Summary

Background

The perinatal period is a time of high risk for onset of depressive disorders and is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, including maternal suicide. Perinatal depression comprises a heterogeneous group of clinical subtypes, and further refinement is needed to improve treatment outcomes. We sought to empirically identify and describe clinically relevant phenotypic subtypes of perinatal depression, and further characterise subtypes by time of symptom onset within pregnancy and three post-partum periods.

Methods

Data were assembled from a subset of seven of 19 international sites in the Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium. In this analysis, the cohort was restricted to women aged 19–40 years with information about onset of depressive symptoms in the perinatal period and complete prospective data for the ten-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS). Principal components and common factor analysis were used to identify symptom dimensions in the EPDS. The National Institute of Mental Health research domain criteria functional constructs of negative valence and arousal were applied to the EPDS dimensions that reflect states of depressed mood, anhedonia, and anxiety. We used k-means clustering to identify subtypes of women sharing symptom patterns. Univariate and bivariate statistics were used to describe the subtypes.

Findings

Data for 663 women were included in these analyses. We found evidence for three underlying dimensions measured by the EPDS: depressed mood, anxiety, and anhedonia. On the basis of these dimensions, we identified five distinct subtypes of perinatal depression: severe anxious depression, moderate anxious depression, anxious anhedonia, pure anhedonia, and resolved depression. These subtypes have clear differences in symptom quality and time of onset. Anxiety and anhedonia emerged as prominent symptom dimensions with post-partum onset and were notably severe.

Interpretation

Our findings show that there might be different types and severity of perinatal depression with varying time of onset throughout pregnancy and post partum. These findings support the need for tailored treatments that improve outcomes for women with perinatal depression.

Funding

Janssen Research & Development.

Introduction

In recent decades, a robust literature has documented the perinatal period as a time of high risk for onset of depressive disorders with substantial morbidity for mother, infant, and family that includes increased risk for low birthweight and prematurity, impaired mother-infant attachment, and infant malnutrition during the first year of life.12 Maternal suicide is a leading cause of maternal mortality.3 Perinatal depression, broadly defined by WHO as onset of a major depressive episode during pregnancy or the first 12 months post partum, has a lifetime prevalence of 10–15% in developed countries2 and higher risk in low-income countries.4 The greatest point prevalence for onset of symptoms is the acute post-partum period,5 but there is growing evidence that many women have onset of symptoms during pregnancy.6 The public health importance of identifying women who have perinatal depression was highlighted by new recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force for screening for depression during pregnancy and post partum.7 These recommendations are consistent with guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK,8 the Australian Perinatal Depression Initiative,9 and WHO recommendations.10

An analysis of data from the international Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium, which represents 19 institutions in seven countries, showed substantial heterogeneity in symptoms of perinatal depression.11 This study used latent class analysis and described three specific latent classes (subtypes) of women with post-partum depression who differed by symptom severity, timing of onset (pregnancy vs post partum), history of previous mood or anxiety disorder, pregnancy or obstetric complications, and presence of suicidal ideation. These findings supported the need for further investigation to increase our understanding of the different phenotypes and type and quality of presentation associated with perinatal depression in women with onset during pregnancy versus post partum. These findings extended previous work documenting that comorbid anxiety is an important symptom in women with the most severe illness (eg, worry or ruminating thoughts).12 Additionally, these findings were consistent with results of a clinical trial that showed differential treatment response by the time of symptom onset in women with post-partum depression.13

Anxiety and mood symptoms in perinatal depression have not been adequately described. We postulated that women who become depressed during pregnancy will differ in type and quality of presentation compared with those with post-partum onset. We wanted to examine this important issue in the PACT Consortium dataset, which had not been previously addressed in the first PACT study.11 We hypothesised that the underlying causes for onset and quality of symptoms across the perinatal period could be different on the basis of underlying pathophysiological mechanisms such as the hormonal fluctuations that characterise the perinatal period.14 Therefore, rather than focus on traditional diagnostic criteria for perinatal depression that do not account for co-occurring anxiety symptoms, we sought to examine the symptom constructs described in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) research domain criteria (RDoC).15 The NIMH RDoC was developed to create a framework for research on pathophysiology that helps to inform future neuroscience-based diagnostic classification systems and ultimately leads to novel treatment and detection of subtypes for treatment selection.16 Application of the RDoC framework to examine the performance of mapping, screening, or diagnostic measures of depression to RDoC constructs has been an informative approach in other studies.17 We examined the RDoC functional constructs (ie, negative valence and arousal or regulatory systems)16 on the basis of patient report of symptoms assessed with the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in the PACT Consortium.18 Examination of the EPDS factor structure has been described in the literature with consistent reports of subscales measuring mood and anxiety.19 A few studies have also described a potential third EPDS subscale for anhedonia20 or suicidal thoughts.21 We focused on the RDoC functional constructs of negative valence (anxiety) and arousal because the symptom of anxiety is often a hallmark phenotypic feature of the perinatal period.

The primary objective of our study was to empirically identify and describe clinically relevant subtypes of perinatal depression on the basis of RDoC symptom dimensions in the PACT Consortium dataset, and to further characterise the subtypes by time of symptom onset in each trimester of pregnancy and three post-partum periods (0 to <4 weeks, ≥4 to <8 weeks, and ≥8 weeks).

Methods

Participants

Data were assembled from a subset of seven of 19 international sites in the PACT Consortium, which contributed anonymised clinical data. PACT’s mission, data collection, and aggregation are described in detail elsewhere.11,22 Participants included women with reported depression in the postnatal period and were recruited from several settings including psychiatric clinics, obstetric clinics, primary care, and community advertisements. Each site obtained consent from participants and approval from its institutional review board for data sharing. In this subset of the PACT sample, the cohort was restricted to women aged 19–40 years with information about onset of depressive symptoms in the perinatal period and complete prospective data for the ten-item EPDS, which was obtained between Oct 15, 2012, and Oct 27, 2013. The most severe EPDS rating was selected for women with longitudinal PACT records. Timing of depression onset was submitted to the PACT Consortium either as a clinician assessed or self-reported onset depending on the site.

The EPDS is one of the most widely studied and validated instruments for assessing perinatal depressive symptoms.23 On the basis of distributions seen in this sample, the EPDS scores were categorised into four severity levels reported in the literature (no depression, EPDS score 0–9; mild to moderate, 10–16; moderate to severe, 17–21; and very severe, 22–30).11,24

Statistical analysis

Our analytical approach extends the first PACT study in several ways. We began with an examination of the dimensionality of the EPDS. Using the factor score symptom dimensions as quantitative traits, subtypes of women having similar symptom dimensions were identified. The subtypes were profiled according to demographics, pregnancy characteristics, perinatal complications, and previous history of a mood or anxiety disorder. This approach allowed identification of subtypes using EPDS symptom dimensions and not by differences in perinatal or demographic features. This analysis builds on the previous PACT study by including a crosssectional examination of the EPDS symptom dimensions with reported onset of symptoms across each trimester of pregnancy and three post-partum periods. We selected the three post-partum periods (0 to <4 weeks, ≥4 to <8 weeks, and ≥8 weeks) on the basis of the DSM-5 and WHO ICD-10 criteria for perinatal depression.25,26 Univariate and bivariate descriptive statistics described the characteristics of the overall sample and subtypes. All analyses were done with SAS version 9.4.

Analysis of symptom dimensionality and subtypes

Principal components and common factor analysis based on the tetrachoric correlation matrix were used to identify symptom dimensions in the EPDS. The RDoC functional constructs of negative valence and arousal were applied to the EPDS dimensions that aligned with the symptom dimensions of interest—states of depressed mood, anhedonia, and anxiety. Quantitative scores were assigned to each study participant on each of the three dimensions. These scores were subsequently used to identify subtypes of women with similar patterns on the three dimensions by k-means clustering. A five subtype solution met the statistical criterion of the cubic clustering criterion (CCC),27 which applies an algorithm (examples include k-means and Wards) to minimise the within-cluster sum of squares and squared Euclidean distances. These five subtypes aligned with clinically relevant phenotypes observed in post-partum depression. The subtypes were described with descriptive statistics and ANOVA with post-hoc Scheffe comparison of means to identify which pairs of subtypes were significantly different. The Scheffe is a statistical method applied after an ANOVA to identify which groups are significantly different when more than two groups are being tested. Additional details of these methods are described in the appendix.

Classification algorithms

Scoring algorithms for the three symptom dimensions and subtype membership (logistic regression probability of membership in each subtype) were developed to allow for replication in other samples. Additional details of the analyses and algorithms are presented in the appendix, enabling researchers and clinicians using the EPDS to examine the usefulness of this approach in their unique settings.

Results

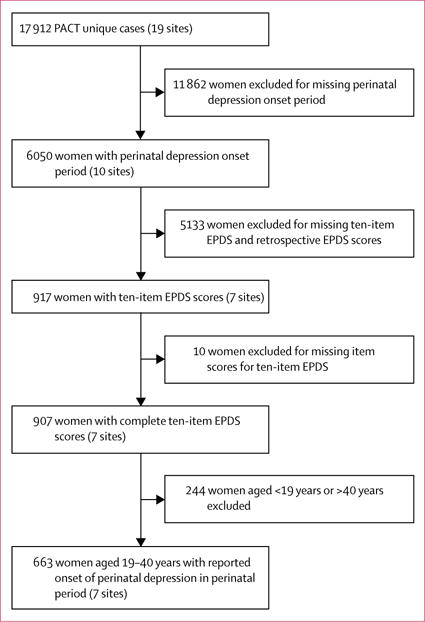

Data for 663 women (mean age 32 years [SD 4.5]) who met the study inclusion criteria were included in these analyses (figure 1). All data were from seven of the 19 sites. 11 of the 13 demographic and perinatal characteristics reported in table 1 had 70% or more data available. The proportion of missing data ranged from 2% for marital status to 49% for the birth complication of pre-eclampsia. The median EPDS measurement used in these analyses was done 4·5 months post partum (median 135 days [IQR 51–215]). At the time of EPDS assessment, 167 (25%) women reported having no depressive symptoms (EPDS 0–9), 142 (21%) reported mild to moderate symptoms (EPDS 10–16), 299 (45%) reported moderate to severe symptoms (EPDS 17–21), and 54 (8%) had very severe symptoms (EPDS 22–30).

Figure 1. Participant selection.

EPDS=Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. PACT=Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment Consortium. The perinatal depression period includes each trimester of pregnancy and three post-partum periods (0 to <4 weeks, ≥4 to <8 weeks, and ≥8 weeks).

Table 1.

Demographic and perinatal characteristics

| Anxious depression | Anhedonia | Resolved depression (n=175) |

Total (n=663) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Severe (n=211) | Moderate (n=123) | Anxious (n=79) | Pure (n=75) | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 183/211 (87%) | 89/114 (78%) | 61/73 (84%) | 46/65 (71%) | 10/13 (77%) | 390/476 (82%) |

| African American | 16/211 (8%) | 13/114 (11%) | 6/73 (8%) | 12/65 (18%) | 2/13 (15%) | 49/476 (10%) |

| Other | 12/211 (6%) | 12/114 (11%) | 6/73 (8%) | 7/65 (11%) | 1/13 (8%) | 38/476 (8%) |

|

| ||||||

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | 19/209 (9%) | 16/118 (14%) | 33/76 (43%) | 14/71 (20%) | 28/88 (32%) | 110/562 (20%) |

| College | 123/209 (59%) | 68/118 (58%) | 37/76 (49%) | 40/71 (56%) | 30/88 (34%) | 298/562 (53%) |

| Professional | 67/209 (32%) | 34/118 (29%) | 6/76 (8%) | 17/71 (24%) | 30/88 (34%) | 152/562 (27%) |

|

| ||||||

| Married or cohabiting | 176/210 (84%) | 104/123 (85%) | 71/78 (91%) | 60/74 (81%) | 147/164 (90%) | 558/649 (86%) |

|

| ||||||

| Parity, two or more | 135/211 (64%) | 76/117 (65%) | 25/46 (54%) | 48/72 (67%) | 106/173 (61%) | 390/619 (63%) |

|

| ||||||

| Caesarean section | 77/207 (37%) | 40/119 (34%) | 11/41 (27%) | 23/72 (32%) | 42/166 (25%) | 193/605 (32%) |

|

| ||||||

| SCID LT mood* | 150/199 (75%) | 67/100 (67%) | 10/14 (71%) | 37/57 (65%) | 7/12 (58%) | 271/382 (71%) |

|

| ||||||

| SCID LT anxiety† | 124/199 (62%) | 78/100 (78%) | 4/14 (29%) | 48/57 (84%) | 3/12 (25%) | 257/382 (67%) |

|

| ||||||

| Maternal obesity | 33/200 (17%) | 12/110 (11%) | 1/20 (5%) | 17/65 (26%) | 8/161 (5%) | 71/556 (13%) |

|

| ||||||

| Pregnancy complications‡ | 64/204 (31%) | 21/115 (18%) | 4/45 (9%) | 25/71 (35%) | 20/174 (11%) | 134/609 (22%) |

|

| ||||||

| Obstetric complications§ | 101/210 (48%) | 53/117 (45%) | 5/47 (11%) | 26/73 (36%) | 9/124 (7%) | 194/571 (34%) |

|

| ||||||

| Gestational diabetes | 14/191 (7%) | 8/110 (7%) | 3/45 (7%) | 1/61 (2%) | 18/174 (10%) | 44/581 (8%) |

|

| ||||||

| Pre-eclampsia | 14/188 (7%) | 2/90 (2%) | 1/5 (20%) | 4/44 (9%) | 0/8 | 21/335 (6%) |

|

| ||||||

| Post-partum haemorrhage | 4/191 (2%) | 3/100 (3%) | 1/43 (2%) | 2/49 (4%) | 2/80 (3%) | 12/463 (3%) |

|

| ||||||

| Breastfeeding | 181/211 (86%) | 97/114 (85%) | 33/43 (77%) | 61/71 (86%) | 100/117 (85%) | 472/556 (85%) |

Data are n/N (%). SCID LT=structured clinical interview for DSM-IV, lifetime.

Included endorsement at any time of any of the following DSM-IV lifetime diagnoses: post-partum depression, major depressive disorder, depression disorder not otherwise specified, and dysthymia.

Included endorsement at any time of any one or more of the following DSM-IV lifetime diagnoses: generalised anxiety disorder, panic, agoraphobia, post-traumatic stress disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, anxiety not otherwise specified, and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Included endorsement of any of the five items for gestational hypertension, maternal obesity, pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes, and high-risk pregnancy status.

Included endorsement of any of the five items for fetal stress, post-partum haemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes, delivery type, or low birthweight.

We identified five subtypes of perinatal depression that differed in severity and type of symptoms. These subtypes are described by the onset of symptoms spanning across the pregnancy trimesters and early versus later post-partum periods. Ethnicity, education level, marital status, and medical and pregnancy complications contributed to distinguishing the subtypes (table 1).

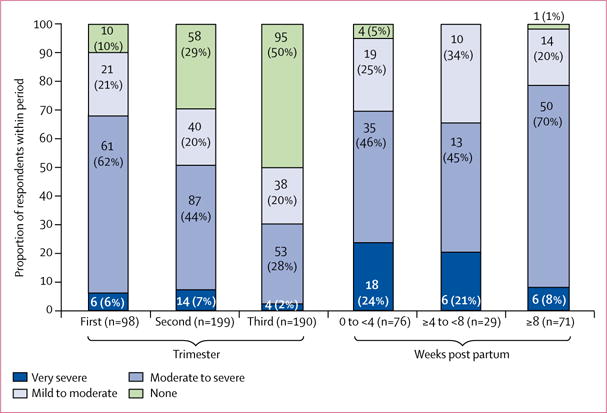

The timing of onset of depressive symptoms during the perinatal period was associated with EPDS score. 68% of women with first trimester onset had ongoing moderate to severe or very severe symptoms at the time of EPDS assessment (figure 2). However, 95 (50%) of 190 women with third trimester onset had remitted completely by that time. Later onset of depressive symptoms during pregnancy was associated with a better outcome at the post-partum EPDS assessment. Women with onset of depression in the second or third trimesters were more likely to be in the mild to moderate category or none category at assessment (50% of women with onset in the second trimester and 70% with onset in the third trimester) compared with women with onset in the first trimester (32%). Onset of symptoms of depression in the post-partum period was associated with more severe depression. More than 20% of women with post-partum depression who reported onset within the first 8 weeks post partum had very severe symptoms at assessment; this proportion is nearly four times higher than that for women who had onset of depression during pregnancy (figure 2).

Figure 2. Edinburgh postnatal depression scale score by time of onset of perinatal depressive symptoms.

Column data are n (%).

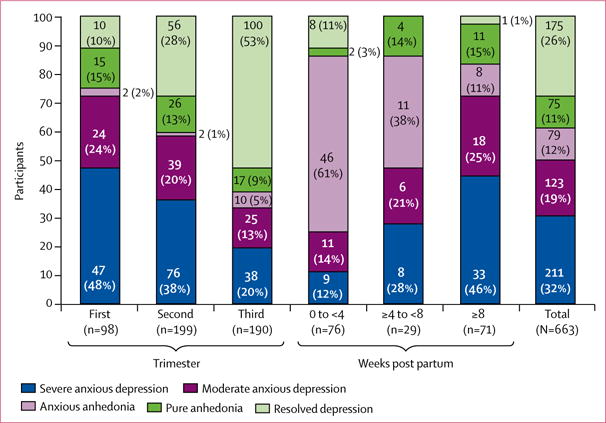

The three symptom dimensions of depressed mood, anxiety, and anhedonia on the basis of EPDS items are presented in table 2. The three symptom dimensions identified five subtypes of women by use of k-means clustering on the quantitative scores. The subtypes differed on symptom dimensions by type of depression and severity of illness. The five subtypes are labelled 1 to 5 (table 3). Subtype 1 is characterised as severe anxious depression and subtype 2 as moderate anxious depression. These two subtypes shared anxious depression symptoms of comorbid anxiety yet differed in severity of depression and of anxiety. Subtypes 3 and 4 are broadly characterised as anhedonia. Subtype 3 was defined as anxious anhedonia and subtype 4 was defined as pure anhedonia. Women with subtype 5, resolved depression, reported onset of symptoms during the perinatal period, which had resolved at the time of EPDS assessment. In our sample, half the women had either the severe (211 [32%]) or moderate (123 [19%]) anxious depression subtypes. 175 (26%) participants had the subtype of resolved depression, 79 (12%) had anxious anhedonia, and 75 (11%) had pure anhedonia.

Table 2.

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) factor structure

| Depressed mood | Anxiety | Anhedonia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal thoughts (10) | 97* | −17 | −2 |

|

| |||

| Unhappy: crying (9) | 79* | 19 | 4 |

|

| |||

| Unhappy: difficulty sleeping (7) | 76* | 15 | 4 |

|

| |||

| Felt sad or miserable (8) | 51* | 44* | −2 |

|

| |||

| Felt scared or panicky (5) | 52* | 41* | 0 |

|

| |||

| Anxious or worried (4) | 3 | 74* | 1 |

|

| |||

| Things on top of me (difficulty coping; 6) | 11 | 68* | −7 |

|

| |||

| Looked forward with enjoyment (2) | −2 | 2 | 83* |

|

| |||

| Been able to laugh (1) | −7 | 8 | 81* |

|

| |||

| Blamed myself unnecessarily (3) | 13 | −17 | 57* |

EPDS item number is given in parentheses. Table entries are the standardised rotated factor loadings multiplied by 100.

Primary contributor to each factor.

Table 3.

Comparison of factor scores among the subtypes of perinatal depression

| Subtype 1 | Subtype 2 | Subtype 3 | Subtype 4 | Subtype 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressed mood (F=1174.45; df=4662; p<00001) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Severe anxious depression (1) | ‥ | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | <0.0001* |

| Moderate anxious depression (2) | <0.0001 | ‥ | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | <0.0001* |

| Anxious anhedonia (3) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ‥ | 0.67 | <0.0001* |

| Pure anhedonia (4) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.67 | ‥ | <0.0001* |

| Resolved depression (5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ‥ |

|

| |||||

| Anxiety (F=617.78; df=4662; p<00001) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Severe anxious depression (1) | ‥ | <0.0001* | 0.0059* | <0.0001* | <0.0001* |

| Moderate anxious depression (2) | <0.0001 | ‥ | <0.0001 | <0.0001* | <0.0001* |

| Anxious anhedonia (3) | 0.0059 | <0.0001* | ‥ | <0.0001* | <0.0001* |

| Pure anhedonia (4) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ‥ | 0.0089* |

| Resolved depression (5) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0089 | ‥ |

|

| |||||

| Anhedonia (F=600.81; df=4662; p<00001) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Severe anxious depression (1) | ‥ | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0080 |

| Moderate anxious depression (2) | <0.0001* | ‥ | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001* |

| Anxious anhedonia (3) | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | ‥ | 0.82 | <0.0001* |

| Pure anhedonia (4) | <0.0001* | <0.0001* | 0.82 | ‥ | <0.0001* |

| Resolved depression (5) | 0.0080 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ‥ |

Factor scores are compared across subtypes using general linear models with Scheffe-adjusted post-hoc pair-wise comparisons for significant mean differences.

Subtype comparison for which the row subtype has a significantly higher score and more severe symptoms than the column subtype.

Severe anxious depression (subtype 1) has significantly higher depressed mood and anxiety ratings compared with all the other subtypes (2, 3, 4, and 5), but does not have higher scores than any subtype on the anhedonia symptom dimension (table 3). Similarly, women with resolved depression (subtype 5) have significantly lower ratings than all other subtypes for all of the dimensions, apart from higher scores on the anhedonia factor than the severe anxious depression subtype.

Table 4 shows the distribution of EPDS scores in each subtype with overall EPDS means, the proportion of each subtype across the severity categories, and the mean anxiety subscale scores. Notably, 98% of the severe anxious depression subtypes are in the moderate to severe or very severe EPDS categories. The anxious anhedonia subtype has the highest proportion of women in the very severe EPDS category. The final item in the EPDS assesses thoughts of self-injury. Such thoughts are prominent in the subtypes with comorbid anxiety, and to a lesser extent in the pure anhedonia subtype. Both of the subtypes characterised with anxiety symptoms (severe anxious depression and anxious anhedonia) have higher scores on the EPDS anxiety subscale.28

Table 4.

Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) categories, self-harm, and anxiety subscale in the subtypes of perinatal depression

| Severe anxious depression (n=211) |

Moderate anxious depression (n=123) |

Anxious anhedonia (n=79) |

Pure anhedonia (n=75) |

Resolved depression (n=175) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total score | 20.2 (1.5) | 16 (2.7) | 19.2 (3.8) | 14.9 (3.2) | 4.1 (3.0) |

| None | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (5%) | 164 (94%) |

| Mild to moderate | 4 (2%) | 63 (51%) | 19 (24%) | 45 (60%) | 11 (6%) |

| Moderate to severe | 176 (83%) | 59 (48%) | 38 (48%) | 26 (35%) | 0 |

| Very severe | 31 (15%) | 1 (1%) | 22 (28%) | 0 | 0 |

| Thought of harming self: quite often or sometimes | 209 (99%) | 94 (76%) | 3 (4%) | 35 (47%) | 1 (1%) |

| EPDS anxiety subscale* | 6.0 (1.1) | 4.7 (1.5) | 6.5 (1.7) | 4.2 (1.6) | 1.9 (1.6) |

Data are mean (SD) or n (%). EPDS scores grouped by none (0–9), mild to moderate (10–16), moderate to severe (17–21), and very severe (22–30).

EPDS anxiety subscale: EPDS items 3 (blamed myself), 4 (anxious or worried), and 5 (scared or panicky).

The severe anxious depression subtype is more likely to have depression onset in the first trimester or more than 8 weeks after birth than during the other perinatal periods (figure 3). A similar pattern is seen in women characterised by the subtype moderate anxious depression. Women with the subtype of anxious anhedonia were more likely to have onset of illness during the first (0 to <4 weeks; 61%) and second (≥4 to < 8 weeks; 38%) post-partum periods than during the other perinatal periods; few women with this subtype had onset in the periods during pregnancy. Few women characterised by pure anhedonia have onset of illness during the immediate post-partum period (0 to <4 weeks), but they are fairly evenly represented across the other perinatal periods we examined. Women with resolved depression subtype reported onset of depression predominantly in the third trimester of pregnancy and not in the post-partum periods.

Figure 3. Subtype distribution in the three trimesters of pregnancy and three post-partum periods.

Column data are n (%). A bar representing the total sample is included on the right for comparison purposes. If there was no difference by onset period, each of the other bars would reflect the distribution of the total sample.

Discussion

We sought to empirically identify and describe clinically relevant subtypes of perinatal depression in a subset of the PACT Consortium dataset, and further characterise these subtypes by time of symptom onset within each of the three trimesters of pregnancy and three post-partum periods. Our study extends previous work11 by including an examination of onset and quality of depression symptoms during several perinatal periods. By use of a framework derived from the RDoC principles, we described three underlying symptom constructs or dimensions in the EPDS: depressed mood, anxiety, and anhedonia.

The subtypes that emerged from clustering women on patterns of factor scores were anxious depression, both severe and moderate, and anhedonia, alone and in combination with anxiety. We also found a subtype of women whose depression started in the second or third trimester of pregnancy and had resolved at the time of EPDS measurement. Women with the subtype anxious anhedonia were more likely to have onset of illness during the first and second post-partum periods than during the other perinatal periods. Onset in the first trimester occurred for many of the women with the subtype of anxious depression. Some of these women might have had depression before pregnancy. Additionally, our results suggest that comorbid anxiety and anhedonia are prominent symptoms associated with both pregnancy and obstetric complications and, in a subgroup of women, onset of depression.

We also noted that onset of symptoms in the first 8 weeks of the post-partum period was associated with more severe depression, characterised as subtype anxious anhedonia. Moreover, 20% of women were still categorised as very severe at the post-partum EPDS assessment; an increase of almost four times compared with women who had onset of depression during pregnancy. In view of the enormous hormonal fluctuations that occur in the transition from pregnancy to post partum,14 it is reasonable to speculate that there could be important conceptual and biological differences underlying the severity and phenomenology of depression between women with onset of symptoms during pregnancy versus women with post-partum onset. Furthermore, there is a growing literature on the important role of reproductive hormones in modulating neural circuits and biological systems implicated in depression, suggesting that the characteristic hormone instability of the perinatal period could contribute to mood dysregulation in post-partum depression.14,29

Our study has several limitations. First, this is a secondary analysis of existing data; the sample includes seven of 19 sites in PACT and is a subset of the full PACT Consortium. The analysis was restricted to seven sites able to answer the time of onset question spanning the prenatal and post-partum period. PACT was originally created by aggregating extant data across international independent sites with various protocols to examine the phenotypic heterogeneity of post-partum depression. These protocols had inherent differences, including selection criteria, recruitment settings, and variables collected. Missing data occurred in two ways: (1) extraction from the PACT parent larger dataset created a subset for which the data were not missing at random since they were not collected at the site level (ie, when time of reported onset or complete ten-item EPDS prospective data were not available for a particular site, though this was not the case for the seven sites included in the analysis); and (2) data were missing at random within the seven sites for demographic and perinatal characteristics because they were not collected or available to PACT at the time of the analyses. This additional layer of missing data might further bias results and the characteristics are only presented as numbers and percentages. Therefore, missing data could contribute to ascertainment bias, which is an inherent concern when pooling data, and could potentially influence the robustness of the findings. Second, the EPDS ratings occurred 4.5 months post partum and thus are a cross-sectional examination rather than a longitudinal assessment. Third, study protocols had interstudy differences including ascertainment criteria, recruitment settings, and the variables collected. Such differences and missing sociodemographic data could contribute to bias and question the strength of the results. Fourth, most of the data are from white women and different ethnicities might have different illness patterns; we also cannot exclude the role of socioeconomic status and country of origin on our findings, thereby potentially limiting generalisability.22 Fifth, the analyses were limited to variables collected across studies, and onset of depression included both clinical and self-report assessments. Sixth, other attributes relevant to identifying and characterising subtypes of perinatal depression could exist. Few data were available for history of stressful life events, such as abuse or trauma, which could have a role in perinatal depression. Finally, we do not have detailed information about the pre-pregnancy depression status of the women in the dataset. Women who reported first trimester onset of symptoms and continued to be symptomatic over time might be more chronically depressed and might have had depressive symptoms before pregnancy.

However, we believe that the strengths of the results outweigh the limitations as an important hypothesis-generating foundation for future work. The strengths of this study include the novel approach to further examine subtypes of post-partum depression from a subset of the PACT Consortium with diverse characteristics for sites and countries and detailed symptom assessment using standardised measures. Validation of our findings is important, including the factor structure, subtypes, and associations with onset period.

In conclusion, we applied three underlying symptom dimensions measured by the EPDS that correlate with the RDoC framework to further examine perinatal depression, and identified five distinct subtypes with clear differences in time of depression onset in the perinatal period. Anxiety and anhedonia emerged as prominent symptom dimensions with post-partum onset and were notably severe. Women with post-partum onset of symptoms had severe and persistent symptoms. Women with onset in their first trimester also remained highly symptomatic in the post-partum period. Therefore, to deliver the most effective treatment, future clinical and research efforts should focus on the potential phenomenological and biological differences characterising onset of depression during pregnancy versus the post-partum period by use of prospective and longitudinal approaches. The recent development of guidelines in many countries on screening and treatment for perinatal depression provides a strong mandate to improve mental health care for all perinatal women. Consequently, development of effective screening strategies across a range of global settings that allow for the delivery of targeted therapies to women with different clinical phenotypes and severity of perinatal depression is imperative. These strategies must address the complexities associated with differences in time of symptom onset during the perinatal period and the diverse symptom constructs including anxiety, low mood, and anhedonia.

Supplementary Material

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We did two comprehensive searches to identify all relevant articles. First, we searched PubMed with the keywords “perinatal depression”, “postpartum depression”, “time of onset”, “pregnancy”, and “phenotypes” from inception until Feb 6, 2017. We did not restrict by year of publication and included all published articles. Next, we searched PsycInfo with the same keywords. The search yielded 38 articles from PubMed and four additional articles from PsycInfo that were applicable to our study objective. Previous work in this area is scant and few studies have examined the differences between women who develop depression during pregnancy compared with women who develop symptoms in the post-partum period. Furthermore, previous studies are limited by either very small sample sizes or inadequate phenotyping by time of symptom onset. Overall, research that investigates symptom constructs that may differentiate meaningful differences between depression during pregnancy versus post partum is rare, and no previous studies have examined the time of symptom onset in each trimester of pregnancy and three post-partum periods (0 to <4 weeks, ≥4 to <8 weeks, and ≥8 weeks) in relation to specific symptom dimensions that are based on a framework to understand the underlying pathophysiology.

Added value of this study

The Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium includes anonymised data from 19 international sites. We used data from seven of these sites to examine the time of onset of symptoms in the perinatal period. We examined National Institute of Mental Health research domain criteria (RDoC) functional constructs (ie, negative valence and arousal or regulatory systems) on the basis of patient report of symptoms assessed with the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in the PACT Consortium. We found evidence for three underlying dimensions of depressed mood, anxiety, and anhedonia in perinatal depression. On the basis of these dimensions, we identified five distinct subtypes of perinatal depression that had clear differences in symptom quality and time of onset. Anxiety and anhedonia emerged as prominent symptom dimensions with post-partum onset and were notably severe. Our findings have important public health implications to address the morbidity and mortality associated with perinatal depression. First, clinicians should be aware that different types and severity of perinatal depression exist, with varying time of onset throughout pregnancy and post partum. Second, we identified five distinct subtypes of perinatal depression and found clear differences related to time of depression onset in the perinatal period.

Implications of all the available evidence

There is growing evidence that a one-size-fits-all approach can no longer be applied to adequately meet the mental health needs of women with perinatal psychiatric illness. Different types and severities of perinatal depression exist. Further research into tailoring treatment on the basis of subtype to improve outcomes for women with different phenotypes and severity of perinatal depression is needed.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Mental Health supports TM-O, DR, PFS, and SM-B, (1R01MH104468-01), ER-B (K23MH080290, and a young investigator award from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation), KS (5K23MH086689), JP (K23 MH074799-01A2), VB (FP7-Health-2007 project no 222963), MO’H (MH50524 NIMH), KLW (5R01MH60335, NIMH, 5R01MH071825 NIMH, 5R01MH075921 NIMH, and 5-2R01MH057102), SJR and HT (ZonMW 10.000.1003, NIMH K23 MH097794, and NIH UL1 TR000161), and PS (ZIA MH002865-09 BEB). KMD is supported by the Worcester Foundation for Biomedical Research. CNE is supported by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals and a young investigator award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. GA and ED are supported by the French Ministry of Health (PHRC 98/001) and Mustela Foundation. BP is supported by the Geestkracht program of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (10-000-1002) and VU University Medical Centre, GGZ Geest, Arkin, Leiden University Medical Centre, GGZ Rivierduinen, University Medical Centre in Groningen, Lentis, GGZ Fries land, GGZ Drenthe, IQ Healthcare, Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research, and Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction. CG is supported by South Carolina Clinical and Translational Research Institute (UL1 TR000062) and Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (K12 HD055885). ZS is supported by the National Institutes for Health (P50 MH-77928 and P50 MH 68036). IJ is supported by the National Centre for Mental Health Wales.

MW reports employment at Janssen Research & Development, KMD reports research grant support from Sage Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. JP reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, and Johnson & Johnson, and research grant support from Sage Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. JP has a patent for Epigenetic Biomarkers of Postpartum Depression issued to Kaminsky and Payne. JN reports grants and personal fees from Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, and Wyeth, along with research grants from Takeda and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. CNE reports grants and personal fees from Sage Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. ZS reports grants from Janssen, and other from Sage Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. PFS reports personal fees from Pfizer outside the submitted work. DR reports personal fees and other from Sage Therapeutics, outside the submitted work. KW reports employment at Janssen Research & Development. SM-B reports research grant funding to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from Janssen during the conduct of this study for biostatistical support. SM-B reports research grant support from Sage Therapeutics, outside the submitted work.

Footnotes

Contributors

The individual studies contributing to the PACT analyses were led by ER-B, KS, VB, KMD, JP, MA, GA, PM, BP, AB, SR, CG, CNE, PS, KLW, ZS, IJ, PFS, DR, SM-B, and MO’H. Together with the core statistical analysis group led by KTP, MW, and SM-B, this group comprised the management group led by KTP and SM-B who were responsible for the management of the project and the overall content of the manuscript. KLW and MW also provided input on the manuscript, data analyses, and figures. The PACT phenotype committee comprised ER-B, KS, JP, VB, KMD, MA, DJN, GA, and SM-B. The executive and coordinating committee comprised JPS, KLW, ZS, IJ, DR, PFS, and SM-B. The remaining authors contributed to the recruitment or data processing for the contributing components of the PACT secondary analyses. SM-B and KTP with input from MW and KLW took responsibility for the primary drafting of the manuscript that was shaped by the phenotype and executive committees. All other authors saw, had the opportunity to comment on, and approved the final draft.

Declaration of interests

All other collaborators declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Karen T Putnam, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Marsha Wilcox, Janssen Research & Development, Titusville, NJ, USA.

Emma Robertson-Blackmore, Family Medicine Residency, Halifax Health, Daytona Beach, FL, USA.

Katherine Sharkey, Department of Internal Medicine and Psychiatry, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

Veerle Bergink, Department of Psychiatry/Psychology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Trine Munk-Olsen, Department of Economics and Business-National Centre for Integrated Register-based Research, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Kristina M Deligiannidis, Departments of Psychiatry and Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine, Glen Oaks, NY, USA.

Jennifer Payne, Department of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Margaret Altemus, Department of Psychiatry, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York City, NY, USA.

Prof Jeffrey Newport, Department of Psychiatry, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA.

Gisele Apter, Erasme Hospital, Paris Diderot University, Paris, France.

Emmanuel Devouche, Erasme Hospital, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France.

Alexander Viktorin, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

Patrik Magnusson, Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

Prof Brenda Penninx, Department of Psychiatry, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Prof Anne Buist, University of Melbourne, Women’s Mental Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Justin Bilszta, University of Melbourne, Women’s Mental Health, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

Prof Michael O’Hara, Department of Psychology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Prof Scott Stuart, Department of Psychology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Rebecca Brock, Department of Psychology, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA.

Sabine Roza, Department of Psychiatry/Psychology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Prof Henning Tiemeier, Department of Psychiatry/Psychology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, Netherlands.

Constance Guille, Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

Prof C Neill Epperson, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Deborah Kim, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Prof Peter Schmidt, National Institutes of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Pedro Martinez, National Institutes of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Arianna Di Florio, Cardiff University School of Medicine, Institute of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Cardiff, UK.

Prof Katherine L Wisner, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Asher Center for the Study and Treatment of Depressive Disorders, Chicago, IL, USA.

Prof Zachary Stowe, Department of Psychiatry, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR, USA.

Prof Ian Jones, Cardiff University School of Medicine, Institute of Psychological Medicine and Clinical Neuroscience, Cardiff, UK.

Prof Patrick F Sullivan, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USADepartment of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden.

Prof David Rubinow, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Kevin Wildenhaus, Janssen Research & Development, Titusville, NJ, USA.

Samantha Meltzer-Brody, Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

References

- 1.Parsons CE, Young KS, Rochat TJ, Kringelbach ML, Stein A. Postnatal depression and its effects on child development: a review of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Br Med Bull. 2012;101:57–79. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johannsen BM, Larsen JT, Laursen TM, Bergink V, Meltzer-Brody S, Munk-Olsen T. All-cause mortality in women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:635–42. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14121510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sawyer A, Ayers S, Smith H. Pre- and postnatal psychological wellbeing in Africa: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2010;123:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. New parents and mental disorders: a population-based register study. JAMA. 2006;296:2582–89. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, Groom HC, Burda BU. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:388–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: clinical management and service guidance. Clinical guideline CG192. 2014 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG192 (accessed March 27, 2017) [PubMed]

- 9.Australian Government Department of Health. National Perinatal Depression Initiative. 2013 http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/mental-perinat (accessed Aug 30, 2016)

- 10.WHO. WHO recommendations on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/health-promotion-interventions/en/ (accessed March 27, 2017) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium. Heterogeneity of postpartum depression: a latent class analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:59–67. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00055-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller ES, Hoxha D, Wisner KL, Gossett DR. Obsessions and compulsions in postpartum women without obsessive compulsive disorder. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2015;24:825–30. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.5063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hantsoo L, Ward-O’Brien D, Czarkowski KA, Gueorguieva R, Price LH, Epperson CN. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial of sertraline for postpartum depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2014;231:939–48. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3316-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiller CE, Meltzer-Brody S, Rubinow DR. The role of reproductive hormones in postpartum depression. CNS Spectr. 2015;20:48–59. doi: 10.1017/S1092852914000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Insel TR, Cuthbert BN. Medicine. Brain disorders? Precisely. Science. 2015;348:499–500. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ostergaard SD, Bech P, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Rush AJ, Fava M. Brief, unidimensional melancholia rating scales are highly sensitive to the effect of citalopram and may have biological validity: implications for the research domain criteria (RDoC) J Affect Disord. 2014;163:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–86. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthey S, Fisher J, Rowe H. Using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale to screen for anxiety disorders: conceptual and methodological considerations. J Affect Disord. 2013;146:224–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuohy A, McVey C. Subscales measuring symptoms of non-specific depression, anhedonia, and anxiety in the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Clin Psychol. 2008;47:153–69. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.2008.tb00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ross LE, Gilbert Evans SE, Sellers EM, Romach MK. Measurement issues in postpartum depression part 1: anxiety as a feature of postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6:51–57. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Florio A, Putnam K, Altemus M, et al. The impact of education, country, race and ethnicity on the self-report of postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Psychol Med. 2017;47:787–99. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ji S, Long Q, Newport DJ, et al. Validity of depression rating scales during pregnancy and the postpartum period: impact of trimester and parity. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:213–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JJ, La Porte LM, Saleh MP, et al. Suicide risk among perinatal women who report thoughts of self-harm on depression screens. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:885–93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO. The international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. (ICD-10) [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. (DSM-5) [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute. The cubic clustering criterion. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthey S. Using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale to screen for anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:926–31. doi: 10.1002/da.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deligiannidis KM, Sikoglu EM, Shaffer SA, et al. GABAergic neuroactive steroids and resting-state functional connectivity in postpartum depression: a preliminary study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:816–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.