Abstract

Background

Depression and antidepressant (AD) use are highly prevalent among U.S. women, and may be related to increased breast cancer risk. However, prior studies are not in agreement regarding an increase in risk.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study within the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHSII among females age 25 and older. Over more than 10 years of follow-up in each cohort, 4,014 incident invasive breast cancers were diagnosed. We used Cox proportional hazards regressions with updating of exposures and covariates throughout follow-up to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between clinical depression and AD use with invasive breast cancer risk. Analyses were repeated separately for in situ disease, as well as stratified by estrogen receptor (ER) subtype and menopausal status at diagnosis.

Results

No statistically significant associations were observed between clinical depression (HR for reporting ≥3 times vs 0, 1.13, 95% CI 0.85–1.49) or AD use (HR for reporting ≥3 times vs 0, 0.92, 95% CI 0.80–1.05) and invasive breast cancer risk in multivariable analyses. Likewise, we observed no significant associations between clinical depression or AD use and risk of in situ, ER+, ER−, premenopausal, or postmenopausal breast cancer.

Conclusions

In the largest prospective study to date, we find no evidence that either depression or AD use increase risk of breast cancer.

Impact

The results of this study are reassuring in that neither depression nor AD use appear to be related to subsequent breast cancer risk.

Introduction

An estimated 12.3% of U.S. women aged 40–59 experience moderate or severe depressive symptoms (1). Depression increases inflammation and suppresses appropriate immune responses (2–5). These effects, and the strong relationship between depression and obesity (6,7), raise concerns that depression may increase breast cancer risk. Indeed, some (8–10) but not all (11–13), prior prospective studies reported a two- to four-fold increased breast cancer risk among women with depression.

Antidepressants (ADs) are commonly prescribed to women with depression and can effectively treat this condition. AD use within the U.S. population has quadrupled in recent decades, with 22.8% of women aged 40–59 reporting current AD use (1). ADs have anti-inflammatory effects (14,15), which might mitigate hypothesized influences of depression on breast cancer risk. However, treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the most commonly used class of AD (16), may increase circulating prolactin levels (17–19), which in turn could potentially increase breast cancer risk (20–22). Two prospective studies suggest a 50–75% increased risk of breast cancer associated with AD use or SSRI use specifically (23,24), although other studies reported no association (25–27).

There is a strong biologic rationale linking depression and AD use to breast cancer risk, yet epidemiologic studies of these relationships have important limitations. Prior work has largely included clinical samples of depressed women and/or AD users; thus observed estimates may not be generalizable to broader populations of women. Additionally, few studies have evaluated risk of breast cancer subtypes defined by invasiveness, estrogen receptor (ER) status, or menopausal status. Such factors are important for disease prognosis, and differences in risk factors for specific subtypes have been noted (28). Importantly, depression and AD use have rarely been evaluated together, despite the high concordance between these two exposures. The possibility that any increased risk associated with AD use might actually be due to the depression for which the AD is prescribed rather than the AD itself, or vice versa, has not been fully explored. A recent analysis of 313 breast cancer cases within the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) (25) was the first prospective study to jointly evaluate depression and AD use with breast cancer risk, and reported no significant association with either exposure (HR 0.96, 95% CI, 0.85–1.08; HR 1.04, 95% CI, 0.92–1.20, respectively). However, this analysis utilized a single measurement of depressive symptoms, as opposed to clinically diagnosed depression, and AD use.

Understanding whether either depression or AD use increases subsequent breast cancer risk remains an important question. We evaluated associations between these common exposures and breast cancer risk within two large prospective cohort studies, the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and NHSII, each with more than 10 years of follow-up data and biennial assessments of depression and AD use.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

The NHS (N=121,700, age 30–55 in 1976) and NHSII (N=116,429, age 25–42 in 1989) are two ongoing prospective cohort studies of registered nurses with follow-up through mailed biennial questionnaires. We included all NHS and NHSII participants who completed a study questionnaire and had no history of cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer prior to baseline for our analysis. Participants were excluded if they did not have information on clinical depression status or AD use at the beginning of the follow-up period (NHS: 2000, NHSII: 2003), resulting in 66,692 NHS women and 89,820 NHSII women available for analysis (NHS: through 2012, NHSII: through 2013).

Measurement of Depression

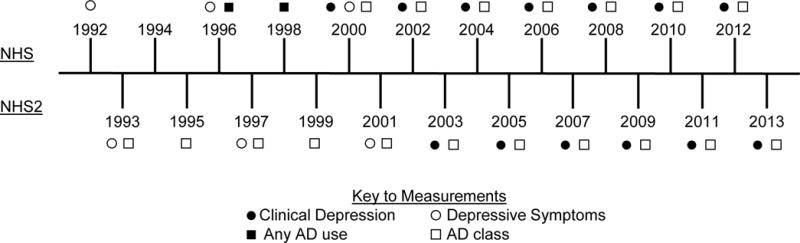

NHS and NHSII participants self-reported clinical diagnoses of depression (hereafter, “clinical depression”) on each biennial questionnaire beginning in 2000 and 2003, respectively (Figure 1). Participants reported diagnoses occurring after the date of the previous questionnaire cycle. We created a variable counting the cumulative number of times a participant reported being clinically diagnosed with depression, which we categorized as 0, 1, 2, and 3+ times. Because depression can be an episodic condition, we utilized this count variable to measure the intensity of clinical depression (i.e. women reporting clinical depression diagnoses more frequently were assumed to have chronic depression).

Figure 1.

Timeline of assessment of depression and antidepressant (AD) use in the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII). Depressive symptoms were assessed in 1992, 1996, and 2000 in NHS and in 1993, 1997, and 2001 in NHSII. Clinical depression was assessed biennially starting in 2000 in NHS and 2003 in NHSII. AD use was assessed biennially starting in 1996 in NHS, with specificity of AD class beginning in 2000. AD use by class was assessed bienially beginning in 1993 in NHSII.

Depressive symptoms were assessed via the Mental Health Inventory-5 (MHI-5) scale on the 1992, 1996, and 2000 questionnaires for NHS and the 1993, 1997, and 2001 questionnaires for NHSII, with scores ≤52 indicating severe depressive symptoms (29). As a secondary exposure definition, we counted the number of times (0, 1, 2, 3) each participant reported severe depressive symptoms. All participants provided written informed consent at the time of enrollment, and the study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This research was conducted in accordance with the Belmont Report.

Measurement of Antidepressant Use

NHS participants self-reported any current AD use (yes, no) on the 1996 and 1998 questionnaires; starting with the 2000 questionnaire NHS participants separately reported use of Prozac, Zoloft, Paxil, Celexa (SSRIs), or use of “other” ADs (with given examples of Elavil, Tofranil, and Pamelor, which are tricyclic antidepressants [TCAs]). NHSII participants self-reported use of SSRIs, TCAs, or other ADs, separately, beginning in 1993 (Figure 1). We created a variable counting the cumulative number of times a participant reported using ADs, categorized as 0, 1, 2, and 3+ times, to measure the intensity of AD use. As a secondary analysis, we also modeled the type of AD used (none, SSRI only, other AD only, SSRI and other AD) at each questionnaire.

Breast Cancer Ascertainment

Breast cancer cases were initially self-reported by NHS and NHSII with subsequent confirmation using hospital records and pathology reports and extraction of stage and hormone receptor status. Medical records were obtained for 93% and 82% of NHS and NHSII breast cancer cases, respectively, with pathology reports confirming 99% of the self-reported cases. We included only confirmed breast cancer cases through 2012 (NHS) or 2013 (NHSII).

Statistical Analysis

We examined age-adjusted differences within each cohort (NHS, NHSII) by clinical depression status and AD use status in potential confounders derived from study questionnaires at the beginning of follow-up: age (continuous), race (white, other), AD use (yes, no), depressive symptoms count (0, 1, 2, 3), history of breast cancer in first degree relative (yes, no), mammogram since previous cycle (yes, no), age at menarche (≤12, 13, ≥14), combined parity/age at first birth (nulliparous, 1–2 children/<25 yrs, 1–2 children/25–29 yrs, 1–2 children/≥30 yrs, 3–4 children/<25 yrs, 3–4 children/25–29 yrs, 3–4 children/≥30 yrs, ≥5 children/<25 yrs, ≥5 children/25–29 yrs, ≥5 children/≥30 yrs), breastfeeding history (none/<1 month, 1-<2 yrs, ≥2 yrs), menopausal status (postmenopausal, premenopausal), age at menopause (<50, 50-<55, ≥55), history of biopsy-confirmed benign breast disease (BBD) (yes, no), current oral contraceptive use (NHSII only: yes, no), type of postmenopausal hormone therapy use (premenopausal, never user, unopposed estrogen, estrogen + progesterone, progesterone only, other), BMI (<25 kg/m2, 25-<30 kg/m2, ≥30 kg/m2), early life somatotype (ordinal(30)), diabetes (yes, no), total physical activity (<3 MET/wk, 3-<9 MET/wk, 9-<18 MET/wk, 18-<27 MET/wk, ≥27 MET/wk), alcohol intake (none, <5 g/d, 5-<15 g/d, ≥15 g/d), alternative healthy eating index score (AHEI) (continuous), and smoking status (never, past, current).

We used Cox proportional hazards regressions with updating of exposure and covariates throughout follow-up to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for associations between: a) clinical depression, b) depressive symptoms, c) AD use, and d) type of AD use, and invasive breast cancer risk. Women diagnosed with in situ breast cancer also were censored at the time of their diagnosis. We first examined associations adjusted only for age and calendar year and then for age, calendar year, and BMI. To assess potential confounding by AD use on estimates of clinical depression and depressive symptoms, we fit models adjusted for AD use in addition to age and BMI; similarly, we also fit models evaluating AD use and AD type adjusted for age, BMI, and clinical depression. Finally, we fit models for each exposure adjusted for all the covariates listed above and in Tables 1 and 2. Because these adjustments minimally affected the estimates for our primary exposures, we report herein the age-adjusted and fully adjusted HRs and 95% CIs. We further examined risk of in situ disease, censoring women with diagnosis of invasive breast cancer, following a similar approach.

Table 1.

Age-standardized characteristics of study population at beginning of follow-up period, by clinical depression statusa (NHS: 2000, NHSII:2003)

| NHS | NHSII | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Depressed N=61,818 |

Clinically Depressed N=4,874 |

Not Depressed N=77,132 |

Clinically Depressed N=12,688 |

|

|

|

||||

| Age, yearsb | 66.4 (7.1) | 65.2 (7.0) | 48.3 (4.7) | 48.7 (4.6) |

| White race, % | 97.5 | 98.5 | 95.7 | 97.5 |

| Number of times reported antidepressant use, % | ||||

| 0, % | 91.9 | 22.9 | 80.7 | 16.3 |

| 1, % | 4.3 | 27.2 | 6.6 | 21.4 |

| 2, % | 2.0 | 20.9 | 6.9 | 18.8 |

| ≥3, % | 1.8 | 29.0 | 5.8 | 43.6 |

| Number of times with severe depressive symptoms, as assessed by MHI-5 | ||||

| 0, % | 93.2 | 69.9 | 86.6 | 60.5 |

| 1, % | 4.8 | 16.0 | 9.1 | 22.2 |

| 2, % | 1.4 | 8.4 | 3.1 | 11.2 |

| ≥3, % | 0.7 | 5.7 | 1.3 | 6.1 |

| History of breast cancer in first degree relative, % | 17.4 | 17.2 | 14.7 | 15.5 |

| Mammogram in previous 2 years, % | 93.3 | 94.4 | 85.3 | 85.2 |

| Age at menarche | ||||

| ≤12, % | 35.1 | 32.3 | 54.6 | 56.9 |

| 13, % | 39.6 | 41.4 | 27.6 | 25.9 |

| 14+, % | 25.3 | 26.3 | 17.8 | 17.2 |

| Nulliparous, % | 5.2 | 6.0 | 17.1 | 19.8 |

| Age at first birth, yearsc | 25.1 (3.3) | 24.9 (3.3) | 26.6 (4.7) | 26.1 (4.9) |

| Parityc | 3.2 (1.5) | 3.1 (1.4) | 2.3 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.9) |

| Breastfeeding history | ||||

| None/<1 month, % | 47.1 | 45.6 | 19.1 | 19.9 |

| 1 month - <1 year, % | 34.2 | 36.2 | 34.1 | 36.9 |

| 1-<2 years, % | 12.2 | 12.5 | 24.7 | 24.0 |

| ≥2 years, % | 6.6 | 5.7 | 22.1 | 19.2 |

| Postmenopausal, % | 98.8 | 98.9 | 42.1 | 49.0 |

| Age at menopause, yearsd | ||||

| <50 years, % | 42.3 | 44.6 | 60.9 | 66.6 |

| 50-<55 years, % | 48.5 | 47.6 | 36.9 | 31.8 |

| ≥55 years, % | 9.2 | 7.8 | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| History of benign breast disease, % | 49.9 | 61.2 | 50.2 | 58.0 |

| Current oral contraceptive use, % | – | – | 86.7 | 90.8 |

| Type of postmenopausal hormone therapy use | ||||

| Premenopausal, % | 1.4 | 1.3 | 62.4 | 56.0 |

| Never user, % | 24.2 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 13.3 |

| Unopposed estrogen, % | 34.4 | 44.3 | 11.4 | 16.6 |

| Estrogen + progesterone, % | 30.1 | 29.0 | 8.4 | 9.9 |

| Other, % | 10.0 | 12.4 | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | ||||

| <25 kg/m2, % | 42.1 | 34.7 | 46.6 | 34.2 |

| 25-<30 kg/m2, % | 34.9 | 33.2 | 28.3 | 27.6 |

| ≥30 kg/m2, % | 23.0 | 32.2 | 25.1 | 38.2 |

| Early life somatotypee | 2.7 (1.2) | 2.8 (1.2) | 2.9 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.2) |

| Diabetes, % | 8.7 | 13.0 | 3.6 | 6.8 |

| Total physical activity, MET-hrs/wk | ||||

| <3 MET-hrs/wk, % | 24.2 | 32.7 | 19.4 | 25.9 |

| 3-<9 MET-hrs/wk, % | 22.4 | 24.1 | 20.9 | 22.2 |

| 9-<18 MET-hrs/wk, % | 20.3 | 17.8 | 20.0 | 19.0 |

| 18-<27 MET-hrs/wk, % | 12.7 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 11.8 |

| ≥27 MET-hrs/wk, % | 20.4 | 15.3 | 26.4 | 21.1 |

| Alcohol intake, g/d¶ | ||||

| None, % | 41.6 | 49.7 | 35.7 | 40.9 |

| <5 g/d, % | 30.1 | 27.0 | 32.6 | 31.5 |

| 5-<15 g/d, % | 19.4 | 15.6 | 20.7 | 17.2 |

| ≥15 g/d, % | 9.0 | 7.7 | 10.9 | 10.4 |

| Alternative Healthy Eating Index scoref | 54.2 (10.5) | 53.7 (10.8) | 54.6 (13.2) | 53.4 (13.1) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never smoker, % | 45.0 | 39.3 | 66.0 | 57.0 |

| Past smoker, % | 45.9 | 49.9 | 25.7 | 30.4 |

| Current smoker, % | 9.0 | 10.9 | 8.3 | 12.6 |

Values are means (SD) or percentages and are standardized to the age distribution of the study population. Values of polytomous variables may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Clinical depression defined as self-reported of having been diagnosed with depression by a physician or other medical professional

Value is not age adjusted

Among parous women only.

Among postmenopausal women with a natural or surgical menopause.

Average of reported somatotype at ages 10 and 20.

Based on data from 1998 (NHS) or 2001 (NHSII) questionnaire.

Table 2.

Association between cumulative number of times reported clinical depression diagnosisa at each cycle and invasive breast cancer risk, NHS (2000–2012) and NHSII (2003–2013)

| All Invasive Cases | ER Positive | ER Negative | Postmenopausal at diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cases/Person-Years | Age- and calendar year Adjusted | Fully Adjustedb | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjustedb | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjustedb | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjustedb | |

| Nurses’ Health Study (N=2,667 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 2,400/734,139 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1,975/734,139 | 1 (ref) | 302/734,139 | 1 (ref) | 2,391/734,127 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 219/72,768 | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) | 0.95 (0.81–1.12) | 176/72,768 | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | 32/72,768 | 0.89 (0.58–1.38) | 219/72,768 | 0.96 (0.81–1.13) |

| 2 | 39/12,083 | 1.16 (0.84–1.59) | 1.13 (0.80–1.58) | 31/12,083 | 1.14 (0.78–1.67) | 6/12,083 | 1.14 (0.48–2.72) | 39/12,083 | 1.13 (0.80–1.58) |

| 3+ | 9/2,508 | 1.49 (0.77–2.88) | 1.44 (0.73–2.82) | 5/2,508 | 1.00 (0.41–2.44) | 3/2,508 | 2.96 (0.89–9.90) | 9/2,508 | 1.44 (0.74–2.82) |

| Nurses’ Health Study II (N=1,347 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 1,078/570,394 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 858/570,394 | 1 (ref) | 178/570,394 | 1 (ref) | 635/569,475 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 138/73,815 | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) | 1.04 (0.85–1.28) | 113/73,815 | 1.05 (0.84–1.31) | 21/73,815 | 1.06 (0.64–1.76) | 83/73,712 | 1.00 (0.77–1.29) |

| 2 | 72/38,637 | 0.94 (0.74–1.19) | 1.00 (0.76–1.31) | 56/38,637 | 0.94 (0.69–1.27) | 15/38,637 | 1.51 (0.81–2.79) | 54/38,601 | 1.08 (0.78–1.48) |

| 3+ | 59/29,276 | 1.02 (0.78–1.33) | 1.07 (0.78–1.46) | 54/29,276 | 1.11 (0.80–1.55) | 3/29,276 | 0.50 (0.15–1.69) | 46/29,252 | 1.11 (0.77–1.59) |

| Pooled (N=4,014 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 3,478/1,304,533 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 2,833/1,304,533 | 1 (ref) | 480/1,304,533 | 1 (ref) | 3026/1,303,602 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 357/146,583 | 0.97 (0.87–1.09) | 0.99 (0.87–1.12) | 289/146,583 | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | 53/146,583 | 0.96 (0.69–1.33) | 302/146,480 | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) |

| 2 | 111/50,720 | 1.01 (0.83–1.24) | 1.05 (0.85–1.29) | 87/50,720 | 1.01 (0.80–1.28) | 21/50,720 | 1.37 (0.83–2.27) | 93/50,684 | 1.10 (0.87–1.39) |

| 3+ | 68/31,784 | 1.09 (0.82–1.45) | 1.13 (0.85–1.49) | 59/31,784 | 1.10 (0.81–1.50) | 6/31,784 | 1.22 (0.21–6.99) | 55/31,760 | 1.18 (0.85–1.62) |

Clinical depression defined as self-reported of having been diagnosed with depression by a physician or other medical professional

Adjusted for age, calendar year, BMI, count of AD use, age at menarche, current oral contraceptive use (NHSII only), type of PMH use, age at menopause, age at first birth & parity, history of biopsy-confirmed benign breast disease, family history of breast cancer, mammogram in prior 2 years, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, AHEI score

We repeated analyses among invasive breast cancer cases with subtypes defined by ER status and menopausal status at diagnosis. Also, we repeated analyses incorporating inverse probability weighting based on probabilistic models of mammogram receipt (31). Separately, we repeated analyses restricting to women with a mammogram since the previous questionnaire cycle.

Analyses were conducted separately in each cohort and heterogeneity assessed by random-effects meta-analysis (32,33). Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Corporation, Cary, North Carolina).

Results

At the beginning of follow-up, 7.3% of NHS participants and 14.1% of NHSII participants self-reported clinical depression. In both cohorts, current AD use was more common among women with clinical depression than those without, as was a history of BBD, obesity, diabetes, and past and current smoking (Table 1). AD use was reported during 1, 2, or ≥3 cycles by 6.0%, 3.3%, and 3.8% of the NHS cohort in 2000 and 8.7%, 8.5%, 11.1% of the NHSII cohort in 2003, respectively. Similar patterns with descriptive characteristics were noted for AD use (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

During 12 years of follow-up in NHS, 2,667 invasive breast cancers and 658 in situ breast cancers were identified among 66,692 women; during 10 years of follow-up in NHSII, 1,347 invasive and 491 in situ breast cancers were identified among 89,820 NHSII participants.

The association between clinical depression and invasive breast cancer was similar between the two cohorts (Pheterogeneity >0.43) (Table 2). In pooled analyses, we observed no association between the number of times women self-reported clinical depression and risk of invasive breast cancer (HR for ≥3 times vs 0, 1.13, 95% CI 0.85–1.49). Likewise, clinical depression was not significantly associated with invasive disease defined by ER status or menopausal status at diagnosis. The small number of premenopausal cases (N=519) resulted in instability in HR estimates, though no association with clinical depression was apparent (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.45–1.39 for ≥3 times vs 0). We also explored the effect of depressive symptoms prior to the beginning of the follow-up period on subsequent breast cancer risk. We observed no association between depressive symptoms and invasive breast cancer overall (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.63–1.17 for ≥3 times vs 0) or defined by ER or menopausal status subtypes (Table 3). We also observed no association between clinical depression (HR 1.10, 95% CI 0.84–1.46 for ≥3 times vs 0) or depressive symptoms (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.57–1.25) and risk of in situ disease.

Table 3.

Association between cumulative number of times reported severe depressive symptomsa at each cycle and invasive breast cancer risk, NHS (2000–2012) and NHSII (2003–2013)

| All Invasive Cases | ER Positive | ER Negative | Postmenopausal at diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cases/Person-Years | Age- and calendar year Adjusted | Fully Adjustedb | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjustedb | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjustedb | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjustedb | |

| Nurses’ Health Study (N=2,667 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 2,301/760,269 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 2,028/760,269 | 1 (ref) | 313/760,269 | 1 (ref) | 2,461/751,889 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 137/45,587 | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) | 0.91 (0.77–1.09) | 109/45,587 | 0.90 (0.74–1.09) | 21/45,587 | 1.05 (0.67–1.65) | 137/45,587 | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) |

| 2 | 39/14,887 | 0.79 (0.58–1.09) | 0.79 (0.57–1.09) | 31/14,887 | 0.79 (0.55–1.13) | 7/14,887 | 1.02 (0.48–2.20) | 39/14,887 | 0.79 (0.58–1.09) |

| 3+ | 20/8,394 | 0.74 (0.48–1.15) | 0.76 (0.48–1.18) | 18/8,394 | 0.89 (0.55–1.42) | 2/8,394 | 0.51 (0.12–2.06) | 20/8,394 | 0.76 (0.49–1.19) |

| Nurses’ Health Study II (N=1,347 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 1,089/557,035 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 873/557,035 | 1 (ref) | 178/557,035 | 1 (ref) | 661/556,146 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 125/73,582 | 0.87 (0.73–1.05) | 0.88 (0.73–1.06) | 102/73,582 | 0.89 (0.72–1.09) | 18/73,582 | 0.81 (0.49–1.32) | 74/73,496 | 0.83 (0.65–1.06) |

| 2 | 58/28,254 | 1.04 (0.80–1.36) | 1.11 (0.85–1.45) | 53/28,254 | 1.24 (0.94–1.65) | 3/28,254 | 0.39 (0.12–1.22) | 37/28,210 | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) |

| 3+ | 22/12,914 | 0.86 (0.57–1.31) | 0.97 (0.63–1.48) | 15/12,914 | 0.81 (0.48–1.35) | 7/12,914 | 2.18 (1.00–4.71) | 15/12,901 | 1.01 (0.60–1.70) |

| Pooled (N=4,014 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 3,390/1,317,304 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 2,901/1,317,304 | 1 (ref) | 491/1,317,304 | 1 (ref) | 3,122/1,308,035 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 262/119,169 | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 0.90 (0.79–1.02) | 211/119,169 | 0.89 (0.77–1.03) | 39/119,169 | 0.93 (0.67–1.30) | 211/119,083 | 0.89 (0.77–1.02) |

| 2 | 97/43,141 | 0.92 (0.71–1.21) | 0.95 (0.68–1.32) | 84/43,141 | 1.01 (0.65–1.56) | 10/43,141 | 0.69 (0.27–1.77) | 76/43,097 | 0.92 (0.68–1.25) |

| 3+ | 42/21,308 | 0.80 (0.59–1.09) | 0.86 (0.63–1.17) | 33/21,308 | 0.85 (0.60–1.20) | 9/21,308 | 1.19 (0.29–4.85) | 35/21,295 | 0.86 (0.61–1.20) |

Severe depressive symptoms defined as a score ≤52 on the Mental Health Inventory-5 scale

Adjusted for age, calendar year, BMI, count of AD use, age at menarche, current oral contraceptive use (NHSII only), type of PMH use, age at menopause, age at first birth & parity, history of biopsy-confirmed benign breast disease, family history of breast cancer, mammogram in prior 2 years, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, AHEI score

Associations between AD use and invasive breast cancer also were similar across cohorts (Pheterogeneity >0.29) (Table 4). We observed no statistically significant association between the number of times AD use was reported and invasive breast cancer risk, though estimates were suggestive of an inverse association for those with the most frequent reports of AD use (≥3 times vs 0 times, HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.80–1.05). AD use was not associated with invasive disease defined by ER subtype, though the suggestion of an inverse effect was apparent only among ER+ cases and not among ER− cases. AD use was not associated with postmenopausal invasive breast cancer when separately evaluated. Again, small numbers of premenopausal cases in each AD use group led to instability in the HR estimates, though no associations with AD use were apparent (HR 1.30, 95% CI 0.65–2.60 for ≥3 times vs 0). Type of AD currently used also was not significantly associated with invasive breast cancer overall or defined by ER or menopausal status (Table 5). We observed no association between concurrent use of SSRI and other AD with invasive breast cancer (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.55–1.21), which persisted among ER-negative, postmenopausal, and premenopausal subgroups. Interestingly, we observed a statistically significant positive association between concurrent use of SSRI and other AD with in situ disease (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.00–2.94).

Table 4.

Association between cumulative number of times reported antidepressant use at each cycle and invasive breast cancer risk, NHS (2000–2012) and NHSII (2003–2013)

| All Invasive Cases | ER Positive | ER Negative | Postmenopausal at diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cases/Person-Years | Age- and calendar year Adjusted | Fully Adjusteda | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjusteda | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjusteda | Cases/Person-Years | Fully Adjusteda | |

| Nurses’ Health Study (N=2,667 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 2,194/666,501 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1,816/666,501 | 1 (ref) | 269/666,501 | 1 (ref) | 2,186/666,489 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 159/52,826 | 0.94 (0.80–1.11) | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) | 126/52,826 | 0.90 (0.75–1.09) | 23/52,826 | 1.01 (0.65–1.58) | 158/52,825 | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) |

| 2 | 100/30,851 | 1.03 (0.84–1.26) | 0.99 (0.80–1.23) | 77/30,851 | 0.93 (0.73–1.18) | 15/30,851 | 1.10 (0.63–1.92) | 100/30,851 | 1.00 (0.81–1.23) |

| 3+ | 214/71,179 | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) | 0.97 (0.82–1.15) | 168/71,179 | 0.91 (0.76–1.10) | 36/71,179 | 1.26 (0.82–1.94) | 214/71,179 | 0.98 (0.82–1.16) |

| Nurses’ Health Study II (N=1,347 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 905/478,115 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 716/478,115 | 1 (ref) | 151/478,115 | 1 (ref) | 524/477,328 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 127/61,702 | 1.09 (0.90–1.31) | 1.06 (0.87–1.29) | 103/61,702 | 1.09 (0.87–1.35) | 21/61,702 | 1.03 (0.63–1.68) | 78/61,620 | 1.06 (0.83–1.37) |

| 2 | 109/61,140 | 0.92 (0.75–1.12) | 0.88 (0.71–1.08) | 85/61,140 | 0.87 (0.68–1.10) | 21/61,140 | 0.99 (0.61–1.61) | 71/61,061 | 0.87 (0.67–1.14) |

| 3+ | 206/111,165 | 0.94 (0.80–1.09) | 0.85 (0.69–1.03) | 177/111,165 | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) | 24/111,165 | 0.62 (0.36–1.05) | 145/111,031 | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) |

| Pooled (N=4,014 cases) |

|||||||||

| 0 | 3,099/1,144,616 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 2,532/1,144,616 | 1 (ref) | 420/1,144,616 | 1 (ref) | 2,710/1,143,817 | 1 (ref) |

| 1 | 286/113,988 | 1.01 (0.87–1.16) | 0.98 (0.86–1.12) | 229/113,988 | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) | 44/113,988 | 1.02 (0.73–1.42) | 236/114,445 | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) |

| 2 | 209/91,991 | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 162/91,991 | 0.90 (0.76–1.06) | 36/91,991 | 1.03 (0.72–1.50) | 171/91,912 | 0.95 (0.80–1.12) |

| 3+ | 420/182,344 | 0.99 (0.89–1.09) | 0.92 (0.80–1.05) | 345/182,344 | 0.91 (0.79–1.05) | 60/182,344 | 0.90 (0.44–1.81) | 359/182,210 | 0.93 (0.81–1.07) |

Adjusted for age, calendar year, BMI, count of clinical depression, age at menarche, current oral contraceptive use (NHSII only), type of PMH use, age at menopause, age at first birth & parity, history of biopsy-confirmed benign breast disease, family history of breast cancer, mammogram in prior 2 years, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, AHEI score

Table 5.

Association between type of antidepressant use at each cycle and invasive breast cancer risk, NHS (2000–2012) and NHSII (2003–2013)

| All Invasive Cases | ER Positive | ER Negative | Postmenopausal at diagnosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Cases/Person- Years |

Age- and calendar year Adjusted |

Fully Adjusteda | Cases/Person- Years |

Fully Adjusteda | Cases/Person- Years |

Fully Adjusteda | Cases/Person- Years |

Fully Adjusteda | |

| Nurses’ Health Study (N=2,667 cases) |

|||||||||

| None | 2,345/726,654 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1,931/726,654 | 1 (ref) | 295/726,654 | 1 (ref) | 2,337/726,642 | 1 (ref) |

| SSRI | 194/59,047 | 1.04 (0.90–1.21) | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) | 153/59,047 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 28/59,047 | 1.04 (0.67–1.61) | 193/59,046 | 0.99 (0.84–1.17) |

| Other AD | 93/25,544 | 1.16 (0.94–1.43) | 1.13 (0.91–1.40) | 76/25,544 | 1.13 (0.89–1.44) | 14/25,544 | 1.20 (0.68–2.11) | 93/25,544 | 1.13 (0.91–1.41) |

| SSRI+Other AD | 13/4,480 | 0.95 (0.55–1.65) | 0.93 (0.53–1.62) | 8/4,480 | 0.69 (0.34–1.39) | 3/4,480 | 1.62 (0.50–5.25) | 13/4,480 | 0.93 (0.54–1.63) |

| Nurses’ Health Study II (N=1,347 cases) |

|||||||||

| None | 1,118/588,420 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 893/588,420 | 1 (ref) | 182/588,420 | 1 (ref) | 667/587,521 | 1 (ref) |

| SSRI | 145/80,001 | 0.94 (0.79–1.11) | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | 115/80,001 | 0.80 (0.64–1.01) | 26/80,001 | 0.98 (0.60–1.58) | 95/79,872 | 0.83 (0.65–1.06) |

| Other AD | 65/32,774 | 1.03 (0.80–1.32) | 0.92 (0.71–1.20) | 57/32,774 | 0.99 (0.75–1.32) | 7/32,774 | 0.63 (0.29–1.38) | 46/32,741 | 1.00 (0.73–1.37) |

| SSRI+Other AD | 13/8,425 | 0.80 (0.46–1.38) | 0.71 (0.40–1.25) | 11/8,425 | 0.72 (0.39–1.34) | 1/8,425 | 0.38 (0.05–2.76) | 8/8,409 | 0.66 (0.32–1.35) |

| Pooled (N=4,014 cases) |

|||||||||

| None | 3,463/1,315,074 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 2,824/1,315,074 | 1 (ref) | 477/1,318,074 | 1 (ref) | 3,004/1,314,163 | 1 (ref) |

| SSRI | 339/139,048 | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) | 268/139,048 | 0.89 (0.75–1.04) | 54/139,048 | 1.01 (0.73–1.39) | 288/138,918 | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) |

| Other AD | 158/58,318 | 1.10 (0.94–1.30) | 1.04 (0.85–1.26) | 133/58,318 | 1.07 (0.89–1.29) | 21/58,318 | 0.92 (0.49–1.72) | 139/58,285 | 1.09 (0.91–1.30) |

| SSRI+Other AD | 26/12,905 | 0.87 (0.59–1.29) | 0.81 (0.55–1.21) | 19/12,905 | 0.71 (0.45–1.12) | 4/12,905 | 0.98 (0.25–3.81) | 21/12,889 | 0.82 (0.53–1.27) |

Adjusted for age, calendar year, BMI, count of clinical depression, age at menarche, current oral contraceptive use (NHSII only), type of PMH use, age at menopause, age at first birth & parity, history of biopsy-confirmed benign breast disease, family history of breast cancer, mammogram in prior 2 years, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol intake, AHEI score

We observed similar results in analyses restricted to women with a mammogram since the previous cycle (e.g. HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.55–1.04 for depressive symptoms ≥3 versus 0 times).

Discussion

In these large prospective cohorts with 4,014 invasive breast cancer cases, we observed no evidence that either clinical depression or antidepressant use are associated with subsequent risk of breast cancer. The lack of association persisted among in situ cases and among subgroups of invasive disease defined by ER status and menopausal status at diagnosis.

Most prior studies reported significant positive associations between depression and breast cancer; however, such associations are not supported by our analyses. A meta-analysis of prospective studies reported a statistically non-significant 59% increased risk of breast cancer among depressed women compared to non-depressed women (10). Wide variation of results was observed, however, and many studies utilized different assessments and definitions of depression and also included only short follow-up. Two prospective studies (8,9), both within the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area sample, included >10 years of follow-up and reported a 3–4 times increased risk of breast cancer associated with clinical depression. Yet these studies did not adjust for potentially important confounders, such as AD use, BMI, or exogenous hormone use, and included far fewer breast cancer cases than our analyses (N=203 (8) and N=343 (9)). Our findings agree with those of the Women’s Health Initiative, which also reported no association between depression and breast cancer (25).

ADs were linked to increased risk of breast cancer by two recent prospective cohort studies (23,24), though no association was observed in several retrospective studies (26,27,34–37) or within the prospective WHI cohort (25). Our results are consistent with the latter studies, as we observed no associations with either frequency or type of AD use. Concerns regarding AD use have centered around the idea that SSRI use may increase circulating prolactin levels (19), which in turn promotes breast carcinogenesis (20–22). Prior reports of SSRI-related prolactin increases were based primarily on small, highly selected clinical populations. Our recent analysis within the NHS and NHSII cohorts did not observe increased prolactin levels among women using ADs or SSRIs, specifically (38), which is consistent with our present report of no relationship between AD use and breast cancer risk. The increased risk of in situ disease we observed is intriguing, yet requires confirmation in other prospective cohorts. Though not statistically significant, we noted that hazard ratio estimates tended in the direction of protective effects, especially in the case of depressive symptoms. We are unaware of biologic mechanisms that might account for depressive symptoms reducing breast cancer risk. However, women with depression are somewhat less likely to receive mammograms and other health care screenings (39), which might artificially produce a reduced breast cancer risk among women with depressive symptoms. We adjusted for mammogram receipt since previous cycle in our analyses, though the possibility of residual confounding remains. We further adjusted for mammography utilization using inverse probability weighting, whereby analyses were weighted by the inverse probability that a woman received a mammogram (31), and also by repeating among the subgroup of women who had received mammograms since the previous cycle; neither approach substantially altered the estimates, perhaps due to the high prevalence of mammography use (>93% in NHS and >85% in NHSII). Our approach to measuring depressive symptoms may also contribute to the null associations we observed. Depressive symptoms during the previous four weeks were assessed once every four years; because depression is an episodic condition, this approach may have misclassified women experiencing depressive symptoms outside of this ascertainment window as not depressed.

Our measure of clinical depression has the advantage of high specificity in classifying women with versus without depression; although self-reported, this measure captured all diagnoses occurring since the prior cycle and also includes women with the most persistent and severe depression. An ongoing validation study within NHS found a sensitivity of 56% and a specificity of 95% for self-reported clinical depression compared to diagnosis via a structured clinical interview using DSM-IV guidelines. However, lower sensitivity means that it is possible that some depressed women were classified as non-depressed in our analyses, which may have attenuated a true association. Nevertheless, previous studies within these cohorts have identified important associations with major disease outcomes, supporting the validity of this definition (7,40,41). Importantly, clinical diagnosis of depression was not associated with breast cancer risk overall or for any subtype. Additionally, some women may have reported prior clinical diagnoses of depression on later questionnaires, as opposed to new diagnoses as was instructed. This potential misclassification, along with the two year time between cycles and the lack of information on specific dates of diagnosis, prevents an accurate estimation of the duration of depression. As a result, we have referred to the “intensity” of depression as the number of times each woman reported being diagnosed with the condition. While this measure provides a reasonable proxy of duration, we could not directly assess effects of duration of depression on breast cancer risk.

Our results must be interpreted within the context of some additional limitations. AD use also was self-reported; though we have no information on validity of such reports within NHS and NHSII, all participants were registered nurses, supporting their ability to accurately report specific medication use. Further, our results were consistent with those of the WHI, where participants brought medication bottles to clinical visits. However, we lacked information on AD dose; thus, we could not address associations between AD dosage intensity and breast cancer outcomes. Also, we lacked accurate information on duration of AD use, because of the biennial nature of the questionnaires; therefore, we utilized a proxy measure of duration, referred to as “intensity” of use, which captures the number of times each participant reported AD use on a questionnaire and may roughly approximate duration of use. Additionally, bias in our results may be possible if women with depression were preferentially lost to follow-up. We believe such bias to be minimal, however, given the high retention rates in the NHS and NHSII cohort (>90%). Also, the intensity of both depression and AD use is constrained by the number of questionnaires each participant completed, therefore non-differential misclassification of exposure is possible. However, the categorizations we used (0, 1, 2, 3+) should have limited such effects, as 99% of women in each cohort returned at least three questionnaires included in our analysis. The NHS and NHSII populations are quite homogeneous with respect to race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, thus somewhat limiting the generalizability of our results. However, it is unlikely that biological pathways linking depression or AD use to breast cancer would vary substantially by race/ethnicity or socioeconomic status. Many features of the NHS and NHSII cohorts strengthen our analyses, including the large numbers of adjudicated breast cancer cases; with 4,014 incident, invasive breast cancer cases, ours is by far the largest study to date to examine associations between depression and/or AD use and breast cancer risk. Additionally, the prospective nature of the data with repeated measures of depression, AD use, and key covariates, and the extended follow-up with high retention rates are important strengths. We also examined associations separately by invasiveness, ER status, and menopausal status.

Depression is a serious medical condition, with important effects on quality of life as well as obesity and other chronic health conditions. We provide evidence that, in the absence of other risk factors, breast cancer should not be a particular concern among women with depression. Importantly, we also observed no increased risk of breast cancer due to AD use overall or by therapeutic class. These results, in particular, should provide reassurance to women and their clinicians that ADs can be used to treat depression without concern that such treatment will impact their breast cancer risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participants and staff of the Nurses’ Health Study and Nurses’ Health Study II for their valuable contributions as well as the following state cancer registries for their help: AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KY, LA, ME, MD, MA, MI, NE, NH, NJ, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, TN, TX, VA, WA, WY. The authors assume full responsibility for analyses and interpretation of these data.

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (P01CA87969), which also supports the Nurses’ Health Study (UM1CA186107, UM1CA176726). Additional support for this project was provided by the National Cancer Institute in a grant awarded to K.W. Reeves (R03CA186228).

Abbreviations

- AD

Antidepressant

- AHEI

alternative healthy eating index

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- ER

estrogen receptor

- HR

hazard ratio

- MET

metabolic equivalent

- NHS

Nurses’ Health Study

- NHSII

Nurses’ Health Study II

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- TCA

tricyclic antidepressant

- WHI

Women’s Health Initiative

References

- 1.Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression in the U S household population, 2009–2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. (NCHS Data Brief, no 172). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ader R, Cohen N, Felten D. Psychoneuroimmunology: interactions between the nervous system and the immune system. Lancet. 1995;345(8942):99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(5):446–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ma Y, Balasubramanian R, Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Hebert JR, Phillips LS, et al. Relations of Depressive Symptoms and Antidepressant Use to Body Mass Index and Selected Biomarkers for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 67(3):220–9. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pan A, Keum N, Okereke OI, Sun Q, Kivimaki M, Rubin RR, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(5):1171–80. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallo JJ, Armenian HK, Ford DE, Eaton WW, Khachaturian AS. Major depression and cancer: the 13-year follow-up of the Baltimore epidemiologic catchment area sample (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11(8):751–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1008987409499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gross AL, Gallo JJ, Eaton WW. Depression and cancer risk: 24 years of follow-up of the Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area sample. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(2):191–9. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9449-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oerlemans ME, van den Akker M, Schuurman AG, Kellen E, Buntinx F. A meta-analysis on depression and subsequent cancer risk. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:29. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aro AR, De Koning HJ, Schreck M, Henriksson M, Anttila A, Pukkala E. Psychological risk factors of incidence of breast cancer: a prospective cohort study in Finland. Psychol Med. 2005;35(10):1515–21. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn RC, Petitti DB. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-rated depression and the incidence of breast cancer. Cancer. 1988;61(4):845–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880215)61:4<845::aid-cncr2820610434>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang JA, Sun LM, Muo CH, Sung FC, Chang SN, Kao CH. The analysis of depression and subsequent cancer risk in Taiwan. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(3):473–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenis G, Maes M. Effects of antidepressants on the production of cytokines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(4):401–12. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702003164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pizzi C, Mancini S, Angeloni L, Fontana F, Manzoli L, Costa GM. Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy on endothelial function and inflammatory markers in patients with coronary heart disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;86(5):527–32. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):848–56. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balsa JA, Sanchez-Franco F, Pazos F, Lara JI, Lorenzo MJ, Maldonado G, et al. Direct action of serotonin on prolactin, growth hormone, corticotropin and luteinizing hormone release in cocultures of anterior and posterior pituitary lobes: autocrine and/or paracrine action of vasoactive intestinal peptide. Neuroendocrinology. 1998;68(5):326–33. doi: 10.1159/000054381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Emiliano AB, Fudge JL. From galactorrhea to osteopenia: rethinking serotonin-prolactin interactions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(5):833–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madhusoodanan S, Parida S, Jimenez C. Hyperprolactinemia associated with psychotropics–a review. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(4):281–97. doi: 10.1002/hup.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Rosner B, Sluss P, Hankinson SE. Plasma prolactin concentrations and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64(18):6814–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Sluss P, Hankinson SE. A prospective study of plasma prolactin concentrations and risk of premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1482–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.6356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tworoger SS, Eliassen AH, Zhang X, Qian J, Sluss PM, Rosner BA, et al. A 20-year prospective study of plasma prolactin as a risk marker of breast cancer development. Cancer Res. 2013;73(15):4810–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haukka J, Sankila R, Klaukka T, Lonnqvist J, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, et al. Incidence of cancer and antidepressant medication: record linkage study. Int J Cancer. 2010;126(1):285–96. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato I, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Toniolo PG, Akhmedkhanov A, Koenig K, Shore RE. Psychotropic medication use and risk of hormone-related cancers: the New York University Women’s Health Study. J Public Health Med. 2000;22(2):155–60. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown SB, Hankinson SE, Arcaro KF, Qian J, Reeves KW. Depression, Antidepressant Use, and Postmenopausal Breast Cancer Risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(1):158–64. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashbury JE, Levesque LE, Beck PA, Aronson KJ. A population-based case-control study of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and breast cancer: the impact of duration of use, cumulative dose and latency. BMC Med. 2010;8:90. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ashbury JE, Levesque LE, Beck PA, Aronson KJ. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Antidepressants, Prolactin and Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2012;2:177. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE, Jr, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care. 1991;29(2):169–76. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baer HJ, Tworoger SS, Hankinson SE, Willett WC. Body fatness at young ages and risk of breast cancer throughout life. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(11):1183–94. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook NR, Rosner BA, Hankinson SE, Colditz GA. Mammographic screening and risk factors for breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1422–32. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang M, Spiegelman D, Kuchiba A, Lochhead P, Kim S, Chan AT, et al. Statistical methods for studying disease subtype heterogeneity. Stat Med. 2016;35(5):782–800. doi: 10.1002/sim.6793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Ritz J, Albanes D, Beeson WL, Bernstein L, et al. Methods for pooling results of epidemiologic studies: the Pooling Project of Prospective Studies of Diet and Cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(11):1053–64. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coogan PF, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Rosenberg L. Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and the risk of breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(9):835–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coogan PF, Strom BL, Rosenberg L. SSRI use and breast cancer risk by hormone receptor status. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;109(3):527–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9664-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fulton-Kehoe D, Rossing MA, Rutter C, Mandelson MT, Weiss NS. Use of antidepressant medications in relation to the incidence of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(7):1071–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker AJ, Card T, Bates TE, Muir K. Tricyclic antidepressants and the incidence of certain cancers: a study using the GPRD. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(1):193–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reeves KW, Okereke OI, Qian J, Tworoger SS, Rice MS, Hankinson SE. Antidepressant use and circulating prolactin levels. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(7):853–61. doi: 10.1007/s10552-016-0758-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell AJ, Pereira IE, Yadegarfar M, Pepereke S, Mugadza V, Stubbs B. Breast cancer screening in women with mental illness: comparative meta-analysis of mammography uptake. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205(6):428–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.147629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan A, Okereke OI, Sun Q, Logroscino G, Manson JE, Willett WC, et al. Depression and incident stroke in women. Stroke. 2011;42(10):2770–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.617043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan A, Sun Q, Okereke OI, Rexrode KM, Rubin RR, Lucas M, et al. Use of antidepressant medication and risk of type 2 diabetes: results from three cohorts of US adults. Diabetologia. 2012;55(1):63–72. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2268-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.