Abstract

Immune checkpoint blockade antibodies are setting a new standard of care for cancer patients. It is therefore important to assess any new immune-based therapies in the context of immune checkpoint blockade. Here, we evaluate the impact of combining a synthetic consensus TERT DNA vaccine that has improved capacity to break tolerance with immune checkpoint inhibitors. We observed that blockade of CTLA-4 or, to a lesser extent, PD-1 synergized with TERT vaccine, generating more robust anti-tumor activity compared to checkpoint alone or vaccine alone. Despite this anti-tumor synergy, none of these immune checkpoint therapies showed improvement in TERT antigen-specific immune responses in tumor-bearing mice. αCTLA-4 therapy enhanced the frequency of T-bet+/CD44+ effector CD8+ T cells within the tumor and decreased the frequency of regulatory T cells within the tumor, but not in peripheral blood. CTLA-4 blockade synergized more than Treg depletion with TERT DNA vaccine, suggesting that the effect of CTLA-4 blockade is more likely due to the expansion of effector T cells in the tumor rather than a reduction in the frequency of Tregs. These results suggest that immune checkpoint inhibitors function to alter the immune regulatory environment to synergize with DNA vaccines, rather than boosting antigen-specific responses at the site of vaccination.

Keywords: CTLA4, DNA vaccine, immune tolerance, PD1, TERT

In this issue of Molecular Therapy, Duperret et al. show synergy of DNA vaccines with immune checkpoint blockade antibodies targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1 in reducing tumor burden in mice. Importantly, these antibodies did not boost systemic immune responses and instead altered immune activation in the tumor.

Introduction

The magnitude of an adaptive immune response to a foreign antigen is determined not only by the strength of interaction between the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and the T cell receptor (TCR) but also by co-stimulation at the immunological synapse.1 Without co-stimulation, T cells will fail to initiate an effective immune response. Additional co-stimulatory molecules or immune checkpoint molecules exist to control the amplitude of T cell activation to prevent autoimmune responses. These immune checkpoints (CTLA-4, PD-1, LAG3, and TIM3) are often necessary for initiation of an immune response; however, as antigen persists, these checkpoints ultimately serve to dampen the T cell effector function against the foreign antigen.2 CTLA-4, PD-1, LAG3, and TIM3 are all expressed on T cells and limit T cell effector activity. Antibodies blocking these molecules have been shown to augment the effector activity of tumor-specific T cells and additionally inhibit regulatory T cell (Treg) activity and reduce tumor burden in preclinical models and/or in clinical trials as mono-therapies.3, 4, 5

In particular, blockade of the immune inhibitory checkpoints PD-1 or CTLA-4 has shown promising results in the clinic for dozens of tumor types, and PD-1 blockade has become a standard of care for melanoma and non-small-cell lung cancer.6, 7, 8 However, response rates to these mono-therapies are relatively low (33.7% response for pembrolizumab [α-PD-1] and 11.9% response for ipilimumab [α-CTLA-4] in melanoma patients), leaving room for improvement.9 The lack of response for the majority of such patients may be due to a lack of pre-existing tumor-associated T cell responses. Strategies to combine PD-1 or CTLA-4 blockade with therapies that prime T cells, such as radiation or irradiated cell-based vaccines, have shown improvements in pre-clinical models or in clinical trials.5, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 These approaches, however, may rely on T cell responses to neo-antigens within the tumor.18, 19 Enhanced T cell priming by vaccines may therefore be required to break tolerance to self-antigens for patients with poor response to immune checkpoint blockade. However, the mechanistic interactions between immune checkpoint blockade antibodies and vaccines are poorly understood.

Therapeutic peptide or DNA vaccination represents a more targeted approach for directing T cells toward specific, less variable tumor-associated antigens (TAAs). In mouse models, peptide vaccines have been shown to synergize with immune checkpoint blockade.20, 21 However, peptide vaccines are histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA) restricted and therefore cannot be used for all patients. Unlike peptide vaccines, synthetic DNA (synDNA) vaccines are not HLA restricted, are robustly presented on both MHC class I and MHC class II, and can be designed using consensus sequences in order to break tolerance.22

Our laboratory has pioneered efforts to develop therapeutic DNA vaccines for patients with human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3).23, 24 We incorporated important improvements to the DNA vaccine platform, such as plasmid optimization and use of in vivo electroporation, which has directly led to enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses.24, 25, 26 These improvements led to the first DNA vaccine to demonstrate potent immune responses and anti-neoplastic activity in a human clinical trial.23, 24 Specifically, a synthetic DNA vaccine targeting HPV-16 and HPV-18 E6 and E7 proteins (VGX-3100) showed clinical efficacy for therapeutic treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3 (CIN2/3) in women in a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb clinical trial.23

Next, we focused on developing a novel DNA vaccine platform to help break tolerance to non-viral tumor-associated antigens, such as TERT and WT-1.27, 28 This novel platform is based on the concept that the introduction of xenogeneic antigens into mice can induce autoimmunity.29, 30 We developed a synthetic consensus (SynCon) approach in which gene sequences from various species are compared to identify a consensus sequence (with approximately 95% homology to the native gene sequence), an approach that has enhanced the capacity to break tolerance, yet maintains T cell killing against native MHC class I-presented sequences. We reported that this synthetic consensus vaccine design strategy is superior to native DNA-vaccine-encoded antigens for the WT-1 antigen.28

Here, we sought to further improve synthetic consensus DNA vaccine immune responses through combination therapy with immune checkpoint blockade. We utilized a SynCon mouse TERT DNA vaccine with enhanced capacity to break tolerance in combination with antibodies that block the immune checkpoint molecules CTLA-4 or PD-1. We chose to test this combination therapy in the TC-1 tumor model, which does not respond to immune checkpoint blockade alone. We observe that blockade of CTLA-4, PD-1, or a combination of the two effectively synergized with SynCon TERT DNA vaccine to slow tumor growth in mice. However, peripheral and systemic immune responses did not necessarily correspond with anti-tumor activity of immune therapy combinations. These studies highlight the potential application of these DNA vaccine/immune checkpoint blockade combinations in patients that respond poorly to immune checkpoint blockade alone and allow for better rational design of combination therapies. Furthermore, these results suggest that this synergistic effect is due to the effect of immune checkpoint blockade on expanding effector T cells in the tumor microenvironment rather than boosting vaccine responses in the periphery.

Results

CTLA-4 and PD-1 Blockade Synergizes with mTERT DNA Vaccine in Generating Anti-tumor Immunity

For these studies, we utilized a synthetic consensus (SynCon) mouse TERT DNA vaccine. This vaccine administered alone exhibits a robust capacity to generate an immune response against matched, SynCon peptides, while maintaining the capacity to break tolerance to native mouse TERT peptides in C57BL/6 mice (Figures S1A and S1B). For the remaining experiments, we focused on antigen-specific immune responses targeting native mouse TERT peptides. In addition, this SynCon mouse TERT DNA vaccine is capable of slowing tumor growth and prolonging survival in a proportion of the mice in a TC-1 mouse tumor challenge model (Figures S2A and S2B).

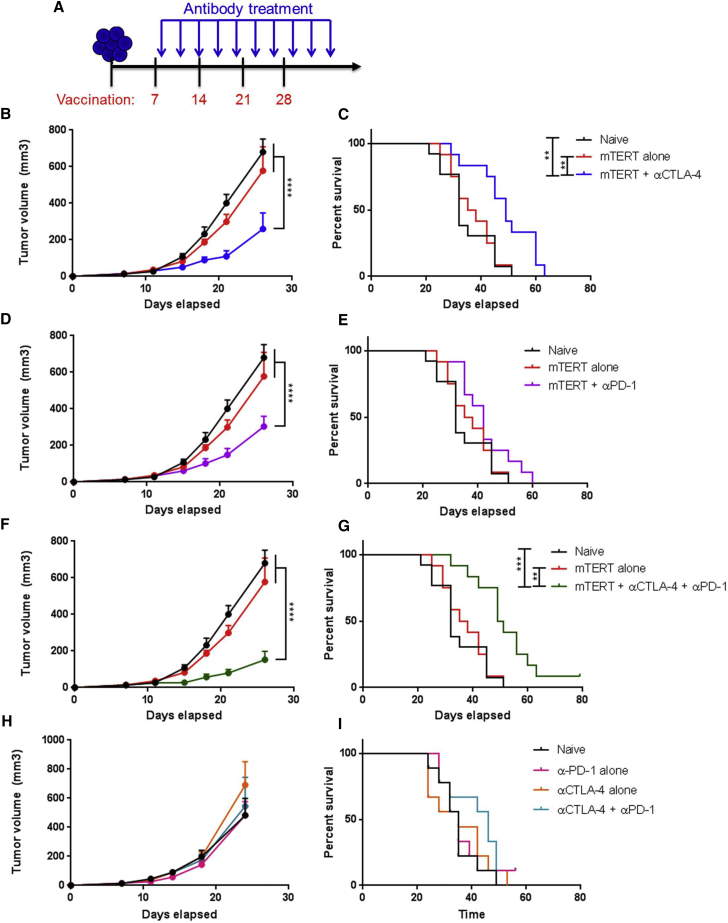

We first examined whether αCTLA-4 or αPD-1 therapy would improve anti-tumor activity in a therapeutic tumor challenge setting. We implanted mice with TC-1 tumors and initiated immunizations after palpable tumors formed 1 week following implantation (Figure 1A). Mice were immunized at 1-week intervals for a total of four immunizations. Checkpoint treatment began 1 day following the first immunization and continued until 1 week following the final immunization (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Delivery of αCTLA-4 or αPD-1 Post-first Vaccination Synergizes with TERT DNA Vaccine above Checkpoint Alone in Generating Anti-tumor Immune Response

(A) Experimental setup. Mice were implanted with TC-1 tumor cells on day 0 and then immunized four times at 1-week intervals starting 7 days after tumor implant. Mice were given antibodies (200 μg per mouse) every 3 days starting 1 day after the first immunization. Antibody delivery was continued until 1 week after the final vaccination. (B, D, F, and H) Tumor volume measurements over time for naive mice, mTERT vaccine-treated mice, or mice treated with mTERT vaccine plus αCTLA-4 (B), αPD-1 (D), or a combination of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 (F). (C, E, and G) Mouse survival over time for naive mice, mTERT vaccine-treated mice, or mice treated with mTERT vaccine plus αCTLA-4 (C), αPD-1 (D), or a combination of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 (G). For (B)–(G), n = 12–13 mice per group. (H) Tumor volume measurements over time for naive mice unvaccinated mice treated with αPD-1, αCTLA-4, or both αPD-1 and αCTLA-4. (I) Mouse survival over time for naive mice or unvaccinated mice treated with αPD-1, αCTLA-4, or both αPD-1 and αCTLA-4. Mice were euthanized if they appeared sick or if the tumor diameter exceeded 1.5 cm. For (H) and (I), n = 9 mice per groiup. Each experiment was repeated at least once to verify results. Significance for tumor volume measurements was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. Significance for mouse survival was determined by the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Error bars indicate ± SEM.

We observed that both α-CTLA-4 and α-PD-1 therapies synergized with mTERT DNA immunization above vaccine therapy alone in a therapeutic TC-1 tumor challenge model when immune checkpoints were delivered 1 day post-first immunization (Figures 1B–1G). Both α-CTLA-4 and α-PD-1 therapy alone had no initial impact in slowing tumor growth and no significant impact on mouse survival (Figures 1H and 1I). SynCon mTERT immunization alone slightly slowed tumor growth and improved survival compared to naive mice. However, α-CTLA-4 and α-PD-1 in combination with SynCon mTERT robustly slowed tumor growth and significantly improved survival compared to DNA alone or naive mice (Figures 1B–1E). Synergy was greater for α-CTLA-4, in particular for survival, compared to α-PD-1 (Figures 1B–1E).

Combination therapy of αCTLA-4 and α-PD-1 in both animal models and in the clinic has shown improved anti-tumor responses compared to treatment with each checkpoint alone.33, 34, 35 In particular, combination therapy with αCTLA-4 and α-PD-1 was reported to improve the anti-tumor immunity of cell-based vaccines.5, 17 We therefore examined whether a triple-combination therapy with αCTLA-4, α-PD-1, and SynCon mTERT could further improve therapeutic anti-tumor activity. We observed that combination therapy of SynCon mTERT with both αCTLA-4 and α-PD-1 slightly improved anti-tumor activity and survival of mice. This effect was greater than the combined treatment of αCTLA-4 and SynCon mTERT (Figures 1F and 1G). The combination therapy alone without the DNA vaccine exhibited little impact on tumor growth or on mouse survival (Figures 1H and 1I).

Impact of Immune Checkpoint Blockade on Systemic Immune Responses in Tumor-Bearing Mice

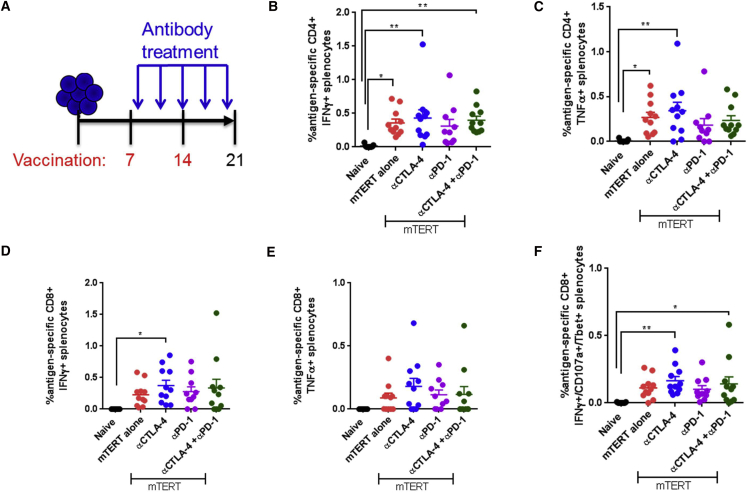

Next, we explored immune responses in tumor-bearing mice treated with combination vaccine and the αCTLA-4/αPD-1 immune checkpoint blockade antibody therapy. We implanted mice with TC-1 tumors, immunized mice on days 7 and 14, and sacrificed mice on day 21 (Figure 2A). Checkpoint inhibitor delivery was initiated one day following the first immunization, and continued every 3 days until day 21 (Figure 2A). We examined the antigen-specific immune responses in the spleen and the exhaustion marker PD-1 in the periphery and in spleen.

Figure 2.

Antigen-Specific Intracellular Cytokine Production upon TERT DNA Vaccination and Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Tumor-Bearing Mice

(A) Experimental setup. Mice were implanted with TC-1 tumor cells on day 0 and then immunized on days 7 and 14. Antibody delivery was started 1 day after the first immunization and continued every 3 days. Mice were sacrificed on day 21 for immune cell analysis. (B–F) Intracellular cytokine staining of CD8 or CD4 T cells after stimulation with native mouse TERT peptides for 5 hr. CD4 T cells were stained for IFN-γ (B) or TNF-α (C). CD8 T cells were stained for IFN-γ (D), TNF-α (E), or IFN-γ/CD107a/T-bet (F). Significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n = 7–10 mice per group. A representative of three independent experiments is shown. Error bars indicate ± SEM.

Surprisingly, there was no significant impact of any of the checkpoint antibodies or combinations on systemic type 1 antigen-specific CD8+ or CD4+ immune responses, including expression of interferon-gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells or IFNγ/CD107a/T-bet in CD8+ T cells compared to mTERT DNA alone (Figures 2B–2F).

Next, we examined PD-1 expression on CD4 and CD8 T cells in the spleen and the periphery of tumor-bearing mice. In tumor-bearing mice, αPD-1 had no impact on PD-1 expression in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in spleen and in the periphery (Figures 3A–3D). However, both αCTLA-4 and a combination of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 enhanced the frequency of PD-1+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in both spleen and the periphery (Figures 3A–3D).

Figure 3.

Phenotype of Peripheral and Spleen T Cells upon TERT DNA Vaccination and Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Tumor-Bearing Mice

(A–F) Staining of CD8 or CD4 T cells from spleen or peripheral blood of mice treated with the indicated therapies in accordance with the schedule in Figure 3A. CD8+ splenocytes (A) or PBMCs (B) were stained for PD-1. CD4+ splenocytes (C) or PBMCs (D) were stained for PD-1. CD4+ splenocytes (E) or PBMCs (F) were stained for CD25/FoxP3. Significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n = 7–10 mice per group. A representative of three independent experiments is shown. Error bars indicate ± SEM.

αCTLA-4 therapy is known to impact Tregs in a tissue-dependent manner, with a more profound depletion of Tregs within the tumor compared to other tissue sites.14, 36 We therefore examined the frequency of CD4+/CD25+/FoxP3+ Tregs in spleen and in the periphery upon immune checkpoint blockade therapy in combination with SynCon mTERT DNA vaccine (Figures 3E and 3F). We observed that all checkpoint therapies and combinations decreased the frequency of Tregs in spleen, but slightly increased the frequency of Tregs in the periphery (Figures 3E and 3F).

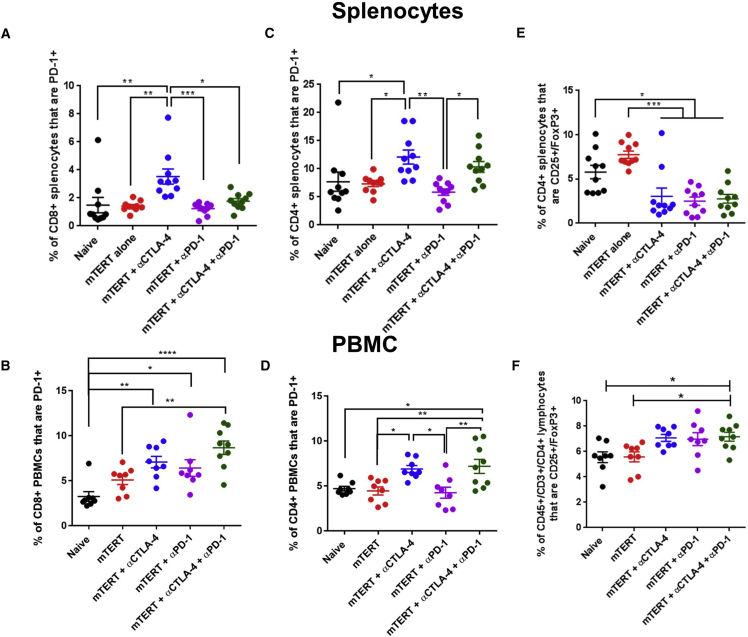

Impact of Immune Checkpoint Blockade on Tumor-Specific Immune Responses in Tumor-Bearing Mice

Because of the surprising finding that immune checkpoint blockade had no impact on TERT antigen-specific immune responses in spleen, we next examined immune responses in the tumors of these same mice. αCTLA-4 treatment resulted in significant depletion of intra-tumoral Tregs (Figure 4A), whereas αPD-1 therapy did not alter the frequency of intra-tumoral Tregs, and combination therapy with both αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 resulted in only a modest decrease in the frequency of intra-tumoral Tregs (Figure 4A). Similar to the results observed in spleen and in the peripheral T cells, the percentage of PD-1+ tumor-infiltrating CD8+ lymphocytes also increased upon αCTLA-4 treatment and, to a lesser extent, combination therapy with αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 treatment (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Phenotype of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes upon TERT DNA Vaccination and Immune Checkpoint Blockade

(A–F) Staining of CD8 or CD4 T cells isolated from the tumors of mice treated with the indicated therapies in accordance with the schedule in Figure 4A. mTERT-stimulated CD3+ TILs were stained for CD4/CD25/FoxP3 (A), CD8/PD-1 (B), CD8/CD44 (C), CD8/T-bet (E), or CD8/CD44/Tbet (F). PMA-stimulated CD3+ T cells were stained for CD8/CD44 (D). Significance was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n = 7–10 mice per group. A representative of three independent experiments is shown. Error bars indicate ± SEM.

Next, we examined the T cell activation markers CD44 and T-bet in CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). αCTLA-4 treatment alone enhanced the frequency of CD44+ CD8+ TILs (Figure 4C). This effect was more pronounced after treatment of these TILs with PMA (Figure 4D). Interestingly, αPD-1 and the combination of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 therapy did not significantly impact CD44 expression in the TILs (Figures 4C and 4D). Both αCTLA-4 and the combination of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 therapy enhanced the frequency of T-bet+ CD8+ TILs (Figure 4E). This trend was similar for CD8+ T cells that co-expressed T-bet and CD44 (Figure 4F). The SynCon TERT DNA vaccine alone did not significantly impact Tregs, PD-1, or CD44 expression in TILs (Figures 4A–4D). Together, these results demonstrate that αCTLA-4 therapy expands the effector T cell population within the tumor, likely resulting in the strong anti-tumor effect when combined with TERT DNA vaccination.

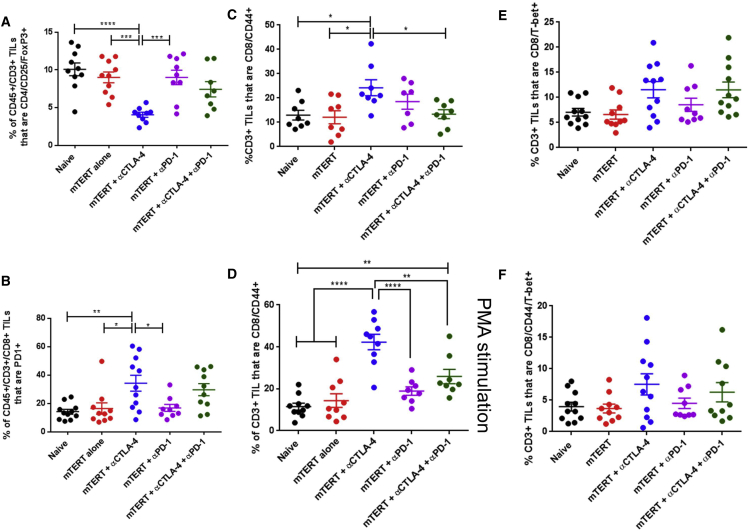

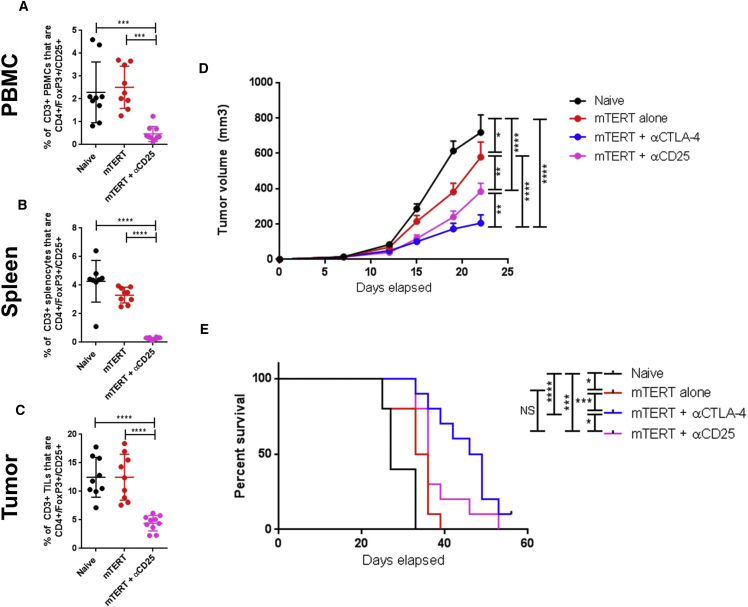

CTLA-4 Blockade Synergizes More Than Treg Depletion with mTERT DNA Vaccine

It has been proposed that the primary mechanism for αCTLA-4 therapy is depletion of Tregs in the tumor microenvironment. In order to test the contribution of Tregs to the syngery between SynCon TERT DNA vaccine and αCTLA-4 treatment, we compared the impact of αCTLA-4 to αCD25, a depletion antibody that systemically depletes Tregs.37 We verified that this αCD25 depletion antibody significantly decreased the frequency of Tregs in the peripheral blood, in spleen, and in the tumor (Figures 5A–5C). Importantly, the extent of Treg depletion in the tumor was similar to that of CTLA-4 blockade (Figures 4A and 5A). In these experiments, while αCD25 in combination with mTERT significantly improved anti-tumor responses, this effect was not as strong as combination therapy of αCTLA-4 and mTERT in terms of tumor growth or overall survival (Figures 5D and 5E). Because CD25 can also be expressed by effector T cells, we examined whether the αCD25 antibody treatment affected effector and central memory T cells (Figures S3A–S3F). We found that, in the peripheral blood, spleen and tumor, there was no depletion of effector CD8 T cells (CD44+/CD62Llo) or central memory CD8 T cells (CD44+/CD62L+) with αCD25 antibody treatment (Figures S3A–S3F). These data suggest that the mechanism of action of αCTLA-4 extends beyond depletion of Tregs in the tumor and is likely due to the expansion of effector T cells within the tumor (Figure 4).

Figure 5.

Delivery of αCTLA-4 in Combination with TERT DNA Vaccine Is Superior to Treg Depletion in Combination with TERT DNA Vaccine

(A–C) Staining of CD8 or CD4 T cells from the peripheral blood (A), spleen (B), or tumor (C) of mice treated with the indicated therapies in accordance with the schedule in Figure 2. (D) Tumor volume measurements over time for mice with indicated treatment regimen. Mice were treated in accordance with the schedule shown in Figure 2A. (E) Mouse survival over time for mice with indicated treatment regimen. Mice were euthanized if they appeared sick or if the tumor diameter exceeded 1.5 cm. Significance for tumor volume measurements was determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD test. Significance for mouse survival was determined by the Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. n = 10 mice per group. Error bars indicate ± SEM.

Discussion

Here, we utilized a synthetic consensus DNA vaccine targeting the tumor antigen TERT in combination with immune checkpoint blockade. We have previously shown strong immune responses for our SynCon DNA vaccine platform in human clinical trials for viral antigens such as HPV and Zika virus.23, 38 We have now improved this technology to help break tolerance to cancer-associated self-antigens, such as WT-1 and TERT, which we have tested in both mice and non-human primates.27, 28 Because immune checkpoint blockade is becoming the standard of care in cancer patients, it is important to understand how these novel DNA vaccine therapies can work as combination therapies.

In this study we observed robust synergy between SynCon mTERT DNA vaccination and αCTLA-4 immune checkpoint blockade. This combination exhibited long-term effects for prolonging mouse survival in a therapeutic tumor challenge model. While αPD-1 showed some synergy with SynCon mTERT DNA immunization, the effect was not as profound and did not result in significant prolongation of mouse survival. Importantly, these mice did not exhibit anti-tumor immunity after delivery of immune checkpoint antibodies alone, suggesting that addition of a DNA vaccine to an immune checkpoint blockade regimen may allow non-responders to become responders. Interesting future studies may include testing the efficacy of this combination therapy in tumor models that already show some response to immune checkpoint blockade alone, to evaluate whether increased immune potency could be achieved.

Only a handful of preclinical studies have examined the efficacy of combining DNA vaccines with immune checkpoint blockade for tumor therapy. Two studies showed modest improvement in anti-tumor immunity by combining DNA vaccines targeting the MYB oncoprotein for colorectal cancer or the SSX2 cancer antigen for sarcoma with αPD-1 antibody.39, 40 However, neither of these studies used electroporation in combination with the DNA vaccine, and therefore both vaccines exhibited minimal anti-tumor effects on their own, even when delivered only 1-2 days following tumor implantation.39, 40 In the report, the DNA vaccine targeting MYB was completely ineffective if delivered 5 days or later after tumor implantation, and was also ineffective at reducing tumor burden altogether in BALB/c mice.39 Another study combined αCTLA-4 treatment with xenogeneic DNA vaccines targeting TRP-2, gp100 or PSMA in prophylactic immunization studies.41 Interestingly, this study found that prophylactic delivery of αCTLA-4 boosted anti-tumor immunity more when given with the second immunization instead of the first immunization.41 No previous studies have examined combination therapy with DNA vaccines and αCTLA-4 blocking antibody in a therapeutic tumor challenge model. In our studies we did not observe a significant boosting in antigen-specific immune responses when αCTLA-4 was delivered following the first or second immunization. The reasons for this discrepancy are unclear, but may be antigen-dependent, or masked by the immune potency of the electroporation enhanced synthetic DNA vaccine itself.

While there are only a few studies using DNA vaccines in combination with αCTLA-4 or αPD-1 checkpoint antibodies, studies using cell-based vaccines have explored these combinations more thoroughly. Irradiated tumor cells expressing GM-CSF or Flt-3 ligand (GVAX or FVAX, respectively) have been frequently used as a vaccine for combination therapy studies with immune checkpoint blockade.5, 14, 15, 16, 17 Interestingly, the relative effects of αCTLA-4 compared to αPD-1 therapy appear to be dependent on both the type of vaccine and the tumor model. A study that utilized a PLG (poly[lactide-co-glycolide]) cancer vaccine, in which B16 tumor lysates are incorporated into PLG scaffolds, showed that αCTLA-4 therapy synergized to a greater extent than αPD-1 therapy.15 However, a study comparing GVAX and FVAX with αCTLA-4 or α-PD-1 therapy showed that for FVAX, αPD-1 therapy was superior to αCTLA-4 therapy, and for GVAX, the two therapies were similar.17 In an independent study GVAX synergized more with α-CTLA-4 therapy compared to αPD-1 therapy in CT26 tumors; however, responses to GVAX in combination with each checkpoint were similar in ID8 tumors5. In each of these cell-based vaccine studies in which triple-combination therapies were used (GVAX/FVAX, α-CTLA-4, and α-PD-1), the triple-combination therapy was profoundly superior to any of the double- or mono-therapies.5, 17 Our study showed a clear bias toward DNA vaccine synergy with α-CTLA-4 blockade over α-PD-1 blockade. Furthermore, the triple-therapy was only slightly better than double-therapy with vaccine plus αCTLA-4, indicating that patients receiving our vaccine may not benefit as much from receiving both αCTLA-4 and αPD-1. This is useful information, since the double-therapy with αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 has significantly more toxicity compared to mono-therapy with either αCTLA-4 or αPD-1 alone in humans.42

Furthermore, we did not observe a significant change in the T cell exhaustion marker PD-1 expression on CD8 or CD4 T cells in the spleen, periphery or tumor of both tumor-bearing mice after immunization with SynCon TERT DNA vaccine alone. However, in other studies upregulation of inhibitory T cell molecules, primarily PD-1, has been observed on antigen-specific CD8 T cells in both mice and humans after immunization with a variety of different vaccine platforms, including an SSX DNA vaccine, HLA-A2-restricted NY-ESO peptides formulated with Frend’s and CpG adjuvants, a recombinant lentivector vaccine expressing melanoma associated antigen epitopes, and a HPV E7 polypeptide vaccine.40, 43, 44, 45 This lack of induction of PD-1 after our potent DNA vaccine immunization may explain why less synergy was observed between our vaccine and αPD-1 therapy.

We observed an interesting increase in PD-1 expression in T cells after αCTLA-4 treatment, but not αPD-1 treatment, in tumor-bearing mice (Figure 3). Interestingly, other studies have also shown an increase in the fraction of CD8+ T cells expressing PD-1 after mono-therapy with αCTLA-4, αPD-1, or αPD-L1.17 Upregulation of PD-1+ and PD-L1+ cells was also shown in αCTLA-4 therapy for human and murine bladder cancers.33 Blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 signaling axis can only partially reverse an exhausted T cell phenotype; therefore, exploring methods of further improving immune activation in tumor-bearing mice remains important.46

Some differences between αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 blockade in the context of DNA vaccines may be the result of the different effects of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 on Tregs. αCTLA-4 antibodies, unlike αPD-1 antibodies, have demonstrated robust depletion of intra-tumoral Tregs in mice.14, 36 There is also some evidence for ipilimumab-dependent antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) ex vivo in patient samples; however, the extent to which clinical αCTLA-4 antibodies can deplete Tregs in patient tumors remains unclear.47 In the present study, αCTLA-4 antibody treatment was superior to depletion of Tregs (with an αCD25 depletion antibody) in combination with SynCon mTERT DNA vaccine (Figure 5). A separate study found a similar result when comparing combination therapy of GVAX or FVAX with αCD25 depletion, implying that αCTLA-4 has additional effects beyond simple depletion of Tregs.16 This suggests that the synergy between TERT and αCTLA-4 is most likely due to the expansion of effector CD8+ T cells within the tumor, which express the markers CD44 and T-bet, which we observed upon treatment with αCTLA-4 or αCTLA-4/αPD-1 combination therapy.

Importantly, we did not observe an increase in antigen-specific immune responses in the spleen upon combination therapy with TERT DNA vaccine and immune checkpoint blockade, despite the synergy of these therapies in inducing anti-tumor immunity. These data suggest that immune checkpoint blockade functions to alter the immune microenvironment and expand effector T cells at the tumor site rather than acting on antigen-specific cells in the periphery. It is possible that addition of immune checkpoint blockade antibodies may alter T cell trafficking and may drive antigen-specific immune cells to peripheral tissues in the mouse.

Taken together, these studies support further rational combination immune therapies with synthetic TERT DNA vaccination and immune checkpoint blockade. In addition, antigen-specific immune responses in the periphery may not correlate with efficacy in patients.

Materials and Methods

DNA Plasmids

The synthetic consensus TERT sequence was generated by using 6 TERT sequences collected from animals including mouse, rat, and hamster. The consensus sequence was obtained after alignment of these sequences using Clustal W. Two additional mutations were added to abolish telomerase activity.31, 32 All sequences were RNA and codon optimized with an immunoglobulin E (IgE) leader sequence and a Kozak sequence at the N terminus and cloned into the modified pVAX vector (Genscript). The final SynCon mouse TERT sequences shares 94.6% sequence identity with native mouse TERT.

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell and Splenocyte Isolation

For splenocyte isolation, spleens from mice were collected in complete RPMI media containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were dissociated using a stomacher and then filtered through a 40-μm mesh filter. Red blood cells were then lysed using ACK Lysis buffer (LifeTechnologies). Cells were then filtered again through a 40-μm mesh filter, counted, and plated for staining. For peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation, blood was collected in 4% sodium citrate to prevent clotting. Blood was then layered on top of Histopaque 1083 (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were spun for 1 hr, and then cells from the buffy coat were separated and stained for analysis.

Isolation of TILs

Tumors were dissociated using digestion mix, which consisted of 170 mg/L collagenase I, II, and IV (ThermoFisher), 12.5 mg/L DNase I (Roche), and 25 mg/L Elastase (Worthington) in a 50/50 mixture of Hyclone L-15 Leibowitz Media (ThermoFisher) and RPMI, supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Tumors were minced and then transferred to a 50 mL conical filled with 10 mL of digestion mix. Cells were then filtered twice through a 40-μm mesh filter, counted, and stained.

ELISpot Assay

Splenocytes were stimulated in the presence of native mouse TERT peptides (15-mer peptides spanning the entire native mouse protein, overlapping by 9 amino acids, GenScript) for 24 hr in MABTECH Mouse IFNγ ELISpotPLUS plates. Spots were developed and counted in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining and Flow Cytometry

2 million splenocytes per mouse were stimulated with native mouse TERT peptides for 5 hr in the presence of GolgiStop GolgiPlug (BD Bioscience). Phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, BD Bioscience) and complete media were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Cells were incubated with FITC α-mouse CD107a (clone 1D4B, Biolegend) during the stimulation to stain for degranulation. After stimulation, cells were washed and stained for viability using LIVE/DEAD violet. Surface stain was then added, followed by fixation and permeabilization using a FoxP3/transcription factor fixation/permeabilization kit (eBioscience). The following antibodies were used in these studies: PECy5 αCD3 (clone 145-2C11, BD PharMingen), BV510 αCD4 (clone RM4-5, Biolegend), BV605 αTNF-α (clone MP6-XT22), PE αT-bet (clone 4B10, Biolegend), BV711 αPD-1 (clone 29F.1A12, Biolegend), APC αFoxP3 (clone FJK-16 s, eBioscience), APCCy7 αCD8 (clone 53-6.7, Biolegend), AF700 αCD44 (clone IM7, Biolegend), and APC αIFNγ (clone XMG1.2, Biolegend). All data were collected on a modified LSRII flow cytometer (BD Bioscience) and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar).

Animal Immunization

Female 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Animal care was in accordance with the guidelines of the NIH and with the Wistar Institute Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Mice were immunized with 25 μg of each plasmid by intramuscular injection into the tibialis anterior (TA) muscle, followed by electroporation (EP) using the CELLECTRA-3P adaptive constant current device (Inovio Pharmaceuticals). Two 0.1-amp constant current square-wave pulses were delivered through a triangular three-electrode array. Each pulse was 52 ms in length with a 1-s delay between pulses. For immunogenicity studies, mice were given a total of three immunizations at 2-week intervals. For tumor challenge studies, mice were given a total of four immunizations at 1-week intervals.

Immune Checkpoint Blockade Antibodies

The following antibodies were used for animal studies (BioXCell): α-mouse PD-1 (clone RMP1-14), α-mouse CTLA-4 (clone 9D9), or αCD25 (clone PC-61.5.3). Mice were given 200 μg of each antibody, delivered intraperitoneally, in accordance with the schedule in each figure.

Tumor Challenge Studies

The TC-1 cell line was a gift from Dr. Yvonne Paterson from the University of Pennsylvania. This cell line was tested for Mycoplasma contamination prior to freezing the cells, and the test results were negative. Cells were thawed and cultured for fewer than 5 passages prior to implantation into mice. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cells were subcutaneously implanted onto the right flank of C57BL/6 mice (50,000 cells per mouse). 1 week following tumor implantation, mouse tumors were measured, and mice were randomized to treatment groups so that the average tumor volume and SD was equivalent between groups. Tumors were monitored twice a week with electronic calipers. Tumor volume was calculated using the following formula: volume = (π/6)*(height)*(width2). Mice were euthanized upon any sign of distress or sickness or when tumor diameters exceeded 1.5 cm, in accordance with IACUC guidelines.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software. For each experiment, error bars represent the mean ± the SEM. For all experiments, statistical significance was determined by one- or two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post hoc honest significant difference (HSD) test. For mouse survival studies, significance was determined by Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test.

Author Contributions

E.K.D, M.C.W., D.O.V., B.F., J.W., J.Y., A.K., E.M., L.H., and D.B.W. were involved in study conception and design. E.K.D., M.C.W., A.T., D.O.V., B.F., J.W., J.Y., and A.K. were involved in the acquisition, the analysis, and the interpretation of data. E.K.D. and D.B.W. drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in critically revising the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

M.C.W., B.F., J.W., J.Y., A.K., E.M., and L.H. are employees of Inovio Pharmaceuticals and as such receive salary and benefits, including ownership of stock and stock options. D.B.W. discloses grant funding, industry collaborations, speaking honoraria, and fees for consulting. His service includes serving on scientific review committees and advisory boards. Remuneration includes direct payments, stock, or stock options. He notes potential conflicts associated with his work with Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Inovio Pharmaceuticals, Touchlight, Oncosec, Merck, VGXI, and potentially others. Licensing of technology from his laboratory has created more than 150 jobs in the private sector of the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry. The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an NIH/NCI NRSA Individual Fellowship (CA213795 to E.K.D.), a Penn/Wistar Institute NIH SPORE grant (CA174523 to D.B.W.), the Wistar National Cancer Institute Cancer Center (P30 CA 010815), the W.W. Smith Family Trust (to D.B.W.), funding from the Basser Foundation (to D.B.W.), and a grant from Inovio Pharmaceuticals (to D.B.W.).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes three figures and can be found with this article online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.11.010.

Supplemental Information

References

- 1.Pardoll D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riley J.L. PD-1 signaling in primary T cells. Immunol. Rev. 2009;229:114–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walunas T.L., Bluestone J.A. CTLA-4 regulates tolerance induction and T cell differentiation in vivo. J. Immunol. 1998;160:3855–3860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson A.C. Tim-3: an emerging target in the cancer immunotherapy landscape. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:393–398. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duraiswamy J., Kaluza K.M., Freeman G.J., Coukos G. Dual blockade of PD-1 and CTLA-4 combined with tumor vaccine effectively restores T-cell rejection function in tumors. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3591–3603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodi F.S., O’Day S.J., McDermott D.F., Weber R.W., Sosman J.A., Haanen J.B., Gonzalez R., Robert C., Schadendorf D., Hassel J.C. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Postow M.A., Callahan M.K., Wolchok J.D. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015;33:1974–1982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reck M., Rodríguez-Abreu D., Robinson A.G., Hui R., Csőszi T., Fülöp A., Gottfried M., Peled N., Tafreshi A., Cuffe S., KEYNOTE-024 Investigators Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1823–1833. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robert C., Schachter J., Long G.V., Arance A., Grob J.J., Mortier L., Daud A., Carlino M.S., McNeil C., Lotem M., KEYNOTE-006 investigators Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jing W., Gershan J.A., Weber J., Tlomak D., McOlash L., Sabatos-Peyton C., Johnson B.D. Combined immune checkpoint protein blockade and low dose whole body irradiation as immunotherapy for myeloma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2015;3:2. doi: 10.1186/s40425-014-0043-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B., VanRoey M., Wang C., Chen T.H., Korman A., Jooss K. Anti-programmed death-1 synergizes with granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor--secreting tumor cell immunotherapy providing therapeutic benefit to mice with established tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:1623–1634. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang C., Wang X., Soh H., Seyedin S., Cortez M.A., Krishnan S., Massarelli E., Hong D., Naing A., Diab A. Combining radiation and immunotherapy: a new systemic therapy for solid tumors? Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:831–838. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito F., Li Q., Shreiner A.B., Okuyama R., Jure-Kunkel M.N., Teitz-Tennenbaum S., Chang A.E. Anti-CD137 monoclonal antibody administration augments the antitumor efficacy of dendritic cell-based vaccines. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8411–8419. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quezada S.A., Peggs K.S., Curran M.A., Allison J.P. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali O.A., Lewin S.A., Dranoff G., Mooney D.J. Vaccines combined with immune checkpoint antibodies promote cytotoxic T-cell activity and tumor eradication. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2016;4:95–100. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curran M.A., Allison J.P. Tumor vaccines expressing flt3 ligand synergize with ctla-4 blockade to reject preimplanted tumors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7747–7755. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curran M.A., Montalvo W., Yagita H., Allison J.P. PD-1 and CTLA-4 combination blockade expands infiltrating T cells and reduces regulatory T and myeloid cells within B16 melanoma tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4275–4280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915174107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyder A., Makarov V., Merghoub T., Yuan J., Zaretsky J.M., Desrichard A., Walsh L.A., Postow M.A., Wong P., Ho T.S. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Allen E.M., Miao D., Schilling B., Shukla S.A., Blank C., Zimmer L., Sucker A., Hillen U., Foppen M.H.G., Goldinger S.M. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350:207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bartkowiak T., Singh S., Yang G., Galvan G., Haria D., Ai M., Allison J.P., Sastry K.J., Curran M.A. Unique potential of 4-1BB agonist antibody to promote durable regression of HPV+ tumors when combined with an E6/E7 peptide vaccine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E5290–E5299. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514418112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madan R.A., Heery C.R., Gulley J.L. Combination of vaccine and immune checkpoint inhibitor is safe with encouraging clinical activity. OncoImmunology. 2012;1:1167–1168. doi: 10.4161/onci.20591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flingai S., Czerwonko M., Goodman J., Kudchodkar S.B., Muthumani K., Weiner D.B. Synthetic DNA vaccines: improved vaccine potency by electroporation and co-delivered genetic adjuvants. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:354. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trimble C.L., Morrow M.P., Kraynyak K.A., Shen X., Dallas M., Yan J. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2078–2088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00239-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagarazzi M.L., Yan J., Morrow M.P., Shen X., Parker R.L., Lee J.C., Giffear M., Pankhong P., Khan A.S., Broderick K.E. Immunotherapy against HPV16/18 generates potent TH1 and cytotoxic cellular immune responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:155ra138. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morrow M.P., Tebas P., Yan J., Ramirez L., Slager A., Kraynyak K., Diehl M., Shah D., Khan A., Lee J. Synthetic consensus HIV-1 DNA induces potent cellular immune responses and synthesis of granzyme B, perforin in HIV infected individuals. Mol. Ther. 2015;23:591–601. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kalams S.A., Parker S.D., Elizaga M., Metch B., Edupuganti S., Hural J., De Rosa S., Carter D.K., Rybczyk K., Frank I., NIAID HIV Vaccine Trials Network Safety and comparative immunogenicity of an HIV-1 DNA vaccine in combination with plasmid interleukin 12 and impact of intramuscular electroporation for delivery. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;208:818–829. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan J., Pankhong P., Shin T.H., Obeng-Adjei N., Morrow M.P., Walters J.N., Khan A.S., Sardesai N.Y., Weiner D.B. Highly optimized DNA vaccine targeting human telomerase reverse transcriptase stimulates potent antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2013;1:179–189. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walters J.N., Ferraro B., Duperret E.K., Kraynyak K.A., Chu J., Saint-Fleur A., Yan J., Levitsky H., Khan A.S., Sardesai N.Y., Weiner D.B. A novel DNA vaccine platform enhances neo-antigen-like T cell responses against WT1 to break tolerance and induce anti-tumor immunity. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:976–988. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Engelhorn M.E., Guevara-Patiño J.A., Noffz G., Hooper A.T., Lou O., Gold J.S., Kappel B.J., Houghton A.N. Autoimmunity and tumor immunity induced by immune responses to mutations in self. Nat. Med. 2006;12:198–206. doi: 10.1038/nm1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guevara-Patiño J.A., Engelhorn M.E., Turk M.J., Liu C., Duan F., Rizzuto G., Cohen A.D., Merghoub T., Wolchok J.D., Houghton A.N. Optimization of a self antigen for presentation of multiple epitopes in cancer immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1382–1390. doi: 10.1172/JCI25591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinrich S.L., Pruzan R., Ma L., Ouellette M., Tesmer V.M., Holt S.E., Bodnar A.G., Lichtsteiner S., Kim N.W., Trager J.B. Reconstitution of human telomerase with the template RNA component hTR and the catalytic protein subunit hTRT. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:498–502. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lingner J., Hughes T.R., Shevchenko A., Mann M., Lundblad V., Cech T.R. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science. 1997;276:561–567. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi L.Z., Fu T., Guan B., Chen J., Blando J.M., Allison J.P., Xiong L., Subudhi S.K., Gao J., Sharma P. Interdependent IL-7 and IFN-γ signalling in T-cell controls tumour eradication by combined α-CTLA-4+α-PD-1 therapy. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12335. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolchok J.D., Kluger H., Callahan M.K., Postow M.A., Rizvi N.A., Lesokhin A.M., Segal N.H., Ariyan C.E., Gordon R.A., Reed K. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lussier D.M., Johnson J.L., Hingorani P., Blattman J.N. Combination immunotherapy with α-CTLA-4 and α-PD-L1 antibody blockade prevents immune escape and leads to complete control of metastatic osteosarcoma. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2015;3:21. doi: 10.1186/s40425-015-0067-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Selby M.J., Engelhardt J.J., Quigley M., Henning K.A., Chen T., Srinivasan M., Korman A.J. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies of IgG2a isotype enhance antitumor activity through reduction of intratumoral regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2013;1:32–42. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens L.A., Gray D., Anderton S.M. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells limit the risk of autoimmune disease arising from T cell receptor crossreactivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:17418–17423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507454102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tebas P., Roberts C.C., Muthumani K., Reuschel E.L., Kudchodkar S.B., Zaidi F.I., White S., Khan A.S., Racine T., Choi H. Safety and immunogenicity of an anti-Zika virus DNA vaccine - preliminary report. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708120. Published online October 4, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cross R.S., Malaterre J., Davenport A.J., Carpinteri S., Anderson R.L., Darcy P.K., Ramsay R.G. Therapeutic DNA vaccination against colorectal cancer by targeting the MYB oncoprotein. Clin. Transl. Immunology. 2015;4:e30. doi: 10.1038/cti.2014.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rekoske B.T., Smith H.A., Olson B.M., Maricque B.B., McNeel D.G. PD-1 or PD-L1 blockade restores antitumor efficacy following SSX2 epitope-modified DNA vaccine immunization. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015;3:946–955. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gregor P.D., Wolchok J.D., Ferrone C.R., Buchinshky H., Guevara-Patiño J.A., Perales M.-A., Mortazavi F., Bacich D., Heston W., Latouche J.B. CTLA-4 blockade in combination with xenogeneic DNA vaccines enhances T-cell responses, tumor immunity and autoimmunity to self antigens in animal and cellular model systems. Vaccine. 2004;22:1700–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boutros C., Tarhini A., Routier E., Lambotte O., Ladurie F.L., Carbonnel F., Izzeddine H., Marabelle A., Champiat S., Berdelou A. Safety profiles of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone and in combination. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016;13:473–486. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sierro S.R., Donda A., Perret R., Guillaume P., Yagita H., Levy F., Romero P. Combination of lentivector immunization and low-dose chemotherapy or PD-1/PD-L1 blocking primes self-reactive T cells and induces anti-tumor immunity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:2217–2228. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Badoual C., Hans S., Merillon N., Van Ryswick C., Ravel P., Benhamouda N., Levionnois E., Nizard M., Si-Mohamed A., Besnier N. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:128–138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fourcade J., Sun Z., Pagliano O., Chauvin J.-M., Sander C., Janjic B., Tarhini A.A., Tawbi H.A., Kirkwood J.M., Moschos S. PD-1 and Tim-3 regulate the expansion of tumor antigen-specific CD8 þ T cells induced by melanoma vaccines. Cancer Res. 2014;74:1045–1055. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pauken K.E., Sammons M.A., Odorizzi P.M., Manne S., Godec J., Khan O., Drake A.M., Chen Z., Sen D.R., Kurachi M. Epigenetic stability of exhausted T cells limits durability of reinvigoration by PD-1 blockade. Science. 2016;354:1160–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romano E., Kusio-Kobialka M., Foukas P.G., Baumgaertner P., Meyer C., Ballabeni P., Michielin O., Weide B., Romero P., Speiser D.E. Ipilimumab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity of regulatory T cells ex vivo by nonclassical monocytes in melanoma patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:6140–6145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417320112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.