Abstract

The Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS) has been shown to be associated with survival rates in patients with advanced cancer. The present study aimed to compare the GPS with the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) in patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding. For the investigation, a total of 384 gastric patients with peritoneal metastasis were retrospectively analyzed. Patients with elevated C-reactive protein (CRP; >10 mg/l) and hypoalbuminemia (<35 mg/l) were assigned a score of 2. Patients were assigned a score of 1 if presenting with only one of these abnormalities, and a score of 0 if neither of these abnormalities were present. The clinicopathologic characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients with peritoneal seeding were analyzed. The results showed that the median overall survival (OS) of patients in the GPS 0 group was longer, compared with that in the GPS 1 and GPS 2 groups (15.50, vs. 10.07 and 7.97 months, respectively; P<0.001). No significant difference was found between the median OS of patients with a good performance status (ECOG <2) and those with a poor (ECOG ≥2) performance status (13.67, vs. 11.80 months; P=0.076). In the subgroup analysis, the median OS in the GPS 0 group was significantly longer, compared with that in the GPS 1 and GPS 2 groups, for the patients receiving palliative chemotherapy and patients without palliative chemotherapy. Multivariate survival analysis demonstrated that CA19-9, palliative gastrectomy, first-line chemotherapy and GPS were the prognostic factors predicting OS. In conclusion, the GPS was superior to the subjective assessment of ECOG PS as a prognostic factor in predicting the outcome of gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding.

Keywords: gastric cancer, peritoneal seeding, Glasgow Prognostic Score, performance status

Introduction

Gastric cancer remains the second most common type of malignant cancer in China, despite the incidence decreasing worldwide (1,2). In addition, the majority of patients with gastric cancer in China are diagnosed with late-stage gastric cancer (3).

Among the patterns of metastasis, peritoneal seeding is the most common and most life-threatening type of gastric cancer, and is considered to be the terminal stage of gastric cancer (4). Despite often short and poor survival rates among patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding, there exists a marked heterogeneity in the survival duration. Therefore, there has been increasing interest in investigating the prognostic factors and allowing more accurate stratification for the patients, which are likely to improve clinical practice and possibly contribute to more rational study design and analysis.

The assessment of performance status as the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) is a simple tool to evaluate a patient's physical condition and is also a common prognostic factor predicting treatment survival rates (5). However, the ECOG PS assessment is subjective and biased. Ando et al reported that performance status assessments differed significantly among oncologists, nurses and patients, with the assessment by oncologists being most optimistic and that by patients the least (6). Therefore, the selection of ECOG PS as a prognostic factor remains problematic, and more objective and reliable prognostic scores are required to reflect clinical outcome in patients with advanced cancer.

There is increasing evidence that the systemic inflammatory response, as evidenced by the elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP), is critical in patients with advanced cancer (7,8). Furthermore, Forrest et al reported that the Glasgow Prognostic Score (GPS), the combination of serum CRP and serum albumin, was a reliable, objective scoring tool for predicting survival rates in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer (9). Additionally, several studies have demonstrated that GPS is associated with prognosis independent of age, stage and performance status in various types of malignancy (10–16).

Crumley et al reported that the GPS was superior to performance status as a prognostic factor in patients receiving palliative chemotherapy for gastroesophageal cancer (10). However, whether GPS is a superior prognostic factor to ECOG PS in predicting the survival rates of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding remains to be elucidated. Therefore, the present study aimed to compare GPS with ECOG PS in predicting the outcome of gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding.

Patients and methods

Patients

Between May 2006 and March 2014, the present study recruited 384 consecutive patients, who were diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma with peritoneal seeding, at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center. The treatment, including gastrectomy, was performed following the provision of written informed consent from patients. The present study was approved by the independent Institute Research Ethics Committee at the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (Guangdong, China) and was performed according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

The demographic information of the patients was collected for analysis. Only patients with an entire set of laboratory data were included in the present study. Patients who had evidence of infection, and those who received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy were excluded.

The ECOG PS was evaluated by the definition of the ECOG criteria. Peritoneal seeding was classified according to the first English edition of the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma (17). Multisite distant metastasis was defined as concurrent extra-regional lymph node metastasis, hepatic metastasis, lung metastasis or other metastases excluding peritoneal seeding. The first-line chemotherapy regimens included various agents, including 5-fluorouracil, taxane, irinotecan, oxaliplatin and capecitabine.

GPS estimation

The GPS was estimated according to a previous description (9). The patients were assigned a score of 2 if they presented with elevated CRP (>10 mg/l) and hypoalbuminemia (<35 mg/l), a score of 1 if presenting with only one of these biochemical abnormalities, and a score of 0 if neither of these abnormalities were present.

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages, and were compared using χ2 tests. Unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to compare differences in overall survival (OS) between different groups with log-rank testing. Prognostic factors were first analyzed by univariate analysis, with which P<0.05 was entered into multivariate analysis using Cox proportional hazard models. The forward selection method was used for multivariate Cox proportional analysis. In the present study, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were also constructed to assess sensitivity, specificity and areas under the curves (AUCs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). P<0.05 (two-sided) was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. The statistical analyses described above were performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The patients were monitored every 3 months for 2 years, and at intervals of 6–12 months thereafter until lost to follow up or mortality. The regular follow-up period ranged between 0.1 and 52.2 months (median, 9.77 months).

Results

Patient characteristics

The classified clinical and laboratory characteristics of the 384 gastric cancer patients with peritoneal seeding are shown in Table I. There were no significant differences in OS in terms of gender (male/female), ECOG PS (<2/≥2) (Fig. 1), tumor location (cardia/middle/antrum), signet ring cell carcinoma (yes/no), or CA72-4 (<5.3/≥5.3 U/ml). By contrast, significant differences in OS were observed in terms of age, tumor size, ascites, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA19-9, albumin, CRP, peritoneal seeding classification, multisite distant metastasis, palliative gastrectomy, first-line chemotherapy and GPS (Fig. 2).

Table I.

Classified clinical and laboratory characteristics associated with OS.

| Characteristic | Patients (n) | OS (months), median (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.019 | ||

| <65 | 319 | 14.03 (12.07–16.00) | |

| ≥65 | 65 | 10.37 (6.78–13.96) | |

| Gender (n) | 0.285 | ||

| Male | 210 | 12.23 (9.94–14.53) | |

| Female | 174 | 13.70 (11.99–15.41) | |

| ECOG PS (n) | 0.076 | ||

| <2 | 285 | 13.67 (11.39–15.94) | |

| ≥2 | 99 | 11.80 (9.40–14.20) | |

| Tumor location | 0.514 | ||

| Cardia | 96 | 11.73 (8.78–14.69) | |

| Middle | 142 | 13.13 (10.07–16.20) | |

| Antrum | 138 | 14.23 (11.37–17.10) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.038 | ||

| <5 | 150 | 14.27 (10.83–17.71) | |

| ≥5 | 202 | 11.27 (8.72–13.81) | |

| SRCC | 0.052 | ||

| Yes | 136 | 15.83 (12.19–19.47) | |

| No | 244 | 11.77 (9.51–14.02) | |

| Ascites | 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 160 | 9.73 (8.21–11.25) | |

| No | 224 | 15.73 (13.01–18.46) | |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 0.005 | ||

| <5 | 270 | 14.50 (12.90–16.10) | |

| ≥5 | 101 | 9.80 (7.27–12.33) | |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | <0.001 | ||

| <35 | 223 | 15.50 (12.76–18.25) | |

| ≥35 | 141 | 10.90 (7.95–13.86) | |

| CA72-4 (U/ml) | 0.125 | ||

| <5.3 | 161 | 14.00 (11.55–16.46) | |

| ≥5.3 | 154 | 12.10 (8.82–15.38) | |

| Albumin (g/l) | 0.001 | ||

| <35 | 63 | 8.97 (7.51–10.42) | |

| ≥35 | 321 | 14.03 (12.34–15.73) | |

| CRP (mg/l) | <0.001 | ||

| <10 | 274 | 14.57 (12.80–16.34) | |

| ≥10 | 110 | 8.73 (7.30–10.17) | |

| Peritoneal seeding | 0.001 | ||

| P1/P2 | 200 | 15.47 (13.73–17.20) | |

| P3 | 184 | 10.00 (8.64–11.36) | |

| Multisite distant metastasis | 0.002 | ||

| Yes | 142 | 10.17 (7.75–12.59) | |

| No | 241 | 15.47 (12.66–18.27) | |

| Palliative gastrectomy | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 164 | 19.10 (15.85–22.35) | |

| No | 219 | 9.80 (8.31–11.29) | |

| First-line chemotherapy | <0.001 | ||

| Yes | 279 | 15.40 (13.70–17.10) | |

| No | 105 | 6.40 (4.66–8.14) | |

| GPS | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 247 | 15.50 (13.09–17.91) | |

| 1 | 101 | 10.07 (8.29–11.84) | |

| 2 | 36 | 7.97 (6.47–9.46) |

GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; SRCC, signet ring cell carcinoma; CEA, baseline carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9, baseline carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CA72-4 baseline carbohydrate antigen 72-4; CRP, C-reactive protein.

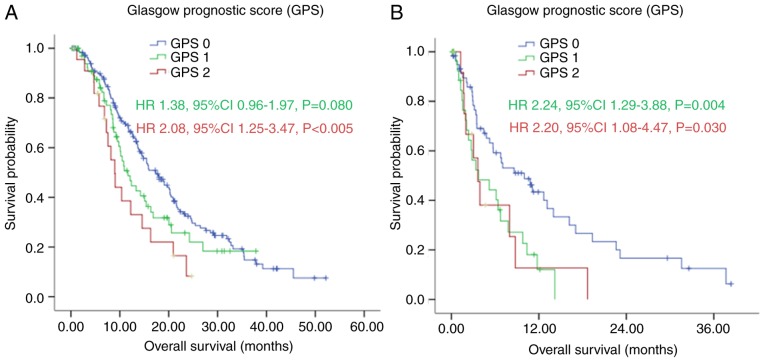

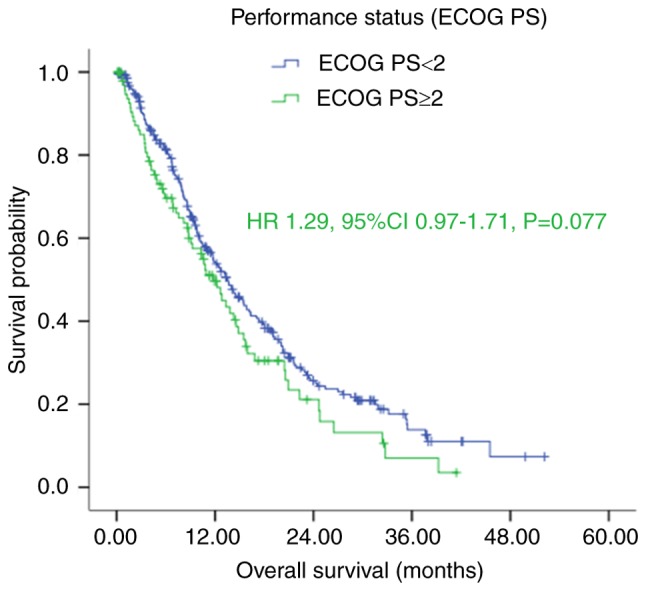

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding according to ECOG PS (P=0.077). P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

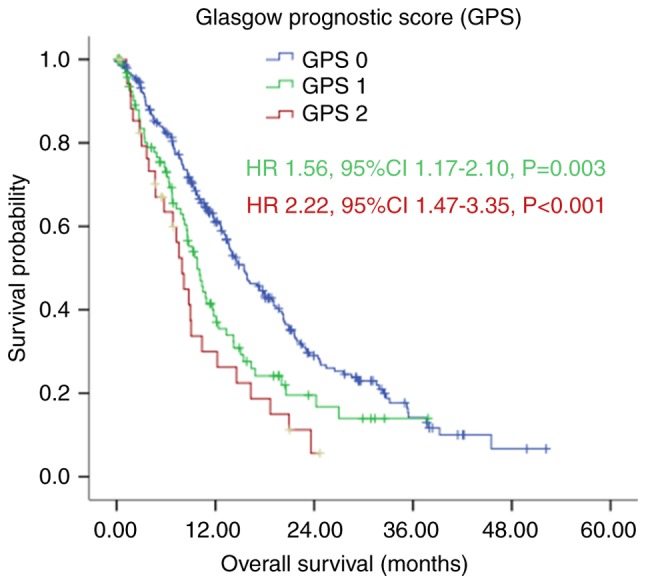

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding according to GPS (P<0.001). P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score.

The associations between clinicopathological characteristics and GPS in patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding are shown in Table II. Age, gender, ascites, CA72-4, albumin, CRP, classification of peritoneal seeding, multisite distant metastasis and palliative gastrectomy were closely associated with the GPS classification. Compared with the GPS 0 and GPS 1 patients, the GPS 2 patients appeared to have higher levels of tumor marker and CRP, and had a higher frequency of ascites and multisite distant metastasis with more severe peritoneal seeding.

Table II.

Clinicopathlogical characteristics of 384 patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis according to GPS.

| Characteristic | GPS 0 (%) | GPS 1 (%) | GPS 2 (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 247 (64.3) | 101 (26.3) | 36 (9.4) | |

| Age (years) | 0.020 | |||

| <65 | 215 (87.0) | 77 (76.2) | 27 (75.0) | |

| ≥65 | 32 (13.0) | 24 (23.8) | 9 (25.0) | |

| Gender (n) | 0.010 | |||

| Male | 121 (49.0) | 65 (64.4) | 24 (66.7) | |

| Female | 126 (51.0) | 36 (35.6) | 12 (33.3) | |

| ECOG PS (n) | 0.131 | |||

| <2 | 191 (77.3) | 71 (70.3) | 23 (63.9) | |

| ≥2 | 56 (22.7) | 30 (29.7) | 13 (36.1) | |

| Tumor location | 0.636 | |||

| Cardia | 66 (27.4) | 23 (23.2) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Middle | 89 (36.9) | 36 (36.4) | 17 (47.2) | |

| Antrum | 86 (35.7) | 40 (40.4) | 12 (33.3) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.102 | |||

| <5 | 105 (46.3) | 36 (38.7) | 9 (28.1) | |

| ≥5 | 122 (53.7) | 57 (61.3) | 23 (71.9) | |

| SRCC | 0.234 | |||

| Yes | 156 (63.4) | 61 (61.6) | 27 (77.1) | |

| No | 90 (36.6) | 38 (38.4) | 8 (22.9) | |

| Ascites | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 167 (67.6) | 47 (46.5) | 10 (27.8) | |

| No | 80 (32.4) | 54 (53.5) | 26 (72.2) | |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 0.114 | |||

| <5 | 181 (75.7) | 70 (70.0) | 19 (59.4) | |

| ≥5 | 58 (24.3) | 30 (30.0) | 13 (40.6) | |

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | 0.715 | |||

| <35 | 147 (62.8) | 58 (58.6) | 18 (58.1) | |

| ≥35 | 87 (37.2) | 41 (41.4) | 13 (41.9) | |

| CA72-4 (U/ml) | 0.006 | |||

| <5.3 | 116 (56.9) | 37 (45.1) | 8 (27.6) | |

| ≥5.3 | 88 (43.1) | 45 (54.9) | 21 (72.4) | |

| Albumin (g/l) | <0.001 | |||

| <35 | 0 (0.0) | 27 (26.7) | 36 (100.0) | |

| ≥35 | 247 (100.0) | 74 (73.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| CRP (mg/l) | <0.001 | |||

| <10 | 247 (100.0) | 74 (73.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ≥10 | 0 (0.0) | 27 (26.7) | 36 (100.0) | |

| Peritoneal seeding | 0.001 | |||

| P1/P2 | 145 (58.7) | 44 (43.6) | 11 (30.6) | |

| P3 | 102 (41.3) | 57 (56.4) | 25 (69.4) | |

| Multisite distant metastasis | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 75 (30.5) | 55 (54.5) | 12 (33.3) | |

| No | 171 (69.5) | 46 (45.5) | 24 (66.7) | |

| Palliative gastrectomy | 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 122 (49.6) | 32 (31.7) | 10 (27.8) | |

| No | 124 (50.4) | 69 (68.3) | 26 (72.2) | |

| First-line chemotherapy | 0.242 | |||

| Yes | 186 (75.3) | 70 (69.3) | 23 (63.9) | |

| No | 61 (24.7) | 31 (30.7) | 13 (36.1) |

GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; SRCC, signet ring cell carcinoma; CEA, baseline carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9, baseline carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CA72-4 baseline carbohydrate antigen 72-4; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Survival rates

The results of the Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that patients with good performance status (ECOG <2) had longer median OS, compared with those with poor performance status (ECOG ≥2), with an OS of 13.67 (95% CI: 11.39–15.94), vs. 11.80 (95% CI: 9.40–14.20) months, respectively. However, this difference was not significant (P=0.076; Fig. 1 and Table I).

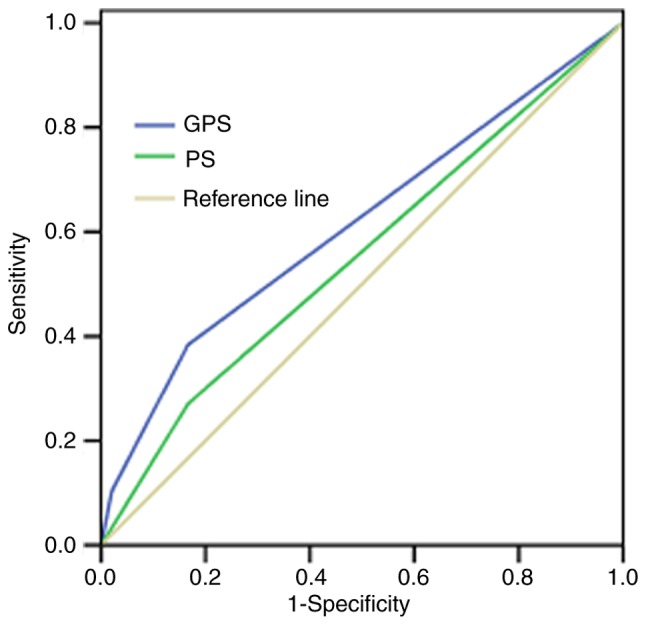

However, the Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrated that patients in the GPS 0 group had a significantly longer median OS, compared with those in the GPS 1 and GPS 2 group, with median OS rates of 15.50 (95% CI: 13.09–17.91), 10.07 (95% CI: 8.29–11.84) and 7.97 (95% CI: 6.47–9.46) months, respectively (P<0.001; Fig. 2 and Table I). The ROC curves also showed that the AUC of GPS was 0.613 (P=0.011), whereas the AUC of ECOG PS was 0.552 (P=0.243; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristics curves of GPS and ECOG PS of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding. The AUC of GPS was 0.613 (P=0.011), the AUC of ECOG PS was 0.552 (P=0.243). GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; AUC, area under the curve.

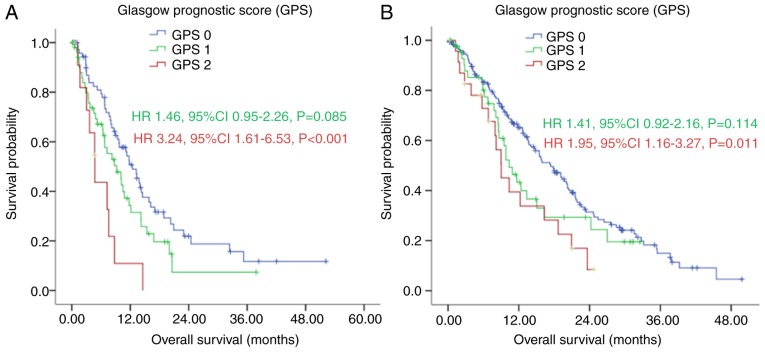

In the subgroup analysis, with first-line chemotherapy, the median OS of patients in the GPS 0 group was significantly longer, compared with the median OS of patients in the GPS 1 and GPS 2 group [17.40 (95% CI: 14.47–20.33), vs. 11.67 (95% CI: 8.50–14.84), vs. 8.97 (95% CI: 7.20–10.73) months, respectively], as shown in Fig. 4A (P=0.008). Without first-line chemotherapy, patients in the GPS 0 group also had a significantly longer median OS, compared with those in the GPS 1 and GPS 2 groups [10.00 (95% CI: 5.05–14.95), vs. 3.73 (95% CI: 0.00–7.58), vs. 3.63 (95% CI: 2.30–4.97) months, respectively], as shown in Fig. 4B (P=0.005).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding according to GPS stratified by first-line chemotherapy. (A) With first-line chemotherapy (P=0.008); (B) without first-line chemotherapy (P=0.005). P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score.

In patients with multisite distant metastasis, the median OS of the GPS 0 group was longer, compared with the median OS in the GPS 1 and GPS 2 group [12.43 (95% CI: 9.75–15.12), vs. 9.20 (95% CI: 5.75–12.65), vs. 4.73 (95% CI: 3.07–6.40) months (Fig. 5A; P=0.002). Without multisite distant metastasis, the GPS 0 group also had a longer median OS, compared with the median OS in the GPS 1 and GPS 2 groups [17.40 (95% CI: 14.12–20.68), vs. 10.37 {95% CI: 7.97–12.76), vs. 9.03 (95% CI: 6.12–11.95) months, as shown in Fig. 5B (P=0.019).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding according to GPS stratified by multisite distant metastasis. (A) With multisite distant metastasis (P=0.002); (B) without multisite distant metastasis (P=0.019). P-values were calculated using the log-rank test. GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

In the univariate survival analysis, age (P=0.020), tumor size (P=0.039), ascites (P<0.001), CEA (P=0.006), CA19-9 (P<0.001), albumin (P=0.001), CRP (P<0.001), classification of peritoneal seeding (P=0.001), multisite distant metastasis (P=0.002), palliative gastrectomy (P<0.001), first-line chemotherapy (P<0.001) and GPS (P<0.001) were associated with OS (Table III). The multivariate survival analysis demonstrated that CA19-9 (P<0.001), palliative gastrectomy (P<0.001), first-line chemotherapy (P<0.001) and GPS (P<0.001) remained the prognostic factors in predicting the OS (Table III).

Table III.

Univariate and multivariate of analyses of overall survival in patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis.

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95%CI) | P-value | HR (95%CI) | P-value |

| Age (years) | 0.020 | |||

| <65 | 1 | |||

| ≥65 | 1.44 (1.60–1.96) | |||

| Gender (n) | 0.285 | |||

| Male | 1 | |||

| Female | 0.87 (0.68–1.12) | |||

| ECOG PS (n) | 0.077 | |||

| <2 | 1 | |||

| ≥2 | 1.29 (0.97–1.71) | |||

| Tumor location | 0.515 | |||

| Cardia | 1 | |||

| Middle | 1.07 (0.77–1.47) | 0.696 | ||

| Antrum | 0.90 (0.65–1.25) | 0.536 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.039 | |||

| <5 | 1 | |||

| ≥5 | 1.32 (1.01–1.71) | |||

| SRCC | 0.053 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 0.77 (0.59–1.00) | |||

| Ascites | <0.001 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.53 (1.19–1.97) | |||

| CEA (ng/ml) | 0.006 | |||

| <5 | 1 | |||

| ≥5 | 1.47 (1.12–1.93) | |||

| CA19-9 (U/ml) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| <35 | 1 | 1 | ||

| ≥35 | 1.62 (1.25–2.10) | 1.63 (1.25–2.12) | ||

| CA72-4 (U/ml) | 0.126 | |||

| <5.3 | 1 | |||

| ≥5.3 | 1.24 (0.94–1.62) | |||

| Albumin (g/l) | 0.001 | |||

| <35 | 1 | |||

| ≥35 | 0.59 (0.43–0.82) | |||

| CRP (mg/l) | <0.001 | |||

| <10 | 1 | |||

| ≥10 | 1.72 (1.30–2.27) | |||

| Peritoneal seeding | 0.001 | |||

| P1/P2 | 1 | |||

| P3 | 1.50 (1.17–1.92) | |||

| Multisite distant metastasis | 0.002 | |||

| No | 1 | |||

| Yes | 1.49 (1.15–1.93) | |||

| Palliative gastrectomy | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.51 (0.40–0.66) | 0.56 (0.43–0.73) | ||

| First-line chemotherapy | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 0.43 (0.32–0.57) | 0.40 (0.30–0.54) | ||

| GPS | <0.001 | 0.006 | ||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | 1.56 (1.17–2.10) | 0.003 | 1.47 (1.08–1.98) | 0.013 |

| 2 | 2.22 (1.47–3.35) | <0.001 | 1.76 (1.13–2.73) | 0.012 |

GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; SRCC, signet ring cell carcinoma; CEA, baseline carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9, baseline carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CA72-4 baseline carbohydrate antigen 72-4; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Discussion

There is substantial evidence that tumor-related factors and host-related factors, including poor performance status, weight loss and systemic inflammatory response, can determine the outcomes of patients with malignant cancer (15,18). However, the assessments of weight loss and performance status are subjective and biased. By contrast, in the present study, univariate and multivariate analysis demonstrated that an inflammatory prognostic score, as evidenced by the GPS, was superior to performance status (ECOG PS) as a prognostic factor in predicting the outcome of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal dissemination.

It is generally recognized that cancer-related inflammation can assist in malignant cancer cell proliferation and survival, accelerating angiogenesis and metastasis, destroying the adaptive immune responses of the patients, and finally altering the responses of patients to hormones and chemotherapy treatment (19). CRP is an important acute phase protein and a sensitive marker of the systemic inflammatory response. Additionally, CRP can be expressed in malignant cancer cells (7,20,21). CRP synthesis is generally induced by several chemokines and cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6, from the liver or cancer tissues (22,23). However, serum CRP measurement is more convenient and stable, compared with cytokine and chemokine measurement. Several studies have revealed that elevated CRP is associated with poor survival rates in certain types of malignant cancer, including breast cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma and gastric cancer (8,24,25). In accordance with other studies (8,24), the present study showed that elevated CRP correlated with poorer prognosis in patients with gastric cancer and peritoneal seeding.

Lien et al reported that preoperative serum albumin levels are associated with resectability and survival rates in patients with gastric cancer (26). Serum albumin is not only an indicator used to recognize the nutritional status of patients, but is also useful for predicting the prognostic outcome of cancer patients (5,27). Patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding often develop hypoalbuminemia due to oral intake deficiency, overconsumption, bleeding and ascites. In the present study, univariate analysis revealed that hypoalbuminemia was significantly associated with poor prognosis. However, when CRP and albumin were placed in the multivariate analysis, neither of them was associated with OS, which indicated the insufficiency of serum CRP and albumin alone as a prognostication. Therefore, GPS, the combination of serum albumin and CRP, was superior in predicting the outcome of gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding.

The mechanism by which GPS affect cancer survival rates remains to be fully elucidated. However, in addition to reflecting the presence of a systemic inflammatory response, GPS may also reflect the declining nutrition status of patients with advanced stage disease, which affects their tolerance and compliance to therapeutic regimens (10). In the present study, it was also noted that a higher GPS correlated significantly with higher levels of tumor markers, increased frequency of ascites, multisite distant metastasis and more severe peritoneal seeding, suggesting that a higher GPS was correlated with a more aggressive disease phenotype. However, certain therapeutic regimes can lead to elevated CRP or weight loss and malnourishment, and thus reduced albumin levels. Therefore, whether the poorer survival rate of patients was due to these host-associated factors or cancer-associated factors also remains to be elucidated. Of note, the present study found that there were no significant differences among the GPS 0, GPS 1 and GPS 2 groups regarding the period of first-line chemotherapy and response to chemotherapy (Table IV), which was a contradiction to the findings of other studies (12,20). This suggested that patients with a higher GPS should also receive active palliative chemotherapy. Although anti-inflammatory treatment with low-dose aspirin lowers the incidence of colorectal adenomas and the mortality rate of several common types of cancer (28,29), whether anti-inflammatory treatment can improve the outcome of patients with advanced cancer remains to be elucidated. Furthermore, whether a higher GPS is a cause or a consequence of cancer progression also remains unclear.

Table IV.

Response to chemotherapy of 278 patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis according to GPS.

| Characteristic | GPS 0 | GPS 1 | GPS 2 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 185 | 70 | 23 | |

| Period of chemotherapy, mean (n, 95% CI) | 5.39 (4.82–5.97) | 5.06 (4.14–5.97) | 4.96 (3.58–6.33) | 0.762 |

| DCR (CR+PR+SD) n (%) | 48 (25.9) | 19 (27.1) | 3 (13) | 0.368 |

GPS, Glasgow Prognostic Score; DCR, disease control rate; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; CI, confidence interval.

Irrespective of the mechanisms involved, the results of the present study showed that GPS was a simple, objective and reliable survival predictor for gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding, which was true for those receiving palliative chemotherapy and for those who were not.

The present study was a substantially retrospective study, which is a potential limitation. Although the data in the present study were from a high-volume institution, the results require cautious interpretation and a large-scale prospective study is required to validate the results.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that the GPS is superior to performance status (ECOG PS) as a prognostic factor in predicting the outcome of patients with gastric cancer with peritoneal seeding.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81302144) and the Guangdong Science and Technology Department (grant no. 2012B0617000879).

References

- 1.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S, Li YF, Feng XY, Zhou ZW, Yuan XH, Chen YB. Significance of palliative gastrectomy for late-stage gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2012;106:862–871. doi: 10.1002/jso.23158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bando E, Yonemura Y, Takeshita Y, Taniguchi K, Yasui T, Yoshimitsu Y, Fushida S, Fujimura T, Nishimura G, Miwa K. Intraoperative lavage for cytological examination in 1,297 patients with gastric carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1999;178:256–262. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachlova M, Majek O, Tucek S. Prognostic value of scores based on malnutrition or systemic inflammatory response in patients with metastatic or recurrent gastric cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:1362–1370. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.956261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ando M, Ando Y, Hasegawa Y, Shimokata K, Minami H, Wakai K, Ohno Y, Sakai S. Prognostic value of performance status assessed by patients themselves, nurses, and oncologists in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1634–1639. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nozoe T, Korenaga D, Futatsugi M, Saeki H, Maehara Y, Sugimachi K. Immunohistochemical expression of C-reactive protein in squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus-significance as a tumor marker. Cancer Lett. 2003;192:89–95. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00630-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto K, Ikeda Y, Korenaga D, Tanoue K, Hamatake M, Kawasaki K, Yamaoka T, Iwatani Y, Akazawa K, Takenaka K. The impact of preoperative serum C-reactive protein on the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:1856–1864. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forrest LM, McMillan DC, McArdle CS, Angerson WJ, Dunlop DJ. Evaluation of cumulative prognostic scores based on the systemic inflammatory response in patients with inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1028–1030. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crumley AB, McMillan DC, McKernan M, McDonald AC, Stuart RC. Evaluation of an inflammation-based prognostic score in patients with inoperable gastro-oesophageal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:637–641. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Horie T, Kubota K. Inflammation-based prognostic score is a novel predictor of postoperative outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246:1047–1051. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181454171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crumley AB, Stuart RC, McKernan M, McDonald AC, McMillan DC. Comparison of an inflammation-based prognostic score (GPS) with performance status (ECOG-ps) in patients receiving palliative chemotherapy for gastroesophageal cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e325–e329. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roxburgh CS, Crozier JE, Maxwell F, Foulis AK, Brown J, McKee RF, Anderson JH, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Comparison of tumour-based (Petersen Index) and inflammation-based (Glasgow Prognostic Score) scoring systems in patients undergoing curative resection for colon cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:701–706. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinoshita A, Onoda H, Imai N, Iwaku A, Oishi M, Fushiya N, Koike K, Nishino H, Tajiri H. Comparison of the prognostic value of inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:988–993. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roxburgh CS, McMillan DC. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6:149–163. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao Y, Huang D. The value of the systematic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score in patients with gastric cancer: A literature review. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014;10:799–804. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.146054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer, corp-author. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma. 1st English. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co, Ltd; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreyev HJ, Norman AR, Oates J, Cunningham D. Why do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for gastrointestinal malignancies? Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:503–509. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(97)10090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436–444. doi: 10.1038/nature07205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang JE, Kim HN, Kim DE, Choi HJ, Jung SH, Shim HJ, Bae WK, Hwang EC, Cho SH, Chung IJ. Prognostic significance of a systemic inflammatory response in patients receiving first-line palliative chemotherapy for recurred or metastatic gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:489. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Clos TW. Function of C-reactive protein. Ann Med. 2000;32:274–278. doi: 10.3109/07853890009011772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Clos TW, Mold C. C-reactive protein: An activator of innate immunity and a modulator of adaptive immunity. Immunol Res. 2004;30:261–277. doi: 10.1385/IR:30:3:261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slaviero KA, Clarke SJ, Rivory LP. Inflammatory response: An unrecognised source of variability in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cancer chemotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:224–232. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(03)01034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McMillan DC, Elahi MM, Sattar N, Angerson WJ, Johnstone J, McArdle CS. Measurement of the systemic inflammatory response predicts cancer-specific and non-cancer survival in patients with cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2001;41:64–69. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2001.9680613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Imaoka H, Mizuno N, Hara K, Hijioka S, Tajika M, Tanaka T, Ishihara M, Yogi T, Tsutsumi H, Fujiyoshi T, et al. Evaluation of modified glasgow prognostic score for pancreatic cancer: A retrospective cohort study. Pancreas. 2016;45:211–217. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lien YC, Hsieh CC, Wu YC, Hsu HS, Hsu WH, Wang LS, Huang MH, Huang BS. Preoperative serum albumin level is a prognostic indicator for adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Lim T, Uhm JE, Park KW, Park SH, Lee SC, Park JO, Park YS, Lim HY, Sohn TS, et al. Prognostic model to predict survival following first-line chemotherapy in patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:886–891. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, Haile RW, Ahnen D, Bresalier R, McKeown-Eyssen G, Summers RW, Rothstein R, Burke CA, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:891–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothwell PM, Fowkes FG, Belch JF, Ogawa H, Warlow CP, Meade TW. Effect of daily aspirin on long-term risk of death due to cancer: Analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62110-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]