Abstract

Rationale

Mitochondrial dysfunction plays an important role in heart failure (HF). However, the molecular mechanisms regulating mitochondrial functions via selective mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) are poorly understood.

Objective

We sought to determine the role of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in selective mitophagy during HF.

Methods and Results

An isoform shift from AMPKα2 to AMPKα1 was observed in failing-heart samples from HF patients and transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced mice, accompanied by decreased mitophagy and mitochondrial function. The recombinant adeno-associated virus Serotype 9-mediated overexpression of AMPKα2 in mouse hearts prevented the development of TAC-induced chronic HF by increasing mitophagy and improving mitochondrial function. In contrast, AMPKα2−/− mutant mice exhibited an exacerbation of the early progression of TAC-induced HF via decreases in cardiac mitophagy. In isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes (CMs), AMPKα2 overexpression mechanistically rescued the impairment of mitophagy after phenylephedrine (PE) stimulation for 24 h. Genetic knockdown of AMPKα2, but not AMPKα1, by short interfering RNA suppressed the early phase (6 h) of PE-induced compensatory increases in mitophagy. Furthermore, AMPKα2 specifically interacted with phosphorylated PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) at Ser495 after PE stimulation. Subsequently, phosphorylated PINK1 recruited the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Parkin, to depolarized mitochondria, and then enhanced the role of the PINK1-Parkin-sequestosome-1 pathway involved in cardiac mitophagy. This increase in cardiac mitophagy was accompanied by the elimination of damaged mitochondria, improvement in mitochondrial function, decrease in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and apoptosis of CMs. Finally, Ala mutation of PINK1 at Ser495 partially suppressed AMPKα2 overexpression-induced mitophagy and improvement of mitochondrial function in PE-stimulated CMs, whereas Asp (phosphorylation-mimic) mutation promoted mitophagy after PE stimulation.

Conclusions

In failing hearts, the dominant AMPKα isoform switched from AMPKα2 to AMPKα1, which accelerated HF. The results show that phosphorylation of Ser495 in PINK1 by AMPKα2 was essential for efficient mitophagy to prevent the progression of HF.

Keywords: AMPKα2, PINK1, heart failure, mitophagy, mitochondria

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure (HF) is the most common cardiovascular disorder in clinical practice1. This disorder causes impaired cardiac function and markedly increases hospitalization and mortality risk2. In a normal heart, cardiac mitochondria produce vast amounts of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by oxidative phosphorylation to maintain the contractile function of cardiac muscle. However, cardiac mitochondria are also the primary source of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction, cardiomyocyte (CM) damage, and HF. To protect against mitochondrial damage, CMs develop well-coordinated quality control mechanisms that maintain overall mitochondrial health through mitochondrial biogenesis, mitochondrial dynamics, and mitophagy. Any impairment of these processes can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death3, 4.

Mitophagy is a specific class of autophagy that cleans out dysfunctional mitochondria in the heart under normal physiological conditions, as well as in response to pathological stresses. Although accumulating evidence suggests that dysregulation of mitophagy can induce CM death and HF5–7, the basic regulation mechanisms underlying organelle-specific mitophagy during pathological HF have not been well elucidated.

Currently, most studies have demonstrated that the mechanism of mitophagy in CMs is mediated by the cytosolic E3 ubiquitin ligase, Parkin8, and the mitochondrial membrane kinase, PTEN-induced putative kinase-1 (PINK1)9. PINK1 is selectively stabilized in mitochondria with diminished electrochemical potentials across their inner membranes and recruits Parkin to the mitochondria to activate its E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. The Parkin-mediated ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins is the signal for engulfment of the organelle by autophagosomes and subsequent transfer to degradative lysosomes; thereafter, the components are either recycled or eliminated. Previous studies have revealed that the stabilization of PINK1 on the depolarized mitochondrial membrane recruits Parkin to the mitochondria by phosphorylating mitofusin 2 (MFN2)10; this process is accelerated after the autophosphorylation of PINK111. The damaged mitochondria are sensed by the decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and transduced to Parkin via the autophosphorylation of PINK1, thus highlighting the importance of PINK1 in regulating the PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy pathway.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a cellular energy sensor and a metabolic master switch that plays a pivotal role in cell growth and survival, as well as in whole-body energy homeostasis12, 13. AMPK is a heterotrimeric complex composed of a catalytic α-subunit and two regulatory β- and γ-subunits. Each subunit exists in multiple isoforms encoded by separate genes (α1, α2, β1, β2, γ1, γ2, and γ3). AMPK is activated in response to stresses that deplete intracellular ATP, leading to a rise in the AMP/ATP ratio. Increased AMPK activity leads to the phosphorylation of an array of protein targets, resulting in enhanced ATP production and/or reduced energy expenditure14, 15. AMPK activity is markedly increased during cardiac stresses such as ischemia16 and pathological cardiac hypertrophy17, 18, and the failure to activate AMPK under these conditions is associated with a poor outcome. Furthermore, AMPK-mediated general autophagy is essential for the ischemic response in the heart16. A recent study has shown that AMPK mediates mitochondrial fission in response to energy stress19. However, whether AMPK is involved in selective mitophagy or the maintenance of mitochondrial function via mitophagy during HF is currently unknown.

In this study, we used heart samples from HF patients and AMPKα2 genetically modified mouse models with transverse aortic constriction (TAC) to investigate the role of AMPKα2-mediated selective mitophagy during HF. We identified a serine residue (Ser495) in PINK1 that underwent phosphorylation after exposure to AMPKα2 upon dissipation of the ΔΨm in CMs. Our results show that this phosphorylation event was important for the efficient retrieval of Parkin to the mitochondria in order to increase the rate of mitophagy during HF.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article [and its online supplementary files].

Human heart samples

Samples from explanted hearts used in this study were obtained from five HF patients who had received heart transplants and six age-matched donors (clinical characteristics of patients are listed in Online Table I) at Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology. All study participants provided informed written consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The following topics and experiments are described in the Online Data Supplement: reagents, recombinant AAV9-cTNT-mediated gene transfer, TAC surgery in WT and AMPKα2−/− mice, histological analysis, confocal immunofluorescence microscopy, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), mitochondrial isolation, mitochondrial respiration studies, CM culture and treatment, ROS measurements, AMPK activity assay, autophagy detection using the mRFP-GFP adenoviral vector, phos-tag assay, flow cytometry, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of PINK1-myc, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for the purification of non-myocyte fractions, co-immunoprecipitation, and immunoblotting.

RESULTS

Mitochondrial dysfunction in HF is associated with a switch in AMPKα isoforms in the heart

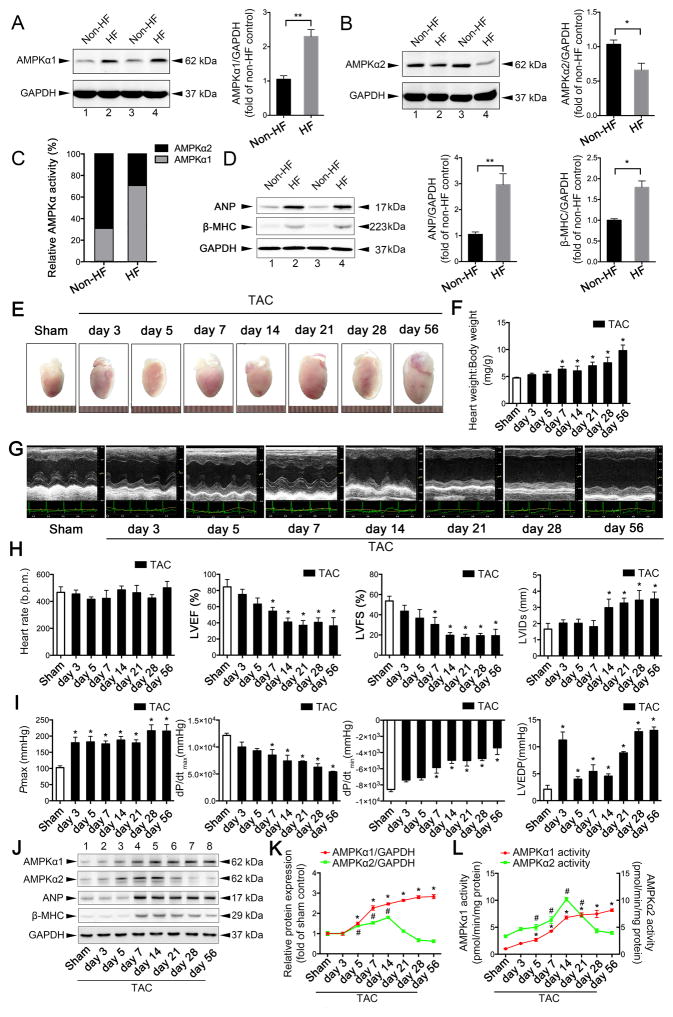

Emerging evidence points to the disruption of energy homeostasis and mitochondrial dysfunction as major causes of cardiac hypertrophy and progression to HF20, 21. Using heart tissue samples from HF patients and healthy donors, we analyzed the mitochondrial abnormalities that occurred during HF, including irregular mitochondrial arrangement, swelling, reduced density, and rates of mitophagy (Online Figure I A–B). ROS production was higher in HF tissues than in normal heart tissues (Online Figure I A–B). However, mitochondrial complex I–IV protein contents (Online Figure I C–D), mitochondrial DNA levels (Online Figure I E), ATP production (Online Figure I F), and mitochondrial complex I–IV activity (Online Figure I G–J) were all decreased in failing-heart tissues, suggesting that mitochondrial dysfunction occurs in HF patients. Given the importance of AMPK in energy metabolism, we further examined the relationship between AMPK and mitochondrial dysfunction. Immunoblots showed an increase in the expression of AMPKα1 in the tissues of HF patients, but the expression of AMPKα2 decreased (Figure 1A–B, Online Figure II A–C); these changes were accompanied by increases in the expression of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and beta-myosin heavy chain (β-MHC) (Figure 1D). An AMPKα activity assay revealed that the ratio of AMPKα2:AMPKα1 activity decreased to 30%:70% in failing hearts, whereas the ratio in healthy hearts was approximately 70%:30%22 (Figure 1C); this suggests that an AMPKα isoform switch occurs during the progression of HF. Additionally, the general cardiac autophagy level was decreased in failing hearts (Online Figure II D–G).

Figure 1. Mitochondrial dysfunction in heart failure (HF) is associated with a switch in AMPKα isoforms.

A. Protein extracts of myocardial samples from control (non-HF) hearts (n = 6) and hearts from patients with severe HF (n = 5) were normalized to equal protein levels (GAPDH: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase). Representative immunoblots of AMPKα1 expression and quantitative analysis are shown. **P < 0.01 vs. non-HF patients. B. Representative immunoblots of AMPKα2 expression and quantitative analysis. *P < 0.05 vs. non-HF patients. C. Relative AMPKα activities are shown. D. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and β-myosin heavy chain (MHC) were upregulated in the failing human heart; *P < 0.05 vs. non-HF patients; **P < 0.01 vs. non-HF patients. E. C57BL/6J mice were subjected to either sham operation (n = 20) or transverse aortic constriction (TAC) and observed after 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 28, or 56 days (n = 9, 10, 12, 10, 9, 11, or 12, respectively). Gross morphologies of adult hearts in wild-type (WT) mice after TAC at different days are shown. F. Heart weight:body weight ratios of adult WT mice after TAC. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group. G. Representative images of echocardiograms. H. Heart rate, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), fractional shortening (LVFS), and left ventricular internal diameter at end-systole (LVIDs) are presented. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group. I. Peak systolic pressure (Pmax), peak instantaneous rate of left ventricular pressure increase (dP/dtmax), peak instantaneous rate of decline in left ventricular pressure increase (dP/dtmin), and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) were detected by the Millar catheter system in mouse hearts after TAC. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group. J. Representative immunoblots show expression levels of AMPKα1, AMPKα2, ANP, and β-MHC in mouse hearts after TAC. K. Expression levels of AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 were quantified and shown as relative protein expression after normalization to GAPDH. For AMPKα1: *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; For AMPKα2: #P < 0.05 vs. sham group. L. AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 activities were measured by detecting their substrate, SAMS peptide. For AMPKα1: *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; For AMPKα2: #P < 0.05 vs. sham group. All data represent mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

To further confirm whether mitochondrial dysfunction was associated with alterations in the activity of AMPKα isoforms in failing hearts, WT C57BL/6J mice were subjected to TAC and observed at multiple time points over 56 days. TAC surgery considerably increased blood velocity in the aortic arch of both WT and AMPKα2−/− mice (Online Figure III A–B). In addition, the pressures in the aortic arch did not differ after 5 or 28 days, suggesting that TAC surgery was successful. Cardiac hypertrophy developed after 7 days, as shown by an increase in heart weight:body weight ratio (Figure 1E–F) and left ventricular posterior wall (LVPW) thickness (Figure 1G, Online Figure III F–G). A reduction in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS) was seen 7 days after TAC, and HF was observed after 28 days (Figure 1H). The Millar catheter depicted similar changes through echocardiographic analysis. Decreases in dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin were observed 7 days after TAC (Figure 1I). The Pmax and left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) were increased 3 days after TAC (Figure 1I). Interestingly, the expression levels of AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 showed an initial increase 5 days after TAC, but the expression of AMPKα2 began to decrease 14 days after TAC. Similarly, AMPKα1 and AMPKα2 activity showed an initial increase 5 days after TAC, but AMPKα2 activity showed a considerable decrease 14 days after TAC. This decrease in AMPKα2 activity was negatively associated with the expressions of ANP and β-MHC, which are markers of HF (Figure 1J–L).

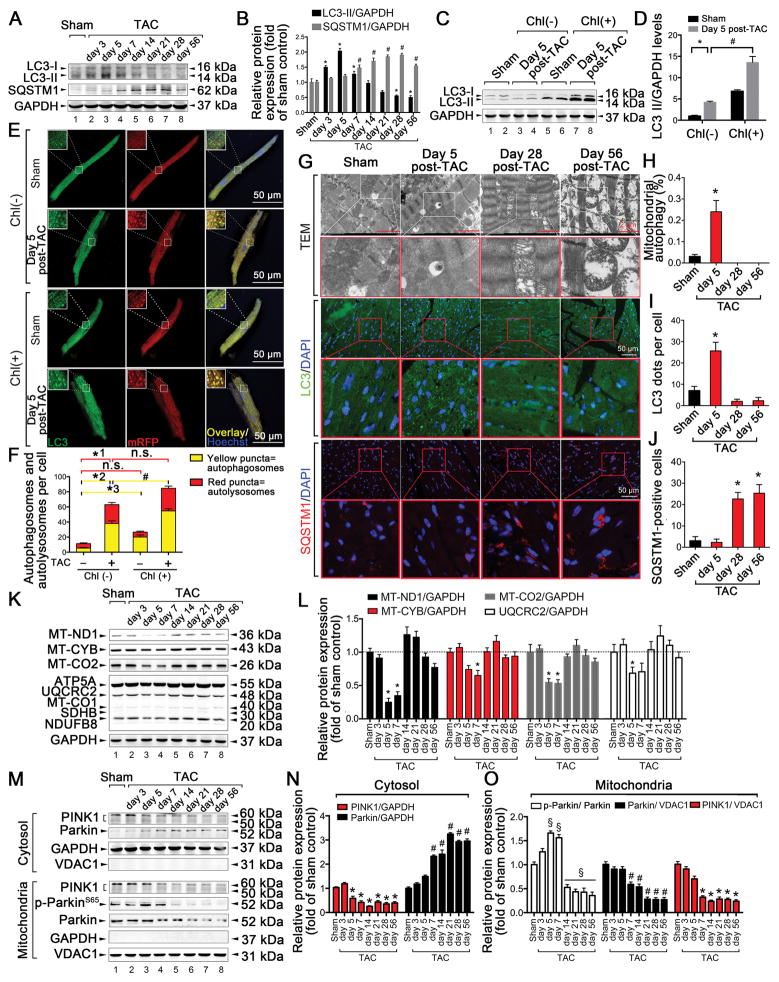

General autophagy and mitophagy are transiently increased in cardiac tissues during the early phase of HF but are downregulated during the chronic phase of TAC-induced HF

Previous studies have shown that AMPKα contributes to the initiation of general autophagy23. During HF, the role of AMPKα2 in the activation of mitophagy is not well understood. Therefore, we first examined general autophagy in the cardiac tissue of TAC-induced mice based on the levels of light chain 3 (LC3) and sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1). LC3-II levels were increased at 3, 5, and 7 days after TAC, returned to basal levels at 14 days, and showed a considerable decrease after 28 days. Moreover, in the presence of the autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (chl), LC3-II levels showed a greater increase 5 days after TAC (Figure 2A–D). SQSTM1 showed an increase from 7 days after TAC (Figure 2A–B). Next, autophagic flux was evaluated in primary adult mouse CMs transduced with Ad-mRFP-GFP-LC324. Both GFP/RFP double-positive autophagosomes (yellow) and RFP-positive autolysosomes (red) showed a considerable increase at 5 days in the TAC group compared to the sham group. Furthermore, chl induced a considerably greater increase in the number of yellow dots at day 5 in the TAC group compared to the sham group (Figure 2E–F). These results suggest that autophagic flux is increased in the early phase of TAC (5 days). In addition to general autophagy, we examined the extent of mitophagy by TEM in TAC-induced mice. The incorporation of mitochondria into autophagic vacuoles was found more frequently in the hearts of TAC-induced mice than in the hearts of sham mice at day 5 post-surgery, accompanied with increased LC3-II levels and decreased SQSTM1 levels (Figure 2G–J); this is indicative of an increase in mitophagy after 5 days. Conversely, during the chronic phase (28 days and 56 days) of TAC, mitophagy levels showed a considerable decrease, along with increased incidences of irregular mitochondrial arrangement, swelling, and reduced density (Figure 2G–H). Several mitochondrial protein complex subunits (MT-ND1, MT-CYB, MT-CO2, and UQCRC2) showed a transient decrease during the early phase of TAC (5 and 7 days), but these levels returned to baseline during the chronic phase (Figure 2K–L). This suggests a compensatory increase in mitophagy during the early phase of TAC, as well as suppression of mitophagy during the chronic phase of TAC. Additionally, the protein most commonly associated with mitophagy, PINK1, showed a gradual decrease in both the cytosol and mitochondria during the initial 5 days after TAC. During the same period, the translocation of Parkin from the cytosol to the mitochondria was attenuated in the hearts of TAC-induced mice (Figure 2M–O). Activities of PINK1, as reflected by p-Parkin S6525, were initially increased at 5 and 7 days after TAC and were rapidly reduced 14 days after TAC (Figure 2M, 2O). These data suggest that cardiac mitophagy is transiently increased during the early phase but is downregulated during the chronic phase of TAC-induced HF. Furthermore, this was associated with changes in the expression levels and activities of PINK1.

Figure 2. Cardiac general autophagy and mitophagy are transiently increased during the early phase of TAC-induced HF but are downregulated during the chronic phase.

C57BL/6J mice were subjected to either sham operation (n = 20) or TAC and observed after 3, 5, 7, 14, 21, 28, or 56 days (n = 9, 10, 12, 10, 9, 11, or 12, respectively). A–B. Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of whole-cell heart homogenates for light chain 3 (LC3) and sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1) are shown. For LC3-II: *P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated mice. For SQSTM1: #P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated mice. C–D. Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of whole-cell heart homogenates for LC3 and GAPDH in the presence of chloroquine (chl). E. C57BL/6J mice were subjected to either sham operation (n = 8) or 5 days post-TAC (n = 6) in the presence or absence of intraperitoneally injected chl (10 mg/kg). Representative confocal images of mRFP-GFP-LC3 puncta in primary isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes (CMs) are shown. Scale bar, 50 μm. F. Bar graph shows the mean number of autophagosomes (yellow dots) and autolysosomes (red dots) per cell. *1P < 0.05, *2P < 0.05, *3P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated mice; #P < 0.05 vs. 5-day TAC-operated mice without chl. G. Representative images from transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and showing fluorescence staining of LC3 and SQSTM1 after sham operation (n = 5) or TAC for 5, 28, or 56 days (n = 5, 6, or 5, respectively). H. Bar graphs indicate the number of autophagosomes containing mitochondria per total number of mitochondria from a cross-sectional assessment of the heart tissues in TEM. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group. I. Autophagy was quantified by counting the green LC3 puncta in CMs. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group. J. Number of SQSTM1-positive CMs is shown. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group. K-L. Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of MT-ND1, MT-CYB, MT-CO2, and electron transport chain (ETC) complexes in whole-cell heart homogenates. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group. M. Top, representative immunoblots of PINK1 and Parkin in the cytosolic fraction prepared from heart homogenates; Bottom, representative immunoblots of PINK1, p-Parkin S65, and Parkin in the mitochondrial fraction prepared from heart homogenates. N. Quantitative analysis of PINK1 and Parkin in the cytosolic fraction. For PINK1: *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; For Parkin: #P < 0.05 vs. sham group. O. Quantitative analysis of p-Parkin S65/Parkin, PINK1, and Parkin in the mitochondrial fraction. For PINK1: *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; For Parkin: #P < 0.05 vs. sham group. §P < 0.05 vs. sham group. All data represent the mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

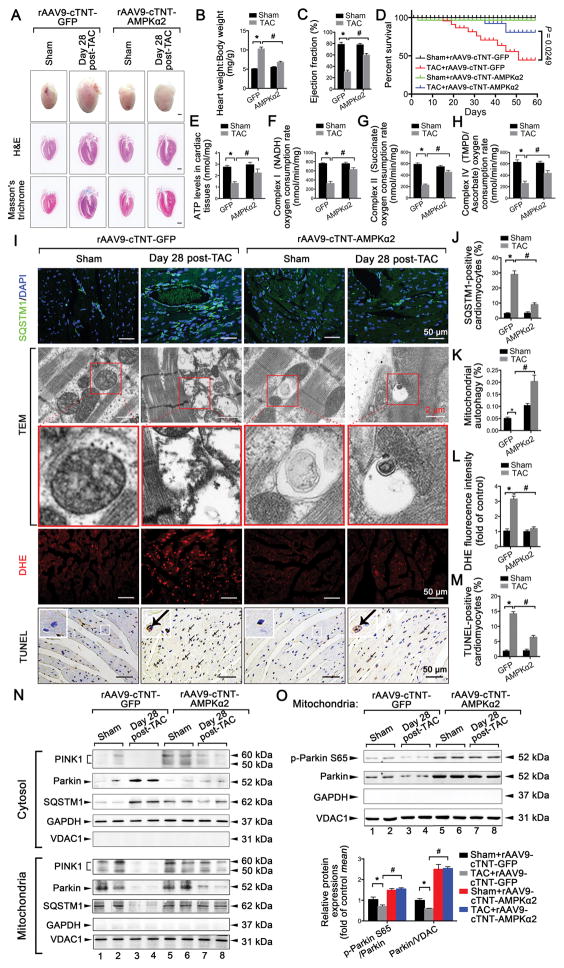

AMPKα2 protects mice against TAC-induced HF by increasing cardiac mitophagy associated with PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway activation

To confirm whether the reduced activity of AMPKα2 exacerbated HF via the downregulation of cardiac mitophagy, we examined the extent of mitophagy in mice after TAC through AMPKα2 gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments. The rAAV9-cTNT-mediated overexpression of AMPKα2 protected heart tissues against chronic TAC-induced HF in mice; this was indicated by reduced heart weight:body weight ratios (Figure 3A–B), attenuated lung edema (Online Figure IV A), and increased LVEF (Figure 3C) and LVFS values (Online Figure IV B–C). The area of CMs with fibrosis also showed a greater decrease after AMPKα2 overexpression compared with TAC at 28 days (Online Figure IV F–G). Protein and mRNA levels of HF markers (ANP and β-MHC; Online Figure IV D–E) and the survival rate (Figure 3D) were lower after cardiac AMPKα2 overexpression (Online Figure V A–C) compared with TAC at 28 days. Furthermore, mitochondrial function was elevated to higher levels after cardiac AMPKα2 overexpression compared with TAC at 28 days; this included recovered ATP synthesis (Figure 3E) and enhanced mitochondrial complex activity (Figure 3F–H). Cardiac overexpression of AMPKα2 suppressed the accumulation of SQSTM1 in cardiac tissues compared with TAC at 28 days (Figure 3I–J). TEM revealed that the incorporation of mitochondria into autophagic vacuoles was not found in the hearts of TAC-induced mice at day 28, but the overexpression of AMPKα2 rescued mitophagy rates (Figure 3I and 3K). ROS production (Figure 3I and 3L) and CM apoptosis (Figure 3I and 3M) were reduced after AMPKα2 overexpression. In addition, PINK1 was increased in the mitochondrial fraction after AMPKα2 overexpression. Parkin translocation from the cytosol to the mitochondria, as well as the subsequent recruitment of SQSTM1, were enhanced in the hearts of TAC-induced mice after AMPKα2 overexpression (Figure 3N). Activities of PINK1, as reflected by p-Parkin S65, were also increased in the hearts of TAC-induced mice after AMPKα2 overexpression (Figure 3O). These results suggest that the cardiac overexpression of AMPKα2 protects mice against chronic TAC-induced HF by increasing cardiac mitophagy and rescuing mitochondrial function. This role of AMPKα2 was partially mediated by the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 mitophagy pathway.

Figure 3. Overexpression of AMPKα2 protects mice against TAC-induced HF associated with increasing cardiac mitophagy.

C57BL/6J mice were first injected with rAAV9-cTNT-AMPKα2 in the caudal vein; rAAV9-cTNT-GFP was used as a control. After 2 weeks, infected mice were subjected to either sham operation (n = 20 in rAAV9-cTNT-AMPKα2 group; n = 20 in rAAV9-cTNT-GFP group) or TAC for 28 days (n = 25 in rAAV9-cTNT-AMPKα2 group; n = 25 in rAAV9-cTNT-GFP group). A. Gross morphology by Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome staining of adult hearts from WT C57BL/6J mice. Scale bars, 1.0 mm. B. Heart weight:body weight ratios of adult WT mice. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in the green fluorescent protein (GFP) group. C. Ejection fraction is shown. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in GFP group. D. Survival curve of mice in sham+rAAV9-cTNT-GFP, TAC+rAAV9-cTNT-GFP, sham+rAAV9-cTNT-AMPKα2, and TAC+ rAAV9-cTNT-AMPKα2 groups (n = 15, 20, 16, or 22, respectively) (P = 0.0249, log-rank test). E. Myocardial ATP levels. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in GFP group. F–H. Oxygen consumption by each mitochondrial complex was calculated (n = 5–7 per group). *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in GFP group. I. Representative images of SQSTM1 staining, TEM, dihydroethidium (DHE) staining, and the TUNEL assay in mouse heart tissues after sham operation (n = 8) or 28 days after TAC (n = 9). J. Number of SQSTM1-positive CMs. K. Bar graphs indicate the number of autophagosomes containing mitochondria per total number of mitochondria from a cross-sectional assessment of the heart tissues in TEM. L. Myocardial reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels. M. Quantitative analysis of TUNEL-positive CMs. N. Top, representative immunoblots of PINK1, Parkin, and SQSTM1 in the cytosolic fraction prepared from heart homogenates; Bottom, representative immunoblots of PINK1, Parkin, and SQSTM1 in the mitochondrial fraction prepared from heart homogenates (n = 4 for each group). O. Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of p-Parkin S65 and Parkin in the mitochondrial fraction prepared from heart homogenates (n = 4 for each group) are shown. All data represent the mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

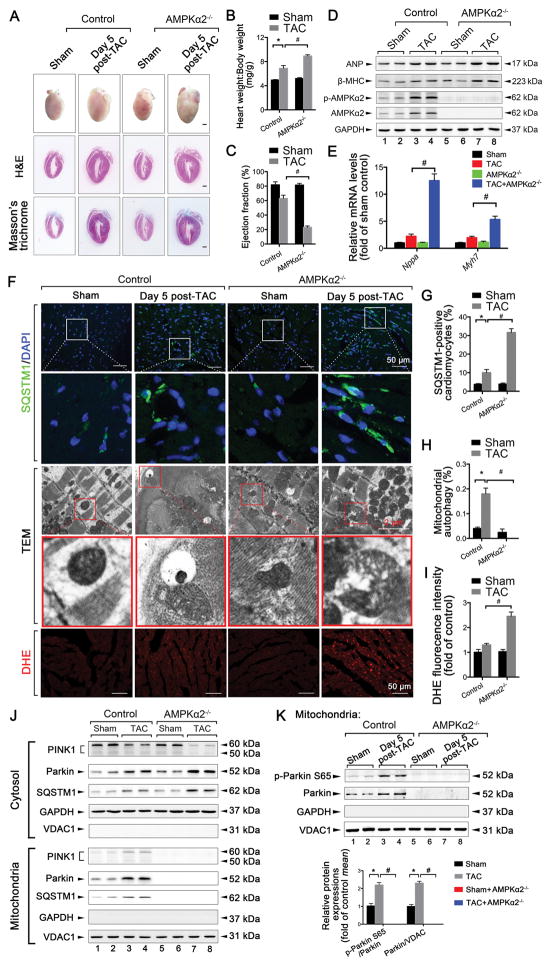

In contrast, the deletion of AMPKα2 exacerbated early TAC-induced HF in mice; this was reflected by increases in heart weight:body weight ratios, increases in lung edema, and decreases in LVEF and LVFS values (Figure 4A–C and Online Figure IV I–K). ANP and β-MHC showed a greater increase in AMPKα2−/− mice than in TAC-induced mice at 5 days (Figure 4D–E). The area of CMs with cardiac fibrosis also showed a greater increase in AMPKα2−/− mice compared with TAC-induced mice at 5 days (Online Figure IV L–N). Additionally, SQSTM1 accumulation was increased in cardiac tissues compared with TAC at 5 days (Figure 4F–G). TEM revealed a transient increase in the incorporation of mitochondria into autophagic vacuoles 5 days after TAC; this was not found in the hearts of TAC-induced AMPKα2−/− mice (Figure 4F and H). ROS production showed a greater increase in AMPKα2−/− mice compared with TAC-induced mice at 5 days (Figure 4F and I). Levels of mitochondrial PINK1 and Parkin were not observed in AMPKα2−/− mice (Figure 4J), and no activities of PINK1 were detected in the hearts of TAC-induced mice after AMPKα2−/− (Figure 4K). These results confirm that the deletion of AMPKα2 accelerated the progression of early TAC-induced HF by reducing cardiac mitophagy levels and mitochondrial function. The PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway was also impaired in AMPKα2−/− mice 5 days after TAC (Online Figure VI A and Figure 4J).

Figure 4. Deletion of AMPKα2 exacerbates early TAC (5 days)-induced HF in mice by reducing cardiac mitophagy. AMPKα2−/− mice and control littermates were subjected to either sham operation (n = 10 in the control group, n = 12 in the AMPKα2−/− group) or TAC for 5 days (n = 12 in control group, n = 14 in AMPKα2−/− group).

A. Gross morphology by H&E and Masson’s trichrome staining of adult hearts from WT C57BL/6J mice. Scale bars, 1.0 mm. B. Heart weight:body weight ratios of adult WT mice. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in control group. C. Ejection fraction is shown. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in control group. D. Representative immunoblots of ANP, β-MHC, p-AMPKα2, and AMPKα2 proteins in lysates prepared from heart homogenates (n = 4 for each group). E. RT-qPCR analyses of the relative expression of nppa and myh7 from the hearts of mice exposed to the indicated conditions (n = 4 for each group). F. Representative images of SQSTM1 staining, TEM, and DHE staining in heart sections from mice after sham operation (n = 5) or TAC for 5 days (n = 6). G. Number of SQSTM1-positive CMs. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in control group. H. Bar graphs indicate the number of autophagosomes containing mitochondria per total number of mitochondria from a cross-sectional assessment of the heart tissues in TEM. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in control group. I. Myocardial ROS levels. *P < 0.05 vs. sham group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC in control group. J. Top, representative immunoblots of PINK1, Parkin, and SQSTM1 in the cytosolic fraction prepared from heart homogenates. Bottom, representative immunoblots of PINK1, Parkin, and SQSTM1 in the mitochondrial fraction prepared from heart homogenates (n = 4 for each group). K. Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of p-Parkin S65 and Parkin in the mitochondrial fraction prepared from heart homogenates (n = 4 for each group). All data represent the mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

Moreover, AMPKα2 was able to upregulate mitochondrial biogenesis via PGC-1α (Online Figure VI B–D). Thus, the cardioprotective role of AMPKα2 against HF involved both mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy.

Overexpression of AMPKα2 prevents the PE-induced impairment of mitophagy in CMs

We examined the effects of AMPKα2 on the stimulation of mitophagy in primary isolated adult mouse CMs. CMs were stimulated with PE at different time points to mimic similar alterations in failing hearts in vivo. PE stimulation for 6 h induced the activation of AMPKα2, but no change in ANP expression was observed. PE stimulation over a longer period (24 h) reduced the activation of AMPKα2 and LC3-II and increased the expression of ANP (Online Figure VII A–B). PE stimulation for 6 h and 24 h were used to mimic early and late phase interventions, respectively, in subsequent experiments.

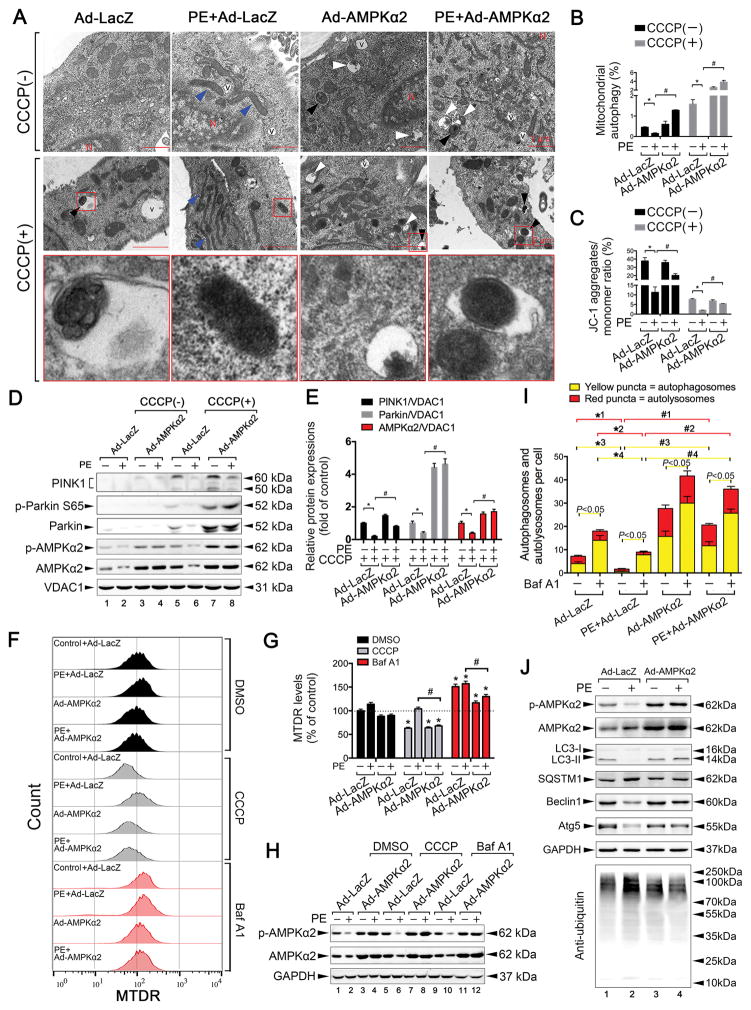

In early PE-induced HL-1 cells, intervention with the short interfering RNA (siRNA) si-AMPKα2, but not si-AMPKα1, inhibited PE-induced compensatory increases in mitophagy (Online Figure VIII A–B). Moreover, 24 h of PE stimulation markedly inhibited mitophagy in CMs in the presence or absence of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins or carbonyl cyanide p-trichloromethoxyphenylhydrazone (CCCP; Figure 5A–B; Online Figure VIII C). Compared to the PE group, more mitochondria were found to be incorporated into autophagic vacuoles after overexpression of AMPKα2; this effect was more pronounced in the presence of CCCP (Figure 5A–B). Furthermore, overexpression of AMPKα2 showed a greater increase in the ΔΨm than 24 h of PE stimulation (Figure 5C, Online Figure VII F). To confirm that mitochondria were degraded by an autophagic process, we measured the colocalization of LC3 with mitochondria after mitochondrial depolarization using CMs infected with adenovirus GFP-LC3. Colocalization of mitotracker-labelled mitochondria and LC3-labelled autophagosomes was not found in PE-stimulated CMs, but colocalization increased in the AMPKα2-overexpressed group after 8 h of CCCP treatment (Online Figure VII C–D). Both expression levels and activities of PINK1 were increased following AMPKα2 overexpression after PE stimulation, and this was more obvious in the presence of CCCP (Figure 5D–E). Examination of the mitochondrial contents by cytometry revealed that PE stimulation induced an accumulation of mitochondria in the presence of CCCP, whereas the overexpression of AMPKα2 markedly reduced the number of damaged mitochondria (Figure 5F–H). Autophagic flux was then evaluated in CMs treated with Ad-mRFP-GFP-LC3. PE stimulation resulted in a decreased number of GFP/RFP double-positive autophagosomes (yellow) and RFP-positive autolysosomes (red). AMPKα2 overexpression prevented the PE-induced inhibition of autophagic flux by increasing the activity of autophagosomes and autolysosomes. Furthermore, the autophagy inhibitor Bafilomycin (Baf) A1 induced a much greater increase in the number of yellow dots in each group than the corresponding group without Baf A1 (Figure 5I and Online Figure VII E). These results suggest that AMPKα2 can increase autophagic flux after PE stimulation. Additionally, in PE-induced CMs, the expression levels of LC3-II, Beclin-1, and autophagy protein 5 increased, but SQSTM1 expression was reduced after the activation of AMPKα2. Overexpression of AMPKα2 also decreased ubiquitin activity in CMs (Figure 5J). Hence, the overexpression of AMPKα2 prevented the PE-induced impairment of mitophagy in CMs.

Figure 5. Overexpression of AMPKα2 prevents the phenylephedrine (PE)-induced impairment of mitophagy in CMs.

A. HL-1 mouse CMs were infected with an adenovirus encoding AMPKα2 and then subjected to PE (50 μmol/L) stimulation, followed by the induction of mitophagy. Mitophagy induction was performed by treatment with 20 μmol/L CCCP 24 h after PE stimulation. Representative images of TEM assay are shown. B. Mitophagy levels in CMs. Bar graph indicates the number of autophagosomes containing mitochondria (black arrows in [A]) per total number of mitochondria from a cross-sectional assessment of the CMs in TEM. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-LacZ group; #P < 0.05 vs. PE+Ad-LacZ group. Blue arrows in (A) indicate prolonged mitochondria. C. Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was examined by flow cytometry with JC-1 probe treatment. The excitation ratio (JC-1 aggregates, red; monomer, green) indicates ΔΨm. Bar graphs indicate the quantification of ΔΨm. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-LacZ group; #P < 0.05 vs. PE+Ad-LacZ group. D. Representative immunoblots of PINK1, p-Parkin S65, and Parkin in the presence or absence of CCCP in HL-1 CMs are shown. E. Quantitative analysis of PINK1/VDAC1, Parkin/VDAC1, and p-AMPKα2/AMPKα2 in the presence of CCCP. F. Isolated mouse adult CMs were infected with an adenovirus encoding AMPKα2 and then subjected to PE (50 μmol/L) stimulation, followed by the induction of mitophagy or treatment with 0.1 μmol/L bafilomycin A1 (Baf A1). Representative contour plots of CMs stained with MitoTracker are shown. G. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of MitoTracker Deep Red. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-LacZ group; #P < 0.05 vs. corresponding PE+Ad-LacZ group. H. Expression levels of p-AMPKα2 and AMPKα2 in (F). I. Bar graph indicates the mean number of autophagosomes (yellow) and autolysosomes (red) per cell. *1P < 0.05, *3P < 0.05 vs. Ad-LacZ group; #1P < 0.05, #3P < 0.05 vs. corresponding PE+Ad-LacZ group; *2P < 0.05, *4P < 0.05 vs. Baf A1+Ad-LacZ group; #2P < 0.05, #4P < 0.05 vs. Baf A1+PE+Ad-LacZ group. Lines in yellow indicate statistical comparisons for autophagosomes; Lines in red indicate statistical comparisons for autolysosomes; J. Representative immunoblots of p-AMPKα2, AMPKα2, LC3, SQSTM1, Beclin1, autophagy protein 5 (Atg5), and anti-ubiquitin in CMs are shown. All data represent the mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

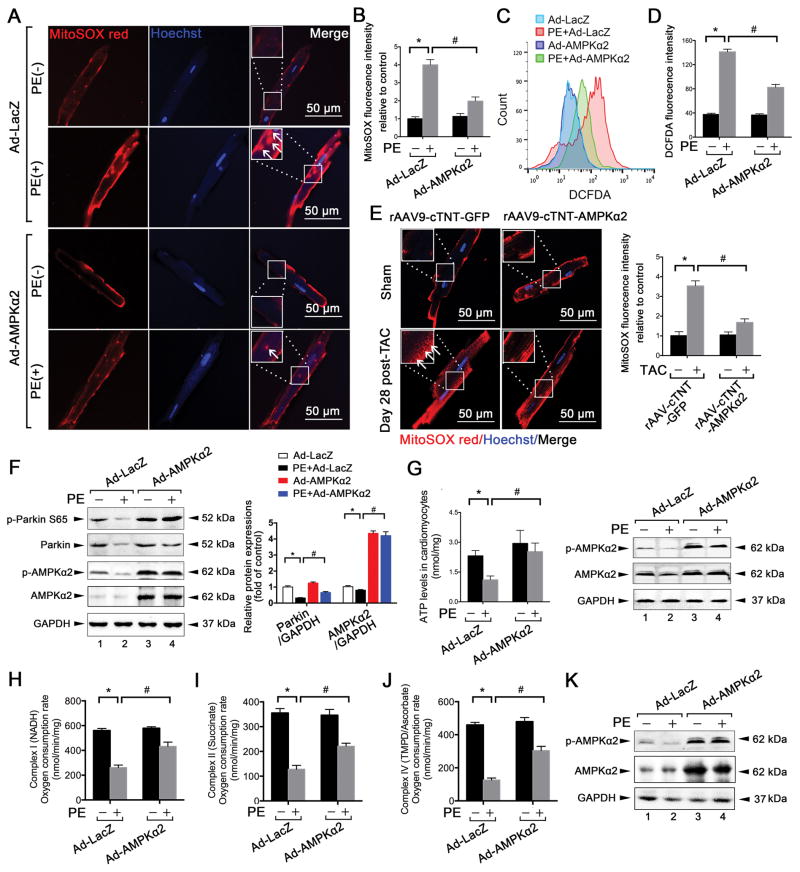

Overexpression of AMPKα2 attenuates PE-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in CMs

Given that AMPKα2 prevented the PE-induced impairment of mitophagy in CMs, we further investigated whether mitochondrial function would recover after overexpression of AMPKα2. MitoSOX red staining revealed that the overexpression of AMPKα2 prevented the late PE-induced elevation of mitochondria-derived ROS production in CMs (Figure 6A–B). Similarly, overexpression of AMPKα2 reduced total ROS levels compared to PE in CMs (Figure 6C–D). Cardiac overexpression of AMPKα2 attenuated mitochondria-derived ROS production in primary adult mouse CMs after TAC for 28 days (Figure 6E). Meanwhile, activities of PINK1 were also increased after AMPKα2 overexpression (Figure 6F). Additionally, ATP production (Figure 6G) and mitochondrial complex (I, II, and IV) activity recovered after AMPKα2 overexpression in PE-induced CMs (Figure 6H–K). These data demonstrate that AMPKα2 attenuated PE-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in CMs following increased levels of mitophagy.

Figure 6. Overexpression of AMPKα2 attenuates PE-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in CMs.

A. Isolated mouse adult CMs were infected with an adenovirus encoding AMPKα2 and then subjected to PE (50 μmol/L) stimulation. Isolated mouse adult CMs from the indicated groups were stained by immunocytochemistry for mitoSOX (red) and nuclei (blue). Scale bar, 50 μm. B. Quantitative analysis of the MFI of mitoSOX. *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-LacZ group; #P < 0.05 vs. PE+Ad-LacZ group. C. ROS levels of CMs from (A) were scored by 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin diacetate-fluorescence-activated cell sorting (DCFDA-FACS). D. MFI values of DCFDA staining in the indicated groups. E. MitoSOX (red) and nuclei (blue) staining for 28-day, TAC-induced CMs after cardiac overexpression of AMPKα2. *P < 0.05 vs. rAAV9-cTNT GFP group; #P < 0.05 vs. TAC+ rAAV9-cTNT-AMPKα2 group. F. Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of p-Parkin S65, Parkin, p-AMPKα2, and AMPKα2 of CMs from (A) are shown. G. ATP levels of CMs from (A). H–K. Oxygen consumption by each mitochondrial complex was calculated in CMs from (A). *P < 0.05 vs. Ad-LacZ group; #P < 0.05 vs. PE+Ad-LacZ group. All data represent the mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

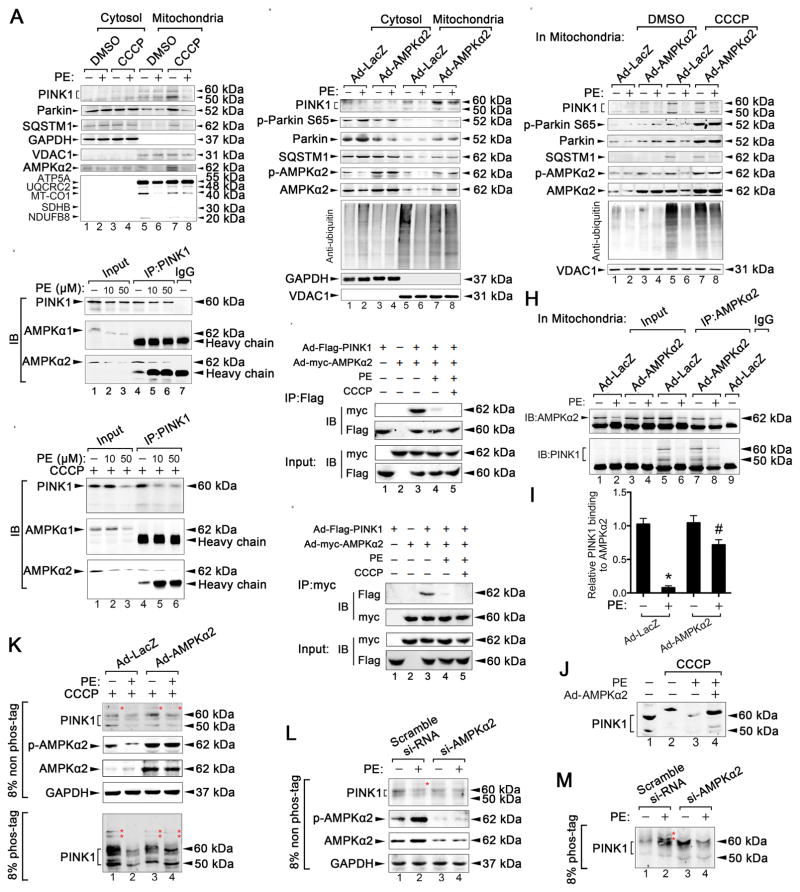

AMPKα2 interacts with PINK1 to enhance the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway

We then investigated whether AMPKα2 also enhanced cardiac mitophagy in PE-induced isolated adult mouse CMs via the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway in vitro. Late PE stimulation substantially inhibited the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway in the presence of CCCP, accompanied with reduced AMPKα2 expression (Figure 7A, lane 8). Upon overexpression of AMPKα2, the roles of the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway were enhanced in the mitochondrial fractions; ubiquitin activity was also increased in isolated adult mouse CMs (Figure 7B, lane 8). Moreover, the AMPKα2 overexpression-enhanced role of the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway was more obvious in the presence of CCCP (Figure 7C, lane 8), indicating that AMPKα2 affects this pathway under stressful conditions.

Figure 7. AMPKα2 interacts with PINK1 and enhances the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway.

A. Isolated mouse adult CMs were subjected to PE (50 μmol/L, 24 h) stimulation, followed by the induction of mitophagy. Mitophagy induction was performed by treatment with 20 μmol/L CCCP 8 h after PE stimulation. Representative immunoblots of PINK1, Parkin, SQSTM1, AMPKα2, and ETC complex in lysates of cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions in CMs are shown. B. HL-1 CMs were infected with an adenovirus encoding AMPKα2 (ad-AMPKα2) and then subjected to PE (50 μmol/L, 24 h) stimulation, followed by 20 μmol/L CCCP treatment for 8 h. Representative immunoblots of PINK1, p-Parkin S65, Parkin, SQSTM1, p-AMPKα2, AMPKα2, and anti-ubiquitin in lysates of cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions in CMs are shown. C. Representative immunoblots of PINK1, p-Parkin S65, Parkin, SQSTM1, p-AMPKα2, AMPKα2, and anti-ubiquitin in lysates of mitochondrial fractions in CMs are shown. D–E. HL-1 cells were treated with PE (0, 10, or 50 μmol/L) in the presence or absence of CCCP (20 μmol/L) for 8 h and subsequently subjected to immunoprecipitation with the anti-PINK1 antibody to evaluate its interaction with AMPKα1 or AMPKα2. F–G. HL-1 cells were transfected with ad-Flag-PINK1 and ad-myc-AMPKα2 for 36 hours and then treated with PE (50 μmol/L) in the presence of CCCP (20 μmol/L) for 8 h, followed by immunoprecipitation with the anti-Flag or anti-myc antibody, respectively. H. HL-1 cells were infected with ad-AMPKα2 and subjected to PE (50 μmol/L, 24 h) stimulation, followed by induction of mitophagy. The mitochondrial fractions were extracted for immunoprecipitation with AMPKα2-specific antibody or a control IgG, followed by probing with antibodies specific for PINK1. I. Relative binding between PINK1 and AMPKα2 in the indicated groups. *P < 0.05 vs Ad-LacZ group; #P < 0.05 vs PE+Ad-LacZ group. J. Endogenous PINK1 mobility was examined by western blotting. K. Isolated mouse adult CMs were infected with ad-AMPKα2 and treated with PE (50 μmol/L, 24 h) and then with 20 μmol/L CCCP for 8 h; subsequently, they were subjected to SDS-PAGE ± phos-tag and immunoblotted using an anti-PINK1 antibody. Red asterisks show phosphorylated PINK1. L–M. Isolated mouse adult CMs were infected with AMPKα2 short interfering RNA (si-AMPKα2), treated with PE (50 μmol/L, 6 h), subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE ± phos-tag, and then immunoblotted using an anti-PINK1 antibody. Red asterisks show phosphorylated PINK1. All data represent the mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

To determine how AMPKα2 upregulated the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway and subsequent mitophagy, we used co-immunoprecipitation assays to investigate whether AMPKα2 interacted with PINK1 in adult mouse CMs in vitro. Endogenous PINK1 specifically interacted with AMPKα2, but not AMPKα1, in PE-induced CMs (Figure 7D); these effects were more pronounced in the presence of CCCP (Figure 7E). Increasing the dose of PE reduced the interactions between PINK1 and AMPKα2. Treatment with 50 μmol/L PE substantially inhibited the interactions between PINK1 and AMPKα2; this effect was more pronounced in the presence of CCCP (Figure 7D–E, lane 6). In HL-1 cells, exogenous PINK1-flag and AMPKα2-myc studies also demonstrated the binding of AMPKα2 to PINK1 (Figure 7F–G). In mitochondrial fractions HL-1 cells, the overexpression of AMPKα2 prevented the PE-induced inhibition of the interactions between PINK1 and AMPKα2 (Figure 7H–I, lane 8). To determine whether PINK1 phosphorylation occurred after AMPKα2 modification, we performed PAGE that was conjugated with phos-tag. When exogenous PINK1 was subjected to PAGE with a phos-tag, a clear mobility shift was observed in PINK1. However, after 24 h of PE stimulation, no CCCP-induced mobility shifts in PINK1 were observed, suggesting that PINK1 is phosphorylated following CCCP treatment and that 24 h of PE treatment inhibits this phosphorylation (Online Figure IX C). After overexpressing AMPKα2, a mobility shift in PINK1 was again observed in late PE-induced HL-1 cells after CCCP treatment (Figure 7J, lane 4), indicating that AMPKα2 induces the phosphorylation of PINK1. Furthermore, in CCCP-treated adult mouse CMs, 24 h of PE stimulation resulted in a reduced PINK1 doublet on a conventional 8% PAGE, and the upper band was not found in phos-tag-PAGE (Figure 7K, lane 2). The phosphorylated PINK1 band, however, was partially rescued in an 8% phos-tag-PAGE after overexpression of AMPKα2 (Figure 7K, lane 4). In contrast, 6 h of PE treatment resulted in an increased PINK1 doublet on a conventional 8% PAGE; the upper band was slowed in phos-tag-PAGE (Figure 7L–M, lane 2). Treatment with si-AMPKα2 led to an absence of phosphorylated PINK1 in adult mouse CMs (Figure 7L–M, lane 4), suggesting that AMPKα2 is required for the phosphorylation of PINK1. Overall, these data suggest that AMPKα2 interacts with and phosphorylates PINK1, thereby enhancing the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway to increase mitophagy in PE-stimulated CMs.

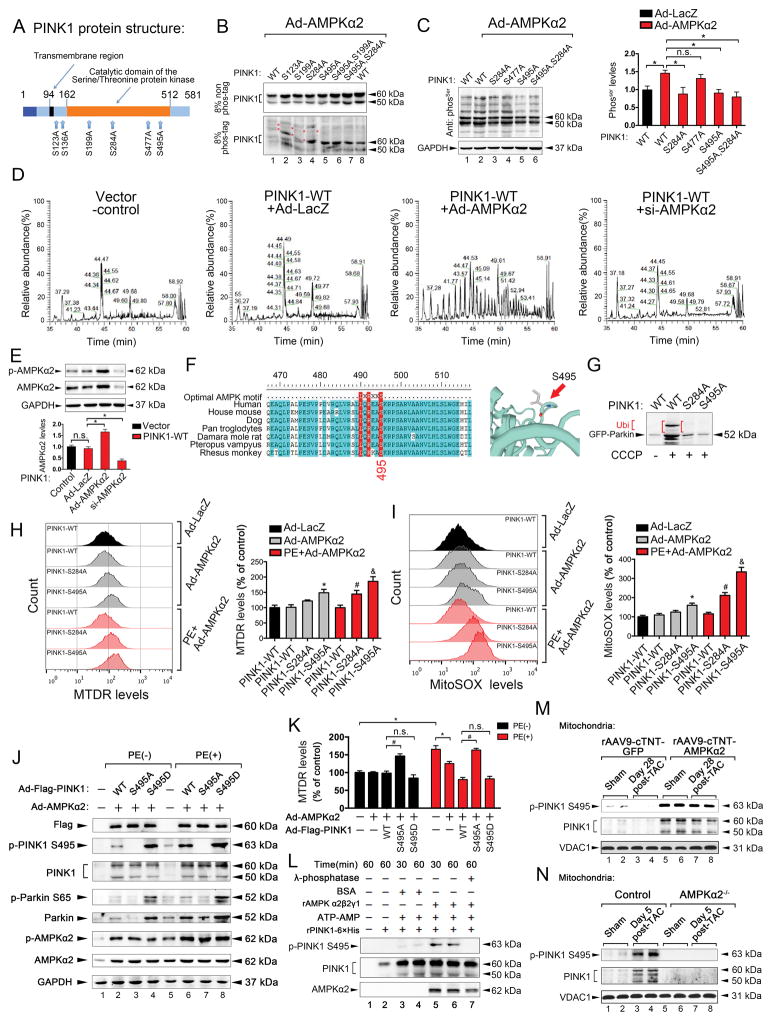

AMPKα2 activates PINK1 mainly by phosphorylating Ser495 to enhance mitophagy and attenuate mitochondrial dysfunction

To understand the mechanism underlying the phosphorylation of PINK1 by AMPKα2, we investigated the AMPKα2 phosphorylation sites on PINK1. By using the phosphorylation prediction software GPS 3.0, we obtained a series of potential AMPKα2 phosphorylation sites of PINK1 and selected the six highest ranking sites (Ser123, Ser136, Ser199, Ser284, Ser477, and Ser495; Figure 8A). We consequently replaced these Ser residues with Ala. Mutation of the AMPKα2 consensus sites (Ser123 and Ser199) in PINK1 did not have a substantial effect on PINK1 phosphorylation by AMPKα2 in CMs. The Ser284Ala mutation had a slight effect on PINK1 phosphorylation. However, the Ser495Ala mutation resulted in a substantial reduction in PINK1 phosphorylation by AMPKα2 in HL-1 cells. The Ser284Ala and Ser495Ala double mutant showed no decreases in PINK1 phosphorylation by AMPKα2 in HL-1 cells (Figure 8B), indicating that the Ser495 site has an important role in phosphorylation. Additionally, anti-serine levels were reduced by AMPKα2 in both Ser284Ala and Ser495Ala mutants (Figure 8C). To further confirm the phosphorylation of PINK1 by AMPKα2 in HL-1 cells, LC-MS/MS detection was performed. AMPKα2 overexpression showed a greater increase in base peaks than ad-LacZ for PINK1 (Figure 8D–E), suggesting that PINK1 is modified by AMPKα2. Of the ten highest ranking phosphorylated peptides by AMPKα2, PINK1 Ser495, Ser284, and Ser228 were also phosphorylated by AMPKα2. Furthermore, Ser228 was autophosphorylated by PINK1 (Online Table III). Ser495 was evolutionarily conserved and was an optimal AMPK substrate, according to a multiple sequence alignment of PINK1 residues neighboring Ser495 in various organisms (Figure 8F). Thus, AMPKα2 activated PINK1 mainly by phosphorylating Ser495 in CMs.

Figure 8. AMPKα2 phosphorylates PINK1 on Ser495 to enhance mitophagy and attenuate mitochondrial dysfunction.

A. Schematic representation of the human PINK1 protein. B. HL-1 cells expressing PINK1-myc with various mutations were infected with an adenovirus encoding AMPKα2 (ad-AMPKα2), subjected to SDS–PAGE ± phos-tag, and immunoblotted using an anti-PINK1 antibody. Red asterisks show phosphorylated PINK1. C. HL-1 cells expressing PINK1-myc with various mutations were infected with ad-AMPKα2 and immunoblotted using an anti-Ser antibody. D. Representative images of base peaks in indicated groups by LC-MS/MS analysis. E. Representative immunoblots of p-AMPKα2 and AMPKα2 after ad-AMPKα2 or si-AMPKα2 stimulations in HL-1 CMs from (D). F. Multiple sequence alignment of PINK1 residues neighboring Ser495 from various organisms. Ser495 appears to have been evolutionarily conserved across most species. G. HL-1 cells expressing GFP-Parkin were infected with ad-PINK1 harboring the Ser284Ala or Ser495Ala mutation, subjected to 20 μmol/L CCCP induction for 8 h, and then immunoblotted with an anti-Parkin antibody. Ub shows ubiquitylation of GFP-Parkin. H. Isolated mouse adult CMs expressing PINK1-myc with Ser284Ala or Ser495Ala mutation were infected with ad-AMPKα2 and subjected to PE (50 μmol/L) stimulation for 24 h. Representative contour plots of CMs stained with MitoTracker are shown, and the MFIs of MitoTracker Deep Red are depicted. *P < 0.05 vs. PINK1-WT in ad-AMPKα2 group; #P < 0.05 vs. PINK1-WT in PE+ad-AMPKα2 group; &P < 0.05 vs. PINK1-WT in PE+ad-AMPKα2 group. I. CMs from (H) were subjected to mitoSOX red staining by FACS. *P < 0.05 vs. PINK1-WT in ad-AMPKα2 group; #P < 0.05 vs. PINK1-WT in PE+ad-AMPKα2 group; &P < 0.05 vs. PINK1-WT in PE+ad-AMPKα2 group. J. Representative immunoblots of p-PINK1 S495, PINK1, p-Parkin S65, Parkin, p-AMPKα2, and AMPKα2 after PINK1-WT, PINK1-S495A, and PINK1-S495D stimulations in HL-1 CMs. K. MFIs of MitoTracker Deep Red after PINK1-WT, PINK1-S495A, and PINK1-S495D stimulations in HL-1 CMs are shown. L. Representative immunoblots for p-PINK1 Ser495 and total levels of PINK1 recombinant proteins with or without AMPKα2β2γ1 co-incubation in a cell-free system are shown. M–N. Representative immunoblots for p-PINK1 Ser495 and PINK1 after gain- and loss-of-function of AMPKα2 in vivo (n=5). All data represent the mean ± SEM from at least four independent experiments.

Next, we examined the functional role of Ser284 and Ser495 phosphorylation in PINK1 activation. The PINK1-stimulated ubiquitination of Parkin was decreased in Ser495Ala and Ser284Ala mutants; Ser495Ala showed more pronounced effects than Ser284Ala (Figure 8G). Under physiological conditions, PINK1 Ser284Ala did not alter mitochondrial contents, but PINK1 Ser495Ala resulted in increased mitochondrial contents in adult mouse CMs. Under PE-induced conditions, PINK1 Ser495Ala and Ser284Ala both increased mitochondrial contents after AMPKα2 overexpression (Figure 8H). Additionally, mitochondria-derived ROS production was increased in PINK1 Ser495Ala under physiological conditions. However, PINK1 Ser495Ala and Ser284Ala both resulted in increased mitochondria-derived ROS production in PE-induced adult mouse CMs. PINK1 Ser495Ala induced higher levels of ROS production than Ser284Ala (Figure 8I). Furthermore, Ser495Ala reduced PINK1 activities (reflected by p-Parkin S65) after AMPKα2 overexpression (Figure 8J), accompanied by increased mitochondrial content (Figure 8K) and reduced mitophagy levels (Online Figure IX G) in PE-treated HL-1 cells. In contrast, Asp (phosphorylation-mimic) mutation of PINK1 Ser495 promoted mitophagy (Online Figure IX G). Recombinant functional AMPKα2β2γ1 directly bound to and phosphorylated PINK1 at Ser495 (Figure 8L). In vivo, PINK1 Ser495 was also phosphorylated by overexpression of AMPKα2 after TAC, but this phosphorylation effect was abolished in AMPKα2−/− mice (Figure 8M–N). These data suggest that overexpression of AMPKα2 mainly phosphorylates PINK1 Ser495 to remove damaged mitochondria, enhance mitophagy, and attenuate mitochondrial dysfunction in CMs under stressful conditions.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we show that AMPKα2 phosphorylated PINK1 to attenuate HF by improving cardiac mitophagy levels. Mechanistically, in the failing heart, the predominant AMPKα isoform switched from AMPKα2 to AMPKα1. This AMPKα isoform switch resulted in suppressed AMPKα2 activity and an impairment of mitophagy in the heart, leading to an accelerated progression to HF. However, the overexpression of AMPKα2 rescued the impairment of mitophagy by phosphorylating PINK1 at Ser495, thereby stimulating the PINK1-Parkin-SQSTM1 pathway to increase mitochondrial autophagy. The increase in cardiac mitophagy level caused the removal of damaged mitochondria and improved mitochondrial function. Our proposed model for the mechanism by which AMPKα2 mediates a protective effect against HF by increasing mitophagy is summarized in Online Figure X.

The word “mitophagy” is a contraction of mitochondria and autophagy and refers to the process by which cells degrade their own mitochondria. The engulfment of mitochondria by autophagosomes and the subsequent transfer to degradative lysosomes can occur during generalized macroautophagy, which may depend on effects such as nutrient deprivation. This process may also occur as a highly selective process that targets dysfunctional mitochondria. Selective mitophagy as a means of mitochondrial quality control was the current focus of our study26, 27.

Previous studies have also revealed that autophagic or mitophagic defects are associated with an increased likelihood for laboratory animals to spontaneously develop specific cardiovascular disorders, including multiple forms of cardiomyopathy. Moreover, the pharmacological or genetic inhibition of autophagy often accelerates disease progression and worsens disease outcome in multiple animal models of cardiovascular disease. Thus, it is necessary to clarify the mechanisms underlying selective mitophagy during the progression of cardiovascular diseases, especially HF. To date, many studies have identified various molecules to be involved in selective mitophagy. For example, aside from the above-mentioned PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy pathway, the partially redundant roles of BCL2 interacting protein 3 like and BCL2 interacting protein 3 may be important in the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis via mitophagy28 in CMs. Additionally, the cardioprotective effects of mitophagy may be partially mediated by FUN14 domain containing protein 1 in mammalian cells29 and in specific models of myocardial infarction30.

Mitochondria are the most important organelles in the regulation of energy generation. Indeed, AMPK is a potent stimulator of autophagy that responds to declining ATP levels by inhibiting mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and directly activating several proteins involved in the initiation of autophagy, including unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase, beclin 1, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 331–33. Although a recent study has reported that AMPK mediates mitochondrial fission in response to energy stress19, it remains unclear whether AMPK has a role in the subsequent mitophagy process during HF.

In agreement with previous observations, we found that the failing heart showed an isoform shift that was accompanied by increases in the expression of AMPKα122, 34 and decreases in the expression of AMPKα2. Recent reports have determined that the ubiquitin ligase Cidea ubiquitinates the β subunit of AMPK, leading to degradation. Atypical ubiquitination has been identified on the α subunit as well as two of the regulatory AMPK kinases, NUAK1 and MARK4, which regulate AMPK activity35, 36. The process of ubiquitination in HF is also dys-regulated37. Thus, we speculated that the reduced expression of AMPKα2 was associated with differential rates of degradation of the α isoforms of AMPK during HF. Reduced AMPKα2 activity in failing hearts resulted in impaired mitophagy, leading to an acceleration of HF progression. AMPKα2 has been suggested to be the more important isoform for determining cardiac function during cardiac stress17. In the current study, AMPKα2 was more important than AMPKα1 in cardio-protection, especially as a regulator of mitochondrial function, which is thought to counteract cardiac remodeling34. Increased expression of AMPKα1 has been shown to promote myocardial activator protein-1 activation in a protein kinase C zeta-dependent manner, thereby contributing to cardiac stress signaling38.

In conclusion, in failing hearts, the dominant AMPKα isoform switched from AMPKα2 to AMPKα1, which accelerated HF. Our data define an important relationship between AMPKα2 and PINK1 and have identified a novel mechanism showing the anti-HF effects of these proteins. Although AMPKα2 is a highly-conserved sensor of mitochondrial damage across eukaryotes, PINK1 is one of the first AMPKα2 substrates to be discovered to directly control mitophagy during HF. We conclude that phosphorylation of Ser495 in PINK1 by AMPKα2 is essential for efficient mitophagy to prevent the progression of HF and provide a potential therapeutic strategy by upregulating AMPKα2

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a common cause of heart failure (HF).

Activation of 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) can prevent HF and increase general autophagy.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Isoform shift of the predominant AMPKα2 to the AMPKα1 was observed in the failing hearts from HF patients and in mice subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC).

AMPKα2 regulates cardiac mitophagy during TAC-induced HF in mice.

Genetic knockdown of AMPKα2, but not AMPKα1 by siRNA, suppressed phenylephedrine (PE)-induced mitophagy.

AMPKα2 specifically interacted with and phosphorylated PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) at Ser495 after PE stimulation, and in turn, enhanced the role of the PINK1-Parkin-Sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1) pathway involved in cardiac mitophagy.

This study investigated the roles of AMP kinase (AMPK) subunit α1 and α2 in heart failure (HF), specifically in terms of mitophagy. We found that HF is accompanied by an isoform switch from AMPKα2 to AMPKα1. AMPKα2 was associated with increased mitophagy and attenuation of HF symptoms, whereas AMPKα1 expression was associated with increased HF severity. This could be related to the phosphorylation of PINK1 by AMPKα2 and the resultant activation of the mitophagy pathway. Overexpression of AMPKα2 in failing heart cardiac myocytes reversed the effects of HF and improved mitochondrial function and mitophagy. These results identify AMPKα2 as an important factor in preventing and reducing HF symptoms, and raise the possibility that therapies targeted to AMPKα2 could repair cardiac myocytes during the onset of HF.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81630010, 91439203 and 31571197), the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2012CB518004), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2015ZDTD044). Dr. Ming-Hui Zou’s work was supported by NIH grants (HL079584, HL080499, HL089920, HL110488, CA213022, AG047776 and HL128014, HL132500, and HL137371).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- HF

heart failure

- CM

cardiomyocyte

- AMPK

AMP-activated protein kinase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- PINK1

PTEN-induced putative kinase-1

- SQSTM1

sequestosome-1

- ΔΨm

mitochondrial transmembrane potential

- WT

wild-type

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- β-MHC

beta-myosin heavy chain

- LVPW

left ventricular posterior wall

- LVEDP

left ventricular end diastolic pressure

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- VDAC

voltage-dependent anion channel

- PE

phenylephedrine

- TAC

transverse aortic constriction

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

- LC3

light chain 3

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVFS

left ventricular fractional shortening

- CCCP

carbonyl cyanide p-trichloromethoxyphenylhydrazone

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Bei Wang designed and performed all the animal and in vitro experiments and drafted the manuscript. Jiali Nie helped perform TAC surgery in mice. Lujin Wu and Zheng Wen assisted the in vitro experiments, and Yangyang Hu assisted with the confocal microscope experiments. Chen and Lingli Dong were involved in the design and data interpretation processes. Dao Wen Wang and Chen Chen are corresponding authors who provided financial support, designed the study, and completed the writing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Jr, Drazner MH, et al. 2013 accf/aha guideline for the management of heart failure: Executive summary: A report of the american college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810–1852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2008 update: A report from the american heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2008;117:e25–146. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.187998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenthal MJ. Mitochondrial involvement in myocyte death and heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2016;21:137–155. doi: 10.1007/s10741-016-9531-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasquez-Trincado C, Garcia-Carvajal I, Pennanen C, Parra V, Hill JA, Rothermel BA, et al. Mitochondrial dynamics, mitophagy and cardiovascular disease. J Physiol. 2016;594:509–525. doi: 10.1113/JP271301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cahill TJ, Leo V, Kelly M, Stockenhuber A, Kennedy NW, Bao L, et al. Resistance of dynamin-related protein 1 oligomers to disassembly impairs mitophagy, resulting in myocardial inflammation and heart failure. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:25762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.A115.665695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda Y, Shirakabe A, Maejima Y, Zhai P, Sciarretta S, Toli J, et al. Endogenous drp1 mediates mitochondrial autophagy and protects the heart against energy stress. Circ Res. 2015;116:264–278. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oka T, Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Taneike M, Takeda T, Tamai T, et al. Mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy causes inflammation and heart failure. Nature. 2012;485:251–255. doi: 10.1038/nature10992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitada T, Asakawa S, Hattori N, Matsumine H, Yamamura Y, Minoshima S, et al. Mutations in the parkin gene cause autosomal recessive juvenile parkinsonism. Nature. 1998;392:605–608. doi: 10.1038/33416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valente EM, Abou-Sleiman PM, Caputo V, Muqit MM, Harvey K, Gispert S, et al. Hereditary early-onset parkinson’s disease caused by mutations in pink1. Science. 2004;304:1158–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.1096284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y, Dorn GW., 2nd Pink1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science. 2013;340:471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okatsu K, Oka T, Iguchi M, Imamura K, Kosako H, Tani N, et al. Pink1 autophosphorylation upon membrane potential dissipation is essential for parkin recruitment to damaged mitochondria. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1016. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hardie DG. Ampk and raptor: Matching cell growth to energy supply. Mol Cell. 2008;30:263–265. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang BB, Zhou G, Li C. Ampk: An emerging drug target for diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2009;9:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carling D. The amp-activated protein kinase cascade--a unifying system for energy control. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hue L, Rider MH. The amp-activated protein kinase: More than an energy sensor. Essays Biochem. 2007;43:121–137. doi: 10.1042/BSE0430121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gustafsson AB, Gottlieb RA. Autophagy in ischemic heart disease. Circ Res. 2009;104:150–158. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.187427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang P, Hu X, Xu X, Fassett J, Zhu G, Viollet B, et al. Amp activated protein kinase-alpha2 deficiency exacerbates pressure-overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction in mice. Hypertension. 2008;52:918–924. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.114702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang B, Zeng H, Wen Z, Chen C, Wang DW. Cyp2j2 and its metabolites (epoxyeicosatrienoic acids) attenuate cardiac hypertrophy by activating ampkalpha2 and enhancing nuclear translocation of akt1. Aging Cell. 2016;15:940–952. doi: 10.1111/acel.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toyama EQ, Herzig S, Courchet J, Lewis TL, Jr, Loson OC, Hellberg K, et al. Metabolism. Amp-activated protein kinase mediates mitochondrial fission in response to energy stress. Science. 2016;351:275–281. doi: 10.1126/science.aab4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doenst T, Nguyen TD, Abel ED. Cardiac metabolism in heart failure: Implications beyond atp production. Circ Res. 2013;113:709–724. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown DA, Perry JB, Allen ME, Sabbah HN, Stauffer BL, Shaikh SR, et al. Expert consensus document: Mitochondrial function as a therapeutic target in heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim M, Shen M, Ngoy S, Karamanlidis G, Liao R, Tian R. Ampk isoform expression in the normal and failing hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1066–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. Ampk and mtor regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hariharan N, Maejima Y, Nakae J, Paik J, Depinho RA, Sadoshima J. Deacetylation of foxo by sirt1 plays an essential role in mediating starvation-induced autophagy in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2010;107:1470–1482. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.227371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kazlauskaite A, Martinez-Torres RJ, Wilkie S, Kumar A, Peltier J, Gonzalez A, et al. Binding to serine 65-phosphorylated ubiquitin primes parkin for optimal pink1-dependent phosphorylation and activation. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:939–954. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bravo-San Pedro JM, Kroemer G, Galluzzi L. Autophagy and mitophagy in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2017;120:1812–1824. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suliman HB, Piantadosi CA. Mitochondrial quality control as a therapeutic target. Pharmacol Rev. 2016;68:20–48. doi: 10.1124/pr.115.011502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial pruning by nix and bnip3: An essential function for cardiac-expressed death factors. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:374–383. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9174-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu L, Feng D, Chen G, Chen M, Zheng Q, Song P, et al. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein fundc1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:177–185. doi: 10.1038/ncb2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W, Siraj S, Zhang R, Chen Q. Mitophagy receptor fundc1 regulates mitochondrial homeostasis and protects the heart from i/r injury. Autophagy. 2017:1–2. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2017.1300224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell RC, Tian Y, Yuan H, Park HW, Chang YY, Kim J, et al. Ulk1 induces autophagy by phosphorylating beclin-1 and activating vps34 lipid kinase. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:741–750. doi: 10.1038/ncb2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, et al. Phosphorylation of ulk1 (hatg1) by amp-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim J, Kim YC, Fang C, Russell RC, Kim JH, Fan W, et al. Differential regulation of distinct vps34 complexes by ampk in nutrient stress and autophagy. Cell. 2013;152:290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Lu Z, Fassett J, Zhang P, Hu X, Liu X, et al. Metformin protects against systolic overload-induced heart failure independent of amp-activated protein kinase alpha2. Hypertension. 2014;63:723–728. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zungu M, Schisler JC, Essop MF, McCudden C, Patterson C, Willis MS. Regulation of ampk by the ubiquitin proteasome system. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pineda CT, Ramanathan S, Fon Tacer K, Weon JL, Potts MB, Ou YH, et al. Degradation of ampk by a cancer-specific ubiquitin ligase. Cell. 2015;160:715–728. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willis MS, Townley-Tilson WH, Kang EY, Homeister JW, Patterson C. Sent to destroy: The ubiquitin proteasome system regulates cell signaling and protein quality control in cardiovascular development and disease. Circ Res. 2010;106:463–478. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voelkl J, Alesutan I, Primessnig U, Feger M, Mia S, Jungmann A, et al. Amp-activated protein kinase alpha1-sensitive activation of ap-1 in cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;97:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.