Significance

Herbicide-resistant weeds are a major threat to the world’s food security and result in the loss of billions of dollars of income to crop producers. Penoxsulam, a member of the triazolopyrimidine family of commercial herbicides, has become a center of focus due to an increase in the number of weeds that have developed resistance to this compound. Thus, understanding its mode of action will assist in managing this problem. Here, our crystallographic data capture “in action” the molecular mechanisms that underpin how this herbicide operates. As well as having an effective binding affinity for acetohydroxyacid synthase, it is able to induce and enhance the production of peracetate, a highly reactive oxidant that induces the accumulative inhibition of its target.

Keywords: acetohydroxyacid synthase, crystal structure, FAD, herbicide, ThDP

Abstract

Acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS), the first enzyme in the branched amino acid biosynthesis pathway, is present only in plants and microorganisms, and it is the target of >50 commercial herbicides. Penoxsulam (PS), which is a highly effective broad-spectrum AHAS-inhibiting herbicide, is used extensively to control weed growth in rice crops. However, the molecular basis for its inhibition of AHAS is poorly understood. This is despite the availability of structural data for all other classes of AHAS-inhibiting herbicides. Here, crystallographic data for Saccharomyces cerevisiae AHAS (2.3 Å) and Arabidopsis thaliana AHAS (2.5 Å) in complex with PS reveal the extraordinary molecular mechanisms that underpin its inhibitory activity. The structures show that inhibition of AHAS by PS triggers expulsion of two molecules of oxygen bound in the active site, releasing them as substrates for an oxygenase side reaction of the enzyme. The structures also show that PS either stabilizes the thiamin diphosphate (ThDP)-peracetate adduct, a product of this oxygenase reaction, or traps within the active site an intact molecule of peracetate in the presence of a degraded form of ThDP: thiamine aminoethenethiol diphosphate. Kinetic analysis shows that PS inhibits AHAS by a combination of events involving FAD oxidation and chemical alteration of ThDP. With the emergence of increasing levels of resistance toward front-line herbicides and the need to optimize the use of arable land, these data suggest strategies for next generation herbicide design.

Acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS; EC 2.2.1.6) is the first enzyme in the branched chain amino acid biosynthesis pathway. It catalyzes the conversion of two molecules of pyruvate to 2-acetolactate or one molecule of pyruvate and one molecule of 2-ketobutyrate to 2-aceto-2-hydroxybutyrate. This enzyme is found in plants, bacteria, and fungi but not in animals, making it an important target for biocide discovery. Inhibitors of AHAS [e.g., sulfonylureas (1), imidazolinones (2), triazolopyrimidine sulfonamides (3), and pyrimidinyl-benzoates (4)] have been highly successful commercial herbicides for more than 30 y (1). Furthermore, there is a growing interest in targeting AHAS for the discovery of new antimicrobial agents against pathogenic bacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Mycobacterium tuberculosis) (5–7) and fungi (e.g., Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans) (8–11). These inhibitors that target AHAS have field application rates as low as 2 g/ha, and thus, they have exceptional herbicidal activity, which is attributed not only to their direct binding to AHAS but also, to other specific effects that they induce, such as the oxidative inactivation of the enzyme and the chemical alteration of the thiamin diphosphate (ThDP) cofactor (12, 13).

Oxidative Inactivation

Oxidative inactivation of AHAS is a process that involves the oxidation of the FAD cofactor, leading to the inhibition of the enzyme (12). This type of inhibition has been described as accumulative and reversible, and it relies on the fact that a reduced FAD cofactor is required for the enzyme to be active (14). The reversible accumulative inhibition described here is not equivalent to the “reversible time-dependent inhibition” described by Morrison and Walsh (15). Reversible time-dependent inhibition generally describes a process in which the inhibitor–enzyme complex requires time to acquire a conformation in which the inhibitor is fully effective. In that mode of inhibition, reversibility relates to the binding alone, with the inhibitor being able to dissociate from the complex. However, reversible accumulative inhibition is different. In this case, the herbicide binds to the enzyme, promotes its inactivation, and then, is released and available to cause inactivation of additional enzyme molecules. This leads to the accumulation of inactivated enzyme. Here, the reversibility relates to the enzyme inactivation and not to the binding of the inhibitor. In other words, it denotes the ability of the enzyme to recover its activity after being inactivated by the inhibitor. Reversible accumulative inhibition is a time-dependent process, as the accumulation of enzyme inactivated increases with time until equilibrium is reached between the rate of accumulation of inactivated enzyme and the rate of enzyme recovery. Therefore, we refer to this type of inhibition as “reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition.”

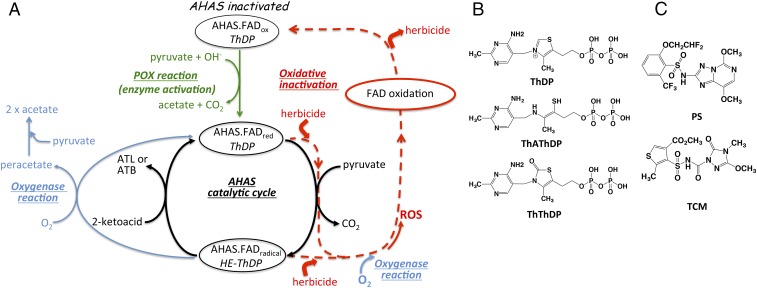

The characteristic slow rate of FAD reduction by the pyruvate oxidase (POX) side reaction of AHAS is one of the causes of the “accumulative” and “reversible” inhibition (12). The origin of the oxidative inhibition is attributed to the inherent oxygenase side reaction of AHAS (Fig. 1A), where reactive oxygen species produced by this reaction [peracetate, singlet oxygen (16)] trigger oxidation reactions that ultimately lead to the oxidation of FAD. The first-order rate constants that define the reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition, the rate of accumulative inhibition (kiapp) and the reversal rate (k3), have values that depend on the structure of the enzyme and the chemistry of the inhibitor (12).

Fig. 1.

Processes and chemicals involved in inhibition of AHAS. (A) Scheme representing the oxidative inhibition of AHAS by herbicides. ATB, acetohydroxybutyrate; ATL, acetolactate; ROS, reactive oxygen species. (B) Structures of ThDP, ThAthDP, and ThThDP. (C) Structures of PS and TCM.

Chemical Alteration of ThDP

ThDP is an essential cofactor of AHAS, as it forms covalent intermediates of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction (17). Herbicides have been shown to modify ThDP (13) into a degraded form, where the C2 carbon is removed [i.e., thiamin aminoethenethiol diphosphate (ThAthDP)] (Fig. 1B), or produce an oxidized form, where a carbonyl oxygen is attached to the C2 carbon [i.e., thiamine thiazolone diphosphate (ThThDP)] (Fig. 1B). Both ThAthDP and ThThDP are unable to sustain AHAS catalysis, and only their replacement by an intact ThDP can restore the activity. This mode of inhibition has been proposed to be important under physiological conditions where the concentration of free ThDP is low, such as in meristem tissues of weeds (13).

The molecular events that are at the base of these inhibition processes have remained unknown. Here, the structures of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc) and Arabidopsis thaliana (At) AHAS in complex with the commercial inhibitor, penoxsulam (PS) (Fig. 1C), reveal the chronological steps involved in the mechanism of reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition and the molecular features that determine the nature and efficiency of AHAS inhibition by PS and in general, by the AHAS-inhibiting herbicides.

Results

Crystal Structure of ScAHAS in Complex with PS.

The crystal structure of ScAHAS in complex with PS (ScAHAS:PS) was determined at 2.33-Å resolution (SI Appendix, Table S1). Notably, PS belongs to the triazolopyrimidine sulfonamide family, which is the only chemical family of commercial herbicides for which no structural data are presently available. The ScAHAS:PS crystal structure has two dimers in the asymmetric unit with a single PS molecule bound at each subunit interface. The overall structure of the ScAHAS:PS is similar to the AHAS complexes when the sulfonylureas are bound (12, 13, 18) and indeed, to all other AHAS inhibitor complexes (13, 18). For example, after superimposition of all of the Cα atoms in the ScAHAS:PS and the ScAHAS:chlorimuron ethyl [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 1N0H] complexes, the rmsd value is only 0.38 Å. PS is inserted deep into a pocket on the surface of the enzyme (Fig. 2A) and is stabilized by interactions with eight segments of the polypeptide (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The superposition of ScAHAS:PS with the structure in complex with pyruvate (ScAHAS:pyr; PDB ID code 6BD9) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) shows that the most significant conformational changes involve the folding of the inhibitor capping region, which is composed of the “mobile loop” and the “C-terminal arm” (19), and the rotation of one of the β-domains. The orientation of the β-domain is adjusted concomitantly with the conversion of FAD from a flat to bent conformation when PS binds. In addition to the presence of PS, several important observations can be made from the crystallographic data that have not been seen when other herbicides bind to AHAS. These are described in the sections below.

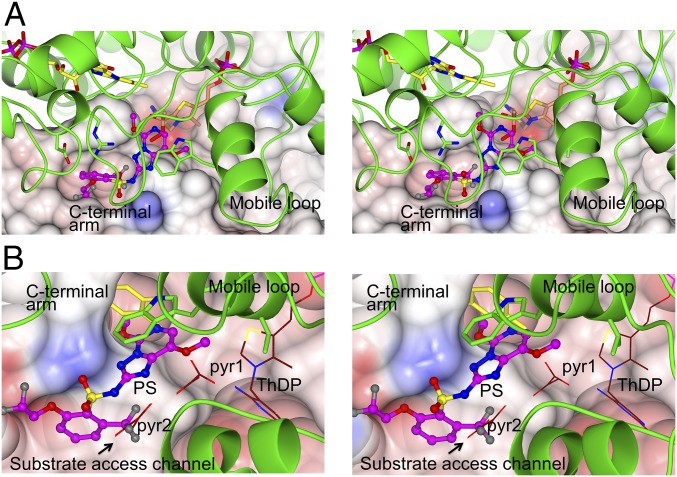

Fig. 2.

Stereo images of the CC and herbicide binding regions of ScAHAS:PS. (A) The fold of a subunit of the ScAHAS:PS complex in the herbicide binding region. In this subunit, the ThDP-peracetate adduct is present. The polypeptide is in green, the FAD is in yellow, and ThDP-peracetate has light brown carbon atoms. PS has magenta carbon atoms and is in ball and stick representation. (B) A superposition of the subunit in A with the CC_FADbent subunit of ScAHAS:pyr. The two pyruvate molecules (pyr1 and pyr2) and ThDP have thin brown bonds that involve carbon atoms. In both images, the Connolly surface is overlaid and color-coded according to electrostatic charge.

PS Competes with the Pyruvate Molecules in the Substrate Access Channel.

It is important to consider that ScAHAS is an asymmetric homodimer with allosteric communication occurring between the two catalytic centers (CCs) (20). During catalysis, the two CCs have different conformations, performing different stages of the AHAS reaction at a single time point (20). The outcome is that, when AHAS is active, it constantly displays two different CC conformations, one with ThDP and reduced FAD with a bent isoalloxazine ring (CC_FADbent) and the other with hydroxyethyl (HE)-ThDP and FAD (oxidized or present as a semiquinone) that has a flat isoalloxazine ring (CC_FADflat). This implies that the binding mode of any herbicide depends on which of the two CCs is present.

A general overview is that the capping region on the surface of the enzyme is responsible for binding the inhibitor, thereby blocking access to the active site by the substrate (13). A superimposition of the ScAHAS:PS structure with CC_FADbent in the structure of ScAHAS in complex with ScAHAS:pyr shows that the capping region does not directly interfere with the substrate but instead, is responsible for locking PS to the surface of the substrate access channel (Fig. 2B). The aromatic group of PS seems to be in direct binding competition with the second molecule of pyruvate (pyr2). A potential steric clash occurs between the triazolopyrimidine group of PS and the first molecule of pyruvate (pyr1) but without direct competition for binding to the enzyme (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). R380 seems to be the main physical obstacle for the binding of PS in this CC conformation.

When the structure of ScAHAS:PS is superposed with the CC_FADflat of ScAHAS:pyr, PS seems to compete with the two pyruvate molecules in a similar way to that in CC_FADbent (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). However, FADflat would appear to obstruct the binding of PS.

ThDP-Peracetate Intermediate.

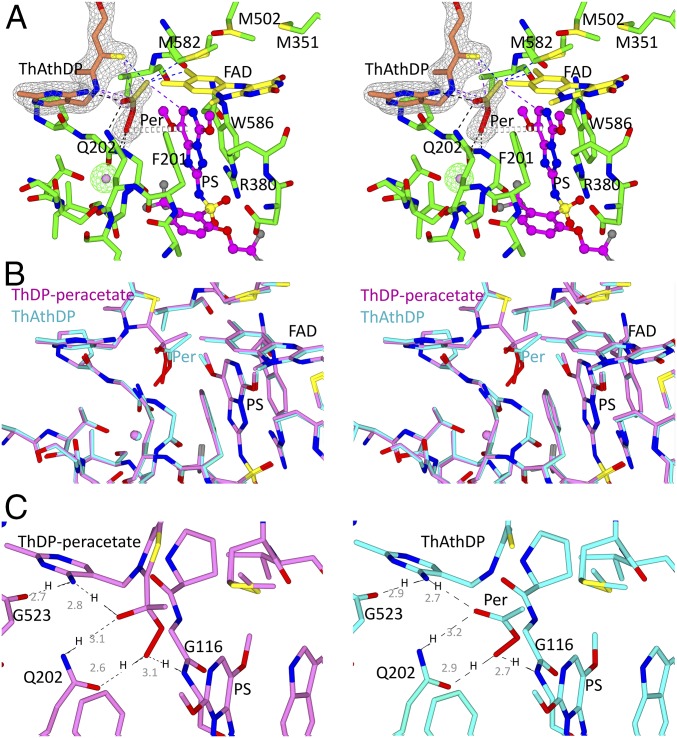

A significant electron density was found attached to the reactive C2 carbon of ThDP in one of four CCs of the four subunits in the asymmetric unit of ScAHAS. Attempts to fit the density as the HE-ThDP intermediate or placement of individual water molecules or components of the crystallization buffer were all unsuccessful. However, peracetate covalently attached to ThDP (ThDP-peracetate), at 60% occupancy, perfectly fits this density (Fig. 3, Upper). This subunit is referred to here as CC_ThDP-peracetate. The peracetate group of ThDP-peracetate is stabilized by several interactions with the inhibitor and the polypeptide. (i) The methyl group of peracetate interacts with the pyrimidinyl group of PS, with M582, and with the C7 methyl of FAD (Fig. 3, Upper shows all of the interactions). (ii) The oxygen atom of the hydroxyl group of peracetate makes a hydrogen bond with the amine group of the side chain of Q202. (iii) The distal oxygen of the peroxoate makes hydrogen bonds with the carbonyl group of Q202 and the backbone amine of G116 and a donor–π interaction with the pyrimidinyl group of PS.

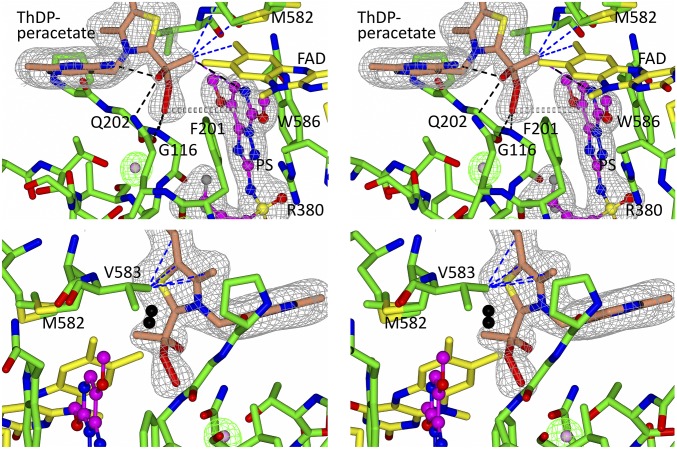

Fig. 3.

Stereo views of CC_ThDP-peracetate in ScAHAS:PS. Two views highlight the interactions that stabilize the peracetate adduct in the CC. Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds (black), van der Waals interactions (purple), and hydrophobic interactions (blue). Gray dashed cylinders represent a donor–π interaction. Electron densities (2Fo–Fc map) in gray correspond to ThDP-peracetate and PS contoured at 1.2σ and 1.9σ, respectively. The ScAHAS:PS polypeptide chains have green carbon atoms. The black molecule in Lower represents O2(I) as observed in ScAHAS:pyr. A water molecule is placed in the Fo–Fc omit electron density (green) contoured to 5σ.

O2(I) and O2(II) Are Displaced by PS.

In the ScAHAS:PS structure, a molecule of water has replaced O2(I) (20) as suggested by the spherical (rather than elongated) shape of the Fo–Fc electron density (Fig. 3). A comparison of the surface of the O2(I) binding pocket between ScAHAS:PS and ScAHAS:pyr shows that the presence of ThDP-peracetate and the new position taken by the side chain of Q202 (see below) preclude the binding of O2 in that site (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

O2(II), which binds to the thiazolium ring of ThDP in uninhibited ScAHAS (20), is also not present in the ScAHAS:PS structure, a consequence of the movement of the mobile loop that brings V583 in the region of the O2(II) binding site (Fig. 3, Lower). In this configuration, the side chain of V583 makes several hydrophobic interactions with the carbon and sulfur atoms of the thiazolium ring of ThDP-peracetate.

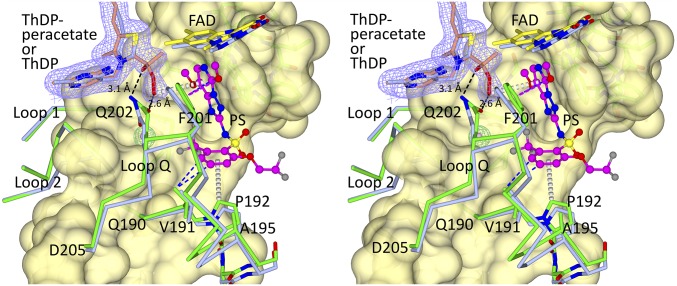

The Movement of “Loop Q.”

Compared with CC_FADbent in ScAHAS:pyr, the side chain of Q202 has moved toward ThDP-peracetate to make an interaction with the two oxygen atoms of the peracetate adduct (Fig. 4). The ScAHAS:PS structure shows that the aromatic ring of PS plays an important role in this process by forming hydrophobic interactions with V191 and a carbon–π interaction with P192 belonging to loop Q (Q190–D205), having the effect of translocating loop Q (and Q202) in the direction of ThDP-peracetate by around 1.1 Å (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). To a lesser extent, the hydrophobic interactions between F201 with the pyrimidinyl group of PS also facilitate this movement (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). In agreement with the additional noncovalent bonds stabilizing this region, there is also a decrease of ∼10 Å2 in the mean B factors of residues in loop Q compared with the enzyme in complex with pyruvate alone (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Fig. 4.

Stereo view of the superposition of ScAHAS:PS and ScAHAS:pyr. In ScAHAS:pyr, the polypeptide, ThDP, and FAD are in light blue stick models. In ScAHAS:PS, the polypeptide is green, ThDP-peracetate has light brown carbon atoms, FAD has yellow carbon atoms, and PS has magenta carbon atoms and is in a ball and stick model. Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds (black), van der Waals interactions (purple), and hydrophobic interactions (blue). Gray dashed cylinders represent donor/carbon–π interactions. The mauve electron density (2Fo–Fc map) corresponds to ThDP-peracetate contoured at 1.2σ.

PS Induces the Breaking of the ThDP-Peracetate Adduct.

In three of four CCs of the ScAHAS:PS crystal structure [and in the structure of AtAHAS in complex with PS (AtAHAS:PS); see below], a free molecule of peracetate can be fitted nearby to a degraded ThDP where the C2 carbon has been removed (Fig. 5A). This degraded ThDP corresponds to ThAthDP (Fig. 1B). We refer to these three CCs as “CC_ThAthDP:peracetate.”

Fig. 5.

Structure of CC_ThAthDP:peracetate in ScAHAS:PS. (A) Stabilization of ThAthDP:peracetate in the presence of PS. The color scheme is as indicated in Fig. 3. Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds (black), van der Waal interactions (purple), and hydrophobic interactions (blue) made by peracetate. Gray dashed cylinders represent a donor–π interaction. Green electron densities are as indicated in Fig. 3. Gray electron densities (2Fo–Fc map) correspond to ThAthDP and peracetate contoured at 3σ and 1σ, respectively. (B) Stereo view of the superposition of CC_ThDP-peracetate and CC_ThAthDP:peracetate of ScAHAS:PS. CC_ThDP-peracetate is in magenta, and CC_ThAthDP:peracetate is in cyan. (C) Comparison of the interactions made by the peracetate adduct in CC_ThDP-peracetate (Left) and free peracetate in CC_ThAthDP:peracetate (Right). All of the distances (light gray text) are in angstroms. Per, peracetate.

Noticeably, the free peracetate molecule is stabilized in the active site by similar interactions to those stabilizing the peracetate adduct in CC_ThDP-peracetate, a consequence of it taking a similar position in both structures (Fig. 5B). However, a difference is that the hydroxyl group of peracetate in ThDP-peracetate is replaced by a carbonyl group in free peracetate. In CC_ThDP-peracetate, the hydroxyl group of the peracetate acts as a hydrogen bond donor with the amine group [in its amino form NH (21)] of the pyrimidine ring of ThDP-peracetate (Fig. 5C, Left), whereas the amino group of the pyrimidine must act as the hydrogen bond donor with the carbonyl group of G523. In the configuration where free peracetate is present, the nitrogen of the pyrimidine ring is assumed to be as the aminopyrimydinium cation [NH2+ (21)], providing the two hydrogen bond donor atoms: one each going to the carbonyl groups of G523 and peracetate (Fig. 5C, Right).

The observation that peracetate is strongly stabilized through interactions with the polypeptide, PS, and ThAthDP suggests that the presence of ThAthDP (Fig. 5A) is concomitant with the production of peracetate, with both molecules arising from the chemical decomposition of the ThDP-peracetate intermediate. To validate this assertion, we monitored the effect that the O2 concentration has on the chemical alteration of ThDP. As anticipated (12, 13), in assays where O2 is depleted (through nitrogen bubbling) (Materials and Methods), the amount of AtAHAS inhibited by PS is greatly decreased (SI Appendix, Fig. S7A). In similar assay conditions, the concentration of intact ThDP was measured by fluorescence spectroscopy (22), indicating that depletion of O2 abolishes the chemical alteration of ThDP by PS (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). As the main product of the ThDP chemical alteration by PS corresponds to ThAthDP (MS data are shown below), we conclude that the production of ThAthDP is dependent on the oxidative process occurring during inhibition, involving the formation of a ThDP-peracetate intermediate and adding additional support to our assertion that these molecules are derived from the decomposition of ThDP-peracetate.

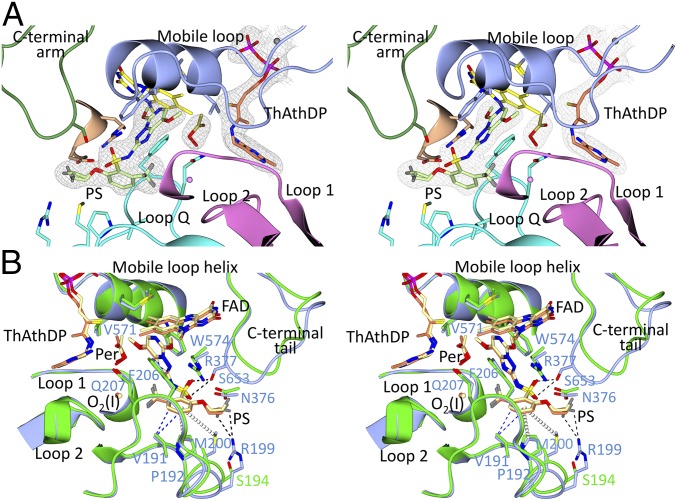

Comparison of PS Binding in ScAHAS and AtAHAS.

The crystal structure of AtAHAS:PS was determined at 2.5-Å resolution (SI Appendix, Table S1). The AtAHAS:PS structure is a tetramer with four identical subunits related by crystallographic symmetry. The overall structure of the subunit is similar to AtAHAS in complex with herbicides from the other four chemical families (13, 18). As in three subunits of ScAHAS:PS, a free molecule of peracetate in presence of ThAthDP could be fitted in the CC of this enzyme (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Stereo views of the CC and herbicide binding regions of AtAHAS:PS. (A) The overall fold of AtAHAS:PS in the herbicide binding region. FAD has yellow carbon atoms, ThAthDP has light brown carbon atoms, peracetate has dark yellow carbon atoms, and PS has light green carbon atoms. Gray electron densities (2Fo–Fc map) correspond to ThAthDP, peracetate, and PS molecules contoured at 1.5σ, 1.3σ, and 1.5σ, respectively. (B) The superposition of CC_ThAthDP:peracetate from ScAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:PS. The ScAHAS and AtAHAS polypeptides are colored in green and light blue, respectively. FAD, ThAthDP, peracetate, and PS are shown as stick models in yellow (ScAHAS) and light brown (AtAHAS). Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds (black) and hydrophobic interactions (blue). Gray dashed cylinders represent carbon/sulfur–π interactions occurring between PS and loop Q in AtAHAS:PS. Per, peracetate.

Overall, the sequence identity between ScAHAS and AtAHAS is only 43%; however, the residues that contact the PS binding site are virtually fully conserved (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). All 13 common residues that contact PS are identical. In addition, there are five extra residues in AtAHAS that make contact with PS that do not make contact with ScAHAS (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). These are S168 and G654, which are also conserved across the two species. However, R199, M200, and S653 in AtAHAS are replaced by the shorter residues serine, alanine, and glycine, respectively, in ScAHAS and thus, are not bulky enough to interact with PS. In addition to the herbicide binding site, loop 1 and loop 2 of the oxygen binding site, loop Q, the C-terminal region, and the mobile loop are also highly conserved not only between the plant and fungal enzymes; conservation also extends into the bacterial AHASs, suggesting that these regions have common functions across all three kingdoms of life (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B).

The mode of binding of PS is identical in the two enzymes in the region where the triazolopyrimidine is located and involves residues that are conserved (in AtAHAS: M570, V571, and W574 from the mobile loop helix as well as R377 and F206) (Fig. 6B). However, some marked differences occur in the binding of the aromatic ring of PS. In AtAHAS, PS also interacts with R199 and M200, residues that are different in ScAHAS (Fig. 6B). In addition, the C-terminal tail in AtAHAS is much closer to the herbicide. This is due to the formation of hydrogen bonds between the side chain of S653 and the sulfonyl oxygen atoms in the linker of PS. As indicated above, in ScAHAS, S653 is replaced by a glycine. Thus, no equivalent hydrogen bonds can occur. Another difference in binding is the fact that the difluoroethoxy moiety attached to the aromatic ring has two alternative conformations in the AtAHAS structure but only one when bound to ScAHAS.

The binding constant of PS is similar in ScAHAS (2.2 ± 0.4 nM) and AtAHAS (1.9 ± 0.9 nM) (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). However, the amount of enzyme inhibited by PS is significantly lower in AtAHAS compared with ScAHAS (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B), with average kiapp and k3 values of 6.5 ± 0.7 and 0.039 ± 0.003 min−1, respectively, for the inhibition of ScAHAS and kiapp and k3 values of 1.7 ± 0.13 and 0.025 ± 0.001 min−1, respectively, for the inhibition of AtAHAS (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). The k3 value is 38% lower in AtAHAS compared with ScAHAS; thus, it has a positive effect on the inhibition. However, the rate constant of accumulative inhibition kiapp is about four times lower in AtAHAS, which seems to be the main driver for the lower amount of overall inhibition of AtAHAS (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B).

The inhibition of AHAS by the herbicides involves the oxidation of the FAD cofactor (12). The reactivation of the enzyme requires the rereduction of FAD through the POX side activity of AHAS, a slow process accounting for the lag phase observed when AHAS is in reaction (14). Here, the monitoring of the lag phase shows that the rate of enzyme activation (kact) is lower in AtAHAS (0.2 ± 0.03 min−1) compared with ScAHAS (0.37 ± 0.03 min−1) (SI Appendix, Figs. S8C and S10), a factor that presumably accounts for the lower reversal rate of k3 found in AtAHAS. However, it is remarkable that, in both ScAHAS and AtAHAS, k3 is 8–10 times lower than kact, implying that the oxidation of FAD only partially accounts for the observed reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition and that another process must be involved.

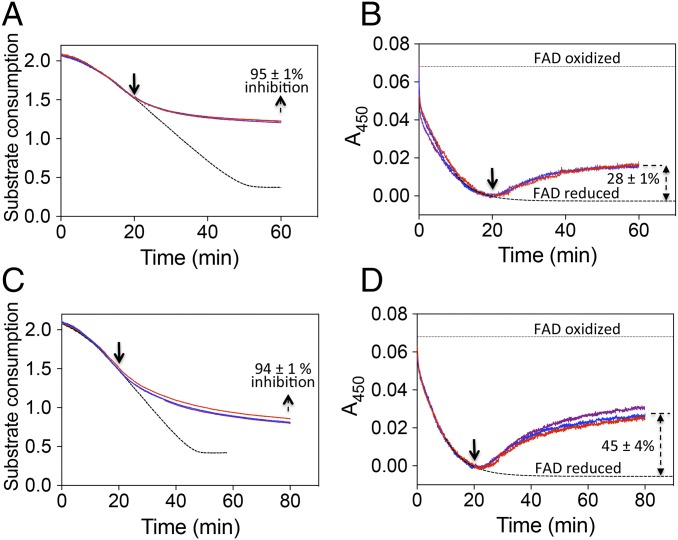

ThDP Chemical Alteration Is Involved in AHAS Inhibition by PS.

To investigate the nature of the process that is responsible for the low values of k3 compared with kact, we monitored the redox state of FAD during the reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition of AtAHAS by PS. The results show that, in a situation where PS inactivates 95 ± 1% of AtAHAS, 28 ± 1% of the FAD cofactor is oxidized (Fig. 7 A and B). In this assay, the value of k3 (0.0072 ± 0.0008 min−1) is around 10 times lower than kact (0.085 ± 0.004 min−1) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) when measured in an identical assay where the pyruvate concentration is equal to 260 mM, corresponding to the concentration of pyruvate when PS was injected (Fig. 7A). This implies that the rate of FAD rereduction after inactivation by PS is altered. The percentage of FAD that would be oxidized when 95% of the enzyme is inactivated should not exceed 8–9% (0.95 × k3/kact) of the total enzyme-bound FAD. Based on the AtAHAS:PS and ScAHAS:PS structures showing that ThAthDP and free peracetate cohabit the CC (Figs. 5 and 6), it is assumed that the low k3 value, compared with kact, is the consequence of FAD rereduction being affected by the presence of ThAthDP.

Fig. 7.

Tracking FAD oxidation during AtAHAS reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition by PS and TCM. (A and C) Progress curves (measured in triplicate) for AtAHAS activity monitored at 365 nm (pyruvate absorbance). The inhibition curves were fitted using Eq. 3, giving kiapp and k3 values of 1.13 ± 0.03 and 0.0072 ± 0.0008 min−1 (SD of the three values), respectively, for PS and kiapp and k3 values of 0.58 ± 0.005 and 0.0048 ± 0.0006 min−1 (SD of three values), respectively, for TCM. (B and D) Progress curves for the FAD reduction/oxidation monitored at 450 nm. The percentages of enzyme-bound FAD reoxidized at the end of the assays are indicated in B and D. In A–D, 375 mM pyruvate was incubated with 20 μM AtAHAS at 20 °C in standard buffer. Assays carried out in the absence of inhibitor are represented by the dashed curves. The solid black arrows indicate the time point for the injection of 2 μM PS (A and B) or 2 μM TCM (C and D) in the sample cell.

Taken together, our kinetic and crystallographic data suggest that inhibition triggered by PS arises from the combination of the production of reactive oxygen species and ThDP degradation, processes that would be simultaneously induced by this herbicide.

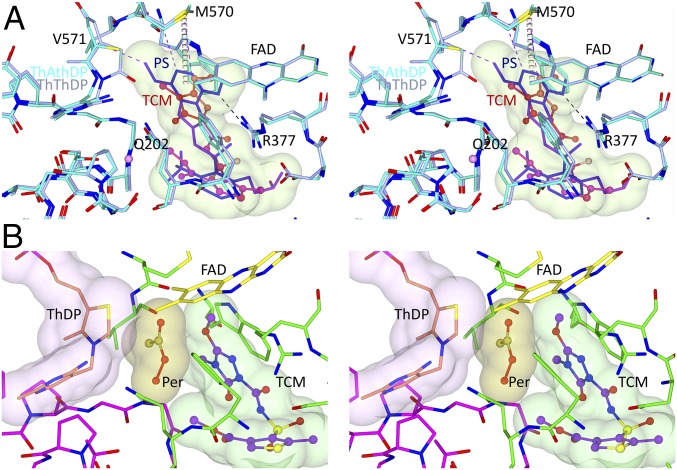

Chemical Alteration of ThDP in the Presence of Thiencarbazone Methyl.

ThThDP (Fig. 1B) has been observed in structures of AtAHAS with herbicides of the sulfonylamino-carbonyl-trazolinone family [propoxycarbazone (PC) and thiencarbazone methyl (TCM)] (13). Using MS, Garcia et al. (13) could confirm the production of ThThDP during inhibition of AtAHAS by PC; however, the presence of ThAthDP was not observed. Here, we investigated further the mechanism underlying the production of ThThDP by comparing the effects of PS and TCM on the integrity of ThDP and comparing the structures of AtAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:TCM. MS analysis of a solution of AtAHAS incubated with PS in running buffer (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) shows a significant peak corresponding to a fragment derived from the cleavage of ThAthDP, but it shows a smaller peak (∼20% intensity) for ThThDP, suggesting that the chemical alteration of ThDP goes in the majority toward ThAthDP, a fact that is endorsed by the structural data. In contrast, for AtAHAS incubated with TCM, only ThThDP was significant (SI Appendix, Fig. S12), confirming the results obtained for PC (13).

When the structures of AtAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:TCM are compared, the main difference is that the pyrimidinyl group of PS more completely fills the herbicide binding pocket compared with the triazolinone group of TCM (Fig. 8A). As a result, the pyrimidinyl group is stabilized by interactions with residues of the polypeptide (R377, M570, and V571), whereas these interactions are absent when TCM binds. Consistent with that observation, the temperature factor of the triazolinone group of TCM is 73.6 Å2 (compare with 56.8 Å2 for the polypeptide), and it is about double that of the pyrimidine group of PS, which is 35.2 Å2 (compare with 44.1 Å2 for the polypeptide). As a consequence of the smaller and more flexible triazolinone group of TCM, a free molecule of peracetate could be docked in the CC of AtAHAS in the presence of an intact ThDP cofactor without any clashes with the polypeptide or with the herbicide (Fig. 8B). All together, these data support the concept that the decomposition of ThDP-peracetate into ThDP and a free peracetate molecule can occur in the presence of TCM.

Fig. 8.

Stereo view of the binding of PS and TCM to AtAHAS. (A) Superposition of the CCs of AtAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:TCM (i.e., PDB ID code 5K6R). Except for the herbicide, all of the carbon atoms in the CC of AtAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:TCM are in cyan and light blue, respectively. PS (stick model and surface representation) and TCM (ball and stick model) are colored according to the B factor of each atom using a blue to red scale for lowest to highest B factor. Dashed lines represent hydrogen bonds (black) and van der Waals interactions (purple). Gray dashed cylinders represent a sulfur–π interaction made by the triazolopyrimidyl ring of PS with M570 of AtAHAS. (B) A model for the AtAHAS:peracetate complex. This image was obtained by docking of peracetate and ThDP (replacing ThThDP) into the CC of AtAHAS:TCM (Materials and Methods). Per, peracetate.

We then investigated the redox status of the FAD cofactor when AtAHAS is inhibited by TCM. The data (Fig. 7 C and D) show that, when 94 ± 1% of the enzyme is inactivated by TCM, the fraction of enzyme-bound FAD that is oxidized reaches 45 ± 4%. As the value of k3 (0.0048 ± 0.0008 min−1) (Fig. 7C) is more than 15 times lower than kact (0.085 ± 0.004 min−1) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), this result implies that, similar to PS, the rate of rereduction of FAD is altered. A logical explanation is that, on decomposition of ThDP-peracetate to ThDP and free peracetate, ThDP is oxidized by peracetate or an O2 molecule released on the binding of TCM. The product, ThThDP, then acts as an inhibitor, delaying the rereduction of FAD until it is replaced by an intact ThDP molecule.

Discussion

The Binding of PS.

Before analyzing the mechanism involved in the reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition of AHAS by PS, it is worth discussing the mode of binding of PS in the two different CCs (CC_FADbent and CC_FADflat) that are simultaneously present (20).

In all structures of AHAS in complex with the herbicides, including ScAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:PS presented here, FAD is bent with the herbicide interacting with the isoalloxazine ring of FAD. Thus, in CC_FADbent, FAD appears to have an optimal conformation for binding PS (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Only the conserved arginine (R380 and R377 in ScAHAS and AtAHAS, respectively) clashes with PS; however, it likely represents a minor obstacle, as it makes new interactions with the sulfonyl linker and the substituted aromatic ring of PS (Fig. 6B and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). In contrast, in CC_FADflat, PS clashes with the isoalloxazine ring, which represents a steric clash for the binding of the inhibitor (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). However, a new hydrophobic interaction is created between the methyl group of HE-ThDP and PS, a factor that may facilitate the binding of the herbicide in this CC.

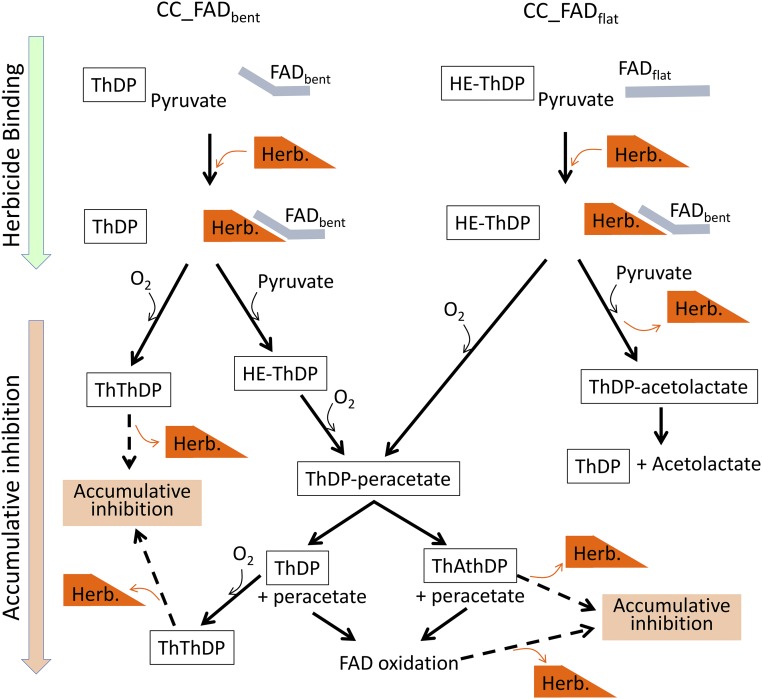

In view of these considerations, it is anticipated that PS and generally all herbicides have different affinities for the CCs of the AHAS dimer. The relative affinity for both CCs may vary as a function of the inhibitor structure, and it is a factor that may play a role in the path leading to the reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition (see below) (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Scheme representing possible paths for the reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition by herbicides.

The Mechanism of Reversible Time-Dependent Accumulative Inhibition by PS.

Reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition is an oxidative process attributed to the promotion of the oxygenase side reaction by the herbicide, leading to the production of reactive oxygen species, such as peracetate and singlet oxygen, that are present in the active site and triggering the oxidative inactivation of the enzyme (12, 16). However, the particular molecular events involved in this type of inhibition are not known. For example, the origin of O2, the substrate of the oxygenase reaction essential for inhibition, is unclear. How a free molecule of peracetate can be trapped in the active site has not previously been visualized, and the circumstances underlying the chemical alteration of ThDP by herbicides have remained enigmatic. Here, the structures of ScAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:PS bring valuable snapshots that elucidate the mechanism of time-dependent accumulative inhibition. These include the following.

-

i)

The identification of conformational changes in AHAS induced by the binding of the herbicide that are responsible for expelling O2 molecules from their binding sites.

-

ii)

The visualization of a ThDP-peracetate adduct greatly stabilized by the herbicide and residues from the AHAS polypeptide that have had their conformation changed by the herbicide.

-

iii)

The presence of a stable ThAthDP:peracetate complex in the CC, witnessing that ThAthDP originates from the degradation of ThDP-peracetate in the presence of the herbicide.

Based on these observations, we depict below the steps involved in the mechanism of inhibition by PS.

First step: The release of free O2 in the active site.

To occur, the oxygenase side reaction requires the presence of a free molecule of O2 in the CC to react with HE-ThDP, the intermediate of the AHAS reaction (Fig. 1A). Here, the structural data show that O2(I) and O2(II) are released in the CC on the binding of PS (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). As displayed in the ScAHAS:PS structure, the change of conformation of Q202 induced by PS and the presence of a ThDP-peracetate intermediate restricts the size of the O2(I) binding pocket, impeding the binding of O2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This situation suggests that the translational movement of loop Q resulting in the displacement of Q202 toward ThDP (Fig. 4) is the trigger for the expulsion of O2(I) from its binding site.

O2(II) is expelled by the conserved valine residue (V583 and V579 in ScAHAS and AtAHAS, respectively) that makes a hydrophobic interaction with the thiazole ring of ThDP in the region where O2(II) is located (Fig. 3, Lower). Thus, two O2 molecules are potentially available in the CC for an electrophilic attack on HE-ThDP.

Second step: The formation of ThDP-peracetate.

The presence of an HE-ThDP intermediate in the active site is an indispensable step in the formation of ThDP-peracetate. Our observations suggest that an HE-ThDP intermediate has the potential to be formed in both types of CC, CC-FADbent, or CC_FADflat. When PS binds to CC_FADbent in AHAS when in the presence of pyruvate, it potentially clashes with the two molecules of pyruvate present in the substrate channel (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Whereas the second pyruvate, which is more distant from the ThDP, has to be expelled to allow for the binding of the inhibitor, the first pyruvate has the alternative to leave the CC or to react with ThDP to give rise to HE-ThDP. In this case, because the second pyruvate molecule has been expelled by the inhibitor, free O2 can react with HE-ThDP without any competition by the substrate.

In CC_FADflat, the binding of PS also competes with both molecules of pyruvate present in the substrate channel, with no alternative other than for the second pyruvate to be expelled (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). The first pyruvate has the possibility to react with the HE-ThDP intermediate, which would create a Lactyl-ThDP intermediate that is enabled to trigger oxidative inactivation. However, if, instead, the first pyruvate is expelled, HE-ThDP remains intact and available to react with O2 to form ThDP-peracetate.

Our deduction is that a configuration allowing the formation of ThDP-peractetate (i.e., the presence of HE-ThDP and a free O2 in the active site) can potentially occur in both CCs in the presence of the herbicide.

Our data suggest that the formation of a ThDP-peracetate intermediate is promoted by a strong stabilization by the herbicide as displayed in our structure (Fig. 3, Upper). It is important to point out here the crucial role that the herbicide plays, not only directly stabilizing the ThDP-peracetate but also, inducing conformational changes that lead to new interactions forming between Q202 or M582 (in ScAHAS or the equivalent residues in AtAHAS) and the peracetate adduct. This feature is another key trigger of the time-dependent accumulative inhibition by the commercial herbicides.

Third step: The simultaneous release of peracetate and degradation of ThDP in the presence of PS, causing accumulation of inactivated AHAS.

A crucial observation in the crystal structures that enlightens the mechanism of inhibition is the combined presence of ThAThDP and free peracetate stabilized by PS. It is obvious that the intact ThDP and free peracetate could not be present at the same time when PS is bound due to steric clashes (Figs. 3 and 5A). It seems that free peracetate can be released in the CC through a reaction that liberates the C2 carbon of ThDP-peracetate to give rise to a ThAthDP:peracetate complex. Remarkably, this complex fits very well in the active site being stabilized by PS, with the free peracetate taking a position almost identical to the peracetate adduct of ThDP-peracetate (Fig. 5 B and C). Thus, it seems that the specific molecular environment created by PS is at the origin of a reaction that produces simultaneously peracetate and ThAthDP, two molecules that are detrimental for enzyme activity.

Peracetate, unable to react with pyruvate, can oxidize the FAD cofactor, leading to the inactivation of AHAS. FAD rereduction by the POX side activity of AHAS is the way for the enzyme to be reactivated. However, this reaction requires an intact ThDP cofactor. As ThAthDP has replaced ThDP, the reactivation of the enzyme is delayed until the exchange of ThAthDP with an intact molecule of ThDP occurs. This explains why k3 is around 8–10 times slower compared with kact.

Therefore, we can conclude that the reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition triggered by PS is due to the combination of the oxidation of FAD and the degradation of ThDP, events that commonly originate from the promotion of the oxygenase side reaction of AHAS by this herbicide.

Alternative Paths for Reversible Time-Dependent Accumulative Inhibition.

In view of the data involving the herbicide, TCM, it seems that the path for the reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition by PS is not unique.

TCM is unusual with respect to the MS data showing that inhibition by this herbicide does not lead to the degradation of ThDP to ThAthDP but rather, does lead to its oxidation to ThThDP (SI Appendix, Fig. S12). In contrast to the pyrimidyl ring of PS, the triazolinone moiety of TCM is shorter and is less complementary to the herbicide binding site as witnessed by the higher B factors (Fig. 8). Accordingly, peracetate can be docked in the CC of the AtAHAS:TCM complex, indicating that ThDP and free peracetate can cohabit with TCM (Fig. 8). Thus, it suggests that a normal decomposition of ThDP-peracetate can occur in the CC. However, the kinetic data show that, similar to PS, the rereduction of FADox is altered. A possibility is that, on the decomposition of ThDP-peracetate, ThDP is oxidized by peracetate or an O2 molecule remaining in the active site, leading to a situation where FAD is oxidized in presence of ThThDP. Another possibility that would lead to an identical situation is that the two O2 molecules that are released by the herbicide in the CC directly oxidize FAD and ThDP. In this case, ThDP-peracetate would not be produced.

This example suggests that several paths leading to reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition exist (Fig. 9) and that the path used by each herbicide will depend on its structure and the structure of AHAS.

Weed Resistance.

Site of action resistance to the current AHAS-inhibiting herbicides, including PS, is of major concern (23). Attempts to overcome this problem are now underway through the rational design and synthesis of new chemical classes as AHAS inhibitors (23–25). Strikingly, one of the major mutation sites responsible for resistance (26) is the proline residue (P197 in AtAHAS), which belongs to loop Q and interacts with the aromatic ring of PS (Fig. 6B). Our data help to explain why the conservation of this residue is critical for herbicide inhibition, as a mutation will affect the binding of the herbicide and the movement of loop Q. This is consistent with the fact that herbicides that are highly flexible and have a short linker allow favorable interactions with the bulkier leucine side chain of the P197L mutation rather than creating a steric clash and therefore, a high level of resistance (23, 24, 27).

In general, it is anticipated that more sophisticated inhibitors of AHAS could now be designed that take full advantage of the knowledge of the crystal structure data presented here, the oxygenase side reaction, and the trapping of oxidation products within the active site. This may mean that the need to make tight binding associations with key residues that are known to be common resistance sites (e.g., W574, S653, and P197) can be averted, resulting in herbicides with an enhanced ability to stave off resistance.

Conclusion

The AHAS-inhibiting class of herbicides works in an opportunistic fashion. It is remarkable that these inhibitors were designed more than 30 y ago, before the identification of the target. These herbicides seem to be the perfect inhibitor, taking full advantage of the multiple functions of AHAS; each element of complexity represents an “Achilles heel” that the herbicide uses to achieve inhibition.

The regulation of AHAS by soluble quinones. The herbicide takes advantage of the presence of a binding site for soluble quinone derivatives regulating AHAS activity (14).

The mechanism of AHAS activation–inactivation. AHAS is activated through the reduction of FAD by the POX side reaction of the enzyme, and the oxidation of reduced FAD is at the base of the regulation by quinones (14). It implies that, to sustain the AHAS reaction, reduced FAD has to be protected from oxidation. The herbicides use this constraint to their advantage through their ability to trigger the release of O2 in the CC.

The oxygenase side reaction of AHAS. In normal conditions, the production of peracetate in the CC is not harmful for AHAS, because peracetate reacts with pyruvate to give two innocuous acetate molecules (28). Through the promotion of the oxygenase reaction and the obstruction of the substrate access channel, the herbicide provokes the release of peracetate that can oxidize the enzyme. Here, the herbicide subverts the oxygenase reaction at the detriment of enzyme activity.

The “hyperactivity” of ThDP (29). In AHAS catalysis, the highly reactive carbanion of ThDP reacts with the substrate acceptor to generate HE-ThDP, an intermediate involved in the carboligation of the substrate donor. In AHAS catalysis, the highly reactive carbanion of ThDP serves generating an HE-ThDP intermediate that reacts with the substrate donor. The herbicide seems to be able to divert ThDP toward other chemical reactions, leading to the generation of ThAthDP and ThThDP that inactivate the enzyme.

Material and Methods

Protein Preparation.

The expression and purification of ScAHAS and AtAHAS were carried out as described previously (13, 14). The enzyme samples were cryocooled and stored at −80 °C. Enzyme concentrations were determined by analysis using a Direct Detect spectrophotometer (Millipore).

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Crystals for both structures were obtained by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. For the ScAHAS:PS complex, the cofactors, inhibitors, and DTT were added to freshly thawed enzyme to give final concentrations of 42 mg/mL enzyme, 2 mM ThDP, 1 mM FAD, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM PS, and 8 mM DTT. The crystallization buffer consisted of 1 M succinic acid, pH 7.0, 0.1 M Hepes, pH 7.0, and 1% (wt/vol) PEG monomethyl ether 2000. The crystallization drops consisted of equal volumes (1 µL) of well solution and enzyme complex. For cryocooling, the crystals were transferred to a drop containing well solution and 25% (vol/vol) PEG. To crystallize the AtAHAS:PS complex, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ThDP, 1 mM FAD, 5 mM DTT, and 2.2 mM PS were added to freshly thawed protein (40 mg/mL). The hanging drops were prepared by mixing equal volumes (1 µL) of protein complex and well solution containing 0.1 M Bis⋅Tris propane, pH 6.5, 0.2 M sodium potassium tartrate, and 20% PEG 3350. Before cryocooling, crystals were transferred to a drop containing well solution, 35% (vol/vol) ethylene glycol, cofactors, and inhibitor.

X-ray data for both complexes were collected at the Australian Synchrotron, beam line MX1 (wavelength: 0.9537 Å). For ScAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:PS, datasets of 360 images with an oscillation range of 0.5° were collected with an exposure time of 2 s. The data were integrated using the program XDS (30), and they were scaled and merged using Aimless (31). The phasing was determined by molecular replacement using PHASER (32) and the protein coordinates of the ScAHAS-chlorimuron ethyl complex (33) (PDB ID code 1N0H) or the AtAHAS-pyrithiobac complex (13) (PDB ID code 5K2O). Refinement and model building were achieved using Phenix 1.8 (34) and COOT 0.7 (35), respectively. Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the PDB with ID codes 5WKC and 5WJ1.

MS.

The MS analysis of ThDP was performed as described previously (13). In summary, 700 μM AtAHAS was incubated with 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, 6 mM ThDP, 1 mM FAD, 100 mM sodium pyruvate, and 70 μM inhibitor (PS or TCM) for 5 d at 18 °C. The samples were exhaustively dialyzed against water, and the cofactors were isolated by addition of an equal volume of ice-cold methanol containing 5% (vol/vol) acetic acid and ultrafiltration using a 3-kDa Nanosep device (PALL). Exact masses for the ThDP analogs were determined by high-resolution liquid chromatography-MS using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 RSLC nanosystem coupled to a Bruker micrOTOF-Q mass spectrometer operated in positive mode.

AHAS Assay.

Enzyme assays were performed using a continuous spectrophotometric method measuring the disappearance of pyruvate (36) or a colorimetric method (37). The standard buffer contained 200 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 1 mM ThDP, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 µM FAD. The concentration of pyruvate was variable and is described in the text, methods, and figure legends.

Different temperatures were used in the assays to adapt to the requirements of each experiment. For the calculation of the kinetic rate constants for reversible accumulative inhibition, 30 °C was used, thus allowing comparison with published rates obtained previously for other commercial herbicides (13). For the tracking of FAD oxidation during AtAHAS inhibition by PS and TCM (Fig. 7), 20 °C was used so as to decrease the reaction rate (pyruvate consumption). This allowed a substantial increase in the enzyme concentration, resulting in a more accurate measurement of reduction/oxidation of the enzyme-bound FAD (i.e., absorbance signal is significantly greater than compared with the background noise). Similarly, a low temperature (18 °C) was chosen for the ThDP assay, allowing accurate measurement of the degradation of enzyme-bound ThDP. For the measurement of Ki, a temperature of 37 °C was used to increase the activity and allow for the measurement of AHAS inhibition in a short period of time (30 min), limiting the influence of the accumulation of inactive enzyme during the assay.

ThDP Assay.

The effect of O2 on the herbicide-induced degradation of ThDP was assayed by the thiochrome method as reported previously (28) but with some modifications; 50 μM AtAHAS was incubated in the absence and presence of herbicide (16 μM) in buffer containing 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.2, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 μM ThDP, and 50 μM FAD. Partial anaerobic conditions were achieved by purging the reaction buffer with N2 for 60 min. The reaction was conducted at 18 °C and monitored for 20 min after adding 250 mM pyruvate; 10-μL samples were collected at intervals of 1 min and mixed with 600 μL of 50% (vol/vol) ethanol before adding 100 μL of 0.04% (wt/vol) K3Fe(CN)6 in 15% (wt/vol) NaOH. The reaction was completed by the addition of 2 μL of 30% (vol/vol) H2O2 after 2 min of incubation at room temperature. Fluorescence of the formed thiochrome was measured immediately with a CytoFluor series 4000 fluorescence multiwell plate reader (PerSeptive Biosystems) using excitation at 360 nm and emission at 460 nm, with bandwidths set at 20 nm. The residual cofactor was expressed as the percentage of that present initially, which was determined by reference to standard solutions of 0, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 200 μM ThDP assayed using the same procedure. The enzyme activity was monitored in parallel using the continuous assay.

Measurement of Inhibition Constant Ki.

An essential problem in the measurement of the inhibition constant (Ki) of herbicides is the occurrence of accumulative inhibition during the enzymatic assay, leading to an underestimation of the Ki value. Previously, we have shown that purging O2 from the assay buffer through N2 bubbling for 60 min partially decreased the amount of accumulative inhibition (13). Here, we found that treatment by 140 μM mercaptoethanol drastically decreases accumulative inhibition in AtAHAS and ScAHAS (SI Appendix, Fig. S13) by a mechanism not elucidated yet. Importantly, we found that mercaptoethanol, even at millimolar concentrations, does not affect the AHAS activity or the binding affinity of PS. Thus, to reduce to a minimum the accumulative inhibition during the measurement of Ki, we measured the initial rate of the inhibition of AHAS by PS in buffer containing 140 μM of mercaptoethanol and treated with N2 bubbling for 60 min.

AHAS inhibition by PS activity was measured using the colorimetric method; 9/12 nM ScAHAS/AtAHAS was incubated at 37 °C in standard buffer containing 100 mM pyruvate and 140 μM mercaptoethanol purged from O2 as mentioned above (total volume of 1.1 mL). After 10 min of incubation corresponding to the lag phase, 100-μL aliquots were taken, to which was added 14 μL of 50% (vol/vol) H2SO4 (this corresponds to time 0 of the inhibition), 2 μL of DMSO (control), or 2 μL of a PS solution (dissolved in DMSO) covering a range of PS final concentrations down to 2.5 nM. The samples with DMSO and PS were further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. The inhibition reaction was then stopped by adding 14 μL of 50% H2SO4. The colorimetric assay was performed as follows. The samples treated with H2SO4 (see above) were incubated at 60 °C for 15 min (formation of acetoin). Then, 100 μL of creatine (0.5% wt/vol) and 100 μL of α-naphthol [diluted in 4 M NaOH (5% wt/vol)] were added, and the samples were further incubated at 60 °C for 15 min (to allow for color development). Next, 200 μL of the samples were each transferred into a 96-well plate, and absorbance was measured at 525 nm. The activity for each sample, reported as percentage activity of the control, was obtained by subtracting the absorbance of the sample taken at time 0 (see above).

Because PS has a high affinity for AtAHAS and ScAHAS, the concentration of enzyme exceeded the lowest concentration used for the inhibitor, and the equation for reversible tight-binding inhibition (Eq. 1) (38) had to be used:

| [1] |

where [Ef] and [If] represent the concentrations of free enzyme and inhibitor, respectively.

The Ki values were obtained by nonlinear regression using Eq. 2 derived from Eq. 1:

| [2] |

where [Etot] and [Itot] represent the total concentrations of enzyme and inhibitor present in the assay, respectively, and v0 and vi are the reaction velocities in the absence and presence of inhibitor, respectively.

The raw data were fitted with Eq. 2 using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software; www.graphpad.com).

The equation used in Prism was the following:

Measurement of Reversible Time-Dependent Accumulative Inhibition.

For accumulative inhibition, 1 μM AtAHAS was assayed using the continuous method measuring the disappearance of pyruvate (36). The inhibitors were added 12 min after the enzyme so that inhibition could be measured when maximum activity of the enzyme was achieved. The reversible time-dependent accumulative induced by the herbicides was observed for a 40-min period. All experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the data were fitted using Eq. 3 (12) for the calculation of the rate constants (kiapp and k3) involved in reversible time-dependent accumulative inhibition:

| [3] |

Measurement of the Rate of Activation (kact).

The measurement of the observed rate of activation kact was performed using Eq. 4 (14):

| [4] |

Molecular Docking of Peracetate in AtAHAS:TCM (Fig. 8B).

The structure refinement and energy minimization of AtAHAS:TCM in the presence of intact ThDP and peracetate were calculated with the YASARA Energy Minimization Server (39).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Crystallization and preliminary X-ray data were measured at the University of Queensland Remote-Operation Crystallization and X-ray Diffraction Facility. This work was supported by funds from National Health and Medical Research Council Grant 1087713.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. M.-J.A-J. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: The coordinates and structure factors for ScAHAS:PS and AtAHAS:PS complexes have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.wwpdb.org/ (PDB ID codes 5WKC and 5WJ1, respectively).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1714392115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sauers RF, Levitt G. Sulfonylureas: New high potency herbicides. In: Magee P, Kohn G, Menn J, editors. Pesticide Synthesis Through Rational Approaches. Vol 255. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 1984. pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ladner DW. Structure-activity-relationships among the imidazolinone herbicides. Pestic Sci. 1990;29:317–333. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleschick WA, et al. New herbicidal derivatives of 1,2,4-triazolo[1,5-α] pyrimidine. Pestic Sci. 1990;29:341–355. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drewes MW. Sialicyclic acids and related structures. In: Ebing W, editor. Herbicides Inhibiting Branched Chain Amino Acid Biosynthesis. Vol 10. Springer; Berlin: 1994. pp. 161–187. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreisberg JF, et al. Growth inhibition of pathogenic bacteria by sulfonylurea herbicides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:1513–1517. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02327-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandoni JA, Marta PT, Schloss JV. Inhibitors of branched-chain amino acid biosynthesis as potential antituberculosis agents. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;42:475–482. doi: 10.1093/jac/42.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, et al. Discovery of novel acetohydroxyacid synthase inhibitors as active agents against Mycobacterium tuberculosis by virtual screening and bioassay. J Chem Inf Model. 2013;53:343–353. doi: 10.1021/ci3004545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kingsbury JM, McCusker JH. Cytocidal amino acid starvation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans acetolactate synthase (ilv2Delta) mutants is influenced by the carbon source and rapamycin. Microbiology. 2010;156:929–939. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034348-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kingsbury JM, Yang Z, Ganous TM, Cox GM, McCusker JH. Cryptococcus neoformans Ilv2p confers resistance to sulfometuron methyl and is required for survival at 37 °C and in vivo. Microbiology. 2004;150:1547–1558. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26928-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee YT, et al. Sulfonylureas have antifungal activity and are potent inhibitors of Candida albicans acetohydroxyacid synthase. J Med Chem. 2013;56:210–219. doi: 10.1021/jm301501k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richie DL, et al. Identification and evaluation of novel acetolactate synthase inhibitors as antifungal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2272–2280. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01809-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lonhienne T, et al. Commercial herbicides can trigger the oxidative inactivation of acetohydroxyacid synthase. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2016;55:4247–4251. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia MD, Nouwens A, Lonhienne TG, Guddat LW. Comprehensive understanding of acetohydroxyacid synthase inhibition by different herbicide families. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E1091–E1100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616142114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lonhienne T, Garcia MD, Guddat LW. The role of a FAD cofactor in the regulation of acetohydroxyacid synthase by redox signaling molecules. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:5101–5109. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.773242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison JF, Walsh CT. The behavior and significance of slow-binding enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1988;61:201–301. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schloss JV. Recent advances in understanding the mechanism and inhibition of acetolactate synthase. In: Ebing W, editor. Herbicides Inhibiting Branched Chain Amino Acid Biosynthesis. Vol 10. Springer; Berlin: 1994. pp. 3–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tittmann K, et al. Electron transfer in acetohydroxy acid synthase as a side reaction of catalysis. Implications for the reactivity and partitioning of the carbanion/enamine form of (alpha-hydroxyethyl)thiamin diphosphate in a “nonredox” flavoenzyme. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8652–8661. doi: 10.1021/bi049897t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCourt JA, Pang SS, King-Scott J, Guddat LW, Duggleby RG. Herbicide-binding sites revealed in the structure of plant acetohydroxyacid synthase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:569–573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508701103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia MD, Wang JG, Lonhienne T, Guddat LW. Crystal structure of plant acetohydroxyacid synthase, the target for several commercial herbicides. FEBS J. 2017;284:2037–2051. doi: 10.1111/febs.14102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lonhienne T, Garcia MD, Fraser JA, Williams CM, Guddat LW. The 2.0 Å X-ray structure for yeast acetohydroxyacid synthase provides new insights into its cofactor and quaternary structure requirements. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer D, et al. Unexpected tautomeric equilibria of the carbanion-enamine intermediate in pyruvate oxidase highlight unrecognized chemical versatility of thiamin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:10867–10872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201280109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCourt JA, Nixon PF, Duggleby RG. Thiamin nutrition and catalysis-induced instability of thiamin diphosphate. Br J Nutr. 2006;96:636–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qu RY, et al. Computational design of novel inhibitors to overcome weed resistance associated with acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS) P197L mutant. Pest Manag Sci. 2017;73:1373–1381. doi: 10.1002/ps.4460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu YC, et al. Triazolopyrimidines as a new herbicidal lead for combating weed resistance associated with acetohydroxyacid synthase mutation. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:4845–4857. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b00720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ji FQ, et al. Computational design and discovery of conformationally flexible inhibitors of acetohydroxyacid synthase to overcome drug resistance associated with the W586L mutation. ChemMedChem. 2008;3:1203–1206. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heap I. 2018 The International Survey of Herbicide Resistant Weeds. Available at weedscience.org/summary/MOA.aspx?MOAID=12. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 27.Qu RY, et al. Discovery of new 2-[(4,6-Dimethoxy-1,3,5-triazin-2-yl)oxy]-6-(substituted phenoxy)benzoic acids as flexible inhibitors of Arabidopsis thaliana acetohydroxyacid synthase and its P197L mutant. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65:11170–11178. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chipman DM, Duggleby RG, Tittmann K. Mechanisms of acetohydroxyacid synthases. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2005;9:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Machius M, et al. A versatile conformational switch regulates reactivity in human branched-chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase. Structure. 2006;14:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabsch W. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pang SS, Guddat LW, Duggleby RG. Molecular basis of sulfonylurea herbicide inhibition of acetohydroxyacid synthase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7639–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schloss JV, Van Dyk DE, Vasta JF, Kutny RM. Purification and properties of Salmonella typhimurium acetolactate synthase isozyme II from Escherichia coli HB101/pDU9. Biochemistry. 1985;24:4952–4959. doi: 10.1021/bi00339a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh BK, Stidham MA, Shaner DL. Assay of acetohydroxyacid synthase. Anal Biochem. 1988;171:173–179. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldstein A. The mechanism of enzyme-inhibitor-substrate reactions. J Gen Physiol. 1944;27:529–580. doi: 10.1085/jgp.27.6.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krieger E, et al. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77:114–122. doi: 10.1002/prot.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.