference for hair Hg levels (1 ppm) in 129 men contributing 243 semen samples in the EARTH Study.

| Hair mercury concentrations (ppm) | Semen Volume (mL) | Sperm Concentration (mil/mL) | Total Sperm Count (mil/ejaculate) | Progressive Motility (%) | Normal Morphology (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | |||||

| G1-lower (<1) | 2.7 (2.4, 3.0) | 42.9 (34.7, 53.0) | 99.0 (81.1, 121) | 23.3 (20.4, 26.2) | 6.1 (5.4, 6.8) |

| G2-higher (≥1) | 3.0 (2.7, 3.3) | 54.7 (44.5, 67.4) | 154 (124, 191) | 27.4 (23.2, 31.5) | 6.2 (5.1, 7.3) |

| p-value | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.004 | 0.12 | 0.84 |

|

| |||||

| Adjustedc | |||||

| G1-lower (<1) | 2.7 (2.4, 3.0) | 42.9 (35.1, 52.6) | 99.5 (82.1, 121) | 23.4 (20.5, 26.4) | 5.9 (5.3, 6.5) |

| G2-higher (≥1) | 3.0 (2.7, 3.3) | 54.8 (44.2, 68.1) | 152 (121, 190) | 27.4 (23.3, 31.6) | 6.6 (5.4, 7.7) |

| p-value | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.006 | 0.14 | 0.32 |

|

| |||||

| Adjustedd | |||||

| G1-lower (<1) | 2.7 (2.4, 3.0) | 43.1 (35.0, 53.1) | 101 (83.1, 123) | 23.7 (20.7, 26.8) | 6.2 (5.5, 6.8) |

| G2-higher (≥1) | 2.9 (2.5, 3.2) | 54.6 (43.3, 68.8) | 147 (115, 186) | 26.9 (22.3, 31.5) | 6.1 (4.9, 7.3) |

| p-value | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.98 |

Data are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI).

A total of 22 semen samples (9%) had missing data for normal sperm morphology and thus total normal morphology count, resulting in a N=221 semen samples.

Models are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever and never smoked), abstinence time (continuous), and alcohol intake (gr/day).

Models are further adjusted for total calorie intake (kcal/day) and total fish intake (servings/week).

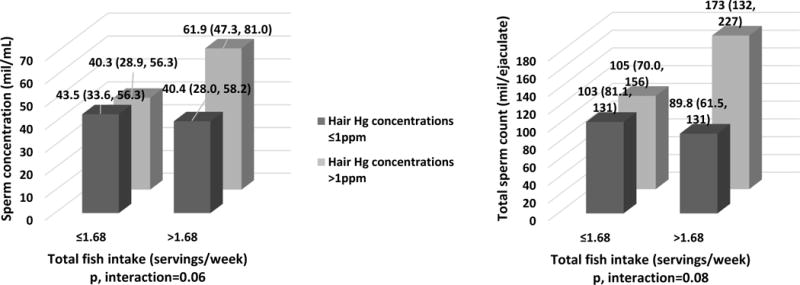

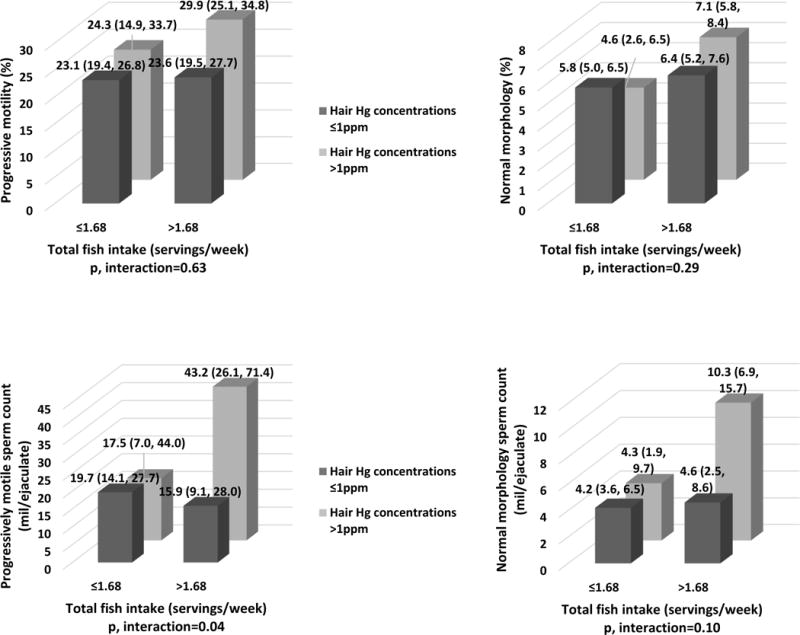

To further separate the potentially deleterious effects of Hg from the potentially beneficial effects of fish intake on semen parameters, we examined whether fish intake modified the relation between hair Hg levels and semen parameters. Among men whose fish intake was above the study population median (>1.68 servings/week), higher levels of Hg in hair (>1ppm) were positively related to progressive motile and normal morphology sperm counts (Figure 2). Hair Hg was unrelated to semen quality, however, among men whose fish intake was below the population median (Figure 2). Results were similar for sperm concentration, total sperm count and progressively motility, and no effect modification was found for morphologically normal sperm (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect modification of total fish intake on the relationship between hair Hg levels and progressive motile and normal morphology sperm counts among 129 men contributing 243 semen samples in the EARTH Study.

Data are presented as predicted marginal means (95% CI). Hair Hg levels were divided using the EPA reference level (1 ppm). Total fish intake was divided by the median in our study population (1.68 servings/week). A total of 22 semen samples (9%) had missing data for normal sperm morphology and thus total normal morphology count, resulting in a N=221 semen samples. Models are adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (continuous), smoking status (ever and never smoked), abstinence time (continuous), alcohol intake (g/day), total calorie (kcal/day) and total fish (servings/week) intakes.

Discussion

This study investigated the association between hair Hg levels and semen parameters among men attending an academic fertility center. We also explored, for the first time, whether this relationship was modified by consumption of fish, the main source of MeHg in the general population. Sperm concentration, total sperm count, progressive motility, progressive motile sperm count and normal morphology sperm count were positively associated with hair Hg levels after adjusting for potential confounders and became attenuated after further adjustment for fish intake. Furthermore, stratified analyses showed that the positive association between hair Hg levels and semen quality was only observed among men with high fish intake. These findings suggest that in this study population hair Hg may serve as a biomarker of fish intake and the interaction may be reflective of known beneficial effects of fish intake on semen quality rather than a beneficial effect of Hg per se. Moreover, our results do not support the hypothesis that Hg, within the observed range, has an adverse impact on men’s reproductive potential to the extent that clinical semen quality parameters were not adversely affected.

No previous studies have found a positive association between Hg and semen parameters. Choy and colleagues investigated whether Hg, measured in blood and seminal fluid, affected some semen parameter endpoints among subfertile men in Hong Kong (Choy et al. 2002b). Authors found different results depending of the biomarker used for assessing Hg. Specifically, abnormal sperm morphology and abnormal sperm motion were positively correlated with Hg when it was measured in seminal fluid but unrelated to blood Hg levels (Choy et al. 2002b). Meeker and coworkers explored the associations of blood concentrations of some metals and semen quality in men attending a fertility center in Michigan and also found heterogeneous results depending on how the outcomes were analyzed (Meeker et al. 2008). Specifically, blood Hg concentrations were unrelated to semen parameters when the outcomes were treated as continuous variables, but there were negative associations when these were dichotomized using WHO 1999 references for normal semen quality (World Health Organization 1999). The remainder of the epidemiologic literature on the topic has found no relation between Hg and semen quality (Chia et al. 1992; Lenters et al. 2015; Mocevic et al. 2013; Rignell-Hydbom et al. 2007; Zeng et al. 2015). However, Kim and colleagues investigated whether toxic metals, including Hg, in seminal plasma collected from 30 men who were referred to the Center for Reproductive Health of the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) for infertility treatment were associated with semen quality and vitro fertilization outcomes (Kim et al. 2014). Although seminal plasma Hg levels were not associated with semen parameters, positive associations were found between seminal plasma Hg levels and pregnancy and live birth rates. In addition, other group also explored the relation between Hg and reproductive hormones among male partners of pregnant European women living in Greenland, Poland and Ukraine and showed a positive association between blood Hg concentrations and inhibin B levels (Lenters et al. 2015; Mocevic et al. 2013), a marker of spermatogenesis. The authors concluded that this relation could be explained by a higher consumption of seafood, as a source of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, which may beneficially impact certain semen quality parameters (Attaman et al. 2012; Safarinejad 2011). Nevertheless, authors did not take into account fish consumption in the models. Our findings are in agreement with this interpretation.

In contrast to results in the present study, a detrimental effect of Hg on male reproductive outcomes has been shown in in vitro (Arabi and Heydarnejad 2007; Ernst and Lauritsen 1991; Mohamed et al. 1986; Rao 1989) and animal studies (Homma-Takeda et al. 2001; Mohamed et al. 1987; Orisakwe et al. 2001). For example, impaired spermatogenesis and decreased testosterone levels were observed in 7-week-old rats treated with Hg by subcutaneous injection at a dose of 10 ppm per day during 8 days (Homma-Takeda et al. 2001). Also, decreased sperm number and testicular weight were found in 12-week-old mice when administrated a dose of 4 ppm during the 12 weeks of life by gavage (Orisakwe et al. 2001) and adult monkeys that had blood Hg levels around 2ppm had a decreased sperm motility and sperm swimming speed, and increased abnormal sperm tail morphology (Mohamed et al. 1987). It is important to highlight the differences between these experimental models and human studies. First, the MeHg used as Hg exposure in the experiments was chemically created as MeHg chloride or MeHg hydroxide, which differ from environmental MeHg to which humans are exposed and occurs naturally. Second, exposure levels in the nonhuman studies were considerably higher (up to ten times higher compared to the EPA reference level) than usual human exposure. Third, it has been shown that the Hg kinetics (absorption, metabolism, distribution, and excretion) and toxicokinetics in humans are not comparable with those in animals (Carrier et al. 2001). Moreover, as described before, the main source of MeHg in humans is through ingestion of contaminated fish, and thus the effect of Hg exposure in humans has to be considered in terms of tradeoffs between potential risks and potential benefits, due to the well-described health benefits of fish intake on multiple health outcomes including reproductive health (Mozaffarian and Rimm 2006).

The current study has several limitations worth noting. First, due to its design including men from couples seeking fertility treatment, it may not be possible to generalize our findings to men from the general population. However, men in the EARTH Study are considered to have good semen quality (World Health Organization 2010) with comparable semen parameters to those among young healthy men from the general population in the US (Mendiola et al. 2014) and Europe (Mendiola et al. 2013). Second, our design is not totally prospective in terms of Hg and semen parameters which may limit causal inference. But it has been demonstrated that measurement of Hg in hair samples reflects Hg exposure over several months (Grandjean and Weihe 2002), which minimizes misclassification and measurement error of the exposure. Third, in relation with the previous point, as is the case of all studies based on diet questionnaires, measurement error and misclassification of fish intake are a concern. Nevertheless, intake measured with this questionnaire correlates well with biological markers of intake (Willett et al. 1985). Moreover, because intake of fish and diet were assessed prior to the semen sample collection, it is unlikely that the error was related to the outcomes. A concern specific to this particular study is that FFQs are designed to optimize the accrual of nutritional data. Hence, questions regarding fish intake were chosen to obtain information on sources of marine fatty acids, but not to distinguish fish in terms of their Hg content. For example, intakes of salmon (low Hg, high omega-3) and swordfish (high Hg, high omega-3) are combined in a single question. Hence, while simultaneous consideration of fish intake and a biomarker of Hg are a significant improvement over previous work addressing this question, residual confounding is still possible. The main strength of our study is the comprehensive adjustment of possible confounding variables, dietary (fish and total calorie intake, alcohol consumption) and non-dietary related (abstinence time, age, etc), due to the standardized assessment of a wide range of participant characteristics. Other strengths include the use of cumulative (sub-chronic) exposure biomarker and multiple semen assessments for many participants.

Conclusions

In conclusion, hair Hg levels were positively associated with some semen parameters among men of couples seeking fertility care. These associations became attenuated after adjustment for fish intake, which is the major source of Hg exposure (MeHg) in the general population, and were stronger among men whose fish intake was above the study population median. Since this is the first study taking into account the potential modification of fish intake on the relation between Hg exposure and semen quality, and because Hg has been shown to be a neurologic and reproductive toxicant (US-EPA, 2017b), further research is need to clarify the complex relationship between fish intake and Hg, and potential effects on male reproductive health, specifically, semen parameters.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

General population exposure to methylmercury occurs primarily through the consumption of contaminated fish and shellfish but it remains uncertain if exposure to mercury affects semen parameters.

-

-

Hair Hg levels were positively associated with some semen parameters among men of couples seeking fertility care.

-

-

These associations became attenuated after adjustment for fish intake and were stronger among men whose fish intake was above the study population median.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge all members of the EARTH study team, specifically Ramace Dadd, Myra G. Keller, and Patricia Morey, physicians and staff at Massachusetts General Hospital fertility center and a special thanks to all the study participants.

We would also like to thank Mr. Nicola Lupoli, Dr Innocent Jayawardene at the Trace Metals Laboratory, Harvard School of Public Health, for providing assistance and guidance with the hair mercury analysis.

Study funding: NIH grants R01ES022955, R01ES009718, and R01ES000002 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and P30DK046200 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases. M.C.A. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award T32 DK 007703–16 from NIDDK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author’s contribution to manuscript: J.E.C and R.H. were involved in study concept and design, and critical revision for important intellectual content of the manuscript. P.L.W was involved in study concept and design, and critical revision for important intellectual content of the manuscript and provided statistical expertise. L.M.A and M.C.A analyzed data, drafted the manuscript and had a primary responsibility for final content; L.M.A, M.C.A, P.L.W, M.A. R.H. and J.E.C. interpreted the data; M.A. reviewed the statistical analysis; J.B.F, C.J.A. and C.T. were involved in acquisition of the data. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest: M.C.A. is currently employed at the Nestlé Research Center, Switzerland and completed her part for this work while at the Harvard School of Public Health. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Afeiche MC, Gaskins AJ, Williams PL, Toth TL, Wright DL, Tanrikut C, et al. Processed meat intake is unfavorably and fish intake favorably associated with semen quality indicators among men attending a fertility clinic. The Journal of nutrition. 2014;144:1091–1098. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.190173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcser KH, Brix KA, Fine LJ, Kallenbach LR, Wolfe RA. Occupational mercury exposure and male reproductive health. American journal of industrial medicine. 1989;15:517–529. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700150505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabi M, Heydarnejad MS. In vitro mercury exposure on spermatozoa from normospermic individuals. Pakistan journal of biological sciences : PJBS. 2007;10:2448–2453. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.2448.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attaman JA, Toth TL, Furtado J, Campos H, Hauser R, Chavarro JE. Dietary fat and semen quality among men attending a fertility clinic. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2012;27:1466–1474. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier G, Bouchard M, Brunet RC, Caza M. A toxicokinetic model for predicting the tissue distribution and elimination of organic and inorganic mercury following exposure to methyl mercury in animals and humans. Ii. Application and validation of the model in humans. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2001;171:50–60. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia SE, Ong CN, Lee ST, Tsakok FH. Blood concentrations of lead, cadmium, mercury, zinc, and copper and human semen parameters. Archives of andrology. 1992;29:177–183. doi: 10.3109/01485019208987722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy CM, Lam CW, Cheung LT, Briton-Jones CM, Cheung LP, Haines CJ. Infertility, blood mercury concentrations and dietary seafood consumption: A case-control study. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2002a;109:1121–1125. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.02084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy CM, Yeung QS, Briton-Jones CM, Cheung CK, Lam CW, Haines CJ. Relationship between semen parameters and mercury concentrations in blood and in seminal fluid from subfertile males in hong kong. Fertility and sterility. 2002b;78:426–428. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03232-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KY, Thompson BA, Werner M, Malecki K, Imm P, Anderson HA. Levels of persistent contaminants in relation to fish consumption among older male anglers in wisconsin. International journal of hygiene and environmental health. 2016;219:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman MD, Leung KM. Mercury and organochlorine exposure from fish consumption in hong kong. Chemosphere. 1998;37:991–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(98)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst E, Lauritsen JG. Effect of organic and inorganic mercury on human sperm motility. Pharmacology & toxicology. 1991;68:440–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1991.tb01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslamian G, Amirjannati N, Rashidkhani B, Sadeghi MR, Hekmatdoost A. Intake of food groups and idiopathic asthenozoospermia: A case-control study. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2012;27:3328–3336. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean PJP, Weihe P. Biomarkers of environmental associated disease. In: Wilson SH, S W, editors. Validity of mercury exposure biomarkers. Crc press/lewis publishers; boca raton, gl: 2002. pp. 235–247. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R, Meeker JD, Duty S, Silva MJ, Calafat AM. Altered semen quality in relation to urinary concentrations of phthalate monoester and oxidative metabolites. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2006;17:682–691. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000235996.89953.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma-Takeda S, Kugenuma Y, Iwamuro T, Kumagai Y, Shimojo N. Impairment of spermatogenesis in rats by methylmercury: Involvement of stage- and cell- specific germ cell apoptosis. Toxicology. 2001;169:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck C, Bergmann M, Ernst E, Muller C, Kliesch S, Nieschlag E. Autometallographic detection of mercury in testicular tissue of an infertile man exposed to mercury vapor. Reproductive toxicology (Elmsford, NY) 1993;7:469–475. doi: 10.1016/0890-6238(93)90092-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Bloom MS, Kruger PC, Parsons PJ, Arnason JG, Byun Y, et al. Toxic metals in seminal plasma and in vitro fertilization (ivf) outcomes. Environmental research. 2014;133:334–337. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger TF, Acosta AA, Simmons KF, Swanson RJ, Matta JF, Oehninger S. Predictive value of abnormal sperm morphology in in vitro fertilization. Fertility and sterility. 1988;49:112–117. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)59660-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenters V, Portengen L, Smit LA. Phthalates, perfluoroalkyl acids, metals and organochlorines and reproductive function: A multipollutant assessment in greenlandic, polish and ukrainian men. 2015;72:385–393. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2014-102264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung TY, Choy CM, Yim SF, Lam CW, Haines CJ. Whole blood mercury concentrations in sub-fertile men in hong kong. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2001;41:75–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.2001.tb01298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor AJ, Mason HJ. Occupational mercury vapour exposure and testicular, pituitary and thyroid endocrine function. Human & experimental toxicology. 1991;10:199–203. doi: 10.1177/096032719101000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD, Rossano MG, Protas B, Diamond MP, Puscheck E, Daly D, et al. Cadmium, lead, and other metals in relation to semen quality: Human evidence for molybdenum as a male reproductive toxicant. Environmental health perspectives. 2008;116:1473–1479. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiola J, Torres-Cantero AM, Moreno-Grau JM, Ten J, Roca M, Moreno-Grau S, et al. Food intake and its relationship with semen quality: A case-control study. Fertility and sterility. 2009;91:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiola J, Moreno JM, Roca M, Vergara-Juarez N, Martinez-Garcia MJ, Garcia-Sanchez A, et al. Relationships between heavy metal concentrations in three different body fluids and male reproductive parameters: A pilot study. Environmental health : a global access science source. 2011;10:6. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiola J, Jorgensen N, Minguez-Alarcon L, Sarabia-Cos L, Lopez-Espin JJ, Vivero-Salmeron G, et al. Sperm counts may have declined in young university students in southern spain. Andrology. 2013;1:408–413. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2012.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiola J, Jorgensen N, Andersson AM, Stahlhut RW, Liu F, Swan SH. Reproductive parameters in young men living in rochester, new york. Fertility and sterility. 2014;101:1064–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocevic E, Specht IO, Marott JL, Giwercman A, Jönsson BAG, Toft G, et al. Environmental mercury exposure, semen quality and reproductive hormones in greenlandic inuit and european men: A cross-sectional study. Asian journal of andrology. 2013;15:97–104. doi: 10.1038/aja.2012.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MK, Lee WI, Mottet NK, Burbacher TM. Laser light-scattering study of the toxic effects of methylmercury on sperm motility. Journal of andrology. 1986;7:11–15. doi: 10.1002/j.1939-4640.1986.tb00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MK, Burbacher TM, Mottet NK. Effects of methyl mercury on testicular functions in macaca fascicularis monkeys. Pharmacology & toxicology. 1987;60:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health: Evaluating the risks and the benefits. Jama. 2006;296:1885–1899. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.15.1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orisakwe OE, Afonne OJ, Nwobodo E, Asomugha L, Dioka CE. Low-dose mercury induces testicular damage protected by zinc in mice. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2001;95:92–96. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00374-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizent A, Tariba B, Zivkovic T. Reproductive toxicity of metals in men. Arhiv za higijenu rada i toksikologiju. 2012;63(Suppl 1):35–46. doi: 10.2478/10004-1254-63-2012-2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachootin P, Olsen J. The risk of infertility and delayed conception associated with exposures in the danish workplace. Journal of occupational medicine : official publication of the Industrial Medical Association. 1983;25:394–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MV. Toxic effects of methylmercury on spermatozoa in vitro. Experientia. 1989;45:985–987. doi: 10.1007/BF01953057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rignell-Hydbom A, Axmon A, Lundh T, Jonsson BA, Tiido T, Spano M. Dietary exposure to methyl mercury and pcb and the associations with semen parameters among swedish fishermen. Environmental health : a global access science source. 2007;6:14. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-6-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. American journal of epidemiology. 1992;135:1114–1126. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. discussion 1127–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney KL, Domar AD. The impact of lifestyle behaviors on infertility treatment outcome. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;26:181–185. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safarinejad MR. Effect of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation on semen profile and enzymatic anti-oxidant capacity of seminal plasma in infertile men with idiopathic oligoasthenoteratospermia: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised study. Andrologia. 2011;43:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen JT, Seppanen K, Nyyssonen K, Korpela H, Kauhanen J, Kantola M, et al. Intake of mercury from fish, lipid peroxidation, and the risk of myocardial infarction and coronary, cardiovascular, and any death in eastern finnish men. Circulation. 1995;91:645–655. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvini S, Hunter DJ, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, et al. Food-based validation of a dietary questionnaire: The effects of week-to-week variation in food consumption. International journal of epidemiology. 1989;18:858–867. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle SR, Speed FM, Milliken GA. Population marginal means in the linear model: An alternative to least square means. Am Stat. 1980;34:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Biedenharn KR, Fedor JM, Agarwal A. Lifestyle factors and reproductive health: Taking control of your fertility. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2013;11:66. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalnaya MG, Tinkov AA, Demidov VA, Serebryansky EP, Nikonorov AA, Skalny AV. Age-related differences in hair trace elements: A cross-sectional study in orenburg, russia. Annals of human biology. 2016;43:438–444. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2015.1071424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US-EPA. US Environmental protection agency. Integrated risk information system methylmercury (mehg) (casrn 22967-92-6) 2001 Available at: Https://cfpub.Epa.Gov/ncea/iris/iris_documents/documents/subst/0073.Htm [accessed april, 2017]

- US-EPA. U.S. Environmental protection agency. Food and drug administration (fda) joint federal advisory for mercury in fish. What you need to know about mercury in fish and shellfish. 2017a Available at: Http://water.Epa.Gov/scitech/swguidance/fishshellfish/outreach/advice_index.Cfm [accessed march 2017]

- US-EPA. U.S. Environmental protection agency. Mercury in your environment. 2017b Available at: Https://www.Epa.Gov/mercury [accessed march 2017]

- Vujkovic M, de Vries JH, Dohle GR, Bonsel GJ, Lindemans J, Macklon NS, et al. Associations between dietary patterns and semen quality in men undergoing ivf/icsi treatment. Human reproduction (Oxford, England) 2009;24:1304–1312. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng H-Y, Hsueh Y-H, Messam LLM, Hertz-Picciotto I. Methods of covariate selection: Directed acyclic graphs and the change-in-estimate procedure. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169:1182–1190. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett W, Sampson L, Stampfer M, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. American journal of epidemiology. 1985;122:51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Who laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. 4th. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Who laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. 5th. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Feng W, Zhou B, Wang YX, He XS, Yang P, et al. Urinary metal concentrations in relation to semen quality: A cross-sectional study in china. Environmental science & technology. 2015;49:5052–5059. doi: 10.1021/es5053478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.