Abstract

Background

Efavirenz (EFV) and boosted protease inhibitors (bPIs) are still the preferred options for firstline antiretroviral regimens (firstline ART) in Latin America and have comparable short-term efficacy. We assessed the long-term durability and outcomes of patients receiving EFV or bPIs as firstline ART in the Caribbean, Central and South America network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet).

Methods

We included ART-naïve, HIV-positive adults on EFV or bPIs as firstline ART in CCASAnet between 2000 and 2016. We investigated the time from starting until ending firstline ART according to changes of third component for any reason, including toxicity and treatment failure, death, and/or loss to follow-up. Use of a third-line regimen was a secondary outcome. Kaplan-Meier estimators of composite end points were generated. Crude cumulative incidence of events and adjusted hazard ratios (aHRs) were estimated accounting for competing risk events.

Results

We included 14 519 patients: 12 898 (89%) started EFV and 1621 (11%) bPIs. The adjusted median years on firstline ART were 4.6 (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.4–4.7) on EFV and 3.8 (95% CI, 3.8–4.0) on bPI (P < .001). Cumulative incidence of firstline ART ending at 10 years of follow-up was 32% (95% CI, 31–33) on EFV and 44% (95% CI, 39–48) on bPI (aHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78–0.97). The cumulative incidence rates of third-line initiation in the bPI-based group were 6% (95% CI, 2.4–9.6) and 2% (95% CI, 1.4–2.2) among the EFV-based group (P < .01).

Conclusions

Durability of firstline ART was longer with EFV than with bPIs. EFV-based regimens may continue to be the preferred firstline regimen for our region in the near future due to their high efficacy, relatively low toxicity (especially at lower doses), existence of generic formulations, and affordability for national programs.

Keywords: antiretroviral therapy, durability, HIV, Latin America, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, protease inhibitor

Life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLWH) increased substantially with the introduction of combined active antiretroviral therapy (cART) [1]. Consequently, assessing long-term treatment outcomes and regimen durability has become increasingly relevant. Patients still experience treatment modifications and interruptions for reasons that may include virological failure, adverse events, or poor adherence [2, 3]; and treatment modifications or interruptions may be associated with increased costs or adverse clinical outcomes. Efavirenz (EFV) has been, until now, the preferred option for the third component in first antiretroviral regimens (firstline ART) to treat HIV infection, according to the World Health Organization Consolidated Guidelines (WHO) [4] and several other cART guidelines from Latin American countries [5, 6].

In most clinical trials, before the introduction of integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), efavirenz showed better efficacy or noninferiority in suppressing HIV replication when compared with other regimens [7–9]. Randomized clinical trials, however, are typically conducted over 48- to 96-week periods and evaluate primarily rates of virological suppression in populations selected with stringent criteria. A recent meta-analysis using pooled data of 29 clinical trials evaluated the risk of death [10], AIDS progression, and treatment discontinuation in ART-naïve patients comparing non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), including EFV-based regimens, with boosted protease inhibitor (bPI)–based regimens, and it showed no statistically significant differences between regimens in any of the individual and combined outcomes.

Observational studies, in contrast to clinical trials, have the potential to offer valuable additional information with respect to real-life settings, such as durability of the regimen over longer periods of time, survival, and loss to follow-up. Cohort studies carried out in Latin America and the Caribbean have evaluated the reasons for change of firstline regimen in the short term [2, 11] and long term [3], the prevalence of use of third-line regimens [12], and clinical outcomes such as death, loss to follow-up, and virological suppression after 1 year of cART initiation [13, 14]. Nevertheless, long-term outcomes on firstline ART and other outcomes that are seldom measured in these studies, such as the probability of requiring a third-line regimen, may have significant economic and public health relevance. Therefore, in this study, we compared the durability of firstline ART according to the third component in a cohort from Latin America and the Caribbean, and explored the effect of the use of EFV vs bPI as a third component of firstline ART on the subsequent need of a third-line regimen over a long period of time.

METHODS

Study Design and Study Population

In this observational, retrospective cohort study, we included ART-naïve adults (18 years or older), living with HIV infection, who started their firstline ART between January 1, 2000, and June 30, 2016, at sites participating in the Caribbean, Central and South America network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet) cohort in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Honduras, Mexico, Peru, and Haiti. Patients were included if the third component of their firstline ART was either EFV or a bPI. Only lopinavir/ritonavir and atazanavir/ritonavir were considered qualifying bPIs for this study; 15 patients starting darunavir/ritonavir were excluded.

Definitions and Statistical Analyses

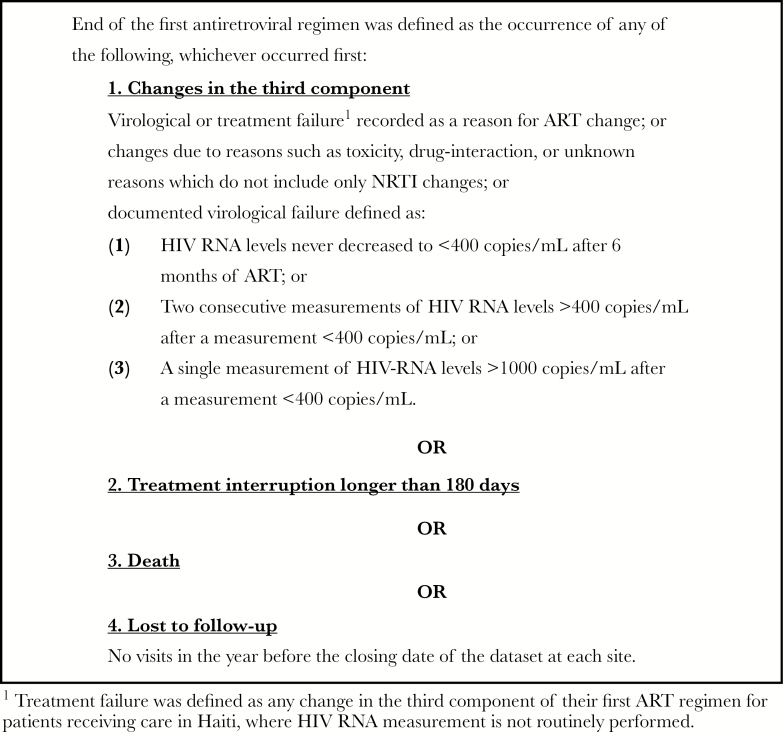

We compared the durability of EFV-based or bPI-based firstline ART by assessing the time from treatment initiation to the end of firstline ART. We defined the end of firstline ART as the occurrence of any of the following: (1) changes in third component for any reason (eg, virological or treatment failure [TF], toxicity, or drug interactions); (2) interruption of treatment longer than 180 days; (3) death; or (4) loss to follow-up (LTFU), whichever occurred first. Detailed definitions of specific events including virological failure and LTFU are given in Figure 1. Time in follow-up started on the date of firstline ART initiation and ended at the date of the first event of interest or the database closing date. (Database closing dates differed by study site and are included in the Supplemental Material.)

Figure 1.

Operational definition of end of the first antiretroviral treatment regimen.

The median time on the firstline ART was estimated as the time corresponding to the 50th percentile taken from a covariate-adjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Kaplan Meier curves were estimated adjusting for covariates at firstline ART initiation using inverse probability of treatment weights, defined as the inverse of the predicted probability of the patient getting their observed regimen (EFV vs bPI). These weights were produced by fitting a logistic regression model for the probability of starting a bPI regimen as firstline ART based on study site, date of ART initiation, sex, probable route of HIV transmission, age at ART initiation, CD4 at ART initiation, and nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) backbone of the regimen [15]. We evaluated the balance of baseline covariables among regimens in the weighted sample estimating standardized mean differences; results are available in Figure S8 (Supplementary Material). Analyses were repeated among those who were late ART initiators (LI, CD4 <200 cells/µL or AIDS-defining event [ADE]) and among those who were non-LI (CD4 ≥200 cells/µL and no previous ADE). In secondary analysis, we stratified the bPI group by type of PI (ATV/r: atazanavir/ritonavir vs LPV/r: lopinavir/ritonavir) to explore whether any differences with EFV could be attributed to either.

We also performed analyses that did not include death and LTFU as part of the outcome, but treated death and LTFU as competing events. In this second analysis, cumulative incidence of changing/interrupting firstline ART was estimated, accounting for competing events, both for the overall cohort and among LI and non-LI. We used a proportional subdistribution hazard regression model to assess the association between clinical and demographic variables on the time to ending firstline ART due to changes/interruptions in the third component [16]. We included sex, age, year of ART initiation, probable route of HIV transmission, CD4 count at ART initiation, ADE at ART initiation, and NRTI backbone of the regimen as covariables and stratified by site. CD4 count at ART initiation was the closest measurement to the date of ART initiation within 180 days prior to, or 30 days following, ART start. We calculated e-values to measure the strength of association on the risk ratio scale that an unmeasured confounder would need to have with both the regimen and the change/interruption of third component, conditional on the measured covariates, to explain away the observed association [17].

We performed a separate, unadjusted analysis to estimate the percentage of patients that required the initiation of a third-line ART regimen at any time point during follow-up, and the cumulative incidence of this event by firstline ART accounting for the competing events of death and LTFU. The initiation of a third-line regimen was defined as follows: (1) 2 previous ART regimen changes due to treatment failure and at least 1 of the drugs in the selected third regimen was etravirine, raltegravir, maraviroc, tipranavir, dolutegravir, or darunavir; or (2) 1 previous ART regimen change due to treatment failure and the use of at least 2 of the above-mentioned drugs in the selected third regimen.

In secondary analyses, we performed a cross-sectional analysis at different time points after firstline ART initiation (1, 3, 5, and 10 years) and took snapshots of patient status (remaining on firstline ART, LTFU, ART interrupted, change of third component, or death) by firstline ART group in subgroups of patients who started ART early enough to reach the potential follow-up time. For example, for the analysis looking at patient status after 1 year, we only included patients who started ART at least 1 year before the database closing date for their site, so that all included patients had the chance of being in follow-up at least 1 year. When death or LTFU occurred before a given time point, those events were considered the outcome at that time point even if the patient had presented a prior end of firstline ART event. A sensitivity analysis was done excluding patients from Haiti because viral load measurements were not routinely performed at that site.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from institutional review boards at each study site and at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Study Population

We included data on 14 519 patients: 12 898 (89%) started ART with an EFV-based regimen and 1621 (11%) with a bPI-based regimen. Of these, 920 (57%) started with LPV/r and 701 (43%) with ATV/r. Patients were followed for a median of 3.4 years (interquartile range [IQR], 1.5–6.2 years). The median time in follow-up was slightly longer for the EFV-based group (3.44 years; IQR, 1.5–6.3 years) than for the bPI-based group (3.16 years; IQR, 1.4–5.6 years; P < .001). Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients started on EFV-based regimens were on average 2 years older and more likely to be male (76% vs 59%) than patients starting a bPI-based regimen. Median CD4 count at ART initiation was lower among patients starting an EFV-based regimen (175 vs 217 cells/µL); 61% of patients starting an EFV-based regimen were late ART initiators (LI) compared with 49% starting a bPI-based regimen. There were also differences in the distribution of the type of NRTI backbone between those starting EFV- vs bPI-based regimens. The proportion of patients initiating EFV- vs bPI-based regimens differed between study sites (Table 1). Comparisons stratifying the bPI regimens are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Briefly, patients started on ATV/r were older, more frequently male, had higher baseline CD4 counts, and were more likely to be started with TDF- and ABC-based regimens than their counterparts.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics by Third Component of First ART Regimen

| EFV-Based | Boosted PI | Combined | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | (n = 12 898) | (n = 1621) | (n = 14 519) | P |

| Age at ART initiation, y | 37 (30–45) | 35 (29–44) | 37 (30–45) | <.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 9864 (76) | 956 (59) | 10 820 (75) | <.001 |

| CD4 at ART initiation, cells/µL | 175 (66–289) | 217 (79–351) | 178 (67–295) | <.001 |

| Missing CD4 at ART, n (%) | 1208 (9) | 203 (13) | 1411 (10) | |

| Late ART initiation, n (%) | 7863 (61) | 804 (49) | 8667 (60) | <.001 |

| Probable route of HIV transmission, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Heterosexual | 3874 (30) | 665 (41) | 4539 (31) | |

| MSM | 4100 (32) | 529 (33) | 4629 (32) | |

| Other | 130 (1) | 25 (2) | 155 (1) | |

| Unknown | 4794 (37) | 402 (25) | 5196 (36) | |

| NRTI backbone, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| 3TC/ABC | 483 (4) | 126 (8) | 609 (4) | |

| 3TC/AZT | 8234 (64) | 858 (53) | 9092 (63) | |

| 3TC/D4T | 744 (6) | 60 (4) | 804 (6) | |

| 3TC/TDF | 1754 (14) | 351 (22) | 2105 (14) | |

| FTC/TDF | 1683 (13) | 226 (14) | 1909 (13) | |

| Patients per site, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Argentina | 1680 (13) | 345 (21) | 2025 (14) | |

| Brazil | 2258 (18) | 507 (31) | 2765 (19) | |

| Chile | 1109 (9) | 186 (11) | 1295 (9) | |

| Haiti | 3824 (30) | 234 (14) | 4058 (28) | |

| Honduras | 800 (6) | 26 (2) | 826 (6) | |

| Mexico | 873 (7) | 145 (9) | 1018 (7) | |

| Peru | 2354 (18) | 178 (11) | 2532 (17) | |

| Year of ART initiation | 2009 (2007–2012) | 2011 (2008–2013) | <.001 |

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range). CCASAnet participating centers per country are: Hospital Fernandez and Centro Medico Huesped in Buenos Aires, Argentina; Instituto de Pesquisa Clinica Evandro Chagas, Fundacão Oswaldo Cruz in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Fundación Arriarán in Santiago, Chile; Le Groupe Haitien d’Etude du Sarcome de Kaposi et des Infections Opportunistes in Port-au-Prince, Haiti; Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social and Hospital Escuela Universitario in Tegucigalpa, Honduras; Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán in Mexico City, Mexico; and Instituto de Medicina Tropical Alexander von Humboldt in Lima, Peru.

Abbreviations: 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; AZT, zidovudine; D4T, stavudine; EFV, efavirenz; FTC, emtricitabine; late ART Initiation, CD4 <200 or AIDS-defining event at ART initiation; MSM, men having sex with men; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; TDF, tenofovir.

Durability of First ART Regimen

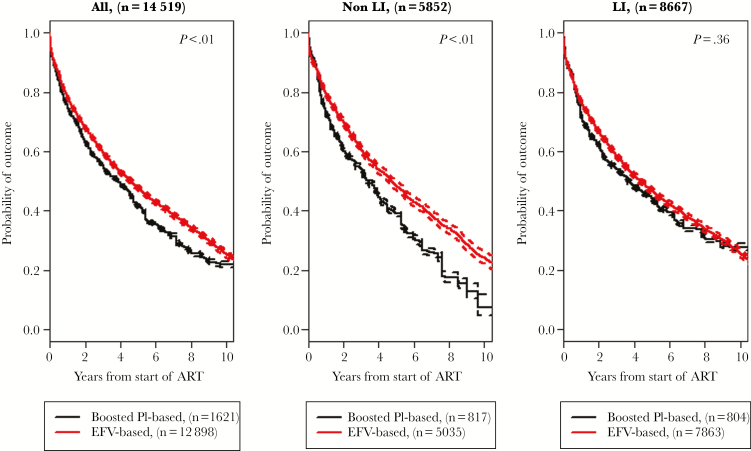

The adjusted median time to the end of the first ART regimen for any reason was 4.6 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 4.4–4.7 years) in the EFV-based group vs 3.8 years (95% CI, 3.8–4.0 years; P < .001) in the bPI-based group (Figure 2 A). In stratified analysis, the median durations of first ART were 4.0 years (95% CI, 3.3–4.5 years) on ATV/r and 2.9 years (95% CI, 2.4–3.2 years) on LPV/r. Among non-LI, the adjusted median duration of the first ART regimen was 4.7 years (95% CI, 4.5–5.0 years) for those who started with an EFV-based regimen vs 3.4 years (95% CI, 3.2–3.6 years) for those who started a bPI-based regimen (P < .01) (Figure 2B). The median time on first ART was 4.1 years (95% CI, 3.2–6.2 years) on ATV/r and 3.2 years (95% CI, 2.7–3.9 years) on LPV/r. Among LI, the median time to the end of the first ART regimen was 4.4 years (95% CI, 4.1–4.6 years) for the EFV-based group and 3.6 years (95% CI, 3.6–3.9 years) among those in the bPI-based group (P = .37) (Figure 2C). The median time on first ART was 3.8 years (95% CI, 3.1–4.9 years) on ATV/r and 2.2 years (95% CI, 1.8–3.1 years) on LPV/r. See Figure S1 in the Supplementary Material for stratified comparative analysis.

Figure 2.

Adjusted probability of first antiretroviral regimen (firstline ART) termination in the overall cohort, stratified based on stage of HIV-associated disease at firstline ART start (non-LI vs LI), by group of first treatment regimen (efavirenz vs boosted protease inhibitor). Abbreviations: EFV, efavirenz; LI, patients initiating with CD4 <200 cells/µL or AIDS-defining event; Non-LI, patients initiating with CD4 ≥200 cells/µL and no AIDS-defining event; PI, protease inhibitor.

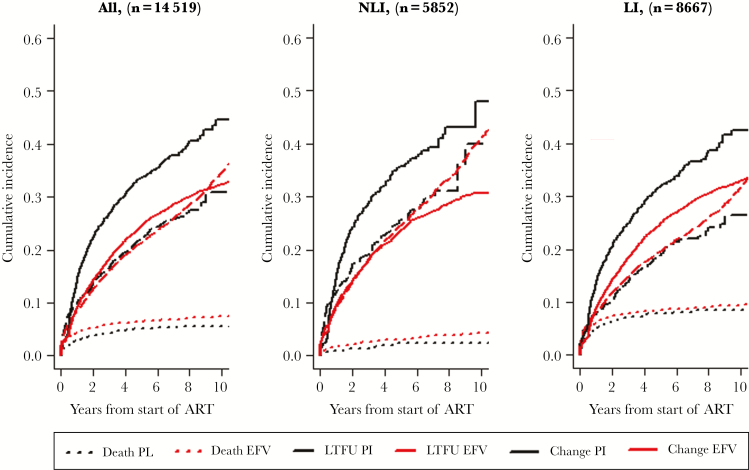

Treating death and loss to follow-up as competing events, the crude cumulative incidences of ending firstline ART 10 years after ART initiation were 32% (95% CI, 31%–33%) for those started on EFV and 44% (95% CI, 39%–48%) for those started on a bPI (P < .001). Among non-LI, cumulative incidence at 10 years was 31% (95% CI, 29%–33%) for EFV and 48% (95% CI, 37%–59%) for bPI (P < .01); among LI, cumulative incidence at 10 years was 33% (95% CI, 32%–34%) for EFV and 42% (95% CI, 37%–47%) for bPI (P < .01) (Figure 3). The adjusted hazard ratio for changing or interrupting the third component among patients starting EFV vs bPI was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.78–0.97; P = .016). This point estimate and 95% CI correspond with e-values of 1.41 and 1.17. Other covariables, including sex, age, men having sex with men (MSM) route of HIV transmission, and CD4 count at firstline ART, were also independently associated with the incidence of changing or interrupting the third component (Table 2). The results of the analysis stratifying bPI regimen in ATV/r and LPV/r are shown in Table S3.

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence for change of third component of firstline ART using death and loss to follow-up as competing events by treatment group (EFV vs bPI) in the overall cohort (A), and in analysis stratified by stage of HIV-associated disease at firstline ART initiation, for non-late ART initiators (B) or late ART initiators (C) over time. Abbreviations: bPI, boosted protease inhibitor; Change, includes changes in the third component of firstline ART for any reason or interruptions of treatment; EFV, efavirenz; firstline ART, first antiretroviral regimen; LI, patients initiating with CD4 <200 cells/µL or AIDS-defining event; LTFU, lost to follow-up, defined as no visits in the year before the closing date of data set for each site; Non-LI, patients initiating with CD4 >200 cells/µL and no AIDS-defining event.

Table 2.

Adjusted Hazard Ratio for Cumulative Incidence of Changes of Third Component by First Antiretroviral Regimen

| aHR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| EFV vs boosted PI | 0.88 (0.78–0.97) | .016 |

| Year of firstline ART | 0.99 (0.97–1.00) | .05 |

| Male | 0.79 (0.72–0.86) | <.001 |

| Age (per 10 y) | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) | <.001 |

| Route of HIV transmission | ||

| MSM vs heterosexual | 0.78 (0.71–0.86) | <.001 |

| Other vs heterosexual | 1.06 (0.79–1.41) | .70 |

| Unknown vs heterosexual | 0.89 (0.77–1.04) | .15 |

| CD4 count at ART initiation | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | .016 |

| ADE at ART initiation | ||

| ADE vs unknown | 0.94 (0.83–1.06) | .36 |

| Non-ADE vs unknown | 0.91 (0.82–1.01) | .09 |

| NRTI backbone | ||

| 3TC/ABC vs 3TC/AZT | 0.89 (0.75–1.07) | .22 |

| 3TC/D4T vs 3TC/AZT | 1.09 (0.94–1.26) | .24 |

| FTC/TDF vs 3TC/AZT | 0.74 (0.64–0.86) | <.001 |

| 3TC/TDF vs 3TC/AZT | 0.82 (0.72–0.93) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: 3TC, lamivudine; ABC, abacavir; ADE, AIDS-defining event; AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; AZT, zidovudine; D4T, stavudine; EFV, efavirenz; firstline ART, firstline antiretroviral regimen; FTC, emtricitabine; MSM, men having sex with men; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; TDF, tenofovir.

Reasons for Ending Firstline ART

The distribution of the reasons for ending the first ART regimen differed between the EFV and bPI groups (P < .001) (Table 3). There were 6914/12 898 (53%) events of firstline ART termination in the EFV group: 821 (12%) were deaths, 3040 (44%) losses to follow-up, 2894 (42%) changes in third component, and 159 (2%) ART interruptions. In the bPI-based group, we observed 928/1621 (57%) events: 77 (8%) were deaths, 343 (37%) losses to follow-up, 491 (53%) changes in third component, and 17 (2%) ART interruptions. The proportion of changes of the third component as firstline ART ending events due to treatment failure was significantly higher for bPI-based regimens than for regimens containing EFV in the overall cohort, and for both LI and non-LI (Table 3).

Table 3.

Number of Patients Ending First Antiretroviral Regimen by Reason of Ending in the Cohort and Stratifying by late ART Initiation

| All | Non-LI | LI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFV-Based (n = 12 898), n (%) |

Boosted PI (n = 1621), n (%) |

EFV-Based (n = 5035), n (%) |

Boosted PI (n = 817), n (%) |

EFV-Based (n = 7863), n (%) |

Boosted PI (n = 804), n (%) |

|

| Patients ending firstline ART | 6914 (53) | 928 (57) | 2378 (42) | 449 (50) | 4536 (58) | 479 (59) |

| Reason of ending | ||||||

| Death | 821 (12) | 77 (8) | 149 (6) | 15 (3) | 672 (15) | 62 (13) |

| LTFU | 3040 (44) | 343 (37) | 1190 (50) | 184 (41) | 1850 (41) | 159 (33) |

| Changes of third componenta | 2894 (42) | 491(53) | 978 (41) | 238 (53) | 1916 (42) | 253 (53) |

| Treatment failure | 1866 (27) | 340 (37) | 595 (25) | 179 (40) | 1271 (28) | 161 (34) |

| Other reasons | 1028 (15) | 155 (17) | 383 (16) | 59 (13) | 645 (14) | 92 (19) |

Percentages for reason of ending are relative to the total number of ending firstline ART.

Abbreviations: EFV, efavirenz; firstline ART, first antiretroviral regimen; LI, patients initiating with CD4 <200 cells/µL or AIDS-defining event; LTFU, lost to follow-up, defined as no visits in the year before the closing date of data set in each site; Non-LI, patients initiating with CD4 ≥200 cells/µL and no AIDS-defining event; PI, protease inhibitor.

aChanges of third component include changes for any reason; in this table, we show the changes due to treatment failure, which could be documented virological failures and virological or treatment failures recorded as reason for change. Other reasons include toxicity and drug interactions, and changes with reason unknown. ART interruption is defined as interruptions longer than 180 days.

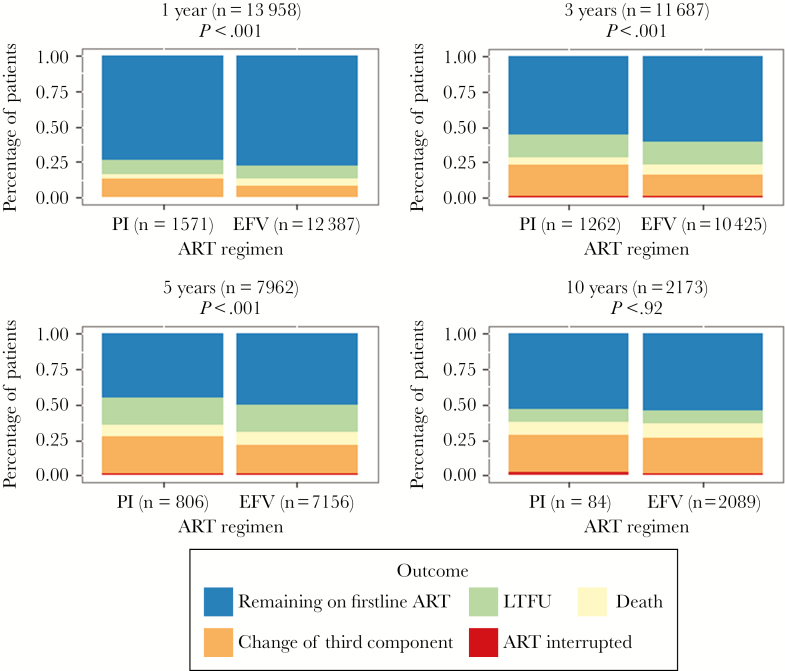

The distribution of different reasons for ending firstline ART at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years is shown in Figure 4. The percentage of patients remaining on firstline ART was nearly 5% higher in the EFV group than in the bPI group during the first 5 years, but only 1% at 10 years (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of individual outcomes by first antiretroviral regimen at 1, 3, 5, and 10 years after ART initiation. Abbreviations: ART interrupted, includes interruptions longer than 180 days; Change of third component, includes changes in the third component of firstline ART for any reason; EFV, efavirenz; firstline ART, first antiretroviral regimen; LTFU, lost to follow-up, defined as no visits in the year before the closing date of data set for each site; PI, protease inhibitor.

Need of Third-Line Regimen

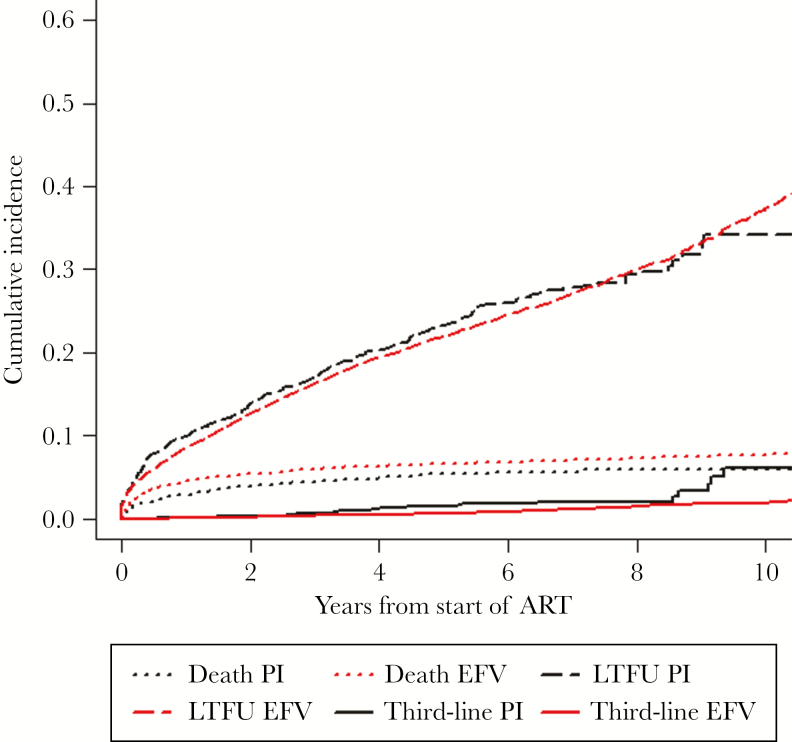

In the analysis of the need to start a third-line regimen, we observed 218 events of third-line initiation: 185 in the EFV-based group (1.43%) and 33 in the bPI-based group (2.03%; P = .07). Using competing events, the cumulative incidence of third-line initiation in the bPI-based group was 6% (95% CI, 2.4%–9.6%), and among the EFV-based group it was 2% (95% CI, 1.4%–2.2%; P < .01) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Cumulative incidence for use of a third-line ART regimen using death and loss to follow-up as competing events by first regimen treatment group (efavirenz vs boosted protease inhibitor). Abbreviations: bPI, boosted protease inhibitor; EFV, efavirenz; LTFU, lost to follow-up, defined as no visits in the year before the closing date of data set in each site; Third-line, use of a third-line regimen, defined as (1) 2 previous ART regimen changes due to treatment failure and at least 1 of these drugs in the selected third regimen, etravirine, raltegravir, maraviroc, tipranavir, dolutegravir, or darunavir; or (2) 1 previous ART regimen change due to treatment failure and the use of at least 2 of the above-mentioned drugs in the selected third regimen.

Sensitivity Analysis

In a sensitivity analysis excluding data of patients receiving care in Haiti because they did not routinely measure HIV-1 RNA, we included a total of 10 461 patients: 9074 (86.74%) in the EFV group and 1387 (13.26%) in the bPI group. The results were similar to the main analysis, except that the durability of the EFV-based regimen was statistically longer in both LI and non-LI. Details are shown in the Supplementary Material.

DISCUSSION

In this large, observational cohort study of people living with HIV and receiving care in Latin America, we found that in ART-naïve patients starting treatment, the median duration of EFV-based regimens was almost a year longer than boosted PI–based regimens. A lower incidence of changes in the third component for EFV regimens for any reason, rather than the number of deaths and losses to follow-up, seems to explain this difference. This difference was determined mainly by the significantly longer duration of EFV-based regimens than those receiving lopinavir/ritonavir, and to a lesser extent by differences with boosted atazanavir. In the main analysis, patients starting EFV without advanced HIV disease had a significantly longer durability of firstline ART. Among patients initiating ART with advanced disease (CD4 <200 cells/µL or ADE), those starting EFV also had a longer durability of firstline ART, although the association was no longer statistically significant. At different time points during follow-up, the proportion of patients remaining in firstline ART was significantly higher among patients who started EFV. In addition, third-line regimen use among subjects starting ART with EFV-based regimens during complete follow-up was significantly lower than among those starting a bPI-based regimen.

This study is consistent with previous clinical trials, observational cohort studies, and meta-analyses that separately have compared the short-term efficacy of EFV- vs bPI-based regimens to suppress HIV replication and time to regimen discontinuation or modification. Overall, treatment failure due to virological failure or treatment discontinuation is more common in patients starting ART with bPI regimens than those starting with EFV [18–21]. Nonetheless, information derived from clinical trials is limited because of the short-term follow-up [19, 20], small numbers of participants [18, 19, 21], and restrictive inclusion criteria [18–20] that may not allow for wide applicability in all contexts of routine clinical care [22]. Our results are also consistent with previous observations published by our group reporting that patients who had started bPI regimens were overrepresented as a group among those starting second-line regimens in CCASAnet centers [2].

The difference in durability among PLWH starting ART with advanced HIV-associated disease was not statistically significant, even though clinical trials in this population have found significant differences [19]. In a sensitivity analysis excluding Haiti, however, firstline EFV-based regimens had a longer durability in both LI and non-LI (see the Supplementary Materials). This discrepancy might be explained by clinical practice at the center in Haiti, where rather than routine viral load measurement, CD4 count and clinical status were used to monitor ART efficacy and to direct changes in regimen. In addition, bPI use in Haiti was extremely unusual, and our analyses may not have sufficiently adjusted for confounding variables. Other factors such as differences in study populations and estimands [23] and selection bias might also contribute to this discrepancy.

Our study adds to previous knowledge by showing that, over a 10-year period, in day-to-day routine care, starting treatment with EFV as the third component of a combined ART regimen had advantages over selected boosted PIs in terms of regimen durability in a cohort of patients from 7 Latin American and Caribbean countries. The longer durability of EFV-based regimens in this study, explained largely by differences with boosted lopinavir, was attributed to lower rates of treatment failure, which could be due to lower toxicity, lower rates of virological failure, or a combination of both. We consider that our definitions of durability, which includes a combination of several possible outcomes, and of the secondary outcome (need of a third-line regimen) are relevant from a public health and programmatic perspective because of the increased cost of switching a failing ART regimen and the use of broader options of active drugs in salvage regimens [12, 24]. In addition, we observed a small but statistically significant reduction in the subsequent need to use third-line drugs in the EFV-treated group. The small difference might be explained partially by the lack of access to third-line drugs in the region during the study period or to practice in the region where patients failing a bPI are more likely to escalate to third-line therapy than those failing EFV.

We acknowledge that these results may not be fully representative due to the limited sample of centers and the unique characteristics of the participating sites in CCASAnet, which are primarily academic centers. While we have discussed the issue of representativeness in other analyses by our group, we are uncertain how our results would vary had a wider variety of centers been included. Nonetheless, previous reports from other local and multinational groups in the region usually have been consistent with results reported from our centers [11, 13, 25–27]. Moreover, patients were likely started on bPI-based regimens for reasons not fully captured in our analyses. It is possible that unmeasured variables (ie, confounders) associated with both the choice of firstline ART and subsequent events may explain the differences between EFV- and bPI-based regimens seen in this study. For instance, young women were overrepresented among people starting boosted lopinavir-based regimens, which were recommended as the firstline regimen for reproductive-age women during the study period in several countries [28–32]. While we controlled for sex and age, we were not able to account for pregnancy status at ART initiation, but there were only 28 women with end of pregnancy registered as a reason for ending bPI (data not shown), which makes it unlikely to have had a strong confounding effect. In addition, because of limited data, we were unable to include tuberculosis information in our analyses. In the primary analysis, an unmeasured confounder with an association with both exposure and outcome of at least 1.41 (for the point estimate to be 1) or 1.17 (for the upper limit of the 95% CI to include 1) would be needed to explain away the observed association. It is quite possible that such an unmeasured confounder exists, which is a limitation of our study.

Finally, our study leaves unanswered questions that warrant further investigation. Due to the limited number and follow-up of patients started on INSTI, we did not compare the durability of this drug class in our study, even though these regimens are currently recommended as preferred initial ART regimens in high-income countries, and by the WHO as an alternative to EFV [4]. While our results support continuing use of EFV-based regimens as firstline ART over bPIs, particularly boosted LPV/r, they do not provide any information comparing EFV with INSTI. However, they suggest that in cases where EFV is not a valid option, skipping past bPI to Integrase inhibitor–based therapy may be warranted. Despite the preference of INSTI in firstline regimens in high-income countries [33], EFV-based regimens may continue to be preferred for our region in the future, due to their high efficacy, relatively low toxicity (especially at lower doses) [34], the existence of generic formulations, and most importantly, affordability for national programs.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, in our study, patients initiating ART with EFV-based regimens had longer durability of their first ART regimen and eventually required the use of a third-line ART regimen less frequently than patients starting ART with bPI-based regimens. Our results are relevant because in our region, as in other developing countries where the consolidated WHO recommendations for ART use are currently followed, EFV-based regimens are still the preferred options for first ART regimen. Our results strengthen and support current WHO recommendations, as well as most regional national guidelines.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online (http://ofid.oxfordjournals.org): results of the stratified analysis for Boosted-PI as ATV/r and LPV/r vs EFV and the sensitivity analysis to evaluate long-term outcomes among naïve patients initiating with EFV-based and Boosted-PI regimes, excluding Haiti.

Acknowledgments

Authors’ contributions. Study concept and design: Y.C.V., P.F.B.Z., B.C.R., J.S.M., B.E.S. Acquisition of data: B.C.R., B.G., M.W., J.W.P., D.P., E.G., C.M.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Y.C.V., P.F.B.Z., B.E.S. Drafting of the manuscript: Y.C.V., P.F.B.Z., B.C.R., J.S.M. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Y.C.V., P.F.B.Z., B.C.R., B.E.S., B.G., M.W., J.W.P., D.P., E.G., C.M., J.S.M. Statistical analysis: Y.C.V., P.F.B.Z., B.E.S. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Heatlh–funded Caribbean, Central and South America network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet), a member cohort of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (leDEA; U01AI069923). This award is funded by the following institutes: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Office of The Director (OD), National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH).

Potential conflicts of interest. Y.C.V., P.F.B.Z., B.E.S., B.G., J.W.P., D.P., E.G., and C.M. declare that they have no competing interests. J.S.M. has received lecture fees, sponsorship, and honoraria from Gilead, Stendhal, Abbvie, ViiV, Janssen, and MSD. M.W. has received congress attendance sponsorships from Gilead and MSD. B.C.R. has received lecture fees, sponsorship, and honoraria from Gilead, Stendhal, Abbvie, Janssen, and MSD.

The CCASAnet includes the following sites: Fundación Huesped, Argentina: Pedro Cahn, Carina Cesar, Valeria Fink, Omar Sued, Emanuel Dell’Isola, Hector Perez, Jose Valiente, Cleyton Yamamoto. Instituto Nacional de Infectologia-Fiocruz, Brazil: Beatriz Grinsztejn, Valdilea Veloso, Paula Luz, Raquel de Boni, Sandra Cardoso Wagner, Ruth Friedman, Ronaldo Moreira. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil: Jorge Pinto, Flavia Ferreira, Marcelle Maia. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Brazil: Regina Celia de Menezes Succi, Daisy Maria Machado, Aida de Fátima Barbosa Gouvêa. Fundación Arriarán, Chile: Marcelo Wolff, Claudia P. Cortes, Maria Fernanda Rodriguez, Gladys Allende. Les Centres GHESKIO, Haiti: Jean William Pape, Vanessa Rouzier, Adias Marcelin, Christian Perodin. Hospital Escuela Universitario, Honduras: Marco Tulio Luque. Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social, Honduras: Denis Padgett. Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, México: Juan

Sierra Madero, Brenda Crabtree Ramirez, Pablo F. Belaunzaran-Zamudio, Yanink Caro Vega. Instituto de Medicina Tropical Alexander von Humboldt, Peru: Eduardo Gotuzzo, Fernando Mejia, Gabriela Carriquiry. Vanderbilt University Medical Center, USA: Catherine C. McGowan, Bryan E. Shepherd, Timothy Sterling, Karu Jayathilake, Anna K. Person, Peter F. Rebeiro, Mark Giganti, Jessica Castilho, Stephany N. Duda, Fernanda Maruri, Hilary Vansell.

References

- 1. Palella FJ Jr, Delaney KM, Moorman AC et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:853–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cesar C, Shepherd BE, Krolewiecki AJ et al. ; Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV Research (CCASAnet) Collaboration of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) Program Rates and reasons for early change of first HAART in HIV-1-infected patients in 7 sites throughout the Caribbean and Latin America. PLoS One 2010; 5:e10490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wolff M, Shepherd BE, Cortés C et al. ; Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV Epidemiology Clinical and virologic outcomes after changes in first antiretroviral regimen at 7 sites in the Caribbean, Central and South America Network. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016; 71:102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO. The use of antirretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/. Accessed 23 August 2017.

- 5. CENSIDA. Guía de Manejo Antirretroviral de las Personas con VIH Available at: http://www.censida.salud.gob.mx/interior/guiasmanuales.html. Accessed 4 July 2017.

- 6. SADI. Consenso argentino de terapía antirretroviral 2014–2015 Available at: https://www.dropbox.com/s/xol78s0j5mkmdf2/consenso%202014–2015.pdf?dl=0. Accessed 4th July 2017.

- 7. Daar ES, Tierney C, Fischl MA et al. ; AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5202 Team Atazanavir plus ritonavir or efavirenz as part of a 3-drug regimen for initial treatment of HIV-1. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154:445–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Echeverría P, Negredo E, Carosi G et al. Similar antiviral efficacy and tolerability between efavirenz and lopinavir/ritonavir, administered with abacavir/lamivudine (Kivexa), in antiretroviral-naïve patients: a 48-week, multicentre, randomized study (Lake Study). Antiviral Res 2010; 85:403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miró JM, Manzardo C, Pich J et al. ; Advanz Study Group Immune reconstitution in severely immunosuppressed antiretroviral-naive HIV type 1-infected patients using a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor-based or a boosted protease inhibitor-based antiretroviral regimen: three-year results (The Advanz Trial): a randomized, controlled trial. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2010; 26:747–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borges ÁH, Lundh A, Tendal B et al. Nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor- vs ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor-based regimens for initial treatment of HIV Infection: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized trials. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 63:268–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tuboi SH, Schechter M, McGowan CC et al. Mortality during the first year of potent antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected patients in 7 sites throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009; 51:615–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cesar C, Shepherd BE, Jenkins CA et al. ; Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV Epidemiology (CCASAnet) Use of third line antiretroviral therapy in Latin America. PLoS One 2014; 9:e106887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Angriman F, Belloso WH, Sierra-Madero J et al. Clinical outcomes of first-line antiretroviral therapy in Latin America: analysis from the LATINA retrospective cohort study. Int J STD AIDS 2016; 27:118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cesar C, Koethe JR, Giganti MJ et al. ; Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV epidemiology (CCASAnet) and North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) Health outcomes among HIV-positive Latinos initiating antiretroviral therapy in North America versus Central and South America. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19:20684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med 2015; 34:3661–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999; 94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 17. VanderWeele TJ, Ding P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: introducing the E-value. Ann Intern Med 2017; 167(4):268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riddler SA, Haubrich R, DiRienzo AG et al. ; AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study A5142 Team Class-sparing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2095–106.18480202 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sierra-Madero J, Villasis-Keever A, Méndez P et al. Prospective, randomized, open label trial of Efavirenz vs Lopinavir/Ritonavir in HIV+ treatment-naive subjects with CD4+<200 cell/mm3 in Mexico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53:582–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Juday T, Grimm K, Zoe-Powers A et al. A retrospective study of HIV antiretroviral treatment persistence in a commercially insured population in the United States. AIDS Care 2011; 23:1154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Esposito A, Floridia M, d’Ettorre G et al. Rate and determinants of treatment response to different antiretroviral combination strategies in subjects presenting at HIV-1 diagnosis with advanced disease. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. López-Martínez A, O’Brien NM, Caro-Vega Y et al. Different baseline characteristics and different outcomes of HIV-infected patients receiving HAART through clinical trials compared with routine care in Mexico. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 59:155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hernán MA, Hernández-Díaz S. Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clin Trials 2012; 9:48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caro JJ, O’Brien JA, Migliaccio-Walle K, Raggio G. Economic analysis of initial HIV treatment. Efavirenz- versus indinavir-containing triple therapy. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19:95–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Crabtree-Ramírez B, Caro-Vega Y, Shepherd BE et al. ; CCASAnet Team Cross-sectional analysis of late HAART initiation in Latin America and the Caribbean: late testers and late presenters. PLoS One 2011; 6:e20272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Celi AP, Greco M, Martinez E et al. ; for the Latin American HIV Workshop Study Group Presentation to care with advanced HIV disease is still a problem in Latin America. J Int AIDS Soc 2016; 19(Suppl 2S1):35. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Magis-Rodríguez CL, Villafuerte-García A, Cruz-Flores RA, Uribe-Zúñiga P. Inicio tardío de terapia antirretroviral en México. Salud Publica Mex 2015; 57(Suppl 2): S127–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ministério da Saúde. Recomendacoes para Terapia Antiretroviral en Adultos infectados pelo HIV Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/brazil_art.pdf. Accessed 27 November 2017.

- 29. Ministerio de Salud. Manejo de los pacientes adultos con infección por VIH Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/argentina_art.pdf. Accessed 27 November 2017.

- 30. Ministerio de Salud. Peru. Norma técnica para el tratamiento Antiretroviral de gran actividad-TARGA en adultos infectados por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/peru_art.pdf. Accessed 27 November 2017.

- 31. MINSAL. Chile. Guía Clínica Sindrome de Inmunodeficiencia adquirida VIH/SIDA Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/chile_art.pdf. Accessed 27 November 2017.

- 32. MSPP. Manuel de Normes de Prise en Charge Clinique et Thérapeutique des Adultes et Adolescents Vivant avec le VIH Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/haiti_art.pdf. Accessed 27 November 2017.

- 33. WHO. Transition to new antiretrovirals in HIV programmes Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/255888/1/WHO-HIV-2017.20-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 27 November 2017.

- 34. Carey D, Puls R, Amin J et al. Efficacy and safety of efavirenz 400 mg daily versus 600 mg daily: 96-week data from the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, non-inferiority ENCORE1 study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015; 15:793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.