Abstract

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that GLUT1-mediated erythrocyte sugar transport is more complex than widely assumed and that contemporary interpretations of emergent GLUT1 structural data are incompatible with the available transport and biochemical data. This study examines the kinetic basis of one such incompatibility -transport allostery - and in doing so suggests how the results of studies examining GLUT1 structure and function may be reconciled. Three-types of allostery are observed in GLUT1-mediated, human erythrocyte sugar transport: 1) Exofacial cis-allostery in which low concentrations of extracellular inhibitors stimulate sugar uptake while high concentrations inhibit transport; 2) Endofacial cis-allostery in which low concentrations of intracellular inhibitors enhance cytochalasin B binding to GLUT1 while high concentrations inhibit binding and, 3) Trans-allostery in which low concentrations of ligands acting at one cell surface stimulate ligand binding at or sugar transport from the other surface while high concentrations inhibit these processes. We consider several kinetic models to account for these phenomena. Our results show that an inhibitor can only stimulate then inhibit sugar uptake if: 1) the transporter binds 2 or more molecules of inhibitor; 2) high affinity binding to the first site stimulates transport and, 3) low affinity binding to the second site inhibits transport. Reviewing the available structural, transport and ligand binding data, we propose that exofacial cis-allostery results from cross-talk between multiple, co-existent ligand interaction sites present in the exofacial cavity of each GLUT1 protein whereas trans-allostery and endofacial cis-allostery require ligand-induced subunit-subunit interactions.

Keywords: kinetic analysis, glucose transport, facilitated diffusion, membrane transport protein, allostery

Introduction

Human erythrocyte facilitative sugar transport is mediated by the sugar transport protein GLUT1 (1, 2) and displays three-types of allostery: 1) Exofacial cis-allostery in which low concentrations of extracellular maltose and WZB117 stimulate sugar uptake while high concentrations inhibit transport (3–5); 2) Endofacial cis-allostery in which low concentrations of intracellular inhibitors such as forskolin and related molecules enhance binding of the intracellular inhibitor cytochalasin to GLUT1 while high concentrations inhibit binding (6, 7) and, 3) Trans-allostery in which low concentrations of ligands such as cytochalasin B or forskolin acting at one cell surface stimulate ligand binding at or sugar transport from the other surface while high concentrations inhibit these processes (4, 7, 8). These behaviors are incompatible with the predictions of the simple/alternating access (9–11) and the fixed site transporters (12, 13) and are routinely ignored in discussions of emergent glucose transport structures (14–17) (but see (18, 19)).

The present study considers several kinetic explanations for GLUT1 allostery. These models range from the simple, alternating access transporter (AAT, which alternately exposes an exofacial sugar binding site or an endofacial sugar binding site) and the fixed site transporter (FST, which simultaneously exposes exo-and endo-facial sugar binding sites) through progressively more complex variants of the AAT and FST presenting catalytic and allosteric ligand binding sites at either side of the membrane. We conclude that an exofacial or endofacial inhibitor can only stimulate then inhibit sugar uptake if: 1) the transporter binds 2 or more molecules of inhibitor at exofacial or endofacial binding sites respectively; 2) high affinity binding to the first site stimulates transport and, 3) low affinity binding to the second site inhibits transport.

We then examine available structural, transport and biochemical evidence and propose: 1) that exofacial cis-allostery is an intramolecular phenomenon; 2) that trans-allostery and endofacial-cis allostery are intermolecular behaviors, and 3) that the available data may be reconciled by a model in which the transporter comprises an oligomer of interacting subunits in which each subunit is an allosteric alternating access transporter.

Methods

Each model was schematized in King-Altman form and then analyzed assuming rapid-equilibrium kinetics or when appropriate by the method of Cha (20, 21). Sugar uptake was expressed as zero-trans sugar uptake (intracellular sugar is absent at zero-time) and cast as the ratio of uptake in the presence of inhibitor (vi) relative to uptake in the absence of inhibitor (vc), i.e. as .

Analysis

Tools

In order to proceed with our analysis we must first consider some of the basic tools employed in studies of GLUT1-mediated sugar transport and ligand binding. These include:

Cytochalasin B (CB) - an “e1” ligand (binds at the endofacial surface of GLUT1) (22–24).

Maltose - an “e2” ligand (cell impermeant and binds at the exofacial surface of GLUT1) (5, 8, 22).

β-D-Glucose (βGlc) and 3-O-methylglucose (3MG) - GLUT1 substrates that bind at both endofacial (e1) and exofacial (e2) binding sites (25, 26).

The human erythrocyte - a cell whose membrane contains approximately 500,000 copies of GLUT1 (27) and whose sugar transport properties have been studied exhaustively (25, 26, 28–30).

-

Purified and membrane-resident GLUT1 - exists in 2 forms of noncovalent oligomers:

Tetramerization-deficient GLUT1 mutants - GLUT1 forms in which membrane spanning helix 9 is substituted with GLUT3 membrane spanning helix 9 resulting in dissociation into GLUT1 dimers (33) and the loss of trans-allostery but retention of exofacial cis-allostery (3).

Models

We must then consider several models for sugar transport:

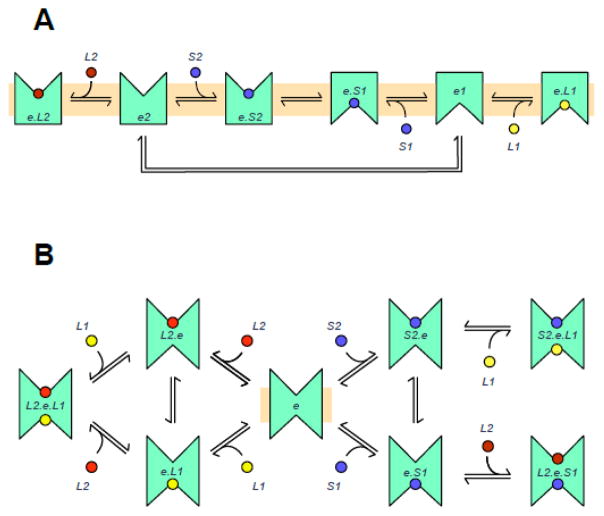

The Simple Carrier The transporter (or carrier, Figure 1A) is an alternating access transporter (AAT; (10)) alternately presenting e2 (external) and e1 (internal) substrate binding sites. Inhibitors bind competitively to e2 and/or e1.

The Fixed Site Transporter (FST) The transporter (Figure 1B) presents sugar uptake and sugar exit sites simultaneously (12). Inhibitor binding at uptake and exit sites is competitive with sugar binding at the same sites.

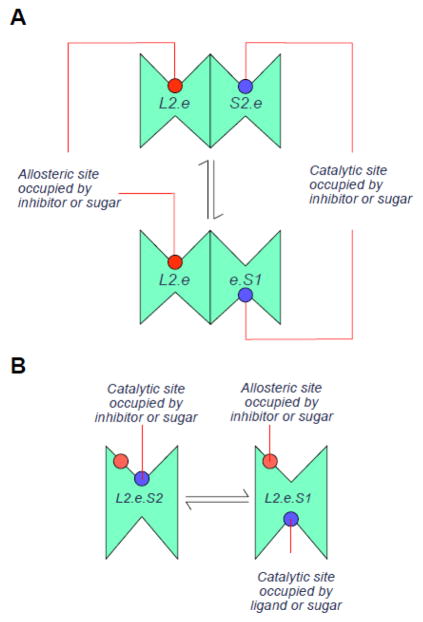

Intermolecular cis-allostery The transporter is an FST but comprises a dimer of FSTs (Figure 2A). The occupancy state of one subunit affects the transport and ligand binding properties of adjacent subunits.

Intramolecular cis-allostery The transporter is an FST but additionally contains an exofacial allosteric activator site (Figure 2B) at which sugar or inhibitors compete for binding and whose occupancy activates transport (either via an affinity or catalytic effect).

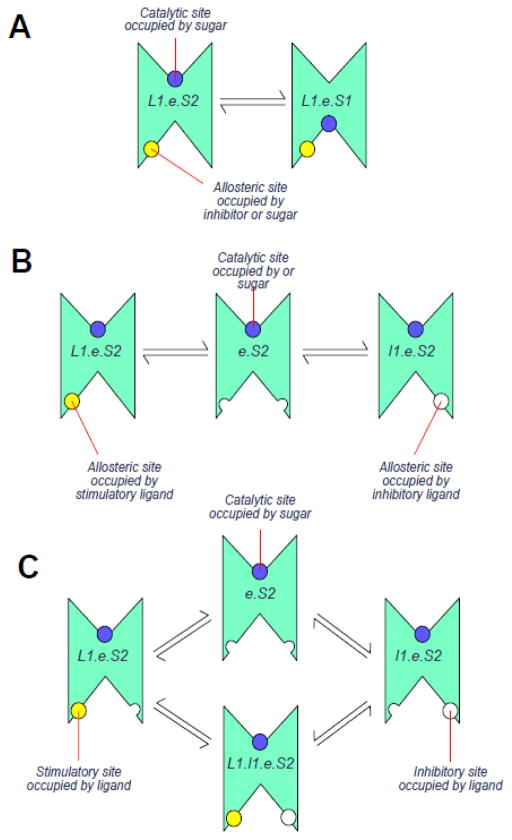

Intramolecular trans-allostery 1 The transporter is an FST. An allosteric activator site that can bind sugar or Inhibitors is present at the endofacial surface of each subunit (Figure 3A) and its occupancy activates transport (either via an affinity or catalytic effect) and enhances ligand binding at the exofacial site.

Intramolecular trans-allostery 2 The transporter is an FST containing endofacial, mutually-exclusive, allosteric sites that can bind sugar or inhibitors (Figure 3B). High affinity occupancy of the first site activates transport. Low affinity occupancy of the second site inhibits transport.

Intramolecular trans-allostery 3 The transporter is an FST containing two allosteric sites that can bind sugar or inhibitors (competitively) at the endofacial surface of each subunit (Figure 3C). High affinity occupancy of the first site activates transport. Low affinity occupancy of the second site inhibits transport. The low affinity site could also represent the endofacial sugar binding site.

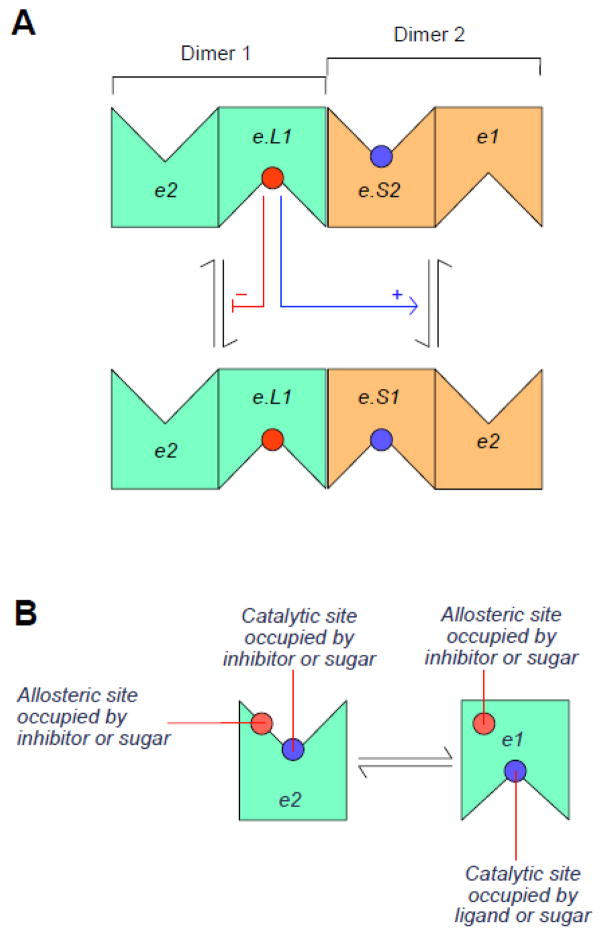

Intermolecular trans-allostery The transporter is a dimer of dimers (a tetramer) of alternating access transporters in which each dimer presents an e2 subunit and an e1 subunit (Figure 4A). If an e1 subunit of a dimer undergoes the e1 to e2 conformational change, the adjacent e2 subunit within the same dimer must undergo the e2 to e1 conformational change. If one dimer contains an inhibitor in the e1 subunit, the dimer is locked in an inactive state. The occupancy states of any one dimer is communicated to the adjacent dimer.

Exofacial, Allosteric Alternating Access Transporter A simple carrier that contains an additional exofacial allosteric site at which sugars and inhibitors compete for binding (Figure 4B). Occupancy of the allosteric site stimulates transport.

Figure 1.

The Alternating Access Transporter (AAT) and the Fixed Site Transporter (FST). A. The AAT. The carrier alternates between conformations exposing an exofacial sugar binding site (e2) and an endofacial sugar binding site (e1). Extracellular inhibitor (L2) and extracellular sugar (S2) compete for binding to e2. intracellular inhibitor (L1) and intracellular sugar (S1) compete for binding to e1. Conformational changes between e2 and e1 are called “translocation” when sugar is bound and “relaxation” when no sugar is bound. B. The FST. The carrier, e, presents exofacial and endofacial sugar binding sites simultaneously. Extracellular sugar (S2) and inhibitor (L2) compete for binding at the exofacial site. Intracellular sugar (S1) and inhibitor (L1) compete for binding at the endofacial site. The carrier can form ternary complexes with intra- and extracellular sugars (S2.e.S1, intra- and extracellular inhibitors (L2.e.L1), or with sugars and inhibitors (L2.e.S1, S2.e.L1).

Figure 2.

A. Intermolecular cis-allostery. The transporter is an FST but comprises a dimer of FSTs (Figure 2A). The occupancy state of one subunit affects the transport and ligand binding properties of adjacent subunits. Thus occupancy of subunit 1 by an exofacial inhibitor to form L2.e traps that subunit in an inhibited state but increases the affinity of the adjacent subunit for extracellular sugar and/or accelerates the rate of transport via the adjacent subunit. B. Intramolecular cis-allostery. The transporter is an FST which additionally contains an exofacial allosteric activator site at which sugars or inhibitors compete for binding and whose occupancy activates transport (either via an affinity or catalytic effect). Thus L2.e.S2 transports faster or with higher affinity for substrate than does e.S2.

Figure 3.

Intramolecular trans-allostery models. A. Model 1. The transporter is an FST. An allosteric activator site that can bind sugar or Inhibitors is present at the endofacial surface of each subunit and, when occupied by ligand, activates transport (either via an affinity or catalytic effect) and enhances ligand binding at the exofacial site. B. Model 2 The transporter is an FST containing mutually-exclusive, endofacial, allosteric sites that can bind sugar or ligands. High affinity occupancy of the first site by an activating ligand (L1) activates transport. Low affinity occupancy of the second site by an inhibitory ligand (I1) inhibits transport. The transporter cannot be occupied by both activator and inhibitor simultaneously. C. Model 3 The transporter is an FST containing two allosteric sites that can bind sugar or inhibitors (competitively) at the endofacial surface of each subunit. High affinity occupancy of the first site by an activator (L1) activates transport. Low affinity occupancy of the second site by an inhibitory ligand (I1) inhibits transport. The transporter may be occupied by both activator and inhibitor simultaneously (forming L1.I1.e) and the net effect on transport depends on the relative potency of activator and inhibitor.

Figure 4.

A. Intermolecular trans-allostery The transporter is a dimer of dimers (a tetramer) of alternating access transporters in which each dimer must present subunits in opposite conformations (e.g. one subunit presents an e2 conformation and the second an e1 conformation or vice versa). If an e1 subunit of a dimer undergoes the e1 to e2 conformational change, the adjacent e2 subunit within the same dimer must undergo the e2 to e1 conformational change. If a dimer contains an inhibitor in its e1 subunit (e.L1), that dimer is trapped in an inhibited state. If the adjacent dimer does not contain an inhibitory ligand (i.e. its e1 subunit is ligand-free), the occupancy state of the neighboring liganded dimer is communicated to the uninhibited dimer and transport of sugar via the e2 subunit is accelerated either via increased affinity of sugar binding or via increased translocation. B. Exofacial, Allosteric Alternating Access Transporter An AAT containing an additional exofacial allosteric site at which sugars and inhibitors compete for binding. Occupancy of the allosteric site (which may persist throughout the transport cycle) stimulates transport via the catalytic center.

King-Altman Schema

The King-Altman schema corresponding to each of these models are illustrated in Schema 1 through 10 (Figure 5 – 10).

Figure 5.

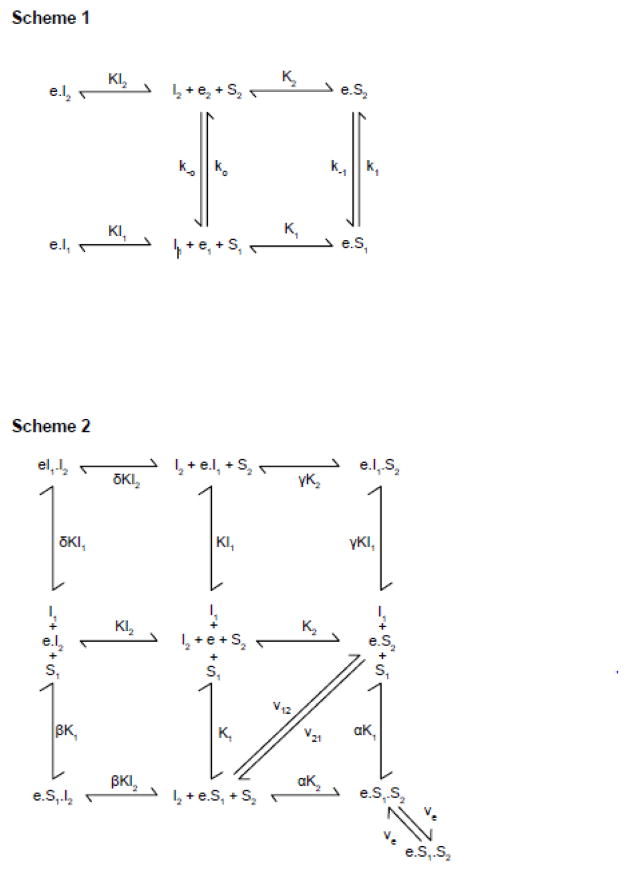

King-Altman representations of the AAT and FST. Scheme 1. The AAT. The carrier e isomerizes between exofacial (e2) and endofacial (e1) conformations. The dissociation constants for extracellular sugar and inhibitor binding to e2 are K2 and KI2 respectively. The dissociation constants for intracellular sugar and inhibitor binding to e1 are K1 and KI1 respectively. First order relaxation rate constants are k−o and ko and first order translocation rate constants are k−1 and k1 Scheme 2. The FST. The carrier e exposes an exofacial site at which extracellular sugar (S2) and inhibitor (I2) compete for binding and an endofacial site at which intracellular sugar (S1) and inhibitor (I1) compete for binding. Dissociation constants for S2, I2, S1 and I1 binding are K2, KI2, K1 and KI1 respectively. Binding of I2 to e affects the dissociation constant for S1 binding by the cooperativity factor β and for I1 binding by the cooperativity factor δ. Binding of I1 to e affects the dissociation constant for S2 binding by the cooperativity factor γ. Binding of S2 to e affects the dissociation constant for S1 binding by the cooperativity factor α. kcat for net sugar import, net sugar export and for exchange transport are v21, v12 and ve respectively.

Figure 10.

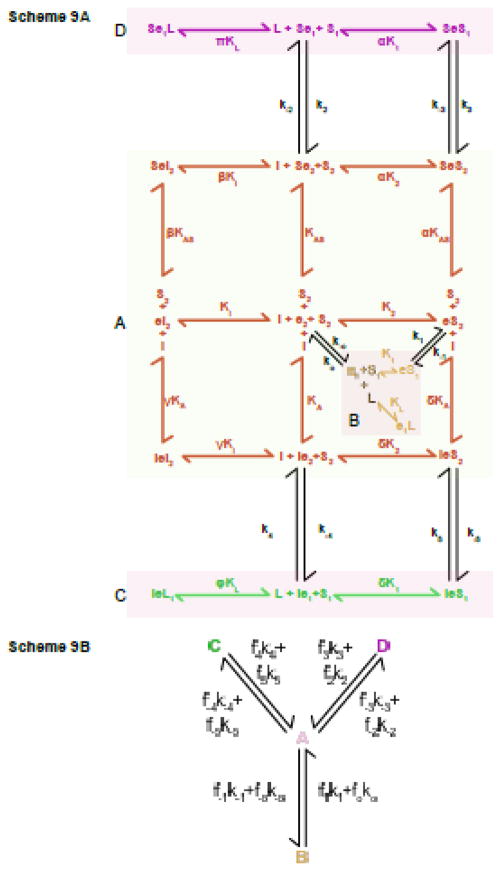

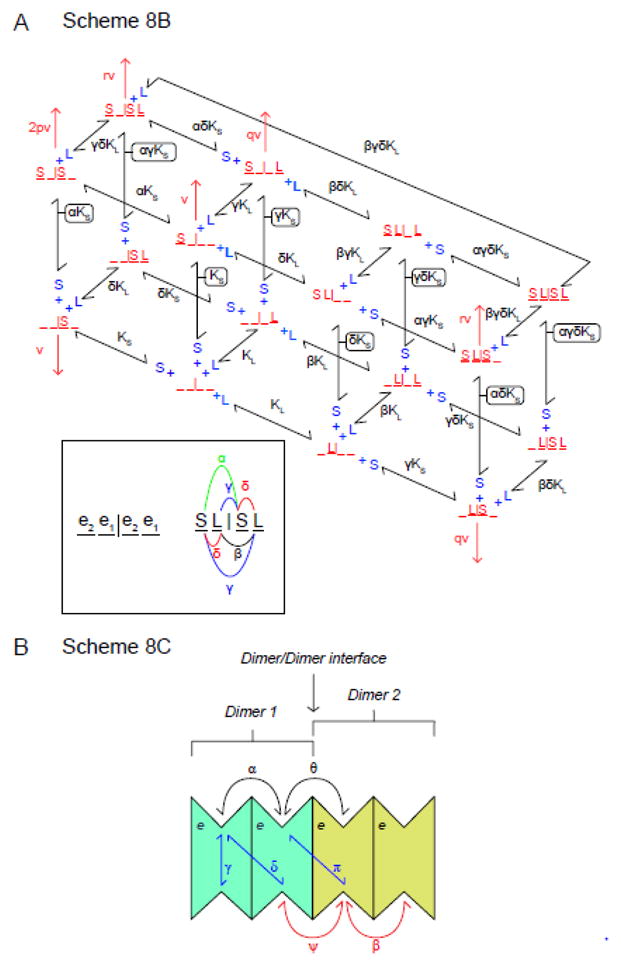

King-Altman representation of the exofacial allosteric AAT. Scheme 9A A simple carrier that contains an additional exofacial allosteric site at which sugars and inhibitors compete for binding. Occupancy of the allosteric site stimulates transport. Ligand binding to the catalytic center is shown as an addition to the right of e. Ligand binding to the allosteric site is shown as an addition to the left of e. Dissociation constants for S1, S2 and I (exofacial inhibitor) binding to e are as described in Figure 5 (K1, K2 and Ki respectively). Intracellular inhibitor (L) binding to e1 is described the the dissociation constant KL. Dissociation constants for S2 and I binding to the exofacial allosteric site are KAS and KA respectively. Binding of I to the allosteric site affects the dissociation constant for S2 and I binding to the catalytic center of e2 by the cooperativity factors δ and γ respectively. Binding of S2 to the allosteric site affects the dissociation constant for S2 and I binding to the catalytic center of e2 by the cooperativity factors α and β respectively. When the allosteric site is occupied by S2 the relaxation rate constants (ko and k−o) become k2 and k−2 and the translocation rate constants (k1 and k−1) become k3 and k−3. Dissociation constants for L and S1 binding to Se1 are affected by the cooperativity factors π and α respectively. When the allosteric site is occupied by I the relaxation rate constants (ko and k−o) become k4 and k−4 and the translocation rate constants (k1 and k−1) become k5 and k−5. Dissociation constants for L and S1 binding to Ie1 are affected by the cooperativity factors φ and δ respectively. The law of microscopic reversibility requires the following: K2 k−2 k3 = K1 k2 k−3 and K2 k−4 k5 = K1 k4 k−5. Scheme 10B A simplified version of Scheme 9A according to the method of Cha. Scheme 9A is subdivided into 4 rapid equilibrium segments - A, B, C and D (see Scheme 9A). The components of segments A, B, C and D (that interchange with other segments via the indicated first order rate constants are described in the solution to Model 9.

Results

Both the alternating access transporter (model 1) and the fixed site transporter (model 2) have been analyzed previously (4, 5, 7, 8, 12, 22, 34) and neither can reproduce transport stimulation at low [inhibitor] followed by inhibition at higher [inhibitor] without significant modification. Only transport inhibition is possible with either of these models when inhibitors (cis or trans) are introduced (22).

Our general conclusion from the subsequent analyses we present below is that when the effect of inhibitor on transport is cast as the ratio of inhibited sugar uptake (vi): control sugar uptake (vc) the equations that reproduce stimulation followed by inhibition take one of two general forms. In the absence of transbilayer sugar leakage (i.e. when non GLUT1-mediated sugar trans-bilayer diffusion is absent)

| eqn 1 |

Or, when non-specific leakage of sugar across the cell membrane is considered,

| eqn 2 |

where the specific interpretation of Const1 – Const4 is model-dependent. An extension of equation 1 also results when the transporter can bind multiple ligands and transported sugars (see result for model 8C).

Solutions for models 3 – 9

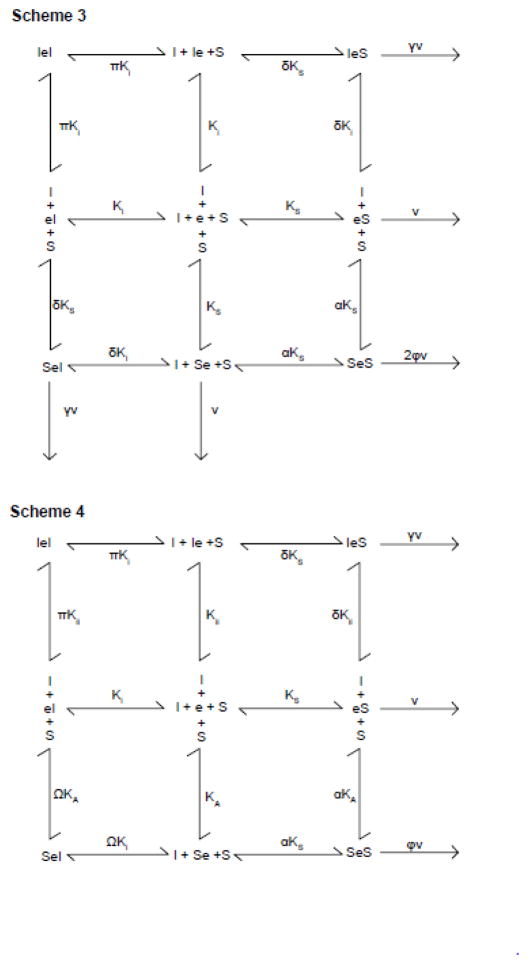

Model 3 - Intermolecular cis-allostery

Assuming rapid equilibrium kinetics, sugar uptake in the presence of extracellular inhibitors (vi) is given by

| eqn 3 |

where [e]t is the concentration of membrane resident GLUT1, [S] and [I] are concentrations of extracellular transported sugar and transport inhibitor respectively and the remaining constants are as defined in Scheme 3. When inhibitors are absent, control uptake (vc) is given by

| eqn 4 |

Thus the ratio of inhibited to control transport is given by:

| eqn 1 |

Where the constants have the following solutions:

This model successfully reproduces transport stimulation followed by transport inhibition as [I] is raised from 0 to saturating levels but seems unlikely given that cis-allostery persists in the GLUT1 tetramerization-null mutant (3).

Model 4 - Intramolecular cis-allostery

Assuming rapid equilibrium kinetics, sugar uptake in the presence of extracellular inhibitors (vi) is given by

| eqn 5 |

where [e]t is the concentration of membrane resident GLUT1, [S] and [I] are concentrations of extracellular transported sugar and transport inhibitor respectively and the remaining constants are as defined in Scheme 4. When inhibitors are absent, control uptake (vc) is given by:

| eqn 6 |

Thus the ratio of inhibited to control transport is given by:

| eqn 1 |

Where the constants have the following solutions:

This reproduces transport stimulation followed by transport inhibition as [I] is raised from 0 to saturating levels (the equation is of the correct form) and is consistent with the finding that the exofacial cavity presents 3 sugar binding sites - peripheral (P), intermediate (I) and core (C) (3, 4). The core site is proposed to be catalytic and the peripheral and intermediate are thought to be allosteric (maltose, WZB117 and other molecules can occupy P+I and I+C; (3–5).

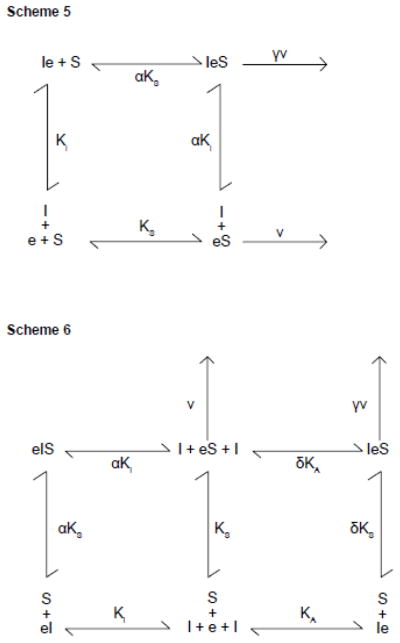

Model 5 - Intramolecular trans-allostery 1

Assuming rapid equilibrium kinetics, uptake (vi) in the presence of intracellular inhibitors (I) is given by:

| eqn 7 |

where [e]t is the concentration of membrane resident GLUT1, [S] and [I] are concentrations of extracellular transported sugar and intracellular transport inhibitor respectively and the remaining constants are as defined in Scheme 5. When inhibitors are absent, control uptake (vc) is given by:

| eqn 8 |

Thus the ratio of inhibited to control transport is given by:

| eqn 9 |

Where the constants have the following solutions:

Equation 9 can only produce transport inhibition (γ < 1) or stimulation (γ > 1) thus this model is rejected.

Model 6 - Intramolecular trans-allostery 2

Assuming rapid equilibrium kinetics, sugar uptake (vi) in the presence of intracellular inhibitors is given by:

| eqn 10 |

where [e]t is the concentration of membrane resident GLUT1, [S] and [I] are concentrations of extracellular transported sugar and transport inhibitor respectively and the remaining constants are as defined in Scheme 6. When inhibitors are absent, control uptake (vc) is given by

| eqn 11 |

Thus the ratio of inhibited to control transport is given by:

| eqn 9 |

Where the constants have the following solutions:

As with Model 5, Model 6 can only produce transport inhibition (γ < 1) or stimulation (γ > 1) thus this model is rejected.

Model 7 - Intramolecular trans-allostery 3

Assuming rapid equilibrium kinetics, sugar uptake (vi) in the presence of intracellular inhibitors (I) is given by:

| eqn 12 |

where [e]t is the concentration of membrane resident GLUT1, [S] and [I] are concentrations of extracellular transported sugar and intracellular transport inhibitor respectively and the remaining constants are as defined in Scheme 7. When inhibitors are absent, control uptake (vc) is given by

Thus the ratio of inhibited to control transport is given by:

| eqn 1.1 |

Where the constants have the following solutions:

When π = 0,

| eqn 1 |

These equations (eqns 1 and 1.1) take the correct form (eqn 1) to permit transport stimulation followed by transport inhibition as [I] is raised from subsaturating to saturating levels. This model seems unlikely, however, because dimeric GLUT1 binds 1 mol CB per mol GLUT1 while tetrameric GLUT1 binds 0.5 mol CB per mol GLUT1 (31, 32). The binding capacity of this carrier would be 2 mol CB per mol GLUT1.

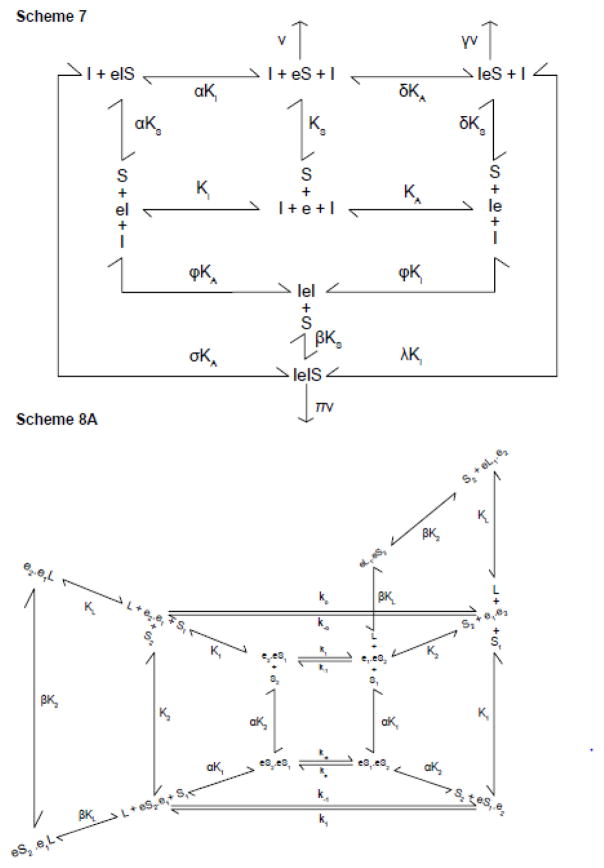

Model 8 - Intermolecular trans-allostery

In this model, the transporter comprises a dimer of GLUT1 dimers. Each dimer is essentially independent of the other although subunit occupancy states are communicated across the dimer/dimer interface. When one e1 subunit of a dimer contains a bound inhibitor (L) its adjacent e2 partner within the dimer (termed the cognate subunit) is, like its liganded partner, locked and thus inactive. However the occupancy state of e1L is transmitted to the adjacent dimer and allows the e2 subunit of the adjacent dimer to bind S2 with higher affinity or to transport S2 (k-1) with greater speed.

This model is more challenging to solve. The probability of dimer 1 or 2 having S2 bound in a catalytically active form is given by

The probability of dimer 1 or 2 having S1 plus S2 bound in a catalytically active form is given by:

The probability of dimer 1 or 2 having L bound is given by

And the probably of either being free of ligand is 1−PL.

Assuming only transport rates are affected (not affinity at this point)

When S1 = 0

| eqn 13 |

| eqn 14 |

| eqn 1.1 |

where

Equation 1.1 is analogous to eqn 1 thereby permitting transport stimulation followed by transport inhibition as [L] is raised from subsaturating to saturating levels.

A variant of this scheme (Scheme 8B) is shown in Figure 9A. Here the tetramer is shown as a dimer of dimers in which each subunit is an AAT but where each dimer adopts the e2.e1 or e1.e2 conformation. There are 4 possible configurations of unliganded tetramer (e2.e1|e2.e1, e2.e1|e1.e2, e1.e2|e2.e1 and e1.e2|e1.e2). The scheme in Figure 9 illustrates only the e2.e1|e2.e1 conformation. It should be noted, however, that this represents only one half cycle of AAT-mediated transport (we assume rapid equilibrium kinetics to simplify the analysis).

Figure 9.

A. Scheme 8C King-Altman representation of alternative model for intermolecular trans-allostery. The transporter comprises a dimer of GLUT1 dimers. Each GLUT1 subunit is an AAT. Each dimer is independent of the other although subunit occupancy states are communicated across the dimer/dimer interface. Each dimer adopts the e2.e1 or e1.e2 conformation. There are 4 possible configurations of unliganded tetramer (e2.e1|e2.e1, e2.e1|e1.e2, e1.e2|e2.e1 and e1.e2|e1.e2). The scheme in here illustrates only the e2.e1|e2.e1 conformation. The unliganded transporter (e2.e1|e2.e1) is depicted as _ _ | _ _ where each underscore represents an unliganded site. An e2 site can become liganded with extracellular sugar S (e.g. S _ | _ _ or _ _ | S _ or S _ | S _) whereas the e1 site can become liganded with L (e.g. _ L | _ _ or _ _ | _ L or _ L | _ L). Only dimers in which the cognate e1 subunit is not complexed with L are capable of transport. Dissociation constants for S and L binding are KS and KL respectively. The inset summarizes cooperative interactions. S biding to one dimer affects S binding to the adjacent dimer by the cooperativity constant α. L biding to one dimer affects L binding to the adjacent dimer by the cooperativity constant β. S and L biding to the same dimer is cooperative and described by the cooperativity constant δ. S and L biding to different dimers within the complex is cooperative and is described by the cooperativity constant γ. The factors p, q and r describe how kcat (v) for sugar uptake by the tetramer is affected when the tetramer contains: 1) 2 sugars, 2) a sugar in 1 dimer plus an inhibitor in the adjacent dimer and 3) 2 sugars and one inhibitor respectively. B. Scheme 8C. A FST tetramer comprising a dimer of FST dimers. This transporter can bind up to 4 exofacial sugars (S) and 4 endofacial ligands (L). Exofacial cooperativity is shared within subunits of each dimer (binding of the first sugar affects KS for binding of the second by the cooperativity factor α) and between dimers (binding of a sugar to one dimer affects KS for binding of a second sugar to a subunit in the adjacent dimer by the cooperativity factor θ. In a similar way, endofacial cooperativity is shared within subunits of each dimer (binding of the first ligand affects KL for binding of the second by the cooperativity factor β) and between dimers (binding of a ligand to one dimer affects KL for binding of a second ligand to a subunit in the second dimer by the cooperativity factor ψ. Finally cooperativity may exist between endofacial and exofacial sites (trans-allostery) within the same subunit (γ) between subunits of the same dimer (δ) and between subunits in different dimers (π).

Assuming rapid equilibrium, uptake in the absence of intracellular inhibitor, L, is given by:

and uptake in the presence of intracellular inhibitor L is described by

Thus vi/vc is:

which reduces to

and subsequently to the form of equation 1

| eqn 1 |

where:

If the trans-action of L is to increase Vmax for net sugar uptake, the parameters q and r > 1 while the cooperativity factors α, β, δ and γ = 1. If the trans-action of L is to increase affinity for substrate in net sugar uptake, the parameters q = r = 1 while the cooperativity factors δ and γ = < 1. This model allows for endofacial cis-allostery when β < 1.

As described, this model is also kinetically equivalent to a dimer of FSTs. While we think the latter model is inappropriate because trans-allostery is lost when GLUT1 forms only dimers (3), this model could be expanded to allow for a tetramer of FSTs in which trans-allostery requires cooperative interactions from all 4 subunits. Such a model (Scheme 8C) is shown in Figure 9B. This transporter can bind up to 4 exofacial sugars (S) and 4 endofacial ligands (L). Exofacial cooperativity is shared within subunits of each dimer (binding of the first sugar affects KS for binding of the second by the cooperativity factor α) and between dimers (binding of a sugar to one dimer affects KS for binding of a second sugar to a subunit in the second dimer by the cooperativity factor θ. In a similar way, endofacial cooperativity is shared within subunits of each dimer (binding of the first ligand affects KL for binding of the second by the cooperativity factor β) and between dimers (binding of a ligand to one dimer affects KL for binding of a second ligand to a subunit in the second dimer by the cooperativity factor ψ. Finally cooperativity could be expressed between endofacial and exofacial sites (trans-allostery) in the same subunit (γ) between subunits of the same dimer (δ) and between subunits in different dimers (π). Since trans-allostery and endofacial cis allostery are absent in dimeric GLUT1, this eliminates a role for trans-cooperativity factors ∂ and γ) and trans-allostery must (according to this model) be strongly dependent on cooperativity factor π. The endofacial cis-allostery constant ψ must be restored to unity in dimeric GLUT1.

Capable of binding up to 8 ligands simultaneously, this transporter complex can exist in as many as 256 (28) different liganded states and the solution is correspondingly complex.

Measuring uptake of extracellular sugar, S, in the absence of intracellular sugar but in the presence of endofacial ligand, L, and assuming that any individual subunit complexed with L is catalytically inactive, the ratio vi/vc is given by:

| eqn 1.2 |

where:

This model allows for trans-allostery (stimulation of sugar uptake by endofacial ligand (e.g. CB) when all allostery constants are set to unity but ∂ (trans allostery between S and L binding sites in neighboring subunits of each dimer) or π (trans allostery between S and L binding sites in subunits of neighboring dimers) are <1. Since trans-allostery is lost in dimeric GLUT1, we assume that ∂ =1 and that π is the dominant trans-cooperativity constant in this model.

Model 9 - Exofacial, Allosteric Alternating Access Transporter

This is a standard alternating access transporter with the proviso that the e2 conformation presents 2 binding sites - an allosteric site which can be occupied by sugar or inhibitor and a catalytic site which can be occupied by sugar or inhibitor. Occupancy of the allosteric site can stimulate or inhibit transport and affect the affinity of the catalytic site in both e1 and e2 for substrate or inhibitor. Occupancy of the allosteric site and its effects persist through the e2 to e1 conformational change. However S or I can only dissociate from the allosteric site in the e2 conformation.

This model is more challenging to solve. Assuming segments A, B, C and D of Scheme 9 (Figure 10) are in rapid equilibrium, we can define the following:

f−1 is fraction of A existing as eS2

f−o is fraction of A existing as e2

f−2 is fraction of A existing as Se2

f−3 is fraction of A existing as SeS2

f−4 is fraction of A existing as Ie2

f−5 is fraction of A existing as IeS2

f1 is fraction of B existing as eS1

fo is fraction of B existing as e1

f4 is fraction of C existing as Ie1

f5 is fraction of C existing as IeS1

f2 is fraction of D existing as Se1

f3 is fraction of D existing as SeS1

The King-Altman figure reduces to Scheme 9B and uptake

where

When S1 = L = I = 0

where

When S1 = I = 0 but L > 0

Thus

Expanding terms then gathering around L terms yields the following:

| eqn 15 |

where

Finally, let’s consider that S1 = L = 0 but I > 0. Under these conditions:

Dividing by vc expanding then gathering terms around I, we obtain:

| eqn 1 |

where

This model explains why exofacial cis-allostery persists in the TM9 (tetramerization-null) mutant (3) and in dimeric GLUT1 (7) and allows for allosteric stimulation of sugar uptake by the transport substrate. The model also explains sugar occlusion in the presence of CB (35). The model does not allow for intramolecular, endofacial trans-allostery because the equation for the effect of L on uptake takes the form

Consideration of non-specific transport

We occasionally observe a component of transport (typically measured as uptake of radiolabeled sugar) that is neither inhibited by saturating concentrations of inhibitors (e.g. cytochalasin B or forskolin) nor by saturating concentrations of sugars (e.g. D-glucose or 3-O-methylglucose) (36). This could represent protein-independent, trans-bilayer diffusion or non-specific association with the cell surface or with plasticware used in transport determinations. Such non-specific “transport” is well-described as

| eqn 16 |

where k is a first order rate constant which is insensitive to inhibitor. We examine the effect of inclusion of non-specific transport in our analyses by reviewing its impact on Model 4 - intramolecular cis-allostery.

Assuming rapid equilibrium kinetics, sugar uptake in the presence of extracellular inhibitors (vi) is given by:

| eqn 17 |

where [e]t is the concentration of membrane resident GLUT1, [S] and [I] are concentrations of extracellular transported sugar and transport inhibitor respectively and the remaining constants are as defined in Scheme 4. When inhibitors are absent, control uptake (vc) is given by:

| eqn 18 |

| eqn 2 |

where:

Behavior of Models

Models 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7 were eliminated in the Results section either because the resulting equations cannot reproduce the transport behavior (Models 1, 2, 5, 6) or because the available biochemical evidence (ligand binding) is incompatible with the model’s predictions (Models 3 and 7). This leaves models 4, 8 and 9 for consideration. Because each of the remaining models is described by a common set of equations, we consider the simplest models for cis-allostery (Model 4) and Trans-allostery (Model 8B) although the general conclusions for Models 4 and 8B are also applicable to Models 9 and 8A/8C respectively.

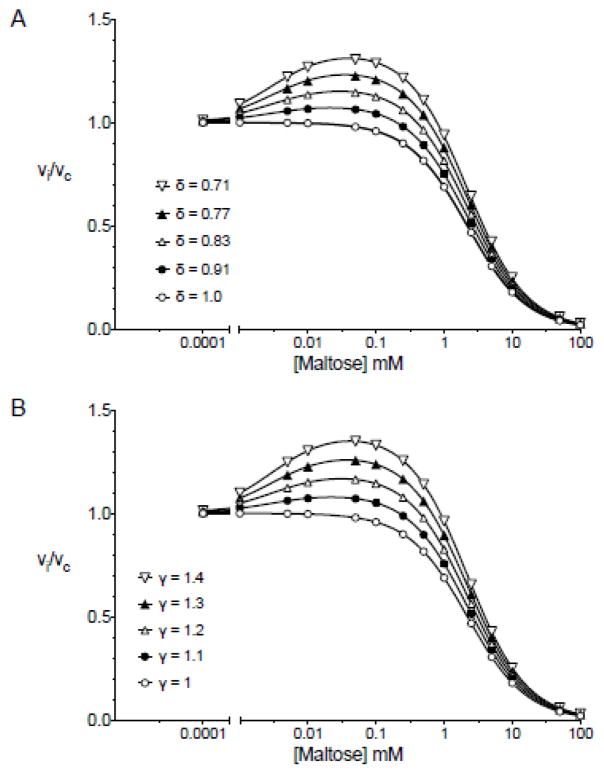

Figure 11A (intramolecular cis-allostery - the affinity affect) illustrates how subsaturating levels of extracellular maltose stimulate GLUT1-mediated 3-O-methylglucose uptake in human erythrocytes then, as extracellular maltose levels increase, how sugar uptake is inhibited. This was modeled simply as two binding sites for maltose - a high affinity allosteric site whose occupancy reduces Kd(app) for 3-O-methylglucose binding to the catalytic center by the factor δ and a lower affinity catalytic site at which maltose and 3-O-methylglucose compete for binding. At low [maltose], the allosteric site is occupied reducing Kd(app) for transport and thus stimulating sub-saturated transport. As [maltose] is further increased, maltose and 3-O-methylglucose compete for binding to the catalytic site and transport is inhibited. Using parameters that are consistent with previously published affinity constants for 3-O-methylglucose and maltose (3–5), Figure 11A (intramolecular cis-allostery - the affinity affect) illustrates that reducing δ from 1 to 0.7 produces a 1.4-fold increase in transport that peaks at approximately 50 μM maltose followed by robust transport inhibition with an IC50 of approximately 5 mM. Conversely, we can model the same effect by eliminating any affect of high affinity maltose binding on 3-O-methylglucose binding (δ is fixed at 1) but progressively increasing γ from 1 to 1.4. (Figure 11B Intramolecular cis-allostery the kcat effect). This increases kcat for transport thereby stimulating transport until [maltose] is increased sufficiently to compete with 3-O-methylglucose for binding at the catalytic center.

Figure 11.

A. Intramolecular cis-allostery - the affinity affect. Subsaturating levels of extracellular maltose stimulate GLUT1-mediated 3-O-methylglucose uptake in human erythrocytes then, as extracellular maltose levels increase, sugar uptake is inhibited. Ordinate: vi/vc. Abscissa: [Maltose] in mM (note the log scale). Equation 1 from Model 4 was used to simulate these data. The following constants were used: [S] = 0.1 mM, KS = 1 mM, KA = 0.05 mM, KI = 2 mM, KII = 0.001 mM, α = Ω = γ = π = φ = 1, δ is varied (see legend). These parameters result in the following: Const1 = 0.99, Const2 (varies from 330 mM−1 to 464.8 mM−1 with increasing δ), Const3 (varies from 330.45 to 342.7 mM−1with increasing δ), Const4 = 150 mM−2. Curves were computed by nonlinear regression using equation 1. B. Intramolecular cis-allostery - the kcat affect. As in Figure 11 A but now δ = 1 and γ is varied (see legend). These parameters result in the following: Const1 = 0.99, Const2 (varies from 330 mM−1 to 462 mM−1 with increasing γ), Const3 = 330.45 mM−1, Const4 = 150 mM−2. Curves were computed by nonlinear regression using equation 1.

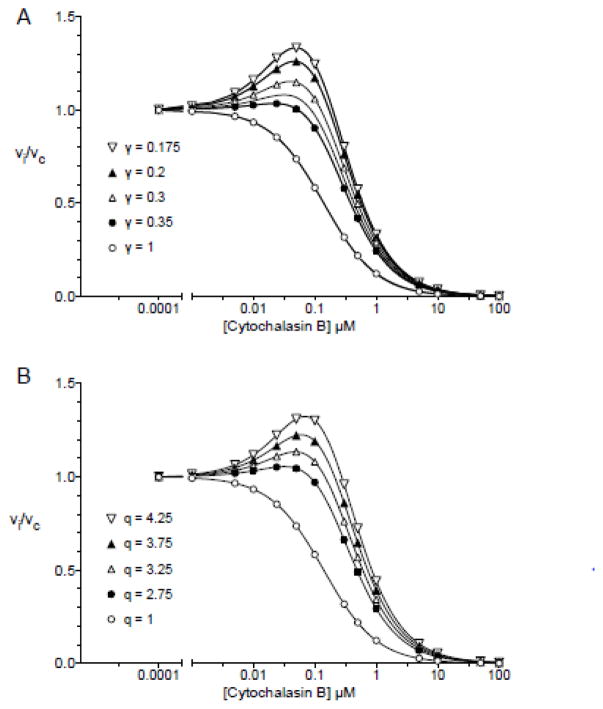

Figure 12 (intermolecular trans-allostery) illustrates how subsaturating levels of cytochalasin B (CB, a ligand that readily crosses the cell membrane to act at an endofacial site on GLUT1 (3, 12)) first stimulate GLUT1-mediated 3-O-methylglucose uptake in human erythrocytes then, as CB levels increase, how sugar uptake is inhibited (3, 4). This was modeled assuming a dimer of GLUT1 dimers. Each dimer is independent of its neighbor although subunit occupancy states are communicated across the dimer/dimer interface. When one e1 subunit of a dimer contains a bound inhibitor (L or CB) its cognate e2 partner (the adjacent subunit in the same dimer) like its liganded partner, is locked and thus inactive. However the occupancy state of e1.L is transmitted to the adjacent dimer and allows the e2 subunit of the adjacent dimer to bind S2 with higher affinity (by the factor γ) or to transport S2 with greater efficiency (by the factor p). Figures 12A and B illustrate how varying either γ (the affinity effect) or p (the kcat effect) affect transport. At low [CB], the probability of only 1 e1 subunit of the tetramer being occupied is high, causing transport via the remaining CB-free dimer to become activated by the factor γ. As [CB] is further increased, the second dimer becomes complexed with CB and transport is inhibited. Using parameters that are consistent with previously published affinity constants for 3-O-methylglucose and CB (3–5), Figure 12 illustrates how reducing γ from 1 to 0.175 (Figure 12A) or increasing p from 1 to 4.25 (Figure 12B) reproduce the 1.3-fold increase in transport that peaks at approximately 25 nM CB followed by robust transport inhibition with an IC50 of approximately 100 – 150 nM.

Figure 12.

A. Intermolecular trans-allostery - the affinity affect. Subsaturating levels of intracellular cytochalasin B stimulate GLUT1-mediated 3-O-methylglucose uptake in human erythrocytes then, as cytochalasin B levels increase, sugar uptake is inhibited. Ordinate: vi/vc. Abscissa: [cytochalasin B] in μM (note the log scale). Equation 1 from Model 8B was used to simulate these data. The following constants were used: [S] = 100 μM, K2 = 1000 μM, KL = 0.14 μM, α = β = δ = p = q = r = 1, γ is varied (see legend). These parameters result in the following: Const1 falls from 2.61 × 107 to 7.99 × 105 μM4 with decreasing γ, Const2 falls from 1.86 × 108 to 3.26 × 107 μM3 with decreasing γ, Const3 falls from 3.73 × 108 to 1.63 × 107 μM3 with decreasing γ, Const4 falls from 1.33 × 109 to 8.32 × 107 μM2 with decreasing γ. Curves were computed by nonlinear regression using equation 1. B. Intermolecular trans-allostery - the kcat affect. Subsaturating levels of intracellular cytochalasin B stimulate GLUT1-mediated 3-O-methylglucose uptake in human erythrocytes then, as cytochalasin B levels increase, sugar uptake is inhibited. Ordinate: vi/vc. Abscissa: [cytochalasin B] in μM (note the log scale). Equation 1 from Model 8B was used to simulate these data. The following constants were used: [S] = 100 μM, K2 = 1000 μM, KL = 0.14 μM, α = β = δ = γ = p = r = 1, q is varied (see legend). These parameters result in the following: Const1 = 2.61 × 107 μM4, Const2 increases from 1.86 × 108 to 7.37 × 108 μM3 with increasing q, Const3 = 3.73 × 108 μM3, Const4 = 1.33 × 109 μM2. Curves were computed by nonlinear regression using equation 1.

Equation 2 obtains when not all transport is inhibited by saturating inhibitors and thus allows for the possibility of non-specific, non-protein-mediated or inhibitor-insensitive sugar transport - a phenomenon that is often observed experimentally (36). Under these circumstances vi/vc does not approach 100% inhibition even at saturating [inhibitor].

Limitations of the analysis

While these considerations support the elimination of models 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7, the remaining models are kinetically indistinguishable. These include model 4 (a fixed site transporter), model 8 (variations of oligomers of alternating access transporters or fixed site transporters) and model 9 (an oligomer of allosteric alternating access transporters). As presented, these analyses do not discriminate between alternating access and fixed site transporter models. Other approaches are necessary to accomplish this (22, 23, 34) and when applied, support the hypothesis that GLUT1 functions as an allosteric fixed site transporter (although they do not consider the possibility that a fixed site transporter could be an oligomeric complex of interacting, alternating access transporters). In the present study, discrimination between models 4, 8 and 9 relies on prior analysis of GLUT1 cytochalasin B binding stoichiometry. This could introduce interpretive problems for two reasons: 1) GLUT1 cytochalasin B binding is also influenced by ATP; 2) The stoichiometry of cytochalasin B binding to GLUT1 monomers, dimers and tetramers may be difficult to measure accurately if GLUT1 affinity for cytochalasin B is affected by its oligomeric state.

Previous studies from this laboratory (5, 7, 8, 37–39) have shown that GLUT1 is a nucleotide binding protein, that ATP binding at an endofacial site increases the affinity of the exofacial site for sugars but reduces Vmax for sugar uptake, reduces cooperativity in cytochalasin B binding to GLUT1 but increases the affinity of the high affinity site for cytochalasin B. Other studies have shown that steroidal ligands (40, 41), caffeine and AMP (42) inhibit ATP binding to GLUT1 thereby altering the kinetics of glucose transport and cytochalasin B binding. It is possible therefore that activation of glucose influx at low cytochalasin B concentrations results from a complex interplay between cytochalasin B and nucleotide binding to GLUT1. We think this unlikely for three reasons: 1) Cytochalasin B and ATP binding to GLUT1 are positively cooperative - cytochalasin B binding at low [cytochalasin B] is enhanced by ATP and ATP binding at subsaturating [ATP] is enhanced by cytochalasin B (7); 2) Low concentrations of extracellular maltose trans-activate cytochalasin B binding to red cell ghosts in the presence and absence of intracellular ATP (5). Sub-saturating [cytochalasin B] stimulates sugar uptake in both ATP-containing and in ATP-free red cell ghosts (5). These results indicate that trans-allostery is not ATP-dependent but may be modulated by ATP.

The question of GLUT1 cytochalasin B binding stoichiometry is more difficult to address when cells typically express a mixture of GLUT1 monomers, dimers and tetramers (43). What is clear, however is that cis-allostery persists but trans-allostery is lost in both reduced (dimeric) and recombinant, tetramerization-deficient GLUT1 (3, 7). Trans-allostery thus requires intermolecular interactions while cis-allostery may dependent on intramolecular interactions.

Detailed analysis by Cunningham and Naftalin (19) of the homology-modeled GLUT1 structure and the T295M GLUT1 deficiency mutation led to the important insight that GLUT1 presents twin glucose entry ports at its external surface which converge on a common catalytic vestibule containing a high affinity glucose binding site. Maltose binding to one entry port could, therefore, increase glucose affinity at the other port and thereby stimulate glucose entry into the catalytic vestibule. Cunningham and Naftalin further noted that the T295M GLUT1 deficiency mutation exhibits high temperature sensitivity and proposed a rationale for this behavior (impaired glucose exchange between vestibules at low temperatures; (19)). Our own studies also suggest the presence of 2 exofacial sugar binding sites that converge on a catalytic site (3, 4) and thus support the Cunningham and Naftalin model. Studies of the temperature-dependence of cis-allostery in the T295M GLUT1 deficiency mutation may allow further review of their model and the roles of the entry ports in cis-allostery.

Conclusions

GLUT1 allostery is explained only by models in which multiple exofacial ligand and multiple endofacial ligand binding sites co-exit. At least one exofacial site and one endofacial site must also correspond to the catalytic site. The endofacial ligand binding properties of GLUT1 (24, 31) and molecular docking studies (3, 4, 42, 44) indicating 1 or fewer cytochalasin B binding sites per GLUT1 molecule eliminate the possibility that more than one e1 ligand can bind to each GLUT1 molecule. This conclusion, in conjunction with the observation that multiple e1 ligand binding sites per transporter are required to explain the transport behavior, suggests that the transporter must comprise an oligomer of interacting GLUT1 proteins. Each subunit (protein) could function as an AAT or an FST. The X-ray crystallography data (3, 14–17) suggest: 1) each GLUT1 molecule is an AAT not FST; 2) the exofacial conformation of GLUT1 presents multiple ligand binding sites; 3) the allosteric endofacial site corresponds to the catalytic site in an adjacent e1 subunit. Previous studies have shown that forskolin-stimulated cytochalasin B binding to GLUT1 is abolished in dimeric (reduced) GLUT1 (7) suggesting that endofacial cis-allostery requires tetrameric GLUT1 and that the endofacial allosteric site is contributed by an adjacent subunit not by the subunit to which ligand binding is measured. If, correct, this behavior (loss of endofacial cis-allostery) should be recapitulated with the TM9 (tetramerization-deficient) mutant, confirming that exofacial cis-allostery is an intramolecular phenomenon but endofacial cis-allostery is intermolecular.

Figure 6.

King-Altman representations of inter- and intramolecular cis-allostery. Scheme 3. Intermolecular cis-allosteryGLUT1 is an FST but the transporter comprises a dimer of FSTs. Binding of extracellular inhibitor (I) or sugar (S) to subunit 1 is represented as an addition to the left of e. Binding of extracellular inhibitor (I) or sugar (S) to subunit 2 is represented as an addition to the right of e. Dissociation constants for I or S binding to either subunit are KI and KS respectively. Binding of S to either subunit affects the dissociation constants for S and I binding to the adjacent subunit by the cooperativity factors α and δ respectively. Binding of I to either subunit affects the dissociation constant for I binding to the adjacent subunit by the cooperativity factor π. kcat for transport by S.e and e.S is v. kcat for transport by S.e.I and I.e.S is γv. kcat for transport by S.e.S is 2φv. Scheme 4. Intramolecular cis-allostery. GLUT1 is an FST which additionally contains an exofacial allosteric activator site at which sugars or inhibitors compete for binding and whose occupancy activates transport (either via an affinity or catalytic effect). Binding of inhibitor (I) or sugar (S) at the allosteric site is shown to the left of e. Binding of inhibitor (I) or sugar (S) at the catalytic center is shown to the right of e. Dissociation constants for I or S binding at the allosteric site are KII and KA respectively. Dissociation constants for I or S binding at the catalytic center are KI and KS respectively. Sugar binding at the allosteric site affects dissociation constants for S and I binding at the catalytic center by cooperativity factors α and Ω respectively. Inhibitor binding at the allosteric site affects dissociation constants for S and I binding at the catalytic center by cooperativity factors δ and π respectively. kcat for transport by e.S is v., for transport by I.e.S is γv and for transport by S.e.S is φv.

Figure 7.

King-Altman representations of intramolecular trans-allostery. Scheme 5. Intramolecular trans-allostery model 1. GLUT1 is an FST which contains an allosteric site for intracellular ligand. Dissociation constants for binding of intracellular inhibitor (I) or extracellular sugar (S) are KI and KS respectively. Binding of S affects the dissociation constant for I binding by the cooperativity factor α and vice versa. kcat for transport by eS is v. kcat for transport by IeS is γv. Scheme 6. Intramolecular trans-allostery model 2. GLUT1 is an FST containing mutually exclusive, endofacial, allosteric activator and inhibitor binding sites at which sugars or inhibitors compete for binding. Occupancy of the activator and inhibitory sites stimulates and inhibits transport respectively. Binding of activating ligand (I) is shown to the left of e (Ie) and of inhibitory ligand (I) to the right of e (eI). Binding of sugar (S) at the catalytic center is shown to the right of e. Dissociation constants for I binding at the activating and inhibitory sites are KA and Ki respectively. The dissociation constant for S binding at the catalytic center is KS. Sugar binding at its catalytic center affects dissociation constants for I binding at the activating and inhibitory sites by cooperativity factors δ and α respectively. kcat for transport by eS is v., for transport by IeS is δv. eIS is catalytically inactive.

Figure 8.

King-Altman representations of intra- and inter-molecular trans-allostery. Scheme 7. GLUT1 is an FST containing two co-existent allosteric sites that competitively bind sugar (S) or inhibitors (I) at the endofacial surface of each subunit. High affinity occupancy of the first site (shown as binding to the left of e) activates transport. Low affinity occupancy of the second site (shown as binding to the right of e) inhibits transport. Binding of sugar (S) at the catalytic center is shown to the right of e. Dissociation constants for I binding at the activating and inhibitory sites are KA and Ki respectively. The dissociation constant for S binding at the catalytic center is KS. Sugar binding at its catalytic center affects dissociation constants for I binding at the activating and inhibitory sites by cooperativity factors δ and α respectively. I binding at the activating site affects the dissociation constant for I binding at the inhibitory site by cooperativity factor φ. The dissociation constant for I binding at the activating site in the eIS ternary complex is affected by the cooperativity factor σ. The dissociation constant for I binding at the inhibitory site in the IeS ternary complex is affected by the cooperativity factor λ. The dissociation constant for S binding at the catalytic center of the IeI ternary complex is affected by the cooperativity factor β. The rule of microscopic reversibility (45) requires that α σ = δ λ = φ β. kcat for transport by eS is v., for transport by IeS is δv and for transport by IeIS is πv. eIS is catalytically inactive. Scheme 8A. Inter-molecular trans-allostery. The transporter comprises a dimer of GLUT1 dimers. Each GLUT1 subunit is an AAT. Each dimer is independent of the other although subunit occupancy states are communicated across the dimer/dimer interface. Inhibitor L interacts only with e1 conformations of GLUT1. When one e1 subunit of a dimer contains a bound inhibitor (L) its adjacent e2 partner within the dimer (termed the cognate subunit) is, like its liganded partner, locked and thus inactive. However the occupancy state of e1L is transmitted to the adjacent dimer and allows the e2 subunit of the adjacent dimer to bind S2 with higher affinity or to transport S2 (k−1) with greater speed. This scheme portrays intracellular ligand (L) and extra- and intracellular sugar (S2 and S1) binding to a single dimer in the tetrameric complex. First-order translocation rate constants for sugar uptake and exit are k−1 and k1 respectively. First order translocation rate constants for relaxation are k−o and ko. Dissociation constants for S1, S2 and L binding to the dimer are K1, K2 and KL respectively. S2 binding to the dimer affects the dissociation constants for S1 and L binding to the adjacent e1 subunit by the cooperativity factors α and β respectively. The law of microscopic reversibility requires the following: ko k−1 K1 = k−o k1 K2. All other microscopic reversibility requirements derive from this specific relationship.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DK36081 and DK44888.

Bibliography

- 1.Kasahara M, Hinkle PC. Reconstitution and purification of the D-glucose transporter from human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:7384–7390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldwin JM, Gorga JC, Lienhard GE. The monosaccharide transporter of the human erythrocyte. Transport activity upon reconstitution. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:3685–3689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd KP, Ojelabi OA, De Zutter JK, Carruthers A. Reconciling contradictory findings: Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) functions as an oligomer of allosteric, alternating access transporters. J Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.815589. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ojelabi OA, Lloyd KP, Simon AH, De Zutter JK, Carruthers A. WZB117 inhibits GLUT1-mediated sugar transport by binding reversibly at the exofacial sugar binding site. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:26762–26772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.759175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamill S, Cloherty EK, Carruthers A. The human erythrocyte sugar transporter presents two sugar import sites. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16974–16983. doi: 10.1021/bi9918792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robichaud T, Appleyard AN, Herbert RB, Henderson PJ, Carruthers A. Determinants of ligand binding affinity and cooperativity at the GLUT1 endofacial site. Biochemistry. 2011;50:3137–3148. doi: 10.1021/bi1020327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cloherty EK, Levine KB, Carruthers A. The red blood cell glucose transporter presents multiple, nucleotide-sensitive sugar exit sites. Biochemistry. 2001;40:15549–15561. doi: 10.1021/bi015586w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sultzman LA, Carruthers A. Stop-flow analysis of cooperative interactions between GLUT1 sugar import and export sites. Biochemistry. 1999;38:6640–6650. doi: 10.1021/bi990130o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lieb WR, Stein WD. Testing and characterizing the simple carrier. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;373:178–196. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jardetzky O. Simple allosteric model for membrane pumps. Nature. 1966;211:969–970. doi: 10.1038/211969a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Widdas WF. Inability of diffusion to account for placental glucose transfer in the sheep and consideration of the kinetics of a possible carrier transfer. J Physiol (London) 1952;118:23–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker GF, Widdas WF. The asymmetry of the facilitated transfer system for hexoses in human red cells and the simple kinetics of a two component model. J Physiol. 1973;231:143–165. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1973.sp010225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker GF, Naftalin RJ. Evidence of multiple operational affinities for D-glucose inside the human erythrocyte membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;550:474–484. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura N, Verdon G, Kang HJ, Shimamura T, Nomura Y, Sonoda Y, Hussien SA, Qureshi AA, Coincon M, Sato Y, Abe H, Nakada-Nakura Y, Hino T, Arakawa T, Kusano-Arai O, Iwanari H, Murata T, Kobayashi T, Hamakubo T, Kasahara M, Iwata S, Drew D. Structure and mechanism of the mammalian fructose transporter GLUT5. Nature. 2015;526:397–401. doi: 10.1038/nature14909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng D, Xu C, Sun P, Wu J, Yan C, Hu M, Yan N. Crystal structure of the human glucose transporter GLUT1. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quistgaard EM, Löw C, Moberg P, Trésaugues L, Nordlund P. Structural basis for substrate transport in the GLUT-homology family of monosaccharide transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:766–768. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun L, Zeng X, Yan C, Sun X, Gong X, Rao Y, Yan N. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of glucose transporters GLUT1-4. Nature. 2012;490:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature11524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cunningham P, Naftalin RJ. Reptation-induced coalescence of tunnels and cavities in Escherichia Coli XylE transporter conformers accounts for facilitated diffusion. J Membr Biol. 2014;247:1161–1179. doi: 10.1007/s00232-014-9711-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunningham P, Naftalin RJ. Implications of aberrant temperature-sensitive glucose transport via the glucose transporter deficiency mutant (GLUT1DS) T295M for the alternate-access and fixed-site transport models. J Membr Biol. 2013;246:495–511. doi: 10.1007/s00232-013-9564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topham CM, Brocklehurst K. In defence of the general validity of the Cha method of deriving rate equations. The importance of explicit recognition of the thermodynamic box in enzyme kinetics. Biochem J. 1992;282:261–265. doi: 10.1042/bj2820261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha S. A simple method for derivation of rate equations for enzyme-catalyzed reactions under the rapid equilibrium assumption or combined assumptions of equilibrium and steady state. J Biol Chem. 1968;243:820–825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carruthers A, Helgerson A. Inhibitions of sugar transport produced by ligands binding at opposite sides of the membrane. Evidence for simultaneous occupation of the carrier by maltose and cytochalasin B. Biochemistry. 1991;30:3907–3915. doi: 10.1021/bi00230a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helgerson AL, Carruthers A. Equilibrium ligand binding to the human erythrocyte sugar transporter. Evidence for two sugar-binding sites per carrier. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5464–5475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorga FR, Lienhard GE. Equilibria and kinetics of ligand binding to the human erythrocyte glucose transporter. Evidence for an alternating conformation model for transport. Biochemistry. 1981;20:5108–5113. doi: 10.1021/bi00521a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stein WD. Transport and diffusion across cell membranes. Academic Press; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carruthers A. Facilitated diffusion of glucose. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:1135–1176. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldwin SA, Baldwin JM, Lienhard GE. Monosaccharide transporter of the human erythrocyte. Characterization of an improved preparation. Biochemistry. 1982;21:3836–3842. doi: 10.1021/bi00259a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naftalin RJ, Holman GD. In: Membrane transport in red cells. Ellory JC, Lew VL, editors. Academic Press; New York: 1977. pp. 257–300. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cura AJ, Carruthers A. Role of Monosaccharide Transport Proteins in Carbohydrate Assimilation, Distribution, Metabolism, and Homeostasis. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012;2:863–91439. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carruthers A, De Zutter J, Ganguly A, Devaskar SU. Will the Original Glucose Transporter Isoform Please Stand Up! Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E836–8489. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00496.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zottola RJ, Cloherty EK, Coderre PE, Hansen A, Hebert DN, Carruthers A. Glucose transporter function is controlled by transporter oligomeric structure. A single, intramolecular disulfide promotes GLUT1 tetramerization. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9734–9747. doi: 10.1021/bi00030a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hebert DN, Carruthers A. Glucose transporter oligomeric structure determines transporter function. Reversible redox-dependent interconversions of tetrameric and dimeric GLUT1. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23829–23838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vollers S, Carruthers A. Sequence Determinants of GLUT1-mediated Accelerated-Exchange Transport - Analysis by Homology-Scanning Mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42533–42544. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.369587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krupka RM, Devés R. An experimental test for cyclic versus linear transport models. The mechanisms of glucose and choline transport in erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:5410–5416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blodgett DM, Carruthers A. Quench-Flow Analysis Reveals Multiple Phases of GluT1-Mediated Sugar Transport. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2650–2660. doi: 10.1021/bi048247m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helgerson AL, Carruthers A. Analysis of protein-mediated 3-O-methylglucose transport in rat erythrocytes: rejection of the alternating conformation carrier model for sugar transport. Biochemistry. 1989;28:4580–4594. doi: 10.1021/bi00437a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blodgett DM, De Zutter JK, Levine KB, Karim P, Carruthers A. Structural Basis of GLUT1 Inhibition by Cytoplasmic ATP. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:157–168. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heard KS, Fidyk N, Carruthers A. ATP-dependent substrate occlusion by the human erythrocyte sugar transporter. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3005–3014. doi: 10.1021/bi991931u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carruthers A, Helgerson AL. The human erythrocyte sugar transporter is also a nucleotide binding protein. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8337–8346. doi: 10.1021/bi00447a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Afzal I, Browning JA, Drew C, Ellory JC, Naftalin RJ, Wilkins RJ. Effects of anti-GLUT antibodies on glucose transport into human erythrocyte ghosts. Bioelectrochemistry. 2004;62:195. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Afzal I, Cunningham P, Naftalin RJ. Interactions of ATP, oestradiol, genistein and the anti-oestrogens, faslodex (ICI 182780) and tamoxifen, with the human erythrocyte glucose transporter, GLUT1. Biochem J. 2002;365:707–719. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sage JM, Cura AJ, Lloyd KP, Carruthers A. Caffeine inhibits glucose transport by binding at the GLUT1 nucleotide-binding site. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2015;308:C827–C834. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00001.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Zutter JK, Levine KB, Deng D, Carruthers A. Sequence determinants of GLUT1 oligomerization: analysis by homology-scanning mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20734–20744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.469023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kapoor K, Finer-Moore JS, Pedersen BP, Caboni L, Waight A, Hillig RC, Bringmann P, Heisler I, Müller T, Siebeneicher H, Stroud RM. Mechanism of inhibition of human glucose transporter GLUT1 is conserved between cytochalasin B and phenylalanine amides. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:4711–4716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603735113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colquhoun D, Dowsland KA, Beato M, Plested AJ. How to impose microscopic reversibility in complex reaction mechanisms. Biophys J. 2004;86:3510–3518. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.038679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]