Abstract

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering skin disorder. Recently, BP induced by dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors has been a concern. Although DPP‐4 inhibitors are commonly used in the Asian population because of their safety and efficacy, BP associated with DPP‐4 inhibitors is sometimes seen in clinical settings. Here, we report five Japanese cases of BP associated with the agents. In the present cases, BP occurred in older adults using four different DPP‐4 inhibitors, which showed various clinical manifestations in terms of latency period for BP, sex, glycemic control and diabetes duration. Withdrawal of DPP‐4 inhibitors was effective in improving BP, and achieved remission even in cases requiring oral steroid administration and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Clinicians should note the importance of early diagnosis of this clinical condition and initiate prompt withdrawal of DPP‐4 inhibitors.

Keywords: Bullous pemphigoid, Dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors, Elderly

Introduction

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an autoimmune blistering skin disorder, in which a majority of autoantibodies targets the extracellular non‐collagenous 16A domain (NC16A) of hemidesmosomal collagen XVII1. Of drug‐induced BP, BP associated with dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 (DPP‐4) inhibitors, which are known as gliptins, has attracted attention because of the higher incidence of the adverse effect in comparison with other drugs2. As DPP‐4 inhibitors are the most commonly used therapy in the Asian population because of their safety and efficacy3, BP associated with DPP‐4 inhibitors should be widely recognized as an adverse event in clinical settings. Here, we report five cases of DPP‐4 inhibitors‐induced BP in Japanese type 2 diabetes mellitus patients, which occurs mainly in the elderly. The present cases showed that BP associated with DPP‐4 inhibitors exhibits various manifestations and the importance of prompt withdrawal of the agents.

Case presentation

Case 1

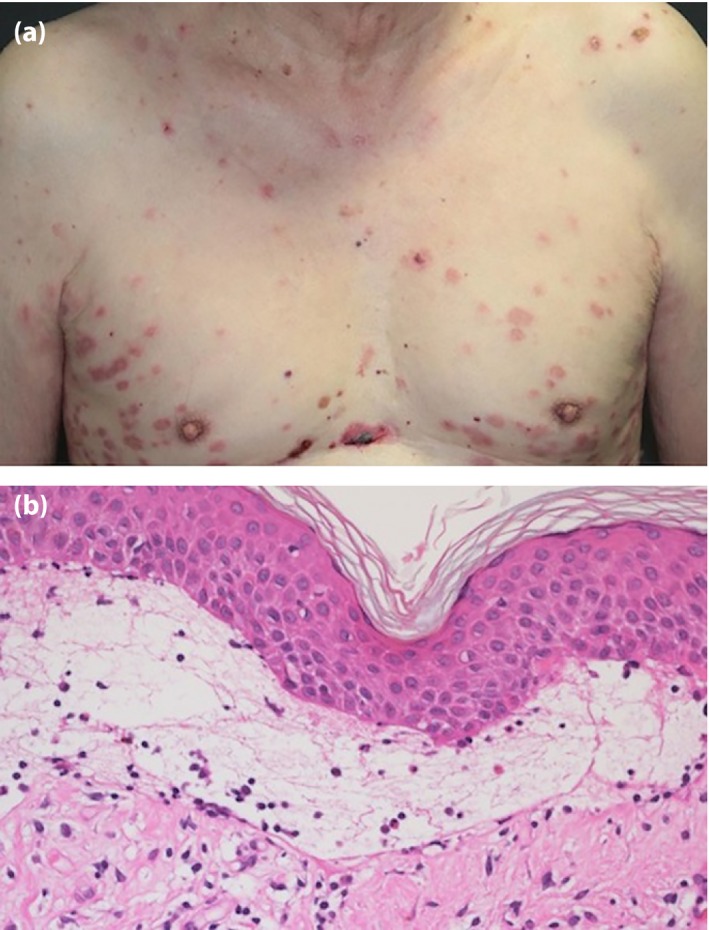

An 81‐year‐old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with erythematous tense bullae, which initially appeared on his thigh and gradually spread over his whole body (Figure 1a). No mucosal involvement was found. Linagliptin was introduced 9 months before the onset of skin lesions. Histological findings showed a subepidermal blister, and direct immunofluorescence analysis showed a linear staining pattern with complement C3 and immunoglobulin G at the basement membrane (Figure 1b). Enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay for BP180‐NC16A was positive. The diagnosis of BP was made, and he was started on 20 mg/day prednisolone. Linagliptin was later suspected as a cause of BP. Remission was achieved after withdrawal of linagliptin, which was replaced by insulin. He had sustained remission even while prednisolone was tapered.

Figure 1.

Disseminated bullous eruption with erythema in case 1. (a) Macroscopic observation. (b) Microscopic observation of the skin (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×20).

Case 2

An 86‐year‐old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with erythematous tense bullae on her back, which later speared to her entire body. Linaglitpin was introduced 9 months before the onset of skin lesions. The diagnosis of BP was made pathologically. The patient was started on 20 mg/day prednisolone, which was tapered to 2 mg/day over 10 months. However, tense bullae reappeared and the prednisolone dosage was increased again. At this point, linagliptin was suspected as the cause of BP and was discontinued. After switching linagliptin to dulaglutide, remission was achieved.

Case 3

An 83‐year‐old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus was treated with linagliptin for 10 months and then switched to sitagliptin, with which she was treated for an additional 15 months before erythematous tense bullae appeared. Clinical diagnosis of BP was confirmed pathologically. The patient was initially treated with prednisolone (15 mg/day), which was replaced by intravenous immunoglobulin therapy after 3 days because of poor control of BP. The skin lesions diminished consistently after switching from linagliptin to insulin.

Case 4

An 86‐year‐old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with vildagliptin for 6 months presented with erythematous tense bullae. The clinical diagnosis of BP was confirmed pathologically. She was started with 40 mg/day prednisolone and then received intravenous immunoglobulin due to poor control of skin symptoms. After switching vildagliptin to insulin, remission was achieved.

Case 5

A 63‐year‐old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus treated with anagliptin for 5 months presented with erythematous bullous eruptions on his entire body. The clinical diagnosis of BP was confirmed pathologically. The patient was started on prednisolone (20 mg/day). Anagliptin was switched to repaglinide. Prednisolone was tapered and stopped within 14 days. Remission of skin lesions was observed.

Discussion

Bullous pemphigoid has been classically associated with certain medications, including diuretics, beta‐blockers and antibiotics4. Recently, DPP‐4 inhibitors, also called gliptins, were reported as another causative agent for BP. Although the pathogenic mechanism of DPP‐4 inhibitors‐provoked BP remains unclear, this adverse drug reaction is reported with multiple gliptins, suggesting a class effect2, 5. Actually, the present cases included four of these agents; linagliptin, sitagliptin, vildagliptin and anagliptin. To our best knowledge, case 5 is the first report of anagliptin‐induced BP. All of the present cases showed persistent cutaneous symptoms despite steroid administrations. Improvement was seen within 2 weeks after cessation of DPP‐4 inhibitors, and sustained remissions were achieved within 2 months (Table 1). These findings strongly indicate the causal involvement of DPP‐4 inhibitors. The World Health Organization‐Uppsala Monitoring Center criteria for standardized causality assessment also indicate reasonable causalities in our cases6.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the present cases

| Patient | Age (years)/sex | HbA1c levels at BP diagnosis (%) | DPP‐4 inhibitor | Latency (months) | Titers of BP180NC16A ELISA (U/mL) | Complete remission from agent withdrawal (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 81/Male | 7.6 | Linagliptin | 9 | 434 | 6 |

| Case 2 | 86/Male | 7.4 | Linagliptin | 9 | 303 | 4 |

| Case 3 | 83/Female | 6.8 | Linagliptin, Sitagliptin | 25 | 2110 | 2 |

| Case 4 | 86/Female | 6.3 | Vildagliptin | 6 | 182 | 4 |

| Case 5 | 63/Male | 7.3 | Anagliptin | 5 | 305 | 2 |

BP, bullous pemphigoid; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; ELISA, enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

Two retrospective analyses of pharmacovigilance databases were recently published from Europe2, 7. One of the studies showed no clear relationship between the onset of BP and clinical presentations, such as allergic history, diabetes duration, diabetic complications, glycemic control and concomitant medications or sex2. The mean age of BP onset was relatively old (74 years), and the latency period for BP from introduction of DPP‐4 inhibitors was relatively long (10 months)2. In the present cases, the age also tended to be older, while the mean time from DPP‐4 inhibitor administration to BP onset varied from 5 to 25 months.

A recent study noted BP associated with DPP‐4 inhibitors might present non‐inflammatory skin symptoms and negative autoantibodies against BP180‐NC16A, which differs from conventional BP8. However, all of the present cases involved evident erythema and positive autoantibodies against BP180‐NC16A, which could indicate that there is a variety of skin inflammations of BP pathologically associated with the various DPP‐4 inhibitors. Thus, further investigations including a large‐scale epidemiological study are required to determine the clinical characteristics of DPP‐4 inhibitors‐associated BP.

The present cases also showed the difficulty of diagnosis for DPP‐4 inhibitors‐associated BP, which is due to the various clinical manifestations, especially in terms of latency period. As these features could mask the possible involvement of DPP‐4 inhibitors in BP, clinicians should be fully aware of the potential risk. The present cases show the importance of early diagnosis and prompt withdrawal of the agents to avoid exacerbation of skin symptoms and administration of intravenous immunoglobulin or high‐dose steroid, which often results in poor glycemic control. As it took at least 2 weeks to achieve complete remission, appropriate withdrawal of the agents is required for remission of BP in suspected cases.

The rising aging population and use of combination drug therapy including DPP‐4 inhibitors requires heightened awareness of DPP‐4 inhibitors‐induced BP. Once BP has occurred by DPP‐4 inhibitors, appropriate options of antidiabetic agents in the elderly are limited9, 10. However, in the present cases, we successfully switched DPP‐4 inhibitors to insulin, glinide or a glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist. Any drug, except DPP‐4 inhibitors, can be selected, while paying attention to hypoglycemia.

In summary, the present cases showed various clinical manifestations of DPP‐4 inhibitors‐induced BP in terms of latency period, agents and cutaneous inflammations. The importance of early diagnosis of the adverse event should be emphasized, as the prompt withdrawal of the agent was effective for improvement of BP.

Disclosure

SH has received honoraria for speaking from MSD, Eli Lilly and Tanabe Mitsubishi Pharma. DY has received consulting and/or speaker fees from Novo Nordisk. DY also received clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Taisho‐Toyama. MSD, Takeda, Ono and Novo Nordisk Pharma. MO has received a clinical commissioned/joint research grant from Takeda. NI has received clinical commissioned/joint research grants from Mitsubishi Tanabe, AstraZeneca, Astellas and Novartis Pharma, and scholarship grants from Takeda, MSD, Ono, Sanofi, Japan Tobacco Inc., Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Kyowa Kirin, Astellas, Daiichi‐Sankyo and Taisho‐Toyama Pharma.

J Diabetes Investig 2018;9: 445–447

The first two authors (SY and TM) contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1. Stanley JR. Pemphigus and pemphigoid as paradigms of organ‐specific, autoantibody‐mediated diseases. J Clin Invest 1989; 83: 1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Béné J, Moulis G, Bennani I, et al Bullous pemphigoid and dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors: A case–noncase study in the French Pharmacovigilance Database. Br J Dermatol 2016; 175: 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mu YM, Misra A, Adam JM, et al Managing diabetes in Asia: Overcoming obstacles and the role of DPP‐IV inhibitors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012; 95: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vassileva S. Drug‐induced pemphigoid: Bullous and cicatricial. Clin Dermatol 1998; 16: 379–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sakai A, Shimomura Y, Ansai O, et al Linagliptin‐associated bullous pemphigoid that was most likely caused by IgG autoantibodies against the midportion of BP180. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 541–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization Uppsala Monitoring Centre . The Use of the WHO‐UMC System for Standardized Case Causality Assessment [Monogram on the Internet]. Available from: https://www.who-umc.org/media/2768/standardised-case-causality-assessment.pdf.

- 7. García M, Aranburu MA, Palacios‐Zabalza I, et al Dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV inhibitors induced bullous pemphigoid: A case report and analysis of cases reported in the European pharmacovigilance database. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016; 41: 368–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Izumi K, Nishie W, Mai Y, et al Autoantibody profile differentiates between inflammatory and noninflammatory bullous pemphigoid. J Invest Dermatol 2016; 136: 2201–2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Japan Diabetes Society (JDS)/Japan Geriatrics Society (JGS) Joint Committee on Improving Care for Elderly Patients with Diabetes . Committee Report: Glycemic targets for elderly patients with diabetes. J Diabetes Investig 2017; 8: 126–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kojima T, Mizukami K, Tomita N, et al Report of the committee: Screening tool for older persons’ appropriate prescriptions in Japanese (STOPP‐J) – Report of the Japan Geriatrics Society Working Group on “guidelines for medical treatment and its safety in the elderly”. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2016; 16: 983–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]