Abstract

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress is believed to play an important role in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease (AD). The accumulation of misfolded proteins and perturbation of intracellular calcium homeostasis are thought to underlie the induction of ER stress, resulting in neuronal dysfunction and cell death. Several reports have shown an increased ER stress response in amyloid precursor protein (APP) and presenilin1 (PS1) double-transgenic (Tg) AD mouse models. However, whether the ER stress observed in these mouse models is actually caused by AD pathology remains unclear. APP and PS1 contain one and nine transmembrane domains, respectively, for which it has been postulated that overexpressed membrane proteins can become wedged in a misfolded configuration in ER membranes, thereby inducing nonspecific ER stress. Here, we used an App-knockin (KI) AD mouse model that accumulates amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide without overexpressing APP to investigate whether the ER stress response is heightened because of Aβ pathology. Thorough examinations indicated that no ER stress responses arose in App-KI or single APP-Tg mice. These results suggest that PS1 overexpression or mutation induced a nonspecific ER stress response that was independent of Aβ pathology in the double-Tg mice. Moreover, we observed no ER stress in a mouse model of tauopathy (P301S-Tau-Tg mice) at various ages, suggesting that ER stress is also not essential in tau pathology–induced neurodegeneration. We conclude that the role of ER stress in AD pathogenesis needs to be carefully addressed in future studies.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, amyloid precursor protein (APP), amyloid-β (Aβ), endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER stress), presenilin

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD)4 is the most common neurodegenerative disease and the main cause of dementia. The neuropathological hallmarks of AD include extracellular deposits of amyloid-β (Aβ) as the major component of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (1). Aβ is generated from amyloid precursor protein (APP), a type I membrane protein, through sequential proteolytic cleavages mediated by the β- and γ-secretases. γ-Secretase is a membrane-associated complex consisting of four different proteins: presenilin1/2 (PS1/2), nicastrin (NCSTN), anterior pharynx–defective 1 (APH1), and presenilin enhancer 2 (PEN2). PS1/2 is a catalytic subunit (1).

For around two decades, APP- and/or PS1-overexpressing transgenic (Tg) mice have been used widely as AD mouse models for basic and clinical studies. However, the underlying processes of Aβ overproduction in conventional mouse models differ greatly from that in AD patients. APP overexpression in animal models overproduces in an unphysiological manner fragments other than Aβ such as soluble amyloid precursor protein, C-terminal fragment of APP, and APP intracellular domain. Moreover, APP and/or PS1 overexpression can induce an artificial endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response due to increased cytoplasmic calcium concentrations (2). To overcome these drawbacks of the overexpression paradigm, we recently developed mouse models utilizing an App-knockin (KI) strategy. The App-KI mice, which express humanized Aβ with familial AD mutations at endogenous levels, exhibit AD-associated pathologies, including pronounced Aβ amyloidosis and gliosis (3, 4). In contrast, App-KI failed to reproduce some of the observations made using conventional mouse models (3–5). For example, the early lethality of calpastatin-knockout (KO) × APP23 mice, which contradicted the chronic nature of AD, was not reproduced in calpastatin-KO × App-KI (3, 6). Moreover, with App-KI mice, we detected no calpain-dependent conversion of p35 to p25, which up-regulates cyclin-dependent enzyme 5 (CDK5) activity. Although calpain activation is generally considered to play an important role in AD progression due to its involvement in caspase-dependent neuronal cell death and CDK5-mediated hyperphosphorylation of tau, our observations indicate that the role of calpain may have been overestimated.

In this study, we focused our attention on ER stress. The accumulation of unfolded/misfolded proteins within the ER lumen along with the disruption of calcium homeostasis leads to ER dysfunction, known as ER stress. Under ER stress conditions, cells escape from serious damage by activating adaptive response pathways known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). UPR restores proteostasis in the ER by arresting protein synthesis, degrading unfolded/misfolded proteins, and increasing molecular chaperone concentrations. Conversely, UPR induces cell death signaling upon prolonged stress or serious damage. Several reports have suggested that ER stress induced by Aβ accumulation is involved in neurodegeneration in AD (7–9). To this end, exposure of hippocampal brain slices, primary neurons, or cell lines to oligomerized or fibrilized Aβ has been shown to induce ER stress (10, 11). Moreover, UPR up-regulation has been detected in several AD mouse models such as APP/PS1, 5XFAD, and 3XTg-AD (10–12). However, until the present time, it has been difficult to clarify whether ER stress is triggered by Aβ pathology in vivo. To answer this important question, i.e. which abnormally overexpressed membrane proteins or Aβ deposition triggers ER stress, we evaluated the ER stress response in several AD mouse models, including App-KI.

Results

UPR regulates three key pathways via three ER-binding proteins (13): pancreatic ER kinase (PERK), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1). The first pathway, triggered by PERK phosphorylation, arrests protein synthesis via abrogating the activity of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) by phosphorylation and activates ATF4–mediated gene expression of ER chaperones. The second pathway, initiated by ATF6, induces the expression of ER molecular chaperones such as GRP78/BiP and GRP94 and protein-folding enzymes such as protein-disulfide isomerases (PDIs) to prevent protein misfolding. In the third pathway, phosphorylated IRE1 induces the expression of genes related to protein folding, autophagy, and apoptosis (such as C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP)) by activating the transcription factor XBP1. Under normal conditions, PERK, ATF6, and IRE1 remain in an inactive state due to GRP78 binding. In response to ER stress, however, misfolded proteins interrupt GRP78 and sensor protein interactions, thereby initiating UPR signaling.

Several reports have described activation of the ER stress response in AD mouse models. For instance, in the 5XFAD model, which overexpresses familial AD-linked APP and PS1 mutants, phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) and XBP1 mRNA levels are elevated (14, 15). The APP/PS1 mouse shows age-dependent increases of GRP78, p-PERK, p-eIF2α, and CHOP (12). Moreover, increased GRP78 is also detected in the 3XTg-AD mouse, which expresses mutant APP, PS1, and tau (16). However, in contrast to these findings, Lee et al. (17) observed no UPR signals in Tg2576 mice. Accordingly, it remains controversial whether Aβ pathology is an essential trigger of ER stress.

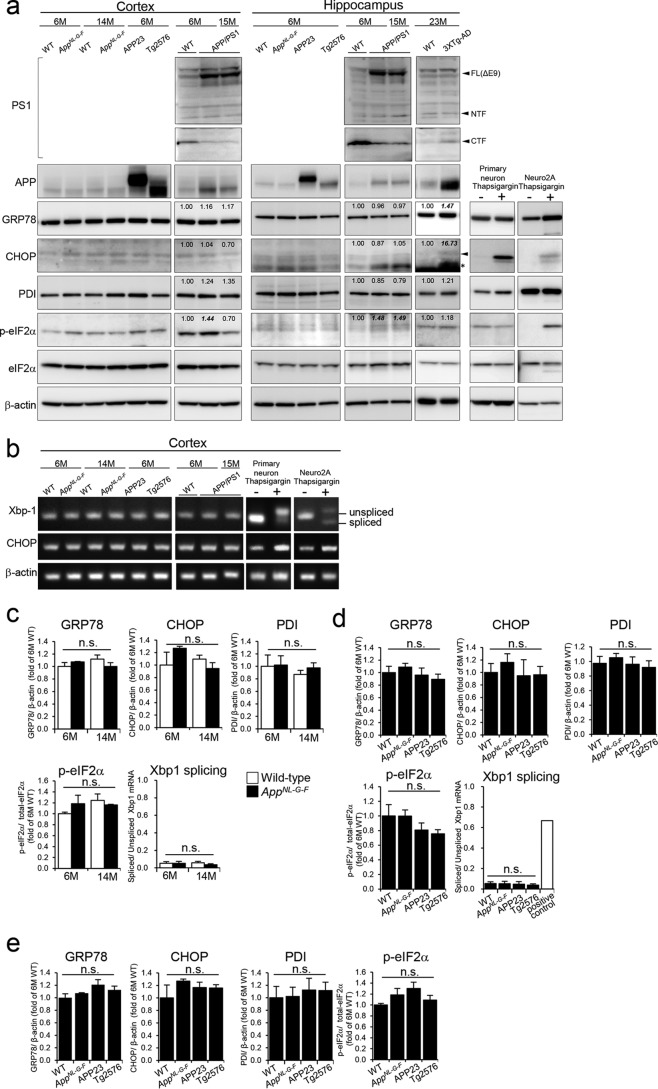

GRP78 acts as an important sensor of ER stress, and its expression is up-regulated by UPR to prevent protein misfolding. GRP78 also appears to be the most sensitive and earliest ER stress marker in APP/PS1-Tg mice (13). Based on this evidence, we first analyzed GRP78 as an ER stress marker. We also examined levels of several ER stress markers: CHOP, PDI, p-eIF2α, and spliced XBP1. To examine whether Aβ deposition induces ER stress, we quantified levels of ER stress markers in the cortices of young and older AppNL-G-F mice (Fig. 1, a, b, and c). In AppNL-G-F mice, Aβ accumulation begins at 2 months and occupies the entire cortex and hippocampus by around 9 months (3). Western blot analysis showed no significant up-regulation in any of the ER stress markers tested at 6 and 14 months in AppNL-G-F mice compared with wildtype (WT), suggesting that increased Aβ deposition is not correlated with the ER stress response (Fig. 1, a and c). Given that we detected elevation of ER stress markers except for PDI in thapsigargin-treated primary cultured cortical neuronal or Neuro2A cells (Fig. 1, a and b), our observations are not due to failure to specifically detect ER stress markers. PDI was increased in primary cortical neuronal cells even under more severe conditions (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Expression of ER stress markers in AppNL-G-F and APP-Tg mice. a, representative Western blot shows expression levels of ER stress markers in the cortices and hippocampi of 6- and 14-month (M)-old WT, AppNL-G-F, APP23, and Tg2576 mice. The expressions in 6- and 15-month-old APP/PS1 and 23-month-old 3XTg-AD mice were also determined. Values shown in figures are band intensity of each band, which is divided by intensity of β-actin (for GRP78, CHOP, and PDI) or total eIF2α (for p-eIF2α). As a positive control, ER stress markers in thapsigargin-treated primary cultured cortical neuronal cells or Neuro2a cells were confirmed. Arrowheads shows bands of CHOP and PS1, and the asterisk shows nonspecific bands. FL, full length; CTF, C-terminal fragment; NTF, N-terminal fragment. b, mRNA levels of unspliced/spliced XBP1 and CHOP were determined. XBP1 mRNA was detected by semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR. Unspliced/spliced XBP1 was observed as a 152/126-bp band, respectively. c–e, expression levels of ER stress markers in cortices (c and d) and hippocampi (e) were normalized to that of β-actin (for GRP78, CHOP, and PDI) or total level of eIF2α (for p-eIF2α) and reported as relative levels compared with expression in 6-month-old WT mice. The expression level of spliced XBP1 mRNA was divided by that of unspliced XBP1 mRNA. The positive control is thapsigargin-treated primary cultured cells. Data are shown as means ± S.E. (n = 3). Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance with one-way ANOVA. n.s., no significant difference. Error bars represent S.E.

To compare ER stress response between AppNL-G-F and APP-Tg mice, we analyzed ER stress markers using cortical and hippocampal samples (Fig. 1, a, b, d, and e). As APP is a membrane-binding protein, we expected that APP overexpression would induce chronic ER stress. However, we observed no significant increase of ER stress markers in two APP-overexpressing mouse models: APP23 and Tg2576 (Fig. 1, d and e). These results indicate that neither Aβ deposition nor APP overexpression induces detectable ER stress. As such, our observations contradict previous reports describing the ER stress induced in double-transgenic mice overexpressing mutant APP and PS1 (10–12). Consistent with previous reports, we detected activation of ER stress in APP/PS1 and 3XTg-AD mice. In contrast to AppNL-G-F and single APP-Tg mice, APP/PS1 mice showed an increased ER stress marker, p-eIF2α, in hippocampus (6 and 15 months) and cortex (6 months), and 3XTg-AD showed higher levels of GRP78 and CHOP in hippocampus compared with age-matched wildtype controls (Fig. 1a). These results indicate that this effect could be a nonspecific artifact caused by the genetic modification of PS1 or double modifications of APP and PS1. We confirmed overexpression of PS1(ΔE9) in APP/PS1 mice using antibodies and protocols that had been fully validated (18, 19). We must, however, indicate that we did not detect other ER stress markers in the APP/PS1 mouse brains in a manner distinct from the previous report (12), presumably due to the reasons described under “Discussion.”

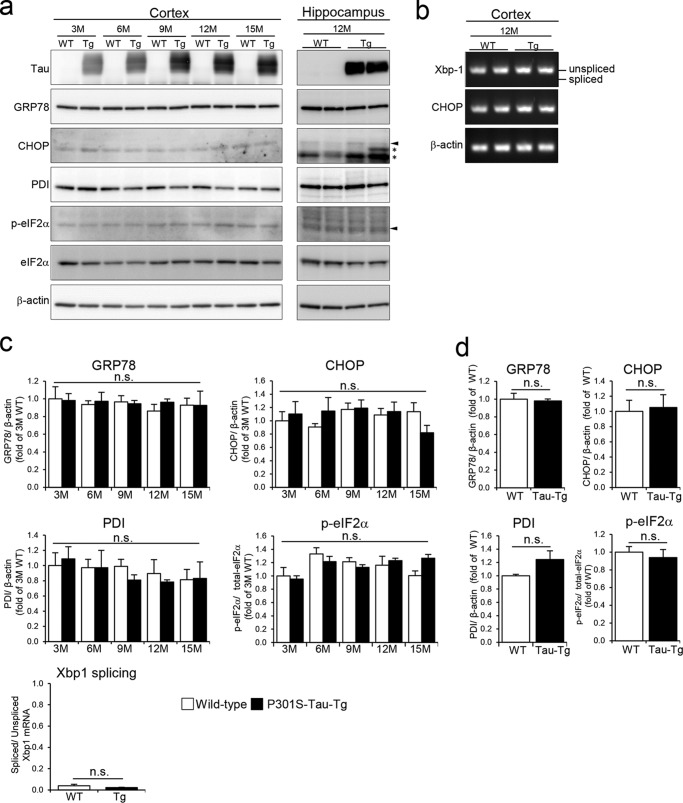

Under prolonged ER stress conditions, cells cease to protect themselves and turn on cell death signals. In AD and other neurodegenerative diseases, tau pathology correlates well with neurodegeneration (20). We therefore hypothesized that ER stress might mediate tau-induced neuronal cell death. To investigate this further, we analyzed ER stress markers in cortices (3–15 months) and hippocampi (12 months) of P301S-Tau-Tg mice on a C57BL/6 background (Fig. 2). In these mice, brain atrophy associated with neuronal cell death starts from around 9–12 months5; however, we observed no changes in all stress markers between 3 and 15 months (Fig. 2, a and b). These results suggest that tau pathology does not accompany ER stress and that the ER stress response is unrelated to tau-induced neurodegeneration.

Figure 2.

Expression of ER stress markers in P301S-Tau-Tg mice. a, expression levels of ER stress markers in the cortices (3–15 months (M)) and hippocampi (12 months) of WT and P301S-Tau-Tg mice were determined. Arrowheads show bands of CHOP and p-eIF2α, and asterisks show nonspecific bands. b, XBP1 mRNA was detected by semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR. c and d, mean levels ±S.E. of relative expression of ER stress markers (n = 3). c, cortex; d, hippocampus. Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance via two-way ANOVA. n.s., no significant difference. Error bars represent S.E.

Discussion

In the present study, we found an absence of ER stress responses in App-KI and single APP-overexpressing mice. We thus conclude that neither Aβ nor APP overproduction triggers ER stress. Lee et al. (17) have consistently shown that ER stress does not occur in Tg2576 mice. The elevated UPR detected in several lines of APP and PS1 double-transgenic mice is thus likely to be a nonspecific artifact. As presenilins are polytopic membrane proteins containing nine transmembrane domains, we suggest that mutant PS1 overexpression specifically impacts ER membranes in which presenilins are enriched (21, 22).

A number of studies have reported that PS1 plays a role in the regulation of ER calcium homeostasis (for reviews, see Honarnejad et al. (23) and Zhang et al. (24). PS1 modulates not only the function of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, which transfers calcium from the cytosol to the lumen, but also of ER-associated calcium channels such as the inositol trisphosphate receptor and ryanodine receptor (25–29). In addition, familial AD (FAD)-linked mutations of PS1 alter its activity in calcium transfer (for reviews, see Honarnejad et al. (23) and Zhang et al. (24). Alteration of the ER cytosolic calcium concentration is a strong inducer of ER stress as seen in cells treated with the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin (Fig. 1) (30). Based on these findings, the genetic modification of PS1 is very likely to affect the ER stress response. Indeed, FAD-linked PS1 mutation results in the delayed activation of UPR in fibroblasts and primary cultured neurons of mutant PS1-KI mice (31, 32). Moreover, deletion or overexpression of PS1 in primary neurons also alters the ER stress response (33, 34). Taken together, the ER stress responses observed in APP/PS1 double mutant mice are not causally associated with AD etiology. Artificial ER stress responses induce artificial cellular responses and cell death. We therefore suggest that the results obtained with APP/PS1 double mutant mice should be further validated.

In this study, however, we did not detect marked activation of ER stress in APP/PS1 mice even though we utilized a strain identical to that used by Barbero-Camps et al. (12) and Jankowsky et al. (35). We presume that partial reproducibility was due to reduced expression levels of APP and PS1 in the APP/PS1 mice (Fig. 1a) after a number of passages.

In addition to the above, we detected no ER stress response in a mouse model of tauopathy, suggesting that ER stress does not contribute to tau-induced neurodegeneration. It is plausible that tau overexpression will not induce ER stress because tau is basically a cytosolic protein.

Several groups have reported that the ER stress response is up-regulated in post-mortem human AD brains (14, 36, 37). In contrast, Katayama et al. (31) showed a significant decrease of GRP78 in the brains of AD patients. The post-mortem degradation of mRNA and protein may be different between control and AD patients because neurons in AD brain had undergone degeneration, which would accompany destruction of lysosomes and mitochondria, before sampling. We thus need to be careful when we analyze and discuss mRNA and protein levels in post-mortem samples. In addition, because calcium concentrations and calcium-related responses might be altered by post-mortem conditions, ER stresses in post-mortem samples require careful interpretation. To this end, we have shown an unphysiological activation of the calcium-dependent protease calpain in post-mortem mouse brains (5).

Our observations raise serious concerns surrounding efforts to translate basic findings obtained using APP/PS1 gene–modified mice to clinical applications. If pharmacological candidates that improve the pathological and neurological parameters of the APP/PS1 gene–modified mice exert their effects via the modification of nonspecific ER stress, then these candidates may not be effective in a preclinical setting or in clinically defined AD patients. Choosing appropriate models is thus extremely important if the mechanisms underlying AD are to be fully elucidated (4).

Experimental procedures

Animals

All animal experiments were carried out in accordance with RIKEN Brain Science Institute guidelines. We previously produced AppNL-G-F/NL-G-F-knockin (AppNL-G-F) mice using genomic DNA containing introns 15–17 of mouse App with the humanized Aβ sequence into which KM670/671NL (Swedish), I716F (Iberian), or E693G (Arctic) mutations (3) had been introduced. APP23 mice (38), which overexpress Swedish mutation–containing APP751, were maintained on a C57BL/6J background. Tg2576 mice (39), which overexpress Swedish mutation–containing APP695, were maintained on a mixed B6-SJL background. APP/PS1 (APPswe/PSEN1dE9) mice, which overexpress APP695 (Swedish) and PS1 (ΔE9), and 3XTg-AD mice, which are APP695 (Swedish)-transgenic/Tau (P301L)-transgenic/PS1 (M146V)-knockin, were maintained on a C57BL/6J background. P301S-Tau-Tg (Line PS19) mice were created on a B6C3H/F1 background (40). PS19 mice were back-crossed onto a C57BL/6 background.

Cell culture

Primary cultured cells were prepared as below. Cortices and hippocampi were separated from E16–18 embryos of WT mice and moved to Neurobasal medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Tissues were chopped with scalpels and treated with 5 ml of 0.25% trypsin at 37 °C for 15 min with rotation. Then 0.125 ml of 1% DNase I was added and mixed by pipetting. After centrifugation of the tissues at 1500 rpm for 3 min, 5 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution containing 0.125 ml of 1% DNase I was added to the pellet and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min while moving slightly in a water bath. Tissues were again centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 3 min, and the resulting pellets were suspended in 15 ml of Neurobasal medium containing 2% B27 and 0.5 mm glutamate. Cells were filtrated using a Falcon 2360 Cell Strainer (100-μm nylon) and seeded in cell culture plates with Neurobasal medium containing B27 and glutamate. Prepared cells at DIV7 were used for experiments. Neuro2A cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. To induce ER stress, cells were treated with thapsigargin (final 2 μm for 8 h for primary cells; final 5 μm for 18 h for Neuro2A cells).

Western blotting

Extirpated brains were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. The cortices were homogenized in 400 μl of Tris-HCl buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100) containing a protease inhibitor mixture and a phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich). The homogenates were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. Resulting supernatants were used for subsequent analyses. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce). An equivalent amount of protein from each animal was mixed with 4× sample buffer with 2-mercaptoethanol, separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and transferred electrophoretically to a 0.22-μm PVDF membrane (Merck Millipore). The membrane was treated with the ECL Prime blocking agent (GE Healthcare) and incubated with each primary antibody (Table 1) diluted in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST), pH 7.5, overnight at 4 °C. The membrane was washed three times in TBST for 5 min and treated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or -mouse IgG (GE Healthcare) for 1 h. Immunoreactive bands on the membrane were visualized with ECL Select (GE Healthcare) and scanned with a LAS-3000mini LuminoImage analyzer (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). The Neuro2A lysates were analyzed in a similar manner at an identical protein concentration.

Table 1.

Antibodies used for Western blot analyses

The following antibodies were used at the indicated dilutions to detect ER stress markers.

| Protein | Antibody | Dilution |

|---|---|---|

| APP | Merck Millipore catalog no. MAB348 (clone 22c11) | 1:2500 |

| Tau | Thermo Fisher catalog no. AHB0042 (Tau5) | 1:2500 |

| GRP78 | Abcam catalog no. ab21685 | 1:5000 |

| CHOP | Abcam catalog no. ab11419 | 1:2500 |

| p-eIF2α | Cell Signaling Technology catalog no. 3398 | 1:1000 |

| eIF2α | Cell Signaling Technology catalog no. 9722 | 1:1000 |

| PDI | Hiroi et al. (41) | 1:5000 |

| PS1 | Tomita et al. (18) | 1:5000 |

| Sato et al. (19) | 1:5000 | |

| β-Actin | Sigma catalog no. A5441 | 1:5000 |

RNA isolation and polymerase chain reactions (PCRs)

The cortex samples were homogenized in 1 ml of RNAiso Plus total RNA extraction reagent (Takara). Neuro2A cells and primary cultured cortical neuronal cells (1 × 107 cells/sample) were dissolved in 500 μm RNAiso Plus. Total RNA from each sample was isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions. To obtain complementary DNA, a reaction mixture containing 2 μg of RNA and Primescript reverse transcriptase (Takara) was incubated according to the manufacturer's directions for 60 min at 42 °C and then 10 min at 70 °C to stop the reaction. Semiquantitative PCR was performed using KOD FX Neo (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) for XBP1 or Ex-Taq (Takara) for CHOP and β-actin. PCR was conducted at 94 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 1 min using primers 5′-acacgcttgggaatggacac-3′ (sense) and 5′ccatgggaagatgttctggg-3′ (antisense) for XBP1; 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min using primers 5′-agaggagccagggccaacagaggtcacacg-3′ (sense) and 5′-tccggagagacagacaggaggtgatgccca-3′ (antisense) for CHOP; and 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min using primers 5′-gggtcagaaggattcctatg-3′ (sense) and 5′-ggtctcaaacatgatctggg-3′ (antisense) for β-actin.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as means ± S.E. Differences between groups were examined for statistical significance with one-way or two-way ANOVA.

Author contributions

S. H., A. I., N. K., N. W., T. O., M. Y., and T. S. planned and performed experiments and analyzed the results. S. H. and T. C. S. wrote the paper. T. C. S. organized the entire research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yukio Matsuba and Naomi Mihira (RIKEN Brain Science Institute) for technical assistance. We are grateful to Karen Hsiao-Ashe (University of Minnesota) for providing Tg2576 mice, Virginia M.-Y. Lee (University of Pennsylvania) for providing P301S-Tau-Tg mice, Taisuke Tomita (University of Tokyo) for providing PS1 antibody), and Susumu Imaoka (Kwansei Gakuin University) for providing PDI antibody.

This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for young scientists (B) (a Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) grant) (to S. H.), research grants from the RIKEN Special Postdoctoral Research Program (to S. H.), a grant-in-aid for scientific research (B) (a MEXT grant) (to T. S.), Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies (Brain/MINDS) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (to T. C. S.), and a research grant from RIKEN Brain Science Institute. S. H., T. S., and T. C. S. serve as a member, advisor and chief executive officer, respectively, for RIKEN BIO Co. Ltd., which sublicenses animal models to for-profit organizations, the profits from which are used for the identification of disease biomarkers.

T. Saito and T. C. Saido, unpublished data.

- AD

- Alzheimer's disease

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- PS

- presenilin

- Tg

- transgenic

- KI

- knockin

- Aβ

- amyloid-β

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- PERK

- pancreatic ER kinase

- ATF

- activating transcription factor

- IRE1

- inositol-requiring enzyme 1

- PDI

- protein-disulfide isomerase

- CHOP

- C/EBP (CCAAT/enhancer–binding protein)-homologous protein

- p-eIF2α

- phosphorylated eIF2α

- FAD

- familial AD

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. Hardy J., and Selkoe D. J. (2002) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356 10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chaudhari N., Talwar P., Parimisetty A., Lefebvre d'Hellencourt C., and Ravanan P. (2014) A molecular web: endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8, 213 10.3389/fncel.2014.00213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Saito T., Matsuba Y., Mihira N., Takano J., Nilsson P., Itohara S., Iwata N., and Saido T. C. (2014) Single App knock-in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 661–663 10.1038/nn.3697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sasaguri H., Nilsson P., Hashimoto S., Nagata K., Saito T., De Strooper B., Hardy J., Vassar R., Winblad B., and Saido T. C. (2017) APP mouse models for Alzheimer's disease preclinical studies. EMBO J. 36, 2473–2487 10.15252/embj.201797397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saito T., Matsuba Y., Yamazaki N., Hashimoto S., and Saido T. C. (2016) Calpain activation in Alzheimer's model mice is an artifact of APP and presenilin overexpression. J. Neurosci. 36, 9933–9936 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1907-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Higuchi M., Iwata N., Matsuba Y., Takano J., Suemoto T., Maeda J., Ji B., Ono M., Staufenbiel M., Suhara T., and Saido T. C. (2012) Mechanistic involvement of the calpain-calpastatin system in Alzheimer neuropathology. FASEB J. 26, 1204–1217 10.1096/fj.11-187740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hitomi J., Katayama T., Eguchi Y., Kudo T., Taniguchi M., Koyama Y., Manabe T., Yamagishi S., Bando Y., Imaizumi K., Tsujimoto Y., and Tohyama M. (2004) Involvement of caspase-4 in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and Aβ-induced cell death. J. Cell Biol. 165, 347–356 10.1083/jcb.200310015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kang E. B., Kwon I. S., Koo J. H., Kim E. J., Kim C. H., Lee J., Yang C. H., Lee Y. I., Cho I. H., and Cho J. Y. (2013) Treadmill exercise represses neuronal cell death and inflammation during Aβ-induced ER stress by regulating unfolded protein response in aged presenilin 2 mutant mice. Apoptosis 18, 1332–1347 10.1007/s10495-013-0884-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costa R. O., Ferreiro E., Oliveira C. R., and Pereira C. M. (2013) Inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase potentiates Aβ-induced ER stress and cell death in cortical neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 52, 1–8 10.1016/j.mcn.2012.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cornejo V. H., and Hetz C. (2013) The unfolded protein response in Alzheimer's disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 35, 277–292 10.1007/s00281-013-0373-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Endres K., and Reinhardt S. (2013) ER-stress in Alzheimer's disease: turning the scale? Am. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2, 247–265 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barbero-Camps E., Fernández A., Baulies A., Martinez L., Fernández-Checa J. C., and Colell A. (2014) Endoplasmic reticulum stress mediates amyloid β neurotoxicity via mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 2066–2081 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.03.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ron D., and Walter P. (2007) Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529 10.1038/nrm2199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Connor T., Sadleir K. R., Maus E., Velliquette R. A., Zhao J., Cole S. L., Eimer W. A., Hitt B., Bembinster L. A., Lammich S., Lichtenthaler S. F., Hébert S. S., De Strooper B., Haass C., Bennett D. A., et al. (2008) Phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α increases BACE1 levels and promotes amyloidogenesis. Neuron 60, 988–1009 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reinhardt S., Schuck F., Grösgen S., Riemenschneider M., Hartmann T., Postina R., Grimm M., and Endres K. (2014) Unfolded protein response signaling by transcription factor XBP-1 regulates ADAM10 and is affected in Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 28, 978–997 10.1096/fj.13-234864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Soejima N., Ohyagi Y., Nakamura N., Himeno E., Iinuma K. M., Sakae N., Yamasaki R., Tabira T., Murakami K., Irie K., Kinoshita N., LaFerla F. M., Kiyohara Y., Iwaki T., and Kira J. (2013) Intracellular accumulation of toxic turn amyloid-β is associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress in Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 10, 11–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee J. H., Won S. M., Suh J., Son S. J., Moon G. J., Park U. J., and Gwag B. J. (2010) Induction of the unfolded protein response and cell death pathway in Alzheimer's disease, but not in aged Tg2576 mice. Exp. Mol. Med. 42, 386–394 10.3858/emm.2010.42.5.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tomita T., Takikawa R., Koyama A., Morohashi Y., Takasugi N., Saido T. C., Maruyama K., and Iwatsubo T. (1999) C terminus of presenilin is required for overproduction of amyloidogenic Aβ42 through stabilization and endoproteolysis of presenilin. J. Neurosci. 19, 10627–10634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sato C., Takagi S., Tomita T., and Iwatsubo T. (2008) The C-terminal PAL motif and transmembrane domain 9 of presenilin 1 are involved in the formation of the catalytic pore of the γ-secretase. J. Neurosci. 28, 6264–6271 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1163-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ballatore C., Lee V. M., and Trojanowski J. Q. (2007) Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and related disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 663–672 10.1038/nrn2194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Annaert W. G., Levesque L., Craessaerts K., Dierinck I., Snellings G., Westaway D., George-Hyslop P. S., Cordell B., Fraser P., and De Strooper B. (1999) Presenilin 1 controls γ-secretase processing of amyloid precursor protein in pre-Golgi compartments of hippocampal neurons. J. Cell Biol. 147, 277–294 10.1083/jcb.147.2.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Area-Gomez E., de Groof A. J., Boldogh I., Bird T. D., Gibson G. E., Koehler C. M., Yu W. H., Duff K. E., Yaffe M. P., Pon L. A., and Schon E. A. (2009) Presenilins are enriched in endoplasmic reticulum membranes associated with mitochondria. Am. J. Pathol. 175, 1810–1816 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Honarnejad K., and Herms J. (2012) Presenilins: role in calcium homeostasis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44, 1983–1986 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang H., Sun S., Herreman A., De Strooper B., and Bezprozvanny I. (2010) Role of presenilins in neuronal calcium homeostasis. J. Neurosci. 30, 8566–8580 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1554-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Green K. N., Demuro A., Akbari Y., Hitt B. D., Smith I. F., Parker I., and LaFerla F. M. (2008) SERCA pump activity is physiologically regulated by presenilin and regulates amyloid β production. J. Cell Biol. 181, 1107–1116 10.1083/jcb.200706171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guo Q., Furukawa K., Sopher B. L., Pham D. G., Xie J., Robinson N., Martin G. M., and Mattson M. P. (1996) Alzheimer's PS-1 mutation perturbs calcium homeostasis and sensitizes PC12 cells to death induced by amyloid β-peptide. Neuroreport 8, 379–383 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stutzmann G. E., Caccamo A., LaFerla F. M., and Parker I. (2004) Dysregulated IP3 signaling in cortical neurons of knock-in mice expressing an Alzheimer's-linked mutation in presenilin1 results in exaggerated Ca2+ signals and altered membrane excitability. J. Neurosci. 24, 508–513 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4386-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chan S. L., Mayne M., Holden C. P., Geiger J. D., and Mattson M. P. (2000) Presenilin-1 mutations increase levels of ryanodine receptors and calcium release in PC12 cells and cortical neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 18195–18200 10.1074/jbc.M000040200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stutzmann G. E., Smith I., Caccamo A., Oddo S., Laferla F. M., and Parker I. (2006) Enhanced ryanodine receptor recruitment contributes to Ca2+ disruptions in young, adult, and aged Alzheimer's disease mice. J. Neurosci. 26, 5180–5189 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0739-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rogers T. B., Inesi G., Wade R., and Lederer W. J. (1995) Use of thapsigargin to study Ca2+ homeostasis in cardiac cells. Biosci. Rep. 15, 341–349 10.1007/BF01788366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Katayama T., Imaizumi K., Sato N., Miyoshi K., Kudo T., Hitomi J., Morihara T., Yoneda T., Gomi F., Mori Y., Nakano Y., Takeda J., Tsuda T., Itoyama Y., Murayama O., et al. (1999) Presenilin-1 mutations downregulate the signalling pathway of the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 479–485 10.1038/70265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Katayama T., Imaizumi K., Honda A., Yoneda T., Kudo T., Takeda M., Mori K., Rozmahel R., Fraser P., George-Hyslop P. S., and Tohyama M. (2001) Disturbed activation of endoplasmic reticulum stress transducers by familial Alzheimer's disease-linked presenilin-1 mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43446–43454 10.1074/jbc.M104096200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sato N., Urano F., Yoon Leem J., Kim S. H., Li M., Donoviel D., Bernstein A., Lee A. S., Ron D., Veselits M. L., Sisodia S. S., and Thinakaran G. (2000) Upregulation of BiP and CHOP by the unfolded-protein response is independent of presenilin expression. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 863–870 10.1038/35046500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terro F., Czech C., Esclaire F., Elyaman W., Yardin C., Baclet M. C., Touchet N., Tremp G., Pradier L., and Hugon J. (2002) Neurons overexpressing mutant presenilin-1 are more sensitive to apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi stress. J. Neurosci. Res. 69, 530–539 10.1002/jnr.10312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jankowsky J. L., Fadale D. J., Anderson J., Xu G. M., Gonzales V., Jenkins N. A., Copeland N. G., Lee M. K., Younkin L. H., Wagner S. L., Younkin S. G., and Borchelt D. R. (2004) Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue β-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific γ secretase. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 159–170 10.1093/hmg/ddh019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nijholt D. A., de Graaf T. R., van Haastert E. S., Oliveira A. O., Berkers C. R., Zwart R., Ovaa H., Baas F., Hoozemans J. J., and Scheper W. (2011) Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates autophagy but not the proteasome in neuronal cells: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death Differ. 18, 1071–1081 10.1038/cdd.2010.176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chang R. C., Wong A. K., Ng H. K., and Hugon J. (2002) Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2α (eIF2α) is associated with neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroreport 13, 2429–2432 10.1097/00001756-200212200-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sturchler-Pierrat C., Abramowski D., Duke M., Wiederhold K. H., Mistl C., Rothacher S., Ledermann B., Bürki K., Frey P., Paganetti P. A., Waridel C., Calhoun M. E., Jucker M., Probst A., Staufenbiel M., et al. (1997) Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 13287–13292 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hsiao K., Chapman P., Nilsen S., Eckman C., Harigaya Y., Younkin S., Yang F., and Cole G. (1996) Correlative memory deficits, Aβ elevation, and amyloid plaques in transgenic mice. Science 274, 99–102 10.1126/science.274.5284.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yoshiyama Y., Higuchi M., Zhang B., Huang S. M., Iwata N., Saido T. C., Maeda J., Suhara T., Trojanowski J. Q., and Lee V. M. (2007) Synapse loss and microglial activation precede tangles in a P301S tauopathy mouse model. Neuron 53, 337–351 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hiroi T., Okada K., Imaoka S., Osada M., and Funae Y. (2006) Bisphenol A binds to protein disulfide isomerase and inhibits its enzymatic and hormone-binding activities. Endocrinology 147, 2773–2780 10.1210/en.2005-1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]