Abstract

Legionella pneumophila (L. pneumophila) is an opportunistic waterborne pathogen and the causative agent for Legionnaires' disease, which is transmitted to humans via inhalation of contaminated water droplets. The bacterium is able to colonize a variety of man-made water systems such as cooling towers, spas, and dental lines and is widely distributed in multiple niches, including several species of protozoa In addition to survival in planktonic phase, L. pneumophila is able to survive and persist within multi-species biofilms that cover surfaces within water systems. Biofilm formation by L. pneumophila is advantageous for the pathogen as it leads to persistence, spread, resistance to treatments and an increase in virulence of this bacterium. Furthermore, Legionellosis outbreaks have been associated with the presence of L. pneumophila in biofilms, even after the extensive chemical and physical treatments. In the microbial consortium-containing L. pneumophila among other organisms, several factors either positively or negatively regulate the presence and persistence of L. pneumophila in this bacterial community. Biofilm-forming L. pneumophila is of a major importance to public health and have impact on the medical and industrial sectors. Indeed, prevention and removal protocols of L. pneumophila as well as diagnosis and hospitalization of patients infected with this bacteria cost governments billions of dollars. Therefore, understanding the biological and environmental factors that contribute to persistence and physiological adaptation in biofilms can be detrimental to eradicate and prevent the transmission of L. pneumophila. In this review, we focus on various factors that contribute to persistence of L. pneumophila within the biofilm consortium, the advantages that the bacteria gain from surviving in biofilms, genes and gene regulation during biofilm formation and finally challenges related to biofilm resistance to biocides and anti-Legionella treatments.

Keywords: Legionella pneumophila, biofilm, Legionellosis, protozoa, planktonic

Introduction

Legionella pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionellosis, was recognized as being pathogenic to humans for the first time after an outbreak of acute pneumonia at a convention of the American Legion in Philadelphia, USA in July 1976 (Fraser et al., 1977). Legionella can cause two clinical syndromes in humans, Legionnaires' disease (LD), a severe form of pneumonia, and Pontiac fever, a self-limited flu-like illness. Approximately 90% of LD cases are associated with infections by L. pneumophila. The most effective bacterial dissemination mechanism is through the spread of contaminated aerosols occurring primarily in condensers, cooling towers, showers, faucets, and hot tubs (Steinert et al., 2002; Wagner et al., 2007). Despite stringent water quality examinations, the formation of contaminated aerosols remains a crucial problem for disease spread (Fields et al., 2002).

Legionella pneumophila exhibit several modes of persistence in different environmental settings and in humans. Upon invasion of amoeba or human macrophages, L. penumophila form the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV), a unique compartment with acquired components from early and late endosomes, mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), thus evading the bactericidal endocytic pathway and establishing a replicative niche (de Felipe et al., 2005; Isberg et al., 2009). The phagosome becomes a secure niche that supports the replicative phase of the bacteria. Importantly, hundreds of effector proteins synthesized by the Dot/Icm type IV secretion system of L. pneumophila. (Losick and Isberg, 2006; Abu-Zant et al., 2007; Price et al., 2011; Khweek et al., 2013; Abu Khweek et al., 2016). Like other intracellular bacteria such as Coxiella and Chlamydia, L. pneumophila alternate between a transmissive (virulent) and replicative (non-virulent) biphasic cycles to ensure bacterial survival in nutrient deprived or rich environments and transfer between different niches (Newton et al., 2010). In nutrient-rich environment, L. pneumophila enter the replicative phase and express few virulence factors. However, the switch to the transmissive phase is initiated in nutrient-limiting conditions, or when the phagosome is no longer supporting the replication phase of the bacteria. Increased motility, resistance to stressors, egress from the infected host and expression of several virulence factors are the hallmark characteristics of the transmissive phase (Newton et al., 2010). Legionella pneumophila is able to remain in the environment as free living planktonic bacteria or form bacterial biofilms that adhere to surfaces (Atlas, 1999; O'Toole et al., 2000; Mampel et al., 2006; Hindré et al., 2008; Stewart et al., 2012; Andreozzi et al., 2014). Moreover, L. pneumophila is able to differentiate into a mature intracellular form (MIF). Even though the MIF of L. pneumophila is inert and resembles cysts, it is extremely infectious (Faulkner and Garduño, 2002; Berk et al., 2008). Extracellularly, L. pneumophila enter into the viable non-culturable (VBNC) state which contributes to the resilience of this bacteria under different harsh environmental settings (Steinert et al., 1997; García et al., 2007) and hinder the detection of many Legionella species. Colonization and persistence in natural environment is mediated by biofilm formation (Valster et al., 2010), and survival within freshwater amoeba and Caenorhabditis elegans (Horwitz, 1983; Isberg et al., 2009).

Herein, we review several biological factors that contribute to biofilm persistence, the advantages that bacteria gain by being a member of the biofilm consortium and strategies to eradicate L. pneumophila biofilm.

Multispecies and monospecies L. pneumophila biofilm

In freshwater environments, L. pneumophila is found as sessile cells associated with biofilms (Declerck et al., 2009; Declerck, 2010; Stewart et al., 2012). Biofilms allow the bacteria to attach to surfaces, or to be part of other bacterial communities. This can be attained by forming an extracellular matrix (ECM) that is composed largely of water, exopolysaccharides, proteins, lipids, DNA and RNA, and inorganic compounds (Costerton et al., 1987; Costerton, 1995; Sutherland, 2001; Shirtliff et al., 2002). Bacteria that are forming biofilm cycle between three developmental different phases. Stages of biofilm formation are initiated by attachments to a substratum, followed by maturation of the biofilm and formation of the extracellular matrix, then detachments and dispersion of the bacteria. During these phases, bacterial biofilms form three-dimensional structures that are separated by water channels, which allow entry of nutrients, oxygen, and discharge of waste products. Due to the complexity of biofilms that develop in natural environments, the behavior of L. pneumophila has mainly been tested in mono- or mixed species biofilms (Mampel et al., 2006; Piao et al., 2006; Hindré et al., 2008; Pécastaings et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 2012). Interestingly, L. pneumophila represent a minor species in freshwater and environmental biofilms, (Declerck et al., 2009; Declerck, 2010), and the occurrence of L. penumophila may be affected by other microorganisms in complex biofilms (Taylor et al., 2009). Some bacterial species positively promote the persistence of L. penumophila biofilm while others exhibit inhibitory effects (Stewart et al., 2012). Intriguingly, Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), Flavobacterium sp., Empedobacter breve, Pseudomonas putida, and Pseudomonas fluorescens are among the bacterial species that positively contribute to the long-term persistence and presence of L. pneumophila in biofilms (Mampel et al., 2006; Vervaeren et al., 2006; Stewart et al., 2012). The authors reasoned that these species synthesize capsular and extracellular matrix materials which support the adherence (Kives et al., 2006; Basson et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2011), or provide the growth factors that stimulate growth of L. penumophila (Stewart et al., 2012). Other species antagonize the persistence of L. pneumophila within the biofilm such Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) (Stewart et al., 2012), Aeromonas hydrophila, Burkholderia cepacia, Acidovorax sp., and Sphingomonas sp. (Guerrieri et al., 2008). The inhibition could be due to the effect of P. aeruginosa homoserine lactone quorums sensing (QS) molecule on L. pneumophila biofilm (Mallegol et al., 2012), or production of bacteriocin (Guerrieri et al., 2008). Interestingly, L. pneumophila is able to persist in biofilm formed by P. aeruginosa and K. pneumoniae suggesting that the inhibitory effect of P. aeruginosa can be relieved by the permissive K. pneumoniae (Stewart et al., 2012). It is possible that K. pneumoniae provides the growth factors for L. pneumophila and at the same time dampens the inhibitory effect by P. aeruginosa (Stewart et al., 2012). Therefore, growth of L. pneumophila within biofilms is not only affected by the number and species of microorganisms present in the biofilm but also by the nature of interactions (commensalism or interference) between these organisms.

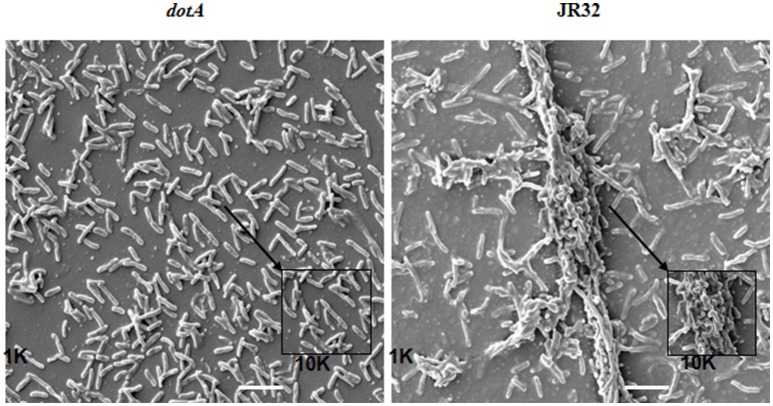

In the laboratory, L. pneumophila can form biofilm under stringent conditions in nutrient-rich Buffered Yeast Extract medium (BYE) under different temperatures (Mampel et al., 2006; Piao et al., 2006). The quantity, degree of adherence and rate of biofilm formation are correlated with different temperatures. At 25°C, L. pneumophila form mushroom-like biofilm that contain water channels. In contrast, L. pneumophila form thicker biofilm that lack the water channels at 37°C. However, the biofilm morphology of L. pneumophila grown at 42°C exhibits filamentous appearance with mat-like morphology. Furthermore, in the laboratory, we showed the ability of WT L. pneumophila to form biofilm when grown statically at 37°C for seven days as opposed to the dotA mutant that lacks the type IV secretion system (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of JR32 and dotA mutant. Larger images were captured with the 1000× objective lens while smaller images were magnified 10,000×, scale = 10 μm. The figure is adapted from Abu Khweek et al. (2013).

Even though able to persist in multispecies biofilm, little is known about the factors encoded by L. pneumophila that mediates the attachment and persistence within biofilms created by other bacteria.

Biofilms: a survival niche in oligotrophic environment

Biofilm is a rich environmental niche that harbors living and dead organisms as well as protozoa and other microflora. However, in a multispecies biofilm, the bacteria have to compete for the required nutrients to become an integrated member of the microbial community. Therefore biofilm-associated bacteria have to seek for the bacterial neighbors and the environment that best suits their growth and survival (Watnick and Kolter, 2000). Legionella pneumophila is exceptionally fastidious and require the mandatory supplementation of the laboratory media with amino acids and iron to grow (George et al., 1980; Edelstein, 1982). Therefore, survival and growth of L. pneumophila in oligotrophic environments is puzzling and indicates that the bacteria are able to utilize the essential nutrient from the bacterial community located in biofilms. Indeed, establishment of two-species and multispecies biofilms is one strategy by which L. penumophila overcome nutrients limitation in the environment. Therefore, adhering to a pre-established biofilm by other bacteria instead of attaching directly to the surface as a primary colonizer aids in L. pneumophila survival and incorporation in the biofilm community (Watnick and Kolter, 2000; Stewart et al., 2012).

Even though restricted to certain microbial species, necrotrophic feeding on the products of dead bacteria and tissues within the biofilm is likely the primary mode for deriving the required carbon, nitrogen, and amino acid for multiplication by L. pneumophila (Vervaeren et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2009). Moreover, heterotrophic bacteria support growth of L. pneumophila on media that does not usually support growth because it is deficient in L-cysteine and ferric pyrophosphate (Wadowsky and Yee, 1983). Consistent with this, L. pneumophila show satellite colonies around some aquatic bacteria including Flavobacterium breve, Pseudomonas spp., Alcaligenes spp., and Acinetobacter spp. Further, L. pneumophila are able to obtain nutrients directly from algae and to grow on the extracellular products produced by cyanobacteria under laboratory conditions (Tison et al., 1980). Further, several algae such as Scenedesmus spp., Chlorella spp., and Gleocystis spp., support the growth of L. pneumophila in basal salt media (Declerck, 2010).

The second mechanism by which L. pneumophila obtain nutrient in biofilms is through amoeba. Protozoa serve as habitats that provide the environmental host for survival and replication of Legionella species in different environmental settings (Rowbotham, 1980; Newsome et al., 1998). Various amoeba such as Acanthamoeba castellanii can use L. pneumophila as a sole food source (Tyndall and Domingue, 1982), but also amoeba contribute to spread of L. pneumophila and protect the bacteria from various adverse effects such as antibacterial agents (Loret and Greub, 2010). Notably, persistence and adaptation of L. pneumophila in various amoebal hosts has been thought to contribute to pathogenesis of the bacteria. Intriguingly, biofilm colonization with L. pneumophila can be influenced by several species of protozoa (Rowbotham, 1981; Murga et al., 2001). Indeed, L. pneumophila can parasitize more than 20 species of amoebae, three species of ciliated protozoa and one species of slime mold (Kikuhara et al., 1994; Hägele et al., 2000). Further, it has been shown that multiplication inside the amoeba increased the capacity of L. pneumophila to produce polysaccharides and therefore enhanced its capacity to establish biofilm (Bigot et al., 2013). Further, L. pneumophila is able to grow off the debris from dead amoeba (Temmerman et al., 2006), and outbreaks of L. pneumophila are directly correlated with the biomass of protozoa. Moreover, in the absence of amoeba, biofilm-associated L. pneumophila numbers did not increase. Instead, bacteria were only able to persist in the biofilm community and in some cases entered the VBNC state in order to promote their survival (Declerck, 2010). Recently, increasing evidence suggests that metazoan such as the C. elegans could represent a natural host for L. pneumophila (Brassinga et al., 2010; Hellinga et al., 2015). It has been shown that L. pneumophila survive within biofilm containing protozoan and C. elegans (Rasch et al., 2016). Together, the ability to obtain nutrient in mixed species biofilms as well as to parasitize amoeba and C. elegans enhances the survival and persistence of L. pneumophila. The diversity of organisms in the biofilm consortium provide a diverse pool of nutrients for this fastidious organism.

Factors that modulate L. pneumophila biofilm formation

Role of Cyclic-di-GMP

Cyclic-dimeric diguanylate (c-di-GMP) is a bacterial second messenger that regulates several processes including bacterial pathogenesis and biofilm formation (Tamayo et al., 2007; Abu Khweek et al., 2010; Römling et al., 2013; Martinez-Gil and Ramos, 2017). Regulation of biofilm formation by c-di-GMP has been shown for several bacteria (Bobrov et al., 2011; Valentini and Filloux, 2016; Conner et al., 2017). Synthesis of the c-di-GMP is mediated by a GGDEF domain-containing diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) from two GTPs molecules (Simm et al., 2004) and degraded by an EAL-containing phosphodiesterases (PDEs) proteins (Simm et al., 2004).

The c-di-GMP signaling play important roles in the L. pneumophila life style (Levi et al., 2011; Allombert et al., 2014; Pécastaings et al., 2016). Interestingly, the L. pneumophila genome encodes for 22–24 GGDEF/EAL proteins, which vary between strains. Furthermore, overproduction of GGDEF/EAL proteins affect the ability of L. pneumophila to replicate within amoeba and macrophages and contribute to virulence of L. pneumophila (Levi et al., 2011; Allombert et al., 2014). In L. pneumophila Lens, three GGDEF/EAL-containing proteins have been shown to positively regulate biofilm formation (Pécastaings et al., 2016). Deletion of these proteins decreased biofilm formation without significant changes in the c-di-GMP level when compared to the wild type (WT) bacteria (Pécastaings et al., 2016). However, two GGDEF/EAL-containing proteins negatively regulate biofilm formation and deletion of these proteins resulted in overproduction of biofilm but surprisingly a decrease in the level of the c-di-GMP (Pécastaings et al., 2016). Therefore, GGDEF/EAL-containing proteins regulate biofilm formation by L. pneumophila in different mechanisms when compared to other bacteria.

Regulation of biofilm formation and the c-di-GMP activity in L. pneumophila has been attributed to the Haem Nitric oxide/Oxygen (H-NOX) binding domains family of haemoprotein sensors (Carlson et al., 2010). The H-NOX proteins are widespread in bacterial genomes and L. pneumophila is the only prokaryote found to encode two H-NOX proteins. Deletion of hnox1 resulted in a hyper-biofilm formation phenotype without affecting growth in pneumophila in rich media (BYE), mouse macrophages or Acanthamoeba castellanii. Importantly, a GGDEF-containing protein is adjacent to hnox1 and has been shown to exhibit diguanylate cyclase activity in vitro and when overexpressed, L. pneumophila results in a hyper-biofilm phenotype. The diguanylate cyclase activity is inhibited by the presence of the H-NOX in the NO-bound state; suggesting the regulation of the diguanylate cyclase activity by NO (Carlson et al., 2010). Exposure to NO resulted in increase in the biofilm intensity instead of dispersing the adherent bacteria. The excessive biofilm formation seems to be associated with a decrease in the level of c-di-GMP and the c-di-GMP degrading ability could enhance biofilm formation (Pécastaings et al., 2016). In the aquatic environment, L. pneumophila can be exposed to NO when it is in close contact of denitrifying bacteria. Further, L. pneumophila is exposed to NO produced by macrophages or protozoa. Therefore, NO sensing could regulate L. pneumophila biofilm formation.

Role of iron

Iron is an essential nutrient and required for growth and replication of L. pneumophila (Reeves et al., 1981; Schaible and Kaufmann, 2004; Radtke and O'Riordan, 2006). The concentration of iron must be tightly controlled, as the excess of this metal can be toxic due to production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Andrews et al., 2003; Lemire et al., 2013). Importantly, high iron concentrations (a fivefold increase in iron pyrophosphate concentration) results in a strong inhibition of biofilm formation (Hindré et al., 2008). Furthermore, it has been shown that iron salts disturb biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa (Musk et al., 2005). Recently, the effect of iron pyrophosphate and several iron chelators on the persistence of L. pneumophila in mixed biofilm were tested (Portier et al., 2016). Addition of the iron chelator for ferrous iron, dipyridyl, DIP increased the quantity of bacteria regardless of the strain (WT or mutant in iron uptake). These data suggest a positive role for DIP in contributing to the persistence of L. pneumophila (Portier et al., 2016). Interestingly, DIP does not affect the bacterial population in biofilm or persistence of free-living amoeba in the biofilm and seems to be independent of iron acquisition systems as mutants in iron uptake were not affected by DIP. The authors hypothesized that DIP contributes to the persistence of L. pneumophila in biofilm by protecting the bacteria from the adverse effects of iron due to a decrease in ROS production (Portier et al., 2016).

Genes involved in biofilm formation by L. pneumophila

Biofilm formation plays a role in the colonization, survival, dissemination and likely the pathogenesis of L. pneumophila (Lau and Ashbolt, 2009). However, little is known about the genetic factors and the molecular events involved in this process. Among the genes that have been shown to be required for biofilm formation is the putative twin-arginine translocation pathway which is required for transport of folded proteins across the cytoplasmic membrane. Insertional inactivation of the tatB and tatC genes inhibited biofilm formation by L. pneumophila (De Buck et al., 2005). Further, a strain lacking the flagellar sigma factor FliA (σ28) was found to be impaired for biofilm accumulation in static microtiter plates (Mampel et al., 2006). FliA is required for expression of genes associated with the transmissive phase of L. pneumophila, including flagella, macrophage infection, and lysosome evasion, as well as intracellular replication within Dictyostelium discoideum (Heuner et al., 2002; Molofsky et al., 2005). In mouse macrophages infection, biofilm-derived L. pneumophila down-regulate FliA expression compared to planktonic bacteria (Abu Khweek et al., 2013). Production of flagella is controlled by stationary phase regulatory network, sensing nutrient availability as well as the L. pneumophila quorum sensing (Lqs) signaling compound LAI-1(3-hydroxypentadecane-4-one) (Schell et al., 2016). Even though flagella has been implicated in biofilm formation by other bacteria, it has been shown that the flagella is not required for attachment and persistence of L. penumophila biofilm formed by K. pneumonia (Stewart et al., 2012). This is consistent with our observation showing the down-regulation of the flagella during biofilm formation in mouse macrophage (Abu Khweek et al., 2013).

The Legionella collagen-like (LcI) is an adhesin that binds to sulfated glucosamioglycans (CAGs) of the host extracellular matrix. This gene is widely distributed among different L. pneumophila environmental and clinical isolates but absent from other Legionella species that are rarely reported in patients and poor biofilm producers; suggesting that it was acquired by L. pneumophila through horizontal gene transfer (Duncan et al., 2011). Consistent with that, the GC content of lpg2644 is different from the rest of L. pneumophila genome (Duncan et al., 2011). Further, mutation in this gene reduced biofilm formation, cell-cell adhesion and cell-matrix interactions (Duncan et al., 2011). This gene is differentially regulated during growth phases and biofilm formation (Mallegol et al., 2012). The regulation is mediated by P. aeruginosa quorum sensing (3OC12-HSL) during late stages of biofilm formation suggesting that the regulation may help in the dispersion of bacteria to reinitiate biofilm formation on another surface (Mallegol et al., 2012) which could be critical for the proliferation and dissemination of such waterborne pathogen (Lau and Ashbolt, 2009).

Quorum sensing

In Gram-negative bacteria, quorum sensing (QS) regulates gene expression of various complex bacterial processes, including virulence, sporulation, bioluminescence, competence and biofilm formation (Zhu et al., 2002; Ng and Bassler, 2009). Importantly, the bacteria that exhibit QS signaling are usually identified in man-made water systems and it is now recognized that QS systems may play a role in the regulation of environmental biofilm production (Shrout and Nerenberg, 2012). Legionella pneumophila employ LAI-1 (3-hydroxypentadecane-4-one) QS autoinducer. This is the only (Legionella quorum sensing) Lqs system that has been described to date for L. pneumophila (Tiaden et al., 2007, 2008, 2010; Spirig et al., 2008). LAI-1 is produced and detected by the Lqs system and comprises the autoinducer synthase LqsA, the homologous sensor kinases LqsS and the response regulator LqsR (Tiaden et al., 2007, 2008; Spirig et al., 2008). It is not known if the Lqs system of L. pneumophila regulates biofilm formation. However, this system is homologous to the cqsAS QS of Vibrio cholera, which is involved in cell-density dependent regulation of virulence and biofilm formation (Miller et al., 2002; Zhu et al., 2002). The P. aeruginosa quorum sensing autoinducer (3-oxo-C12-HSL) inhibits biofilm formation of L. pneumophila (Mallegol et al., 2012). This effect is associated with down-regulation of the lqsR (Kimura et al., 2009). This suggests that QS could play a role in the dispersion of L. penumophila during later stages of biofilm development.

Legionella pneumophila gene expression in biofilms

The first transcriptome analysis of L. pneumophila biofilm showed a substantial proportion of genes with differential gene expression compared to planktonic bacteria (Hindré et al., 2008). The gene expression pattern was compared with the replicative and transmissive phases during growth of L. pneumophila in A. castellanii (Brüggemann et al., 2006). Importantly, gene expression profile of sessile bacteria seems to resemble the replicative rather than the transmissive phase of L. pneumophila. This is supported by the well expression of genes involved in repression of the transmissive phase in sessile cells (Hindré et al., 2008), and suggests that biofilm is a suitable niche for L. pneumophila (Hindré et al., 2008). Among the genes that their expressions were highly induced in the sessile form are the pvcAB gene cluster which their expression is regulated by iron (Hindré et al., 2008). The pvcA and pvcB genes are homologous to the PvcA and PvcB proteins in P. aeruginosa and are required for the production of siderophore. In L. pneumophila, the pvcA and pvcB encode for a siderophore-like molecule, and might contribute to uptake and sequestration of iron below the toxic level. The second gene cluster, including ahpC2 and ahpD, encodes for alkyl hydroperoxide reductases, displayed the highest induction in biofilm cells (Rocha and Smith, 1999). These proteins play a role in protection against oxidative stress (Rocha and Smith, 1999; LeBlanc et al., 2006). It is known that iron participates in the production of reactive oxygen intermediates and that the metabolism of iron and oxidative stress is related. Induction of both pvcAB and ahpC2D genes in sessile cells could thus be related and reflect the need for protection against oxidative stress resulting from high iron concentrations.

Further, the virulence of biofilm-associated L. pneumophila was assessed by examining the expression of the macrophage infectivity potentiator (mip) to transcriptionally active L. pneumophila infected in cell culture (Andreozzi et al., 2014). Expression of mip is important for intracellular replication in protozoa and human macrophages (Cianciotto and Fields, 1992). mip expression is down-regulated during early stages of infection but up-regulated in the last stages during escape from the host cell. Therefore, mip expression is up-regulated during the transmissive stages of L. pneumophila life cycle (Wieland et al., 2005). Expression of mip was constant at early stages of biofilm formation, when the bacteria did not require a new host for growth, which is similar to the replicative phase. In contrast, mip expression was predominately up-regulated at the end of biofilm formation which is similar to the transmissive phase in vivo (Andreozzi et al., 2014). The switch to the transmissive phase observed in planktonic form could be associated with mip up-regulation. This suggests that biofilm could protect the replicative form of L. pneumophila.

Legionella pneumophila biofilm resistance, a challenge for biocides treatments

Legionella pneumophila is detected in environmental and artificial water systems as biofilms covering several environmental systems such as ventilation and conditioning systems (Lau and Ashbolt, 2009). In addition, biofilm-containing L. penumophila can become a transient or permanent habitat for other relevant microorganisms. Therefore, biofilm-associated organisms can survive for days, weeks or even months depending on the substratum and the environmental factors that stimulate biofilm formation (Blasco et al., 2008; Buse et al., 2014). To restrict L. pneumophila growth, numerous chemical, physical and thermal disinfection methods have been used against L. pneumophila (Kim et al., 2002). However, these treatments generally do not result in total elimination of the bacterium, and after a lag period, recolonization occur as quickly as the treatments are discontinued (Taylor et al., 2009). Biofilm-associated L. pneumophila is extremely resistant to disinfectants and biocides (Kim et al., 2002; Borella et al., 2005). Exposure of biofilm-encased bacteria to biocides could lead to entry into a VBNC status (Giao et al., 2009). Chlorine and its derivatives are the most common biocides used in disinfection protocols and have been shown to be appropriate in eliminating planktonic L. pneumophila but not biofilms (Cooper and Hanlon, 2010). Resistance of L. pneumophila to disinfection is due not only to its capacity to survive within biofilm, but also the bacteria exhibit the intra-amoebal life-style (Steinert et al., 1998; Hilbi et al., 2011). Therefore, amoeba- associated L. pneumophila are more resistant to disinfection possibly due to differences in membrane chemistry or life cycle stages of this primitive organism (Taylor et al., 2009; Dupuy et al., 2011). Vesicles containing intracellular L. pneumophila released by amoeba are resistant to biocide treatments (Berk et al., 1998). Notably, these vesicles remained viable for few months (Bouyer et al., 2007). Understanding the molecular mechanisms that governs the intra-amoeba related resistance should pave the way for development of new strategies to eradicate L. pneumophila.

Other methods have been used to limit L. pneumophila such as applying heat which has been shown to be effective in reducing the number of bacteria and protozoan trophozoites, but infective against killing cysts (Storey et al., 2004; Farhat et al., 2012). UV radiation is also effective when the bacteria are in direct contact with the radiation (Schwartz et al., 2003). However, higher UV intensities are required to inactivate the protozoa (Hijnen et al., 2006). Other methods have been proposed to control L. pneumophila growth such as controlling the carbon source within anthropogenic water system (Pang and Liu, 2006), or addition of phages to control bacterial or specifically L. pneumophila growth. The phage is capable of degrading polysaccharides and therefore destabilizing the biofilm (Hughes et al., 1998; Lammertyn et al., 2008). In addition, nanoparticles have been shown to be effective in reduction of L. pneumophila biofilm volume and showed some efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms (Subbiahdoss et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2012; Raftery et al., 2014). Several natural compounds (biosurfactants, antimicrobial peptides, protein and essential oil) have been shown to exhibit anti-Legionella properties (Berjeaud et al., 2016). Collectively, it is necessary to control L. pneumophila growth and their natural hosts to optimize eradication of the bacteria.

Conclusion

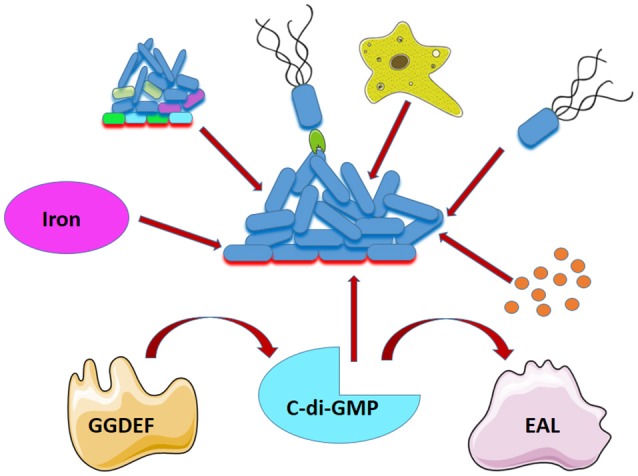

Several chemical and physical parameters can influence the behavior of L. pneumophila in biofilms, including the surface, the temperature, carbon and metal concentrations, and the presence of biocides (Wright et al., 1991; Bezanson et al., 1992; Rogers et al., 1994; Donlan et al., 2005; van der Kooij et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Mampel et al., 2006; Pang and Liu, 2006; Piao et al., 2006; Lehtola et al., 2007; Türetgen and Cotuk, 2007; Hindré et al., 2008). Biological factors such as being a member of mixed species biofilm or parasitizing free-living amoeba or nematodes influence biofilm formation by L. pneumophila (Figure 2). Biofilm- associated L. pneumophila is resistant to biocides and Legionellosis outbreaks have been attributed to biofilms. Therefore, it is essential to design new remedies for eradication of L. pneumophila biofilm in different environmental settings. Treatment studies should be performed when the bacterium is in its natural host to determine how the bacteria are protected inside the amoeba and if the passage through the natural hosts modify the resistance. Thus, preventing biofilm formation appears as one strategy to reduce water system contamination.

Figure 2.

Factors that affect L. pneumophila biofilm formation. Association of L. pneumophila in biofilm is affected by presence of other bacteria (mixed colors), adhesin (green) presence of amoeba (Yellow), flagella (black), iron (magenta), quorums sensing (orange), and the level of C-di-GMP which is affected by a GGDEF and EAL-containing proteins.

Author contributions

AAK wrote the review and AA edited the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The reviewer EC and handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ruba Khalaf from the Department of Languages and Translation at Birzeit University for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. Studies in AA laboratory are supported by The Ohio State University Center for Clinical and Translational Science Longitudinal Pilot Award (CCTS), R21 AI113477, R01 AI24121 and R01 HL127651. Studies in AAK laboratory are supported by Birzeit University.

References

- Abu Khweek A., Fernández Dávila N. S., Caution K., Akhter A., Abdulrahman B. A., Tazi M., et al. (2013). Biofilm-derived Legionella pneumophila evades the innate immune response in macrophages. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3:18. 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu Khweek A., Fetherston J. D., Perry R. D. (2010). Analysis of HmsH and its role in plague biofilm formation. Microbiology 156(Pt 5), 1424–1438. 10.1099/mic.0.036640-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu Khweek A., Kanneganti A., Guttridge D. D., Amer A. O. (2016). The sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (LegS2) contributes to the restriction of Legionella pneumophila in murine macrophages. PLoS ONE 11:e0146410. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Zant A., Jones S., Asare R., Suttles J., Price C., Graham J., Kwaik Y. A. (2007). Anti-apoptotic signalling by the Dot/Icm secretion system of L. pneumophila. Cell Microbiol. 9, 246–264. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00785.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allombert J., Lazzaroni J. C., Baïlo N., Gilbert C., Charpentier X., Doublet P., et al. (2014). Three antagonistic cyclic di-GMP-catabolizing enzymes promote differential Dot/Icm effector delivery and intracellular survival at the early steps of Legionella pneumophila infection. Infect. Immun. 82, 1222–1233. 10.1128/IAI.01077-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreozzi E., Di Cesare A., Sabatini L., Chessa E., Sisti D., Rocchi M., et al. (2014). Role of biofilm in protection of the replicative form of Legionella pneumophila. Curr. Microbiol. 69, 769–774. 10.1007/s00284-014-0648-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews S. C., Robinson A. K., Rodríguez-Quiñones F. (2003). Bacterial iron homeostasis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 215–237. 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00055-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas R. M. (1999). Legionella: from environmental habitats to disease pathology, detection and control. Environ. Microbiol. 1, 283–293. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basson A., Flemming L. A., Chenia H. Y. (2008). Evaluation of adherence, hydrophobicity, aggregation, and biofilm development of Flavobacterium johnsoniae-like isolates. Microb. Ecol. 55, 1–14. 10.1007/s00248-007-9245-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berjeaud J. M., Chevalier S., Schlusselhuber M., Portier E., Loiseau C., Aucher W., et al. (2016). Legionella pneumophila: the paradox of a highly sensitive opportunistic waterborne pathogen able to persist in the environment. Front. Microbiol. 7:486. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk S. G., Faulkner G., Garduno E., Joy M. C., Ortiz-Jimenez M. A., Garduno R. A. (2008). Packaging of live Legionella pneumophila into pellets expelled by Tetrahymena spp. does not require bacterial replication and depends on a Dot/Icm-mediated survival mechanism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2187–2199. 10.1128/AEM.01214-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk S. G., Ting R. S., Turner G. W., Ashburn R. J. (1998). Production of respirable vesicles containing live Legionella pneumophila cells by two Acanthamoeba spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 279–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanson G., Burbridge S., Haldane D., Marrie T. (1992). In situ colonization of polyvinyl chloride, brass, and copper by Legionella pneumophila. Can. J. Microbiol. 38, 328–330. 10.1139/m92-055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigot R., Bertaux J., Frere J., Berjeaud J. M. (2013). Intra-amoeba multiplication induces chemotaxis and biofilm colonization and formation for Legionella. PLoS ONE 8:e77875. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasco M. D., Esteve C., Alcaide E. (2008). Multiresistant waterborne pathogens isolated from water reservoirs and cooling systems. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105, 469–475. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrov A. G., Kirillina O., Ryjenkov D. A., Waters C. M., Price P. A., Fetherston J. D., et al. (2011). Systematic analysis of cyclic di-GMP signalling enzymes and their role in biofilm formation and virulence in Yersinia pestis. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 533–551. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07470.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borella P., Guerrieri E., Marchesi I., Bondi M., Messi P. (2005). Water ecology of Legionella and protozoan: environmental and public health perspectives. Biotechnol. Annu. Rev. 11, 355–380. 10.1016/S1387-2656(05)11011-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer S., Imbert C., Rodier M. H., Héchard Y. (2007). Long-term survival of Legionella pneumophila associated with Acanthamoeba castellanii vesicles. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 1341–1344. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01229.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassinga A. K., Kinchen J. M., Cupp M. E., Day S. R., Hoffman P. S., Sifri C. D. (2010). Caenorhabditis is a metazoan host for Legionella. Cell. Microbiol. 12, 343–361. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01398.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüggemann H., Hagman A., Jules M., Sismeiro O., Dillies M. A., Gouyette C., et al. (2006). Virulence strategies for infecting phagocytes deduced from the in vivo transcriptional program of Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1228–1240. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse H. Y., Lu J., Lu X., Mou X., Ashbolt N. J. (2014). Microbial diversities (16S and 18S rRNA gene pyrosequencing) and environmental pathogens within drinking water biofilms grown on the common premise plumbing materials unplasticized polyvinylchloride and copper. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 88, 280–295. 10.1111/1574-6941.12294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson H. K., Vance R. E., Marletta M. A. (2010). H-NOX regulation of c-di-GMP metabolism and biofilm formation in Legionella pneumophila. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 930–942. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07259.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianciotto N. P., Fields B. S. (1992). Legionella pneumophila mip gene potentiates intracellular infection of protozoa and human macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 5188–5191. 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner J. G., Zamorano-Sánchez D., Park J. H., Sondermann H., Yildiz F. H. (2017). The ins and outs of cyclic di-GMP signaling in Vibrio cholerae. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 36, 20–29. 10.1016/j.mib.2017.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper I. R., Hanlon G. W. (2010). Resistance of Legionella pneumophila serotype 1 biofilms to chlorine-based disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 74, 152–159. 10.1016/j.jhin.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J. W. (1995). Overview of microbial biofilms. J. Ind. Microbiol. 15, 137–140. 10.1007/BF01569816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costerton J. W., Cheng K. J., Geesey G. G., Ladd T. I., Nickel J. C., Dasgupta M., et al. (1987). Bacterial biofilms in nature and disease. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 41, 435–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Buck E., Maes L., Meyen E., Van Mellaert L., Geukens N., Anné J., et al. (2005). Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia-1 tatB and tatC affect intracellular replication and biofilm formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 331, 1413–1420. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declerck P. (2010). Biofilms: the environmental playground of Legionella pneumophila. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 557–566. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02025.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declerck P., Behets J., Margineanu A., van Hoef V., De Keersmaecker B., Ollevier F. (2009). Replication of Legionella pneumophila in biofilms of water distribution pipes. Microbiol. Res. 164, 593–603. 10.1016/j.micres.2007.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Felipe K. S., Pampou S., Jovanovic O. S., Pericone C. D., Ye S. F., Kalachikov S., et al. (2005). Evidence for acquisition of Legionella type IV secretion substrates via interdomain horizontal gene transfer. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7716–7726. 10.1128/JB.187.22.7716-7726.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donlan R. M., Forster T., Murga R., Brown E., Lucas C., Carpenter J., et al. (2005). Legionella pneumophila associated with the protozoan Hartmannella vermiformis in a model multi-species biofilm has reduced susceptibility to disinfectants. Biofouling 21, 1–7. 10.1080/08927010500044286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C., Prashar A., So J., Tang P., Low D. E., Terebiznik M., et al. (2011). Lcl of Legionella pneumophila is an immunogenic GAG binding adhesin that promotes interactions with lung epithelial cells and plays a crucial role in biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 79, 2168–2181. 10.1128/IAI.01304-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy M., Mazoua S., Berne F., Bodet C., Garrec N., Herbelin P., et al. (2011). Efficiency of water disinfectants against Legionella pneumophila and Acanthamoeba. Water Res. 45, 1087–1094. 10.1016/j.watres.2010.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein P. H. (1982). Comparative study of selective media for isolation of Legionella pneumophila from potable water. J. Clin. Microbiol. 16, 697–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat M., Moletta-Denat M., Frère J., Onillon S., Trouilhé M.-C., Robine E. (2012). Effects of disinfection on Legionella spp., eukarya, and biofilms in a hot water system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 6850–6858. 10.1128/AEM.00831-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner G., Garduño R. A. (2002). Ultrastructural analysis of differentiation in Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 184, 7025–7041. 10.1128/JB.184.24.7025-7041.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields B. S., Benson R. F., Besser R. E. (2002). Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15, 506–526. 10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser D. W., Tsai T. R., Orenstein W., Parkin W. E., Beecham H. J., Sharrar R. G., et al. (1977). Legionnaires' disease: description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 297, 1189–1197. 10.1056/NEJM197712012972201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García M. T., Jones S., Pelaz C., Millar R. D., Abu Kwaik Y. (2007). Acanthamoeba polyphaga resuscitates viable non-culturable Legionella pneumophila after disinfection. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 1267–1277. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George J. R., Pine L., Reeves M. W., Harrell W. K. (1980). Amino acid requirements of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 11, 286–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giao M. S., Wilks S., Azevedo N. F., Vieira M. J., Keevil C. W. (2009). Incorporation of natural uncultivable Legionella pneumophila into potable water biofilms provides a protective niche against chlorination stress. Biofouling 25, 335–341. 10.1080/08927010902802232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri E., Bondi M., Sabia C., de Niederhäusern S., Borella P., Messi P. (2008). Effect of bacterial interference on biofilm development by Legionella pneumophila. Curr. Microbiol. 57, 532–536. 10.1007/s00284-008-9237-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hägele S., Köhler R., Merkert H., Schleicher M., Hacker J., Steinert M. (2000). Dictyostelium discoideum: a new host model system for intracellular pathogens of the genus Legionella. Cell. Microbiol. 2, 165–171. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00044.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellinga J. R., Garduño R. A., Kormish J. D., Tanner J. R., Khan D., Buchko K., et al. (2015). Identification of vacuoles containing extraintestinal differentiated forms of Legionella pneumophila in colonized Caenorhabditis elegans soil nematodes. Microbiologyopen 4, 660–681. 10.1002/mbo3.271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuner K., Dietrich C., Skriwan C., Steinert M., Hacker J. (2002). Influence of the alternative sigma(28) factor on virulence and flagellum expression of Legionella pneumophila. Infect. Immun. 70, 1604–1608. 10.1128/IAI.70.3.1604-1608.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hijnen W. A., Beerendonk E. F., Medema G. J. (2006). Inactivation credit of UV radiation for viruses, bacteria and protozoan (oo)cysts in water: a review. Water Res. 40, 3–22. 10.1016/j.watres.2005.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbi H., Hoffmann C., Harrison C. F. (2011). Legionella spp. outdoors: colonization, communication and persistence. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3, 286–296. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindré T., Brüggemann H., Buchrieser C., Héchard Y. (2008). Transcriptional profiling of Legionella pneumophila biofilm cells and the influence of iron on biofilm formation. Microbiology 154(Pt 1), 30–41. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/008698-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz M. A. (1983). Formation of a novel phagosome by the Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) in human monocytes. J. Exp. Med. 158, 1319–1331. 10.1084/jem.158.4.1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K. A., Sutherland I. W., Jones M. V. (1998). Biofilm susceptibility to bacteriophage attack: the role of phage-borne polysaccharide depolymerase. Microbiology 144 (Pt 11), 3039–3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isberg R. R., O'Connor T. J., Heidtman M. (2009). The Legionella pneumophila replication vacuole: making a cosy niche inside host cells. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 13–24. 10.1038/nrmicro1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khweek A. A., Caution K., Akhter A., Abdulrahman B. A., Tazi M., Hassan H., et al. (2013). A bacterial protein promotes the recognition of the Legionella pneumophila vacuole by autophagy. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 1333–1344. 10.1002/eji.201242835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuhara H., Ogawa M., Miyamoto H., Nikaido Y., Yoshida S. (1994). Intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila in Tetrahymena thermophila. J. UOEH 16, 263–275. 10.7888/juoeh.16.263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B. R., Anderson J. E., Mueller S. A., Gaines W. A., Kendall A. M. (2002). Literature review–efficacy of various disinfectants against Legionella in water systems. Water Res. 36, 4433–4444. 10.1016/S0043-1354(02)00188-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S., Tateda K., Ishii Y., Horikawa M., Miyairi S., Gotoh N., et al. (2009). Pseudomonas aeruginosa Las quorum sensing autoinducer suppresses growth and biofilm production in Legionella species. Microbiology 155(Pt 6), 1934–1939. 10.1099/mic.0.026641-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kives J., Orgaz B., Sanjosé C. (2006). Polysaccharide differences between planktonic and biofilm-associated EPS from Pseudomonas fluorescens B52. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 52, 123–127. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammertyn E., Vande Voorde J., Meyen E., Maes L., Mast J., Anné J. (2008). Evidence for the presence of Legionella bacteriophages in environmental water samples. Microb. Ecol. 56, 191–197. 10.1007/s00248-007-9325-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H. Y., Ashbolt N. J. (2009). The role of biofilms and protozoa in Legionella pathogenesis: implications for drinking water. J. Appl. Microbiol. 107, 368–378. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04208.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc J. J., Davidson R. J., Hoffman P. S. (2006). Compensatory functions of two alkyl hydroperoxide reductases in the oxidative defense system of Legionella pneumophila. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6235–6244. 10.1128/JB.00635-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtola M. J., Torvinen E., Kusnetsov J., Pitkänen T., Maunula L., von Bonsdorff C. H., et al. (2007). Survival of Mycobacterium avium, Legionella pneumophila, Escherichia coli, and caliciviruses in drinking water-associated biofilms grown under high-shear turbulent flow. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 2854–2859. 10.1128/AEM.02916-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemire J. A., Harrison J. J., Turner R. J. (2013). Antimicrobial activity of metals: mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 371–384. 10.1038/nrmicro3028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi A., Folcher M., Jenal U., Shuman H. A. (2011). Cyclic diguanylate signaling proteins control intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila. MBio 2:e00316–10. 10.1128/mBio.00316-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Lin Y. E., Stout J. E., Hwang C. C., Vidic R. D., Yu V. L. (2006). Effect of flow regimes on the presence of Legionella within the biofilm of a model plumbing system. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101, 437–442. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.02970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loret J. F., Greub G. (2010). Free-living amoebae: biological by-passes in water treatment. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 213, 167–175. 10.1016/j.ijheh.2010.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losick V. P., Isberg R. R. (2006). NF-kappaB translocation prevents host cell death after low-dose challenge by Legionella pneumophila. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2177–2189. 10.1084/jem.20060766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallegol J., Duncan C., Prashar A., So J., Low D. E., Terebeznik M., et al. (2012). Essential roles and regulation of the Legionella pneumophila collagen-like adhesin during biofilm formation. PLoS ONE 7:e46462. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mampel J., Spirig T., Weber S. S., Haagensen J. A., Molin S., Hilbi H. (2006). Planktonic replication is essential for biofilm formation by Legionella pneumophila in a complex medium under static and dynamic flow conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2885–2895. 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2885-2895.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Gil M., Ramos C. (2017). Role of Cyclic di-GMP in the bacterial virulence and evasion of the plant immunity. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 25:199–222. 10.21775/cimb.025.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. B., Skorupski K., Lenz D. H., Taylor R. K., Bassler B. L. (2002). Parallel quorum sensing systems converge to regulate virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Cell 110, 303–314. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00829-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky A. B., Shetron-Rama L. M., Swanson M. S. (2005). Components of the Legionella pneumophila flagellar regulon contribute to multiple virulence traits, including lysosome avoidance and macrophage death. Infect. Immun. 73, 5720–5734. 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5720-5734.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga R., Forster T. S., Brown E., Pruckler J. M., Fields B. S., Donlan R. M. (2001). Role of biofilms in the survival of Legionella pneumophila in a model potable-water system. Microbiology 147(Pt 11), 3121–3126. 10.1099/00221287-147-11-3121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musk D. J., Banko D. A., Hergenrother P. J. (2005). Iron salts perturb biofilm formation and disrupt existing biofilms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chem. Biol. 12, 789–796. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsome A. L., Scott T. M., Benson R. F., Fields B. S. (1998). Isolation of an amoeba naturally harboring a distinctive Legionella species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 1688–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton H. J., Ang D. K., van Driel I. R., Hartland E. L. (2010). Molecular pathogenesis of infections caused by Legionella pneumophila. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 274–298. 10.1128/CMR.00052-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng W. L., Bassler B. L. (2009). Bacterial quorum-sensing network architectures. Annu. Rev. Genet. 43, 197–222. 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Toole G., Kaplan H. B., Kolter R. (2000). Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 49–79. 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang C. M., Liu W. T. (2006). Biological filtration limits carbon availability and affects downstream biofilm formation and community structure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5702–5712. 10.1128/AEM.02982-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pécastaings S., Allombert J., Lajoie B., Doublet P., Roques C., Vianney A. (2016). New insights into Legionella pneumophila biofilm regulation by c-di-GMP signaling. Biofouling 32, 935–948. 10.1080/08927014.2016.1212988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pécastaings S., Bergé M., Dubourg K. M., Roques C. (2010). Sessile Legionella pneumophila is able to grow on surfaces and generate structured monospecies biofilms. Biofouling 26, 809–819. 10.1080/08927014.2010.520159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao Z., Sze C. C., Barysheva O., Iida K., Yoshida S. (2006). Temperature-regulated formation of mycelial mat-like biofilms by Legionella pneumophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1613–1622. 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1613-1622.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portier E., Bertaux J., Labanowski J., Hechard Y. (2016). Iron Availability modulates the persistence of Legionella pneumophila in complex biofilms. Microb. Environ. 31, 387–394. 10.1264/jsme2.ME16010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price C. T., Al-Quadan T., Santic M., Rosenshine I., Abu Kwaik Y. (2011). Host proteasomal degradation generates amino acids essential for intracellular bacterial growth. Science 334, 1553–1557. 10.1126/science.1212868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke A. L., O'Riordan M. X. (2006). Intracellular innate resistance to bacterial pathogens. Cell. Microbiol. 8, 1720–1729. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00795.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raftery T. D., Kerscher P., Hart A. E., Saville S. L., Qi B., Kitchens C. L., et al. (2014). Discrete nanoparticles induce loss of Legionella pneumophila biofilms from surfaces. Nanotoxicology 8, 477–484. 10.3109/17435390.2013.796537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasch J., Krüger S., Fontvieille D., Ünal C. M., Michel R., Labrosse A., et al. (2016). Legionella-protozoa-nematode interactions in aquatic biofilms and influence of Mip on Caenorhabditis elegans colonization. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 306, 443–451. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2016.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves M. W., Pine L., Hutner S. H., George J. R., Harrell W. K. (1981). Metal requirements of Legionella pneumophila. J. Clin. Microbiol. 13, 688–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E. R., Smith C. J. (1999). Role of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahpCF) gene in oxidative stress defense of the obligate Anaerobe bacteroides fragilis. J. Bacteriol. 181, 5701–5710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J., Dowsett A. B., Dennis P. J., Lee J. V., Keevil C. W. (1994). Influence of plumbing materials on biofilm formation and growth of Legionella pneumophila in potable water systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 1842–1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Römling U., Galperin M. Y., Gomelsky M. (2013). Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77, 1–52. 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowbotham T. J. (1980). Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae. J. Clin. Pathol. 33, 1179–1183. 10.1136/jcp.33.12.1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowbotham T. J. (1981). Pontiac fever, amoebae, and legionellae. Lancet 1, 40–41. 10.1016/S0140-6736(81)90141-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaible U. E., Kaufmann S. H. (2004). Iron and microbial infection. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 946–953. 10.1038/nrmicro1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell U., Simon S., Hilbi H. (2016). Inflammasome recognition and regulation of the Legionella Flagellum. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 397, 161–181. 10.1007/978-3-319-41171-2_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz T., Hoffmann S., Obst U. (2003). Formation of natural biofilms during chlorine dioxide and u.v. disinfection in a public drinking water distribution system. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95, 591–601. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02019.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirtliff M. E., Mader J. T., Camper A. K. (2002). Molecular interactions in biofilms. Chem. Biol. 9, 859–871. 10.1016/S1074-5521(02)00198-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout J. D., Nerenberg R. (2012). Monitoring bacterial twitter: does quorum sensing determine the behavior of water and wastewater treatment biofilms? Environ. Sci. Technol. 46, 1995–2005. 10.1021/es203933h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simm R., Morr M., Kader A., Nimtz M., Römling U. (2004). GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol. Microbiol. 53, 1123–1134. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04206.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirig T., Tiaden A., Kiefer P., Buchrieser C., Vorholt J. A., Hilbi H. (2008). The Legionella autoinducer synthase LqsA produces an alpha-hydroxyketone signaling molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18113–18123. 10.1074/jbc.M801929200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert M., Emödy L., Amann R., Hacker J. (1997). Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Legionella pneumophila Philadelphia JR32 by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 2047–2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert M., Hentschel U., Hacker J. (2002). Legionella pneumophila: an aquatic microbe goes astray. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26, 149–162. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00607.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinert M., Ockert G., Lück C., Hacker J. (1998). Regrowth of Legionella pneumophila in a heat-disinfected plumbing system. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 288, 331–342. 10.1016/S0934-8840(98)80005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. R., Muthye V., Cianciotto N. P. (2012). Legionella pneumophila persists within biofilms formed by Klebsiella pneumoniae, Flavobacterium sp., and Pseudomonas fluorescens under dynamic flow conditions. PLoS ONE 7:e50560. 10.1371/journal.pone.0050560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey M. V., Winiecka-Krusnell J., Ashbolt N. J., Stenström T. A. (2004). The efficacy of heat and chlorine treatment against thermotolerant Acanthamoebae and Legionellae. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 36, 656–662. 10.1080/00365540410020785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbiahdoss G., Sharifi S., Grijpma D. W., Laurent S., van der Mei H. C., Mahmoudi M., et al. (2012). Magnetic targeting of surface-modified superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles yields antibacterial efficacy against biofilms of gentamicin-resistant staphylococci. Acta Biomater. 8, 2047–2055. 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland I. W. (2001). The biofilm matrix–an immobilized but dynamic microbial environment. Trends Microbiol. 9, 222–227. 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02012-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayo R., Pratt J. T., Camilli A. (2007). Roles of cyclic diguanylate in the regulation of bacterial pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:131–148. 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E. N., Kummer K. M., Durmus N. G., Leuba K., Tarquinio K. M., Webster T. J. (2012). Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPION) for the treatment of antibiotic-resistant biofilms. Small 8, 3016–3027. 10.1002/smll.201200575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Ross K., Bentham R. (2009). Legionella, protozoa, and biofilms: interactions within complex microbial systems. Microb. Ecol. 58, 538–547. 10.1007/s00248-009-9514-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temmerman R., Vervaeren H., Noseda B., Boon N., Verstraete W. (2006). Necrotrophic growth of Legionella pneumophila. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 4323–4328. 10.1128/AEM.00070-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiaden A., Spirig T., Carranza P., Brüggemann H., Riedel K., Eberl L., et al. (2008). Synergistic contribution of the Legionella pneumophila lqs genes to pathogen-host interactions. J. Bacteriol. 190, 7532–7547. 10.1128/JB.01002-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiaden A., Spirig T., Sahr T., Wälti M. A., Boucke K., Buchrieser C., et al. (2010). The autoinducer synthase LqsA and putative sensor kinase LqsS regulate phagocyte interactions, extracellular filaments and a genomic island of Legionella pneumophila. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 1243–1259. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiaden A., Spirig T., Weber S. S., Brüggemann H., Bosshard R., Buchrieser C., et al. (2007). The Legionella pneumophila response regulator LqsR promotes host cell interactions as an element of the virulence regulatory network controlled by RpoS and LetA. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 2903–2920. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tison D. L., Pope D. H., Cherry W. B., Fliermans C. B. (1980). Growth of Legionella pneumophila in association with blue-green algae (cyanobacteria). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 39, 456–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Türetgen I., Cotuk A. (2007). Monitoring of biofilm-associated Legionella pneumophila on different substrata in model cooling tower system. Environ. Monit. Assess. 125, 271–279. 10.1007/s10661-006-9519-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall R. L., Domingue E. L. (1982). Cocultivation of Legionella pneumophila and free-living amoebae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 44, 954–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentini M., Filloux A. (2016). Biofilms and Cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling: lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Other bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 12547–12555. 10.1074/jbc.R115.711507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valster R. M., Wullings B. A., van der Kooij D. (2010). Detection of protozoan hosts for Legionella pneumophila in engineered water systems by using a biofilm batch test. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 7144–7153. 10.1128/AEM.00926-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kooij D., Veenendaal H. R., Scheffer W. J. (2005). Biofilm formation and multiplication of Legionella in a model warm water system with pipes of copper, stainless steel and cross-linked polyethylene. Water Res. 39, 2789–2798. 10.1016/j.watres.2005.04.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervaeren H., Temmerman R., Devos L., Boon N., Verstraete W. (2006). Introduction of a boost of Legionella pneumophila into a stagnant-water model by heat treatment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 58, 583–592. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadowsky R. M., Yee R. B. (1983). Satellite growth of Legionella pneumophila with an environmental isolate of Flavobacterium breve. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 46, 1447–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C., Khan A. S., Kamphausen T., Schmausser B., Unal C., Lorenz U., et al. (2007). Collagen binding protein Mip enables Legionella pneumophila to transmigrate through a barrier of NCI-H292 lung epithelial cells and extracellular matrix. Cell. Microbiol. 9, 450–462. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00802.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick P., Kolter R. (2000). Biofilm, city of microbes. J. Bacteriol. 182, 2675–2679. 10.1128/JB.182.10.2675-2679.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland H., Ullrich S., Lang F., Neumeister B. (2005). Intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila depends on host cell amino acid transporter SLC1A5. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 1528–1537. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04490.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. B., Ruseska I., Costerton J. W. (1991). Decreased biocide susceptibility of adherent Legionella pneumophila. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 71, 531–538. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb03828.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M. C., Lin T. L., Hsieh P. F., Yang H. C., Wang J. T. (2011). Isolation of genes involved in biofilm formation of a Klebsiella pneumoniae strain causing pyogenic liver abscess. PLoS ONE 6:e23500. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Miller M. B., Vance R. E., Dziejman M., Bassler B. L., Mekalanos J. J. (2002). Quorum-sensing regulators control virulence gene expression in Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3129–3134. 10.1073/pnas.052694299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]