INTRODUCTION

Reserpine, an alkaloid derived from the plant Rauwolfia (Sarpagandha), once known for its uses in neuropsychiatric care, is almost forgotten. Following its isolation “in pure crystalline form” from the roots of the Rauwolfia plant in 1952 by Műller, Schlittler, and Bein, under the Aegis of the Swiss Pharmaceutical Companies CIBA and Geigy, the alkaloid became commercially available in the first world as “Sarpasil.”[1] The Swiss companies’ emerging interest in the drug market of post-war US had already resulted in their dissolution of the cartel, Basel AG, in 1951 to comply with the American Antitrust Law, which significantly increased their trade in the US. Reserpine therapy also got a place in the US shortly after “Sarpasil” was marketed, when Dr. Robert Wilkins from the Boson University School of Medicine formally confirmed its sedative and antihypertensive properties as early as 1954.[2] Nathan S Kline, the noted American psychiatrist, was the first to formally establish Sarpasil's efficacy in psychosis in large doses at the Rockland State Hospital.[3] Robert H Noce, Director of the Clinical Services at the Modesto State Hospital, California, conducted trials of Sarpasil on refractory cases of schizophrenia and on the mentally retarded as well, which facilitated integration of “psychiatric problems of mental deficiency with those of general psychiatry.”[4] The 1957 Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award[5] went to Nathan Kline and Robert Noce, along with Pierre Deniker, Heinz Lehmann, and Henri Laborit for their discovery of the clinical efficacy of reserpine, and chlorpromazine, on the mentally ill. This radically transformed treatments in psychiatry, which had until then been largely custodial and institution based. The Lasker Foundation also awarded the physician from Bombay, Rustom Jal Vakil, with the same award that year for his “historical paper on the use of Rauwolfia in hypertension which appeared in the British Heart Journal in 1949,” where “he summed up 10 years of careful conscientious work that he had carried out personally, added the opinions of some 50 other physicians who had worked with Rauwolfia in hypertension, and produced a document which brought this drug finally and decisively into Western medicine.”[6] The Foundation commented in the same note that “The story of Rauwolfia serpentina is an example of a block in medical communication that, in retrospect, seems hard to understand,”[7] as its therapeutic uses, though well known in south Asia, were unknown in the first world still then.[8]

While this “block in medical communication” apparently left the American Foundation bewildered, the frustration and agony of the first world scientism did not remain suppressed in the comment, which at the same time tried to put the whole practice of Indian medicine under the trope of “traditional medicine.” This article problematizes the modern scientific discovery of reserpine by juxtaposing it with earlier aims to isolate and standardize the alkaloid by the Indian physicians and scientists in the early twentieth century south Asia. The article challenges any notion of singular insularity of “traditional” and “modern” medical spaces and finds these categorizations to wield as tools of appropriation of peripheral practices into the commodified superiority of western knowledge.

SARPAGANDHA IN SOUTH ASIA

One of the drugs identified in the Indian medical lore for treating insanity was Sarpagandha (Rauwolfia serpentina), also known as Chota-Chand (Hindi), Chandra (Bengali), Pa’tala-Gandhi (Telugu), Chuvanna-avilpori (Malayalam), Convannamilpori (Tamil), Chandrika, and few other similar names in some Indian languages (all implying link to Chandra [the “moon”], perhaps referring to the association between the moon and madness). This long-known Indian plant Sarpagandha took the attention of Rumpf, a botanist with the Dutch East India Company in 1755. The genus was named Rauwolfia by Linnaeus, in honor of Leonhard Rauwolf, a German botanist who had travelled to the Middle East and documented several medicinal plants there. Rumpf was made aware of the use of the drug in south Asia for treatment of insanity, which he recorded.[9]

Some scholars have referred to Sarpagandha as an Ayurvedic drug, which does not seem entirely appropriate. Dr. Kartick Chandra Bose wrote in 1932, “the drug is not considered officinal to the Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia – at least it has not been clearly identified as such. The names ‘Chadrika’ and ‘Sarpa-gandha’ quoted by some authors as the Ayurvedic names for it are misnomers. No drug named as above and having similar properties as Rauwolfia can be found in any of the ‘Nighantus’ of Ayurvedic literature.”[10] The dried roots of Sarpagandha, however, were known “as a febrifuge, and as an antidote to bites of poisonous reptiles, also in dysentery and other painful affections of the intestinal canal.”[11] Indian physicians in the early twentieth century carried out extensive empirical research on the physiological and pharmacological properties of Sarpagandha and carefully noted them. It was chiefly popular, however, for its use in treating mental afflictions as was noted in Bose's Pharmacopoeia Indica. “All the indigenous secret of patent remedies that are sold for insanity and mostly made up of Rauwolfia serpentine – and its principal use all over the country – is in cases of insanity”.[12] Extracts from the roots of Sarpagandha were indeed easily available at village markets all over India at remarkably cheap prices, as pagalon ki dawa, meaning “drugs for the mad,” until the mid-twentieth century.[13] It was also commonly used by mothers in many parts of eastern India in small dosages to put their crying babies to sleep.[14] The powdered roots of Sarpagandha was also used by other noted medical practitioners, such as the legendary North Indian physician Hakim Ajmal Khan and Bengali physicians Kartick Chandra Bose and Gananath Sen, to treat mental disorders.[15]

SCIENTIFIC ADVANCEMENTS IN SARPAGANDHA RESEARCH: INITIAL YEARS

Plural medical markets, beyond (colonial) government pharmacies, were available in the subcontinent for a long time. They used to sell a great variety of locally available drugs, and from the later decades of the nineteenth century, a pragmatic interest in those locally available medicines increased mainly through international drug exhibitions held in Calcutta and other parts of the subcontinent.[16] By the early twentieth century, the already grown involvement of the Indians in modern science and small entrepreneurial activities gained impetus from the Swadeshi movement and made complex transformations in that plural medical market. The early twentieth century efforts of standardization of the pharmacological properties of Sarpagandha, in India, along the lines of western techno-empiricism, could be contextualized in that space.

Professor Salimuzzaman Siddiqui,[17] the noted scientist at the Tibia College in Delhi, undertook systematic research of the active constituents of Sarpagandha roots and root bark, after his return to the country from Germany in 1927. The Tibia College in Delhi was established under the aegis of the legendary physician and Muslim nationalist Hakim Ajmal Khan, as an autonomous medical teaching and research institution beyond the colonial establishment of the British. Dr. Kartick Chandra Bose and Gananath Sen, two leading physicians from Calcutta, by that time, independently, reported on the use of an alkaloid extract from Rauwolfia in hypertension and “insanity with violent maniacal symptoms.”[18] While Sen came from the tradition of Ayurvedic medicine, Bose was a graduate of the Calcutta Medical College. Almost immediately Siddiqui, along with Hussein, then at Aligarh Muslim University, isolated several compounds from the roots of Sarpagandha,[19] many of which are still being used worldwide. R. N. Chopra, the father of Indian Pharmacology, Rustom Jal Vakil, the physician who popularized the use of Rauwolfia in hypertension, and many others extensively quoted Siddiqui in their subsequent research.[20] Siddiqui had discovered what later became known as a remarkable anti-arrhythmic agent of class Ia,[21] which is still a first-line agent in the treatment of ventricular tachyarrhythmia. Its pro-arrhythmic potential is also used to bring out the typical findings of ST elevation in the ECG, in patients suspected of having Brugada syndrome.[22]

Siddiqui succeeded in extracting at least nine distinct alkaloids from Sarpagandha roots from different parts of the Indian subcontinent.[23] Sharing the larger nationalistic vision of south Asian polity, Siddiqui named the anti-arrhythmic agent “ajmaline,” after Ajmal Khan, from whom Siddiqui had come to know about it.[24] He named some other Sarpagandha alkaloids after Ajmal Khan as well namely, ajmaline, ajmalicine, isoajmaline, and neoajmaline. Siddiqui's subsequent research was on isolating medicinal compounds from Neem and Holarrhena. Professor Siddiqui's contributions in pharmaceutical chemistry at the Hamdard Foundation were not unusual. It fitted well within the then established trend of composite scientific discoveries and entrepreneurial activities adopted by other Indian intelligentsia and small bourgeois, most notably, similar pharmaceutical preparations discovered and marketed in Calcutta by Professor A P C Ray (at the Bengal Chemical & Pharmaceutical Ltd.) and Dr. K C Bose (both at the Bengal Chemical and at the Bose Laboratories) beginning from the preceding decades. However, all of these were always small to medium-scale entrepreneurial activities, often erected as parallel or counter establishments to the colonial government, with strong nationalistic sentiments and worked on progressive political and social ideologies. In contrast, the Geigy and CIBA in the Basel began their journey as big dye industries in the mid-nineteenth century to control the dye trade in entire Europe for nearly a century and came to the drug industry following the discovery of Di-chloro di-phenyl tri-chloro-ethane (DDT) and other drugs during the Second World War.[25] Such large-scale global business, conducted by companies of a metropolitan country, were not even conceivable by the progressive local bourgeois of the colonized south Asia, which lacked the logistic infrastructure required to make techno-scientific advancements. No wonder, as this paper goes on exploring in the subsequent sections, the isolation of the specific alkaloid responsible for the sedative properties of Rauwolfia eluded the Indian researchers.

VALIDATING SARPAGANDHA IN MENTAL AFFLICTIONS

Bose and Sen were also collaborating with the Chopra group from an earlier period at the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine to work on Sarpagandha. In their 1931 article titled “Rauwolfia serpentine, a New Indian Drug for Insanity and Blood Pressure,” Bose and Sen explained that “doses of 20 to 30 grains of powder twice daily produce not only hypnotic effect but also a reduction of blood pressure and violent symptoms.”[18] Bose and Sen carried out careful observations on the efficacy of Sarpagandha, and Bose documented all those minute details in his Pharmacopoeia Indica (1932), to call for other researchers’ notice. He wrote, “As this drug is one of the rare merits, further investigation and researches on the Chemical Composition, Physiological Action, and Therapeutic uses are needed and we invite the research workers’ attention to this active medicament.”[26] Subsequently, the research team led by Sir R. N. Chopra in the Chemistry Department of the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine (CSTM) began research on Rauwolfia and its alkaloids, and they published their findings in 1933, confirming that Rauwolfia had the potential to reduce blood pressure.[27] However, although they also “demonstrated that crude extracts of the root had powerful sedative properties,” they were unable “to isolate an alkaloid with sedative activity.”[28] Professor Bishnupada Mukerjee (1903–1979), Padma Shri (1962), the noted Indian pharmacologist who was associated with Chopra's Calcutta group, later lamented over their practice of discarding the “oleoresin” fraction of Sarpagandha assuming it free from alkaloid extract, while the sedative properties of Sarpagandha were actually concentrated within that “oleoresin” fraction.[29] Professor Mukerjee further suggested, “…observation of the workers of the Calcutta School of Tropical Medicine (CSTM) were duly utilised by Műller, Schlittler, and Bein (1952), in working out a special method of isolation of the weakly basic Rauwolfia alkaloid, reserpine. It was shown that the typical pharmacological properties of Rauwolfia, as observed in the ‘oleoresin’ by workers at the CSTM, were due to reserpine. This weakly basic crucial alkaloid eluded the workers at CSTM in view of its insolubility in dilute acids, which was mostly used in those days in the poorly funded laboratories of the colonial tropics, for extraction of alkaloids from neutral products as in the total plant extract.”[30]

However, though the lack of logistic support was a hindrance, with the support of Bose and Sen, Chopra et al. worked out the safe dosage for human administration and started trialing the drug on their patients at the associated Carmichael Hospital for Tropical Diseases. Noting the sedative action as quite remarkable, the team at the CSTM thought of a controlled trial for the drug involving the Indian Mental Hospital in Ranchi (now RINPAS).[31] Alcoholic extracts of Sarpagandha were sent to Ranchi for the first time in 1935 with a request to “try this medicine as it is renowned as a specific for insanity.”[32] Superintendent Dr. Dhunjibhoy was then in his fourth extended visit in Europe, and his locum, Dr. Pacheco, administered the drug “both orally and by injections” to 26 male and 14 female patients suffering from acute excitement (diagnosed with mania or catatonia). Pacheco concluded that “as a hypnotic,” the drug was “very efficacious specially in allying restlessness of excited patients.”[33] Another fresh batch of the drug arrived Ranchi in 1936, by which time Dhunjibhoy had returned from Europe. He, however, reported that the trials were “disappointing.”[34] Waltraud Ernst, the noted historian of psychiatry in south Asia, suggests that the contradictory reports of Dhunjibhoy and Pacheco might have been a consequence of the different batches of drugs they received. It is also possible that the Europhile Dhunjibhoy was more motivated to offer world-class modern amenities in Ranchi, based on western principles rather than finding substances from an indigenous drug.[35] Records show that Dhunjibhoy experimented with western drugs on his patients with great enthusiasm as soon as there were published reports on successful trials of those drugs in scientific literature.[36] In 1933, along with sweet basil, he experimented with nembutal, soneryl, somnifene, and hypnol; of these nembutal and soneryl are barbiturates, synthesized for the first time in 1930 and 1921, respectively. None of these drugs actually were proved to be of help to mentally ill patients in the long run. Rohypnol, a modified version of soneryl and hypnol, has recently received attention as a date-rape drug; nembutal, also known as a recreational drug, is now administered in doctor-assisted suicides and capital punishment in some countries; while interest in somnifene waned after the 1930s. Dhunjibhoy however found all of them “useful” though only “in some cases of excitement and insomnia” yet believed them to be “worth trying [when] other ordinary drugs fail […] in highly refractory cases.”[37] As Ernst notes, “this had been and continued to be a standard phrase in the annual reports.”[38] Dhunjibhoy's reliance on bromides, barbiturates, and amphetamines was great, even when he himself did not get any conclusive result from trials on his patients, while the reverse was the case with trials of Sarpagandha. Ernst aptly suggests, “It is tempting though to postulate that Dhunjibhoy, the Parsi from India, may have in his ambition to emulate modern, cutting-edge treatments, been blinkered regarding the potential of drugs commonly used by indigenous practitioners and folk healers.”[39] Chopra too discouraged publication of inconclusive data of human trials of Sarpagandha, while being well aware of the fact that data from private practice and outside clinics unequivocally recommended the use of Sarpagandha in mental afflictions.[40] Ironically, Chopra himself headed the Indigenous Drug Committee for decades, and his own reports of 1933 and 1947, much like his western predecessors in the prestigious and authoritative Indian Medical Service (IMS), failed to assess indigenous medicines beyond sympathy.[16] Contrary to Chopra and Dhunjibhoy, the works of Bose, Sen, and Siddiqui, none of whom were doctors from the IMS, appear to be more empirical, and in essence, without specific pre-determined assumptions, which tried to evaluate the efficacy of certain indigenous medicaments without hesitation.

THE LOST OPPORTUNITIES IN PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY RESEARCH IN SOUTH ASIA

Rustom Jal Vakil started his research on the effects of Rauwolfia by the late 1930s, and his paper in 1949 on Sarpagandha's pharmacological properties, especially in reducing blood pressure, familiarized the western world with Sarpagandha and earned Vakil worldwide fame.[41] During the 1950s, reserpine was successfully applied in psychoses in the west and is still in use in select cases of refractory schizophrenia and Huntington's disease. Vakil was made a Fellow of the Royal Society, but the use of reserpine to treat mental illness receded to the background in India.

Professor Salimuzzaman Siddiqui, Gananath Sen, and Kartick Chandra Bose are now relatively forgotten names in the history of the psychopharmacology of reserpine, in particular, and antipsychotic treatments, in general. If we look at Prof. Siddiqui's career, he became Director of the newly established Indian Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (ICSIR) in the 1940s.[42] There, on request from Sir Shanti Saroop, Bhatnagar, he introduced election ink to ensure fair electoral practices but ironically had to spend the latter half of his life in a country that seldom had use of it.[43] However, the same formula is still being used in every election in India. After Partition, Dr. Siddiqui moved to Pakistan.[44] Heading the Pakistan CSIR since 1951, Siddiqui greatly influenced scientific development in Pakistan.[45] There are two different accounts of Dr. Siddiqui's moving to Pakistan. One is that he moved to Pakistan as the result of a personal request from Liaquat Ali Khan to Jawaharlal Nehru, who made his services available to Pakistan to develop its scientific base.[46] Contrary to this, there is very strong suggestion that Dr. Siddiqui had no other option but to move to Pakistan, due to the strong anti-Muslim milieu in Delhi on the eve of Partition, which got coupled with institutional and sectarian politics, making his position at the ICSIR and India a bit uncertain.[47] His brother Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman (who had been a prominent politician and a member of the Constituent Assembly) had already left for Pakistan in 1947. During the riots that followed Partition, Dr. Siddiqui was being regularly escorted to his residence by his Hindu pupils and sometimes had to take refuge in Muslim cabinet ministers’ homes, as they had police protection.[48] However, Prof. Siddiqui continued to have a family in India, became a member of the Royal Society, and was one of the founder members of the Third World Academy of Sciences at Trieste,[49] along with M. G. K. Menon (the noted theoretical physicist from India born in 1928) and Abdus Salam (the 1979 Nobel Prize-winning physicist from south Asia; 1926–1996). His elder brother, Chaudhry Khaliquzzaman also became a pariah both in Pakistan and in India, after he lamented the “two-nation theory” as a retrogressive move for the subcontinent in his autobiography “Pathways to Pakistan” (1961). Interestingly, and regretfully, Indian scientific history is meaningfully silent regarding Siddiqui, while from accounts in the Pakistani journals, it would even be very difficult to conclude whether he lived in India at all![50]

Similarly, Gananath Sen and Kartick Chandra Bose are relatively forgotten names in the history of psychopharmacology in India. Their remarkable efforts in standardizing the pharmacological properties of Sarpagandha research, which later made Vakil famous, earned Bein and Woodward a Nobel Prize in 1965 (for unraveling the structure of reserpine, an effort started by Sen, Bose, and Siddiqui), and again earned Arvid Carlsson one in 2000 (for understanding the biology of reserpine and demonstrating the reversal of its effects by L-DOPA). Bose and Sen were thus men ahead of their time, who sent alcoholic extracts of Sarpagandha to Ranchi some 20 years earlier, for systematic trials.

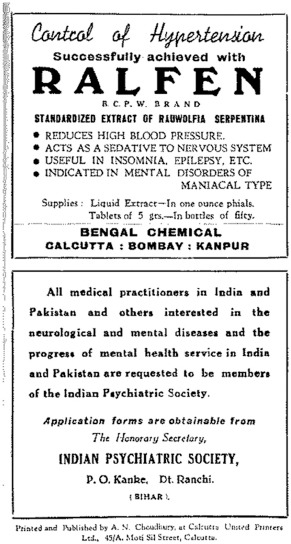

Interestingly, and most tellingly, the age of Bose and Sen witnessed arrival of several treatment modalities in psychiatry, such as malaria therapy (1918), psychoanalysis (the 1920s), insulin coma (1933), metrazol therapy (1937), and leukotomy (1939), none of which actually withstood the test of time, despite Wagner-Juaregg's Nobel Prize in 1927 for malaria fever therapy. All of these western treatment modalities were readily adopted into practice with great enthusiasm, almost as soon as they were launched in the west, in the then apex mental hospitals of India run by the Indians, namely in the Mental Hospital of Bangalore (which later became the All India Institute of Mental Health in 1954 and since 1974 is known as NIMHANS) and in the Indian Mental Hospital at Ranchi (now RINPAS). Sarpagandha were being used in the Mental Hospital of Bangalore, but no systematic research or trial was conducted to establish its efficacy. Govindaswamy's[51] preoccupation with leukotomy, convulsive therapy, and psychology, and Dhunjibhoy's pursuit for offering world class modern amenities in Ranchi, with his increasing reliance on “barbiturates (sedatives, hypnotics, and antiepileptics)” as Ernst suggests, might have perhaps been the reason for the neglect of trials of an indigenous drug, the “western scientific discovery” that India missed, and the West caught, and extended, some 20 years later. It is to be noted though, that ironically, by 1949, the extract of the Rauwolfia serpentine became widely available to treat hypertension and “mental disorders of the maniacal type” and was advertised as such even in this Journal (Indian J Psychiatry 1 (2), 1949, p96 carries an advertisement for Ralfen manufactured by the Bengal Chemicals, an image of that advisement is on the right). The extracts were also used widely in India, as a tea (Mahatma Gandhi was a regular user), in hospitals, and more recently both as a slimming agent, as well as a part of traditional medicines!

AFTERWORD

Contemporary intellectuals have tried to locate Bose and Sen strictly within the Ayurvedic revival movement. The article emphasizes the need to look beyond any such tropes. Sen and Ajmal Khan were at the same time patrons and products of Indian Nationalism. Their achievements and limitations too were part of the complex interactions between the colonizers and the educated elite of south Asia. Siddiqui, on the other hand, being born and brought up in Lucknow and Aligarh, associated with the Bengal School of Art in Shantiniketan, living in London, Frankfurt, Delhi, and Karachi, and arranging exhibitions from Berlin to Bangalore, was among those progressive internationalist-nationalists of south Asia, who refrained himself from delving into the complex identity politics of that day (the roots of identity-based sectarian politics in contemporary India has historically been traced into the days of colonialism; those were the formative years of the Hindu Mahasabha, the Muslim League, and the Indian National Congress; ironically and meaningfully, Ajmal Khan was President of all three!) (Metcalf, 1985). Kartick Chandra Bose, in an entirely different way, living with great empathy and activity amidst the plebeians, not deviating from his endless pursuit of empirical knowledge, taking a series of novel measures in Swadeshi entrepreneurship and public health,[52] and most importantly serving for his uprooted, migrant fraternities in the post-partition period, has left some indelible impression in the history of south Asia.

Both Dr. Bose's and Prof Siddiqui's careers highlight the complexities of science and society in the twentieth-century south Asia. At that time, the principles of synaptic biology and pharmacodynamics were not amenable to further understanding as methods to study them were still being developed. Intense research and debates regarding patterns and types of neural transmission and synapses started to emerge as a hallmark of neurophysiology research in the western world by the 1930s.[53] Bose, Siddiqui, and their colleagues, working in their own local laboratories in the peripheral tropics, without access to advanced technologies, and without any commercial incentives from big pharmaceutical business groups, applied their wisdom and skill with all possible sincerity, to set a trend of scientific pursuit linked to socio-political ideologies that could be local enough to deconstruct the western scientism. It is beyond the scope of this paper to track those trends into oblivion following the events of Partition and Decolonization. The appropriation of the practical uses of “do paisa ki pagalon ki dawa” into the western scientific discovery of reserpine, which, like many such similar appropriations, reinforced the tropes of the established discipline of “traditional Indian medicine,” remained and still is an untold tale that this paper has tried to contextualize.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by the Wellcome Trust (London) (Turning the Pages; Grant No. WT096493MA).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

I am indebted to Professor Sanjeev Jain, my principal work supervisor for his constant support, guidance and encouragement while writing this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trade Name of Reserpine, First Marketed by CIBA [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilkins RW. Clinical usage of Rauwolfia Alkaloids, including reserpine (Sarpasil)’ in the ‘Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences’? New Engal J Med. 1954;59:36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1954.tb45916.x. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1954.tb45916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Now Rockland Psychiatric Centre [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mentioned by the Lasker Foundation. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.laskerfoundation.org/awards/show/chlorpromazine-for-treatingschizophrenia/

- 5.The Lasker Award is often Regarded as America's Nobel 20 Prize [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mentioned by the Lasker Foundation. [Last accessed on 2017 Dec 20]. Available from: http://www.laskerfoundation.org/awards/show/treatment-of-hypertension/

- 7.Ibid [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibid [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somers K. Notes on Rauwolfia and ancient medical writings of India. Med Hist. 1958;2:87–91. doi: 10.1017/s0025727300023498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bose KC. Calcutta: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh; 1932. Pharmacopoeia Indica: Being a Collection of Vegetable Mineral and Animal Drugs in Common use in India; p. 153. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ibid. :154. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibid. :154. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanjeev J, Murthy P. The other Bose: An account of missed opportunities in the history of neurobiology in India. Curr Sci. 2009;97:266–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waltraud E. UK: Anthem Press; 2013. Colonialism and Transnational Psychiatry: The Development of an Indian Mental Hospital in British India, c.1925–1940. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abdul M. Karachi: University of Karachi; Studies in the Chemical Constituents of Rauwolfia Vomitoria Afzuelia. PhD Dissertation. August, 1977; Suhail Y. Salimuzzman Siddiqui – A Visionary of Science. Dawn; October, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.David A. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. The New Cambridge History of India: Science Technology and Medicine in Colonial India. Part 3; pp. 176–85. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pradipto R. Salimuzzaman Siddiqui. Hektoen Int J Hektoen Inst Med (Chicago) 2015;7:ISSN2155–3017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gananath S, Chandra Bose K. Rauwolfia serpentina: A new Indian drug for insanity and high blood pressure. Indian Med World. 1931;11:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salimuzzaman S, Siddiqui RH. The alkaloids of Rauwolfia serpentina Benth, Part I, Ajmaline series. J Indian Chem Soc. 1932;9:539–44. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ram Nath C, Gupta JC, Mukherjee B. The pharmacological action of an alkaloid obtained from Rauwolfia serpentina Benth: A preliminary note. Indian J Med Res. 1933;21:261–71. [Google Scholar]

- 21.It works by blocking the sodium and HERG potassium channels in the cardiac myocytes, and thereby prolonging the action potential [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brugada syndrome is a genetic disorder in sodium channels of the heart muscles, which is prevalent in Thailand and Laos, causing sudden unexplained death syndromes resulting from ventricular fibrillation [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salimuzzaman S, Siddiqui RH. The alkaloids of Rauwolfia serpentin a Benth. II. Studies in the Ajmaline series. J Indian Chem Soc. 1935;12:37–47. Salimuzzaman S, Siddiqui RH A note on the alkaloids of Rauwolfia serpentina Benth J Indian Chem Soc 1939;16:421. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdul M. Karachi: University of Karachi, August; 1977. Studies in the Chemical Constituents of Rauwolfia vomitoria Afzuelia. PhD Dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul E. The Basle Marriage: History of the Ciba-Geigy Merger. Zurich, Switzerland: Neue Zurcher Zeitung; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bose KC. Calcutta: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh; 1932. Pharmacopoeia Indica: Being a Collection of Vegetable Mineral and Animal Drugs in Common use in India; p. 155. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chopra RN, Gupta JC, Mukherjee B. The pharmacological action of an alkaloid obtained from Rauwolfia serpentina benth. Indian J Med Res. 1933;21:261–71. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibid [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bisnupada M. Dhanwantari Prize Memorial Lecture. Calcutta: The Asiatic Society; 1 January; 1976. India's Wonder Drug Plant: Rauwolfia serpentina Birth of a New Drug from an Old Indian Medicinal Plant. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ibid [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibid [Google Scholar]

- 32.Triennial Report of the Indian Mental Hospital. London, Ranchi: The British Library; 1933-35. p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibid [Google Scholar]

- 34.Annual Report of the Indian Mental Hospital. London, Ranchi: The British Library. 1936:11. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waltraud E. UK: Anthem Press; 2013. Colonialism and Transnational Psychiatry: The Development of an Indian Mental Hospital in British India, c. 1925–1940; pp. 175–8. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Annual and Triennial Reports of the Indian Mental Hospital. London, Ranchi: The British Library; 1925-40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhunjibhoy JE. Correspondence. J Ment Sci. 1931;77:294–7. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waltraud E. UK: Anthem Press; 2013. Colonialism and Transnational Psychiatry: The Development of an Indian Mental Hospital in British India, c.1925–1940; p. 178. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ibid. :177. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bisnupada M. India's Wonder Drug Plant: Rauwolfia serpentina Birth of a New Drug from an Old Indian Medicinal Plant. Dhanwantari Prize Memorial Lecture 1 January. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta SP. Rustom Jal Vakil (1911-1974) – Father of modern cardiology: A profile. J Indian Acad Clin Med. 2002;3:100–4. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akhtar M. Salimuzzaman Siddiqui, M.B.E.: 19 October 1897-14 April 1994. Biogr Mem Fellows R Soc. 1996;42:401–17. doi: 10.1098/rsbm.1996.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Democracy in Pakistan being Unstable, Voting is not a Regular Phenomenon there. The Country has Experienced Several Decades Under Totalitarian Military Regime (1958 – 1971, 1977 – 1988, 1999 – 2008), When no Election was Allowed to be Conducted [Google Scholar]

- 44.Siddiqui Established the Pakistan Academy of Sciences as a Think Tank of Distinguished Scientists of the Country. In 1956 he was Designated as a Member of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC). Prof. Siddiqui continued to have an interest in chemical technologies ranging from coal processing to extracting medicinal substances from plants. In 1967, he set up at Karachi University the Department of Postgraduate Institute of Chemistry, which became a centre for international excellence. Later on, it came to be known as ‘Hussain Ebrahim Jamal Research Institute of Chemistry’; Siddiqui also headed the ‘National Commission for Indigenous Medicine’ of Pakistan. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ismail SM. Salimuzzaman Siddiqui. Pakistan Association of Scientists & Scientific Professions (PASSP) 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Life sketch of professor Salimuzzaman Siddiqui, F.R.S. J Chem Soc Pak. 1982;4:ISSN2155-3017. Suhail Y. Salimuzzman Siddiqui – A visionary of science. Dawn; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robert SA. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2010. Nucleus and Nation: Scientists, International Networks and Power in India. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ibid [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daniel S. TWAS at 20: A History of the Third World Academy of Sciences. World Scientific; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pradipto R. Salimuzzaman Siddiqui. Hektoen Int J Hektoen Inst Med (Chicago) 2015;7:ISSN2155–3017. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Govindaswamy MV. Was the Superintendent of Mental Hospital, Bangalore (now NIMHANS) and the Founder-Director of All India Institute of Mental Health (1954-59) (now NIMHANS) He obtained his MBBS from Mysore Medical College and DPM from England He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine, and was also the member of Indian Medical Association and World Mental Health Federation Govindaswamy is the man who first brought the psychological, medical, psychiatric and nursing aspects within the hospital framework He advocated application of classical Indian philosophical doctrines to understand personality deviations, and was a key proponent of brain surgeries and other advanced modalities. 1904-62 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bose Established the First TB Sanatorium of India in Deogarh [Google Scholar]

- 53.Greengard P. The Nobel laureate of Physiolgy or Medicine, along with Arvid Carlson and Eric Kandel, refers in his Nobel lecture, to that preceding milieu, as a key factor to channelise his interests in signal transduction and neural pathways. 2000 [Google Scholar]