Abstract

Objective

To determine the frequency of hyperoxia and hypocapnia during pediatric ECMO and their relationships to complications, mortality and functional status among survivors.

Design

Secondary analysis of data collected prospectively by the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN).

Setting

Eight CPCCRN-affiliated hospitals.

Patients

Age <19 years and treated with ECMO.

Interventions

Hyperoxia was defined as highest PaO2 >200 Torr (27 kPa), and hypocapnia as lowest PaCO2 <30 Torr (3.9 kPa) during the first 48 hours of ECMO. Functional status at hospital discharge was evaluated among survivors using the Functional Status Scale.

Measurements and Main Results

Of 484 patients, 420 (86.7%) had venoarterial ECMO and 64 (13.2%) venovenous; 69 (14.2%) had ECMO initiated during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR). Hyperoxia occurred in 331 (68.4%) and hypocapnia in 98 (20.2%). Hyperoxic patients had higher mortality than patients without hyperoxia (167 (50.5%) vs. 48 (31.4%), p<0.001), but no difference in functional status among survivors. Hypocapnic patients were more likely to have a neurologic event (49 (50.0%) vs. 143 (37.0%), p=0.021) or hepatic dysfunction (49 (50.0%) vs. 121 (31.3%), p<0.001) than patients without hypocapnia, but no difference in mortality or functional status among survivors. On multivariable analysis, factors independently associated with increased mortality included highest PaO2 and highest blood lactate concentration in the first 48 hours of ECMO, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and being a preterm neonate. Factors independently associated with lower mortality included meconium aspiration syndrome.

Conclusions

Hyperoxia is common during pediatric ECMO and associated with mortality. Hypocapnia appears to occur less often and although associated with complications, an association with mortality was not observed.

Keywords: Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, hyperoxia, hypocapnia, child, infant, neonate

INTRODUCTION

Hyperoxia has been associated with adverse outcomes from several conditions complicated by reperfusion injury such as cardiac arrest (1–3), traumatic brain injury (4–5), and neonatal asphyxia (6). The influx of oxygen during reperfusion of ischemic tissue leads to production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by altered mitochondria and enzymes (7, 8). Hyperoxia during reperfusion may increase production of ROS, exacerbating their pathological effects. ROS cause peroxidation of lipids, denaturation of proteins and damage to DNA. The damage produced to these macromolecules can cause abnormal gene expression and impaired cellular functioning. In addition, ROS activate neutrophils and platelets leading to an exaggerated inflammatory and thrombotic cascade.

Hypocapnia has also been associated with adverse outcomes after cardiac arrest (9–12), traumatic brain injury (13–14), stroke (15) and neonatal asphyxia (6, 16). Hypocapnia may contribute to neurological injury by causing cerebral vasoconstriction, decreased cerebral blood flow, and increased cerebral ischemia (17). Some have found mild hypercapnia to be neuroprotective (11). In addition to increasing cerebral perfusion, mild hypercapnia may have anticonvulsant, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.

Investigators have begun to explore the potential impact of partial pressures of arterial oxygen (PaO2) and carbon dioxide (PaCO2) on patient outcomes after extracorporeal circulation including extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and cardiopulmonary bypass (7, 8, 18–21). Extracorporeal circulation exposes the patient’s blood to an artificial circuit, which elicits a systemic inflammatory response, and alters the redox equilibrium by increasing production of ROS (7, 8). Hyperoxia may intensify the oxidative stress elicited by circuit; however, the extent to which hyperoxia during extracorporeal circulation is associated with adverse patient outcomes is not well characterized. Similarly, little clinical data exist on the association between PaCO2 during extracorporeal circulation and patient outcomes. We hypothesize that both hyperoxia and hypocapnia during pediatric ECMO will be associated with worse patient outcomes. Our objective is to determine the frequency of hyperoxia and hypocapnia during pediatric ECMO and the relationships between these blood gas derangements and complications, mortality and functional status among survivors.

METHODS

Design and Setting

The study was a secondary analysis of data collected for the Bleeding and Thrombosis during ECMO (BATE) study (22) which aimed to describe the incidence of bleeding and thrombosis in neonatal and pediatric ECMO patients. In the BATE study, prospective observational data were collected at eight children’s hospitals affiliated with the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network between December 2012 and September 2014. The Institutional Review Boards for each hospital and the Data Coordinating Center at the University of Utah approved the study with waiver of parental permission.

Study Subjects

All patients <19 years of age treated with ECMO in a neonatal, pediatric or cardiac intensive care unit (ICU) were included in the BATE study (n=514). Only the initial ECMO course was included for patients who required multiple courses of ECMO. Three patients had no arterial blood gases collected in the first 48 hours of ECMO and were excluded from this secondary analysis. In addition, 27 patients with hypoxia (i.e., highest PaO2 <60 Torr (8 kPa) in the first 48 hours of ECMO) were excluded (see Statistical Analysis, below).

Data Collection

Trained research coordinators collected all data daily via direct observation, discussion with bedside clinicians, and review of medical records. Data included demographics; body weight; history of prematurity; acute and chronic diagnoses; occurrence of an operative procedure or cardiopulmonary bypass in the 24 hours prior to ECMO initiation; indications for ECMO; mode of ECMO; Vasoactive Inotrope Score (VIS) (23, 24) and Oxygenation Index (OI) (25) at the time of ECMO initiation; body temperature, arterial blood gases (pH, PaO2, PaCO2) and lactate concentration closest and prior to ECMO initiation (baseline); arterial blood gases, lactate concentration and ECMO blood flow rate recorded closest to 7 AM on each ECMO day; and clinical site.

Demographics included age at ECMO initiation, sex, race and ethnicity. Prematurity was <37 weeks gestational age at birth and collected for neonates only. Indications for ECMO were categorized as respiratory, cardiac or extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR). Mode of ECMO was categorized as venoarterial (VA) or venovenous (VV). VV ECMO that was converted to VA was categorized as VA ECMO. VIS (23, 24) was calculated from the hourly dose of dopamine, dobutamine, epinephrine, milrinone, vasopressin and norepinephrine administered at the time of ECMO initiation. Higher VIS scores indicate greater vasoactive and inotropic support. OI (25) was calculated from the mean airway pressure (MAP), fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), and PaO2 at the time of ECMO initiation as MAP × FiO2 × 100/PaO2. Higher OI scores indicate greater intensity of ventilator support to maintain oxygenation. Hyperoxia was defined as highest PaO2 >200 Torr (27 kPa), and hypocapnia as lowest PaCO2 <30 Torr (3.9 kPa) during the first 48 hours of ECMO (7, 26, 27). The first 48 hours of ECMO was selected in order to reflect the most vulnerable period for ischemia reperfusion injury (1, 3, 12, 18). Blood flow rate was the average blood flow rate in mL/kg/min over the first 48 hours of ECMO.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Other outcomes included complications during ECMO; duration of ECMO, and ICU and hospital stay; and functional status at hospital discharge among survivors. Complications included bleeding events, thrombotic events, neurologic events, hepatic dysfunction, and renal failure. Bleeding events were defined as blood loss requiring a transfusion or intracranial hemorrhage. Thrombotic events included intracranial infarction, limb ischemia, pulmonary embolus, intracardiac thrombus, aorto-pulmonary shunt thrombus, other sites of thrombosis, and circuit thrombosis requiring replacement of a circuit component. Neurologic events included seizures (clinical or electrographic), intracranial hemorrhage or infarction, and brain death. Hepatic dysfunction was defined as an International Normalized Ratio (INR) >2. Renal failure was defined as a creatinine concentration >2 mg/dL (>176.8 μmol/L) or use of renal replacement therapy. Functional status at hospital discharge was evaluated among survivors using the Functional Status Scale (FSS) (28). The FSS assesses function in six domains: mental, sensory, communication, motor, feeding and respiratory. Total FSS scores range from 6–30 and are categorized as 6–7 (good), 8–9 (mildly abnormal), 10–15 (moderately abnormal), 16–21 (severely abnormal) and >21 (very severely abnormal).

Statistical Analysis

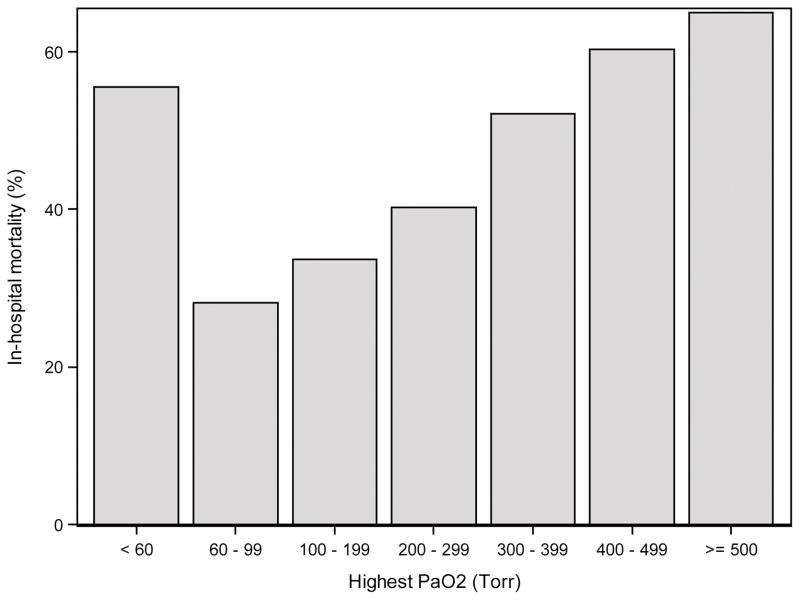

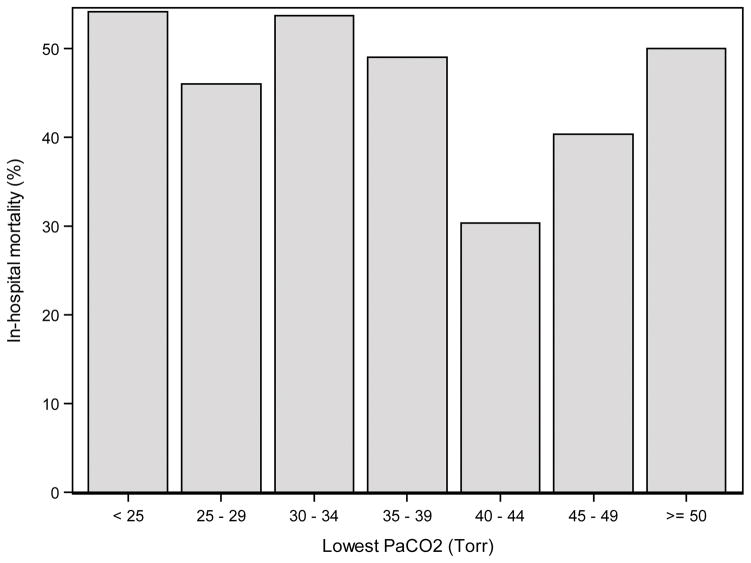

The relationship of hyperoxia and hypocapnia to pre-ECMO patient characteristics and outcomes was assessed with Fisher’s exact test for nominal variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for ordinal variables. Prior to developing logistic regression models of in-hospital mortality, the relationship of highest PaO2 and lowest PaCO2 in the first 48 hours of ECMO to mortality was explored using bar charts (Figures 1 and 2). PaCO2 did not appear to have a strong relationship with mortality, but there was some tendency toward higher mortality with both low and high PaCO2 and lower mortality with moderate PaCO2. Therefore, PaCO2 could not be included as an interval predictor. Instead, a nominal variable was created with three levels, PaCO2 <30 Torr (3.9 kPa), 30–50 Torr (3.9–6.6 kPa) and >50 Torr (>6.6 kPa). PaO2 was found to have a strong linear relationship with mortality, with higher PaO2 predicting a higher risk of mortality. The only exception to this was the 27 hypoxic patients (PaO2 <60 Torr (<8 kPa)) who also had a high mortality rate. Rather than discretize PaO2 into a few levels, the 27 hypoxic patients were excluded from the analyses. This allowed PaO2 to be included as an interval variable so that the model could take full advantage of the strong linear relationship.

Figure 1.

In-hospital mortality by the highest PaO2 in the first 48 hours of ECMO.

Figure 2.

In-hospital mortality by the lowest PaCO2 in the first 48 hours of ECMO.

Mortality was modeled with univariable logistic regression in order to identify potential predictors. Variables associated with mortality in univariable models (p < 0.20) were considered potential predictors if data were missing for less than 10% of the cohort. The branch-and-bound algorithm of Furnival and Wilson (29) was used to identify the subset of potential predictors that generate the multivariable logistic regression model with the best penalized fit in terms of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Only models that included the primary variables of interest, PaO2 and PaCO2, were considered. In this way, the primary predictors were forced into the multivariable models. In addition to the subset of predictors achieving the best penalized fit, one additional model was within 2 points of this BIC. These two models are regarded as statistically equivalent in terms of penalized fit. Since both models achieved equivalent penalize fit, the authors selected the model with the most clinically relevant predictors as the final multivariable model. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute; Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Of 484 patients included in the study, 48 (9.9%) were preterm neonates, 209 (43.2%) full-term neonates, and 227 (46.9%) infants, children and adolescents (Table 1). Two hundred and eighty (57.9%) were male, and 239 (49.4%) were White. Three hundred and thirty-one (68.4%) had hyperoxia and 98 (20.2%) had hypocapnia during the first 48 hours of ECMO. Median highest PaO2 was 261 Torr (IQR 155, 364) (35 kPa (IQR 20, 48)) and median lowest PaCO2 was 37 Torr (IQR 31, 43) (4.9 kPa (IQR 4.1, 5.7)) during the first 48 hours of ECMO. Two hundred and fifteen (44.4%) patients died.

Table 1.

Description of pre-ECMO characteristics by hyperoxia and hypocapnia

| Characteristic | Hyperoxia (PaO2 > 200 mmHg)

|

Hypocapnia (PaCO2 < 30 mmHg)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 153) | Yes (N = 331) | P-value | No (N = 386) | Yes (N = 98) | P-value | |

| Age | 0.052a | 0.003a | ||||

| pre-term neonate | 16 (10.5%) | 32 (9.7%) | 33 (8.5%) | 15 (15.3%) | ||

| full-term neonate | 78 (51.0%) | 131 (39.6%) | 155 (40.2%) | 54 (55.1%) | ||

| infant | 27 (17.6%) | 82 (24.8%) | 95 (24.6%) | 14 (14.3%) | ||

| child | 17 (11.1%) | 60 (18.1%) | 65 (16.8%) | 12 (12.2%) | ||

| adolescent | 15 (9.8%) | 26 (7.9%) | 38 (9.8%) | 3 (3.1%) | ||

| Weight (kg) | 3.5 [3.0, 5.9] | 3.9 [3.0, 8.8] | 0.268b | 3.9 [3.0, 9.9] | 3.2 [2.8, 4.0] | <.001b |

| Male | 93 (60.8%) | 187 (56.5%) | 0.428a | 230 (59.6%) | 50 (51.0%) | 0.137a |

| Race | 0.564a | 0.004a | ||||

| Unknown/Not Reported | 50 (32.7%) | 82 (24.8%) | 101 (26.2%) | 31 (31.6%) | ||

| Black or African American | 22 (14.4%) | 66 (19.9%) | 69 (17.9%) | 19 (19.4%) | ||

| White | 74 (48.4%) | 165 (49.8%) | 202 (52.3%) | 37 (37.8%) | ||

| Other | 7 (4.6%) | 18 (5.4%) | 14 (3.6%) | 11 (11.2%) | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 23 (15.0%) | 61 (18.4%) | 0.308a | 68 (17.6%) | 16 (16.3%) | 0.520a |

| Primary ECMO indication | <.001a | <.001a | ||||

| Respiratory | 99 (64.7%) | 116 (35.0%) | 182 (47.2%) | 33 (33.7%) | ||

| Cardiac | 38 (24.8%) | 162 (48.9%) | 161 (41.7%) | 39 (39.8%) | ||

| ECPR | 16 (10.5%) | 53 (16.0%) | 43 (11.1%) | 26 (26.5%) | ||

| Mode of ECMO | <.001a | 0.131a | ||||

| Venoarterial | 115 (75.2%) | 305 (92.1%) | 330 (85.5%) | 90 (91.8%) | ||

| Venovenous | 38 (24.8%) | 26 (7.9%) | 56 (14.5%) | 8 (8.2%) | ||

| Clinical Site | 0.017a | <.001a | ||||

| A | 29 (19.0%) | 35 (10.6%) | 49 (12.7%) | 15 (15.3%) | ||

| B | 36 (23.5%) | 63 (19.0%) | 77 (19.9%) | 22 (22.4%) | ||

| C | 10 (6.5%) | 25 (7.6%) | 14 (3.6%) | 21 (21.4%) | ||

| D | 17 (11.1%) | 44 (13.3%) | 50 (13.0%) | 11 (11.2%) | ||

| E | 19 (12.4%) | 36 (10.9%) | 50 (13.0%) | 5 (5.1%) | ||

| F | 17 (11.1%) | 46 (13.9%) | 54 (14.0%) | 9 (9.2%) | ||

| G | 2 (1.3%) | 26 (7.9%) | 19 (4.9%) | 9 (9.2%) | ||

| H | 23 (15.0%) | 56 (16.9%) | 73 (18.9%) | 6 (6.1%) | ||

| Acute diagnoses | ||||||

| Airway abnormality | 5 (3.3%) | 6 (1.8%) | 0.336a | 9 (2.3%) | 2 (2.0%) | 1.000a |

| Immune dysfunction | 4 (2.6%) | 28 (8.5%) | 0.017a | 27 (7.0%) | 5 (5.1%) | 0.651a |

| Cardiac Arrest | 13 (8.5%) | 34 (10.3%) | 0.622a | 39 (10.1%) | 8 (8.2%) | 0.703a |

| Cardiovascular disease (acquired) | 7 (4.6%) | 56 (16.9%) | <.001a | 55 (14.2%) | 8 (8.2%) | 0.131a |

| Cardiovascular disease (arrhythmia) | 1 (0.7%) | 17 (5.1%) | 0.017a | 9 (2.3%) | 9 (9.2%) | 0.004a |

| Cardiovascular disease (congenital) | 46 (30.1%) | 141 (42.6%) | 0.009a | 137 (35.5%) | 50 (51.0%) | 0.005a |

| Hypoxic/anoxic injury | 3 (2.0%) | 14 (4.2%) | 0.290a | 14 (3.6%) | 3 (3.1%) | 1.000a |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 5 (3.3%) | 14 (4.2%) | 0.802a | 14 (3.6%) | 5 (5.1%) | 0.559a |

| Pertussis or Sepsis | 31 (20.3%) | 50 (15.1%) | 0.190a | 62 (16.1%) | 19 (19.4%) | 0.450a |

| Pneumonia or bronchiolitis | 9 (5.9%) | 11 (3.3%) | 0.220a | 20 (5.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.019a |

| Shock (non-septic) | 3 (2.0%) | 11 (3.3%) | 0.564a | 12 (3.1%) | 2 (2.0%) | 0.745a |

| Respiratory distress/failure | 53 (34.6%) | 103 (31.1%) | 0.465a | 132 (34.2%) | 24 (24.5%) | 0.070a |

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | 24 (15.7%) | 18 (5.4%) | <.001a | 35 (9.1%) | 7 (7.1%) | 0.689a |

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia | 17 (11.1%) | 38 (11.5%) | 1.000a | 43 (11.1%) | 12 (12.2%) | 0.724a |

| Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn | 38 (24.8%) | 45 (13.6%) | 0.003a | 67 (17.4%) | 16 (16.3%) | 0.882a |

| Renal failure | 4 (2.6%) | 8 (2.4%) | 1.000a | 11 (2.8%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.474a |

| Neurologic condition | 5 (3.3%) | 10 (3.0%) | 1.000a | 9 (2.3%) | 6 (6.1%) | 0.093a |

| Chronic diagnoses | ||||||

| Immune dysfunction | 1 (0.7%) | 12 (3.6%) | 0.072a | 13 (3.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.081a |

| Congenital anomaly or chromosomal defect | 34 (22.2%) | 77 (23.3%) | 0.907a | 86 (22.3%) | 25 (25.5%) | 0.503a |

| Neurologic condition | 4 (2.6%) | 20 (6.0%) | 0.120a | 23 (6.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.063a |

| Cardiovascular disease (congenital) | 30 (19.6%) | 60 (18.1%) | 0.707a | 74 (19.2%) | 16 (16.3%) | 0.564a |

| Chronic lung disease | 7 (4.6%) | 9 (2.7%) | 0.286a | 16 (4.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.051a |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) in the 24 hours prior | 26 (17.0%) | 117 (35.3%) | <.001a | 107 (27.7%) | 36 (36.7%) | 0.084a |

| Operative procedure in the 24 hours prior | 35 (22.9%) | 136 (41.1%) | <.001a | 130 (33.7%) | 41 (41.8%) | 0.155a |

| Vasoactive inotropic score | 0.111a | 0.661a | ||||

| None | 38 (24.8%) | 111 (33.5%) | 116 (30.1%) | 33 (33.7%) | ||

| Low | 48 (31.4%) | 102 (30.8%) | 123 (31.9%) | 27 (27.6%) | ||

| High | 67 (43.8%) | 118 (35.6%) | 147 (38.1%) | 38 (38.8%) | ||

| Oxygenation index | 35.3 [24.0, 53.7] | 19.8 [7.8, 41.3] | <.001b | 29.2 [12.4, 51.3] | 16.0 [7.5, 36.4] | 0.005b |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 3.1 [1.6, 7.4] | 4.4 [1.8, 9.1] | 0.052b | 3.9 [1.8, 8.0] | 4.5 [1.7, 8.8] | 0.717b |

| pH | 7.25 [7.14, 7.33] | 7.29 [7.14, 7.38] | 0.032b | 7.27 [7.14, 7.37] | 7.32 [7.19, 7.38] | 0.048b |

| Temperature (Celsius) | 36.7 [36.0, 37.1] | 36.6 [36.0, 37.1] | 0.797b | 36.7 [36.0, 37.1] | 36.7 [36.2, 37.1] | 0.684b |

P-value is based on Fisher’s exact test.

Values represent median and interquartile range; P-value is based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Hyperoxia

Patients with hyperoxia were more likely to have a cardiac indication for ECMO, receive VA ECMO, have an acute diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (acquired, congenital or arrhythmia), have an acute diagnosis of immune dysfunction, and receive cardiopulmonary bypass and/or an operative procedure in the 24 hours prior to ECMO than patients without hyperoxia (Table 1). Patients with hyperoxia were less likely to have meconium aspiration syndrome or persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn than patients without hyperoxia. Baseline OI was lower, and pH was higher in patients with hyperoxia compared to those without hyperoxia. Average ECMO blood flow rate in the first 48 hours of ECMO was higher in patients with hyperoxia than those without hyperoxia (106 [88, 127] mL/kg/min vs. 101 [80, 118] mL/kg/min, p=0.039). Hyperoxia was also associated with clinical site.

Patients with hyperoxia had higher mortality than patients without hyperoxia, and shorter durations of ECMO and ICU stay (Table 2). The shorter durations were not related to early death on ECMO for hyperoxic patients (Supplemental Digital Content 1). Among survivors, functional status at hospital discharge did not differ between those with and without hyperoxia.

Table 2.

Complications and outcomes by hyperoxia and hypocapnia

| Complication | Hyperoxia (PaO2 > 200 Torr) (> 27 kPa)

|

Hypocapnia (PaCO2 < 30 Torr) (< 3.9 kPa)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 153) | Yes (N = 331) | P-value | No (N = 386) | Yes N = 98) | P-value | |

| Duration of ECMO (days) | 5.9 [3.1, 10.5] | 4.7 [2.5, 8.0] | 0.009a | 5.2 [2.8, 9.5] | 4.2 [2.5, 6.8] | 0.050a |

| Length of ICU Stay (days) | 30.5 [15.6, 54.0] | 25.0 [12.8, 48.2] | 0.045a | 27.9 [14.3, 51.4] | 25.7 [10.0, 47.8] | 0.391a |

| Length of Hospital Stay (days) | 39.1 [19.7, 64.8] | 33.2 [13.4, 67.5] | 0.130a | 36.3 [17.0, 66.4] | 31.6 [11.1, 69.9] | 0.231a |

| Bleeding eventb | 103 (67.3%) | 240 (72.5%) | 0.282c | 271 (70.2%) | 72 (73.5%) | 0.619c |

| Thrombotic eventb | 58 (37.9%) | 125 (37.8%) | 1.000c | 149 (38.6%) | 34 (34.7%) | 0.560c |

| Neurologic eventb | 53 (34.6%) | 139 (42.0%) | 0.135c | 143 (37.0%) | 49 (50.0%) | 0.021c |

| Hepatic organ failureb | 44 (28.8%) | 126 (38.1%) | 0.052c | 121 (31.3%) | 49 (50.0%) | <.001c |

| Renal organ failureb | 54 (35.3%) | 117 (35.3%) | 1.000c | 135 (35.0%) | 36 (36.7%) | 0.813c |

| In-hospital mortality | 48 (31.4%) | 167 (50.5%) | <.001c | 166 (43.0%) | 49 (50.0%) | 0.255c |

| Functional status at hospital discharge (among survivors) | 0.296a | 0.295a | ||||

| Good | 40 (38.1%) | 44 (26.8%) | 72 (32.7%) | 12 (24.5%) | ||

| Mildly abnormal | 35 (33.3%) | 71 (43.3%) | 86 (39.1%) | 20 (40.8%) | ||

| Moderately abnormal | 22 (21.0%) | 43 (26.2%) | 52 (23.6%) | 13 (26.5%) | ||

| Severely abnormal | 7 (6.7%) | 6 (3.7%) | 10 (4.5%) | 3 (6.1%) | ||

| Very severely abnormal | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | ||

Values represent median and interquartile range; P-value is based on the Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Complications occurred on at least one study day.

Values represent absolute count and percentage based on column totals; P-value is based on Fisher’s exact test.

Hypocapnia

Patients with hypocapnia were more likely to be neonates, receive ECPR, and have an acute diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (congenital or arrhythmia) (Table 1). Patients with hypocapnia were less likely to be White or have an acute diagnosis of pneumonia or bronchiolitis than those without hypocapnia. Body weight and baseline OI were lower, and baseline pH higher in patients with hypocapnia compared to those without hypocapnia. Hypocapnia was also associated with clinical site.

Patients with hypocapnia were more likely to have a neurologic event and hepatic dysfunction than patients without hypocapnia (Table 2). Patients with hypocapnia had shorter duration of ECMO. Mortality did not differ between patients with and without hypocapnia, nor did functional status at hospital discharge among survivors.

Mortality

Patient factors associated with in-hospital mortality on univariable analyses (p<0.2 and less than 10% missing data) included the highest PaO2 and lactate, and lowest pH in the first 48 hours of ECMO, mode of ECMO, cardiovascular disease (congenital), pneumonia or bronchiolitis, meconium aspiration syndrome, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn, renal failure, neurologic condition, congenital anomaly or chromosomal defect, cardiopulmonary bypass and/or operative procedures in the 24 hours prior to ECMO, age, indication for ECMO, and average ECMO blood flow rate in the first 48 hours of ECMO (Supplemental Digital Content 2). Using multivariable analysis, factors independently associated with increased mortality included highest PaO2 and highest blood lactate concentration in the first 48 hours of ECMO, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and being a preterm neonate (Table 3; also see Supplemental Digital Content 3). Factors independently associated with lower mortality included meconium aspiration syndrome.

Table 3.

Multivariable model of in-hospital mortality

| Characteristic | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| HighestaPaO2 (10 Torr) (1.3kPa) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | <.001 |

| LowestaPaCO2 | 0.695 | |

| < 30 Torr (< 3.9 kPa) | 0.81 (0.47, 1.37) | |

| 30 – 50 Torr (3.9–6.6 kPa) | Reference | |

| > 50 Torr (> 6.6 kPa) | 0.83 (0.34, 2.00) | |

| Highestalactate (mmol/L) | 1.13 (1.09, 1.17) | <.001 |

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | 0.09 (0.02, 0.42) | 0.002 |

| Pre-term neonate | 2.97 (1.42, 6.21) | 0.004 |

| Congenital diaphragmatic hernia | 2.12 (1.10, 4.09) | 0.025 |

Extremum for each subject is assessed over the 48 hours after ECMO initiation.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that hyperoxia is common during pediatric ECMO and independently associated with increased in-hospital mortality. The frequency of hyperoxia observed in our study is similar to that reported in a smaller retrospective cohort of infants treated with VA ECMO after congenital heart disease surgery (18). This prior study found 78% of infants had hyperoxia (PaO2 >193 Torr) in the first 48 hours of ECMO. Our finding of higher in-hospital mortality among hyperoxic ECMO patients is also consistent with the prior study’s finding of higher 30-day post-operative mortality (18). A recent adult ECMO study also found a relationship between moderate hyperoxia (PaO2 101–300 Torr) and mortality (30).

The pathophysiology underlying the increase in mortality among ECMO patients with hyperoxia may be related to increased generation of ROS after a period of tissue ischemia (7, 8). During reperfusion, ROS pathologically activate neutrophils and platelets (7). Activated neutrophils display increased adhesion to damaged endothelium causing microvascular blockage and induce the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Activated platelets display increased aggregation and potential for thrombosis. Despite these known effects, we did not find a significant association between hyperoxia and thrombosis, bleeding, neurologic events, hepatic dysfunction or renal failure. The lack of association suggests direct injury to these organs from hyperoxia is not responsible for the increased mortality, or that our global assessments of organ dysfunction are inadequate to detect these cellular and microvascular changes. Another possibility is that hyperoxia during ECMO may be a marker of poor cardiac output making the relative oxygen delivery from the ECMO circuit high. Thus, increased mortality with hyperoxia could be due to myocardial failure with relatively little patient cardiac output to mix with the highly oxygenated circuit flow. Average ECMO blood flow in the first 48 hours of ECMO was somewhat higher in hyperoxic than non-hyperoxic patients; however, ECMO blood flow was not an independent predictor of mortality in our multivariable model.

Hyperoxic patients had a shorter duration of ECMO and ICU stay than non-hyperoxic patients. These findings were not due to early death on ECMO for hyperoxic patients. The shorter durations could be related to the higher number of patients in the hyperoxia group who were placed on VA ECMO for a cardiac indication. Cardiovascular patients in general have shorter ECMO runs than respiratory failure patients (31). Functional status at hospital discharge did not differ among survivors with and without hyperoxia. This finding may be due to a lack of pre-illness functional status assessment, and thus, our inability to adjust discharge functional status for pre-existing disabilities.

Hypocapnia occurred less often in our study than hyperoxia, and although associated with complications, it was not associated with mortality or functional status among survivors. Patients with hypocapnia were more likely to have a neurologic event. Hypocapnia may cause cerebral vasoconstriction, decreased cerebral blood flow and increased cerebral ischemia (17). ECMO itself alters cerebral autoregulation (32) and cerebral blood flow velocity (33), and the degree of decline in PaCO2 at initiation of ECMO has been associated with mortality (34). Patients with hypocapnia were also more likely to develop hepatic dysfunction. The cellular and biochemical derangements that occur during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury are diverse and complex (35). Whether the association between hypocapnia and hepatic dysfunction observed in our study represents a unique effect of hypocapnia on the liver or a spurious finding is unknown.

Our findings differ from prior studies demonstrating an association between hypocapnia and mortality after pediatric cardiac arrest and traumatic brain injury (12, 13). In these conditions, hypocapnia is produced by excessive mechanical ventilation rather than by the sweep gas in the ECMO circuit. Increased intrathoracic pressure from mechanical ventilation may decrease venous return and coronary perfusion pressure contributing to higher mortality (17, 36). Carbon dioxide is relatively easy to clear on ECMO and the “cost” of clearance may be less than for mechanically ventilated patients. Overall, our findings suggest both hyperoxia and hypocapnia be avoided during pediatric ECMO. This may be accomplished by judicious use of oxygen and careful attention to sweep gas flow rate to blood flow rate ratio.

Other patient factors independently associated with increased mortality in our study included higher blood lactate concentration in the first 48 hours of ECMO, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and being a preterm neonate. Meconium aspiration was independently associated with decreased mortality. These findings are consistent with previous reports (31, 37).

Strengths of this study include the multisite design and daily prospective data collection. Limitations include recording only the blood gas values closest to 7 AM rather than all values and the lack of a standardized protocol for ECMO across all sites. Our definitions of hyperoxia and hypocapnia were based on dichotomized values described in other studies (7, 26, 27) and do not account for the degree or duration of hyperoxia or hypocapnia. Thus, exact levels of PaO2 and PaCO2 or the duration of exposure associated with harm cannot be determined. Three patients had no blood gas values collected in the first 48 hours of ECMO; whether clinicians did not obtain blood gases or whether the research coordinators missed recording their values is unknown. Although many variables were evaluated, potential unmeasured confounders exist. Importantly, this is an observational study and the associations observed do not infer causation. For example, neurologic complications during ECMO are multifactorial, and not entirely caused by blood gas derangements.

CONCLUSIONS

Hyperoxia is common during pediatric ECMO and associated with mortality. Hypocapnia occurs less often and is associated with complications but not mortality. Judicious use of oxygen and avoidance of hyperoxia and hypocapnia may be indicated.

Supplementary Material

Description: This is a table demonstrating duration of ECMO and ICU stay for survivors and non-survivors in the hyperoxia and non-hyperoxia groups.

Description: This is a table of univariable associations between patient factors (i.e., pre-ECMO characteristics and blood gas variables in the first 48 hours of ECMO) and in-hospital mortality.

Description: This is a table of multivariable logistic regression models generated with the best penalized fit in terms of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Only models that included the primary variables of interest, highest PaO2 and lowest PaCO2 in the first 48 hours of ECMO, were considered. The two models shown are regarded as statistically equivalent in terms of penalized fit.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the following research coordinators and data coordinating center staff: Stephanie Bisping, BSN, RN, CCRP, Alecia Peterson, BS and Jeri Burr, MS, RN-BC, CCRC from University of Utah; Mary Ann DiLiberto, BS, RN, CCRC and Carol Ann Twelves, BS, RN from The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Jean Reardon, MA, BSN, RN and Elyse Tomanio, BSN, RN from Children’s National Medical Center; Aimee Labell, MS, RN from Phoenix Children’s Hospital; Margaret Villa, RN and Jeni Kwok, JD from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles; Mary Ann Nyc, BS from UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital; Ann Pawluszka, BSN, RN and Melanie Lulic, BS from Children’s Hospital of Michigan; Monica S. Weber, RN, BSN, CCRP and Lauren Conlin, BSN, RN, CCRP from University of Michigan; Alan C. Abraham, BA, CCRC from University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; and Tammara Jenkins, MSN, RN from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: This work was supported by the following cooperative agreements from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services: U10HD050096, U10HD049981, U10HD049983, U10HD050012, U10HD063108, U10HD063106, U10HD063114, and U01HD049934. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Copyright form disclosure: All authors received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Drs. Reeder, Berg, Shanley, Newth, Pollack, and Carcillo’s institutions received funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Drs. Dalton, Wessel, Harrison, Dean, and Meert’s institutions received funding from the NIH. Dr. Dalton received funding from Maquet and Innovative ECMO Concepts, and she disclosed off-label product use of ECMO. Dr. Shanley received funding from Springer Publishing, International Pediatric Research Foundation (travel support for biannual meeting), and Raynes McCarty Law Firm. Dr. Newth received funding from Philips Research North America and Covidien. Dr. Tamburro received funding from Springer Publishing; he disclosed government work; and he disclosed that receiving grant support from the US FDA Office of Orphan Product Development to study the use of exogenous surfactant in acute lung injury among pediatric hematopoietic cell patients; Ony, Inc. provided the medication free of charge for that trial.

References

- 1.Kilgannon JH, Jones AE, Shapiro NI, et al. Association between arterial hyperoxia following resuscitation from cardiac arrest and in-hospital mortality. JAMA. 2010;303:2165–2171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilgannon JH, Jones AE, Parrillo JE, et al. Relationship between supranormal oxygen tension and outcome after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2011;123:2717–2722. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.001016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson LP, Durward A, Tibby SM. Relationship between arterial partial oxygen pressure after resuscitation from cardiac arrest and mortality in children. Circulation. 2012;126:335–342. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.085100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis DP, Meade W, Sise MJ, et al. Both hypoxemia and extreme hyperoxemia may be detrimental in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrama. 2009;26:2217–2223. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner M, Stein D, Hu P, et al. Association between early hyperoxia and worse outcomes after traumatic brain injury. Arch Surg. 2012;147:1042–1046. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2012.1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klinger G, Beyene J, Shah P, et al. Do hyperoxaemia and hypocapnia add to the risk of brain injury after intrapartum asphyxia? Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F49–52. doi: 10.1136/adc.2003.048785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes RA, Shekar K, Fraser JF. Is hyperoxaemia helping or hurting patients during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation? Review of a complex problem Perfusion. 2013;28:184–193. doi: 10.1177/0267659112473172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald CI, Fraser JF, Coombes JS, et al. Oxidative stress during extracorporeal circulation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;46:937–943. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmerhorst HJF, Roos-Blom MJ, van Westerloo DJ, et al. Associations of arterial carbon dioxide and arterial oxygen concentrations with hospital mortality after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Critical Care. 2015;19:348. doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-1067-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts BW, Kilgannon JH, Chansky ME, et al. Association between postresuscitation partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide and neurological outcome in patients with post-cardiac arrest syndrome. Circulation. 2013;127:2107–2113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider AG, Eastwood GM, Bellomo R, et al. Arterial carbon dioxide tension and outcome in patients admitted to the intensive care unit after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:927–934. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Del Castillo J, Lopez-Herce J, Matamoros M, et al. Hyperoxia, hypocapnia and hypercarbia as outcome factors after cardiac arrest in children. Resuscitation. 2012;83:1456–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramaiah VK, Sharma D, Ma L, et al. Admission oxygenation and ventilation parameters associated with discharge survival in severe pediatric traumatic brain injury. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29:629–634. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1984-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner KJ, Cuschieri J, Copass MK, et al. The impact of prehospital ventilation on outcome after severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2007;62:1330–1336. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804a8032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solaiman O, Singh JM. Hypocapnia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: incidence and association with poor clinical outcomes. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2013;25:254–261. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e3182806465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pappas A, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, et al. Hypocarbia and adverse outcome in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Pediatr. 2011;158:752–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts BW, Karagiannis P, Coletta M, et al. Effects of PaCO2 derangements on clinical outcomes after cerebral injury: A systematic review. Resuscitation. 2015;91:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sznycer-Taub N, Lowery R, Yu S, et al. Hyperoxia is associated with poor outcomes in pediatric patients supported on venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:350–358. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spoelstra-de Man AM, Smit B, et al. Cardiovascular effects of hyperoxia during and after cardiac surgery. Anaesthesia. 2015;70:1307–1319. doi: 10.1111/anae.13218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quarti A, Nardone S, Manfrini F, et al. Effect of the adjunct of carbon dioxide during cardiopulmonary bypass on cerebral oxygenation. Perfusion. 2012;28:152–155. doi: 10.1177/0267659112464382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caputo M, Mokhtari A, Rogers CA, et al. The effects of normoxic versus hyperoxic cardiopulmonary bypass on oxidative stress and inflammatory response in cyanotic pediatric patients undergoing open cardiac surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalton HJ, Reeder R, Garcia-Filion P, et al. Factors associated with bleeding and thrombosis in children receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:762–771. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201609-1945OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaies MG, Gurney JG, Yen AH, et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in infants after cardiopulmonary bypass. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2010;11:234–238. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181b806fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaies MG, Jeffries HE, Niebler RA, et al. Vasoactive-inotropic score is associated with outcome after infant cardiac surgery: An analysis from the Pediatric Cardiac Critical Care Consortium and Virtual PICU System Registries. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15:529–537. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ortiz RM, Cilley RE, Bartlett RH. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in pediatric respiratory failure. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1987;34:39–46. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennet KS, Clark AE, Meert KL, et al. Early oxygenation and ventilation measurements after pediatric cardiac arrest: Lack of association with outcome. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1534–1542. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318287f54c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerra-Wallace MM, Casey FL, Bell MJ, et al. Hyperoxia and hypoxia in children resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Pediatr Crit care Med. 2013;14:e143–e148. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182720440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pollack MM, Holubkov R, Glass P, et al. Functional Status Scale: New pediatric outcome measure. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e18–e28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furnival GM, Wilson RW. Regressions by leaps and bounds. [Accessed June 17, 2017];Technometrics. 1974 16:499–511. Available at JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1267601. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munshi L, Kiss A, Cypel M, et al. Oxygen thresholds and mortality during extracorporeal life support in adult patients. Crit Care Med. 2017 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002643. doi:0.1097/CCM.0000000000002643. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barbaro RP, Paden ML, Guner YS, et al. Pediatric Extracorporeal Life Support Organization Registry International Report 2016. ASAIO Journal. 2017;63:456–464. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Short BL, Walker LK, Bender KS, et al. Impairment of cerebral autoregulation during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in newborn lambs. Pediatr Res. 1993;33:289–294. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199303000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Brien NF, Hall MW. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and cerebral blood flow velocity in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:e126–e134. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182712d62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bembea MM, Lee R, Masten D, et al. Magnitude of arterial carbon dioxide change at initiation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support is associated with survival. J Extra Corpor Technol. 2013;45:26–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peralta C, Jimenez-Castro MB, Gracia-Sancho J. Hepatic ischemia and reperfusion injury: Effects on the liver sinusoidal milieu. J Hepatol. 2013;59:1094–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aufderheide TP, Lurie KG. Death by hyperventilation: A common and life threatening problem during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:S345–351. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000134335.46859.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howard TS, Kalish BT, Wigmore D, et al. Association of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support adequacy and residual lesions on outcomes in neonates supported after cardiac surgery. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17:1045–1054. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description: This is a table demonstrating duration of ECMO and ICU stay for survivors and non-survivors in the hyperoxia and non-hyperoxia groups.

Description: This is a table of univariable associations between patient factors (i.e., pre-ECMO characteristics and blood gas variables in the first 48 hours of ECMO) and in-hospital mortality.

Description: This is a table of multivariable logistic regression models generated with the best penalized fit in terms of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Only models that included the primary variables of interest, highest PaO2 and lowest PaCO2 in the first 48 hours of ECMO, were considered. The two models shown are regarded as statistically equivalent in terms of penalized fit.