Abstract

Background

Many hospitalized older adults require family surrogates to make decisions, but surrogates may perceive that the quality of medical decisions is low and may have poor psychological outcomes after the patient’s hospitalization.

Objective

To determine the relationship between communication quality and high-quality medical decisions, psychological well-being, and satisfaction for surrogates of hospitalized older adults.

Design

Observational study at three hospitals in a Midwest metropolitan area.

Participants

Hospitalized older adults (65+ years) admitted to medicine and medical intensive care units who were unable to make medical decisions, and their family surrogates. Among 799 eligible dyads, 364 (45.6%) completed the study.

Main Measures

Communication was assessed during hospitalization using the information and emotional support subscales of the Family Inpatient Communication Survey. Decision quality was assessed with the Decisional Conflict Scale. Outcomes assessed at baseline and 4–6 weeks post-discharge included anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7), depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9), post-traumatic stress (Impact of Event Scale-Revised), and satisfaction (Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems).

Key Results

The mean patient age was 81.9 years (SD 8.32); 62% were women, and 28% African American. Among surrogates, 67% were adult children. Six to eight weeks post-discharge, 22.6% of surrogates reported anxiety (11.3% moderate–severe anxiety); 29% reported depression, (14.0% moderate–severe), and 14.6% had high levels of post-traumatic stress. Emotional support was associated with lower odds of anxiety (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.65, 95% CI 0.50, 0.85) and depression (AOR = 0.80, 95% CI 0.65, 0.99) at follow-up. In multivariable linear regression, emotional support was associated with lower post-traumatic stress (β = −0.30, p = 0.003) and higher decision quality (β = −0.44, p < 0.0001). Information was associated with higher post-traumatic stress (β = 0.23, p = 0.022) but also higher satisfaction (β = 0.61, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Emotional support of hospital surrogates is consistently associated with better psychological outcomes and decision quality, suggesting an opportunity to improve decision making and well-being.

KEY WORDS: proxy decision making, communication

INTRODUCTION

Nearly half of hospitalized older adults are unable to make their own medical decisions, and rely on surrogates—usually close family members—to make decisions for them.1 Surrogate decision makers face emotional, ethical, and communication challenges that differ from those in personal decision making. Surrogates suffer substantial psychological distress after hospitalization of a family member, particularly in the intensive care unit (ICU),2 – 5 yet we know little about the frequency or predictors of this distress. Given that over 13 million older adults are hospitalized each year, the magnitude of psychological distress from surrogate decision making and its impact on the care of patients and their surrogates needs further investigation.6

The content and quality of communication between surrogates and clinicians represent potentially modifiable factors that may impact the well-being of both patient and surrogate and the quality of medical decision making. Although research has shown that several types of interventions are effective in improving communication in the ICU setting,7 there are limited data on the aspects of the communication that are most important to surrogates or on outcomes of hospital communication outside the ICU. Qualitative studies have identified some aspects of communication that are important to surrogate decision makers, such as clinician availability, recommendations from providers, frequent information, and emotional support.8 , 9 Studies using direct observation in the ICU have found that the amount of time families are allowed to speak in ICU family meetings and expressions of empathy are associated with satisfaction.10 , 11 In the published literature, we found little data about the impact of communication quality on outcomes for hospital surrogate decision makers.

We propose that communication quality may affect both the quality of medical decision making and the psychological well-being of the surrogate.12 For this study, we specifically defined decision quality according to the framework developed for the Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS). The Effective Decision subscale of the DCS includes whether the decision is informed, is concordant with values, is a decision the surrogate plans to implement, and is one that the surrogate is satisfied with.13 In the present study, we hypothesize that surrogate ratings of communication quality in the hospital are associated with measures of decision quality and satisfaction and with the surrogate’s psychological well-being 6–8 weeks after hospitalization.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

The study was conducted in three hospitals in a single Midwest metropolitan area: a university tertiary referral hospital, an urban safety-net hospital, and a suburban community hospital affiliated with the university. We enrolled patient/surrogate dyads. Patients were adults 65 and older admitted to the internal medicine or medical ICU services of one of the three hospitals. Eligible surrogates had faced at least one of three types of decisions during the current hospital stay, regarding (1) life-sustaining therapy such as code status or use of a ventilator, (2) procedures or surgeries requiring written informed consent, or (3) placement in a nursing home or other facility. These decisions were selected based on prior research suggesting that they are both common and involve important judgments about the patient’s goals of care.9 Patients were excluded if they lacked a surrogate decision maker or could not complete surveys in English, or if the surrogate was a state-appointed guardian.

Measures

Communication quality was assessed using the Family Inpatient Communication Survey (http://medicine.iupui.edu/IUCAR/research/tools/FICS).14 The FICS is a 30-item scale completed by the surrogate decision maker to assess their perception of communication quality. It comprises two subscales, information and emotional support. Validation of the survey was conducted using the first 350 participants enrolled in the present study. Internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.94 for the information subscale and 0.90 for the emotional support subscale. We collected demographic information for the patient and surrogate based on surrogate report. Income was collected using income ranges and also by an item addressing whether the participant judged their income as “comfortable,” “just enough to make ends meet,” or “NOT enough to make ends meet.”15 This second item was used in further analyses due to high non-response to the income item.

Decision quality was assessed with the Effective Decision Subscale of the Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS), a well-validated measure of decision making.13 The subscale measures the four elements of decision quality: the decision is informed, is concordant with values, and is one that the surrogate plans to implement, and that the surrogate is satisfied with the decision.13 We modified the wording of items slightly so that questions were appropriate for persons making decisions for others. Overall psychological distress at baseline was assessed with the Kessler six-item Psychological Distress Scale.16 Post-traumatic stress was assessed with the Horowitz Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R),17 a measure used in prior studies of surrogate decision making.2 , 18 Anxiety was assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and depression was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9).19 Overall satisfaction was measured with a single item from the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Survey20 that rates the overall quality of the hospital stay on a scale from 0 to 10. Death at the time of the 6–8-week follow-up was determined by surrogate report.

Enrollment/Administration

Research assistants (RAs) identified potential eligible participants via medical record review of patient admissions. Reviews were conducted Monday through Friday during the study period. Patients were eliminated for reasons including lack of a family surrogate or evidence that the patient was making decisions independently. Among those with a potential need for a surrogate, the RA conducted a brief, 3–5-min screening telephone call with one of the patient’s physicians (intern or resident in teaching setting and attending; or nurse practitioner or attending physician for non-teaching services) between hospital days 2 and 4. Physician report was used to determine whether the patient required a surrogate for all decisions and whether the surrogate had been faced with a decision in at least one of the predetermined categories.

Informed consent and the enrollment interview were conducted in the hospital or by phone between hospital days 2 and 10. Surrogates consented for their own participation. Because the study involved patients who were entirely unable to make decisions, surrogate consent for the patient was obtained in all cases. Enrollment interviews included the DCS and the FICS. Because the DCS addresses specific medical decisions, this scale was administered to each surrogate for up to three specific decisions at enrollment and up to one additional decision at follow-up to account for any decisions that may have been missed between the enrollment interview and hospital discharge. Follow-up interviews at 6–8 weeks included the GAD-7, PHQ-9, IES-R, and satisfaction. This time frame was selected to minimize loss to follow-up, but to allow enough time for post-traumatic stress symptoms to develop, as these require a minimum of 1 month according to standard criteria.21

Data Analysis

We conducted separate regression analyses for each outcome. We used logistic regression models for the dichotomous outcomes of anxiety and depression, using published cutoffs for moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7 scores of 10+) and depression (PHQ-9 scores of 10+),19 and we report odds ratios. For continuous outcome variables, we used multivariable linear regression models using the Maximum Likelihood Robust (MLR) estimator for post-traumatic stress, satisfaction, and decisional conflict, and we report estimated standardized slope parameters. The MLR estimator is robust to skewed data. We chose to model post-traumatic stress as a continuous variable because this measure was designed as a symptom assessment rather than a diagnostic tool, and experts urge caution in the use of cutoff scores.17 , 22 However, to provide an overall estimate of the prevalence of serious post-traumatic stress symptoms, we provide an estimate of prevalence using a conservative cutoff score of 22+.23

For the information and emotional support subscales, we calculated a minimum important difference (MID), an estimate of the smallest change in an outcome that would be relevant to the responder. This was calculated using the standard error of measurement (SEM). The SEM was calculated as the standard deviation multiplied by the square root of 1 minus the reliability. Reliability was estimated with Cronbach’s alpha. The MID was defined as 1.0 SEM. The odds ratios reported from logistic regression were customized per one-MID-unit increase rather than the default one-point increase, because an MID indicates a more clinically relevant change.

For each adjusted analysis, we controlled for demographic variables (patient and surrogate age, education, race, and socioeconomic status). We used the socioeconomic item related to “comfort” with finances due to high non-response to the question assessing surrogate income. In order to account for the effect of baseline psychological distress on ratings of communication quality and the possibility of reverse causation (i.e., distress as a cause of poor communication), we controlled for baseline GAD-7 scores, PHQ-9 scores, and Kessler-6 scores (a general measure of psychological distress) in the regression models of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress, respectively. Because we hypothesized that the quality of decision making may be a factor in surrogate outcomes, we included the Effective Decision Subscale as a covariate. We also controlled for patient death between admission and 6–8-week follow-up due to presumed added stress of a death.

Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Mplus v7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). The Indiana University Institutional Review Board approved the study. Results are reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines.24

RESULTS

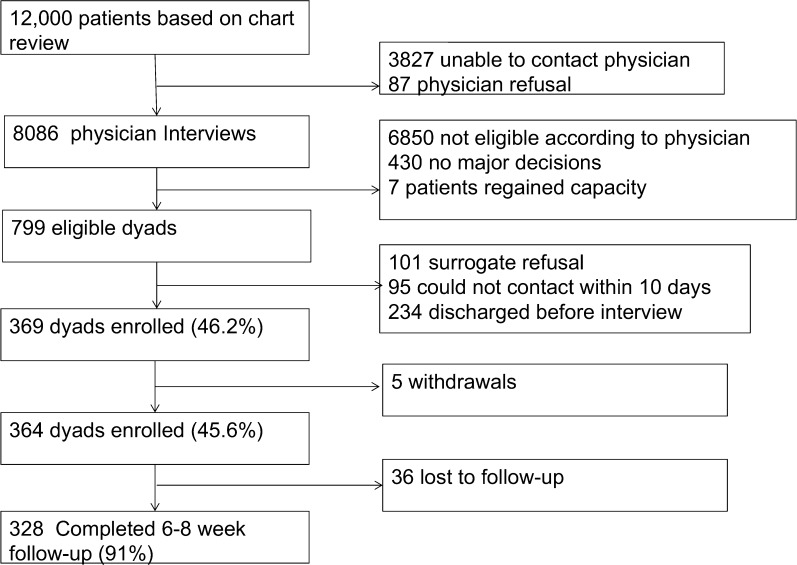

There were 12,000 potentially eligible patients identified via the electronic medical record (Fig. 1). Of these, RAs conducted screening interviews with the physicians of 8086 patients. The remainder of physicians could not be contacted within the enrollment window, and 87 physicians refused enrollment for the specific patient. Of the 8086, most were ineligible because the patients were making their own decisions. We identified 799 eligible patient/surrogate dyads, and enrolled 369 dyads. Five dyads withdrew, for a final enrollment of 364 dyads (45.6%). Enrolled patients had a mean age of 81.9 years; 61.5% were women, 69.0% white, and 27.8% African American (Table 1). The mean age of surrogates was 58.3 years; 70.9% were women. The majority of surrogates (66.8%) were the patients’ adult children; 16.8% were spouses. Baseline FICS information subscale scores ranged from 22 to 100 out of a potential 20–100, with a median of 82. Baseline FICS emotional subscale scores ranged from 12 to 60 out of a potential 12–60, with a median of 49. At baseline, 33.7% reported mild or greater anxiety and 13.8% reported clinically important (moderate or higher) anxiety; 40.1% reported at least mild depression and 14.7% reported moderate or high depression. A total of 328 (90.1%) of enrolled surrogates completed the 6–8-week follow-up survey. MIDs were calculated to be two points (i.e., 1 SEM) for the emotional subscale and three points for the informational subscale.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants: study enrollment and follow-up.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients and Surrogates (n = 364)

| Characteristic | Patients | Surrogates |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (standard deviation [SD]) | 81.9 (8.3) | 58.3 (11.2) |

| Education, mean (SD) | 12.2 (3.3) | 14.0 (2.5) |

| Sex: female | 224 (61.5) | 258 (70.9) |

| Race | ||

| African American/black | 101 (27.8) | 103 (28.3) |

| White | 251 (69.0) | 250 (68.7) |

| Asian | 4 (1.1) | 3 (0.8) |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Multi | 7 (1.9) | 6 (1.7) |

| Refused to answer | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Hispanic | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 116 (31.9) | 239 (65.7) |

| Single | 15 (4.1) | 53 (14.6) |

| Divorced | 53 (14.6) | 59 (16.2) |

| Widowed | 175 (48.1) | 9 (2.5) |

| Opposite-sex unmarried partner | 5 (1.4) | 4 (1.1) |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| None | 22 (6.0) | 17 (4.7) |

| Protestant | 288 (79.1) | 292 (80.2) |

| Catholic | 41 (11.3) | 38 (10.4) |

| Jewish | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Buddhist | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Hindu | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Muslim | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Orthodox Christian | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Native American | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) |

| Other | 4 (1.1) | 9 (2.5) |

| Do not know | 4 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Death during hospitalization | 20 (5.5) | |

| SES (comfort) | ||

| Comfortable | 203 (55.8) | |

| Just enough to make ends meet | 116 (31.9) | |

| Not enough to make ends meet | 40 (11.0) | |

| Refused to answer | 3 (0.8) | |

| Do not know | 2 (0.6) | |

| Income category | ||

| ≤ $24,999 | 72 (19.8) | |

| $25,000–49,999 | 97 (26.7) | |

| $50,000–74,999 | 81 (22.3) | |

| $75,000–99,999 | 31 (8.5) | |

| ≥ $100,000 | 45 (12.4) | |

| Not determined | 5 (1.4) | |

| Refused to answer | 33 (9.1) | |

| Relationship to patient | ||

| Spouse | 61 (16.8) | |

| Spouse equivalent/unmarried partner | 1 (0.3) | |

| Son/daughter | 243 (66.8) | |

| Son/daughter-in-law | 10 (2.8) | |

| Grandchild | 9 (2.5) | |

| Neighbor/friend | 2 (0.6) | |

| Other | 38 (10.4) | |

| Decisions during hospitalization | ||

| Life-sustaining treatment | 223 (61.3) | |

| Procedures and surgeries | 171 (47.0) | |

| Post-discharge placement | 205 (56.3) | |

| ICU stay during hospitalization | 94 (26.0) | |

Abbreviations: SES, socioeconomic status; ICU, intensive care unit

Psychological Outcomes

At follow-up, 22.6% of surrogates reported at least mild anxiety and 11.3% reported moderate–severe anxiety; 29% reported at least mild depression and 14.0% reported moderate–severe depression (Table 2). Scores for ICU surrogates were not significantly different from those on non-ICU services (8.3% of ICU surrogates had moderate or greater anxiety vs. 12.5% of non-ICU surrogates, p = 0.2778; 14.6% of ICU surrogates had moderate or greater depression vs. 13.8% in the non-ICU group, p = 0.8512). Post-traumatic stress scores ranged from 0 to 80, with a median of 3.5, and 14.6% of participants reported a high score. Median scores were higher in the ICU than non-ICU surrogates (4.5 [0–79] vs. 2 [0–80], p = 0.0154). Satisfaction scores ranged from 0 to 10, with a median of 9. We examined differences in the outcome variables based on the decisions faced by each surrogate and found no differences for anxiety, depression, decision quality, or post-traumatic stress. Those with decisions regarding life-sustaining treatment had slightly higher satisfaction scores (median 9 [0–10] vs. 8.5 [3–10], p = 0.0002).

Table 2.

Outcome Measures

| Measure* | Baseline (N = 364) | Follow-up (N = 328) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity, n (%) | Median (range) | Severity, n (%) | Median (range) | ||

| Anxiety | GAD-7 | 2.5 (0–21) | 1 (0–21) | ||

| Minimal (0–4) | 240 (66.3) | 254 (77.4) | |||

| Mild (5–9) | 72 (19.9) | 37 (11.3) | |||

| Moderate (10–14) | 25 (6.9) | 23 (7.0) | |||

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 21 (5.8) | 11 (3.4) | |||

| Severe (20+) | 4 (1.1) | 3 (0.9) | |||

| Depression | PHQ-9 | 3 (0–24) | 2 (0–25) | ||

| Minimal (0–4) | 217 (59.9) | 233 (71.0) | |||

| Mild (5–9) | 92 (25.4) | 49 (14.9) | |||

| Moderate (10–14) | 31 (8.6) | 27 (8.2) | |||

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 10 (2.8) | 13 (4.0) | |||

| Severe (20+) | 12 (3.3) | 6 (1.8) | |||

| Post-traumatic stress | IES-R | 48 (14.6) | 3.5 (0–80) | ||

| General distress | Kessler-6 | 2 (0–23) | |||

| Decision effectiveness | DCS Effective Decision Subscale | 25 (0–87.5) | 6.25 (0–50) | ||

| Satisfaction | HCAHPS | 9 (0–10) | |||

*High scores on the Generalized Anxiety-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 are 10 and above and on the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) are 22 and above

In unadjusted analysis, the MID on the emotional support subscale (odds ratio [OR] = 0.84, 95% CI 0.76, 0.94, p = 0.0015), but not the information subscale (OR = 0.95 [0.88, 1.01], p = 0.1039), was associated with lower odds of moderate–severe anxiety at follow-up (Table 3). These results persisted when controlling for demographics, baseline anxiety, decision quality, and patient death (emotional support adjusted OR [AOR] = 0.65 [0.50, 0.85], p = 0.0018; information AOR = 1.19 [0.99, 1.42], p = 0.0646). Similarly, the odds of depression were associated with emotional support in unadjusted (OR = 0.89 [0.81, 0.97], p = 0.0117) and adjusted models (AOR = 0.80 [0.65, 0.99], p = 0.0396). Information was not associated with depression (unadjusted OR = 0.96, p = 0.2488; AOR = 1.08, p = 0.3072).

Table 3.

Association Between Communication and Surrogate-Rated Outcomes

| Odds ratios* (95% CI) from logistic regression models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | |||

| Univariate models† | Adjusted model † | Univariate models† | Adjusted model† | |

| Information | 0.95 (0.88, 1.01); p = 0.1039 | 1.19 (0.99, 1.42); p = 0.0646 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03); p = 0.2488 | 1.08 (0.93, 1.26); p = 0.3072 |

| Emotional support | 0.84 (0.76, 0.94); p = 0.0015 | 0.65 (0.50, 0.85); p = 0.0018 | 0.89 (0.81, 0.97); p = 0.0117 | 0.80 (0.65, 0.99); p = 0.0396 |

| White | 4.56 (1.25, 16.55); p = 0.0212 | 2.22 (0.84, 5.86); p = 0.1064 | ||

| Age (patient) | 0.98 (0.92, 1.04); p = 0.4541 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03); p = 0.3923 | ||

| Age (surrogate) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04); p = 0.7578 | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03); p = 0.6630 | ||

| Education (patient) | 1.09 (0.93, 1.28); p = 0.3093 | 1.04 (0.90, 1.19); p = 0.5896 | ||

| Education (surrogate) | 0.96 (0.75, 1.23); p = 0.7479 | 0.96 (0.78, 1.18); p = 0.6996 | ||

| SES (comfortable) | 0.59 (0.13, 2.61); p = 0.4848 | 0.33 (0.11, 1.05); p = 0.0607 | ||

| SES (just enough) | 0.64 (0.14, 2.91); p = 0.5612 | 0.37 (0.12, 1.19); p = 0.0953 | ||

| Decision effectiveness | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04); p = 0.9174 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03); p = 0.8331 | ||

| Death | 1.40 (0.47, 4.21); p = 0.5508 | 4.07 (1.72, 9.64); p = 0.0014 | ||

| Outcome at baseline‡ | 1.31 (1.20, 1.43); p < 0.0001 | 1.19 (1.11, 1.28); p < 0.0001 | ||

*Odds ratios for information and emotional support are per the minimal important difference, which is a three-point change in informational and a two-point change in emotional support

†Univariate models consist of separate analyses, with each subscale entered individually as the independent variables. Adjusted models include covariates, with parameter estimates given. High scores on the Generalized Anxiety-7 (GAD-7) and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 are 10 and above

‡Outcome at baseline is the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 for anxiety, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression

In MLR-estimated linear regression analyses, emotional support was associated with lower post-traumatic stress scores (β = −0.13, p = 0.0137), while information was not (β = −0.04, p = 0.4411; Table 4). Emotional support remained significantly associated with post-traumatic stress when adjusted for covariates (β = −0.30, p = 0.0034. The information subscale was associated with higher post-traumatic stress scores in adjusted analysis. (β = 0.23, p = 0.0221).

Table 4.

Association Between Communication and Surrogate-Rated Outcomes: Standardized Coefficients from Linear Regression Models

| Multivariable linear regression with Maximum Likelihood Robust to Skewness (MLR) estimator* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-traumatic stress | Satisfaction | Decision quality† | ||||

| Univariate models‡ | Adjusted model‡ | Univariate models‡ | Adjusted model‡ | Univariate models‡ | Adjusted model‡ | |

| Information | −0.04; p = 0.4411 | 0.23; p = 0.0221 | 0.58; p < 0.0001 | 0.61; p < 0.0001 | −0.44; p < 0.0001 | −0.14; p = 0.1461 |

| Emotional support | −0.13; p = 0.0137 | −0.30; p = 0.0034 | 0.47; p < 0.0001 | −0.01; p = 0.9182 | −0.56; p < 0.0001 | −0.44; p < 0.0001 |

| White | −0.15; p = 0.0154 | −0.03; p = 0.6000 | 0.08; p = 0.1861 | |||

| Age (patient) | −0.13; p = 0.0329 | 0.02; p = 0.7699 | −0.06; p = 0.3561 | |||

| Age (surrogate) | −0.02; p = 0.6988 | 0.12; p = 0.0703 | −0.00; p = 0.9437 | |||

| Education (patient) | −0.02; p = 0.7860 | 0.02; p = 0.8163 | 0.02; p = 0.7816 | |||

| Education (surrogate) | 0.02; p = 0.7350 | −0.20; p = 0.0029 | −0.03; p = 0.7035 | |||

| SES (comfortable vs. not enough) | −0.02; p = 0.8658 | 0.11; p = 0.2870 | 0.06; p = 0.5621 | |||

| SES (just enough vs. not enough) | −0.06; p = 0.5545 | 0.04; p = 0.6828 | 0.09; p = 0.3286 | |||

| Decision effectiveness | 0.07; p = 0.2964 | 0.00; p = 0.9715 | – | |||

| Death | 0.25; p < 0.0001 | −0.04; p = 0.5143 | −0.00; p = 0.9345 | |||

| Stress at baseline§ | 0.41; p < 0.0001 | – | – | |||

*Slope coefficients for information and emotional support are per the minimal important difference, which is a three-point change in informational and a two-point change in emotional support

†For each surrogate, we selected the decision with the highest score

‡Univariate models consist of separate analyses, with each subscale entered individually as the independent variables. Adjusted models include covariates, with parameter estimates given. High scores on the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) are 22 and above

§Stress at baseline measured by the Kessler-6

Other Outcomes

In unadjusted analysis, satisfaction was associated with both emotional support (β = 0.47 p < 0.0001) and information (β = 0.58, p < 0.0001); in adjusted models, only information remained significant (β = 0.61 p < 0.0001). Surrogate ratings of decision quality were associated with emotional support but not information (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This observational study revealed high levels of psychological distress during the patient’s acute illness. Additionally, 11–15% of surrogate decision makers for hospitalized older adults suffered from clinically high levels of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress 6–8 weeks after hospitalization. The decline in the frequency of symptoms suggests that some of the distress experienced during the acute illness resolves, but stress remains for over 10% of surrogates. Our results are consistent with prior literature establishing substantial degrees of distress among surrogate decision makers.3 In the ICU setting, this phenomenon has been labeled post-intensive care syndrome—family.4 We extend these results beyond the ICU; our finding that anxiety and depression were not significantly higher in the ICU suggests that surrogates for older adults are at risk of psychological distress in other hospital settings, and thus many more family members are at risk than previously thought.

Further, surrogates’ perception of emotional support during hospitalization was associated with lower anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, and decision quality 6–8 weeks later. This effect was particularly strong for anxiety, with a 54% increase in the odds of anxiety for every two-point decrease in emotional support (i.e., 1/0.65 = 1.54), after adjusting for other covariates. Information was associated with better satisfaction but increased post-traumatic stress.

Although an observational study cannot prove causation, our results raise the question of whether improved emotional support could lead to both better decisions for the patient and better psychological outcomes. Surrogate–provider communication interventions that include emotional support hold promise for improving surrogate outcomes. Helping clinicians develop and utilize empathic communication skills may be especially important. Educational interventions such as VITALtalk (www.vitaltalk.org) and communication interventions that include recognition of emotion and expressions of empathy are likely to be most effective in reducing surrogate distress.25 Future randomized trials are needed to assess the impact of these specific approaches on surrogate outcomes. Strategies may be needed to overcome other barriers to empathic communication in the clinical setting, such as time pressures or worry that empathy will open a “Pandora’s box” of emotions.26 , 27 As the population ages, and an increasing number of family members find themselves in the role of surrogate, providing appropriate support for family members will become a public health imperative.

A surprising finding was that when controlling for emotional support, informational support was positively associated with greater post-traumatic stress. Prior randomized controlled trials of ICU support interventions have found mixed results, with one recent study noting that information support actually contributed to increased post-traumatic stress.18 , 28 , 29 Our results may help explain this discrepancy; intensive emotional support may be needed to mitigate the stress of receiving prognostic information about life-threatening illness. This finding might seem to conflict with guidance toward fully informing patients and families in order to enable high-quality decision making. However, while high-quality information is important to patients and family members, it may have negative consequences if not accompanied by appropriate emotional support.

In contrast, high-quality information was associated with higher overall satisfaction with the hospital stay, which may be of particular interest to both clinicians and hospital administrators. Although surrogate decision makers of adult patients are not included in standard adult HCAHPS surveys,30 it is quite possible that they fill them out on behalf of the patient. Families of cognitively impaired patients have important insights into the quality of decision making and care, and communication appears to be one important factor in their assessment.

One limitation of the current study is the possibility of reverse causation, that is, patients with greater psychological distress at baseline might have rated communication less favorably. We attempted to account for this by administering several outcome measures including anxiety and depression at both baseline and 6–8-week follow-up, and controlling for baseline distress in each analysis. We also controlled for covariates that may have affected both communication and psychological outcomes, such as whether the patient died. Future research—for example, a randomized trial of a communication intervention—will be important for further testing the causal relationship between communication and outcomes. A second limitation is the setting in a single metropolitan area, which may not generalize to other locations. There also may have been some bias, because we were only able to enroll 45.6% of eligible surrogates. We also made slight modifications to the DCS in order to administer this to surrogates instead of patients, which may have affected the scale’s validity. Finally, although our sample was highly diverse in age, education, and race (African American and white), we lacked the perspectives of Asian and Latino populations.

In conclusion, the relationship between communication quality and outcomes for the surrogate is complex and multifaceted. Our finding that emotional support of hospital surrogates is associated with reduced anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms suggests that it is not enough to simply provide good information: family members also need emotional support when making difficult decisions. Even though high-quality information is associated with overall satisfaction with the hospital stay, information without emotional support may be harmful to surrogates. Interventions that improve the communication experiences of surrogates must address both dimensions.

Funding

This study was funded by the Research in Palliative and End-of Life Communication and Training (RESPECT) Center, Indiana University—Purdue University Indianapolis, and The National Institute on Aging (R01 AG044408).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Torke AM, Sachs GA, Helft PR, et al. Scope and outcomes of surrogate decision making among hospitalized older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):370–377. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987–994. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic Review: The effects on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:336–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome–family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:618–624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron JI, Chu LM, Matte A, et al. One-Year Outcomes in Caregivers of Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(19):1831–1841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1511160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Hospital Discharge Survey. 2010; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/hospital.htm. Accessed October 26 2017.

- 7.Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, Carson SS, Hanson LC. Randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care. Chest. 2011;139:543–554. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vig EK, Starks H, Taylor JS, Hopley EK, Fryer-Edwards K. Surviving surrogate decision-making: what helps and hampers the experience of making medical decisions for others. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1274–1279. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torke AM, Petronio S, Purnell C, Sachs GA, Helft PR, Callahan CM. Communicating with Clinicians: A Study of Surrogates for Hospitalized Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1401–1407. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonagh JR, Elliott TB, Engelberg RA, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1484–1488. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selph RB, Shiang J, Engelberg R, Curtis JR, White DB. Empathy and life support decisions in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1311–1317. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0643-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torke AM, Petronio S, Sachs GA, Helft PR, Purnell C. A conceptual model of the role of communication in surrogate decision making for hospitalized adults. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Connor AM. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale. Med Dec Making. 1995;15:25. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torke AM, Monahan P, Callahan CM, et al. Validation of the Family Inpatient Communication Survey. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;53:96–108.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Nauser JA, Bakas T, Welch JL. A new instrument to measure quality of life of heart failure family caregivers. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26(1):53–64. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181e4a313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific pscyhological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/S0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of events scale: A measure of subjective distress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU [see comment] N Eng J Med. 2007;356(5):469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345–359. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darby C, Hays RD, Kletke P. Development and evaluation of the CAHPS survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:1973–1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00490.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creamer M, Bell R, Failla S. Psychometric properties of the Impact of Event Scale—Revised. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:1489–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rash CJ, Coffey SF, Baschnagel JS, Drobes DJ, Saladin ME. Psychometric properties of the IES-R in traumatized substance dependent individuals with and without PTSD. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1039–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol.. 2006;61:344–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134(4):835–843. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halpern J. From Detached Concern to Empathy: Humanizing Medical Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hardee JT, Platt FW. Exploring and overcoming barriers to clinical empathic communication. J Commun Healthc. 2010;3:17–23. doi: 10.1179/cih.2010.3.1.17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Randomized Trial of Communication Facilitators to Reduce Family Distress and Intensity of End-of-life Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Carson SS, Cox CE, Wallenstein S, et al. Effect of Palliative Care-Led Meetings for Families of Patients With Chronic Critical Illness: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316(1):51–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.HCAHPS: Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. http://www.hcahpsonline.org/home.aspx. Accessed October 26 2017.