Abstract

Background

Studies on multiple dimensions of the symptom experience of patients with gastrointestinal cancers are extremely limited. Purpose was to evaluate for changes over time in the occurrence, severity, and distress of seven common symptoms in these patients.

Methods

Patients completed Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale, six times over two cycles of CTX. Changes over time in occurrence, severity, and distress of pain, lack of energy, nausea, feeling drowsy, difficulty sleeping, and change in the way food tastes were evaluated using multilevel regression analyses. In the conditional models, effects of treatment group (i.e., with or without targeted therapy (TT)), age, number of metastatic sites, time from cancer diagnosis, number of prior cancer treatments, cancer diagnosis, and CTX regimen on enrollment levels, as well as the trajectories of symptom occurrence, severity, and distress were evaluated.

Results

While the occurrence rates for pain, lack of energy, feeling drowsy, difficulty sleeping, and change in the way food tastes declined over the two cycles of CTX, nausea and numbness/tingling in hands/feet had more complex patterns of occurrence. Severity and distress ratings for the seven symptoms varied across the two cycles of CTX.

Conclusions

Demographic and clinical characteristics associated with differences in enrollment levels as well as changes with changes over time in occurrence, severity, and distress of these seven common symptoms were highly variable. These findings can be used to identify patients who are at higher risk for more severe and distressing symptoms during CTX and to enable the initiation of pre-emptive symptom management interventions.

Keywords: gastrointestinal cancer, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, severity, distress, pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, taste changes, feeling drowsy

INTRODUCTION

Patients with gastrointestinal (GI) cancers who receive chemotherapy (CTX), with or without targeted therapy (TT), experience multiple co-occurring symptoms.1 In fact, in a recent cross-sectional study,2 our research team evaluated the occurrence, severity, and distress of acute symptoms in the week following CTX administration using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS). While significant differences were found in the symptom experience of GI cancer patients who received CTX alone compared to CTX with TT, both groups reported an average of 12.5 symptoms. After controlling for a number of clinically meaningful covariates, patients who received CTX with TT reported lower occurrence rates for lack of energy, cough, feeling drowsy, and difficulty sleeping. In addition, these patients reported lower severity scores for dry mouth and change in the way food tastes. However, they reported significantly higher severity scores for worrying and “I don’t look like myself”. No differences in symptom distress scores were found between the two treatment groups.

As noted by an expert panel convened by the National Institute of Nursing Research,33 additional information is needed on changes over time in multiple dimensions (i.e., occurrence, severity, distress) of patients’ symptom experiences. In addition, consideration should be given to an evaluation of how pertinent demographic (e.g., age) and clinical (e.g., diagnosis, type of treatment) influence initial levels as well as the trajectories of various symptoms.

However, longitudinal studies of the symptom experience of patients with GI cancers are extremely limited. To our knowledge, only one study evaluated for changes over time in the symptom experience of patients with GI cancers. In this study,4 changes in the occurrence of depressive symptoms and associated predictors were assessed in patients with metastatic GI (n=376) and lung (n=166) cancer who were receiving CTX. While the occurrence and severity of depressive symptoms increased in the final months of life, results were not reported separately for the two cancer diagnoses.

Given the paucity of longitudinal studies of the symptom experience of patients with GI cancers, the purpose of this study was to evaluate for changes over time in the occurrence, severity, and distress of seven common symptoms (i.e., pain, lack of energy, nausea, feeling drowsy, numbness/tingling in hands/feet, difficulty sleeping, change in the way food tastes) in a sample of patients with GI cancers who were assessed over two cycles of CTX. In addition, the effects of a number of demographic and clinical characteristics that are known to influence cancer patients’ symptom experience (i.e., treatment group (i.e., CTX with and without TT,2,5 age,6,7 number of metastatic sites,8,9 time from cancer diagnosis,8,9 total number of prior cancer treatments,8,9 cancer diagnosis,10 CTX regimen11) on enrollment scores, as well as on changes over time in the various dimensions of the symptom experience were evaluated.

METHODS

Patients and Settings

This study is part of a larger descriptive, longitudinal study of the symptom experience of oncology outpatients who received CTX.12,13 Patients were included if they were ≥18 years of age; had a diagnosis of breast, GI, lung, or gynecological cancer; had received CTX within the preceding four weeks; were scheduled to receive at least two additional cycles of CTX; were able to read, write, and understand English; and provided written informed consent. Patients were recruited from two Comprehensive Cancer Centers, one Veterans Affairs hospital, and four community based oncology programs. The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California at San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites.

Instruments

A demographic questionnaire obtained information on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, living alone (yes/no), education, employment status, and income. Functional status was assessed using the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale, which is widely used in patients with cancer and has well established validity and reliability.14 Patients rated their functional status using the KPS scale that ranged from 30 (I feel severely disabled and need to be hospitalized) to 100 (I feel normal; I have no complaints or symptoms).15,16

Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) consists of 13 common medical conditions simplified into language that can be understood without prior medical knowledge.17 Patients indicated if they had the condition; if they received treatment for it (proxy for disease severity); and if it limited their activity (indication of functional limitations). For each condition, patients can receive a maximum of 3 points. The total SCQ score ranges from 0 to 39. The SCQ has well established validity and reliability.17

A modified version of the MSAS was used to evaluate the occurrence, severity, and distress of 38 symptoms commonly associated with cancer and its treatment. In addition to the original 32 MSAS symptoms, the following six symptoms, found on other symptom assessment instruments, were assessed: hot flashes, chest tightness, difficulty breathing, abdominal cramps, increased appetite, and weight gain. These symptoms were added to the MSAS because they are common symptoms in oncology patients.

The MSAS is a self-report questionnaire designed to measure the multidimensional experience of symptoms. Patients were asked to indicate whether they experienced each symptom within the past week (i.e., symptom occurrence). If they experienced the symptom, they were asked to rate its severity and distress. Severity was rated using a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 = slight, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, 4 = very severe). Distress was rated using a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, 2 = somewhat, 3 = quite a bit, 4 = very much). The validity and reliability of the MSAS are well established.18–20

Study Procedures

A total of 2,234 patients were approached and 1,343 consented to participate (60.1% response rate) in the larger study. The major reason for refusal was being overwhelmed with their cancer treatment. For this study, only patients with a diagnosis of a GI cancer were include (n=404). A research staff member in the infusion unit approached eligible patients and discussed participation in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Patients were recruited during the second or third cycle of CTX. Based on the length of the CTX cycle (i.e., 14 days, 21 days, 28 days) GI cancer patients completed self-report questionnaires in their homes, a total of six times over two cycles of CTX, namely: before CTX administration (i.e., recovery from previous CTX cycle, Times 1 [T1] and 4 [T4]), approximately one week after CTX administration (i.e., acute symptoms, Times 2 [T2] and 5 [T5]), and approximately two weeks after CTX administration [i.e., potential nadir, Times 3 [T3] and 6 [T6]).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were done using SPSS Version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY) and Stata/SE 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics as means and standard deviations for quantitative variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables were calculated for all of the study variables.

While the modified MSAS evaluated 38 symptoms, changes over time in occurrence, severity, and distress of the seven most common symptoms (i.e., symptoms that occurred in ≥50% of the patients at the initiation of their next CTX cycle), namely, pain, lack of energy, nausea, feeling drowsy, numbness/tingling in hands/feet, difficulty sleeping, change in the way food tastes, were evaluated in these longitudinal analyses. Based on a review of the literature of characteristics that are known to influence the symptom experience of patients with cancer, treatment group (i.e., CTX with and without TT2,5) age,6,7 number of metastatic sites,8,9 time from cancer diagnosis,8,9 total number of prior cancer treatments,8,9 cancer diagnosis,10 and CTX regimen11 were included as covariates in our longitudinal analyses.

For each of the seven symptoms, multilevel regression analysis was used to estimate changes over time in symptom occurrence, severity, and distress (i.e., a total of six assessments over two cycles of CTX). Symptom occurrence was coded as a binary variable (yes = 1 and no = 0) and changes were evaluated using multilevel logistic regression. Symptom severity was coded as an ordinal variable, with increasing severity ratings from 1 to 4. Symptom distress was coded as an ordinal variable (i.e., with 0 = not at all, 1 = a little bit, and increasing distress ratings from 2 to 4). Changes over time in symptom severity and distress were examined with multilevel ordinal logistic regression employing the logistic cumulative distribution function.21–23

First, unconditional models were examined to estimate the linear change in each of the symptoms. Given the possibility that the growth trajectory might not be only linear, quadratic effects were examined. In addition, because the length of treatment and two treatment cycles invited the examination of shifts in the growth trajectories (also called “discontinuities),22 piecewise models were examined. The piecewise model had four segments: enrollment (T1) to the T2, T2 to T3, T4 to T5, and T5 to T6. After identifying the best fitting growth trajectory for each symptom (i.e., linear, linear plus quadratic, or piecewise), conditional models were fit to examine the association between each of the covariates (i.e., treatment group, age, number of metastatic sites, time from cancer diagnosis, number of prior cancer treatments, cancer diagnosis, CTX regimen) and each of the symptoms at enrollment and on changes in each of the symptoms over time (i.e., cross-level interaction).22 A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A total of 404 patients with GI cancers consented to participate and 401 (99%) completed the MSAS at T1. As shown in Table 1, the majority of the patients were male (55.2%), married/partnered (67.5%), and had a diagnosis of colon, rectal, or anal cancer (63.7%). The patients had a mean age of 58.0 (±11.8) years, reported an average of 5.4 (±2.9) comorbidities, and had a KPS score of 80.8 (±12.5).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Sample (n=404)

| Characteristics | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age (years) | 58.0 (11.8) |

|

| |

| Education (years) | 16.0 (3.1) |

|

| |

| Karnofsky Performance Status score | 80.8 (12.5) |

|

| |

| Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire score | 5.4 (2.9) |

|

| |

| Time since cancer diagnosis (years) | 1.4 (2.9) |

|

| |

| Time since diagnosis (median) | 0.42 |

|

| |

| Number of prior cancer treatments | 1.4 (1.3) |

|

| |

| Number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvement | 1.5 (1.1) |

|

| |

| % (n) | |

|

| |

| Female | 44.8 (181) |

|

| |

| Married/Partnered (% yes) | 67.5 (270) |

|

| |

| Lives alone (% yes) | 19.0 (76) |

|

| |

| Currently employed (% yes) | 34.3 (136) |

|

| |

| Type of prior cancer treatment | |

| No prior treatment | 29.0 (113) |

| Only surgery, CTX, or RT | 38.3 (149) |

| Surgery & CTX, or surgery & RT, or CTX & RT | 21.9 (85) |

| Surgery & CTX & RT | 10.8 (42) |

|

| |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| Colon/rectum/anal | 63.7 (252) |

| Pancreatic/liver/gall bladder/esophageal/gastric/small intestine/and other | 36.3 (144) |

|

| |

| Genetic testing (% yes) | |

| BRAF detected | 2.3 (9) |

| KRAS detected | 12.7 (50) |

|

| |

| Metastatic sites | |

| No metastasis | 19.3 (77) |

| Only lymph node metastasis | 19.6 (78) |

| Only metastatic disease in other sites | 28.6 (114) |

| Metastatic disease in lymph nodes/and other sites | 32.4 (129) |

|

| |

| Chemotherapy regimen | |

| FOLFIRI | 13.9 (56) |

| FOLFOX | 43.6 (176) |

| FOLFIRINOX | 10.9 (44) |

| Other | 31.7 (128) |

|

| |

| Targeted therapy | |

| Yes | 23.4 (93) |

| No | 76.6 (304) |

Abbreviations: BRAF = B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase, CTX = chemotherapy, FOLFIRI = leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan, FOLFIRINOX = leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan/oxaliplatin, FOLFOX = leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin, KRAS = Kristen rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog, RT = radiation therapy, SD = standard deviation

Changes in Symptom Occurrence, Severity, and Distress Ratings

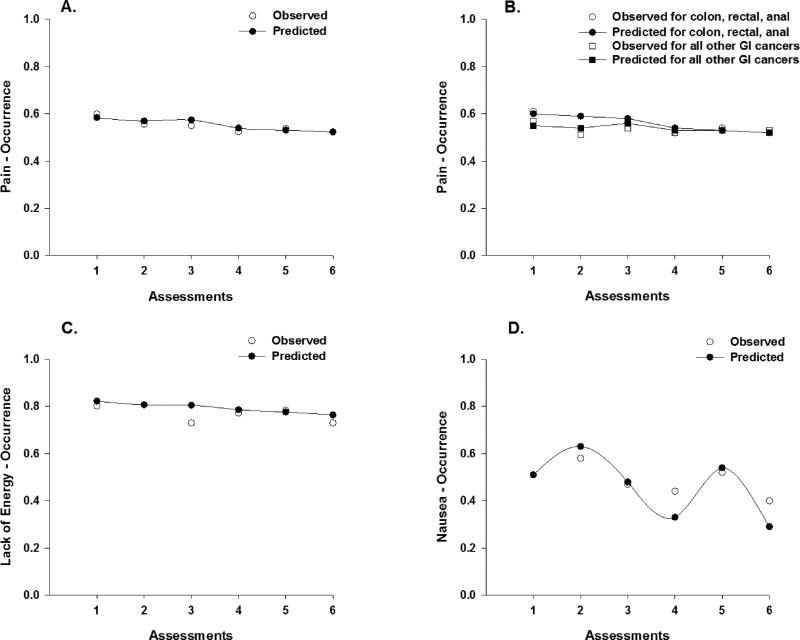

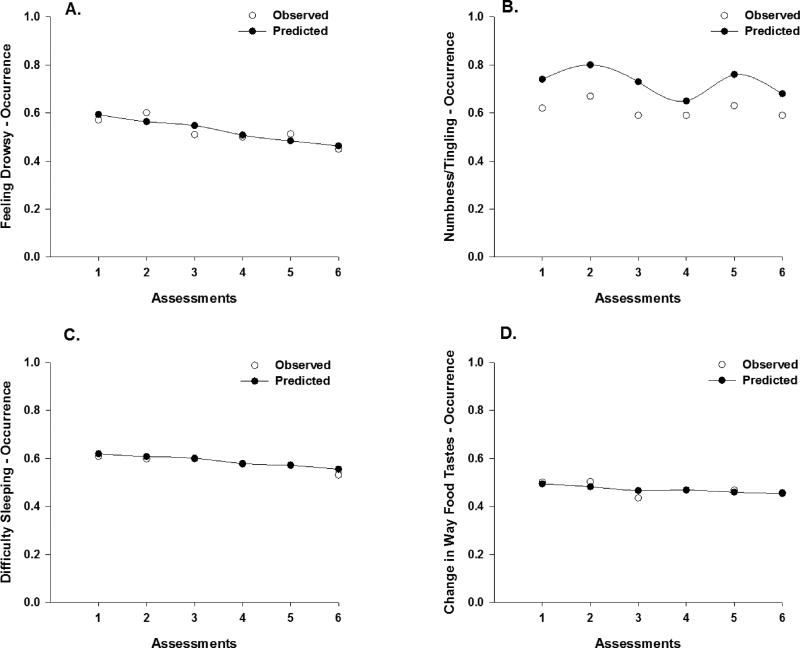

Tables 2, 3, and 4 present the results of the multilevel regression analyses for occurrence, severity, and distress ratings, respectively for the seven symptoms that were evaluated in this study. Most of the results are presented in tabular format with accompanying figures. The figures for the unconditional model of the occurrence of the various symptoms illustrate the change in the observed and predicted probability of the occurrence of that symptom over time (Figures 1 and 2). For the conditional models, each of the figures displays the probability that a patient would report the occurrence of each symptom conditioned on the values of the predictor. This predicted probability can be compared with the observed responses at each time point to determine how well the estimated trajectories match the observed responses.

Table 2.

Results of the Multilevel Regression Analyses of Occurrence Ratings for the Seven Symptoms that Occurred in ≥50% of the Patients

| Pain – Occurrence (n=401) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Model | Conditional Model | |||||||

| OR | SE | CI | p-value | OR | SE | CI | p-value | |

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.84–0.99 | 0.022 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.84–0.99 | 0.021 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.92–0.97 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.83–0.98 | 0.020 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.13 | 0.07 | 1.005–1.27 | 0.041 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.83–0.98 | 0.019 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.80 | 0.24 | 1.38–2.34 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Linear | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.89–1.15 | 0.884 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is colon = no) | 1.94 | 0.81 | 0.86–4.38 | 0.108 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | 0.84 | 0.07 | 0.71–0.998 | 0.047 | ||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Lack of Energy – Occurrence (n=401) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.84–0.99 | 0.022 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.84–0.99 | 0.022 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.95–0.999 | 0.038 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.84–0.98 | 0.016 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.17 | 0.08 | 1.03–1.33 | 0.016 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Linear (FOLFIRI as reference) | 0.83 | 0.09 | 0.66–1.04 | 0.099 | ||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction: omnibus test | X2 = 9.02; p = 0.029 | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction: pairwise comparisons* | ||||||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFOX (1 v 2) | 1.00 | 0.13 | 0.71–1.41 | >0.999 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFIRINOX (1 v 3) | 1.48 | 0.25 | 0.95–2.30 | 0.125 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs Other (1 v 4) | 1.16 | 0.16 | 0.81–1.66 | >0.999 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs FOLFIRINOX (2 v 3) | 1.47 | 0.20 | 1.02–2.12 | 0.039 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs Other (2 v 4) | 1.16 | 0.11 | 0.90–1.49 | 0.760 | ||||

| FOLFIRINOX vs Other (3 v 4) | 0.79 | 0.11 | 0.54–1.15 | 0.581 | ||||

| Nausea – Occurrence (n=401) | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.68 | 0.34 | 1.13–2.50 | 0.011 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.18–0.55 | <0.001 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 4.47 | 1.34 | 2.48–8.06 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.07–0.32 | <0.001 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.67 | 0.34 | 1.12–2.49 | 0.012 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.18–0.56 | <0.001 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 4.45 | 1.34 | 2.47–8.01 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.15 | 0.06 | 0.07–0.32 | <0.001 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.91–0.96 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Feeling Drowsy – Occurrence (n=401) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.85 | 0.03 | 0.79–0.91 | <0.001 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.84 | 0.03 | 0.79–0.91 | <0.001 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is targeted therapy = no) | 0.47 | 0.15 | 0.25–0.88 | 0.018 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Numbness/Tingling in Hands/Feet – Occurrence (n=401) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.32 | 0.28 | 0.87–2.01 | 0.192 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.29–0.92 | 0.025 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.45 | 0.75 | 1.34–4.48 | 0.004 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.18–0.93 | 0.034 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.31 | 0.28 | 0.86–2.01 | 0.201 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.29–0.93 | 0.027 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.47 | 0.77 | 1.34–4.54 | 0.004 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.18–0.938 | 0.035 | ||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction: omnibus test | X2 = 16.04; p = 0.003 | |||||||

| P1 by Age | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.97–1.04 | 0.989 | ||||

| P2 by Age | 1.03 | 0.03 | 0.98–1.08 | 0.210 | ||||

| P3 by Age | 0.94 | 0.03 | 0.89–0.99 | 0.027 | ||||

| P4 by Age | 1.05 | 0.04 | 0.98–1.13 | 0.203 | ||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.32 | 0.28 | 0.87–2.01 | 0.189 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.52 | 0.15 | 0.29–0.92 | 0.025 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.45 | 0.76 | 1.34–4.49 | 0.004 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.18–0.93 | 0.033 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.72 | 0.10 | 0.54–0.96 | 0.026 | ||||

| Cross level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.34 | 0.29 | 0.87–2.04 | 0.180 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.29–0.91 | 0.023 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.44 | 0.76 | 1.33–4.48 | 0.004 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.18–0.94 | 0.036 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is colon = no) | 2.16 | 0.73 | 1.11–4.20 | 0.023 | ||||

| Cross level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.34 | 0.29 | 0.88–2.03 | 0.177 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.51 | 0.15 | 0.29–0.91 | 0.022 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.47 | 0.76 | 1.35–4.51 | 0.003 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.41 | 0.17 | 0.18–0.93 | 0.033 | ||||

| Enrollment: omnibus test | X2 = 39.86; p <0.001 | |||||||

| Enrollment: pairwise comparisons* | ||||||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFOX (1 v 2) | 9.70 | 4.76 | 2.66–35.38 | <0.001 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFIRINOX (1 v 3) | 3.16 | 2.00 | 0.60–16.71 | 0.409 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs Other (1 v 4) | 1.11 | 0.55 | 0.30–4.07 | >0.999 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs FOLFIRINOX (2 v 3) | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.08–1.33 | 0.216 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs Other (2 v 4) | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.04–0.31 | <0.001 | ||||

| FOLFIRINOX vs Other (3 v 4) | 0.35 | 0.19 | 0.08–1.49 | 0.336 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Difficulty Sleeping – Occurrence (n=401) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.83–0.96 | 0.004 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.82–0.96 | 0.003 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is targeted therapy = no) | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.19–0.86 | 0.018 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.83–0.96 | 0.004 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.92–0.97 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.82–0.96 | 0.002 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.56 | 0.20 | 1.22–2.00 | <0.001 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Change In the Way Food Tastes – Occurrence (n=401) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.84–0.99 | 0.024 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Linear (FOLFIRI is reference) | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.84–0.99 | 0.023 | ||||

| Enrollment: omnibus test | X2 = 9.41; p=0.024 | |||||||

| Enrollment: pairwise comparisons* | ||||||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFOX (1 v 2) | 3.72 | 1.87 | 0.99–14.01 | 0.053 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFIRINOX (1 v 3) | 1.65 | 1.10 | 0.29–9.49 | >0.999 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs Other (1 v 4) | 1.54 | 0.80 | 0.39–6.10 | >0.999 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs FOLFIRINOX (2 v 3) | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.10–1.95 | 0.888 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs Other (2 v 4) | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.15–1.14 | 0.130 | ||||

| FOLFIRINOX vs Other (3 v 4) | 0.93 | 0.54 | 0.20–4.31 | >0.999 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

CI = confidence interval; FOLFIRI = leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan; FOLFIRINOX = leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan/oxaliplatin; NS = not significant; OR = odds ratio; P1 = enrollment to time 2; P2 = time 2 to time 3; P3 = time 4 to time 5; P4 = time 5 to time 6; SE = standard error

Estimates of odds ratios from three models, each with a different reference category in order to obtain Bonferroni post hoc pairwise comparisons: alpha’ for six comparisons controlled at .0083 (.05/6).

For chemotherapy regiment: 1 = FOLFIRI; 2 = FOLFOX; 3 = FOLFIRINOX; 4 = Other

Table 3.

Results of the Multilevel Regression Analyses of Severity Ratings for the Seven Symptoms that Occurred in ≥50% of the Patients

| Pain – Severity (n=293) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Model | Conditional Model | |||||||

| OR | SE | CI | p-value | OR | SE | CI | p-value | |

| Linear | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.88–1.03 | NS | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.87–1.03 | 0.232 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.32 | 0.15 | 1.06–1.65 | 0.015 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.81 | 0.06 | 0.70–0.94 | 0.006 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is Colon=no) | 0.91 | 0.34 | 0.43–1.91 | 0.793 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | 1.27 | 0.12 | 1.06–1.52 | 0.009 | ||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Lack of Energy – Severity (n=370) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.56 | 0.28 | 1.10–2.23 | 0.013 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.41 | 0.10 | 0.25–0.67 | <0.001 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 3.56 | 0.96 | 2.09–6.04 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.11–0.47 | <0.001 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.58 | 0.32 | 1.06–2.34 | 0.024 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.48 | 0.13 | 0.28–0.83 | 0.008 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.37 | 0.73 | 1.30–4.33 | 0.005 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.29 | 0.12 | 0.13–0.64 | 0.002 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.998 | 0.06 | 0.88–1.13 | 0.972 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction: omnibus test | X2 = 10.54; p = 0.032 | |||||||

| P1 by Time from cancer diagnosis | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.88–1.11 | 0.854 | ||||

| P2 by Time from cancer diagnosis | 0.92 | 0.07 | 0.79–1.08 | 0.299 | ||||

| P3 by Time from cancer diagnosis | 1.28 | 0.12 | 1.06–1.54 | 0.010 | ||||

| P4 by Time from cancer diagnosis | 0.87 | 0.10 | 0.69–1.09 | 0.212 | ||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.55 | 0.28 | 1.09–2.21 | 0.015 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.42 | 0.10 | 0.26–0.68 | <0.001 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 3.47 | 0.94 | 2.04–5.90 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.11–0.47 | <0.001 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.33 | 0.15 | 1.07–1.65 | 0.011 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Nausea – Severity (n=282) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.09 | 0.26 | 0.69–1.72 | 0.706 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.80 | 0.25 | 0.43–1.49 | 0.485 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.68 | 0.93 | 1.36–5.29 | 0.004 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.06–0.34 | <0.001 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.10 | 0.26 | 0.69–1.73 | 0.693 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.80 | 0.25 | 0.43–1.48 | 0.476 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.67 | 0.93 | 1.36–5.27 | 0.005 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.06–0.35 | <0.001 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.96 | 0.01 | 0.93–0.99 | 0.008 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Feeling Drowsy – Severity (n=316) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.89–1.05 | NS | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.89–1.06 | 0.481 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.96–0.999 | 0.038 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Numbness/Tingling in Hands/Feet – Severity (n=314) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.35 | 0.28 | 0.90–2.04 | 0.152 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.31–0.96 | 0.036 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.04 | 0.63 | 1.11–3.72 | 0.021 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.23–1.09 | 0.084 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.33 | 0.28 | 0.88–2.01 | 0.170 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.56 | 0.16 | 0.32–0.97 | 0.040 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.06 | 0.63 | 1.13–3.76 | 0.019 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.22–1.09 | 0.080 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.57 | 0.22 | 1.20–2.07 | 0.001 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.33 | 0.28 | 0.88–2.01 | 0.174 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.55 | 0.16 | 0.31–0.97 | 0.037 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.12 | 0.65 | 1.16–3.88 | 0.015 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.22–1.07 | 0.074 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is Colon = no) | 2.66 | 1.03 | 1.25–5.68 | 0.011 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Difficulty Sleeping – Severity (n=311) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.99 | 0.04 | 0.91–1.07 | NS | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Linear | 1.04 | 0.05 | 0.95–1.14 | 0.425 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is targeted therapy = no) | 2.79 | 1.28 | 1.13–6.88 | 0.026 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | 0.75 | 0.08 | 0.61–0.92 | 0.007 | ||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.91–1.07 | 0.683 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.44 | 0.17 | 1.14–1.82 | 0.002 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.99 | 0.04 | 0.91–1.07 | 0.750 | ||||

| Enrollment: omnibus test | X2 = 8.59; p = 0.035 | |||||||

| Enrollment: pairwise comparisons* | ||||||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFOX (1 v 2) | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.08–1.25 | 0.168 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs FOLFIRINOX (1 v 3) | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.03–0.90 | 0.031 | ||||

| FOLFIRI vs Other (1 v 4) | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.07–1.16 | 0.113 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs FOLFIRINOX (2 v 3) | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.12–2.01 | >0.999 | ||||

| FOLFOX vs Other (2 v 4) | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0.33–2.35 | >0.999 | ||||

| FOLFIRINOX vs Other (3 v 4) | 1.79 | 0.98 | 0.42–7.61 | >0.999 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Change In the Way Food Tastes – Severity (n=271) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.06 | 0.23 | 0.69–1.63 | 0.782 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.60 | 0.18 | 0.33–1.09 | 0.093 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 3.78 | 1.25 | 1.98–7.24 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.28 | 0.12 | 0.12–0.67 | 0.004 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.09 | 0.24 | 0.71–1.68 | 0.700 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.58 | 0.18 | 0.32–1.05 | 0.070 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 4.10 | 1.37 | 2.13–7.88 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.11–0.63 | 0.003 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.90 | 0.05 | 0.81–0.999 | 0.048 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

CI = confidence interval; FOLFIRI = leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan; FOLFIRINOX = leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan/oxaliplatin; NS = not significant; OR = odds ratio; P1 = enrollment to time 2; P2 = time 2 to time 3; P3 = time 4 to time 5; P4 = time 5 to time 6; SE = standard error

Estimates of odds ratios from three models, each with a different reference category in order to obtain Bonferroni post hoc pairwise comparisons: alpha’ for six comparisons controlled at .0083 (.05/6).

For chemotherapy regiment: 1 = FOLFIRI; 2 = FOLFOX; 3 = FOLFIRINOX; 4 = Other

Table 4.

Results of the Multilevel Regression Analyses of Distress Ratings for the Seven Symptoms that Occurred in ≥50% of the Patients

| Pain – Distress (n=292) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Model | Conditional Model | |||||||

| OR | SE | CI | p-value | OR | SE | CI | p-value | |

| Linear | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.84–0.97 | 0.007 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.86 | 0.04 | 0.79–0.94 | 0.001 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.93 | 0.05 | 0.83–1.04 | 0.217 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | 1.03 | 0.01 | 1.005–1.05 | 0.017 | ||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.90 | 0.03 | 0.84–0.97 | 0.007 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.29 | 0.15 | 1.02–1.62 | 0.030 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Lack of Energy – Distress (n=366) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.47 | 0.24 | 1.07–2.03 | 0.017 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.41 | 0.09 | 0.27–0.64 | <0.001 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.85 | 0.68 | 1.79–4.53 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.43 | 0.13 | 0.23–0.79 | 0.007 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.47 | 0.24 | 1.06–2.01 | 0.019 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.42 | 0.09 | 0.27–0.64 | <0.001 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.84 | 0.68 | 1.78–4.54 | <0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.23–0.79 | 0.007 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.27 | 0.13 | 1.03–1.55 | 0.025 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Nausea – Distress (n=281) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.90 | 0.04 | 0.83–0.98 | 0.015 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Feeling Drowsy – Distress (n=313) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.39 | 0.28 | 0.94–2.06 | 0.095 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.53 | 0.14 | 0.31–0.91 | 0.020 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.61 | 0.81 | 1.42–4.78 | 0.002 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.30 | 0.13 | 0.13–0.69 | 0.004 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Numbness/Tingling in Hands/Feet – Distress (n=315) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.01 | 0.19 | 0.70–1.46 | 0.941 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.48–1.29 | 0.342 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.05 | 0.56 | 1.20–3.52 | 0.009 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.22–0.91 | 0.027 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.01 | 0.19 | 0.70–1.46 | 0.950 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.48–1.30 | 0.358 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.01 | 0.55 | 1.17–3.45 | 0.011 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.22–0.92 | 0.029 | ||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction: omnibus test | X2 = 16.62; p = 0.002 | |||||||

| Cross-level P1 assessments | 1.03 | 0.02 | 1.0002–1.07 | 0.048 | ||||

| Cross-level P2 assessments | 0.95 | 0.02 | 0.91–0.998 | 0.039 | ||||

| Cross-level P3 assessments | 1.08 | 0.03 | 1.03–1.13 | 0.003 | ||||

| Cross-level P4 assessments | 0.92 | 0.03 | 0.86–0.98 | 0.016 | ||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.01 | 0.19 | 0.70–1.46 | 0.937 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.79 | 0.20 | 0.48–1.29 | 0.340 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.05 | 0.56 | 1.20–3.52 | 0.009 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.22–0.91 | 0.027 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.36 | 0.18 | 1.05–1.77 | 0.022 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.02 | 0.19 | 0.70–1.47 | 0.934 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.78 | 0.20 | 0.47–1.28 | 0.323 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.09 | 0.58 | 1.22–3.59 | 0.007 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.22–0.92 | 0.029 | ||||

| Enrollment (Reference is Colon=no) | 2.46 | 0.92 | 1.18–5.12 | 0.017 | ||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Difficulty Sleeping – Distress (n=312) | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.73 | 0.09 | 0.57–0.93 | 0.010 | ||||

| Quadratic | 1.05 | 0.03 | 1.001–1.10 | 0.046 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.64 | 0.09 | 0.48–0.83 | 0.001 | ||||

| Quadratic | 1.08 | 0.03 | 1.02–1.14 | 0.004 | ||||

| Enrollment | 0.91 | 0.05 | 0.81–1.03 | 0.123 | ||||

| Linear – cross level interaction | 1.09 | 0.04 | 1.02–1.18 | 0.021 | ||||

| Quadratic – cross-level interaction | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.97–0.996 | 0.014 | ||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Linear | 0.53 | 0.10 | 0.36–0.77 | 0.001 | ||||

| Quadratic | 1.12 | 0.04 | 1.04–1.20 | 0.003 | ||||

| Enrollment | 1.10 | 0.15 | 0.84–1.44 | 0.504 | ||||

| Linear – cross level interaction | 1.24 | 0.12 | 1.03–1.49 | 0.022 | ||||

| Quadratic – cross-level interaction | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.93–0.99 | 0.021 | ||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Change In the Way Food Tastes – Distress (n=271) | ||||||||

| Piecewise model | ||||||||

| P1 assessments | 1.36 | 0.29 | 0.90–2.07 | 0.148 | ||||

| P2 assessments | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.28–0.87 | 0.014 | ||||

| P3 assessments | 2.94 | 0.92 | 1.59–5.43 | 0.001 | ||||

| P4 assessments | 0.31 | 0.13 | 0.14–0.71 | 0.005 | ||||

| Treatment group | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of metastatic sites | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Time from cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Number of prior cancer treatments | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

| Chemotherapy regimen | ||||||||

| Enrollment | NS | |||||||

| Cross-level interaction | NS | |||||||

CI = confidence interval; NS = not significant; OR = odds ratio; P1 = enrollment to time 2; P2 = time 2 to time 3; P3 = time 4 to time 5; P4 = time 5 to time 6; SE = standard error

Figure 1.

Observed (open circles) and predicted (filled circles) trajectories for the probability of occurrence of pain (a), lack of energy (c), and nausea (d) across the six assessments. Observed and predicted trajectories for the occurrence of pain across the six assessments for patients with colon, rectal, and anal cancers versus patients with all other gastrointestinal (GI) cancers (b).

Figure 2.

Observed (open circles) and predicted (filled circles) trajectories for the probability of occurrence of feeling drowsy (a), numbness/tingling in hands/feet (b), difficulty sleeping (c), and change in the way food tastes (d) across the six assessments.

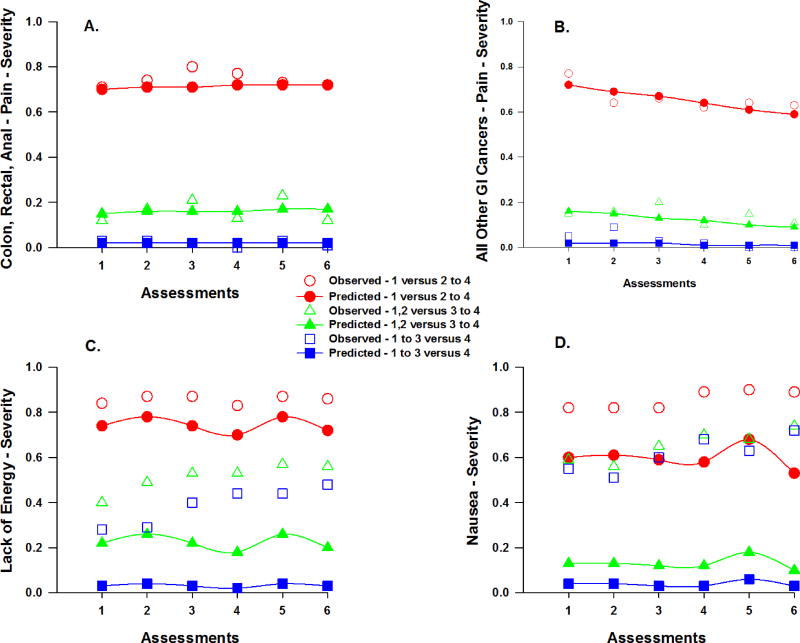

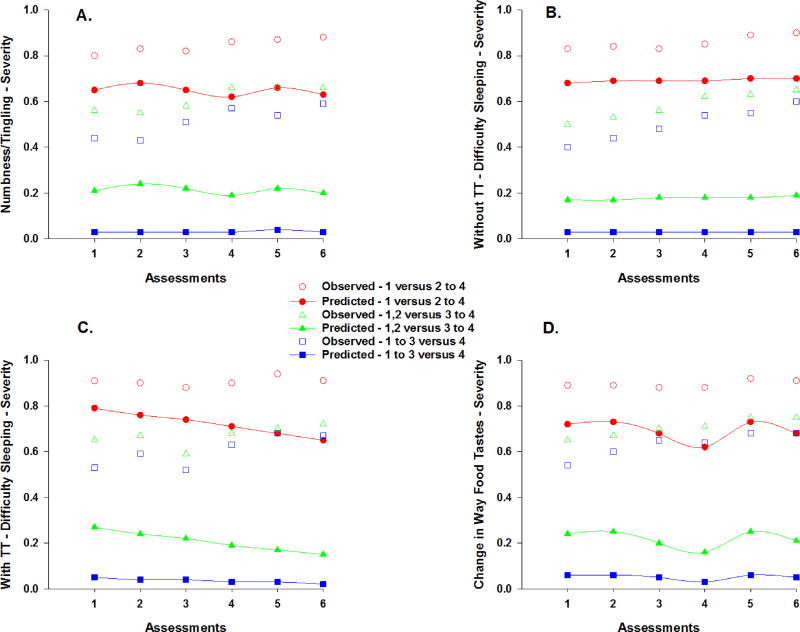

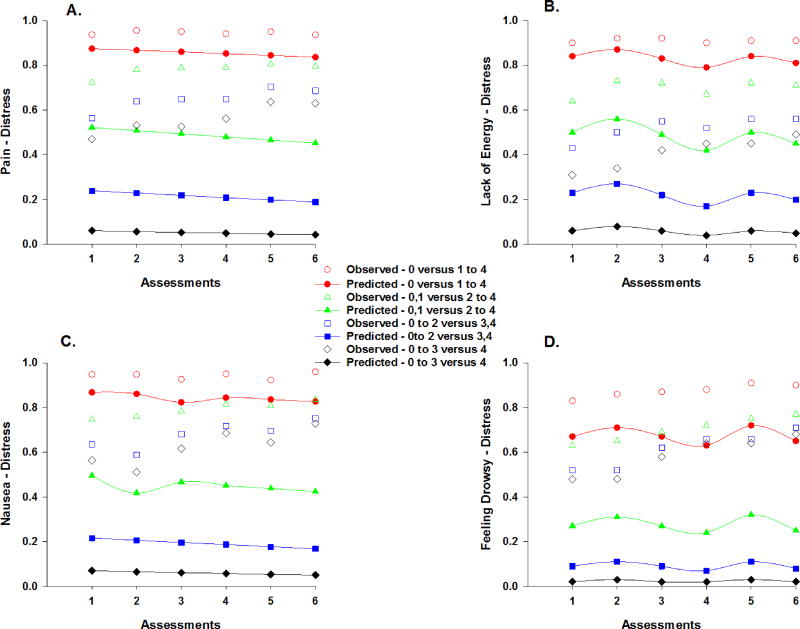

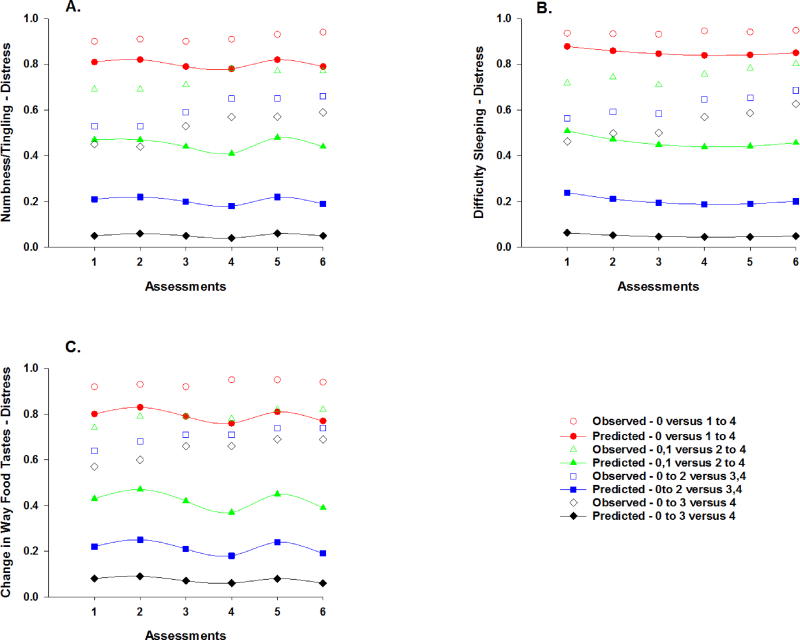

The figures that illustrate the unconditional and conditional models for the severity (Figures 3 and 4) and distress (Figures 5 and 6) ratings for the various symptoms can be interpreted as the probabilities that a patient would give a rating for a higher value or values, compared to the lower value(s) on the ordinal symptom severity or distress scales. For example, for severity, one line displays the predicted probability that a patient would give a rating of 2, 3, or 4, compared to 1. A second line in the plot displays the probability that a patient would respond 3 or 4, compared to 1 or 2, and so forth. For the same figure, the observed plots show the cumulative proportions of responding 1 compared to 2–4, a second line for the cumulative proportions of responding 1 or 2 compared to 3 to 4, and a third line for the cumulative proportions of responding 1, 2, or 3 compared to 4. The computed probabilities for each plot are based on either the linear effect, or the linear and quadratic effects of time, or the piecewise coefficients for the change over time given multiple “bends” in the trajectory due to the two treatment cycles.

Figure 3.

Observed and predicted trajectories for the probability of a reporting a higher versus a lower severity rating for pain across the six assessments for patients with colon, rectal, and anal cancers (a) versus patients with all other gastrointestinal (GI) cancers (b). Observed and predicted trajectories for the probability of a higher versus a lower severity rating for lack of energy (c) and nausea (d) across the six assessments. Severity ratings are plotted as observed (open circles) and predicted (filled symbols) values for slight versus moderate to very severe (1 versus 2 to 4), slight/moderate versus severe/very severe (1,2 versus 3 to 4), and slight to severe versus very severe (1 to 3 versus 4).

Figure 4.

Observed and predicted trajectories for the probability of a higher versus a lower severity rating for numbness/tingling in the hands/feet (a) and change in the way food tastes (d) across the six assessments. Observed and predicted trajectories for the probability of a reporting a higher versus a lower severity rating for difficulty sleeping across the six assessments for patients who did not (b) and did (c) received targeted therapy (TT) with their chemotherapy. Severity ratings are plotted as observed (open circles) and predicted (filled symbols) values for slight versus moderate to very severe (1 versus 2 to 4), slight/moderate versus severe/very severe (1,2 versus 3 to 4), and slight to severe versus very severe (1 to 3 versus 4).

Figure 5.

Observed and predicted trajectories for the probability of a higher versus a lower distress rating for pain (a), lack of energy (b), nausea (c), and feeling drowsy (d) across the six assessments. Distress ratings are plotted as observed (open circles) and predicted (filled symbols) values for not at all versus a little bit to very much (0 versus 1 to 4), not at all/a little bit versus somewhat to very much (0,1 versus 2 to 4), not at all to somewhat versus quite a bit/very much (0 to 2 versus 3,4), and not at all to quite a bit versus very much (0 to 3 versus 4).

Figure 6.

Observed and predicted trajectories for the probability of a higher versus a lower distress rating for numbness/tingling in hands/feet (a), difficulty sleeping (b), and change in the way food tastes (c) across the six assessments. Distress ratings are plotted as observed (open circles) and predicted (filled symbols) values for not at all versus a little bit to very much (0 versus 1 to 4), not at all/a little bit versus somewhat to very much (0,1 versus 2 to 4), not at all to somewhat versus quite a bit/very much (0 to 2 versus 3,4), and not at all to quite a bit versus very much (0 to 3 versus 4).

Pain

Approximately 60% of patients reported pain before their next dose of CTX (i.e., T1). As illustrated in Figure 1a, occurrence rates for pain displayed a linear decrease after T1 through T6 (odds ratio [OR] = 0.91), which was attenuated by a 9% decrease in the odds of reporting the occurrence of pain (Table 2). Age, time from cancer diagnosis, and number of prior cancer treatments were associated with the occurrence of pain at enrollment. For each additional year of age, the odds of reporting pain decreased by 6%. For each additional year from the patients’ cancer diagnosis, the odds of reporting pain were 1.13 times more likely. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of reporting pain were 1.80 times more likely. In addition, a cross-level interaction with cancer diagnosis (i.e., colon, rectal, or anal [i.e., CRC group] versus other GI cancers) was significant (Figure 1b). For each additional assessment, the odds of reporting pain decreased by 16% for patients in the CRC group compared to patients with other GI cancers.

Severity ratings for pain did not change over time (Table 3). However, number of prior cancer treatments was associated with the severity of pain at enrollment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the pain severity scale were 1.32 times more likely. In addition, the cross-level interaction with cancer diagnosis was significant (Figures 3a and 3b). For each additional assessment, the odds of moving one point higher on the pain severity scale increased by 27% for patients in the CRC group compared to those with other types of GI cancers.

Distress ratings for pain changed over time (Table 4). As illustrated in Figure 5a, for each additional assessment, the odds of moving one point higher on the pain distress scale decreased by 10%. Only number of prior cancer treatments was associated with pain distress at enrollment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the pain distress scale were 1.29 times more likely. In addition, the cross-level interaction with time from cancer diagnosis was significant. For each additional assessment, as the year from the patients’ cancer diagnosis increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the pain distress scale were 1.03 times more likely.

Lack of Energy

Approximately, 80% of patients reported lack of energy before their next dose of CTX (i.e., T1). As illustrated on Figure 1c, occurrence rates for lack of energy displayed a linear decrease after T1 through T6 (OR = 0.91), which was attenuated by a 9% decrease in the odds of reporting the occurrence of lack of energy (Table 2). Age and time from cancer diagnosis were associated with the occurrence of lack of energy at enrollment. For each additional year of age, the odds of reporting lack of energy decreased by 3%. For each additional year from the patients’ cancer diagnosis, the odds of reporting lack of energy were 1.17 times more likely. In addition, a cross-level interaction with CTX regimen was significant. For each additional assessment, patients who received FOLFIRINOX were 1.47 times more likely to report lack of energy compared to patients who received FOLFOX.

Severity ratings for lack of energy changed over time (Table 3). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 3c, the odds of moving one point higher on the lack of energy severity scale were 1.56 times greater from piecewise segment T1 to T2, decreased by 59% from piecewise segment T2 to T3, were 3.56 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5, and decreased by 77% from piecewise segment T5 to T6. Number of prior cancer treatments was associated with the severity of lack of energy at enrollment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the lack of energy severity scale were 1.33 times more likely. In addition, the cross level interaction with time from cancer diagnosis was significant. For each additional assessment, as the year from the patients’ cancer diagnosis increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the lack of energy severity scale were 1.28 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5.

Distress ratings for lack of energy changed over time (Table 4). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 5b, the odds of moving one point higher on the lack of energy distress scale were 1.47 times greater from piecewise segment T1 to T2, decreased by 59% from piecewise segment T2 to T3, were 2.85 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5, and decreased by 57% from piecewise segment T5 to T6. Only number of prior cancer treatments was associated with the distress from lack of energy at enrollment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the lack of energy distress scale were 1.27 times more likely.

Nausea

Approximately 51% of the patients reported nausea before their next dose of CTX (i.e., T1). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 1d, occurrence rates for nausea displayed a 1.68 increase in the odds from piecewise segment T1 to T2, a decrease in the odds of 68% from piecewise segment T2 to T3, a 4.47 increase in the odds from piecewise segment T4 to T5, and a decrease in the odds of 85% from piecewise segment T5 to T6 (Table 2). Age was associated with the occurrence of nausea at enrollment. For each additional year of age, the odds of reporting nausea decreased by 6%.

Severity ratings for nausea changed over time (Table 3). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 3d, the odds of moving one point higher on the nausea severity scale were 2.68 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5 and decreased by 86% from piecewise segment T5 to T6. Age was associated with the severity of nausea at enrollment. For each additional year of age, the odds of moving one point higher on the nausea severity scale decreased by 4%.

Distress ratings for nausea changed over time (Table 4). As illustrated in Figure 5c, for each additional assessment, the odds of moving one point higher on the nausea distress scale decreased by 10%. None of the covariates were associated with the distress ratings for nausea at enrollment or exhibited cross-level interactions.

Feeling Drowsy

Approximately 58% of the patients reported feeling drowsy before their next dose of CTX (i.e., T1). As illustrated in Figure 2a, occurrence rates for feeling drowsy displayed a linear decrease after T1 through T6 (OR = 0.85) that was attenuated by a 15% decrease in the odds of reporting the occurrence of feeling drowsy (Table 2). Only treatment group was associated with the occurrence of feeling drowsy at enrollment. The odds of reporting feeling drowsy decreased by 53% for patients who received CTX with TT.

Severity ratings for feeling drowsy did not change over time (Table 3). However, age was associated with the severity of feeling drowsy at enrollment. For each additional year of age, the odds of moving one point higher on the feeling drowsy severity scale decreased by 2%.

Distress ratings for feeling drowsy changed over time (Table 4). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 5d, the odds of moving one point higher on the feeling drowsy distress scale decreased by 47% from piecewise segment T2 to T3, were 2.61 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5, and decreased by 70% from piecewise segment T5 to T6. None of the covariates were associated with the distress ratings for feeling drowsy at enrollment or exhibited cross-level interactions.

Numbness/Tingling in Hands/Feet

Approximately 63% of the patients reported numbness/tingling in hands/feet before their next dose of CTX (i.e., T1). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 2b, occurrence rates for numbness/tingling in hands/feet displayed a decrease in the odds of 48% from piecewise segment T2 to T3, a 2.45 increase in the odds from piecewise segment T4 to T5, and a decrease in the odds of 59% from piecewise segment T5 to T6 (Table 2). Number of metastatic sites, cancer diagnosis, and CTX regimen were associated with the occurrence of numbness/tingling in hands/feet at enrollment. As the number of metastatic sites increased, the odds of reporting numbness/tingling in hands/feet decreased by 28%. The odds of reporting numbness/tingling in hands/feet were 2.16 times greater for patients in the CRC group. Patients who received FOLFOX were 9.70 times more likely to report numbness/tingling in hands/feet compared to patients who received FOLFIRI. In addition, patients who received other combinations of CTX were 89% less likely to report numbness/tingling in hands/feet compared to patients who received FOLFOX. A cross level interaction was detected for age and the occurrence of numbness and tingling in the hands and feet. For each additional assessment, as the patients’ age increased by one year, the odds of reporting pain decreased by 6% between piecewise segment T4 and T5.

Severity ratings for numbness/tingling in hands/feet changed over time (Table 3). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 4a, the odds of moving one point higher on the numbness/tingling in hands/feet severity scale decreased by 45% from piecewise segment T2 to T3 and were 2.04 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5. Number of prior treatments and cancer diagnosis were associated with the severity of numbness/tingling in hands/feet at enrollment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the numbness/tingling in hands/feet severity scale were 1.57 times more likely. The odds of moving one point higher on the numbness/tingling in hands/feet severity scale were 2.66 times greater for patients in the CRC group.

Distress ratings for numbness/tingling in hands/feet changed over time (Table 4). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 6a, the odds of moving one point higher on the numbness/tingling in hands/feet distress scale were 2.05 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5 and decreased by 55% from piecewise segment T5 to T6. Number of prior cancer treatments and cancer diagnosis were associated with the distress from numbness/tingling in hands/feet at enrollment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the numbness/tingling in hands/feet distress scale were 1.36 times more likely. The odds of moving one point higher on the numbness/tingling in hands/feet distress scale were 2.46 times greater for patients in the CRC group. In addition, a cross-level interaction with age was significant. For each additional assessment, as the patients’ age increased by one year, the odds of moving one point higher on the numbness/tingling in hands/feet distress scale were 1.03 times more likely from piecewise segment T1 to T2, decreased by 5% from piecewise segment T2 to T3, were 1.08 times more likely from piecewise segment T4 to T5, and decreased by 8% from T5 to T6.

Difficulty Sleeping

Approximately 61% of the patients reported difficulty sleeping before their next dose of CTX (i.e., T1). As illustrated in Figure 2c, occurrence rates for difficulty sleeping displayed a linear decrease after T1 through T6 (OR = 0.89), which was attenuated by an 11% decrease in the odds of reporting the occurrence of difficulty sleeping (Table 2). Treatment group, age, and number of prior cancer treatments were associated with the occurrence of difficulty sleeping at enrollment. For patients who received TT, the odds of reporting difficulty sleeping decreased by 60%. For each additional year of age, the odds of reporting difficulty sleeping decreased by 6%. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of reporting difficulty sleeping were 1.56 times more likely.

Severity ratings for difficulty sleeping did not change over time (Table 3). However, number of prior cancer treatments and CTX regimen were associated with the severity of difficulty sleeping at enrollment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the difficulty sleeping severity scale were 1.44 times more likely. In addition, patients who received FOLFIRINOX were 84% less likely to report higher severity scores for difficulty sleeping compared to patients who received FOLFIRI. In addition, a cross-level interaction with treatment group was significant (Figures 4a and 4b). For each additional assessment, the odds of moving one point higher on the difficulty sleeping severity scale decreased by 25% for patients who received CTX with TT.

Distress ratings for difficulty sleeping changed over time (Table 4). As illustrated in the quadratic model in Figure 6b, for each additional assessment, the odds of moving one point higher on the difficulty sleeping distress scale initially decreased by 27%. Then the rate of decrease was attenuated by an increase of 5% in the rate of change for each assessment (i.e., the decreasing trajectory became less steep). Cross level interactions were found for time from cancer diagnosis and number of prior cancer treatments. For each additional year from the patients’ cancer diagnosis, there was a 9% linear increase in the odds of moving one point higher on the difficulty sleeping scale together with a 2% decrease in the rate of change in the distress from difficulty sleeping for each additional assessment. As the number of prior cancer treatments increased, the odds of moving one point higher on the difficulty sleeping scale were 1.27 times more likely. In addition, as the number of prior cancer treatments increased, a 24% linear increase in the odds of moving one point higher on the scale, attenuated by a 4% decrease in the rate of change, was found in reports of difficulty sleeping for each additional assessment.

Change in the Way Food Tastes

Approximately 51% of the patients reported change in the way food tastes before their next dose of CTX (i.e., T1). As illustrated in Figure 2d, occurrence rates for change in the way food tastes displayed a linear decrease after T1 through T6 (OR = 0.91), which was attenuated by a 9% decrease in the odds of reporting the occurrence of change in the way food tastes (Table 2). Except for CTX regimen, none of the covariates were associated with the occurrence of this symptom. However, none of the post hoc contrasts for CTX regimen were significant.

Severity ratings for change in the way food tastes changed over time (Table 3). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 4d, the odds of moving one point higher on the change in the way food tastes severity scale were 3.78 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5 and decreased by 72% from piecewise segment T5 to T6. Time from cancer diagnosis was associated with the severity of this symptom at enrollment. For each additional year from the patients’ cancer diagnosis, the odds of moving one point higher on the change in the way food tastes severity scale decreased by 10%.

Distress ratings for change in the way food tastes changed over time (Table 4). As illustrated in the piecewise model in Figure 6c, the odds of moving one point higher on the change in the way food tastes distress scale decreased by 51% from piecewise segment T2 to T3, were 2.94 times greater from piecewise segment T4 to T5, and decreased by 69% from piecewise segment T5 to T6. None of the covariates were associated with distress ratings for change in the way food tastes at enrollment or exhibited cross level interactions.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate for changes over time in the occurrence, severity, and distress of seven common symptoms in GI cancer patients. Depending on the specific symptom, as well as the different dimensions of the symptom experience that were evaluated, the trajectories of these symptoms were highly variable. The various demographic and clinical characteristics, that were included in the regression analyses, provide useful information on phenotypic characteristics that were associated with a higher symptom burden. Findings for each symptom are discussed in detail in the subsequent sections of the discussion.

Pain

Consistent with previous reports,24–26 while 60% of the patients had pain at enrollment, occurrence rates for pain decreased over the two cycles of CTX. In terms of pain severity, while one study found a decrease in pain severity from the first (i.e., 3.00 in 0 to 10 NRS) to the sixth (i.e., 1.91) cycle of CTX,27 pain severity scores in our study did not change over time. This inconsistency may be related to differences in CTX regimens, GI cancer diagnoses, and/or the timing of assessments. Similar to occurrence rates, pain distress ratings decreased over time in our study. In terms of the findings regarding the influence of seven clinically meaningful covariates on the various dimensions of the pain experience, some interesting patterns were found.

Neither the receipt of TT nor the CTX regimen administered, had an effect on any dimension of the pain experience. However, the number of prior cancer treatments, but not the number of metastatic sites was associated with higher occurrence rates, as well as severity and distress ratings for pain at enrollment. While the types of cancer treatments that our patients received were representative of patients with GI cancers,28,29 previous studies in patients with cancer demonstrated that surgery [e.g., post surgical pain30], RT [e.g., enteritis, proctitis31] and CTX [e.g., neuropathy32] can result in chronic pain conditions and may have cumulative effects. While the specific etiologies for pain were not evaluated, the finding that an increased time from their cancer diagnosis, as well as increased number of cancer treatments, were associated with higher occurrence, severity, and distress ratings for pain suggests that our patients may be experiencing multiple chronic pain conditions. This hypothesis warrants investigation in future studies.

In terms of cancer diagnosis, for our analyses, patients were categorized into two groups (i.e., CRC group [colon, rectal, anal cancers] versus other GI cancers). In terms of pain occurrence, compared to patients with other GI cancers, patients in the CRC group were less likely to report the occurrence of pain. This finding is consistent with previous reports of pain in patients with a variety GI cancers,33,34 that found that occurrence rates for pain in patients with liver34 and pancreatic33 cancer ranged from 70.0% to 75.0%, respectively. In contrast, in previous studies, patients with CRC reported pain occurrence rates that ranged from 42.1%35 to 51%,36 respectively. However, in terms of pain severity, over the course of the two cycles of CTX, patients with CRC were more likely to report higher pain severity scores. This finding warrants confirmation in future studies. Finally, and consistent with previous reports,37,38 older patients were less likely to report the occurrence of pain at enrollment. However, age was not associated with differences in severity and distress ratings for pain.

Lack of Energy

Consistent with previous reports,39,40 80% of our patients reported lack of energy (i.e., proxy for fatigue on the MSAS) at enrollment. Of note, while occurrence rates decreased slightly, severity (Figure 3c) and distress (Figure 5b) ratings increased in the week following in the administration of each dose of CTX and then decreased the following week. These fluctuations in fatigue severity are consistent with a previous study of patients with CRC receiving adjuvant CTX.39

The phenotypic characteristics that influenced various dimensions of fatigue were: age, time from cancer diagnosis, number of prior cancer treatments, and the CTX regimen administered. Consistent with previous studies,6,41 younger age was associated with higher occurrence rates for fatigue. This association may be explained by age differences in the doses of CTX administered42 or by a “response shift” in older patients’ perceptions of symptoms.43,44

Similar to pain, a longer time from cancer diagnosis and receipt of a higher number of cancer treatments were associated with higher occurrence rates and/or higher severity and distress ratings for fatigue, respectively. This finding suggests that the cumulative effects of the disease and its treatments influence various dimensions of this symptom.

In terms of CTX regimen administered, compared to patients who received FOLFOX, patients who received FOLFIRINOX were approximately 1.5 times more likely to report the occurrence of fatigue. This finding may be related to the addition of irinotecan to the CTX regimen.

Nausea

Consistent with previous reports of acute nausea during CTX,45,46 over 50% of the patients reported the occurrence of nausea prior to their next dose of CTX. While distress from nausea decreased over the two cycles of CTX, occurrence (Figure 1d) and severity (Figure 3d) increased in the week following the administration of each dose of CTX and then decreased the following week. Our findings are consistent with previous studies that found that if nausea is not well controlled its occurrence and severity increases over the course of CTX.47,48 In addition, our findings suggest that a significant number of patients treated for GI cancers experience this symptom and that severity (range, 1 to 4; mean = 1.81, SD = 0.81) and distress (range, 0 to 4; mean = 1.68, SD = 1.12) ratings were at a moderate level. While most of the literature suggests that current antiemetic regimens effectively control vomiting,49,50 additional investigations are warranted on their impact on the various dimensions of nausea during CTX.

Age was the only characteristic associated with nausea. Consistent with previous reports of risk factors for CTX-induced nausea (CIN),51,52 younger patients were more likely to report the occurrence of and higher severity scores for CIN. Potential explanations for this associated risk include the fact that younger patients receive more aggressive treatment regimens, more combinations of CTX, and/or higher doses of CTX than older patients due to the increased toxicity risks.

Feeling Drowsy

Almost 60% of our patients reported the occurrence of feeling drowsy prior to their next dose of CTX. Consistent with other studies that used the MSAS to evaluate symptoms prior to or during CTX,25,26 our occurrence rate decreased over the two cycles of CTX. Possible reasons for the high occurrence of this symptom include the co-occurrence of other symptoms (e.g., pain and difficulty sleeping); medications patients were taking to decrease nausea and vomiting, pain, and/or anxiety; and/or dehydration. While severity ratings did not change over time, in the week following the administration of the first dose of CTX (i.e., T2 to T3), distress ratings for feeling drowsy decreased (Figure 5d). During the second cycle, distress ratings for feeling drowsy increased during the week following the second dose of CTX (i.e., T4 to T5) and then decreased in the subsequent week (i.e., T5 to T6). Future studies need to determine the etiologies for this symptom.

Feeling drowsy was one of two symptoms influenced by treatment regimen. Patients who received TT reported lower occurrence rates for this symptom prior to their next dose of CTX. While no study has reported on treatment group differences in this symptom in patients with GI cancers, in one study of patients with mCRC,53 fatigue scores were lower in the patients who received CTX with TT. This finding is important because previous studies found moderate to high correlations between fatigue and feeling drowsy, daytime sleepiness, and napping.54,55 Again, younger age was associated with higher severity ratings for feeling drowsy. If medications contribute to this symptom, it is known that older oncology patients take lower doses of analgesic medications56 and are less likely to take antiemetics57 and/or anti-anxiety medications.58

Numbness/Tingling in Hands/Feet