Abstract

Tellurite (TeO32−) is a hazardous and toxic oxyanion for living organisms. However, several microorganisms can bioconvert TeO32− into the less toxic form of elemental tellurium (Te0). Here, Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 resting (non-growing) cells showed the proficiency to produce tellurium-based nanoparticles (NPs) and nanorods (NRs) through the bioconversion of TeO32−, depending on the oxyanion initial concentration and time of cellular incubation. Te-nanostructures initially appeared in the cytoplasm of BCP1 cells as spherical NPs, which, as the exposure time increased, were converted into NRs. This observation suggested the existence of an intracellular mechanism of TeNRs assembly and growth that resembled the chemical surfactant-assisted process for NRs synthesis. The TeNRs produced by the BCP1 strain showed an average length (>700 nm) almost doubled compared to those observed in other studies. Further, the biogenic TeNRs displayed a regular single-crystalline structure typically obtained for those chemically synthesized. The chemical-physical characterization of the biogenic TeNRs reflected their thermodynamic stability that is likely derived from amphiphilic biomolecules present in the organic layer surrounding the NRs. Finally, the biogenic TeNRs extract showed good electrical conductivity. Thus, these findings support the suitability of this strain as eco-friendly biocatalyst to produce high quality tellurium-based nanomaterials exploitable for technological purposes.

Introduction

The chalcogen Tellurium (Te) is a natural rare element of the Earth crust1 that is defined as a metalloid due to its intermediate properties between metals and non-metals2. The anthropogenic misuse of Te-compounds in several areas of application (i.e., electronics, optics, production of batteries, petroleum refining and mining)1,3–5 has led to an increased presence of several forms of Te in the environment, namely: inorganic telluride (Te2), the oxyanions tellurite (TeO32−) and tellurate (TeO42-), and the organic dimethyl telluride (CH3TeCH3)6. Among these Te forms, TeO32− is recognized as a soluble and hazardous pollutant, which can be found highly concentrated in soils and waters near by waste discharge sites of manufacturing and processing facilities7. Although TeO32− exerts its toxicity at concentrations as low as 1 μg mL−1 (4 μM)5 towards both prokaryotes and eukaryotes6, over the past 30 years mainly anaerobic or facultative anaerobic bacteria were investigated for their ability to bioconvert TeO32− 1,8,9, while much less is known about the bioconversion potential of aerobic bacterial strains towards these oxyanions10–12. Regardless of the bacterial strain investigated, a common feature reported by several authors, is that TeO32− bioconverting bacteria produces black precipitates within and/or outside the cells13,14. Indeed, the early work of Morton and Anderson (1941) observed needle-like crystals within and outside Corynebacterium diphtheriae cells grown on Chocolate Tellurite agar13, while Tucker and colleagues (1962) reported X-Ray diffraction analysis of Te crystalline nature of the black precipitates produced by Streptococcus fecalis N8311. Recently, these Te-crystals were recognized as nanosized structures generated by microorganisms as product of metal(loid) bioconversion8,15,16, which can be exploited to develop eco-friendly and cost-effective methods to synthesize valuable metalloid nanomaterials17. Indeed, the advantage of a microbial approach as compared to a synthetic procedure would be the abandonment of toxic chemicals, avoiding the formation of hazardous waste, and the use of extreme system conditions (i.e., high pressure and temperature), which determine the emergence of safety concerns17.

In this regard, among the strictly aerobic bacterial strains suitable as cell factories for nanotechnology purposes, those belonging to the Rhodococcus genus have been investigated due to their environmental robustness and persistence18, with the characteristic of resisting harsh growth conditions19,20. In a previous study, we reported the ability of Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 to cope with high concentrations of TeO32−, as well as its proficiency to bioconvert these oxyanions into the less toxic Te0, generating thermodynamically stable nanostructures21. Here, based on our prior findings, we further explored the strain BCP1 under metabolically active, yet resting (non-growing) cells. Conditions using these cells were optimized for the biotic conversion of TeO32− and to enhance the chemical-physical characteristics of the biogenic Te-nanomaterial produced. We investigated key parameters such as size, shape, and crystalline nature of the Te-nanostructures biosynthesized by BCP1, and we provided evidence for the presence of amphiphilic biomolecules in the organic layer surrounding the biogenic TeNRs, which might play a crucial role directing their growth and stabilizing them. Hence, we proposed a mechanism of assembly, growth and formation of the intracellularly generated TeNRs, whose electrical properties were evaluated as proof-of-concept of the suitability of this nanomaterial for future electronic applications.

Results and Discussion

BCP1’s tolerance and biotic conversion of TeO32−

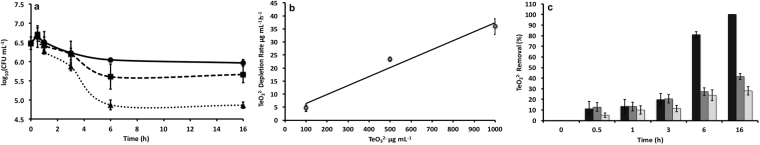

The exploitation of bacteria bioconverting chalcogen oxyanions22 is now recognized as a valuable approach to develop green-synthesis strategies to produce unique nanoscale materials23. In our previous study, the capability of BCP1 cells grown aerobically in the presence of TeO32− to biosynthesize TeNRs as product of TeO32− bioconversion was observed21. In our research exploring different physiological conditions to optimize TeNRs production, we discovered that BCP1 resting cells had a greater performance to produce extremely long TeNRs as compared to actively growing cultures21. Indeed, although TeO32− exposure caused a certain level of cell death directly proportional to the initial concentration of oxyanions (Fig. 1(a)), 100 μg mL−1 of TeO32− was bioconverted 20 h faster by BCP1 resting cells (Fig. 1(c)) as compared to the actively growing culture21. Similar conclusions can be drawn in the case of BCP1 resting cells exposed to 500 μg mL−1 of TeO32−, even though 16 h exposure did not lead to 100% bioconversion (42 ± 3% removal). BCP1’s tolerance towards this oxyanion was further highlighted by its capability to remove 28 ± 4% (corresponding to 280 ± 40 μg mL−1) when exposed to 1000 μg mL−1 TeO32− over 16 h (Fig. 1(c)). In comparison, Escherichia coli K12 strain showed a similar TeO32− bioconversion trend but under anoxic conditions in the presence of the quinone electron carrier analogue lawsone24. The highly resistant Gram-positive aerobic bacteria Bacillus sp. BZ and Salinicoccus sp. QW6 did not bioconvert more than 100 or 125 μg mL−1 of TeO32− within 50 or 72 h exposure, respectively10,12. In our study, TeO32− removal rate was calculated after 3 h of cellular exposure to the oxyanions, as a comparable extent of live cells was detected for each experimental condition, and a linear correlation of TeO32− removal rate as function of the initial oxyanion concentration was observed, being the measured rates of 4.6 ± 1.3 μg mL−1 h−1 (100 μg mL−1), 23.4 ± 0.7 μg mL−1 h−1 (500 μg mL−1) and 36 ± 3.0 μg mL−1 h−1 (1000 μg mL−1) (Fig. 1(b)). Finally, no abiotic TeO32− removal was observed over the timeframe tested, as shown in the Supplementary Fig. S1.

Figure 1.

Survival curve, initial TeO32− depletion rate and percentage of TeO32− removal. (a) Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 resting cells survival curve upon increased initial concentration of TeO32−, being 100 ( ), 500 (

), 500 ( ) or 1000 (

) or 1000 ( ) μg mL−1, while in (b) is shown the initial depletion rate (

) μg mL−1, while in (b) is shown the initial depletion rate ( ) of TeO32−. The linear correlation (

) of TeO32−. The linear correlation ( ) that fits the experimental data points gave an R2 = 0.97. In (c) is reported the percentage of TeO32− removal over the considered timeframe for each initial oxyanion concentration [100 (■), 500 (

) that fits the experimental data points gave an R2 = 0.97. In (c) is reported the percentage of TeO32− removal over the considered timeframe for each initial oxyanion concentration [100 (■), 500 ( ) or 1000 (

) or 1000 ( ) μg mL−1]. The error bars indicate the standard deviation of three biological replicates.

) μg mL−1]. The error bars indicate the standard deviation of three biological replicates.

Electron microscopy characterization of the biogenic Te-nanomaterials

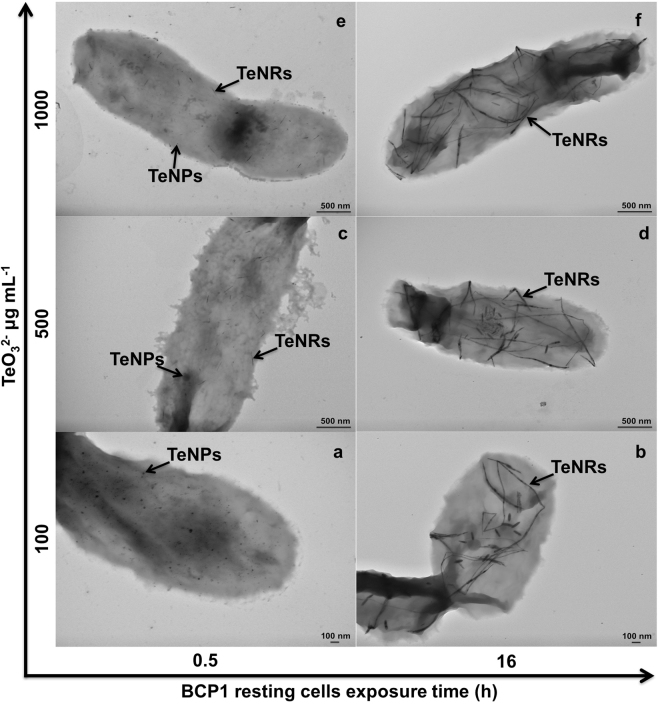

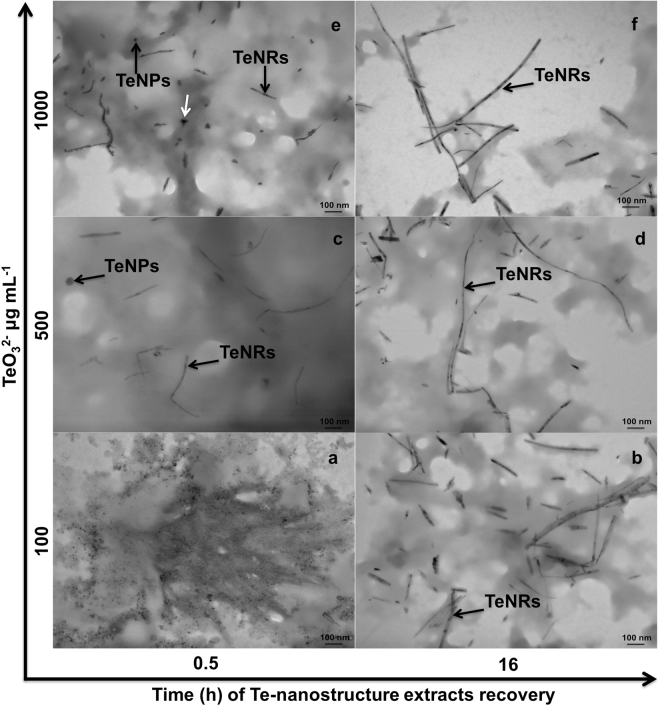

BCP1’s remarkable potential in removing TeO32− was coupled to its proficiency to generate intracellular Te-nanostructures in the form of NPs and NRs in all experimental conditions tested (Fig. 2; Supplementary Figs S2, S3 and S4). To date, several other Gram-positive bacterial strains were recently described for their capability to generate Te-nanomaterials in the form of NRs, even if these mostly appeared either as needle-like structures or intra-/extra-cellular rosettes constituted by clustered NRs8,25. Conversely, the production of not aggregated intracellular TeNRs was only observed in the case of Bacillus sp. BZ12, BCP1 growing21 and resting cells (Fig. 2). Remarkably, TeNRs within the extracts recovered from BCP1 cells either grown21 or exposed to TeO32− still maintained their strong thermodynamic stability, even after mounting and air-drying on a carbon-coated copper grid for TEM imaging (Fig. 3; Supplementary Figs S5, S6 and S7).

Figure 2.

Imaging of the BCP1 strain by electron microscopy. Transmission Electron Microscopy observations of Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 resting cells exposed to different concentrations (100, 500 and 1000 μg mL−1) of TeO32− either for 0.5 (a,c and e) or 16 h (b,d and f); TeNPs and TeNRs within the cells are indicated by black arrows.

Figure 3.

Imaging of TeNRs extracts recovered from BCP1 cells. Transmission Electron micrographs of Te-nanostructure extracts recovered after 0.5 (a,c and e) or 16 h (b,d and f) exposure of the BCP1 strain to 100, 500 and 1000 μg mL−1 of TeO32−; spherical and rod-shaped Te-nanostructures, as well as shard-like NPs are indicated by black and white arrows, respectively.

Under resting cell experimental conditions, the BCP1 strain exposed to the lowest TeO32− concentration (100 μg mL−1) produced primarily TeNPs (Fig. 2(a)) at the earliest stage of incubation (0.5 h), while at higher initial TeO32− concentrations (i.e., 500 and 1000 μg mL−1) both TeNPs and TeNRs were detected within the cells (Fig. 2(c,e)). TeNPs were still observed up to 1 h after initial cellular exposure to each concentration of TeO32− precursor (Supplementary Figs S2b, S3b and S4b); while the production of Te-nanomaterials shifted towards 1D morphology (TeNRs) when BCP1 cells were incubated with TeO32− for more than 3 h (Figs 2(b,d,f)); Supplementary Fig. S2, S3 and S4). Furthermore, TEM micrographs of Te-nanostructure extracts recovered from BCP1 resting cells exposed for 0.5 h to 100 μg mL−1 of TeO32− displayed the presence of undefined electron-dense nanomaterials resembling mesoparticles (Fig. 3(a)), while defined TeNPs and TeNRs (Fig. 3(c,e) were observed as the concentration of TeO32− precursor increased (500 and 1000 μg mL−1). Shard-like NPs were also detected along with TeNRs within Te-nanostructure extracts isolated from BCP1 cells exposed for either 0.5 or 1 h to 1000 μg mL−1 of TeO32− (indicated by white arrows in Fig. 3(e)); Supplementary Fig. S7a,b). Although different morphologies of Te-nanostructures were detected, the biosynthesis was tuned towards TeNRs as the main nanomaterial product under all the experimental conditions tested (Supplementary Figs S5, S6 and S7).

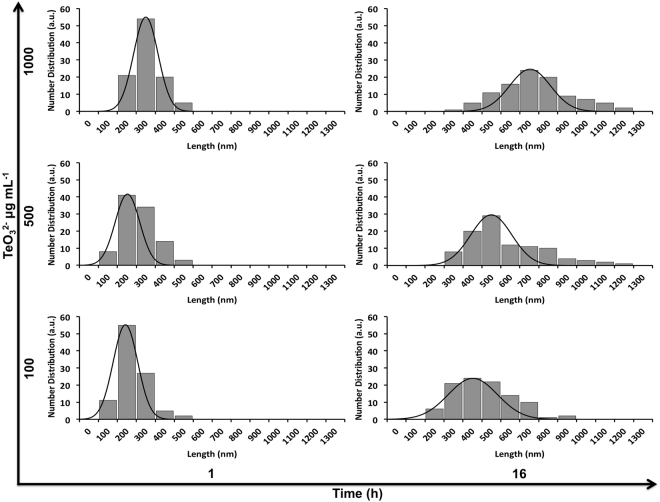

The measurement of the average length and diameter of TeNRs was evaluated as function of both TeO32− exposure time and initial concentration (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. S8 and Tables S1 and S2). TeNRs were polydisperse in size with an average length shifting from short to very long NRs as the cellular exposure time and the initial TeO32− concentration increased (Supplementary Fig. S8 and Table S1). On the other hand, none of these experimental conditions influenced the measured TeNRs average diameter (Supplementary Table S2). Indeed, the growth of the nanomaterials was primarily maintained in 1D, producing very long NRs or ribbon-like structures, instead of branched nanomorphologies. The remarkable potential of BCP1 as biofactory to produce unique TeNRs is further highlighted comparing their average length (781 ± 189 nm) with that produced by actively growing cells (463 ± 147 nm)21 or other bacterial strains, such as Rhodobacter capsulatus (369 ± 131 nm)8, Bacillus selenitireducens (200 nm)25 and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 (100–200 nm)15.

Figure 4.

Length distribution of biogenic TeNRs. Length distribution ( ) of TeNRs generated by Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 resting cells exposed for either 1 or 16 h to 100, 500 and 1000 μg mL−1 of TeO32−. The Gaussian fit is indicated by (

) of TeNRs generated by Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 resting cells exposed for either 1 or 16 h to 100, 500 and 1000 μg mL−1 of TeO32−. The Gaussian fit is indicated by ( ).

).

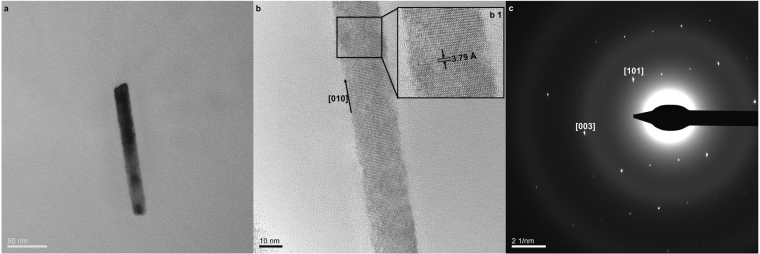

Te0 tendency to form 1D nanostructures relies on the high thermodynamic stability of trigonal tellurium (t-Te), which is responsible for the anisotropic growth of Te-nanocrystallinities along one axis26. In this respect, the biogenic TeNRs generated byBCP1 were analyzed through HR-TEM imaging and SAED and revealed individual and regular NRs without any defects or dislocations along the longitudinal c-axis, indicating their uniform and single-crystalline structure (Fig. 5(b,c)). The electron diffraction (ED) patterns collected from different regions of a single TeNR confirmed the unique nature of this biogenic nanomaterial, which resembled that chemically synthesized27. The periodic fringe spacing of ca. 3.79 Å (Fig. 5(b)) was consistent with the established interplanar distance of ca. 3.90 Å for the separation between the [010] lattice planes of t-Te [space group P3121(152)]27. Further, the TeNR ED pattern was indexed as pure t-Te phase with calculated lattice constants a = 4.38 Å and c = 5.83 Å (Fig. 5(c)), whose values are in line with those reported in the literature (a = 4.45 Å; c = 5.92 Å; JCPDS 36-1452).

Figure 5.

High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy. (a) Bright-field electron micrograph of a single TeNR; (b) High-Resolution micrograph that highlights the [010] growth plane of TeNR crystal. The enlarged insert (b1) displays the interplanar distance of the periodic fringe spacing, while (c) shows the corresponding electron diffraction pattern in which the diffraction spots [101] and [003] are indexed.

Mechanism of assembly and growth of the biogenic TeNRs

The nanomorphological change observed for the biogenic nanomaterial indicated a specific mechanism of assembly and growth of the NRs within BCP1 cells exposed to TeO32−. According to the established chemical models of TeNRs synthesis26–29, the formation of 1D nanostructures is preceded by the generation of NPs generally featured by Te in amorphous state (a-Te), conferring them a high surface energy and hence thermodynamic instability. Thus, TeNPs rapidly dissolve and the available Te0 atoms organize themselves depositing as t-Te in one direction forming NRs through a ripening process30,31. The kinetics of this event is directly dependent on the concentration of TeO32− precursor supplied, resulting in a faster dissolution of TeNPs as the initial amount of oxyanion increased30,31. The entire process resulted to be emphasized in BCP1, as the biotic conversion of TeO32− occurred in the cytoplasm, leading to a large number of Te0 atoms confined in the small cellular volume and available to produce TeNRs. Indeed, considering that the bioconversion rate of TeO32− increased as function of the initial oxyanion concentration (Fig. 1(b)), BCP1 cells exposed for 0.5 h to 100 μg mL−1 of TeO32− produced only TeNPs (Fig. 2(a)), while at higher oxyanion concentrations (either 500 or 1000 μg mL−1) they generated both TeNPs and TeNRs at this early time point (Fig. 2(c,e)).

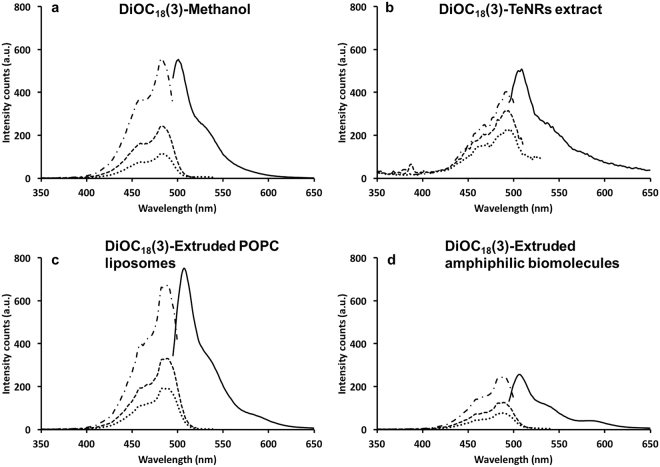

Chemical synthesis of TeNRs is mostly reliant on the addition to the reaction system of surfactant molecules32–34 that adsorb onto the TeNP surface limiting their aggregation31. Once the transition from a-Te to t-Te takes place, the formation of single-crystalline NRs is driven by the surfactant molecules that strongly interact with Te0 atoms, confining the growth of TeNRs along one axis without affecting their diameter30,31,35,36. Since little variation in the diameter of the biogenic TeNRs was detected (Supplementary Table S2), this observation indicated that amphiphilic biomolecules supplied by the BCP1 cells acting as surfactants could mediate the growth of NRs along one axis. To evaluate this, the existence of amphiphilic molecules within the aqueous TeNRs extract was here assessed exploiting the lipophilic tracer DiOC18(3) capable of specifically binding to the hydrophobic moieties of amphiphilic molecules in the extract, leading to a change in fluorescence37, as the unbound tracer molecules are quenched in water38. Indeed, a fluorescent emission peak at 507 nm was detected for the TeNRs extract (DiOC18(3)-TeNRs extract), which was comparable to that of the lipophilic tracer dissolved in methanol (DiOC18(3)-methanol; 501 nm) (Fig. 6(a,b)). These results were confirmed by the excitation spectra, which showed the same peaks for DiOC18(3)-TeNRs extract and DiOC18(3)-methanol (Fig. 6(a,b)). To understand whether the amphiphilic biomolecules detected within the TeNRs extract could chemically resemble surfactants, these macromolecules were isolated and extruded and their behaviour was compared to that of extruded POPC liposomes. Firstly, DLS analyses revealed similar size distributions of the POPC liposomes (105 ± 4.7 nm; PdI = 0.146) and the amphiphilic biomolecules (105 ± 6.4 nm; PdI = 0.166) (Supplementary Fig. S9), indicating their capability to auto-assemble at the nanoscale in aqueous solution. Moreover, the amphiphilic biomolecules and POPC liposomes labelled with DiOC18(3) showed emission and excitation fluorescence peaks at the same wavelengths compared to those of DiOC18(3)-TeNRs extract (Fig. 6c and d). Additionally, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) was performed to evaluate variations in the diffusion times and coefficients of the lipophilic tracer when it was added to (i) TeNRs extract, (ii) POPC liposomes, and (iii) the isolated amphiphilic biomolecules (Table 1). These results showed a higher diffusion coefficient of DiOC18(3)-methanol as compared to those obtained for both DiOC18(3)-TeNRs extract and DiOC18(3)-extruded amphiphilic biomolecules, which were similar to that of DiOC18(3)-extruded POPC liposomes (Table 1).

Figure 6.

Fluorescence excitation and emission spectra. The Lipophilic tracer DiOC18(3) was utilized to collect the emission ( λ 484 nm) and excitation (

λ 484 nm) and excitation ( λ 500 nm;

λ 500 nm;  λ 530 nm; ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ λ 550 nm) fluorescent spectra when it was dissolved in methanol (a), in association with the biogenic TeNRs extract (b) or extruded POPC liposomes (c) or the isolated and extruded amphiphilic molecules (d).

λ 530 nm; ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ λ 550 nm) fluorescent spectra when it was dissolved in methanol (a), in association with the biogenic TeNRs extract (b) or extruded POPC liposomes (c) or the isolated and extruded amphiphilic molecules (d).

Table 1.

DiOC18(3) diffusion times and coefficients evaluated by FCS.

| Samples | Diffusion coefficient (μm2 s−1) | Diffusion time (ms) |

|---|---|---|

| DiOC18(3)-methanol | 345 ± 50 | 0.22 ± 0.08 |

| DiOC18(3)-extruded amphiphilic biomolecules | 4.78 ± 1.37 | 15.7 ± 1.62 |

| DiOC18(3)-extruded POPC liposomes | 4.20 ± 1.11 | 17.9 ± 2.42 |

| DiOC18(3)-TeNRs extract | 3.79 ± 1.86 | 19.8 ± 3.47 |

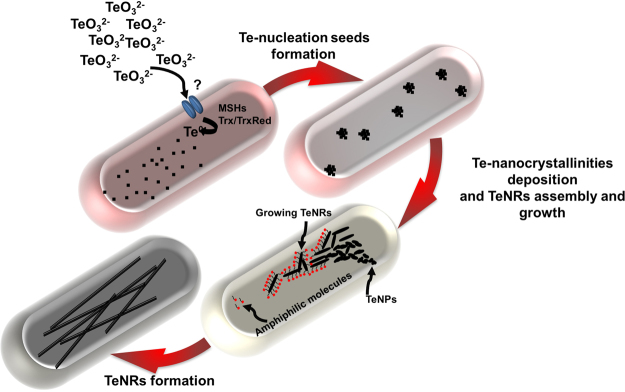

Thus, the fluorescence spectra and the FCS analyses strongly suggested that the amphiphilic biomolecules present within the aqueous biogenic TeNRs extract behaved as non-ionic surfactants (POPC), which have been previously utilized as driving force and stabilizers for chemically synthesized NRs39,40. Based on these evidences, a mechanism explaining the assembly and growth of TeNRs occurring within BCP1 resting cells is proposed in Fig. 7.

Figure 7.

Intracellular assembly and growth of biogenic TeNRs. Once internalized by BCP1 cells, TeO32− bioconversion leads to the formation of Te0 atoms, whose concentration increases as the BCP1 exposure time to the oxyanions increases. Over the incubation time, Te0 atoms reach such a critical intracellular concentration that determines their aggregation, counteracting their thermodynamic instability within the cellular environment. This event results in the formation of Te nucleation seeds, whose intracellular concentration increases the more is the extent of TeO32− bioconversion. Te-seeds then collapse each other forming TeNPs featured by a-Te, which is less thermodynamic stable compared to t-Te. In this respect, biogenic TeNPs tend to dissolve providing Te0 atoms that deposit as t-Te nanocrystallinities, which then grow intracellularly along one axis forming TeNRs, whose growth process might be assisted by the amphiphilic molecules co-produced by the BCP1 strain.

Electrical conductivity of the biogenic TeNRs extract

Since Te is a well-known narrow band-gap p-type semiconductor41, it exhibits high photoconductivity, piezoelectricity, thermoelectricity and non-linear optical response properties42,43, allowing the use of Te-based nanomaterials as optoelectronic, thermoelectric, piezoelectric devices, as well as gas sensors and infrared detectors44–48. Thus, we explored the conductive properties of the biogenic TeNRs extract, measuring its resistance (R) through the Four Probe technique49. The biogenic TeNRs extract air dried on the silicon support gave a low resistance value (R = 8 ± 1 Ω), compared to that of the silicon chip itself (R = 281 ± 7 Ω), and the isolated amphiphilic molecules (R = 145 ± 2 Ω). These values corresponded to an electrical conductivity (σ) of 3.0 ± 0.5, 0.08 ± 0.002 and 0.16 ± 0.02S m−1, respectively. Hence, TeNRs within the extract were shown to be electrically conductive, approaching the electrical conductivity values of those chemically synthesized, with σ ranging between 8 and 10S m−1 50,51.

Conclusions

The present study highlights the capability of the strictly aerobic Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 strain to tolerate very high concentrations of the toxic oxyanion TeO32− under the physiological state of resting cells as compared to those actively growing21. Although the biotic conversion of TeO32− led to the intracellular production of different tellurium nanomaterial morphologies at early time points, the main nanostructure biosynthesized was TeNRs, whose average length was impressively long as compared to TeNRs reported in the literature so far. Moreover, the biogenic TeNRs showed a single-crystalline structure resembling those chemically synthesized, while the morphological changes of biogenic Te-nanostructures and the unchanged average diameter of the TeNRs suggested a specific mechanism of their assembly and confined growth within BCP1 cells, which might be assisted by the co-produced amphiphilic biomolecules from this Rhodococcus strain. Finally, the biogenic TeNRs extract showed to be electrically conductive, approaching those chemically produced and, therefore, underlining the suitability of this strain as an eco-friendly cell factory exploitable to synthesize valuable Te-based nanomaterials for future technological uses.

Methods

Bacterial strain and exposure conditions

Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 strain (DSM 44980) was cultured as described elsewhere21, whose details are indicated in the Supplementary Information. The number of viable cells is reported as average of the Colony Forming Unit (log10[CFU mL−1]) for each biological trial (n = 3) with standard deviation (SD). All the reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich®.

TeO32− removal assay

The extent of TeO32− removal by BCP1 resting cells during the exposure timeframe was estimated as published elsewhere52 and described in detail in the Supplementary Information. The data are reported as average (n = 3) of the percentage value corresponding to TeO32− removal over the incubation time with SD. Further, since any statistical difference was observed between the CFU mL−1 counted at the earliest stages of BCP1 resting cells incubation to each oxyanion concentration tested, the specific rate of TeO32− bioconversion (expressed as μg mL−1 h−1) was calculated using a linear regression of the data collected over 3 h.

Recovery of Te-nanostructure extracts and electron microscopy imaging

Te-nanostructure extracts were recovered from BCP1 resting cells following the procedure published in our previous study21, while Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) imaging of both TeO32−-exposed BCP1 resting cells and Te-nanostructure extracts was performed using a Hitachi H7650 TEM. For bright field (BF) and high-resolution (HR) TEM, as well as the corresponding Selected-Area Electron Diffraction (SAED) pattern of TeNRs were collected by FEI Tecnai F20 TEM at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The samples were prepared by mounting 5 µL of either cellular suspensions or Te-nanostructure extracts on carbon-coated copper grids (CF300-CU, Electron Microscopy Sciences), which were air-dried prior the imaging. TEM micrographs were analyzed through ImageJ software to measure the actual length of TeNRs, which was calculated considering 100 randomly chosen nanorods. The distribution was fitted to a Gaussian function to yield the average length of TeNRs.

Sample preparation

For experiments aimed to evaluate the presence of amphiphilic biomolecules within the TeNRs extract, the sample containing the amphiphilic biomolecules without biogenic nanomaterial was isolated as described elsewhere21. As a control experiments, a liposome solution (5 mM) was prepared by dissolving in 5 mL of water 19 mg of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) (Avanti® Polar Lipids, Inc), which is non-ionic surfactant53. The POPC liposome solution and the isolated amphiphilic biomolecules were extruded through a Mini-Extruder equipped with a polycarbonate membrane (0.1 μm) (Avanti® Polar Lipids, Inc).

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

DLS measurements were performed onto 1 mL of (i) the isolated and extruded amphiphilic biomolecules and (ii) the POPC liposome solution by using Zen 3600 Zetasizer Nano ZS™ from Malvern Instruments.

Fluorescence spectroscopy and Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) analyses

The lipophilic tracer 3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine perchlorate (DiOC18(3) Invitrogen™) dissolved in methanol was used as the probe in all experiments. 3 mL of DiOC18(3) stock solution (0.4 mM) was utilized to obtain fluorescence spectra of the free dye. TeNRs extract, as well as the isolated and extruded amphiphilic molecules were incubated with the dye previously dried under argon flow, incubating 3 mL of each sample for 30 minutes at room temperature with shaking. Further, the POPC liposome solution was dried along with the dye under argon flow, then resuspended in 3 mL of water to incorporate the lipophilic tracer within the liposomes. The samples were excited (λex) at 488 nm and fluorescence emission spectra were collected above 495 nm wavelength using a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorescence spectrophotometer, while excitation spectra were obtained for 3 different fixed wavelengths (λfix; 510, 530 and 550 nm).

FCS experiments were carried out with an ISS Alba IV Confocal Spectroscopy & Imaging Workstation coupled with a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U microscope. The lipophilic tracer was diluted to a final concentration of 2 nM, and 400 μl of this dilution was used to perform FCS. The autocorrelation curves corresponding to all the samples were obtained from 15 independent runs by exiting the dye with a single photon CW Ar-laser (λex = 488 nm). All the autocorrelation functions were built by the Vistavision ISS software and fitted according to a theoretical model for three-dimensional (3D) global diffusion, assuming that the detection volume was approximated by a 3D Gaussian function54. Based on the fitted autocorrelation functions, for each sample the diffusion coefficient and the time of diffusion were calculated.

Four Probe technique

The electrical property of the TeNRs extract was studied by air drying 800 μL of sample onto a 2 × 1 cm Crystal Silicon wafer (type N/Phos, size 100 mm, University Wafer), whose contacts were drawn through silver painting (PELCO® TED PELLA, INC.) to enhance the resistance values recorder by 5492B Digit Multimeter (BK PRECISION®). The obtained resistance values correspond to the average of 6 independent measurements with SD.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) is gratefully acknowledged for the support of this study. We also acknowledge the Nanoscience Program at the University of Calgary for providing access to FCS and Four-Probe Multimeter, and Microscopy Imaging Facility (MIF) at the University of Calgary for providing access to TEM.

Author Contributions

The Post-doctoral fellow A.P. and the PhD student E.P. of the Microbial Biochemistry Laboratory at the Department of Biological Sciences of the Calgary University, contributed to the scientific development of this study, namely: (i) performing of the experiments, (ii) data interpretation, (iii) major contribution to the writing of the manuscript. A.D., staff scientist at the Microscopy and Imaging Facility (MIF) of the University of Calgary, collected the bright field and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy images, as well as the electron-diffraction patterns of the biogenic produced Te-nanostructures along with their interpretation. M.A., instructor at the Chemistry Department of the University of Calgary, carried out the characterization of the biogenic Te-nanostructures by Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy along with the interpretation of the data and editing of the physical-chemical part of the manuscript. M.C., research associate in the Laboratory of General and Applied Microbiology at the Department of Pharmacy and Biotechnology of the University of Bologna, participated in the revision of the manuscript giving important suggestions for a better interpretation of the biological results. D.Z., full professor and coordinator of the Laboratory of General and Applied Microbiology at the Department of Pharmacy and Biotechnology of the University of Bologna, provided us the Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 strain and intellectually contributed to the interpretation and development of this study. R.J.T., full professor and coordinator of the Microbial Biochemistry Laboratory at the Department of Biological Sciences of the University of Calgary, had a major intellectual and financial contribution during the development of this study, managing and directing the research as well as editing and revising the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-22320-x.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alessandro Presentato, Email: alessandro.presentat@ucalgary.ca.

Raymond J. Turner, Email: turnerr@ucalgary.ca

References

- 1.Di Tommaso G, et al. The membrane-bound respiratory chain of Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes KF707 cells grown in the presence or absence of potassium tellurite. Microbiology. 2002;148:1699–1708. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haynes, W. M. Section 4: properties of the elements and inorganic compounds. In CRC Handbook of chemistry and physics, 95th ed. (ed, Haynes W. M.) 115–120 (CRC Press/Taylor and Francis, 2014).

- 3.Tang Z, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Glotzer SC, Kotov NA. Self-assembly of CdTe nanocrystals into free-floating sheets. Science. 2006;314:274–278. doi: 10.1126/science.1128045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Graf C, Assoud A, Mayeasree O, Kleinke H. Solid state polyselenides and polytellurides: a large variety of Se-Se and Te-Te interactions. Molecules. 2009;14:15–31. doi: 10.3390/molecules14093115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor DE. Bacterial tellurite resistance. Trends. Microbiol. 1999;7:111–115. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(99)01454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner RJ. Tellurite toxicity and resistance in Gram-negative bacteria. Rec. Res. Dev. Microbiol. 2001;5:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrison JJ, Ceri H, Stremick CA, Turner RJ. Biofilm susceptibility to metal toxicity. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;6:1220–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borghese R, et al. Extracellular Production of Tellurium Nanoparticles by the Photosynthetic Bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016;309:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klonowska A, Heulin T, Vermeglio A. Selenite and Tellurite Reduction by Shewanella oneidensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:5607–5609. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5607-5609.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amoozegar MA, et al. Isolation and initial characterization of the tellurite reducing moderately halophilic bacterium, Salinicoccus sp. strain QW6. Microbiol. Res. 2008;163:456–465. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tucker FL, Thomas JW, Appleman MD, Donohue J. Complete reduction of tellurite to pure tellurium metal by microorganisms. J. Bacteriol. 1962;83:1313–1314. doi: 10.1128/jb.83.6.1313-1314.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zare B, et al. Biosynthesis and recovery of rod-shaped tellurium nanoparticles and their bactericidal activities. Mat. Res. Bull. 2012;47:3719–3725. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2012.06.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morton HE, Anderson TF. Electron microscopic studies of biological reactions. I. Reduction of potassium tellurite by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Proc. Soc. Exptl. Biol. Med. 1941;46:272–276. doi: 10.3181/00379727-46-11963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Terai T, Kamahora Y, Yamamura Y. Tellurite reductase from Mycobacterium avium. J. Bacteriol. 1958;75:535–539. doi: 10.1128/jb.75.5.535-539.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DH, Kanaly RA, Hur HG. Biological accumulation of tellurium nanorod structures via reduction of tellurite by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Bioresour. Technol. 2012;125:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zonaro E, Lampis S, Turner RJ, Qazi SJS, Vallini G. Biogenic selenium and tellurium nanoparticles synthetized by environmental microbial isolates efficaciously inhibit bacterial planktonic cultures and biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:584. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ingale AG, Chaudhari AN. Biogenic Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Potential Applications: an EcoFriendly Approach. J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 2013;4:165. doi: 10.4172/2157-7439.1000165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínková L, Uhnáková B, Pátek M, Nesvera J, Kren V. Biodegradation potential of the genus Rhodococcus. Environ. Int. 2009;35:162–177. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cappelletti M, et al. Growth of Rhodococcus sp. strain BCP1 on gaseous n-alkanes: new metabolic insights and transcriptional analysis of two soluble di-iron monooxygenase genes. Front in Microbiol. 2015;6:393. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orro A, et al. Genome and Phenotype Microarray Analyses of Rhodococcus sp. BCP1 and Rhodococcus opacus R7: Genetic Determinants and Metabolic Abilities with Environmental Relevance. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Presentato A, et al. Rhodococcus aetherivorans BCP1 as Cell Factory for the Production of Intracellular Tellurium Nanorods under Aerobic Conditions. Micro. Cell Fact. 2016;15:204. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0602-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner RJ, Borghese R, Zannoni D. Microbial processing of tellurium as a tool in biotechnology. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012;30:954–963. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh P, Kim YJ, Zhang D, Yang DC. Biological Synthesis of Nanoparticles from Plants and Microorganisms. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34:588–599. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, et al. Quinone-mediated reduction of selenite and tellurite by Escherichia coli. Bioresour. Technol. 2011;102:3268–3271. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baesman SM, et al. Formation of tellurium nanocrystals during anaerobic growth of bacteria that use Te oxyanions as respiratory electron acceptors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:2135–2143. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02558-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mayers B, Xia Y. One-dimensional nanostructures of trigonal tellurium with various morphologies can be synthesized using a solution-phase approach. J. Mater. Chem. 2002;12:1875–1881. doi: 10.1039/b201058e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xi B, Xiong S, Fan H, Wang X, Qian Y. Shape-Controlled Synthesis of Tellurium 1D Nanostructures via a Novel Circular Transformation Mechanism. Cryst. Growth Des. 2007;7:1185–1191. doi: 10.1021/cg060663d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mo M, et al. Controlled Hydrothermal Synthesis of Thin Single-Crystal Tellurium Nanobelts and Nanotubes. Adv. Mater. 2002;14:1658–1662. doi: 10.1002/1521-4095(20021118)14:22<1658::AID-ADMA1658>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li XL, Cao GH, Feng CM, Li YD. Synthesis and magnetoresistance measurement of tellurium microtubes. J. Mater, Chem. 2004;14:244–247. doi: 10.1039/b309097c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gautam UK, Rao CNR. Controlled synthesis of crystalline tellurium nanorods, nanowires, nanobelts and related structures by a self-seeding solution process. J. Mater. Chem. 2004;14:2530–2535. doi: 10.1039/b405006a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Z, et al. Size-Controlled Synthesis and Growth Mechanism of Monodisperse Tellurium Nanorods by a Surfactant-Assisted Method. Langmiur. 2004;20:214–218. doi: 10.1021/la035160d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikoobakht B, El-Sayed MA. Preparation and Growth Mechanism of Gold Nanorods (NRs) Using Seed-Mediated Growth Method. Chem. Mater. 2003;15:1957–1962. doi: 10.1021/cm020732l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jana, N. R., Gearheart, L., Murphy, C. J. Wet chemical synthesis of silver nanorods and nanowires of controllable aspect ratio. Chem. Commun. 617–618 (2001).

- 34.Puntes VF, Krishnan KM, Alivisatos AP. Colloidal nanocrystal shape and size control: the case of cobalt. Science. 2001;291:2115–2117. doi: 10.1126/science.1057553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao GS, Zhang XJ, Su L, Ruan YY. Hydrothermal synthesis of selenium an tellurium nanorods. J. Exp. Nanosci. 2011;6:121–126. doi: 10.1080/17458081003774677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu, Y., Qian, Y. Chapter 7: Hydrothermal synthesis of Inorganic Nanomaterials. In Prescott, W. V., Schwartz, A. I., eds Nanorods, Nanotubes and Nanomaterials Research Progress. 279–304 (Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2008).

- 37.Yefimova SL, et al. Hydrophobicity effect of interaction between organic molecules in nanocages of surfactant micelle. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2008;75:658–663. doi: 10.1007/s10812-008-9108-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hauglang, R. P. Handbook of Fluorescent Probes and Research Products, 9th Ed. (Molecular Probes, 2002).

- 39.Orendorff CJ, Alam TM, Sasaki DY, Bunker BC, Voigt JA. Phospholipid-Gold Nanorod Composites. ACS Nano. 2009;3:971–983. doi: 10.1021/nn900037k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santhosh PB, Thomas N, Sudhakar S, Chadha A, Mani E. Phospholipid stabilized gold nanorods: towards improved colloidal stability and biocompatibility. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017;19:18494–18504. doi: 10.1039/C7CP03403B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Araki K, Tanaka T. Piezoelectric and Elastic Properties of Single Crystalline Se-Te Alloys. Appl. Phys. Expr. 1972;11:472–479. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tangney P, Fahy S. Density-functional theory approach to ultrafast laser excitation of semiconductors: Application to the A1 phonon in tellurium. Phys Rev B. 2002;14:279. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suchand Sandeep CS, Samal AK, Pradeep T, Philip R. Optical limiting properties of Te and Ag2Te nanowires. Chem. Phys Lett. 2010;485:326–330. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2009.12.065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sharma YC, Purohit A. Tellurium based thermoelectric materials: New directions and prospects. J. Integr. Sci. Technol. 2016;4:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Panahi-Kalamuei M, Mousavi-Kamazani M, Salavati-Niasari M. Facile Hydrothermal Synthesis of Tellurium Nanostructures for Solar Cells. JNS. 2014;4:459–465. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tsiulyanua D, Marian S, Miron V, Liess HD. High sensitive tellurium based NO2 gas sensor. Sens. Actuators B. 2001;73:35–39. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4005(00)00659-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baghchesara MA, Yousefi R, Cheraghizadec M, Jamali-Sheinid F, Saáedi A, Mahmmoudiane MR. A simple method to fabricate an NIR detector by PbTe nanowires in a large scale. Mater. Res. Bull. 2016;77:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.materresbull.2016.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang W, Wu H, Li X, Chen T. Facile One-Pot Synthesis of Tellurium Nanorods as Antioxidant and Anticancer Agents. Chem. Asian J. 2016;11:2301–2311. doi: 10.1002/asia.201600757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smits FM. Measurement of Sheet Resistivities with the Four-Point Probe. Bell Labs Tech. J. 1958;37:711–718. doi: 10.1002/j.1538-7305.1958.tb03883.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.See KC, et al. Water-Processable Polymer-Nanocrystal Hybrids for Thermoelectrics. Nano Lett. 2010;10:4664–4667. doi: 10.1021/nl102880k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yee SK, Coates NE, Majumdar A, Urban JJ, Segalman RA. Thermoelectric power factor optimization in PEDOT:PSS tellurium nanowire hybrid composites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013;15:4024–4032. doi: 10.1039/c3cp44558e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner RJ, Weiner JH, Taylor DE. Use of Diethyldithiocarbamate for Quantitative Determination of Tellurite Uptake by Bacteria. Anal. Biochem. 1992;204:292–295. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pohl H, Manzoor R, Morgner H. Adsorption behavior of the ternary system of phospholipid 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-gylycero-3-phosphocholine in 3-hydroxypropionitrile with added tetrabutyl ammonium bromide. Surf. Sci. 2013;618:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2013.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rigler R, Mets U, Widengren J, Kask P. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy with high count rate and low background: analysis of translational diffusion. Eur. Biophys. J. 1993;22:169–175. doi: 10.1007/BF00185777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).