Abstract

B cell leukemia/lymphoma 3 (Bcl3) plays a pivotal role in immune homeostasis, cellular proliferation, and cell survival, as a co-activator or co-repressor of transcription of the NF-κB family. Recently, it was reported that Bcl3 positively regulates pluripotency genes, including Oct4, in mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). However, the role of Bcl3 in the maintenance of pluripotency and self-renewal activity is not fully established. Here, we report the dynamic regulation of the proliferation, pluripotency, and self-renewal of mESCs by Bcl3 via an influence on Nanog transcriptional activity. Bcl3 expression is predominantly observed in immature mESCs, but significantly decreased during cell differentiation by LIF depletion and in mESC-derived EBs. Importantly, the knockdown of Bcl3 resulted in the loss of self-renewal ability and decreased cell proliferation. Similarly, the ectopic expression of Bcl3 also resulted in a significant reduction of proliferation, and the self-renewal of mESCs was demonstrated by alkaline phosphatase staining and clonogenic single cell-derived colony assay. We further examined that Bcl3-mediated regulation of Nanog transcriptional activity in mESCs, which indicated that Bcl3 acts as a transcriptional repressor of Nanog expression in mESCs. In conclusion, we demonstrated that a sufficient concentration of Bcl3 in mESCs plays a critical role in the maintenance of pluripotency and the self-renewal of mESCs via the regulation of Nanog transcriptional activity.

Keywords: Bcl3, Mouse embryonic stem cell, Nanog, Self-renewal

INTRODUCTION

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) possess the abilities of self-renewal and pluripotency, and can differentiate into three germ layers (1). The pluripotency of ESCs is maintained by core regulatory factors, including Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog (2). Nanog is a critical transcription factor for maintenance of ESCs and regulation of the transcriptional network in the undifferentiated state (3–5). Nanog is required to establish ESC ground state pluripotency and plays an essential role in early embryonic development; Nanog-null ESCs are prone to loss of self-renewal and experience multilineage differentiation (6). In ESCs, Nanog is constitutively expressed by core regulatory factors, such as Oct4, Sox2, and Esrrb, which bind to the promoter region of Nanog (7–9).

B cell leukemia/lymphoma 3 (Bcl3) was found to be overexpressed in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (10). Furthermore, the overexpression of Bcl3 is associated with several cancers, such as classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and solid tumors (11). Bcl3 is classified as a member of the IκB family, containing seven ankyrin repeat domains that interact with homodimers of NF-κB p50 or p52 (12, 13). Bcl3 has been reported to act as a co-activator of transcription that interacts with the mitogenic transcription factor AP-1 (14) and retinoid X receptor (15). Bcl3 is also a negative regulator of TORC3-mediated transcription from the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 LTR (16). Although Bcl3 appears to function as a transcription co-regulator in hematopoietic and solid tumors, its role in other cells, including ESCs, is largely unknown. It was recently reported that ectopic Bcl3 expression positively regulated mouse ESC (mESC) pluripotency and promoted Oct4 promoter activities, whereas silencing of Bcl3 downregulates the expression of self-renewal-related gene expression patterns and facilitates cell differentiation (17). However, the precise contribution of Bcl3 to the maintenance of pluripotency and self-renewal activity has not been clarified.

Here, we investigated whether the gain of function or loss of function of Bcl3 expression might influence the maintenance of pluripotency and self-renewal activity in mESCs. Unexpectedly, excessive or insufficient concentration resulted in a similar suppression of pluripotency, self-renewal activity, and cell proliferation of mESCs by acting as a negative regulator of Nanog transcription in mESCs, which suggested that a precise concentration of Bcl3 might be critical for the proliferation and self-renewal of mESCs.

RESULTS

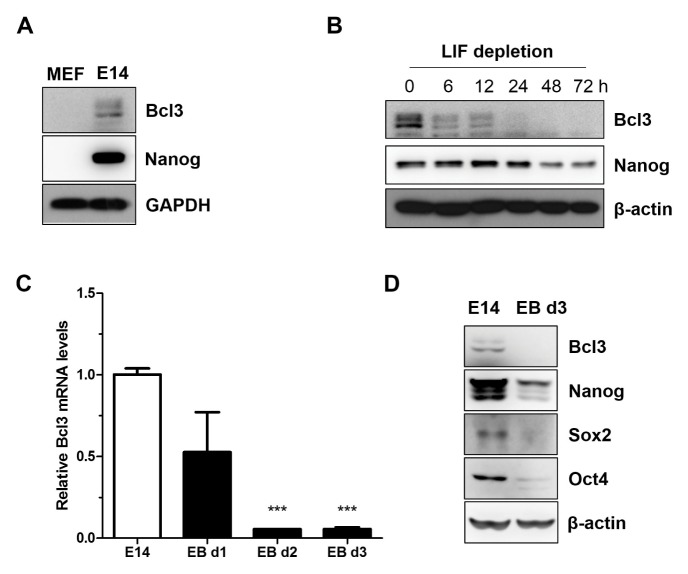

Bcl3 is highly expressed in mouse embryonic stem cells

To determine the role of Bcl3 in mESCs, we first measured Bcl3 protein levels in mESCs (E14 cells) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF). As shown in Fig. 1A, protein levels of Bcl3 were significantly higher in E14 compared with MEF, which suggested that Bcl3 was highly expressed in undifferentiated mESCs. To investigate the expression profile of Bcl3 at the differentiation stage, we performed LIF depletion or incubated cells with low concentrations of serum to form ESC-derived embryoid bodies. In LIF-deficient conditions, the expression of Bcl3 was rapidly decreased in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B), which was also previously reported to occur in the Nanog protein level. Furthermore, compared with undifferentiated mESCs, levels of the Bcl3 transcript (Fig. 1C) and protein (Fig. 1D) were decreased in mESC-derived EBs on days 1–3. Likewise, core regulatory factors, such as Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2, were significantly decreased in mESC-derived EBs compared with E14. These results supported our hypothesis that Bcl3 is important for self-renewal or differentiation of mESCs.

Fig. 1.

Bcl3 is highly expressed in mouse embryonic stem cells. (A) Western blotting analysis of Bcl3 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and E14tg2a cells (E14). GAPDH was used as an internal control. (B) Western blot analysis of Bcl3 in E14 under the leukemia inhibitor factor (LIF) depletion conditions. After seeding, the cells were cultured for 3 days, and then were transferred in LIF depletion media. The samples were extracted at the indicated times. β-actin was used as an internal control. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR assay of Bcl3 in ESC-derived embryoid bodies. Embryoid bodies were formed by hanging drop culture methods and extracted at the indicated times. Data are normalized to β-actin and shown relative to E14 cells. ***P < 0.005 vs E14 cells. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 3). P values were calculated by using one-way ANOVA. (D) Western blot analysis of Bcl3, Nanog, Sox2, and Oct4 in ESC-derived embryoid bodies. β-actin was used as an internal control.

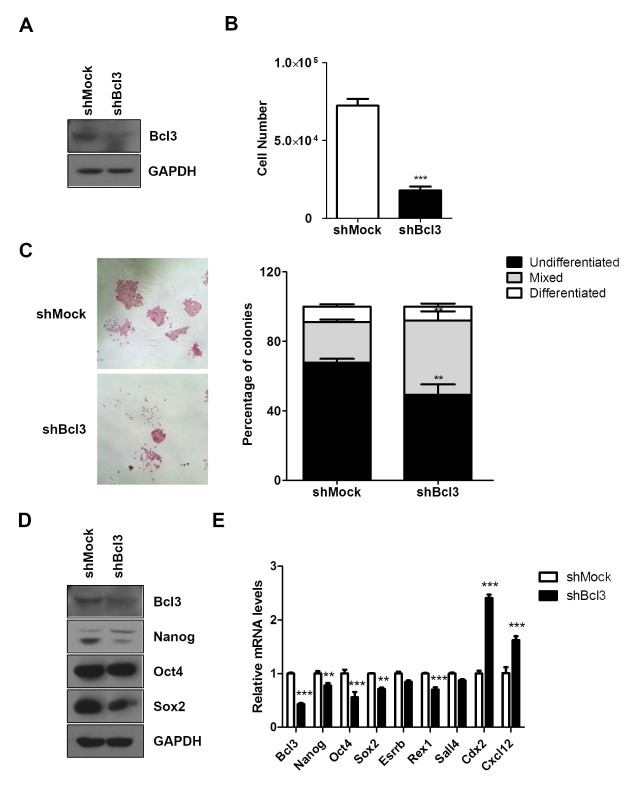

Insufficiency of Bcl3 attenuates pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells

To investigate whether Bcl3 regulates the pluripotency of mESC, we generated a knockdown of Bcl3 in E14 using shRNA. Western blot analysis showed a lower level of Bcl3 protein in E14 infected with Bcl3 shRNA (shBcl3) than control mESC (shMock) (Fig. 2A). The proliferation ability of shBcl3 was determined through examination of proliferation of low-density mESCs in a 24-well culture plate. After 3 days, the number of trypsinized shBcl3 showed a remarkable 4-fold decrease compared with that of shMock (Fig. 2B). Alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining, a marker of undifferentiated ESCs, showed that the colonies of undifferentiated mESCs were typically packed and stained a deep reddish color. We confirmed that shBcl3 formed fewer completely undifferentiated AP-positive colonies compared with shMock (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the proportions of differentiated colonies and mixed differentiating colonies in shBcl3 were higher than that in shMock.

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of Bcl3 attenuated pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells. (A) Western blot analysis of Bcl3 in E14 cells transfected with mock vector (shMock) and Bcl3 shRNA (shBcl3). GAPDH was used as an internal control. (B) Cell proliferation assay of shMock and shBcl3. The cells were seeded on a 24-well culture plate at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well and cultured for 3 days. ***P < 0.005 vs shMock. (C) Alkaline phosphatase staining of shMock and shBcl3. After AP staining, the colonies were scored, and the percentages of undifferentiated, mixed, and differentiated colonies were calculated. The bar graph shows the statistical evaluation. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 3). P values were calculated by using two-way ANOVA. **P < 0.01 vs shMock. (D) Western blot analysis of pluripotent-related genes, Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2 in shMock and shBcl3. GAPDH was used as an internal control. (E) Quantitative RT-PCR of pluripotent related genes in shMock and shBcl3. The data are normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to shMock. The error bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 3). P values were calculated by using two-way ANOVA. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 vs shMock.

In the evaluation of whether the expression of pluripotency genes was changed in mESCs by the knockdown of Bcl3, western blot analysis revealed reduced expression of pluripotency genes, Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2 in shBcl3. At the transcriptional level, as assessed by qRT-PCR, shBcl3 not only suppressed pluripotency genes but also, significantly increased differentiation genes, including ectodermal marker Cxcl12 and trophectodermal marker Cdx2 (Fig. 2D). Our results indicated the requirement of Bcl3 for maintenance of mESC pluripotency.

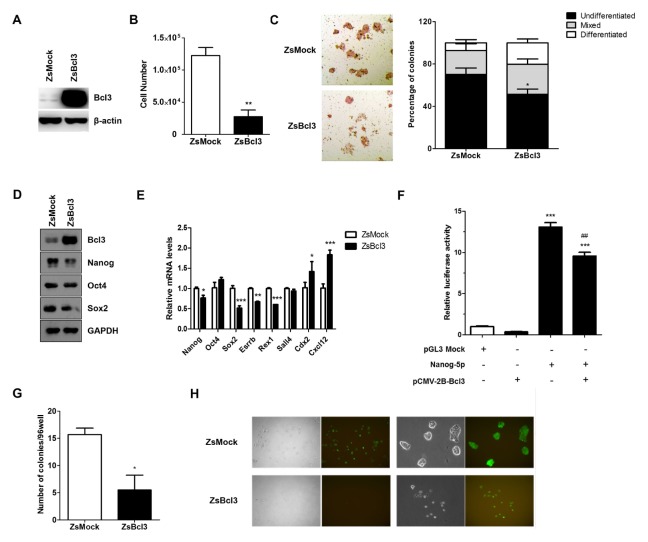

Excessive Bcl3 expression also attenuated pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells

To investigate whether Bcl3 was required for maintenance of mESC pluripotency, we generated the stable expression of Bcl3 in E14 by using a lentivirus. Western blot analysis revealed a marked overexpression in the level of Bcl3 protein in E14 infected with Bcl3 (ZsBcl3) compared with E14 infected with mock vector (ZsMock) (Fig. 3A). First, we evaluated that Bcl3 was involved in the self-renewal and proliferation of mESCs. The proliferation ability of ZsBcl3 was 5-fold lower than that of ZsMock (Fig. 3B), additionally, ZsBcl3 formed fewer completely undifferentiated colonies, and the proportion of mixed differentiating colonies was significantly increased compared with ZsMock (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of Bcl3 reduces pluripotency of mouse embryonic stem cells. (A) Western blot analysis of Bcl3 in E14 cells transfected with mock vector (ZsMock) and Bcl3 (ZsBcl3). β-Actin was used as an internal control. (B) The cell proliferation assay of ZsMock and ZsBcl3. **P < 0.01 vs ZsMock. (C) Alkaline phosphatase staining of ZsMock and ZsBcl3. The bar graph shows the statistical evaluation. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 3). P values were calculated by using two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05 vs ZsMock. (D) Western blot analysis and (E) quantitative RT-PCR of pluripotent related genes and differentiation related genes in ZsMock and ZsBcl3. The data are normalized to β-actin and expressed relative to ZsMock. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 3). P values were calculated by using two-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 vs ZsMock. (F) Luciferase reporter assay of Nanog in E14 cells. E14 was co-transfected with Nanog-5p and vectors as indicated. The transfected cells were cultured for 24 h and the luciferase activity was measured. Data were normalized to a Renilla luciferase control. The error bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 4). P values were calculated by using one-way ANOVA. ***P < 0.005 vs control, ##P < 0.01 vs Nanog-5p-only transfected cells. (G) Single cells of ZsMock and ZsBcl3 were sorted into 96-well plates by FACS and cultured for 5 days, after which the wells were scored for the presence of colonies. *P < 0.05 vs. ZsMock. Error bars indicate the mean ± SEM (n = 3). (H) The morphology of E14_ZsMock and E14_ZsBcl3. The cells were grown for 5 days and sorted for GFP-positive cells by FACS. Representative fluorescence microscopy images at 50× (left) and 200× (right) magnification are shown.

Bcl3 regulates transcription of Nanog by downregulating promoter activity

Bcl3 has been reported to act as a transcriptional regulator of genes associated with immune homeostasis, cellular proliferation, and survival (18, 19). We established the hypothesis that Bcl3 acts as a transcriptional regulator of pluripotent related genes in mESCs. Western blot analysis revealed that Nanog expression was markedly decreased in ZsBcl3. Moreover, other pluripotent factors were slightly affected in ZsBcl3 (Fig. 3D). Similarly, qRT-PCR assay showed that Bcl3 overexpression decreased expression of the Nanog transcript. In ZsBcl3, Nanog, Sox2, Esrrb and Rex1 transcript levels were decreased in comparison with ZsMock and differentiation genes were induced. To evaluate whether the reduction of Nanog expression in ZsBcl3 was regulated by Bcl3, we studied whether Bcl3 regulates the promoter activity of Nanog by using a luciferase reporter assay. E14 was co-transfected with Nanog-5p plasmid, including 2.5 kb before the proximal promoter of Nanog gene, and the Bcl3 overexpression plasmid. The results showed a significant decrease in the activity of the Nanog promoter in Bcl3-overexpressing E14. Based on these data, we concluded that Bcl3 downregulated Nanog expression through reduction of Nanog promoter activity in mESCs.

Excessive Bcl3 expression reduces clonogenic potential in mouse embryonic stem cell

To study the clonogenicity of ZsBcl3, we performed a single cell-repopulating assay. After single cells were sorted into a 96-well plate by flow cytometry, we examined the proportion of undifferentiated GFP-positive colonies over 5 days. Our results revealed that ZsBcl3 showed markedly less clonogenic potential than ZsMock (Fig. 3F). We confirmed that ZsBcl3 resulted in more differentiation-like cells and fewer colonies. Also, ZsMock displayed a typical compact mESC colony morphology; in contrast, ZsBcl3 exhibited loosely attached cell morphology (Fig. 3G). These results provided supporting evidence for the hypothesis that abnormally expressed Bcl3 attenuate mESCs pluripotency and induce differentiation of mESCs.

DISCUSSION

ESCs can undergo self-renewal and differentiation into multi-lineage cells. Pluripotency of ESCs is maintained by a core regulatory network, which includes Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog (2). Expression levels of the core regulatory network control are interrelated, and this extended control of expression facilitates ESC maintenance (20). However, the precise regulatory mechanism for the regulation of the core regulatory network machinery is largely unclear. Here, we propose a novel protein, B cell leukemia/lymphoma 3 (Bcl3), which might control the adequacy of pluripotency and self-renewal potential of ESCs.

Accumulated data indicate that Bcl3 can interact with other transcriptional regulators, including the AP-1 transcription factors, c-Jun and c-fos (14), STAT1 (21), and PPARγ (22). Studies have also reported Bcl3 expression in different types of hematopoietic and solid tumors, yet its function in ESCs have not been investigated. In this report, we demonstrated that Bcl3 was involved in proliferation and self-renewal of mESCs via the regulation of Nanog expression. Nanog plays an essential role in the control of the pluripotency of ESCs, as well as in early embryonic development, through its activity as a master transcription factor of the core regulatory factors for pluripotency of mESCs. Notably, Nanog expression is restricted to pluripotent cells and Nanog downregulation causes loss of the ability for self-renewal and an acceleration of ESC differentiation (3, 4, 6). However, little is known about how Nanog expression is regulated. Here, we found that a novel factor, Bcl3, acts as a negative regulator of Nanog expression in mESCs. We found that the ectopic expression of Bcl3 decreased Nanog expression. To determine whether the downregulation of Nanog was a result of direct or indirect binding of Bcl3 to the Nanog promoter region, a luciferase reporter assay was performed. The results indicated that Nanog reporter activity was decreased when exposed to overexpressed Bcl3. Previous reports demonstrated that Bcl3 regulated Oct4 promoter activity and pluripotency genes in mESCs, and that the expression of Oct4 increased the expression of doxycycline-inducible Bcl3 in mESCs (17). However, there was no significant change in the Oct4 expression in our system. One explanation for this discrepancy was the different expression systems. In previous reports, ectopically induced expression of Bcl3 was increased 1.42-fold, which partially prevented cell differentiation and promoted Oct4 promoter activities. However, the ectopic expression of Bcl3 was 5.7-fold higher compared with control mESC, which eventually attenuated the pluripotency and promoted the differentiation of mESCs. Therefore, it is interesting that an excessive dose of Bcl3 negatively impacts mESC pluripotency. Collectively, we concluded that an adequate concentration of B cell leukemia/lymphoma 3 (Bcl3) is required for the pluripotency and self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs).

Although we found that Bcl3 might influence Nanog promoter activity in mESCs, the direct and indirect molecular mechanisms should be further investigated. Previously reported data clearly showed that Bcl3 repressed TORC3-transcription through recruitment of HDAC1 (16), as well as recruitment of HDAC-3 and -6 through association with Bcl3, to promoter repress transcriptional activity (23). Based on these previous reports, Bcl3 may downregulate Nanog promoter activity through recruitment of the HDAC family or other transcriptional repressors to promoters of Nanog, but this requires further investigation.

A previous study reported that p53 induced the differentiation of DNA-damaged ESCs through the direct suppression of Nanog expression (24). Downregulation of Nanog mRNA during ESC differentiation correlated with the induction of p53 transcriptional activity, which was confirmed by the p53 protein levels in Bcl3-overexpressing mESCs. The results showed that levels of the p53 protein was markedly increased in ZsBcl3 compared with ZsMock (Supplementary Fig. 1). Based on these results, we suggested that Bcl3 downregulated Nanog expression through p53 induction in mESCs.

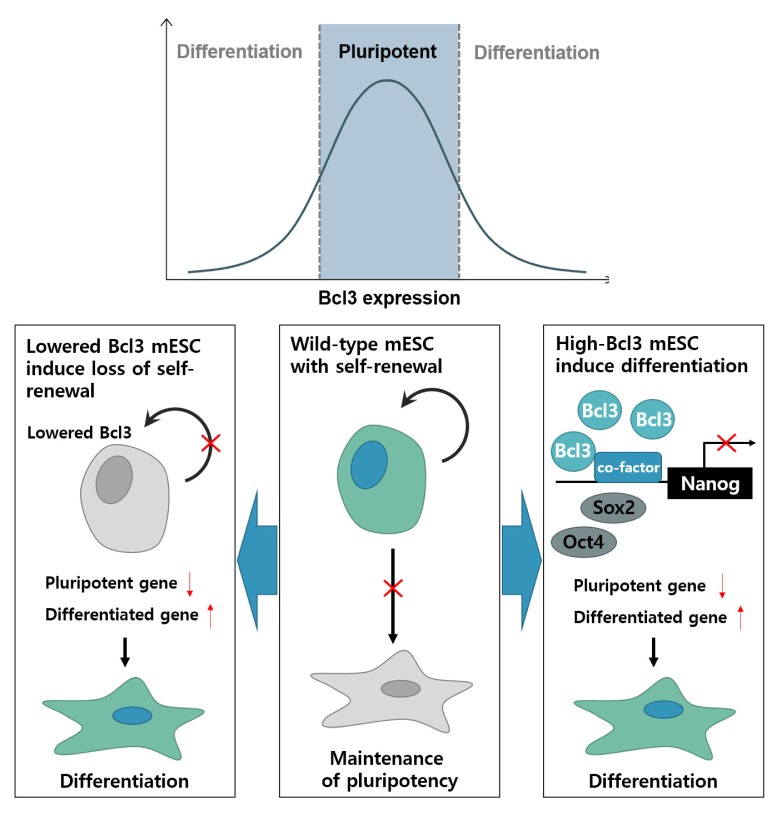

In conclusion, Bcl3 is highly expressed in mESCs and the knockdown of the Bcl3 gene attenuates the pluripotency of mESCs. Similarly, Bcl3 overexpression also attenuated the pluripotency of mESCs and promoted the differentiation of mESC through the downregulation of Nanog expression, which suggested that an adequate concentration of Bcl3 in mESCs performs a critical role in the maintenance of self-renewal of mESCs via regulation of Nanog transcriptional activity (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Regulation of Bcl3 expression is an essential for maintenance of mouse embryonic stem cell pluripotency. In the absence or overexpression of Bcl3, mouse embryonic stem cells lose pluripotency and differentiation is promoted. Reduction of Bcl3 in mESCs induces loss of self-renewal ability and induces differentiation. Overexpression of Bcl3 in mESCs also promotes differentiation through a reduction in Nanog promoter activity. After the suppression of Nanog promoter activity, the expression of pluripotency genes was decreased, and that of differentiation genes, was increased. Collectively, Bcl3 was required for pluripotency of mESCs and the regulation of Bcl3 expression is essential for the maintenance of mESC pluripotency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and differentiation

Mouse ES cells (E14tg2a line) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). mESCs were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (Welgene) containing 15% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1× non-essential amino acids (Welgene), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1,000 U/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (ESGRO, Millipore) on 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes. Embryoid body formation was performed in hanging drop culture at a concentration of 800 cells per 20 μl drop, without LIF.

Lentivirus production and induction of ESC

For gene overexpression, Bcl3 was cloned into the pLVX-EF1α-IRES-ZsGreen1 vector. LVX-293T cells were transfected using 2.5 μg pMD2G, 7.5 μg psPAX, 10 μg plasmid, and 30 μl Lipofectamine 2000 (ThermoFisher Scientific). For short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdowns, Bcl3 shRNA constructs were purchased from Sigma. Viral particles were collected 48 h after transfection and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter (Sartorius). Mouse ES cells were infected by replacement of the culture medium with 5 ml of viral supernatant and 5 ml complete medium in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma) and incubated for 16 h. Overexpressed mESCs were sorted for GFP expression using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). For knockdown experiments, the expression of shRNA was selected by addition of 5 μg/ml puromycin.

Single cell repopulation assay

pLVX-EF1α-IRES-ZsGreen1-Bcl3 transduced E14 cells were sorted for GFP expression using flow cytometry (BD FACS Aria I). Flow cytometry was used to place a single GFP-positive E14 in the well of a 96-well culture plate. Each well was coated with 0.1% gelatin and contained 200 μl complete medium. The medium was replaced with fresh, complete medium every 2 days. After 5 days, each well was examined for the growth of mouse ES cells by fluorescence microscopy (Zeiss). To measure the number of cells in a colony, we visually counted the cells in each of the 96 wells by using an inverted phase-contrast microscope at ×40 magnification.

Alkaline phosphatase staining

mESCs were seeded on a 0.1% gelatin coated 24-well culture plate at a density of 3 × 103 cells/well and cultured for 3 days. Alkaline phosphatase staining was performed using the Alkaline Phosphatase Kit (Millipore) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated by using TRIzol Reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific) and cDNA was synthesized with PrimeScript 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara) using oligo(dT) primer. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed on a LightCycler 96 Real-Time PCR System (Roche) using FastStart Essential DNA Green Master (Roche). The relative expression of each gene was normalized to β-actin expression. The primer sequences used are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted by using RIPA lysis buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF (Millipore). PVDF was probed with primary antibodies against Nanog (Bethyl), Bcl3, Sox2, Oct4, p53, GAPDH, β-actin (Santacruz) followed by the application of HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. HRP was detection by the application of ECL reagent (Millipore) to PVDF and exposure to x-ray films.

Luciferase reporter assay

E14tg2a cells were plated in 24-well plates and were transfected with Nanog-5P, which contains 2.5 kb of the 5’ promoter region of the mouse Nanog gene (Addgene), pCMV-2B-Bcl3 using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (ThermoFisher Scientific). pCMV-2B-Bcl3 was cloned into the multiple cloning site (BamHI and XhoI) of the pCMV Tag 2B vector (Agilent technologies). The cells were extracted 24 h after transfection and the extracted cells were analyzed by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay (Promega), with the luciferase activity measured in a multilabel plate reader (VICTOR3). The relative luciferase activity of each sample was normalized to Renilla activity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test, or one-way or two-way ANOVA. The data were reported as the mean ± standard deviation. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (NRF-2015M3A9B4066493, NRF-2015M3A9B4051053, NRF-2015R1A5A2009656, NRF-2014R1A2A1A11052311).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Suda Y, Suzuki M, Ikawa Y, Aizawa S. Mouse embryonic stem cells exhibit indefinite proliferative potential. J Cell Physiol. 1987;133:197–201. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041330127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niwa H. How is pluripotency determined and maintained? Development. 2007;134:635–646. doi: 10.1242/dev.02787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers I, Colby D, Robertson M, et al. Functional expression cloning of Nanog, a pluripotency sustaining factor in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2003;113:643–655. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00392-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitsui K, Tokuzawa Y, Itoh H, et al. The homeoprotein Nanog is required for maintenance of pluripotency in mouse epiblast and ES cells. Cell. 2003;113:631–642. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers I, Silva J, Colby D, et al. Nanog safeguards pluripotency and mediates germline development. Nature. 2007;450:1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/nature06403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuroda T, Tada M, Kubota H, et al. Octamer and Sox elements are required for transcriptional cis regulation of Nanog gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:2475–2485. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.6.2475-2485.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodda DJ, Chew JL, Lim LH, et al. Transcriptional regulation of nanog by OCT4 and SOX2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24731–24737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Berg DL, Zhang W, Yates A, et al. Estrogen-related receptor beta interacts with Oct4 to positively regulate Nanog gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5986–5995. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00301-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohno H, Takimoto G, McKeithan TW. The candidate proto-oncogene bcl-3 is related to genes implicated in cell lineage determination and cell cycle control. Cell. 1990;60:991–997. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90347-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maldonado V, Melendez-Zajgla J. Role of Bcl-3 in solid tumors. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:152. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujita T, Nolan GP, Liou HC, Scott ML, Baltimore D. The candidate proto-oncogene bcl-3 encodes a transcriptional coactivator that activates through NF-kappa B p50 homodimers. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1354–1363. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue J, Takahara T, Akizawa T, Hino O. Bcl-3, a member of the I kappa B proteins, has distinct specificity towards the Rel family of proteins. Oncogene. 1993;8:2067–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Na S-Y, Choi J-E, Kim H-J, Jhun BH, Lee Y-C, Lee JW. Bcl3, an IκB protein, stimulates activating protein-1 transactivation and cellular proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28491–28496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Na S-Y, Choi H-S, Kim JW, Na DS, Lee JW. Bcl3, an IκB protein, as a novel transcription coactivator of the retinoid X receptor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30933–30938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.30933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hishiki T, Ohshima T, Ego T, Shimotohno K. BCL3 acts as a negative regulator of transcription from the human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat through interactions with TORC3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28335–28343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702656200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen CY, Lee DS, Yan YT, et al. Bcl3 Bridges LIF-STAT3 to Oct4 Signaling in the Maintenance of Naive Pluripotency. Stem Cells. 2015;33:3468–3480. doi: 10.1002/stem.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bours V, Franzoso G, Azarenko V, et al. The oncoprotein Bcl-3 directly transactivates through κB motifs via association with DNA-binding p50B homodimers. Cell. 1993;72:729–739. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90401-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SG, Chung C, Kang H, Kim J-Y, Jung G. Up-regulation of cyclin D1 by HBx is mediated by NF-κB2/BCL3 complex through κB site of cyclin D1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31770–31777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loh YH, Wu Q, Chew JL, et al. The Oct4 and Nanog transcription network regulates pluripotency in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2006;38:431–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamaluddin M, Choudhary S, Wang S, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-inducible BCL-3 expression antagonizes the STAT/IRF and NF-κB signaling pathways by inducing histone deacetylase 1 recruitment to the interleukin-8 promoter. J Virol. 2005;79:15302–15313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15302-15313.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang J, Williams RS, Kelly DP. Bcl3 interacts cooperatively with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) coactivator 1α to coactivate nuclear receptors estrogen-related receptor α and PPARα. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4091–4102. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01669-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viatour P, Dejardin E, Warnier M, et al. GSK3-mediated BCL-3 phosphorylation modulates its degradation and its oncogenicity. Mol Cell. 2004;16:35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin T, Chao C, Saito S, et al. p53 induces differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells by suppressing Nanog expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:165–171. doi: 10.1038/ncb1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.