Abstract

Utilizing the host immune system to eradicate cancer cells has been the most investigated subject in the cancer research field in recent years. However, most of the studies have focused on highly variable responses from immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, from which the majority of patients experienced no or minimum clinical benefit. Advances in genomic sequencing technologies have improved our understanding of immunopharmacogenomics and allowed us to identify novel cancer‐specific immune targets. Highly tumor‐specific antigens, neoantigens, are generated by somatic mutations that are not present in normal cells. It is plausible that by targeting antigens with high tumor‐specificity, such as neoantigens, the likelihood of toxic effects is very limited. However, understanding the interaction between neoantigens and the host immune system remains a significant challenge. This review focuses on the potential use of neoantigen‐targeted immunotherapies in cancer treatment and the recent progress of different strategies in predicting, identifying, and validating neoantigens. Successful identification of highly tumor‐specific antigens accelerates the development of personalized immunotherapy with no or minimum adverse effects and with a broader coverage of patients.

Keywords: cancer precision medicine, immune checkpoint inhibitor, neoantigen, next‐generation sequencing, T‐cell receptor repertoire

1. INTRODUCTION

Due to the development of immunotherapies, in particular, immune checkpoint inhibitors as well as recent advances in the technology to sequence cancer genomes and to characterize T‐cell or B‐cell receptors, immunogenomics or immunopharmacogenomics have received a very high level of attention in the cancer research field. Tumor‐infiltrating T lymphocytes, which have been shown to associate with better prognosis in patients with various solid cancers,1, 2 are recognized as an important key factor in cancer immunotherapy. They exert their adaptive immune responses through the recognition of antigens that are specifically expressed on cancer cells. However, the mechanism that allows the immune system to distinguish between benign cells and tumor cells is still not well understood. Recent research has confirmed that neoantigens, which are generated by somatic genetic mutations in cancer cells, can be recognized as “non‐self” antigens by the immune system. Such a unique characteristic highlights the important roles of neoantigens and their potential contribution in immunotherapy.

2. IMMUNE CHECKPOINT INHIBITORS

Immunotherapies such as immune checkpoint antibodies have revolutionized cancer treatments. Immune checkpoint antibodies target the inhibitory molecules that suppress the host immune response against cancer cells and then allow the activation of the host immune system, resulting in eradication of cancer cells. The major targets for such blockade in the clinic are cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated antigen‐4 (CTLA‐4), and the interaction between programmed death‐1 (PD‐1) and PD‐1 ligand‐1 (PD‐L1). Both CTLA‐4 and PD‐1⁄PD‐L1 are key regulators that are responsible for suppression of T‐cell‐mediated antitumor immune responses. However, recent meta‐analysis of clinical data clearly showed that only a subset of patients responded to immune checkpoint inhibitors; the majority of patients had no or minimum clinical benefit and some suffered from severe immune‐related adverse reactions.3 Such observation highlights the importance of identifying a predictive biomarker(s) that can be used to select patients who are more likely to expect clinical benefit with minimal risk of autoimmune adverse events, contributing to reduction of unnecessary medical costs.3

High PD‐L1 expression in cancer cells and high infiltration of immune cells have been suggested to correlate with clinical responses to anti‐PD‐1 therapy.4 Contrarily, it has been shown in several studies that patients who lacked the PD‐L1 expression in cancer tissues showed clinical benefit from anti‐PD‐1 therapy.5 Another PD‐1 ligand, PD‐L2, is also known to suppress cytotoxic activity of T cells in tumors; thereby high PD‐L2 expression could be associated with treatment response.6 Several studies have investigated predictive biomarkers for response to immune checkpoint antibodies.7 We previously reported that the expression levels of granzyme A and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)‐A in melanoma tissues before treated with anti‐PD‐1 antibody were significantly higher in responders compared to non‐responders,8 which could indicate their value as potential biomarkers to predict clinical responses. Recent reports suggest that loss of heterozygosity of HLA class I locus is an immune escape mechanism that is related with poor outcome in patients who received immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy.9, 10 Furthermore, we showed that the T‐cell receptor (TCR) repertoire of tumor‐infiltrated T cells might be useful information for the evaluation or assessment of the immune microenvironment.8 Recent reports, including ours, suggested that durable response to immune checkpoint blockade correlated with early and sustained expansion of a few dominant T‐cell clones in peripheral blood, and that TCR sequencing can be used to detect early signs of response/resistance to immune checkpoint blockade.11, 12

A series of studies have also addressed the relationship between mutational burden and immunotherapeutic outcome. Early studies supported the hypothesis that the extent of DNA damage is correlated with therapeutic response in melanoma patients treated with anti‐CTLA‐4 antibody,13 and non‐small‐cell lung cancer patients treated with anti‐PD1 antibody.14 A more recent study also found the predictive power for neoantigen load in anti‐CTLA‐4‐treated melanoma patients.15 More importantly, mismatch‐repair proficiency was associated with clinical response; it was observed that patients who have a higher number of somatic mutations due to the mismatch‐repair deficiency were more susceptible to PD‐1 blockade therapy compared to patients without the mismatch‐repair deficiency.16 The results from these studies all indicated a strong positive relationship between the numbers of predicted neoantigens, host immunological responses, and overall survival. A high somatic mutation burden should theoretically increase the probability of generating neoantigens. These tumor antigens can then be presented with HLA molecules to the surface of cancer cells and be recognized by CD8+ T cells to enhance antitumor immune responses.

3. CANCER‐SPECIFIC ANTIGENS

The general mechanism of how the host immune system attacks the cancer cells has been well studied. It is believed that as the T cells infiltrate into tumors, they recognize the HLA‐bound cancer‐specific peptides on the cancer cell surface, are activated and proliferate, and kill the cancer cells. The tumor antigens are generally classified into several types: (i) overexpressed antigens that are more highly expressed in cancer cells compared to normal cells (e.g. melanoma‐associated antigen recognized by T cells [MART‐1] and glycoprotein 100 [gp100]); and (ii) tumor‐specific and shared antigens that are expressed in cancer and/or testis, but not in other normal tissues (e.g. melanoma‐associated antigen 1 [MAGE‐A1], NY‐ESO‐1, upregulated gene in lung cancer 10, ring finger protein 43, and kinesin family member 20). These tumor‐specific antigens are also called cancer‐testis antigens because of their expression patterns. However, some of these antigens have also been found in other normal tissues with low expression. In addition, a new group of antigens, neoantigens, have attracted an attention extensively in recent years due to their high specificity to cancer cells. They are generated by somatic mutations in cancer cells and are not present in normal cells, which therefore can be recognized as “non‐self” antigens by the immune system.17 This concept was first examined during the late 1980s by several groups using mouse models.18, 19 Recent advances in next‐generation sequencers enable us to comprehensively study the genomic landscape of tumors and analyze the tumor microenvironment.

An increasing number of studies has reported the associations of mutational burden/predicted neoantigen load and the intratumoral immune infiltrates with patient survival. Rooney et al.20 analyzed whole‐exome sequencing and transcriptome datasets from thousands of solid tumors across 18 tumor types in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). They identified that cytolytic activity of CTLs, estimated from the expression levels of key immune effectors, granzyme A and perforin 1, was correlated with somatic mutation load and the numbers of predicted neoantigens. Brown et al. also analyzed RNA sequencing data for 515 patients from 6 tumor sites from TCGA dataset and reported similar results, in which higher predicted neoantigen load was significantly associated with better prognosis.21 Interestingly, these studies found that tumors with 150‐200 non‐synonymous somatic mutations showed an elevated cytolytic T cell score. Several other studies supported that higher predicted neoantigen load was also associated with lymphocytic infiltration into tumors and survival rate. These associations were observed across both microsatellite stable and unstable tumors in colorectal and ovarian cancer patients.22, 23 In 2014, we also reported similar findings on the association between somatic mutations and survival rate using whole‐exome and target sequencing in 78 muscle‐invasive bladder cancer patients. We found that carriers of somatic mutations in DNA repair genes had significantly better recurrence‐free survival compared with non‐carriers (median, 32.4 vs 14.8 months; hazard ratio, 0.46; P = .044).24 The follow‐up study identified that tumors with higher neoantigen load showed lower TCR diversity, which correlated with oligoclonal tumor‐infiltrating T lymphocyte expansion, and showed a significant association with longer recurrence‐free survival (hazard ratio, 0.37; P = .033).25 We also described the correlation between higher neoantigen load and T‐cell activation among different portions within the same tumors.26, 27

4. NEOANTIGEN PREDICTION

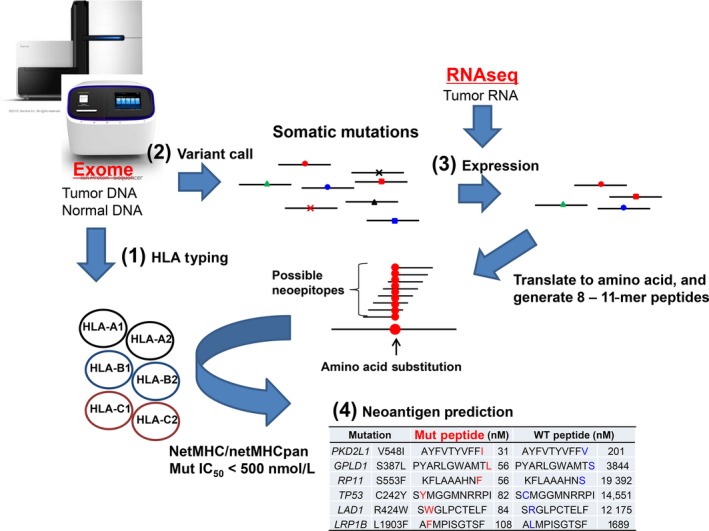

It is still a major challenge to accurately predict the interaction between neoantigens and immune cells. There are currently several publicly available neoantigen prediction pipelines, including pVAC‐Seq,28 INTEGRATE‐neo,29 TSNAD.30 pVAC‐Seq combines the tumor mutation and expression data to predict neoantigens by invoking NetMHC 3.4; INTEGRATE‐neo was designed to predict neoantigens from fusion genes based on the pipeline INTEGRATE and NetMHC 4.0. Similar to these pipelines, TSNAD also uses widely approved software NetMHCpan 2.8 to predict neoantigens. We have also developed a pipeline to predict neoantigens from whole‐exome and RNA sequencing data (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Workflow of a neoantigen prediction pipeline. From whole‐exome sequence data (from normal and tumor DNAs) and RNA sequencing data (RNAseq; from tumor RNA), we obtain information on (1) HLA genotypes, (2) somatic mutations, and (3) the expression levels of mutated genes. Using this information, we estimate affinities of peptides to human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules, and list possible neoantigens (4). Mut, mutant

4.1. Human leukocyte antigen typing based on whole‐exome data

In‐depth understanding of HLA molecules is vital for accurate neoantigen prediction. The HLA class I molecules are critical mediators of the cytotoxic T‐cell responses as they present antigen peptides on the cell surface to be recognized by TCR on T cells. The HLA gene cluster, located on the short arm of chromosome 6, is among the most polymorphic regions in the human genome, with thousands of documented alleles.31 The HLA allele has a unique nomenclature that comprises the gene name indicating the locus (i.e. A, B, or C) followed by successive sets of digits separated by colons.32 The first two digits (field 1) specify the allele groups by serological activity (allele level resolution, ex. A*01 or A*02), and the second field indicates the protein sequence (protein level resolution, ex. A*02:01 or A*02:02). The remaining two sets distinguish synonymous polymorphisms and non‐coding variations. At least 2‐field HLA typing is required to accurately predict neoepitopes, which can bind to HLA molecules. Several tools have been developed to obtain HLA allele information from genome‐wide sequencing data (whole‐exome, whole‐genome, and RNA sequencing data), including OptiType,33 Polysolver,34 PHLAT,35 HLAreporter,36 HLAforest,37 HLAminer,38 and seq2HLA.39 We have tested 961 whole‐exome data from the 1000 Genomes Project to evaluate the accuracy of these programs. Among these algorithms, OptiType showed the highest accuracy of 97.2% for HLA class I alleles at the second field level, followed by 94.0% in Polysolver and 85.6% in PHLAT.40

4.2. Variant call and RNA expression

Somatic mutation calling from whole‐exome sequencing data is achieved by aligning sequence reads to the reference genome, comparing tumor DNAs with matched normal control DNAs to identify single nucleotide variants and insertions/deletions (indels). Although our neoantigen prediction pipeline accepts output from any variant callers, we used the Genomon Exome pipeline to obtain somatic variant information (http://genomon.readthedocs.io/ja/latest/) and extract non‐synonymous mutations and indels to translate them into amino acid sequences. We then use RNA sequencing data of tumors to examine gene expression and predict whether each neoepitope could bind to HLA molecules. Most of the tools use expression filtering based on fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped FPKM or reads per kilobase of exon per million reads mapped RPKM, although they cannot distinguish between WT and mutated RNAs. In our pipeline, we created a script to obtain each of the WT RNA expression and mutated RNA expression separately in addition to the total RNA expression reads. The expression of approximately 45.0% (range, 11.1%‐72.7%) of mutated genes were detected in RNA sequencing reads. It is currently still disputable how many levels of RNA or protein expression are required for CTLs to detect peptide–HLA complexes and be effectively activated. Although no empirical studies have attempted to address this issue in human trials, it appears that the very low expression level (i.e., even a single peptide–HLA protein/cell) seemed to be sufficient for activation of CTLs.41

4.3. Prediction of binding affinity to HLA molecules

Genetic variants must result in modified peptides that can be presented on HLA molecules in order to successfully elicit T‐cell responses. Different computational methods have been developed to predict peptide binding‐affinity to HLA molecules. The HLA class I molecules usually present 8‐11 amino‐acid peptides to cytotoxic CD8+ T‐lymphocytes where the N‐ and C‐termini are involved in HLA binding.42 Therefore, known HLA ligands of equal length can be served as predictive models for the binding affinity. Specific sequence motifs for the HLA binding can be identified by aligning to these known ligands using software including BIMAS. More accurate prediction approaches are based on artificial neural networks with predicted IC50. An example of such an approach is NetMHC,43, 44 which is one of the most commonly used and best validated prediction programs. These algorithms are trained using large datasets of peptide ligands such as those collected in the IEDB database;45 therefore, their prediction accuracy is higher for common HLA alleles than with many known ligands. A modified version of NetMHC, NetMHCpan, has been developed to predict peptides binding to alleles for which no ligands have been reported.46 Most algorithms are developed based on the prediction of the affinity of individual peptides to each HLA molecule. However, the affinity to the HLA molecules may not accurately represent the immunogenicity in individual patients, and it has been reported that peptide–HLA complex stability might have a better correlation with the immunogenicity of the peptides.47 Some computational methods, such as NetChop and NetCTL, focus on predicting antigen processing and peptide transport processes.48, 49 Structural‐based approaches are also important to predict the orientation of a mutated amino acid that is facing out of the HLA molecules to predict unnecessary cross‐reaction to a WT peptide. However, the individual parameter mentioned above has limited predictive values for immunogenicity in individual patients and a combination of these factors to predict neoantigens still remains as a big challenge to be addressed. Future developments may benefit from artificial intelligence or machine learning approaches with high‐throughput validation and larger datasets of cancer‐specific HLA ligands and T cell epitopes.

4.4. Experimental validation of neoantigen antigenicity

A large diversity of bioinformatics and biochemical tools are available to in silico predict, filter, or experimentally validate candidate peptides on the basis of their processing, HLA binding affinity, and stability. However, experimental validation of the immunogenicity of predicted potential neoantigens using patient's own T cells still remains as the final confirmation of their potential relevance. Recently, several methodologies were developed to interrogate patient's cellular immunity. These T cell‐based functional assays use either in silico predicted short peptides or tandem minigenes.50 As summarized in Table 1, there are several reports in which neoantigen‐specific T cells were successfully induced. We also developed a rapid pipeline to identify TCRs recognizing neoantigens.51 The process takes only approximately 2 weeks. It starts with peptide stimulation and ends with the identification of a TCRαβ pair(s), and established TCR‐engineered T cells with antigen‐specific cytotoxic activity. In 2016, a study found that mutation‐reactive T cells could be enriched from donor‐derived T cells and used as an effective therapy for the treatment of patients with metastatic cancer.52 However, only 1 in 5‐20 predicted neoantigens seems to activate antigen‐specific CTLs in cancer patients.

Table 1.

Summary of studies identifying neoantigen‐specific T cells

| Study | Type of cancer | Source | Methods | No. of patients | No. of tested (predicted) peptides | No. of detected T‐cell responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van Rooij et al., 201375 | Melanoma | TILs | pHLA multimer | 1 | (448) | 1 |

| Robbins et al., 201376 | Melanoma | TILs | ELISPOT | 3 | 227 (247) | 11 |

| Wick et al., 201477 | Ovarian cancer | TALs | ELISPOT | 2 | 114 | 1 |

| Rajasagi et al., 201478 | CLL | Patients’ PBMCs | ELISPOT | 2 | 48 | 3 |

| Lu et al., 201450 | Melanoma | TILs | ELISA | 2 | 288 | 2 |

| Snyder et al., 201413 | Melanoma | Patients’ PBMCs | Intracellular cytokine staining | 2 | – | 2 |

| Rizvi et al., 201514 | NSCLC | Patients’ PBMCs | pHLA multimer | 1 | (226) | 1 |

| Cohen et al., 201579 | Melanoma | TILs | pHLA multimer | 8 | 459 | 9 |

| Linnemann et al., 201580 | Melanoma | TILs | ELISA | 3 | 460 | 4 |

| Carreno et al., 201581 | Melanoma | Patients’ PBMCs | pHLA multimer | 3 | 21 | 6 |

| Kalaora et al., 201682 | Melanoma | TILs | pHLA multimer | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| McGranahan et al., 201683 | NSCLC | TILs | pHLA multimer | 2 | 642 | 3 |

| Stronen et al., 201684 | Melanoma | Donors’ PBMCs | pHLA multimer | 4 | 56 | 11 |

| Bassani‐Sternberg et al., 201657 | Melanoma | TILs | ELISPOT/pHLA multimer | 1 | 8 | 2 |

| Gros et al., 201685 | Melanoma | Patients’ PBMCs | ELISPOT | 4 | 691 | 7 |

| Bentzen et al., 201686 | NSCLC | TILs | pHLA multimer | 2 | 703 | 9 |

| Tran et al., 201687 | Gastrointestinal cancer | TILs | ELISPOT | 9 | 1273 | 18 |

| Kato et al.51 | Cell line, ovarian cancer | Donors’ PBMCs | pHLA multimer | 2 | 17 | 2 |

–, not available; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; ELISPOT, enzyme‐linked immunospot assay; NSCLC, non‐small‐cell lung cancer; pHLA, peptide–human leukocyte antigen; TAL, tumor‐associated lymphocyte; TIL, tumor‐infiltrating lymphocyte.

4.5. Immunopeptidome analysis

Due to the complexity of neoantigen prediction, often only a small fraction of the predicted neoantigens can be confirmed to be associated with neoantigen‐driven immune responses. One of the approaches to further narrow down the selected candidates is to assess whether the predicted peptides in fact bind to the HLA molecules using liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC‐MS/MS) analysis.53 The best‐established strategy to isolate peptides on the HLA is immunoaffinity purification of HLA–peptide complexes using pan‐anti‐HLA class I or class II antibodies. Typically, 108 to 109 cells are required for in‐depth immunopeptidome analysis, which will allow the identification of thousands of peptides presented on HLA molecules.54 Extremely high levels of sensitivity and accuracy of LC‐MS/MS analysis are required for detailed analysis of immunopeptidomes. The obtained MS/MS spectra will be compared to theoretical spectra of peptide sequences in databases using search engines like Mascot55 or MaxQuant56 to identify the HLA‐binding peptides. As inclusion of known mutations from repositories such TCGA or the COSMIC database may increase false positives, better personalized and customized reference databases based on whole‐exome and transcriptome sequencing information allow identification of private peptides that are not present in reference protein sequence databases. Unfortunately, although bioinformatic approaches and in‐depth analysis enable accurate identification of thousands of HLA peptides, only a few neoepitopes derived from predicted neoantigens have been identified. These results suggest a possible underdetection of neoantigens with post‐translational modifications or low levels of neoantigen expressions.57, 58 The HLA class II immunopeptidome has also been previously examined.54, 59, 60 Immunopeptidome analysis has a big advantage in identifying highly expressed neoepitopes on HLA molecules in cancer cells; however, enhanced assay sensitivity with improved bioinformatics analysis are critically essential to maximize the potential of immunopeptidome analysis for clinical application. It should be noted that functional assays will be definitely required to accompany immunopeptidome analyses in order to assess the immunogenicity of the identified neoantigens.

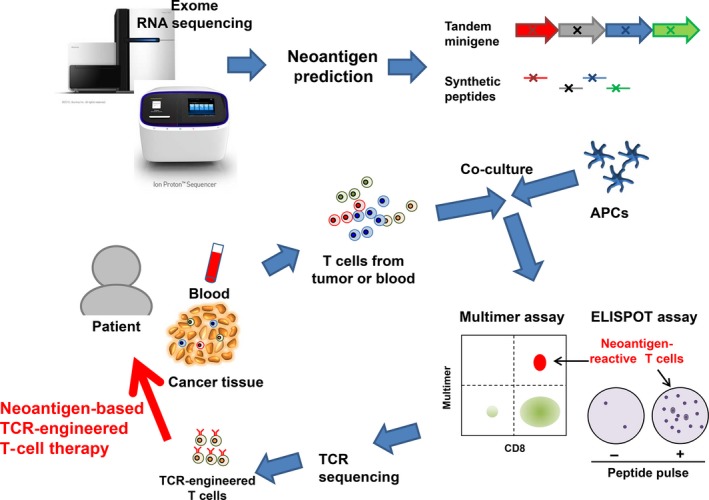

5. NEOANTIGEN‐BASED PERSONALIZED IMMUNOTHERAPY

Several approaches have been extensively studied in recent years to enhance CTL‐mediated antitumor immune responses in cancer immunotherapies (Figure 2). Cancer‐peptide vaccines targeting cancer‐specific neoantigens and shared antigens can activate or induce antigen‐specific CTLs in cancer patients. The immunogenicity of shared antigens has been established in many clinical studies, including ones reported by our group.61, 62, 63 As previously mentioned, neoantigens are immunogenic non‐self‐peptides that are generated by somatic mutations in cancer cells; therefore, they have attracted much attention as cancer cell‐specific antigens.64

Figure 2.

Workflow to screen neoantigen‐reactive T cells and develop T‐cell receptor (TCR)‐engineered T cells. For the neoantigen candidates from whole‐exome and RNA sequencing data, either tandem minigenes or peptides, including mutated amino acids, are synthesized. These peptides or minigenes can be expressed in patients’ autologous antigen‐presenting cells (APCs). Patients’ T cells are co‐cultured with these APCs to identify neoantigen‐reactive T cells using peptide–human leukocyte antigen multimer or enzyme‐linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays. The peptides specifically recognized by patients’ T cells will be used for neoantigen‐based cancer vaccine treatment. Sequencing of TCR in these neoantigen‐reactive T cells can identify a TCRαβ‐pair sequence, and this TCRαβ is expressed in patients’ T cells using a lentivirus vector system. These TCR‐modified T cells are then expanded in vitro and are re‐infused back into the patient as TCR‐engineered T‐cell therapy

Neoantigen‐specific T cells have already shown positive clinical results.65, 66 Recently, the results of 2 phase I clinical trials were reported that assessed a personalized neoantigen vaccine approach to treat patients with melanoma.67, 68 Both studies found that the vaccine treatment induced neoantigen‐specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and indicated potential benefits of neoantigen‐based vaccines. Ott et al.67 showed that 4 of 6 vaccinated patients had no recurrence at 25 months after the vaccination, and 2 patients with recurrent disease had complete regression by subsequent treatment with anti‐PD‐1 antibodies. Sahin et al.68 showed that 8 of 13 vaccinated patients mounted strong immune responses and remained recurrence‐free for 12‐23 months. Two of the remaining 5 patients with metastatic disease experienced vaccine‐related objective responses. These results indicate that neoantigen vaccines can be a promising treatment option to induce neoantigen‐specific T cells in cancer patients.

Furthermore, adoptive immunotherapies using TCR‐engineered T cells are being extensively studied as they have shown promising results in recent clinical trials.69 In this approach, identification of cancer antigen‐specific TCR and infusion therapy with TCR‐engineered T cells can induce very effective CTL‐mediated anticancer immunity, particularly for advanced tumors where the host immune system was extensively suppressed. The first adoptive T‐cell therapy with TCR‐engineered T cells was reported in 2006. The MART‐1 TCR‐modified lymphocytes successfully mediated tumor regression in humans.70 The NY‐ESO‐1‐specific TCR‐engineered T cells are the most thoroughly examined, and objective responses were observed in more than 50% of patients with synovial cell sarcoma, melanoma, and myeloma.71, 72 Currently, there is no published data on neoantigen‐specific TCR‐engineered T‐cell therapy in humans. However, preclinical studies have shown encouraging results where neoantigen‐specific TCR‐engineered T cells are also effective for large‐sized solid tumors.73, 74

6. CONCLUSION

Based on the results from research in recent years, it is plausible that neoantigens are a promising therapeutic target for T‐cell cancer immunotherapies. The tumor‐restricted expression of neoantigens highlights their specificity and potential safety in clinical settings. However, the key rate‐limiting factor for the progress of neoantigen‐specific T‐cell therapy is the insufficient accuracy of neoantigen prediction, including the HLA‐binding affinity, the immunogenicity of predicted peptides in individual cancer patients, and also the cross‐reactivity to WT peptides. Further studies are required to establish precise neoantigen prediction with efficient validity assays. In addition, accurate prediction in selecting the patient groups that may benefit from neoantigen‐targeted immunotherapies will further reduce the likelihood of unwanted adverse effects.

7. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Kiyotani K, Chan HT, Nakamura Y. Immunopharmacogenomics towards personalized cancer immunotherapy targeting neoantigens. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:542–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/cas.13498

REFERENCES

- 1. Erdag G, Schaefer JT, Smolkin ME, et al. Immunotype and immunohistologic characteristics of tumor‐infiltrating immune cells are associated with clinical outcome in metastatic melanoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1070‐1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez‐Cabo F, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960‐1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1974‐1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti‐PD‐1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443‐2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, et al. Safety and activity of anti‐PD‐L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455‐2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sharpe AH, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, Freeman GJ. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:239‐245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti‐PD‐1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell. 2016;165:35‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Inoue H, Park JH, Kiyotani K, et al. Intratumoral expression levels of PD‐L1, GZMA, and HLA‐A along with oligoclonal T cell expansion associate with response to nivolumab in metastatic melanoma. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5:e1204507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chowell D, Morris LGT, Grigg CM, et al. Patient HLA class I genotype influences cancer response to checkpoint blockade immunotherapy. Science. in press. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao4572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGranahan N, Rosenthal R, Hiley CT, et al. Allele‐specific HLA loss and immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Cell. 2017;171:1259‐1271 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olugbile S, Kiyotani K, Park J, et al. Early and sustained oligoclonal T cell expansion correlates with durable response to immune checkpoint blockade in lung cancer. J Cancer Sci Ther. 2017;9:717‐722. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haymaker CL, Kim D, Uemura M, et al. Metastatic melanoma patient had a complete response with clonal expansion after whole brain radiation and PD‐1 blockade. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:100‐105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA‐4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189‐2199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD‐1 blockade in non‐small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124‐128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA‐4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350:207‐211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD‐1 blockade in tumors with mismatch‐repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509‐2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69‐74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. De Plaen E, Lurquin C, Van Pel A, et al. Immunogenic (tum‐) variants of mouse tumor P815: cloning of the gene of tum‐ antigen P91A and identification of the tum‐ mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2274‐2278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Monach PA, Meredith SC, Siegel CT, Schreiber H. A unique tumor antigen produced by a single amino acid substitution. Immunity. 1995;2:45‐59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160:48‐61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brown SD, Warren RL, Gibb EA, et al. Neo‐antigens predicted by tumor genome meta‐analysis correlate with increased patient survival. Genome Res. 2014;24:743‐750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giannakis M, Mu XJ, Shukla SA, et al. Genomic correlates of immune‐cell infiltrates in colorectal carcinoma. Cell Rep. 2016;15:857‐865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Howitt BE, Shukla SA, Sholl LM, et al. Association of polymerase e‐mutated and microsatellite‐instable endometrial cancers with neoantigen load, number of tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes, and expression of PD‐1 and PD‐L1. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1319‐1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yap KL, Kiyotani K, Tamura K, et al. Whole‐exome sequencing of muscle‐invasive bladder cancer identifies recurrent mutations of UNC5C and prognostic importance of DNA repair gene mutations on survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:6605‐6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Choudhury NJ, Kiyotani K, Yap KL, et al. Low T‐cell receptor diversity, high somatic mutation burden, and high neoantigen load as predictors of clinical outcome in muscle‐invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol Focus. 2016;2:445‐452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kiyotani K, Park JH, Inoue H, et al. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and immune microenvironment in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1278330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kato T, Park JH, Kiyotani K, Ikeda Y, Miyoshi Y, Nakamura Y. Integrated analysis of somatic mutations and immune microenvironment of multiple regions in breast cancers. Oncotarget. 2017;8:62029‐62038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hundal J, Carreno BM, Petti AA, et al. pVAC‐Seq: A genome‐guided in silico approach to identifying tumor neoantigens. Genome Med. 2016;8:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang J, Mardis ER, Maher CA. INTEGRATE‐neo: a pipeline for personalized gene fusion neoantigen discovery. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:555‐557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou Z, Lyu X, Wu J, et al. TSNAD: an integrated software for cancer somatic mutation and tumour‐specific neoantigen detection. R Soc Open Sci. 2017;4:170050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Robinson J, Halliwell JA, Hayhurst JD, Flicek P, Parham P, Marsh SG. The IPD and IMGT/HLA database: allele variant databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D423‐D431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marsh SG, Albert ED, Bodmer WF, et al. Nomenclature for factors of the HLA system, 2010. Tissue Antigens. 2010;75:291‐455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szolek A, Schubert B, Mohr C, Sturm M, Feldhahn M, Kohlbacher O. OptiType: precision HLA typing from next‐generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3310‐3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shukla SA, Rooney MS, Rajasagi M, et al. Comprehensive analysis of cancer‐associated somatic mutations in class I HLA genes. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:1152‐1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bai Y, Ni M, Cooper B, Wei Y, Fury W. Inference of high resolution HLA types using genome‐wide RNA or DNA sequencing reads. BMC Genom. 2014;15:325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huang Y, Yang J, Ying D, et al. HLAreporter: a tool for HLA typing from next generation sequencing data. Genome Med. 2015;7:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim HJ, Pourmand N. HLA typing from RNA‐seq data using hierarchical read weighting [corrected]. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Warren RL, Choe G, Freeman DJ, et al. Derivation of HLA types from shotgun sequence datasets. Genome Med. 2012;4:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Boegel S, Lower M, Schafer M, et al. HLA typing from RNA‐Seq sequence reads. Genome Med. 2012;4:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kiyotani K, Mai TH, Nakamura Y. Comparison of exome‐based HLA class I genotyping tools: identification of platform‐specific genotyping errors. J Hum Genet. 2017;62:397‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sykulev Y, Joo M, Vturina I, Tsomides TJ, Eisen HN. Evidence that a single peptide‐MHC complex on a target cell can elicit a cytolytic T cell response. Immunity. 1996;4:565‐571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Leone P, Shin EC, Perosa F, Vacca A, Dammacco F, Racanelli V. MHC class I antigen processing and presenting machinery: organization, function, and defects in tumor cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1172‐1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Worning P, et al. Reliable prediction of T‐cell epitopes using neural networks with novel sequence representations. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1007‐1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, Buus S, Lund O, Nielsen M. NetMHC‐3.0: accurate web accessible predictions of human, mouse and monkey MHC class I affinities for peptides of length 8‐11. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W509‐W512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vita R, Overton JA, Greenbaum JA, et al. The immune epitope database (IEDB) 3.0. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D405‐D412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Blicher T, et al. NetMHCpan, a method for quantitative predictions of peptide binding to any HLA‐A and ‐B locus protein of known sequence. PLoS One. 2007;2:e796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Harndahl M, Rasmussen M, Roder G, et al. Peptide‐MHC class I stability is a better predictor than peptide affinity of CTL immunogenicity. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1405‐1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Lund O, Kesmir C. The role of the proteasome in generating cytotoxic T‐cell epitopes: insights obtained from improved predictions of proteasomal cleavage. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:33‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Larsen MV, Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, et al. An integrative approach to CTL epitope prediction: a combined algorithm integrating MHC class I binding, TAP transport efficiency, and proteasomal cleavage predictions. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2295‐2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lu YC, Yao X, Crystal JS, et al. Efficient identification of mutated cancer antigens recognized by T cells associated with durable tumor regressions. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:3401‐3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kato T, Matsuda T, Ikeda Y, et al. Effective screening of T cells recognizing neoantigens and construction of T‐cell receptor‐engineered T cells. Oncotarget. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Prickett TD, Crystal JS, Cohen CJ, et al. Durable complete response from metastatic melanoma after transfer of autologous T cells recognizing 10 mutated tumor antigens. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:669‐678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Caron E, Kowalewski DJ, Chiek Koh C, Sturm T, Schuster H, Aebersold R. Analysis of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) immunopeptidomes using mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:3105‐3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bassani‐Sternberg M, Pletscher‐Frankild S, Jensen LJ, Mann M. Mass spectrometry of human leukocyte antigen class I peptidomes reveals strong effects of protein abundance and turnover on antigen presentation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:658‐673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Perkins DN, Pappin DJ, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability‐based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551‐3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.‐range mass accuracies and proteome‐wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367‐1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bassani‐Sternberg M, Braunlein E, Klar R, et al. Direct identification of clinically relevant neoepitopes presented on native human melanoma tissue by mass spectrometry. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yadav M, Jhunjhunwala S, Phung QT, et al. Predicting immunogenic tumour mutations by combining mass spectrometry and exome sequencing. Nature. 2014;515:572‐576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hassan C, Kester MG, de Ru AH, et al. The human leukocyte antigen‐presented ligandome of B lymphocytes. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:1829‐1843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mommen GP, Marino F, Meiring HD, et al. Sampling from the proteome to the human leukocyte antigen‐DR (HLA‐DR) ligandome proceeds via high specificity. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:1412‐1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yoshitake Y, Fukuma D, Yuno A, et al. Phase II clinical trial of multiple peptide vaccination for advanced head and neck cancer patients revealed induction of immune responses and improved OS. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:312‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Okuno K, Sugiura F, Inoue K, Sukegawa Y. Clinical trial of a 7‐peptide cocktail vaccine with oral chemotherapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:3045‐3052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hazama S, Nakamura Y, Tanaka H, et al. A phase IotaI study of five peptides combination with oxaliplatin‐based chemotherapy as a first‐line therapy for advanced colorectal cancer (FXV study). J Transl Med. 2014;12:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Coulie PG, Van den Eynde BJ, van der Bruggen P, Boon T. Tumour antigens recognized by T lymphocytes: at the core of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:135‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tran E, Turcotte S, Gros A, et al. Cancer immunotherapy based on mutation‐specific CD4+ T cells in a patient with epithelial cancer. Science. 2014;344:641‐645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tran E, Robbins PF, Lu YC, et al. T‐cell transfer therapy targeting mutant KRAS in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2255‐2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ott PA, Hu Z, Keskin DB, et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature. 2017;547:217‐221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sahin U, Derhovanessian E, Miller M, et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly‐specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature. 2017;547:222‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Rosenberg SA, Restifo NP. Adoptive cell transfer as personalized immunotherapy for human cancer. Science. 2015;348:62‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, et al. Cancer regression in patients after transfer of genetically engineered lymphocytes. Science. 2006;314:126‐129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Robbins PF, Morgan RA, Feldman SA, et al. Tumor regression in patients with metastatic synovial cell sarcoma and melanoma using genetically engineered lymphocytes reactive with NY‐ESO‐1. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:917‐924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rapoport AP, Stadtmauer EA, Binder‐Scholl GK, et al. NY‐ESO‐1‐specific TCR‐engineered T cells mediate sustained antigen‐specific antitumor effects in myeloma. Nat Med. 2015;21:914‐921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Leisegang M, Engels B, Schreiber K, et al. Eradication of large solid tumors by gene therapy with a T‐cell receptor targeting a single cancer‐specific point mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2734‐2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Leisegang M, Kammertoens T, Uckert W, Blankenstein T. Targeting human melanoma neoantigens by T cell receptor gene therapy. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:854‐858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. van Rooij N, van Buuren MM, Philips D, et al. Tumor exome analysis reveals neoantigen‐specific T‐cell reactivity in an ipilimumab‐responsive melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e439‐e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Robbins PF, Lu YC, El‐Gamil M, et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor‐reactive T cells. Nat Med. 2013;19:747‐752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wick DA, Webb JR, Nielsen JS, et al. Surveillance of the tumor mutanome by T cells during progression from primary to recurrent ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1125‐1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rajasagi M, Shukla SA, Fritsch EF, et al. Systematic identification of personal tumor‐specific neoantigens in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:453‐462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cohen CJ, Gartner JJ, Horovitz‐Fried M, et al. Isolation of neoantigen‐specific T cells from tumor and peripheral lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:3981‐3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Linnemann C, van Buuren MM, Bies L, et al. High‐throughput epitope discovery reveals frequent recognition of neo‐antigens by CD4+ T cells in human melanoma. Nat Med. 2015;21:81‐85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Carreno BM, Magrini V, Becker‐Hapak M, et al. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen‐specific T cells. Science. 2015;348:803‐808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kalaora S, Barnea E, Merhavi‐Shoham E, et al. Use of HLA peptidomics and whole exome sequencing to identify human immunogenic neo‐antigens. Oncotarget. 2016;7:5110‐5117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. McGranahan N, Furness AJ, Rosenthal R, et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science. 2016;351:1463‐1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Stronen E, Toebes M, Kelderman S, et al. Targeting of cancer neoantigens with donor‐derived T cell receptor repertoires. Science. 2016;352:1337‐1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Gros A, Parkhurst MR, Tran E, et al. Prospective identification of neoantigen‐specific lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Nat Med. 2016;22:433‐438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Bentzen AK, Marquard AM, Lyngaa R, et al. Large‐scale detection of antigen‐specific T cells using peptide‐MHC‐I multimers labeled with DNA barcodes. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:1037‐1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Tran E, Ahmadzadeh M, Lu YC, et al. Immunogenicity of somatic mutations in human gastrointestinal cancers. Science. 2015;350:1387‐1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]