Abstract

Period of Custodial Care Only:

The magnificent “Institute of Mental Health” has its history almost from 1795 when the East India company appointed Surgeon Valentine Conolly to be in charge of a “House for accommodating persons of unsound mind.” After a few transitions, backed by a government order for the construction of a lunatic asylum in a 66 1/2 acre site, the asylum started functioning from 1871. The period of about six decades from its inception could be referred to as “the period of custodial care.” However, the quality of care for the general medical problems gradually improved with the creation of separate facilities for some common ailments and also one for seriously ill. Separate wards were also conceptualized for criminal patients and female inmates.

Towards Modern Comprehensive Patient Care:

Thanks to Government sanctions, the staff strength gradually increased with regularization of bed strength to 1800, and by 1948-1957, the hospital had 14 medical officers and a host of other staff. The period from 1939 to 1948 witnessed the introduction of electroconvulsive therapy and insulin coma therapy including the modified one and also insulin histamine therapy. During the prephenothiazine era, the drugs used were barbiturates, paraldehyde, opiates, and Rauwolfia serpentina, which were discontinued after the use of Chlorpromazine from 1954. Psychosurgery was also undertaken in selected cases from 1948, but the procedure went out of vogue soon due to the quality of outcome being poor and development of complications. Rehabilitation of patients got a fillip with the introduction of occupation therapy in 1949 and industrial therapy center in 1970. Extension of psychiatric services to general hospitals began from 1949.

Advances in Academic Spheres And Research Activities:

Regular training was imparted to paramedical and undergraduate medical students from 1948. The institute had the privilege of hosting the Annual National Conference of Indian Psychiatric Society - 1957. The institute also spearheaded in several pioneering researches such as insulin coma therapy, syphilis, and Alzheimer's dementia, to name a few. The pivotal role played by the State Psychiatric Institutes in patient care, training, and research, should speak for adequate empowerment of these government institutes.

Keywords: Asylum, mental hospital, rehabilitation, research, therapy

INTRODUCTION

The Government Mental Hospital, Madras, presently the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), Chennai, is one of the oldest and largest in our country, nay, in South Asia, rendering psychiatric care to the mentally ill in Tamil Nadu. Its hoary past extends beyond the year 1871 when this hospital was built at the present site and the inmates were also from the neighboring areas of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Odisha in the days before the state's reorganization on a linguistic basis in 1957.

A recall of the history of the Government Mental Hospital, Madras, reflects the evolution of the management of mental diseases in Southern India during the past two centuries. They represent the sweat and toil of those men and women who not only served these institutions to the best of their abilities, with the knowledge and expertise of their respective eras but also put in their own contributions for the well-being of the patients in their care.

The writing of histories of institutions is not very popular in our country. We have made a humble effort to rectify this attitude by documenting the history of this prestigious hospital. Many former students of this institute are practicing worldwide whose nostalgic feelings can be satiated through this communication. It may also have a sobering effect on the future generations of students of psychiatry and allied disciplines who pass through the portals of the institution to learn that they stand on the shoulders of worthy men. The aim of this article is also to interest the intelligent layperson in the historical activities of this institute during the first two centuries of its inception.

DEVELOPMENT OF INFRASTRUCTURAL FACILITIES

As early as 1795, the East India Company, the then administrative authority for Fort St. George and surrounding area, appointed Surgeon Dr. Valentine Conolly who was the Secretary of the Hospital Board to be in charge of a “House for accommodating persons of unsound mind.” The premises were taken out on lease for a period of 25 years for a rent of Rs 825/month. Subsequently, Surgeon Maurice Fitzgerald and later Dr. John Goulde held charge who were succeeded by Dr. Dalton. Dr. Dalton who was in charge from 1807 to 1815 rebuilt the premises, and the institution came to be called as “Dalton's Mad House” with 54 inmates cared for in it. However, over crowding led to the removal of four harmless inmates to a home a few miles away that was amalgamated with Monegar Choultry in Royapuram. However, they were transferred back to the old asylum in Kilpauk, which was expanded by renting two adjacent buildings. By this time, the Government had sanctioned in G.O. No. 20, Judicial dated January 7, 1867, the construction of a lunatic asylum on 66½ acre site in Lococks Gardens, just outside the then municipal limits.

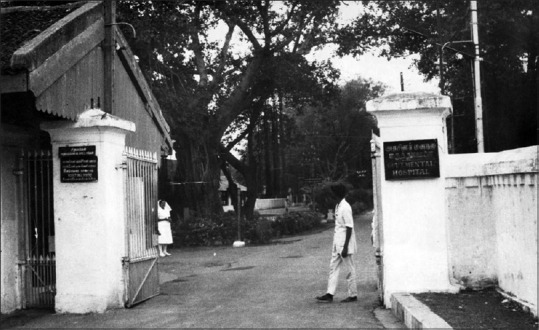

The asylum started functioning in the new premises on May 15, 1871 [Figure 1] with 145 patients, and Surgeon John Murray, as superintendent with residential quarters inside the premises. The buildings were put up on the cottage or pavilion system with blocks for 12–15 persons in each block fairly close by [Figures 2 and 3]. The wells inside the compound provided water till 1896 when the municipality took over this responsibility. The year 1892 saw the transfer in of all “criminal lunatics” from the districts and increase in staff strength was made with additional buildings including cottages for paying patients. Although a small number of those admitted could be sent back to their homes as “recovered,” the vast majority had to stay on in the asylum for the rest of their lives, and consequently, the word “Asylum” came to have a bad association. It was then, the year 1922 witnessed the change in name of the institution from “Government Lunatic Asylum” to “The Government Mental Hospital.” However, it was rechristened in 1977 as “IMH,” by the then Hon’ble Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu Dr. M.G. Ramachandran [Figure 4].

Figure 1.

Government Mental Hospital

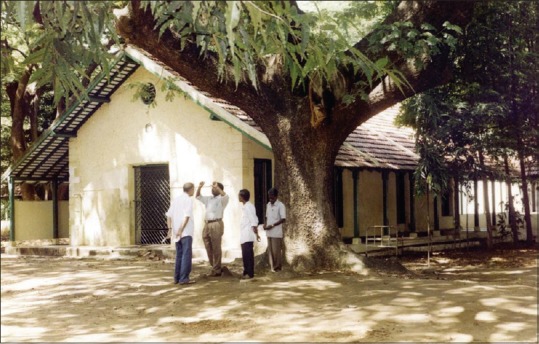

Figure 2.

Outside view of a block

Figure 3.

Inside view of a block

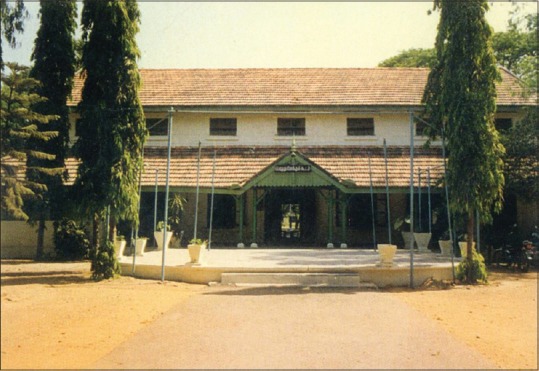

Figure 4.

Institute of Mental Health

Specialized care for specific general medical problems

Scabies was a common prevalent infestation in the hospital. There were no facilities for steam laundry for mats and mattresses and hence cross-infestation and reinfestation were rampant. They were treated with sulfur ointment, Danish ointment, and in later period with benzyl benzoate emulsion, besides adopting other hygienic methods. Another very common affliction was infestation with various worms – roundworms, whipworms, hookworms, and threadworms. Protozoal infections with Entamoeba histolytica were also common. Before the advent of modern drugs, carbon tetrachloride, oleum chena podium, and tetrachloroethylene were the drugs used for deworming.

The “Diarrhea Block”

It was convenient to segregate patients afflicted with nonspecific enteritis and dysentery. Such minor epidemics are not uncommon in closed communities. However, when patients required more energetic and specialized treatment, they were transferred to the infectious diseases hospital, located about 10 km away.

The “Leprosy Block”

A separate ward for male leprosy patients and another for females in female enclosure were maintained. Majority of the cases were of the noninfective neural type with deformities of the hands and feet. Opinion of experts of Government General Hospital was obtained about the noninfective nature of the disease, and they were transferred to other general wards of Mental Hospital.

Repeated attempts were made to transfer them to the Leprosy Sanatorium at Tirumani that is located about 60 km from Chennai. Before the introduction of dapsone, chaulmoogra oil and creosote were given subcutaneously twice a week. The hypopigmented patches were treated with intradermal injections of ethyl ester of chaulmoogra oil, camphor, and Hydnocarpus, known as “ECCO” injections. It is worth mentioning that these procedures were undertaken in the hospital itself by the Deputy Overseer Mr. Viswanathan and Mr. Narayana. Antimony preparations, especially Stibatin, were given intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV) for lepromatous reactions.

The Father of our nation Mahatma Gandhi, during his visit to Tamil Nadu in March 1946, visited the temples at Madurai and Palani. He then passed by Tirumani, when the inmates of Leprosy Sanatorium at Tirumani greeted him. He wrote in his Navajeevan: “I visited the Gods at Madurai and Palani; the Gods visited me at Tirumani.”

The “Tuberculosis Block”

Tuberculosis (TB) infection among the mentally ill is a common phenomenon worldwide, due to various factors. General “Sanatoria’ measures were practiced in the hospital too. Opinion was obtained from TB specialists of Sanatorium at Tambaram located about 15 Km from the city in difficult cases. After the advent of streptomycin in 1944, para-aminosalicylic acid in 1948, and isoniazid in 1951, the “White Plague” lost much of its dread and TB was managed as any other disease.

Care of the Mentally Retarded Children

Among the long-stay patients of the hospital, usually numbering around 1000, about 25% of them belonged to the various categories of mental retardation. The severely retarded (IQ <50) patients formed about 67% and the rest mildly retarded. About half of these patients had epilepsy and other concomitant disorders. Care of these children and adolescents is particularly difficult, many of them requiring “total” care. A “School” opened during Dr. Venkatasubba Rao's time for defective children was functioning regularly in the campus of the hospital.

“Criminal” Ward

In 1954, before States Reorganization on linguistic lines, there were about 170 criminal patients. This part of the hospital [Figure 5] was considered almost an annexe of the Central Prison, Madras, even though manned by the hospital staff. The patients did not have the privileges of their civil counterparts. With a few exceptions, they were not allowed access to other parts of the hospital. It occupied almost a tenth of the hospital area, with a number of airy blocks, single rooms, and cultivable lands to grow good quality of vegetables and fruits that were supplied to the hospital kitchen. A number of sports such as football, ring tennis, and kabaddi and indoor games such as caroms and chess were encouraged.

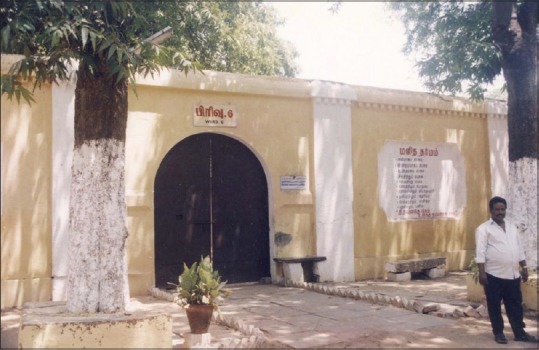

Figure 5.

The “Criminal” ward

These patients were seen once a month by the hospital visitors, and there were two special “Criminal Committees” in the months of June and December, which included a senior representative of Inspector General of Prisons, mostly Superintendent of the Central Jail, Chennai. A patient found “Fit to stand trial” was sent for trial. Similarly, the prisoners serving the sentence were returned to the jail if they had recovered. It could be said that these patients received custodial care par excellence.

“Vigilance” block

Patients who had expressed suicidal intentions by words or deeds and those with suicidal risk were segregated in this ward, which was intensely monitored by the nursing and other staff day and night. During night, one or two recovered patients were also included in the group, who could request help during emergencies.

Psychotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) were the only modes of treatment for these patients until the advent of antidepressants and other drugs. However, also considering other emergencies, an “Intensive Psychiatric Care Unit” was established in 2003 during the tenure of Dr.R. Ponnudurai.

DIL block

Seriously physically ill patients were treated in various parts of the hospital. It was rather inconvenient for the night duty doctor to visit such patients in various wards. Hence, during the tenure of Dr. T. George (1957 to 1961), all such patients were put in this ward where senior nurses and attendants were posted with necessary equipment and resuscitating gadgets. Similar ward was set up for female patients in female enclosure. In the later period, Dr. M. Vaidhyalingam who was also designated as physician of this hospital contributed significantly not only in administration but also in managing the medical problems of the patients until his retirement as superintendent in 1986.

Staff pattern and administrative aspects

When Dr. H. S. Hensman took over as Superintendent in 1924, he and the Deputy Superintendent Dr. Parasuram were the only medical officers with additional training. Later, during the tenure of Dr. A. S. Johnson, 1948–1957, there were 13 medical officers, a few staff nurses, deputy overseers, and attendants. The hospital was divided into 13 sections, 9 for men and 4 for women in female enclosure. To relieve the medical officers from the administrative burden, the government had appointed lay secretaries. The bed strength was officially regularized at 1800. Later during Dr. George's tenure, the services of a psychologist were made available. A trained psychiatric social worker was appointed in 1960.

At the early period of Dr. M. Sarada Menon's tenure, there were 14 medical officers apart from the superintendent, deputy superintendent, and resident medical officer (RMO). Only three of them were trained, but the others by virtue of their experience were able to handle the work well. Office administrative works were done by the Lay Secretary and his team of officials. Nursing staff, overseers, psychologists, social workers, statistician, pharmacists, recreation therapist, occupation therapist, physiotherapist, teacher for children, medical record official, garden supervisor, photographer, dietician, kitchen staff, male attendants (warders), female attendants, and other staff members were also recruited.

The strength of the hospital in 1961 rose to 2800 as against the sanctioned 1800. During this time, “Day-Hospital” arrangement in the outpatient section proved to be very effective in reducing the admissions. That apart encouraging “Temporary Discharges” as per the provisions in Indian Lunacy Act 1912, further paved the way in reducing the inpatient strength.

ADVANCEMENTS IN MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

The period of about six decades from its inception could be referred to as “the period of custodial care” as the primary concern of the authorities was to see that the persons committed to the asylum did not harm themselves, or each other, or escape from the institution to be a source of danger to their fellow citizens. Mechanical restraints such as manacles and chains were in use. The turbulent and aggressive were “isolated” in the single rooms [Figure 6]. Massive iron-barred doors guarded the entrance. There was a single barred ventilator opening just below the ceiling in every room. A mat was provided. A part of the room had to be used as a dry latrine. Much later, in the 1960s, the rooms were provided with cement water closets.

Figure 6.

Single rooms

INTRODUCTION OF ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY AND INSULIN COMA THERAPY

After the invention of physical methods of treatment and introduction of more scientific pharmacotherapeutic agents, management of aggressive and violent patients became easier as it was in other parts of the world. Under the stewardship of Dr. Dhairyam from 1939 to 1948, the patients got the benefits of ECT and insulin coma therapy including modified insulin coma therapy. The time lag in this institution, with regard to the introduction of ECT, has been due to the emergence of World War II on which many changes, long over-due, were kept pending.

Dr. A. S. Johnson who assumed charge of Superintendent in 1948 was a great believer of insulin coma therapy and he adopted it in our institute. IV glucose was used to break the coma which lasted 15 to 20 min – 30 comas, 5 days/week for 6 to 8 weeks. The common untoward reaction was “irreversible” coma which lasted from few hours to 1 to 2 days. There were occasional fatalities. Another insulin treatment, so-called insulin histamine therapy, involved giving small doses of insulin with good doses of histamine. This less hazardous treatment became more popular among medical officers until the regular use of conventional major tranquilizers.

Progress in pharmacotherapy

In the prephenothiazine days, I.V or I. M. barbiturates, parenteral paraldehyde, and opiates were used for sedation. In addition, short-acting barbiturates, chloral hydrate, and paraldehyde and tablets of Rauwolfia serpentina were used for oral medication. However, after the introduction of Chlorpromazine in 1952 and its use 2 years later at our hospital, these drugs were gradually discontinued.

Psychosurgery

Mention has to be made here of Dr. K. C. Nambiar, Surgeon to the Government Stanley Medical College Hospital, who undertook to do psychosurgical procedures for selected patients sent to him. It was claimed to be a partial success during the years 1948 to 1950 as it was said to yield better results in agitated and highly deluded cases. This arrangement continued until Dr. V. Balasubramaniam of the then newly formed Department of Neurosurgery, Madras Medical college, undertook this task. A vivid account of the psychosurgery era of our hospital has been documented by Somasundaram and Balasubramaniam.[1] Furthermore, a follow up of the patients treated with stereotaxic amygdalotomy was undertaken by Ramachandran et al.[2] However, the procedure went out of vogue soon, not due to unequivocal evidence of lack of safety but due to quality of outcome being poor and development of complications.

INTRODUCTION OF GENERAL HOSPITAL PSYCHIATRIC SERVICES AND STARTING OF SPECIAL CLINICS

For the first time in this part of the country, the subject of psychiatry was extended from Mental Hospital to General Hospital Psychiatric Clinics that were opened in the two city Medical College Hospitals – Government General Hospital, by Dr. A. S. Johnson, and at Government Stanley Hospital, by Dr. T. George in 1949 and 1954, respectively, with visiting medical officers from Mental Hospital. Not long after this venture, psychiatry was taken out to the district also when the psychiatric clinic of Madurai Medical College Hospital (Govt. Erskine Hospital) was opened in 1957.

During Dr. M. Sarada Menon's period (1961–1978), several special clinics were started. Child Guidance Clinic started functioning under Dr. O. Somasundaram who got training in child psychiatry at the UK. Other special clinics were neuropsychiatric clinic, geriatric clinic, epilepsy clinic, adolescent clinic, and neurosis clinic.

PROGRESS IN REHABILITATION PROCESS

Recreation therapy

The whole compound was converted into a garden, and some playgrounds were created for the patients to play tennis, volleyball, badminton, tennikoit, etc. Group activities and games were introduced. Dramas were organized in the recreation hall [Figure 7] where both the patients and staff participated. Radio sets were provided in the recreation hall and in some of the wards also.

Figure 7.

Recreation hall

Facility in the recreation hall for worship was provided for patients of all religions. Every year Pongal day celebrations, Christmas day function, etc., were organized.

A bus-cum ambulance was sanctioned by the government that was utilized to take the patients for picnic to places like beach. Every year Sports day was conducted and eminent personalities including hon’ble ministers were invited for distribution of prizes to the patients. Dr. R. Ramadoss, who was also honored with the title of “Mr. Madras,” conducted annual sports event meticulously, until his retirement in 1978. He also conducted yoga classes for the patients.

Occupational therapy

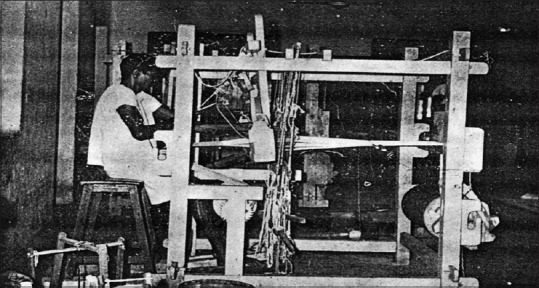

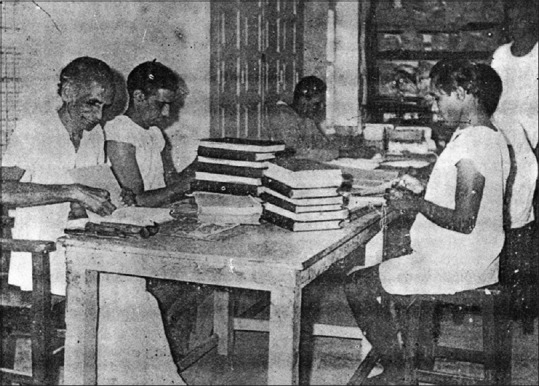

This was introduced as early as 1949. Occupations introduced were gardening, Weaving [Figure 8], tailoring, carpentry, toy making, smithy, embroidery, cotton and coir rope making, mat making [Figure 9], bookbinding [Figure 10], poultry farm, washing clothes, general cleaning of premises, and kitchen works [Figure 11]. Books were bound for other hospitals also. Mats and the like were sent to other hospitals as per demand. About 150 patients were attending this occupation therapy every day. Dr. Rajaiah D. Paul started a guinea pig farm in the criminal ward which was sold to the King Institute, Guindy. He supervised the OT section and gardening too, until his promotion as professor of psychiatry, Coimbatore Medical College in 1977. During this period, Dr. K. Bushanam also did an excellent work in these rehabilitation processes. The items thus made were sold, and the fund was utilized for maintenance of these units including for payment to patients.

Figure 8.

Weaving section

Figure 9.

Block in hospital later used for mat weaving

Figure 10.

Bookbinding section

Figure 11.

Diet cart

Industrial therapy center

In the year 1970, under the supervision of Dr. M. Sarada Menon “Industrial Therapy Centre” was established after obtaining government permission (G.O. No.MS 2634 Health Department dated: 12.11.70) with the help of philanthropists, and, Dr. M. Peter Fernandez was made as medical officer in charge. This was a nonprofitable and therapy-oriented center, primarily focusing on psychosocial rehabilitation. Over the years, the center was developed and has a soft toys manufacturing unit, wire bag unit, agarbatti unit, paper cover making unit, chalk piece making unit, soap preparing section, a flour mill for grinding the essential day to day of the kitchen of IMH, and a candle making section. There is also a bakery unit [Figure 12] that caters to the daily requirement of bread for the Mental Hospital, besides supplying biscuits, cakes, and other confectionaries to the hospital canteen. In later years, for other government hospitals too, bread was supplied from this center, and the expenses were collected from their head of account. A cafeteria is run by this center for the patients and staff of this hospital.

Figure 12.

Bakery unit

The patients who were working were paid a nominal sum of money in appreciation of their work and they were allowed to use that for buying eatables from the hospital canteen. After their discharge from the hospital, placements were also arranged with the help of psychiatric social workers to enable them to earn for their livelihood. They were also permitted to work in this center as outpatients.

TRAINING OF MEDICAL AND PARAMEDICAL PERSONNEL

The Indian Red Cross Society commenced courses for training social workers and Dr. Johnson took on himself the responsibility for introducing these students to psychiatry. It has to be conceded that the course was only for 12 months, but, even so, it was the beginning of bigger changes to take place in the life of the hospital. The undergraduate medical students received instructions for 2 weeks in batches during the final year of their study.

Advancement in professional sphere was witnessed with Dr. M. Sarada Menon at the helm of affairs from 1961. One of the medical officers was asked to be in-charge of medical journals and the collection of reference books on stock, and this was the beginning of the “Medical Library.” Students reading psychology, sociology, and social work at the university level received postings at the Mental Hospital. The medical officers were assigned teaching works also. Dr. S. K. Sivakolundu was in- charge of the clinical society meetings. The hospital which was attached to Madras Medical College later acquired the fame of major teaching institute in the world when the DPM course was started in 1972 and 3 years later MD (PSY) course.

IMPORTANT SCIENTIFIC EVENTS AND BREAKTHROUGH RESEARCHES

The 1957 Annual National Conference of Indian Psychiatric Society was conducted at the campus of our Mental Hospital and the conference was organized under the stewardship of Dr. A. S. Johnson, the then superintendent of the hospital. The president of the society was Dr. G. R. Parasuram,[3] a member of Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh. Dr. T. George was the then secretary and the treasurer of our Indian Psychiatric Society. Dr. Venkoba Rao and Dr. George studied the patients on insulin coma therapy and reported that combining carbutamide with insulin reduced the dose of insulin required to produce coma very considerably.[4]

The diagnosis of General Paralysis of Insane (GPI) was made in this hospital for a very long time and it was not uncommon to see very old patients with the diagnosis of dementia paralytica. The diagnosis was made with the characteristic signs of the disease confirmed by serology of blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). All the cases had the Lange's colloidal curve in the paretic, luetic forms. They were treated with pentavalent and trivalent arsenicals before penicillin era. It was believed in certain quarters that GPI. was not prevalent in this part of the world. To disprove this myth, Dr. R. V. Rajam, the famous venereologist, Government General Hospital, Madras started a collaborative study of this disease with Dr. George, the then Superintendent (1957–1961). Dr. A. Venkoba Rao, who assisted Dr. George in this endeavor, had later reported the clinical findings.[5] The CSF examination, considered a simple procedure, was performed in this hospital itself whenever serology for syphilis were positive. Not only blood and CSF studies were done to confirm the diagnosis, but also some of the patients underwent cerebral biopsy. Cases of syphilis with mental deficiency have also been reported from this institute during this period.[6] A notion in 1970s that Alzheimer's dementia was nonexistent in our country was disproved by Somasundaram,[7] by demonstrating this disease by cerebral biopsy.

CONCLUSION

Disenchanted with the care available in the large institutions with bed strengths 2000 to 5000, and unusual publicity given to the many deficits in care ending in gross violation of human rights, prompted many of the Western countries to downsize these institutions. This deinstitutionalization without the community services rendered many of these ex-patients to homeless wanderers and a sizable portion ended up in prisons. This could serve as a lesson for India where the psychiatric services are still woefully inadequate and hence downsizing of the Indian Mental Hospitals should not even be considered. Recently, it has been reported[8] that of patients admitted in the open wards of an outpatient block of Mental Hospital meant for acute care with family members by their side, even within a week or two, 54.1% males and 35.7% females had to be shifted to the closed main hospital as the relatives expressed their inability to look after them. Needless to say that the State Psychiatric Hospitals play a pivotal role in the Mental Health Care delivery system even in this modern era.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Somasundaram O, Balasubramaniam V. Psychosurgery revisited. Indian J Psychol Med. 2005;26:61–6. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramachandran V, Balasubramaniam V, Kanaka TS. Follow up of patients treated with stereotaxic amygdalotomy. Indian J Psychiatry. 1974;16:299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parasuram GR. Indian psychiatric society presidential address-1957. Indian J Psychiatry. 1958;1:89–91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao V, George T. Some recent trends in insulin therapy of Psychotic patients. Indian J Psychiatry. 1958;1:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Venkoba Rao A. Some observations in the incidence and clinical features of general paralysis of insane. Curr Med Pract. 1958;2:523. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somasundaram O. Syphilis and mental deficiency. Indian J Psychiatry. 1967;9:137–44. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Somasundaram O, Sarada Menon M. Cerebral biopsy in dementia. Indian J Psychiatry. 1975;17:108–17. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponnudurai R. Role of State Institutes of Mental Health – A Preliminary Study from Tamil Nadu. Proceedings of Annual Conference of Indian Psychiatric Society. Tamil Nadu Br. 2008:42–5. [Google Scholar]