Abstract

Background

To systematically review the current literature investigating the association between oral health and acquired brain injury.

Methods

A structured search strategy was applied to PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and CENTRAL electronic databases until March 2017 by 2 independent reviewers. The preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis guidelines were used for systematic review.

Results

Even though the objective was to assess the association between oral health and acquired brain injury, eligible studies focused solely on different forms of stroke and stroke subtypes. Stroke prediction was associated with various factors such as number of teeth, periodontal conditions (even after controlling for confounding factors), clinical attachment loss, antibody levels to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Prevotella intermedia. The literature showed no consensus on the possible association between gingivitis and stroke. Patients with stroke generally had poorer oral hygiene practices and oral health. Dental prophylaxis and professional intervention reduced the incidence of stroke.

Conclusions

Overall, oral health and stroke were related. Periodontitis and tooth loss were independently associated with stroke. However, prevention and timely intervention may reduce the risk of stroke. Stroke was the main cerebral lesion studied in the literature, with almost no publications on other brain lesions.

Keywords: Brain injury, Oral hygiene, Cerebrovascular disorders, Periodontitis, Oro-dental condition

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is among the most prevalent causes of disability and death [1]. Stroke is one of the commonest ABI impairments, and the third leading cause of death in the United States [2]. Epidemiologists and researchers have consistently suggested an association between measures of oral health and various chronic systemic diseases, like patients with ABI [1, 3, 4], even dating back to 1989 [5]. Neurological conditions such as stroke lead to physical weakness, lack of coordination and cognitive problems, thereby making it difficult to maintain good oral hygiene [6]. These diseases, therefore, constitute a considerable challenge in routine oral care [7, 8, 9].

Oral health is defined as “a state of being free from mouth and facial pain, oral and throat cancer, oral infection and sores, periodontal (gum) disease, tooth decay, tooth loss, and other diseases and disorders that limit an individual's capacity in biting, chewing, smiling, speaking, and psychosocial wellbeing” [10]. Globally, untreated caries in permanent teeth is the most prevalent condition with 35% of the population affected. Intentional or eventual tooth loss is the end stage for dental and periodontal infections [11]. With poor oral health common in lower socioeconomic groups as well as incidences of cerebrovascular diseases (CVDs), it is necessary to assess any potential association between CVDs and oral health. In systemic diseases, periodontitis is the most common oral condition [3, 12, 13]. Patients with periodontal conditions have a stronger systemic inflammatory response than those without periodontal conditions, thus having a strong association with ischemic stroke [3, 12, 14]. This association has been explored in epidemiological studies including cross-sectional [15], case-control [14, 16, 17], and cohort studies [12, 13]; yet, it remains contested as all relevant confounders have so far not been duly considered [18, 19]. Most studies of systemic diseases and their association with oral conditions use periodontal measures like history of periodontitis, periodontal pocket depth, clinical attachment loss (CAL), various dental indices, and other parameters like tooth loss and number of remaining teeth. However, many potentially relevant social, behavioral, and microbiological measures have gone unnoticed or have not been studied [8, 9, 20].

The chronic nature of periodontitis (as well as some other oral diseases) implies that patients may already have these conditions before the onset of neurological disorder, such as stroke [1, 14, 17]. With poor oral hygiene habits in patients with cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs), oral health may be affected by the presence of already defined systemic disease [21]. Patients with ABI have also been noticed with severe spontaneous jaw muscle activity, which might have consequences on the maintenance of oral health [22]. Therefore, it is very important to carefully examine the cause-effect relation, irrespective of the correlation between systemic diseases and oro-dental conditions. Despite growing consensus that oral health is an essential component of critical care, oral health apparently remains poorer in patients with systemic disease than in healthy controls [7, 8].

Acknowledging the growing importance of oral health in patients with ABI, the aim was to systematically review the current literature on the association between oral health and ABI.

Material and Methods

This review followed the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [23], and also followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist [24] to systematize data filtering and collection.

Search Strategy

The PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and CENTRAL bibliographic databases were searched in early March 2017 for studies assessing the association between oral health and ABI. Therefore, all articles that investigated the association of oral health with brain injury or the association of CVDs with oral health were assessed. Specific search strategies were created by the regional hospital's librarian with expertise in systematic reviews, together with the authors. The search strategy was restricted to English language publications using the combined terms “brain-injury” OR “cerebrovascular disorders” AND “oral hygiene” OR “oral health” OR “mouth disease.” A text-based search was also included along with the MESH terms to ensure inclusion of recently published/accepted articles that have not yet been registered in the MESH database.

Selection Strategy

Studies assessing the association between oral health in patients with brain injury and CVDs were included. ABI was defined, for this study, as any pathology (traumatic, infectious, developmental, or others) affecting the brain leading to past or present hospitalization after birth. However, studies focusing mainly on oral health status such as tooth loss, periodontal status, caries, and oral health-related quality of life condition without evaluating association with ABIs were excluded from the study. Those systemic conditions that are not proper afflictions per se, but rather symptoms of other anomalies and neurodegenerative disorder diseases were also excluded (e.g., apraxia, Parkinson disease, and cerebral palsy).

An additional inclusion criterion was that the study should have a study population in the age range of 18 years and above. No exclusions were made based on the type of intervention provided. The remaining articles were imported into a reference management software (Zotero, Center for History and New Media, George Mason University, Maryland, VA, USA) [25], and the duplicates were removed. Publications without abstract and those which were widely out of the scope of the study were eliminated. The remaining studies were sorted on the basis of their titles, abstracts, and PMID/ISBN. Finally, those studies in which the abstract fulfilled all the inclusion criteria were selected for full-text reading. In cases where studies met the eligibility criteria but the information in the abstract was insufficient, full texts of such articles were also obtained. Further literature search was performed based on the bibliography of the selected articles. The quality of evidence of the resulting studies was assessed using a preformed template [26].

Data Extraction

Two independent researchers (R.S.P. and M.K.) conducted data extraction and validity assessment of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. Kappa statistics was used to calculate the agreement between the authors regarding the inclusion of the studies. Any discrepancy between the researchers on the inclusion/exclusion of a study was discussed until the consensus was reached. The relevant information in each included study was entered into a predesigned data extraction form (K.I.). Data extraction included information on the study design, patient sampling, study location, examiner profession, type of ABI, intervention, comparison, and the outcome data. A meta-analysis was not performed as the included studies were heterogeneous in terms of methodology and ways of reporting the results for such analysis. However, one recent meta-analysis was published specifically looking for association between one aspect of oral health (periodontitis) explicitly in patients with ischemic stroke [27]. The present study attempts to encompass all types of ABIs with various oral health aspects. Therefore, data are presented in a narrative manner.

Results

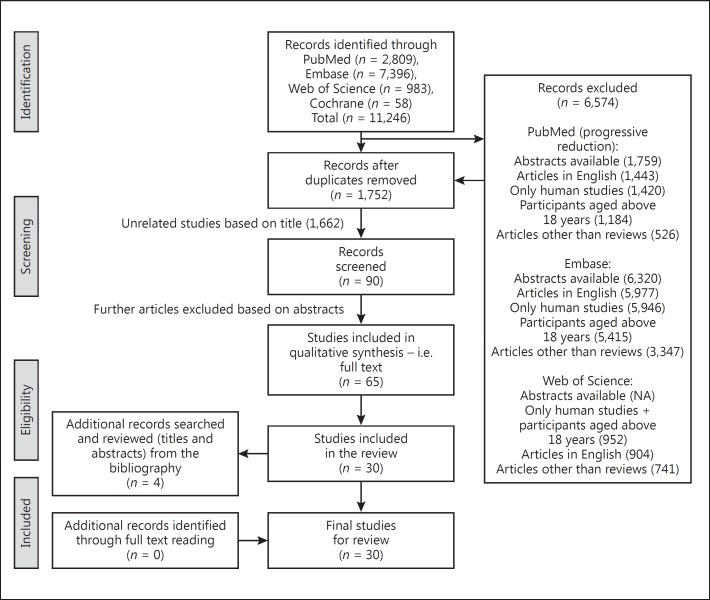

The search generated a total of 11,246 references from four databases: PubMed produced 2,809 papers, Embase produced 7,396 papers, Web of Science produced 983 papers and Cochrane produced 58 papers. PRISMA 2009 flow diagram [24] regarding the paper selection is shown in Figure 1. The full texts of 65 papers were obtained for further review. Two articles with similar authors had presented the same data in different journals with a similar objective, results, and conclusion [1, 14]. Therefore, only one [14] of the articles (higher impact journal/larger number of readers and citations) was included. On the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 30 studies were included in this systematic review. Bibliographical search of the selected studies revealed 4 more studies based on title and abstract. However, on full-text reading, none of these articles were eligible based on the inclusion criteria. Therefore, a total of 30 studies [3, 4, 5, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 21, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47] were reviewed in this paper (Table 1). The interrater agreement between the two reviewers was 0.865 (95% CI 0.737–0.992).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram regarding paper selection.

Table 1.

Methodological details and main outcomes for the included studies

| First author [Ref.], year | Tools used for oral assessment | Hypothesis-driven direction of relationship between stroke and oral health | Primary outcomes | Study summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lafon [28], 2014 | PI; GI and percentage of pockets >5 mm; DMFT index; bone loss | Stroke → oral health | Significant association between hypertension, CRP levels >5mg/L, BOP, bone loss, and ischemic stroke | Periodontal disease markers such as BOP and bone loss are independently associated with ischemic stroke |

| Kim [29], 2010 | PPD; oral hygiene; caries assessment; oral mucosa evaluation; frequency of tooth brushing; number of annual dental visits | Stroke → oral health | Stroke strongly associated with periodontitis (CAL ≥6 mm) Nonsignificant association between stroke and number of missing teeth, dental caries, and number of annual dental visits |

Periodontal inflammation is independently associated with hemorrhagic stroke |

| Grau [30], 1997 | Clinical teeth and periodontium evaluation; OPG; modified TDI index | Stroke → oral health | Patients had worse dental status, more severe periodontitis and periapical lesion than control subjects With social status and established vascular risk factors, poor dental status was independently associated with cerebrovascular ischemia | Recurrent or chronic bronchial infection and poor dental condition mainly resulting from chronic dental infection was associated with increased risk of cerebrovascular ischemia |

| Taguchi [31], 2013 | PPD; CAL; OPG | Oral health → stroke | Increased PD tended to be associated with the number of lacunar infarctions | Increased PD tended to be associated with an increased number of lacunar infarctions, as detected by MRI |

| Oluwagbemigun [4], 2015 | Self-reported measures (number of teeth) | Oral health → stroke | Participants with 23 or less teeth were at higher risk of stroke when compared to those with 28 teeth or more Stable increased risk between no teeth and 22 teeth followed by sharp significant decreased risk up to 32 teeth | Number of teeth has a nonlinear association with stroke, though this association should be further investigated |

| Jimenez [13], 2009 | PPD; alveolar bone loss; plaque (0–3); gingivitis (0–3) | Oral health → stroke | Compared to men with bone loss score ≤0.5 mm, men with bone loss score >1.5 had more than 3 times higher HR of cerebrovascular disease, among confirmed ischemic events (n = 27) | A significant association found between history of periodontitis as measured by alveolar bone loss and incidence of cerebrovascular disease, independent of established cardiovascular risk factors This association was stronger among younger men (<65 years) |

| Elter [32], 2003 | AL assessment (+3 mm) | Oral health → stroke | Weak independent association of AL with stroke/TIA Stroke/TIA was prevalent in 13.5% of periodontal examinees, 15.6% of dentate non examinees, and 22.5% of edentulous persons Highest quartile of AL and edentulism were associated with stroke/TIA |

The authors make no inference about causality from their results |

| Miyatani [33], 2015 | Number of remaining teeth; dental caries; dental restoration; frequency of tooth brushing; frozen saliva samples | Stroke → oral health |

cnm collagen-binding detected in 28.1% subjects and cerebral microbleeds detected in 30.9% Incidence of cerebral microbleeds significantly higher in carriers of S.mutans positive for the cnm protein The cerebral microbleed detection rate significantly higher in the cnm collagen binding activity |

cnm-positive S. mutans increases cerebral microbleeds, and is an independent risk for the development of cerebrovascular disorders |

| Slowik [34], 2010 | CAL; periodontal pocket | Stroke → oral health | Patients with advanced periodontitis or edentulism had greater neurological deficit on admission and worse outcome at hospital discharge measured with the mRS | Advanced periodontitis or edentulism in patients with ischemic stroke is associated with greater neurological deficit on admission |

| Nader [35], 2011 | CAL; GI | Stroke → oral health | Patients had higher loss of attachment than controls Gingivitis was not associated with risk of cerebral ischemia More severe periodontitis (CAL ≥6 mm) detected among men in patients with cerebral ischemia |

Periodontitis is an independent risk factor for cerebral ischemia, especially in men |

| You [36], 2009 | Subject reported tooth loss | Oral health → stroke | Participants with 17–32 missing teeth had higher CRP and higher WBC, no difference in albumin, and an OR of stroke of 1.28 compared to completely edentulous participants Those with 1–16 teeth lost did not differ in CRP and WBC, had higher albumin, and no increased stroke prevalence CRP or WBC did not attenuate associations between tooth loss and stroke |

Tooth loss positively associated with CRP, WBC, and stroke/TIA Inflammatory markers CRP and WBC did not confound associations between tooth loss and stroke |

| Pussinen [37], 2004 | Serum IgA and IgG antibodies to Aa and Pg by multiserotype ELISA | Oral health → stroke | No statistically significant difference between mean antibody level against Aa and Pg between stroke and nonstroke at baseline Significant difference between cases free of stroke at baseline IGA-seropositive for Aa than their controls (41.3 vs. 29.3%) Patients with history of stroke at baseline with higher IgG seropositive for Pg than their controls (79.7 vs. 70.2%) |

Elevated serum IgA-class antibody level to Aa predicted stroke Elevated IgA-antibody level to Pg predicted a recurrent stroke in subjects with a history of stroke at baseline |

| Ghizoni [38], 2012 | Pocket probing depth; CAL; BOP; PI; subgingival plaque sample for DNA extraction (PCR analysis) | Stroke → oral health | In test and control groups, respectively, 60 and 10% showed presence of Pg Aa DNA not detected in any groups by conventional or real-time PCR Greater prevalence of Pg in test group compared to control group Increased PPD and CAL in the ischemic group, while increased levels of Pg detected in hemorrhagic group Positive correlation between PPD and prevalence of Pg only in the ischemic patient group |

Stroke patients had deeper pockets, more severe AL, increased BOP, increased PI, and their pockets harbored increased levels of Pg Findings suggest periodontal disease is a risk factor for the development of cerebral hemorrhage or infarction |

| Grau [14], 2004 | CAL; GI; PI; DMFT | Stroke → oral health | Mean CAL was higher, indicating more severe periodontitis, in CVD patients than in both control groups After adjustment for age, sex, number of teeth, and other co-variables, increasing severity of periodontitis associated with increasing risk of cerebral ischemia Severe periodontitis increased the risk by a factor of 4.3 Periodontitis represented a risk factor in men and younger subjects but not in women or older individuals (>60 years) Severe radiological bone loss and severity of gingivitis were significantly associated with cerebral ischemia |

Periodontal disease significantly associated with cerebral ischemia Risk is higher for younger men (<60 years) |

| Lee [39], 2013 | ICD9-CM code 523.0–523.5 | Oral health → stroke | Stroke incidence rate increased as age increased Men had significantly higher stroke incidence than women Subjects with intensive treatment or tooth extraction had higher stroke IR Subjects without PD treatment had highest stroke incidence among all subjects After adjustment of age, sex, and comorbidity, the prophylaxis group and the intensive treatment group had significantly lower hazard ratio for stroke than non-PD group (HR, 0.78 and 0.95, respectively) For the PD without treatment group, the hazard ratio was significantly higher than the non-PD group (1.15) |

PD increases incidence of ischemic stroke, especially among the younger population |

| Söder [40], 2015 | PI: number teeth; CAI; GI | Oral health → stroke | GI and CAI were significantly higher in stroke group No significant differences between groups with or without stroke regarding age, education, income, dental plaque index score, or in number of missing teeth GI appeared to be principal independent predictor associated with 2.20 times the odds of stroke | The authors suggest a clear association of gingival inflammation with stroke |

| Sen [41], 2013 | Periodontal assessment: HPD defined as the highest textile of extent (% of sites) with attachment loss of >5 mm; IL-6; s-ICAM | Stroke → oral health | 38% showed PD and 26% had recurrent vascular events HPD patients had higher levels of IL-6 and s-ICAM HPD was associated with recurrent vascular events before (HR, 2.6) and after adjustment for significant confounders – age and stroke status (HR, 2.5); adjustment for possible confounders – age, male, years of education, and cardioembolic strokes (HR, 2.8); and adjustment for propensity score that accounted for all potential measured confounders (HR, 2.8) | There is an independent association between HPD and recurrent vascular events in stroke/TIA patients |

| Wu [12], 2000 | No periodontal disease; mild gingivitis; periodontitis | Oral health → stroke | Fatal and incident events highest for edentulous sample as compared to those with periodontitis, gingivitis or no disease When age taken into account, periodontitis and edentulism both higher in sample with CVE After adjustment of demographic variables and well-established risk factors for cardiovascular disease, periodontitis significantly associated with increased risk for total CVA and nonhemorrhagic stroke, but not for hemorrhagic stroke |

Study suggests that periodontitis is significantly associated with risk of developing CVA and, in particular, nonhemorrhagic stroke |

| Morrison [42], 1999 | Gingivitis; periodontitis; number of teeth | Oral health → stroke | RRs for fatal CHD and CVD associated with severe gingivitis higher than those for mild gingivitis, which was in turn higher for those without periodontal disease | Authors conclude that it is unclear to what extent the observed association reflects an underlying genetic predisposition to both periodontal disease and CVD, and to what extent it reflects a causal relationship |

| Joshipura [3], 2003 | Self-reported | Oral health → stroke | Men with ≤24 teeth at baseline at higher risk for stroke compared with those with ≥25 teeth (HR, 1.57), controlling for confounders All categories of tooth loss at elevated risk Having ≤24 teeth significantly associated with increased risk of stroke (HR, 1.50) Men with periodontal disease at baseline had moderately increased risk of ischemic stroke (HR, 1.33) Association between baseline number of teeth and ischemic stroke only slightly higher among people with periodontal disease compared with those without |

Periodontal disease showed a modest association with increased risk of ischemic stroke This association was higher among younger individuals |

| Loesche [21], 1998 | Number of teeth; denture usage; PPD; AL; gingival recessions; PI; gingivitis; PBI; brushing and flossing habits; salivary flow | Oral health → stroke | Stimulated salivary flow significantly reduced in dentate and edentulous subjects with CVA compared to subjects without Resting saliva higher in subjects with CVA Percentage of teeth with probing depths and attachment loss <4 mm, and 4–6 mm, did not differ between subjects with and without CVA. 21% of teeth in subjects with CVA had attachment loss >6 mm compared to 12% of teeth in subjects without Prevalence of visible plaque among CVA subjects significantly higher than subjects without CVA The subjects with CVA had significantly higher proportion of bleeding gingivitis 96% of non-CVA subjects reported brushing their teeth daily, which was significantly higher than the 84% prevalence reported by the CVA subjects |

The authors suggest that something as simple as annual teeth cleanings may be protective in an older, male population of US veterans Furthermore, since the design of their study was cross-sectional, they could not generalize the findings to other populations |

| Lee [15], 2006 | CAL and author developed ‘Periodontal Health Status’ Indices I & II | Oral health → stroke | PHS I (significantly) and PHS II associated with prevalence of stroke history Dentition status significantly associated with stroke history Completely edentulous and partially edentulous subjects had greater likelihood of stroke history compared to subjects with teeth in both arches Subjects with greater proportion (statistically nonsignificant) of sites with +2 mm CAL were 51% more likely to have history of stroke. PHS I significantly associated with stroke history PHS II not significantly related to stroke history With adjustment for age and tobacco alone, PHS I & II did not achieve statistical significance |

Some evidence of association is seen between periodontal disease and stroke in older adults It is unclear if periodontal disease, as measured by the PHS index, is an independent risk factor for stroke or simply a risk marker that reflects the detrimental effects of risk factors common to both periodontal disease and stroke |

| Syrjänen [5], 1989 | BOP; subgingival calculus, suppuration in the gingival pockets; subgingival calculus; TDI; OPG | Stroke → oral health | BOP common among patients than among controls in both males and females (p < 0.01). Severe dental infection and stroke had a significant association (p < 0.02) | An association between bacterial infection and ischemic cerebrovascular disease in patients under 50 years of age |

| Hosomi [43], 2012 | No oral examination | Stroke → oral health | Serum hs-CRP levels significantly associated with acute ischemic stroke Serum antibody level of Pi significantly higher in stroke patients than in patients with no stroke Anti-Pi antibody significantly associated with Bulb/ICA atherosclerosis after controlling associated factors |

Anti-Pg antibody may be associated with atrial fibrillation, and anti-Pi antibody may be associated with carotid artery atherosclerosis |

| Sim [16], 2008 | Periodontal probing; oral hygiene; dental caries; mucosal evaluation; CAL; oral health behaviors | Stroke → oral health | Stroke strongly associated with periodontitis After controlling for confounders, OR of periodontitis was 5.7 for ischemic stroke and 2.4 for hemorrhagic stroke | Periodontal inflammation is an independent risk factor for stroke Association between periodontitis and stroke was very strong among younger adults |

| Pradeep [17], 2010 | Periodontitis; PI; GI | Stroke → oral health | After adjusting for age and gender, severe periodontitis (periodontal pocket depth >4.5) significantly associated with cerebrovascular accidents | Data from the study supports the proposed link between periodontitis and CVDs |

| Diouf [44], 2015 | CA; pocket depth; plaque; PBI; CPITN | Stroke → oral health | Various periodontal parameters significantly associated with stroke; PI, CAL, PPD also associated with stroke | Periodontal disease is associated with stroke in the African and Senegalese population |

| Leira [45], 2016 | PD; CAL; gingival recession; plaque score; BOP; number of missing teeth | Stroke → oral health | Mild (p = 0.09), moderate (p = 0.09), and severe (p = 0.03) chronic periodontitis have positively strong association with LI. LI group had significantly (p < 0.0001) higher recession, CAL, PD, plaque scores, BOP and missing teeth The association remained after adjusting for confounding factors like hypertension, DM, smoking, alcohol and statins |

Oral health in patients suffering from LI is significantly poorer as compared to age gender-matched healthy controls even after controlling for confounding factors |

| Tonomura [47], 2016 | Oral saliva and dental plaque specimen for cnm-positive S. mutans | Oral health → stroke | Total number of CMBs significantly higher in subjects with cnm-positive S. mutans compared to those without (p = 0.002). The relative ratio for total CMBs with cnm-positive S. mutans compared to those without was 1.93 When number of total or deep CMBs was categorized into 0 (none), 1 or 2 (few), and ≥3 (multiple) groups, there were significant differences in the positive rate of cnm-positive S. mutans among the three groups: the group with multiple CMBs showed significantly greater rate of cnm-positive S. mutans cnm-positive S. mutans was associated with hypertensive ICH before and after adjustment for established risk factors for ICH, such as age, sex, mean blood pressure, and creatinine clearance |

cnm proteins of S. mutans may be associated with development of deep CMBs and ICH with a mechanistic link to chronic inflammation |

| Del Brutto [46], 2017 | Number of remaining teeth | Oral health → stroke | Of the 22 incident strokes, severe edentulism was noted in 14 (64%), whereas 215 had severe edentulism out of 785 participants without stroke (27%) with an odds ratio of 4.64 (p = 0.002) | Severe edentulism is a major factor independently predicting incident strokes |

Aa, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans; AL, attachment level; BOP, bleeding on probing, CAL, clinical attachment loss; CAI, calculus index; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, class interval; CM, clinical modification; CMB, cerebral microbleeds; CPITN, community periodontal index of treatment needs; CT, computed tomography; CRP, C-reactive protein; CVA, cerebrovascular accidents; CVE, cerebrovascular events; DM, diabetes mellitus; DMFT, decayed, missing, filled teeth; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; GI, gingival index; HPD, high periodontal disease; HR, hazard ratio; ICA, internal carotid artery; ICD, international classification of diseases; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IL, interleukin; LI, lacunar infarct; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale; OPG, orthopantomograph; OR, odds ratio; PBI, papillary bleeding index; Pi, Prevotella intermedia; PI, plaque index; Pg, Porphyromonas gingivalis; PCR, polymerized chain reaction; PHS, periodontal health status; PPD, periodontal pocket depth; RR, relative risk; S. mutans, Streptococcus mutans; SWI, susceptibility-weighted imaging; TDI, total dental index; TIA, transient ischemic attack; WBC, white blood cell.

Even though the objective of this review was to assess the association of oral health and ABI, all the final eligible studies included were conducted on individuals with different forms of stroke and its subtypes (ischemic, hemorrhagic, lacunar infarction, and CVAs), showing lacunae of almost no studies in other ABI diseases. The tools that were used for assessing the presence, degree, and severity of brain injury and CVDs were, majorly: International Classification of Diseases (ICDs), self-reported history, and radiographical imaging. Further, the oral health and oral hygiene assessment tools used were: CAL, gingival index, plaque index, bleeding on probing, decayed, missing, filled teeth (DMFT) indices, number of missing teeth, etc.

Apart from certain register-based studies, most of the studies were conducted in a hospital setting, with or without controls drawn from the general population. Seventeen studies were observational studies and 13 studies were case-control studies. The outcomes and summary of the reviewed studies are presented in Table 1. In addition, the direction of the association (oral health to stroke or stroke to oral health) of the included studies is also presented in Table 1. Out of the 30 included studies, 15 studies looked on the association with a hypothesis that oral health has an effect on stroke, and 15 studies looked at the effect that stroke has on oral health (Table 1).

Social and Behavioral Aspects

It was found that dental prophylaxis and periodontal treatment reduces the incidence of ischemic stroke [39]. Kim et al. [29] and Sim et al. [16] found that the patients who had a stroke brushed their teeth more frequently than their control population as a result of having guardian assistance. However, they noted that annual dental visits were not related to presence of stroke. Grau et al. [14] reported that patients with cerebral diseases have more than one annual dental visit and also toothbrushing frequency similar to the healthy controls. However, Loesche et al. [21] reported that patients with CVAs have poorer habits of brushing, flossing, and seeking professional dental cleaning and require help in brushing than those without stroke.

Clinical Aspects

Various studies evaluated the association (or role) of periodontal condition, number of teeth absent/present, microbiological, and biomarker factors with stroke.

Tooth Conditions

It has been reported that number of teeth may indicate a risk for stroke [3, 31, 44] with significantly higher number of affected patients presenting with a lower number of teeth as compared to healthy participants [4, 12, 21, 36, 38, 45] even after adjusting for age and gender [4, 45]. Grau et al. [14] conducted a study on stroke patients with separate controls drawn from population and hospital which shows patients had significantly lower number of teeth compared to the population controls. However, several studies have found no association between stroke and the number of teeth [13, 29, 33].

Lafon et al. [28] reported that DMFT >20, on adjusting for gender and age, with an odds ratio (OR) of 4.37 was a significant factor for stroke. However, Kim et al. [29], in a study of 165 stroke patients, found no significance of DMFT and stroke. Soder et al. [40] assessed dental calculus in 1,676 participants (39 stroke patients) and found significant differences between the patients with stroke and participants without stroke (p = 0.017). Grau et al. [30] found using the total dental index (TDI) that poor dental status was associated with cerebrovascular condition (OR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.04–4.6). However, Syrjanen et al. [5] reported that TDI was nonsignificant in 40 patients with cerebral infarction and their matched controls. Leira et al [45] found a significantly (p < 0.0001) higher number of missing teeth in patients with lacunar infarction than the controls. Del Brutto et al. [46] showed that high blood pressure and severe edentulism are independent risk factors increasing stroke incidence, after adjusting for confounding factors.

Gingivitis/Periodontitis

Gingivitis was not consistently reported as a factor associated with stroke. Certain studies [14, 38, 40, 45] report significantly poorer gingival conditions in affected patients, whereas other report no association [13, 35, 42].

Various studies report a strong association of periodontal conditions with stroke [12, 14, 17, 29, 38, 41, 45] even after controlling for confounders [16, 29, 42, 44]. The severity of periodontitis seems to be related to the brain damage condition as well [35]. Sim et al. [16] found that the association with periodontitis had a dose-response effect (i.e., as the severity of periodontitis increased from none/mild to severe, so did the OR of stroke). Syrjanen et al. [5] reported significant differences between cases and controls within genders with subgingival calculus and suppuration in gingival pockets significantly higher in cases than controls. TDI was nonsignificant. Slowik et al. [34] reported that patients with advanced periodontitis had a greater neurological deficit on admission and worse outcome on discharge. However, stroke severity, but not advanced periodontitis or edentulism, had a higher effect on the outcome of the stroke patients in their study. Another study found a modest association between baseline periodontal disease history and ischemic stroke [3].

CAL was also significantly poorer in stroke patients [14, 17, 38, 45]. Lee et al. [15], after adjusting for age and tobacco use, found that completely edentulous and partially edentulous elderly adults with appreciable CAL were significantly more likely to have a history of stroke compared to dentate adults without appreciable attachment loss [15]. Elter et al. [32] found that stroke was weakly associated with attachment loss. This association increased with every 3 mm increase in attachment loss, even after adjusting for other risk factors. Similar finding was seen in another study [14]. One study reported no significant difference in presence or absence of brain damage and CAL [31].

Microbiology and Biomarkers

Pussinen et al. [37] noted an elevated level of serum IgA-class antibody to Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) predicted stroke. An elevated level of IgA-antibody to Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) predicted a recurrent stroke in subjects with a history of stroke or coronary heart disease at baseline. They suggest that aggressive forms of periodontitis addressed to Aa, usually occurring at young age (<35 years of age), and Pg developing at adult age are associated with incidence of stroke. Also, Ghizoni et al. [38] showed that the patient group had an increased number of sites contaminated with Pg and greater prevalence of periodontal disease with a positive correlation between probing depth and levels of Pg in ischemic stroke. Hosomi et al. [43] found that serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels were significantly associated with acute ischemic stroke even after controlling for other factors. Serum antibody level for Prevotella intermedia was significantly higher in stroke patients than in patients with no previous history of stroke [43]. Tonomura et al. [47] found a significant association of cnm-positive Streptococcus mutans with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and cerebral microbleeds (CMB) along with a correlation between the collagen binding activity and number of deep CMBs, postulating a possible mechanistic link between S. mutans and CMB and ICH.

Discussion

The current systematic review aimed at evaluating the literature on the association between oral health and ABIs. The first apparent observation after the selection of the studies was that all the included studies were performed only on stroke population indicating a lacuna of virtually no studies in other ABIs. ABI, except stroke, has been neglected in this field for decades. In addition, all the included studies were either case-control or cohort; thereby, the resulting level of evidence of this review was at level 3 [48].

Several reviews have been conducted focusing specifically on the relationship between periodontitis and stroke [26, 49, 51, 52, 53, 53]. Unlike this review, the previously conducted systematic reviews (2003–2016) have been: (1) focused on only periodontitis, thereby not fully encompassing other oral factors such as the microbiological and behavioral aspects, (2) focusing only on stroke and not the various other brain injury conditions, and (3) with a combined cohort of stroke with other systemic diseases like cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis, thereby increasing the confounding factors, and causing bias. All reviews [27, 49, 50, 51, 53] except one [52] had similar results to our study, showing a moderate association of periodontitis to stroke. Khader et al. [52] in their meta-analysis found no strong evidence that periodontal infection increased the risk of stroke. All reviews agree, including this, that the potential limitations present within the included studies affect the drawing of a concrete conclusion that a causal relationship exists between oral health and stroke. Though it may seem that periodontitis is, at the very least, moderately associated and an independent risk factor for stroke, determining the causal nature between the two calls for more controlled interventional studies rather than the present observational and case control studies. The authors support the recommendation of Scannapieco et al. [53] that large-scale multicenter placebo-controlled RCTs need to be conducted to determine if periodontal-brain injury relation is “causal” or “casual” and if periodontal treatment effectively reduces mortality from CVDs as a primary outcome.

While studying the association of stroke with other systemic conditions, it is important to take into account the various adventitious factors that play a role in the causation or prevention of either disease. Age, gender, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, smoking, education, income, etc. are some of the common risk factors associated with stroke. The studies included in this review positively take into account the various confounding factors during analysis of their data [5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 24, 25, 26, 29, 31, 32, 35, 36, 37, 39, 41, 51]. This provides a clearer and stronger picture of the effect that periodontitis has on stroke and vice versa.

Conflicting reports were seen with tooth brushing and flossing habits. While some studies showed patients fare better in frequency of tooth brushing and flossing [16, 29], others showed that patients have poorer oral hygiene practices [28]. The level of guardian assistance in provision of oral hygiene interventions during the stay at the hospital/rehabilitation center plays a major role in determining the oral hygiene practices of the participants [57]. The level of importance placed on oral care by the rehabilitation unit's nursing and ward staff and/or by the patients’ family, has an effect on the resultant oral hygiene. It has been observed that oral care has been given a low priority by the caregivers [58, 59, 60, 61] with a belief that it does not provide significant benefits [62], along with a strong dislike among the staff with regard to providing oral care [61]. This is reinforced by inadequate training for the nursing staff [58] and use of unfocused care policies [60, 63].

Periodontitis is caused by local infections with periodontal pathogens, which in turn leads to systemic reactions, such as inflammation and immunological reactions [47]. With an increase in local infection in the periodontal pockets, a systemic inflammatory response is triggered leading to the release of inflammatory mediators like CRP [43]. This marker predicts the occurrence of cerebral infarction later in life. The total number of teeth lost may reflect the life-long inflammatory state of the patient. Therefore, those patients with a fewer number of teeth may have an increased risk of having a stroke or other systemic diseases [4]. However, if tooth loss is due to other factors like caries or trauma, and the loss is affected at the early stages of life, the patients might not have been affected by periodontal infection for the remaining period of their lives [5, 42]. In such conditions, an adverse effect of poor nutrition and altered dietary habits may be an indirect cause of stroke [55].

Syrjanen et al. [54] first suggested the possibility of association between chronic inflammation (including periodontitis) and stroke. Though several studies have been conducted since then to examine this relation, there are still conflicting reports in this regard. Many of the studies included in the present review, ranging from the year 1989 to 2016, showed that an association exists between periodontitis and stroke, and the risk is higher among younger men (<65 years) [3, 5, 13, 14, 16, 39]. However, some of the studies also showed that the apparent weak association found in their results (even after adjusting for confounding factors) could be due to residual confounding [55].

Various included studies reported an independent association of markers of periodontitis with stroke [16, 28, 29, 30, 35, 41]. Tooth loss, the end stage of periodontitis, was found to be a significant risk factor [36, 55]. Although there may be several reasons for tooth loss, e.g. trauma or intentional tooth extraction performed by the dentist, etc., oral diseases are the primary cause of tooth loss [56]. The sequelae to tooth loss begin with plaque and calculus accumulation, loss of attachment of the gingiva to the tooth leading to gingival recession, gradual loss of the periodontal ligament fibers which “loosen” the teeth from the socket and, ultimately, tooth loss. It is therefore of utmost importance to take preventive measures or to consider early intervention, especially in medically compromised patients.

Pg and Aa along with S. mutans [33] are the commonly studied microorganisms that have been implicated in periodontitis [37, 38]. This review found that patients affected by stroke had a higher prevalence and increased number of sites affected by the periodontal pathogens [33, 37, 38]. These microorganisms are invasive to the connective tissue and stimulate the synthesis of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators [64]. They have also been identified in atheromatous plaques of CVD patients [65, 66], thereby suggesting a possible role for Pg and Aa in the development of the lesion. A possible role of S. mutans inducing hemorrhagic changes in perforating arterioles, therefore leading to ICH and CMB has also been proposed [47].

The authors believe that the current literature review brings updated insight on top of the already published reviews in this field. Unlike previous literature reviews, which mainly focused on specific oral health variables (such as periodontitis), the current review encompassed a broad range of variables including social and behavioral aspects, all clinical and microbiological aspects, to have a “bird's eye” view of the potential association. Moreover, previous literature reviews mainly focused on stroke, whereas the current review's aim was to evaluate all the ABI conditions. In addition, multiple scientific databases were searched, thereby ensuring maximum coverage of the literature. Also, our review includes studies that have been controlled for confounding factors, thereby reducing the potential for bias.

In conclusion, this review suggests that oral hygiene factors like periodontitis and tooth loss have an independent association with stroke. More studies, focused on different ABI other than stroke, are needed. Oral hygiene interventions (assisted or otherwise) should be part of the patients’ daily routine. Early diagnosis, prevention, and treatment may decrease the chances of developing chronic low-grade inflammation and therefore reduce the risk of stroke.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interests.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the support of Henrik Laursen (Region Midtjylland hospital, research librarian) with the development of electronic searches.

References

- 1.Dörfer CE, Becher H, Ziegler CM, Kaiser C, Lutz R, Jörss D, et al. The association of gingivitis and periodontitis with ischemic stroke. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.2004.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miniño AM, Arias E, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Smith BL. Deaths: final data for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002;50:1–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joshipura KJ, Hung H-C, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and incidence of ischemic stroke. Stroke J Cereb Circ. 2003;34:47–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000052974.79428.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oluwagbemigun K, Dietrich T, Pischon N, Bergmann M, Boeing H. Association between number of teeth and chronic systemic diseases: a cohort study followed for 13 years. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syrjänen J, Peltola J, Valtonen V, Iivanainen M, Kaste M, Huttunen JK. Dental infections in association with cerebral infarction in young and middle-aged men. J Intern Med. 1989;225:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arai K, Sumi Y, Uematsu H, Miura H. Association between dental health behaviours, mental/physical function and self-feeding ability among the elderly: a cross-sectional survey. Gerodontology. 2003;20:78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2003.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady M, Furlanetto D, Hunter RV, Lewis S, Milne V. Staff-led interventions for improving oral hygiene in patients following stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003864. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003864.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kothari M, Spin-Neto R, Nielsen JF. Comprehensive oral-health assessment of individuals with acquired brain-injury in neuro-rehabilitation setting. Brain Inj. 2016;30:1103–1108. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2016.1167244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kothari M, Pillai RS, Kothari SF, Spin-Neto R, Kumar A, Nielsen JF. Oral health status in patients with acquired brain injury: a systematic review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017;123:205–219.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO Oral health. Geneva, WHO, 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs318/en/ (cited Jul 21, 2017).

- 11.Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Flaxman A, Naghavi M, Lopez A, et al. Global Burden of Oral Conditions in 1990–2010. J Dent Res. 2013;92:592–597. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu T, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, Dorn JP, Falkner KL, Sempos CT. Periodontal disease and risk of cerebrovascular disease: the first national health and nutrition examination survey and its follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2749–2755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez M, Krall EA, Garcia RI, Vokonas PS, Dietrich T. Periodontitis and incidence of cerebrovascular disease in men. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:505–512. doi: 10.1002/ana.21742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grau AJ, Becher H, Ziegler CM, Lichy C, Buggle F, Kaiser C, et al. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. Stroke J Cereb Circ. 2004;35:496–501. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000110789.20526.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee H-J, Garcia RI, Janket S-J, Jones JA, Mascarenhas AK, Scott TE, et al. The association between cumulative periodontal disease and stroke history in older adults. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1744–1754. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sim S-J, Kim H-D, Moon J-Y, Zavras AI, Zdanowicz J, Jang S-J, et al. Periodontitis and the risk for non-fatal stroke in Korean adults. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1652–1658. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pradeep AR, Hadge P, Arjun Raju P, Shetty SR, Shareef K, Guruprasad CN. Periodontitis as a risk factor for cerebrovascular accident: a case-control study in the Indian population. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:223–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietrich T, Garcia RI. Associations between periodontal disease and systemic disease: evaluating the strength of the evidence. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2175–2184. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, Osinbowale O, Trevisan M, Levison ME, et al. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:2520–2544. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31825719f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odgaard L, Kothari M. Prevalence and association of oral candidiasis with dysphagia in individuals with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj. 2017 doi: 10.1080/02699052.2017.1407960. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loesche WJ, Schork A, Terpenning MS, Chen YM, Kerr C, Dominguez BL. The relationship between dental disease and cerebral vascular accident in elderly United States veterans. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:161–174. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kothari M, Madsen VLF, Castrillon EE, Nielsen JF, Svensson P. Spontaneous jaw muscle activity in patients with acquired brain injuries – preliminary findings. J Prosthodont Res. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpor.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration, editors. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coar JT, Sewell JP. Zotero: Harnessing the power of a personal bibliographic manager. Nurse Educ. 2010;35:205–207. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0b013e3181ed81e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oxman AD, Guyatt GH. Validation of an index of the quality of review articles. J Clin Epidemiol. 1991;44:1271–1278. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(91)90160-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leira Y, Seoane J, Blanco M, Rodríguez-Yáñez M, Takkouche B, Blanco J, et al. Association between periodontitis and ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol. DOI: 10.1007/s10654-016-0170-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Lafon A, Tala S, Ahossi V, Perrin D, Giroud M, Béjot Y. Association between periodontal disease and non-fatal ischemic stroke: a case-control study. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72:687–693. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2014.898089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim H-D, Sim S-J, Moon J-Y, Hong Y-C, Han D-H. Association between periodontitis and hemorrhagic stroke among Koreans: a case-control study. J Periodontol. 2010;81:658–665. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.090614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grau AJ, Buggle F, Ziegler C, Schwarz W, Meuser J, Tasman AJ, et al. Association between acute cerebrovascular ischemia and chronic and recurrent infection. Stroke J Cereb Circ. 1997;28:1724–1729. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.9.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taguchi A, Miki M, Muto A, Kubokawa K, Migita K, Higashi Y, et al. Association between oral health and the risk of lacunar infarction in Japanese adults. Gerontology. 2013;59:499–506. doi: 10.1159/000353707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elter JR, Offenbacher S, Toole JF, Beck JD. Relationship of periodontal disease and edentulism to stroke/TIA. J Dent Res. 2003;82:998–1001. doi: 10.1177/154405910308201212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyatani F, Kuriyama N, Watanabe I, Nomura R, Nakano K, Matsui D, et al. Relationship between Cnm-positive Streptococcus mutans and cerebral microbleeds in humans. Oral Dis. 2015;21:886–893. doi: 10.1111/odi.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Slowik J, Wnuk MA, Grzech K, Golenia A, Turaj W, Ferens A, et al. Periodontitis affects neurological deficit in acute stroke. J Neurol Sci. 2010;297:82–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nader A, Ghoreishizadeh A, Ayramlu H, Ghavimi M, Ghoreishizadeh M, Salehsaber F. Periodontal disease and risk of cerebral ischemic stroke. J Neurol Sci Turk. 2011;28:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 36.You Z, Cushman M, Jenny NS, Howard G, REGARDS Tooth loss, systemic inflammation, and prevalent stroke among participants in the reasons for geographic and racial difference in stroke (REGARDS) study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203:615–619. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pussinen PJ, Alfthan G, Rissanen H, Reunanen A, Asikainen S, Knekt P. Antibodies to periodontal pathogens and stroke risk. Stroke J Cereb Circ. 2004;35:2020–2023. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000136148.29490.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghizoni JS, Taveira LA de A, Garlet GP, Ghizoni MF, Pereira JR, Dionísio TJ, et al. Increased levels of Porphyromonas gingivalis are associated with ischemic and hemorrhagic cerebrovascular disease in humans: an in vivo study. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20:104–112. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572012000100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee Y-L, Hu H-Y, Huang N, Hwang D-K, Chou P, Chu D. Dental prophylaxis and periodontal treatment are protective factors to ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:1026–1030. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Söder B, Meurman JH, Söder P-Ö. Gingival inflammation associates with stroke – a role for oral health personnel in prevention: a database study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sen S, Sumner R, Hardin J, Barros S, Moss K, Beck J, et al. Periodontal disease and recurrent vascular events in stroke/transient ischemic attack patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:1420–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrison HI, Ellison LF, Taylor GW. Periodontal disease and risk of fatal coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1999;6:7–11. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hosomi N, Aoki S, Matsuo K, Deguchi K, Masugata H, Murao K, et al. Association of serum anti-periodontal pathogen antibody with ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:385–392. doi: 10.1159/000343659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diouf M, Basse A, Ndiaye M, Cisse D, Lo CM, Faye D. Stroke and periodontal disease in Senegal: case-control study. Public Health. 2015;129:1669–1673. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leira Y, López-Dequidt I, Arias S, Rodríguez-Yáñez M, Leira R, Sobrino T, et al. Chronic periodontitis is associated with lacunar infarct: a case-control study. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1572–1579. doi: 10.1111/ene.13080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Zambrano M, Del Brutto VJ. Severe edentulism is a major risk factor influencing stroke incidence in rural Ecuador (The Atahualpa Project) Int J Stroke. 2017;12:201–204. doi: 10.1177/1747493016676621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tonomura S, Ihara M, Kawano T, Tanaka T, Okuno Y, Saito S, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhage and deep microbleeds associated with cnm-positive Streptococcus mutans; a hospital cohort study. Sci Rep. DOI: 10.1038/srep20074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.National Health and Medical Research Council How to use the evidence: assessment and application of scientific evidence. 2009. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/cp69 (cited October 3, 2016).

- 49.Sfyroeras GS, Roussas N, Saleptsis VG, Argyriou C, Giannoukas AD. Association between periodontal disease and stroke. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:1178–1184. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lafon A, Pereira B, Dufour T, Rigouby V, Giroud M, Béjot Y, et al. Periodontal disease and stroke: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21:1155–1161. doi: 10.1111/ene.12415. e66–e67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Janket S-J, Baird AE, Chuang S-K, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:559–569. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khader YS, Albashaireh ZSM, Alomari MA. Periodontal diseases and the risk of coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases: a meta-analysis. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1046–1053. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.8.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scannapieco FA, Bush RB, Paju S. Associations between periodontal disease and risk for atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol Am Acad Periodontol. 2003;8:38–53. doi: 10.1902/annals.2003.8.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Syrjänen J, Valtonen VV, Iivanainen M, Hovi T, Malkamäki M, Mäkelä PH. Association between cerebral infarction and increased serum bacterial antibody levels in young adults. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;73:273–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1986.tb03275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joshipura KJ, Douglass CW, Willett WC. Possible explanations for the tooth loss and cardiovascular disease relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:175–183. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burt BA, Ismail AI, Morrison EC, Beltran ED. Risk factors for tooth loss over a 28-year period. J Dent Res. 1990;69:1126–1130. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690050201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miranda AF, de Paula RM, de Castro Piau CGB, Costa PP, Bezerra ACB. Oral care practices for patients in intensive care units: a pilot survey. Indian J Crit Care. 2016;20:267–273. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.182203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grap MJ, Munro CL, Ashtiani B, Bryant S. Oral care interventions in critical care: frequency and documentation. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12:113–118. discussion 119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Landström M, Rehn I-M, Frisman GH. Perceptions of registered and enrolled nurses on thirst in mechanically ventilated adult patients in intensive care units – a phenomenographic study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2009;25:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wårdh I, Hallberg LR, Berggren U, Andersson L, Sörensen S. Oral health care – a low priority in nursing. In-depth interviews with nursing staff. Scand J Caring Sci. 2000;14:137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wårdh I, Andersson L, Sörensen S. Staff attitudes to oral health care. A comparative study of registered nurses, nursing assistants and home care aides. Gerodontology. 1997;14:28–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1997.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones JA, Kressin NR, Miller DR, Orner MB, Garcia RI, Spiro A. Comparison of patient-based oral health outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:975–985. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000025596.05281.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Talbot A, Brady M, Furlanetto DLC, Frenkel H, Williams BO. Oral care and stroke units. Gerodontology. 2005;22:77–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2005.00049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lamont RJ, Yilmaz O. In or out: the invasiveness of oral bacteria. Periodontol 2000. 2002;30:61–69. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.03006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kozarov E, Sweier D, Shelburne C, Progulske-Fox A, Lopatin D. Detection of bacterial DNA in atheromatous plaques by quantitative PCR. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:687–693. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cavrini F, Sambri V, Moter A, Servidio D, Marangoni A, Montebugnoli L, et al. Molecular detection of Treponema denticola and Porphyromonas gingivalis in carotid and aortic atheromatous plaques by FISH: report of two cases. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:93–96. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]