Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate institutional volume-outcome relationships in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) with subanalyses of ECMO in patients with a primary diagnosis of respiratory failure.

Methods

All institutions with adult ECMO discharges in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from 2002 to 2011 were evaluated. International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision) codes were used to identify ECMO-treated patients, indications, and concurrent procedures. Patients who were treated with ECMO after cardiotomy were excluded. Annual institutional and national volume of ECMO hospitalizations varied widely, hence the number of ECMO cases performed at an institution was calculated for each year independently. Institutions were grouped into high-, medium-, and low-volume terciles by year. Statistical analysis included hierarchical, multivariable logistic regression.

Results

The in-hospital mortality rates for ECMO admissions at low-, medium-, and high-volume ECMO centers were 48% (n =467), 60% (n =285), and 57% (n = 445), respectively (p = 0.001). In post hoc pairwise comparisons, patients in low-volume hospitals were more likely to survive to discharge compared with patients in medium-volume (p = 0.001) and high-volume (p = 0.005) hospitals. There was no significant difference in survival between medium-volume and high-volume hospitals (p = 0.81). In a subanalysis of patients with respiratory failure, low-volume ECMO centers maintained the lowest rates of in-hospital mortality (47%), versus 61% in medium-volume institutions (p = 0.045) and 56% in high-volume institutions (p = 0.15). Multivariable logistical regression produced similar results in the entire study sample and in patients with respiratory failure.

Conclusions

ECMO outcomes in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample do not follow a traditional volume-outcome relationship, and these results suggest that, in properly selected patients, ECMO can be performed with acceptable results in U.S. centers that do not perform a high volume of ECMO.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) support has been used as a salvage therapy for patients with cardiac and or respiratory failure since its first report in 1972 [1]. ECMO was not initially widely adopted in adults because of early experiences and clinical trials that failed to show significant clinical benefit despite higher resource use [2]. More recent improvements in ECMO technology and patient management have led to a notable increase in ECMO use in adults, with as much as a sixfold national increase in ECMO use from 2007 to 2012 [3–5]. Despite increased use and wider adoption of ECMO at a greater number of centers, national outcomes have remained relatively stable over this same period of time [6, 7]. It is unknown whether the high but stable mortality rate is consistently experienced across most institutions or whether these results reflect certain subgroups of patients or institutions with heterogeneous outcomes.

Institutional ECMO volume and clinical outcome associations in adult patients could possibly explain trends in national ECMO outcomes and have yet to be fully examined. The association between improved outcomes and higher clinical volume has been demonstrated in various aspects of medicine and surgery [8–12]. An analysis of ECMO in pediatric patients demonstrated a volume-outcome relationship with decreased mortality at institutions performing at least 30 ECMO cases per year [13, 14]. For adult ECMO, professional recommendations have proposed a minimal institutional experience of 20 annual ECMO cases, with 12 cases specifically in respiratory patients for centers to perform ECMO for respiratory failure [15]. Additionally, an analysis of an international ECMO registry showed improved outcomes at high-volume institutions performing greater than 30 cases annually compared with low-volume institutions with fewer than six annual ECMO cases [16].

The purpose of this study was to evaluate volume-outcome relationships in U.S. ECMO centers within the context of the recent growth in ECMO use across the United States, as captured by the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). Additionally, the study evaluates the distribution of ECMO centers that could qualify for the a priori volume cutoff established by other studies and professional recommendations with a subanalysis of outcomes of ECMO in patients with respiratory failure.

Material and Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. A total of approximately 80 million records from the NIS for 2002 to 2011 were obtained from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer database and includes patients from Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance, as well as the uninsured. Records are collected in a rigorous fashion to reflect a 20% sample of all U.S. hospital admissions, with the exception of admissions to rehabilitation hospitals and federal hospitals such as Veterans Affairs hospitals. Each year all discharges are taken from a selected group of hospitals to make up the representative sample. Approximately 7 to 8 million records are included each year; the NIS sample from 2011 included data from more than 1,049 hospitals in 46 states [17].

All institutions with discharges of adult patients who underwent ECMO in the NIS from 2002 to 2011 were evaluated. The International Classification of Diseases, ninth Revision (ICD-9) was used to identify discharge records with the ECMO procedural codes of 39.65 (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) and 39.66 (percutaneous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation). Other inclusion criteria included age 18 years old or older. ECMO-treated patients were classified by clinical indication using a modified version of a previously standardized method [18]. The six mutually exclusive clinical indications were postcardiotomy status, cardiogenic shock or cardiopulmonary failure, respiratory failure and severe lung disease, pre– and post–heart transplantation status, pre– and post–lung transplantation status, and trauma or drowning/miscellaneous. Patients who received ECMO after cardiotomy were excluded, with the exception of heart or lung transplantation recipients.

Annual institutional and national volume of ECMO hospitalizations varied from year to year, so volume assignments were determined on a year-to-year basis using the unique hospital identification number to calculate the total number of ECMO hospitalizations at a particular institution in a given year. After annual volume assignments were completed, univariate regression was used to identify hospital volume cutoffs that represented the 33rd and 67th percentiles of institutional ECMO volume in each year independently. Because of the predominance of low-volume institutions in the institutional distribution and the significant separation in annual volume between the highest-volume centers and the medium-volume centers, the number of patients identified in medium-volume hospitals was lower than those identified in low-volume and high-volume institutions, respectively. This finding is consistent with previous volume-outcome distributions in NIS data [19]. A modified Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was applied to ICD-9 diagnosis codes to generate common comorbidities [20].

The primary outcome of the study was discharge survival, with ECMO-treated patients stratified by institutional volume. Subanalyses were also performed to analyze the most contemporary ECMO experience defined as 2008 to 2011 and to evaluate outcomes in patients undergoing ECMO for respiratory failure. Means, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for continuous variables. Analysis of variance was used for multigroup comparisons along with post hoc pairwise comparisons. Categorical variables were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 test. Hierarchical, multivariable logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations using an exchangeable correlation structure were used to assess risk factors and to adjust for potential similarities among patients within institutions. Mann-Kendall tests were used for trends over time. p Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analysis was performed on SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

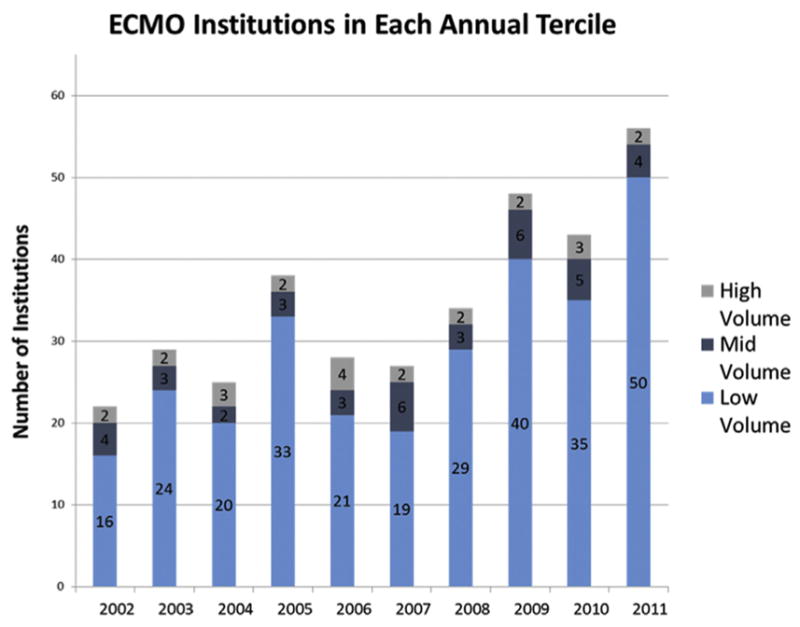

From 2002 to 2011, there were 1,197 admissions and 246 hospitals in the entire sample. The number of institutions performing ECMO in the NIS increased from 22 in 2002 to 34 in 2008 and 56 in 2011 (Fig 1) (p < 0.01). Because national and institutional ECMO volumes varied in the NIS from year to year, Figure 2 shows the volume tercile cutoffs from 2002 to 2011. The overall age for the study cohort was 48 ± 17 years, and in-hospital mortality rate for the entire study period was 54%. Patient-related demographics and comorbidities for the entire cohort and volume terciles are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age or sex among volume terciles. Few patient-related demographics and comorbidities showed a trend that paralleled institutional ECMO volume, meaning higher-risk patients at one end or the other of the institutional volume spectrum. However, some significant differences in patients’ comorbidities occurred; the medium-volume tercile demonstrated a higher prevalence of congestive heart failure, pulmonary circulation disorder, and hypertension. There were also differences in the primary indication for ECMO. Low-volume centers had a higher percentage of patients with cardiogenic shock and respiratory failure, and medium-and high-volume centers had a higher relative percentage of transplant recipients (Table 2).

Fig 1.

Institutions performing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in each annual tercile from 2002 to 2012. The number of hospitals in each volume tercile varied based on the 33% and 67% cutoff for that year. Overall, there was a significant increase in the number of institutions performing ECMO from 2002 to 2012.

Fig 2.

Institutional volume terciles by year. The 33% and 67% cutoffs for tercile volumes varied from year depending on the total and institution annual extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) volumes.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics of Patients Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the National Inpatient Sample from 2002 to 2011 Stratified by Annual Institutional Volume

| Variable | Low Volume n= 467 |

Medium Volume n = 285 |

High Volume n = 445 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 55% (259) | 56% (159) | 59% (261) | 0.5831 |

| Age (years) | 47 ± 18 | 48 ± 17 | 48 ± 17 | 0.6005 |

| White | 64% (224) | 67% (176) | 75% (244) | 0.0086 |

| Elective admission | 25% (115) | 31% (89) | 16% (69) | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 16% (74) | 27% (77) | 19% (84) | 0.0008 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorder | 12% (54) | 15% (44) | 13% (58) | 0.3095 |

| Hypertension (complicated) | 24% (112) | 25% (72) | 14% (64) | 0.0002 |

| Diabetes (complicated) | 3% (13) | 2% (6) | 0% (2) | 0.0239 |

| Coagulopathy | 27% (127) | 36% (102) | 33% (149) | 0.0268 |

| Anemia | 7% (33) | 7% (21) | 7% (31) | 0.9782 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 7% (35) | 5% (15) | 5% (24) | 0.3199 |

| Chronic lung disease | 13% (59) | 9% (27) | 9% (40) | 0.1608 |

| Liver disease | 2% (10) | 2% (7) | 3% (12) | 0.8611 |

| Renal failure | 6% (28) | 9% (27) | 6% (27) | 0.1329 |

| Obesity | 6% (30) | 7% (21) | 4% (19) | 0.1745 |

| Weight loss (frailty) | 10% (48) | 9% (27) | 18% (81) | 0.0002 |

Table 2.

Case Mix and Primary Indication for Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Stratified by Institutional Volume

| Primary Indication | Low Volume (n = 467) | Medium Volume (n = 285) | High Volume (n = 445) | p Value (Pearson’s χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart transplant | 4% | 8% | 6% | 0.019 |

| Lung transplant | 5% | 11% | 18% | <0.01 |

| Cardiogenic shock or cardiopulmonary failure | 59% | 55% | 47% | <0.01 |

| Respiratory failure | 31% | 25% | 29% | 0.027 |

| Trauma or drowning | 1% | 1% | 1% | 0.358 |

Unadjusted in-hospital mortality rates for ECMO admissions for the entire cohort and for patients with respiratory failure are shown in Table 3. Low-, medium-, and high-volume ECMO centers had mortality rates of 48%, 60%, and 57%, respectively (p = 0.001). In post hoc pairwise comparisons, patients at low-volume hospitals were more likely to survive to discharge compared with patients in medium-volume (p = 0.001) and high-volume (p = 0.005) hospitals. There was no significant difference in survival between medium-volume and high-volume hospitals (p = 0.81). The results for the logistic regression model adjusting for patient characteristics, case mix, and clustering within institutions are shown in Table 4. After adjusting for baseline patient-related demographics, patients’ comorbidities, ECMO indications, and potential similarities among patients within a single institution, low-volume centers continued to demonstrate significantly lower mortality rate compared with high-volume centers (odds ratio [OR]: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.36 to 0.75; p < 0.01). There was no significant difference between medium-volume and high-volume centers (OR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.65 to 1.39; p = 0.81).

Table 3.

Mortality and Other Outcomes for Patients Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

| Outcome | Low Volume (n = 467) | Medium Volume (n = 285) | High Volume (n = 445) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital death | 48% (224) | 60% (172) | 57% (255) | 0.0012 |

| Length of stay (days) | 16 ± 22 | 25 ± 28 | 27 ± 32 | <0.0001 |

| Days from ECMO insertion to death or discharge | 11 ± 18 | 21 ± 27 | 20 ± 26 | <0.0001 |

ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 4.

Hierarchical, Multivariable Logistic Regression for In-Hospital Mortality of Patients Undergoing Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Limits | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-volume institution | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.76 | <0.01 |

| Medium-volume institution | 0.96 | 0.65 | 1.39 | 0.81 |

| White | 0.79 | 0.60 | 1.03 | 0.08 |

| Male | 1.85 | 1.49 | 2.30 | <0.01 |

| Elective admission | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.70 | <0.01 |

| Heart transplanta | 0.93 | 0.47 | 1.82 | 0.83 |

| Lung transplanta | 0.37 | 0.23 | 0.60 | <0.01 |

| Respiratory failurea | 0.68 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.04 |

| Trauma or drowninga | 1.28 | 0.27 | 6.01 | 0.75 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.44 | 1.00 | 2.07 | 0.048 |

| Hypertension (complicated) | 0.41 | 0.28 | 0.61 | <0.01 |

| Diabetes (complicated) | 0.86 | 0.28 | 2.65 | 0.79 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorder | 2.05 | 1.34 | 3.14 | <0.01 |

| Chronic lung disease | 0.63 | 0.42 | 0.96 | 0.03 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.58 | 1.11 | 2.26 | 0.01 |

| Anemia | 0.69 | 0.45 | 1.07 | 0.1 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.05 | 0.59 | 1.88 | 0.87 |

| Obesity | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.77 | <0.01 |

| Renal failure | 0.82 | 0.49 | 1.36 | 0.44 |

| Weight loss (frailty) | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.34 | <0.01 |

Compared with cardiogenic shock or cardiopulmonary failure.

Institutional volume was also evaluated as a continuous variable, which did not show higher in-hospital mortality (OR: 1.01; 95% CI: 0.99 to 1.02; p = 0.07). When institutions were stratified by less than six, six to 29, and 30 or more cases per year, low-volume centers were associated with lower mortality compared with high-volume centers (OR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.24 to 75; p < 0.01), and no significant difference was seen between centers performing 6 to 29 cases and those with 30 or more cases (OR: 0.99; 95% CI: 0.56 to 1.76; p = 0.99). Considering the dramatic rise in national ECMO volume starting in 2008, a subanalysis of ECMO cases from 2008 to 2011 was performed and showed no significant difference in outcomes between low and high terciles (OR: 1.; 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.64; p = 0.28) and significantly worse outcomes in medium-volume terciles compared with high-volume terciles (OR: 2.4; 95% CI: 1.6 to 3.6; p < 0.01).

Outcomes were also analyzed by primary indication for ECMO, which are included in Table 4. Compared with patients with cardiogenic shock, lung transplant recipients and patients with respiratory failure demonstrated significantly better survival. A subanalysis of patients with respiratory failure showed that low-volume ECMO centers maintained the lowest unadjusted rates of in-hospital mortality (47%), in contrast to 61% in medium-volume institutions (p = 0.045) and 56% in high-volume institutions (p = 0.15). A multivariable model of the subpopulation of patients with respiratory failure failed to show a significant difference in adjusted mortality rates among volume terciles for both low-volume (OR: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.65 to 2.1; p = 0.59) and medium-volume (OR: 2.1; 95% CI: 0.95 to 4.5; p = 0.06) institutions compared with high-volume centers.

Comment

The most important finding of this study is that the association between incremental increases in clinical volume and better outcomes is not detectable in the U. S. adult ECMO experience, as captured by the NIS. Contrary to traditional volume-outcome associations, low-volume ECMO centers consistently demonstrated no difference or better in-hospital mortality rates than did medium-volume or high-volume ECMO institutions. Because of the unconventional nature of this finding, the association between institutional volume and in-hospital mortality was evaluated in several different ways, including unadjusted comparisons and hierarchical, multivariable models both in the entire study population, in subpopulations of respiratory failure, and in the more contemporary ECMO experience. Results consistently demonstrated that higher-volume centers did not have significantly better survival rates, but instead, low-volume institutions had the lowest mortality rates, whereas medium- and high-volume centers tended to have similar results. The one important exception to this pattern was that high-volume centers demonstrated lower in-hospital mortality rates compared with medium-volume centers in the more recent ECMO experience from 2008 to 2011.

Some studies have demonstrated that accurate volume-outcome analyses should be performed using hierarchical, multivariable models and not reported solely as unadjusted comparisons or single-level logistic regression analyses [21, 22]. A recent study by Barbaro and colleagues [16] using these methods evaluated ECMO volume-outcomes relationships as captured by the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization international registry. Their analysis demonstrated that the initial significant volume-outcome associations found in neonatal and pediatric ECMO with unadjusted and single-level logistical analyses were no longer statistically significant in the hierarchical, multivariable regression analysis [16]. The analysis in our study used a similar methodology of hierarchical logistic regression to adjust for differences in patient populations both among different institutions and in patients clustered within institutions.

The results of this study demonstrate an unexpected ECMO mortality rate in low-volume centers that is lower or no different compared with medium- and high-volume centers. Comparisons between medium-volume and high-volume centers tended to show higher mortality rates associated with medium-volume hospitals, but this difference was generally not statistically significant. Lower or equivalent mortality rates in low-volume ECMO centers were consistently demonstrated throughout the analyses of different time periods and different subpopulations, including patients with respiratory failure. These results contrast with traditional volume-outcome relationships in medicine, surgery, and other cardiovascular interventions [8–12]. Another study that evaluated volume-outcome relationships in adult ECMO demonstrated a significant volume-outcome relationship using Extracorporeal Life Support Organization data, when volume was evaluated as a continuous variable, in categories, and in a more recent ECMO era (2008 to 2013) [16]. Our study differs from the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization study in that outcomes do not depend on registry participation but instead are part of mandatory hospital reporting, and only U.S. institutions are included in this study. When subgroup analysis was performed in this study for more recent patients (2008 to 2011), there was no difference between low-volume and high-volume hospitals, but there was a significantly higher mortality rate in medium-volume compared with high-volume hospitals. An additional factor that could have influenced both the increase in ECMO use and the outcomes during this period was the development of new ECMO technology, including the dual-lumen cannulas used for venovenous ECMO and the evolution of management of patients undergoing ECMO to include ambulatory EMCO [23].

Associations between institutional ECMO volume and clinical outcomes have unique implications because ECMO is a resource-intensive, time-sensitive, high-risk intervention performed on patients in extremis. ECMO volume-outcome analyses can have potential implications on the diffusion of ECMO technology. National use of ECMO has undergone a rapid expansion beginning predominantly in 2008, with this study demonstrating a 250% increase in institutions performing ECMO as captured by the NIS. Considering the complexity and acuity of managing patients on ECMO, theoretical support exists for establishing ECMO referral centers to achieve optimal results. There does appear to be some evidence for the emergence of ECMO specialty centers in other studies, as judged by an increased percentage of patients transferred for ECMO support over a similar time period as this study [24]. There is also an argument for a more horizontal disbursement of ECMO technology regardless of volume cutoffs that would provide patients increased access to this technology in a more timely fashion and potentially result in better outcomes. Finally, other investigators have advocated for a combination of these strategies into a “spoke and wheel” model in which patients requiring long-term ECMO support are transferred to referral centers with transplant and bridging capabilities. Patients who recover quickly or who are deemed nonretrievable would remain at the facility of initial presentation [25].

This study has significant limitations, including the use of administrative NIS data. The NIS data comprise the largest database of all-payer U.S. hospitalizations, and this is particularly important for studying ECMO-treated patients, who tend to be younger and not captured in other large, administrative U.S. databases such as Veterans Affairs or Medicare databases. The NIS is also limited in that not every hospital is included in the database. The database is, however, designed to be representative sample of all national inpatient hospitalizations. The NIS database also lacks or incompletely captures some relevant, detailed clinical information including whether patients were placed on venoarterial or venovenous ECMO, case mix based on cannulation strategy, regional variation, or other factors associated with ECMO outcomes such as the RESP score.

In conclusion, ECMO outcomes in the NIS do not follow a traditional volume-outcome relationship. These results suggest ECMO can be performed in properly selected patients with acceptable results in U.S. centers that do not perform a high volume of ECMO. Recent, rapid growth in the number of U.S. ECMO cases and institutions performing ECMO may demonstrate some benefit at high-volume versus medium-volume centers.

Footnotes

Presented at the Sixty-second Annual Meeting of the Southern Thoracic Surgical Association, Orlando, FL, Nov 4–7, 2015.

References

- 1.Hill JD, O’Brien TG, Murray JJ, et al. Prolonged extracorporeal oxygenation for acute post-traumatic respiratory failure (shock-lung syndrome) use of the Bramson membrane lung. N Engl J Med. 1972;286:629–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197203232861204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zapol WM, Snider MT, Hill J, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in severe acute respiratory failure: a randomized prospective study. JAMA. 1979;242:2193–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.242.20.2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy FH, McDermott KM, Kini V, et al. Trends in U.S. extracorporeal membrane oxygenation utilization and outcomes: 2002–2012. Paper presented at 95th annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery; April 25–29, 2015; Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and Economic Assessment of Conventional Ventilatory Support Versus Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation for Severe Adult Respiratory Failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1351–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sidebotham D, McGeorge A, McGuinness S, Edwards M, Willcox T, Beca J. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treating severe cardiac and respiratory disease in adults. Part 1: overview of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;23:886–92. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paden ML, Rycus PT, Thiagarajan RR. ELSO Registry. Update and outcomes in extracorporeal life support. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38:65–70. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauer CM, Yuh DD, Bonde P. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use has increased by 433% in adults in the United States from 2006 to 2011. ASAIO J. 2015;61:31–6. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahn JM, Goss CH, Heagerty PJ, Kramer AA, O’Brien CR, Rubenfeld GD. Hospital volume and the outcomes of mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nallamothu BK, Gurm H, Ting H, et al. Operator experience and carotid stenting outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2011;306:1338–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wennberg DE, Lucas FL, Birkmeyer JD, Bredenberg CE, Fisher ES. Variation in carotid endarterectomy mortality in the Medicare population: trial hospitals, volume, and patient characteristics. JAMA. 1998;279:1278–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.16.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lui C, Grimm JC, Magruder JT, et al. The effect of institutional volume on complications and their impact on mortality after pediatric heart transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1423–31. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shuhaiber J, Isaacs AJ, Sedrakyan A. The effect of center volume on in-hospital mortality after aortic and mitral valve surgical procedures: a population-based study. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100:1340–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karamlou T, Vafaeezadeh M, Parrish AM, et al. Increased extracorporeal membrane oxygenation center case volume is associated with improved extracorporeal membrane oxygenation survival among pediatric patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;145:470–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman CL, Bennett TD, Casper TC, et al. Pediatric and neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: does center volume impact mortality? Crit Care Med. 2014;42:512–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000435674.83682.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Combes A, Brodie D, Bartlett R, et al. Position paper for the organization of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation programs for acute respiratory failure in adult patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:488–96. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0630CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barbaro RP, Odetola FO, Kidwell KM, et al. Association of hospital-level volume of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation cases and mortality: analysis of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:894–901. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1634OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.HCUP Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Healthcare Cost And Utilization Project HCUP: 2002–20012. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maxwell BG, Powers AJ, Sheikh AY, Lee PHU, Lobato RL, Wong JK. Resource use trends in extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in adults: an analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample 1998–2009. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:416–21. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2013.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel NJ, Badheka AO, Jhamnani S, et al. Effect of hospital volume on outcomes of transcatheter mitral valve repair: an early US experience. J Interv Cardiol. 2015;28:464–71. doi: 10.1111/joic.12228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livingston EH, Cao J. Procedure volume as a predictor of surgical outcomes. JAMA. 2010;304:95–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Panageas KS, Schrag D, Riedel E, Bach PB, Begg CB. The effect of clustering of outcomes on the association of procedure volume and surgical outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:658–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-8-200310210-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaja R, Chauhan I, Joshi V, et al. Five-year experience with mobile adult extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a tertiary referral center. J Crit Care. 2015;30:1195–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDermott KM, McCarthy FH, Hoedt A, et al. Shifting admission source and discharge disposition among adult extracorporeal membrane oxygenation patients in the US from 2003 to 2012. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; October 3–7, 2015; Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adalja AA, Watson M, Waldhorn RE, Toner ES. A conceptual approach to improving care in pandemics and beyond: severe lung injury centers. J Crit Care. 2013;28:318e9–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]