Abstract

Background and Purpose

Carotid plaques are a strong risk factor for ischemic stroke, and plaque rupture poses an even higher risk. Although many studies have investigated the pathogenic mechanisms of carotid plaque formation, few have studied the differences in molecular mechanisms underlying the rupture and non-rupture of carotid plaques. In addition, since early diagnosis and treatment of carotid plaque rupture are critical for the prevention of ischemic stroke, many studies have sought to identify the important target molecules involved in the rupture. However, a target molecule critical in symptomatic ruptured plaques is yet to be identified.

Methods

A total of 79 carotid plaques were consecutively collected, and microscopically divided into ruptured and non-ruptured groups. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction array, proteomics, and immunohistochemistry were performed to compare the differences in molecular mechanisms between ruptured and non-ruptured plaques. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure the differences in ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) levels in the serum.

Results

The expression of several mRNAs and proteins, including ABCA1, was higher in ruptured plaques than non-ruptured plaques. In contrast, the expression of other proteins, including β-actin, was lower in ruptured plaques than non-ruptured plaques. The increased expression of ABCA1 was consistent across several experiments, ABCA1 was positive only in the serum of patients with symptomatic ruptured plaques.

Conclusions

This study introduces a plausible molecular mechanism underlying carotid plaque rupture, suggesting that ABCA1 plays a role in symptomatic rupture. Further study of ABCA1 is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Keywords: Carotid arteries, Plaque, ABCA1, Rupture, Proteomics, Biomarkers

Introduction

Ischemic stroke is one of the leading causes of lifelong disability and death worldwide. It is classified into various subtypes according to pathogenesis. Large artery atherosclerosis is the most common subtype of ischemic stroke in Korea. Of all ischemic strokes, 15% to 20% are attributable to carotid artery plaques [1]. In patients with carotid atherosclerosis, the risk of ischemic stroke increases with plaque volume and degree of stenosis. Therefore, carotid endarterectomy (CEA) or carotid artery stenting (CAS) is recommended for patients with severe stenosis [2-4]. Regardless of the degree of stenosis, a ruptured plaque increases the risk of ischemic stroke [5,6]. Therefore, distinguishing ruptured plaques from non-ruptured ones, and preventing rupture are critical. Although the development of carotid imaging has recently enhanced the detection of carotid plaque rupture, carotid imaging itself still has limitations [5,7,8]. To improve early detection, several studies have attempted to identify carotid plaque rupture using circulating biomarkers [9-12], but have ultimately failed to prove their clinical significance [9].

Understanding the molecular mechanisms of plaque rupture can be helpful for the identification of candidate biomarkers of rupture. Further, such information might allow detection of new therapeutic targets for the prevention and treatment of plaque rupture. A large lipid core, inflammation, and fibrous cap thinning are known to be associated with carotid plaques that are vulnerable to rupture [6,13]. Tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have been suggested to play important roles in the rupture of carotid plaques. In our previous study, MMP-2 and -9 were shown to be critical for carotid plaque rupture [10]. Considering a previous report suggesting the relationship between MMP-9 and other proteins, including ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) [14], it could be hypothesized that these proteins, including ABCA1, are involved in the pathological process of plaque rupture. Proteomics and other detailed cellular and molecular investigations could further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of carotid plaque rupture, and lead to the identification of ideal biomarkers and new therapeutic targets in patients with ruptured plaques, preventing future instances of ischemic stroke.

In this study, we investigated the differences between molecular mechanisms underlying carotid plaque rupture and non-rupture, using proteomics, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) array, and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Across all these experiments, ABCA1 levels were significantly different in the patients with ruptured plaque; therefore, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed to evaluate the utility of ABCA1 as a serological biomarker of plaque rupture (Supplementary Figure 1).

Methods

Subjects and tissue sampling

We collected samples of carotid plaques from patients with carotid artery disease were undergoing CEA at Kyung Hee University Hospital between March 2009 and December 2015. Symptomatic carotid plaque was defined as significant (>50%) stenosis of the ipsilateral carotid artery, causing an ischemic lesion or relevant transient neurological deficit within 6 months. Detailed clinical information was obtained from each patient, with particular attention to carotid-territory ischemic events. Serologic biomarkers can be affected by atherosclerosis in other vascular beds. To avoid this effect, we exclusively included patients with ischemic stroke in the relevant carotid artery territory, and excluded those with stroke in a non-relevant arterial territory (e.g., contralateral carotid territory or posterior circulation). We also excluded patients with acute symptomatic coronary heart disease and peripheral arterial disease.

Carotid tissue samples were obtained immediately after surgical resection, and the morphology of the carotid plaque was systematically recorded by an experienced vascular surgeon. Tissue samples were digitally photographed, and then stored in 0.2 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 4℃. After the tissue was cut into 5-mm-thick transverse sections, each section was cut into two halves: one was processed for paraffin embedding, while the other was stored at –80℃ (using a method similar to that reported in our previous study) [10]. Plaques were classified into ruptured or non-ruptured groups based on microscopic findings [10].

This study was approved by an independent Ethics Committee at Kyung Hee University Medical Center (KMC IRB 1223-03). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to specimen collection.

Risk factors

Demographic and clinical information was obtained for each patient. Hypertension was defined as a history of antihypertensive medications, a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg, or a diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg at discharge. Diabetes was defined as the previous use of any antidiabetic medication or fasting blood glucose ≥126 mg/dL. Dyslipidemia was defined as the previous use of lipid lowering agents, fasting serum total cholesterol ≥240 mg/dL, or low-density lipoprotein ≥160 mg/dL. Subjects were classified as either smokers or non-smokers. History of ischemic heart disease was defined as a reported or documentation of any of the following: myocardial infarction; stable or unstable angina; previous coronary revascularization, such as percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft; or positive result in a stress test.

qPCR array

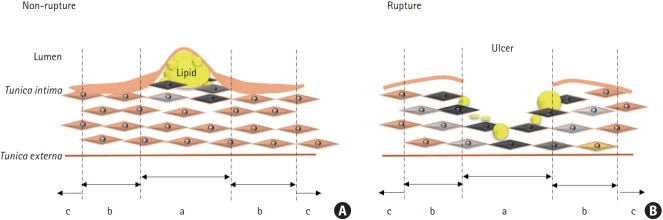

Portions of the ruptured and non-ruptured plaques were used. The total RNA from tissue samples, from zones a and b (Figure 1), was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The RNA levels were quantitatively analyzed, and equal amount of RNA from each group was used to perform qPCR. The qPCR array was performed using the Human Atherosclerosis RT2 ProfilerTM PCR array (Corbett Life Science, QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In this study, only statistically significant qPCR results were used for further analysis.

Figure 1.

A schematic comparison of (A) ruptured and (B) non-ruptured carotid plaques. Section (a) indicates either the thickest area of a non-ruptured plaque or the core area of a ruptured plaque, (b) is an area adjacent to the thickest area of a ruptured plaque or the core area of a ruptured plaques, and (c) is an unaffected area.

Proteomics

Protein sample preparation

Tissue samples from zones a and b (Figure 1) of ruptured and non-ruptured plaques were harvested using a mortar, liquid N2, and a homogenizer. These samples were then sonicated for 5 seconds, 15 to 20 times, with a sonicator (Qsonica, Newtown, CT, USA) in sample lysis solution composed of 7 M urea and 2 M thiourea (containing 4% [w/v] 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate and 40 mM dithiothreitol). After the samples were incubated on ice for 1 hour with occasional vortexing, they were centrifuged at 15,000 ×g for 30 minutes at 4℃. The pellet was discarded, while the soluble fraction was used for two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D PAGE). The protein concentration was assayed using the Bradford method.

2D PAGE

Immobilized pH gradient (IPG) dry strips (4 to 10 NL IPG, 13 cm, GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) were re-hydrated for 12 to 16 hours using a destreak rehydration solution, 0.5% IPG buffer, and loaded with 150 μg of sample. Isoelectric focusing (IEF) was performed at 20℃ using Ettan IPGphor 3 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For IEF, the voltage was linearly increased from 100 to 8,000 V over 7 hours for sample entry, followed by maintenance at a constant 8,000 V. Focusing was complete after 55 kVh. Prior to the second dimension, the strips were incubated for 15 minutes in equilibration buffer (75 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.8, containing 6 M urea, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 0.002% of 1% bromophenol blue stock solution, and 29.3% glycerol). This incubation first included 1% dithiothreitol, then 2.5% iodoacetamide. The equilibrated strips were inserted into SDS-PAGE gels (13×18 cm, 12%), and processed using the SE600 2D system (GE Healthcare, Holliston, MA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The 2D gels were run at 20℃ for 1,700 Vh, and were then stained with silver staining solution (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden).

Image analysis

Quantitative analysis of the digitized images was performed using ImageMasterTM 2D Platinum 7.0 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) software, according to the protocols provided by the manufacturer. The intensity of each spot was normalized to the total intensity of all valid spots. Protein spots that showed at least two-fold significant difference in the expression level compared with those of control samples were selected for further analysis.

Peptide mass fingerprinting

For protein identification using peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF), we adopted the methods previously described by Fernandez- Patron et al. [15] Briefly, protein spots were excised from the 2D PAGE gels, digested using trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), mixed with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile/0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, and subjected to matrixassisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) analysis (Microflex LRF 20, Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA). Spectra were collected from 300 shots per spectrum, over a range of 600 to 3,000 m/z, and were calibrated using two-point internal calibration with trypsin auto-digestion peaks (m/z: 842.5099 and 2211.1046). The peak list was generated using FlexAnalysis 3.0 software (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The threshold used for peak selection was as follows: 500 for a minimum resolution of monoisotopic mass and 5 for signal-to-noise. The search program MASCOT, developed by Matrix Science (http://www.matrixscience.com/), was used for protein identification by PMF. The following parameters were used for database searches: trypsin as the cleaving enzyme, a maximum of one missed cleavage, iodoacetamide (Cys) as a complete modification, oxidation (Met) as a partial modification, monoisotopic mass, and a mass tolerance of ±0.1 Da. The PMF acceptance criteria were based on probability scoring.

Immunohistochemistry

Slides containing sections cut from paraffin-embedded tissue from zone a (Figure 1) were incubated at 80℃ for 30 minutes. Preheated samples were incubated in xylene four times for 3 minutes, and then serially rehydrated in 100%, 95%, 80%, 70%, and 50% ethanol for 3 minutes each. Slides were washed with tap water for >100 seconds to remove the ethanol. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the slides in 0.01 M sodium citrate (pH 6) in a 98℃ chamber for 15 minutes. The tissues were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in D-PBS for 5 minutes. Next, 0.3% H2O2 was added for 10 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase activity. The cells were incubated with a blocking solution of 10% normal serum in D-PBS for 60 minutes. Cells were incubated overnight in 2% normal serum in D-PBS containing primary antibodies, on a shaker, at 4℃. The primary antibodies used in this study were: anti-ABCA1 (1:100, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) (1:100, Thermo, Rockford, IL, USA), anti-Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) (1:200, Biorbyt, San Francisco, CA, USA), anti-cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44) (1:100, Abcam), anti-ferritin (1:50, Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX, USA), anti-perilipin 2 (PLIN2) (1:200, Biorbyt), anti-enolase 1 (ENO1) (1:100, Abcam), and anti-β-actin (ACTB) (1 μg/mL, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA). On the next day, secondary antibody, diluted in 2% normal serum in D-PBS, was added for 60 minutes. Anti-rabbit tetramethylrhodamine (Life Technologies, Rockford, IL, USA), goat-anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Rockford, IL, USA), and goat-anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes) were used as secondary antibodies. The samples were mounted with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole containing mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA).

ELISA

Serum samples were collected from patients with ruptured or non-ruptured plaques, and centrifuged at 1,000 ×g for 20 minutes. An ABCA1 ELISA Kit was used (LifeSpan, Seattle, WA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The ABCA1 detection limit was 31 pg/mL. Protein concentrations were estimated using an ELISA reader (Synergy H1 Hybrid reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) with an absorbance wavelength of 450 nm.

Bioinformatic analysis

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of ABCA1 was analyzed using the STRING database version 10.5 (https://string-db.org/). The database provides known and predicted physical and functional interactions, based on previous research derived from five main sources of genomic context predictions, high-throughput laboratory experiments, conserved co-expression, automated text-mining, and information in databases. To analyze ABCA1 interaction, Homo sapiens was selected as the organism, and the maximum number of primary interactions was set to 10. The thickness of strings represented the strength of data supporting the interactions. The analyzed PPI of the ABCA1 had an enrichment P-value of 2.03e-10. The network of proteins and their biological processes were classified based on the Gene Ontology (GO) database, and were highlighted in the figure in red, green, yellow, and white colors based on the biological processes.

Statistics

Baseline demographic data were expressed as mean±SD for continuous variables, and as frequency for categorical variables. Any significant differences between the experimental and control groups were assessed using t-tests, chi-square tests, and Fisher exact tests, as appropriate.

Differences between the ruptured and non-ruptured groups were evaluated using ImageMasterTM 2D Platinum 7.0 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden) software for proteomics and free PCR array data analysis software provided by the manufacturer of the RT2 ProfilerTM PCR array (QIAGEN) for qPCR (according to the manufacturer’s instructions). The t-tests and Fisher exact tests were also used to analyze the IHC and ELISA data, respectively. The P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 22.0 package for Windows (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Subjects

A total of 138 CEAs were performed during the study period. Seventy-nine carotid plaques were selected for this study. Thirty-nine plaques, from patients whose symptoms did not arise in the relevant artery territory, were excluded, and 20 were excluded because the specimens were omitted or were inappropriate for morphological assessment due to fragmentation.

When tissue specimens were classified based on microscopic morphology, rupture was present in 44 carotid plaques (55.7%) and absent in 35 carotid plaques (44.3%). The median (interquartile range) interval between symptom and CEA in the 51 symptomatic patients was 16 days (10 to 28). Symptomatic stenosis was more frequent in patients with ruptured plaques (38/44, 86.4%) than in those without ruptured plaques (13/35, 37.1%, P=0.001). The baseline demographic features are presented in Table 1. The molecular characteristics were compared between the ruptured cap area in ruptured plaques and the thickest area in non-ruptured plaques.

Table 1.

Comparison of ruptured and non-ruptured plaques based on macroscopic findings

| Variable | Ruptured (n=44) | Non-ruptured (n=35) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 37 (84.1) | 28 (80.0) | 0.636* |

| Age (yr) | 68.8±6.8 | 69.1±9 | 0.097† |

| Location (right) | 27 (61.4) | 17 (48.6) | 0.256* |

| Hypertension | 35 (79.5) | 34 (97.1) | 0.037‡ |

| Diabetes | 15 (34.1) | 16 (45.7) | 0.356* |

| Dyslipidemia | 28 (63.6) | 25 (71.4) | 0.464* |

| Current smoker | 12 (27.3) | 10 (28.6) | 0.898* |

| Ischemic heart disease | 7 (15.9) | 8 (22.9) | 0.434* |

| Contralateral carotid stenosis (>50%) | 19 (43.2) | 14 (40.0) | 0.776* |

| Stenosis degree§ | 74.9±16.3 | 73.7±19.2 | 0.189† |

| Symptomatic stenosis∥ | 38 (86.4) | 13 (37.1) | 0.001* |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±SD.

Chi-square test;

Independent t-test;

Fisher exact test;

Stenosis degree was calculated using the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial criteria;

Symptomatic stenosis implies stenosis in the ipsilateral carotid artery causing an ischemic lesion or relevant transient neurological deficit within 6 months.

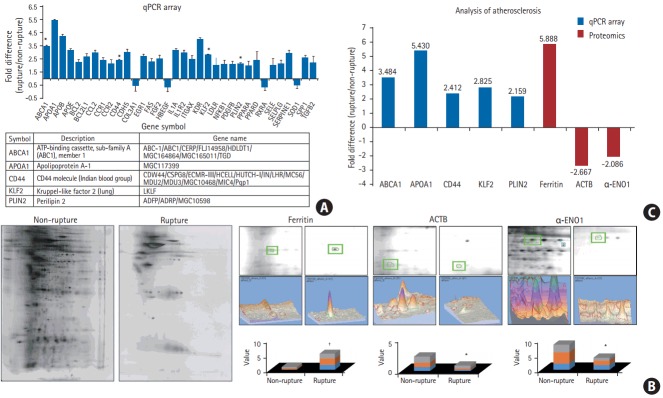

Quantitative PCR array

After comparing protein expression levels between patients with ruptured and non-ruptured plaques, RNA expression levels were measured using the Human Atherosclerosis qPCR array. Total RNA was extracted from the plaque tissue samples from each group, and their expression levels were compared. Among the 34 genes analyzed, the expression of five RNAs: ABCA1 (P<0.05), apolipoprotein A1 (APOA1) (P<0.05), CD44 (P<0.05), KLF2 (P<0.05), and PLIN2 (P<0.05), was found to be significantly higher in ruptured plaques than in non-ruptured plaques (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Differences in molecular expression levels between carotid plaques with or without rupture, as confirmed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) array and proteomic analysis. (A) A Human Atherosclerosis qPCR array demonstrated different levels of diverse mRNAs between carotid plaques with or without rupture, and (B) proteomic analysis showed several differentially expressed protein spots. In ruptured plaques, RNA levels of the ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1), apolipoprotein A1 (APOA1), cluster of differentiation 44 (CD44), Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2), and perilipin 2 (PLIN2) were significantly higher, as measured with the qPCR array. (C) The ferritin level was markedly higher, while the β-actin (ACTB) and α-enolase 1 (α-ENO1) levels were relatively lower, as measured by proteomics. *P<0.05; † P<0.001 Student t-test (two-tail distribution).

Proteomic analysis

To compare the changes in protein expression between ruptured and non-ruptured plaques, 2D proteomic analysis was performed. Three proteins that showed a greater than two-fold difference in expression level between the two groups were selected: ferritin, ACTB, and α-ENO1 (Figure 2B). Ferritin expression was significantly higher in ruptured plaques than in non-ruptured plaques (P<0.001), while the other two proteins had lower expression in ruptured plaques than in non-ruptured plaques. The P-values for the differences in the expression of ACTB and α-ENO1 between ruptured and non-ruptured plaques were P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively. Tissue samples were used from three patients per group (n=3).

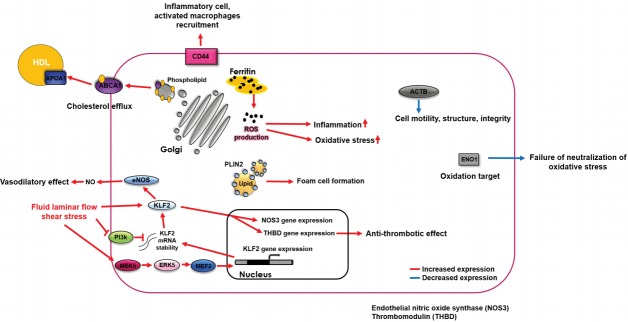

The observed differences in the protein and RNA levels between the two groups suggest that the molecular mechanisms underlying carotid plaque rupture ultimately lead to the increased expression of ABCA1, APOA1, CD44, KLF2, PLIN2, and ferritin, and reduced expression of ACTB and α-ENO1 (Figure 2C).

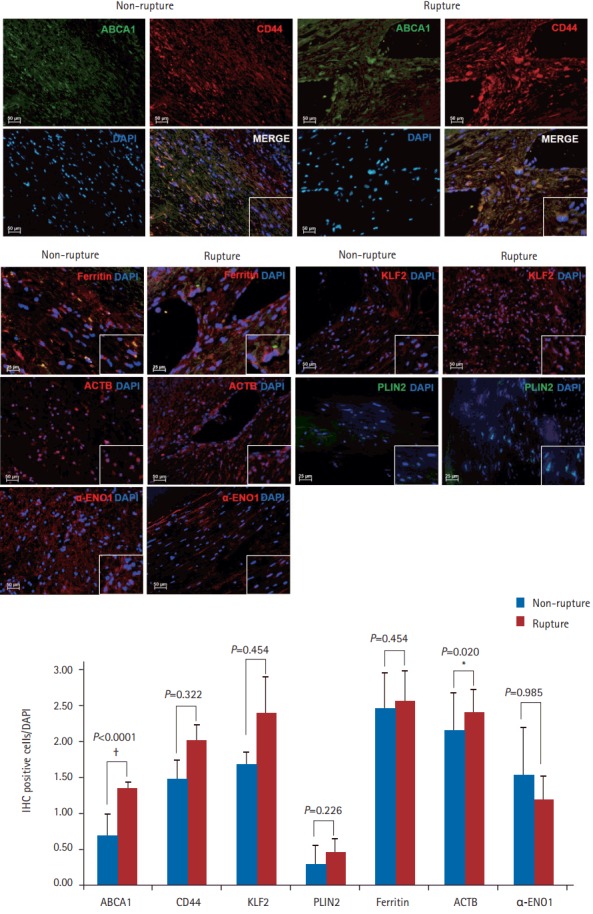

Immunohistochemistry

We used IHC to validate the differences in the protein levels between the two groups. Overall, ABCA1, CD44, KLF2, PLIN2, ferritin, and ACTB were more highly expressed in ruptured plaques than in non-ruptured plaques. However, only the differences in the expression levels of ABCA1 and ACTB were statistically significantly (P<0.0001 and P=0.020, respectively). When measured using IHC, the level of α-ENO1 tended to be higher in non-ruptured plaques than in ruptured plaques, although the difference was not statistically significant. All expression levels measured using IHC showed the same trend as those obtained from proteomics and qPCR, except for ACTB, which was found to be higher in ruptured plaques than in nonruptured plaques, although the opposite pattern was found using the other detection methods (n=3, P<0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Differences in ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) expression measured using immunohistochemistry (IHC). To confirm the differences in the expression level of several mRNAs and proteins, IHC was performed using several different antibodies. The levels of ABCA1 and β-actin (ACTB) were significantly increased in the ruptured plaques, while the other differences were not statistically significant. DAPI, 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; CD44, cluster of differentiation 44; KLF2, Krüppel-like factor 2; PLIN2, perilipin 2; α-ENO1, α-enolase1. *P<0.05; † P<0.001 Student t-test (two-tail distribution).

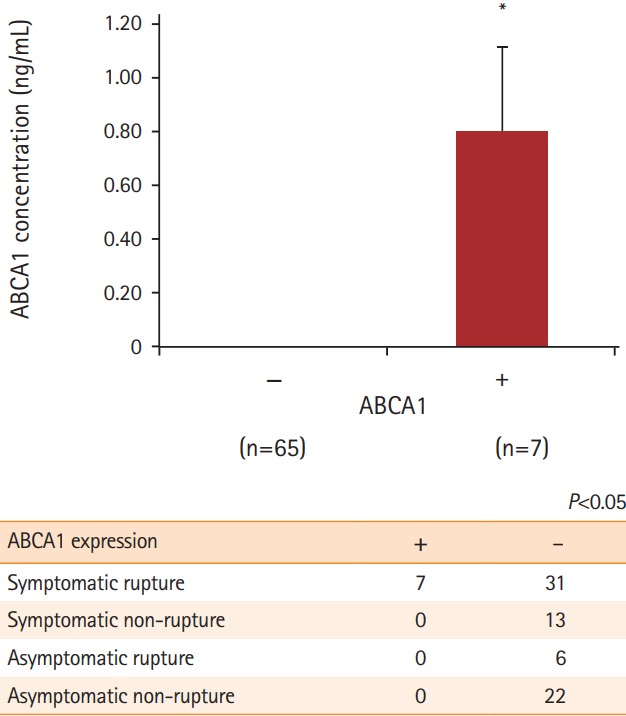

ELISA

We performed ELISA to detect ABCA1 in the serum obtained from both groups. We only detected ABCA1 in the serum of patients with ruptured plaques (P=0.013). Among those with symptomatic ruptured plaques, seven patients showed positive ABCA1 expression. In contrast, samples from patients with non-ruptured plaques and asymptomatic rupture had no ABCA1 expression (Figure 4). According to Fisher exact test, the frequency of ABCA1 expression in patients with symptomatic ruptured plaques was statistically significant (7/38 [18.4%] in patients with ruptured plaques vs. 0/41 [0.0%] in patients with non-ruptured plaques or asymptomatic plaques, P=0.038).

Figure 4.

The possibility of ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) as a new biomarker to identify symptomatic carotid plaque rupture using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). To determine whether ABCA1 can be detected in the serum of patients with carotid plaques, serum level of ABCA1 was measured using ELISA. Only the patients with symptomatic ruptured plaques tested positive for ABCA1, which led us to hypothesize that it could be used as a biomarker for symptomatic carotid plaque rupture. *P<0.05 Fisher exact test.

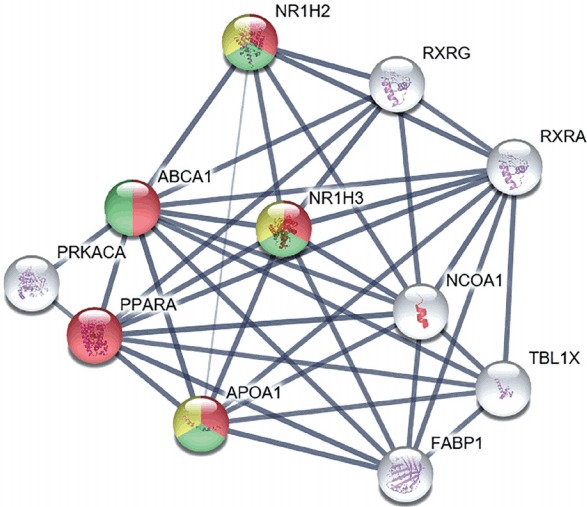

Bioinformatic analysis

We studied the biological processes of the proteins associated with ABCA1, according to the GO database. The proteins highlighted in various colors participate in specific biological processes related to the regulation of lipid transport, cholesterol homeostasis, and immune response (Figure 5). Further, bioinformatic analysis revealed that ABCA1 regulates inflammatory reactions by blocking carotid plaque formation. We found that ABCA1 has primary relationships with the following proteins: Protein kinase cAMP-activated catalytic subunit alpha, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, APOA1, fatty acid binding protein 1, nuclear receptor coactivator 1, transducin β-like 1X-linked, retinoid A receptor alpha, retinoid X receptor gamma, and nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H members 2 and 3 (NR1H2 and NR1H3).

Figure 5.

Bioinformatic analysis of ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1), revealing its preventive role in carotid plaque rupture and atherosclerosis progression during the inflammatory reaction. Bioinformatic analysis demonstrated that ABCA1 is involved in the regulation of lipid transport and in further inflammatory reactions involved in atherosclerosis progression. The thickness of strings describes the strength of data confidence. Among the primary interactions of ABCA1, 10 proteins with the highest confidence scores are shown in the figure. The biological processes of ABCA1 are distinguished by different colors: regulation of lipid transport in red, regulation of cholesterol transport and homeostasis in green, and negative regulation of cytokine-mediated signaling pathway and immune response in yellow. The remaining proteins that interact with ABCA1 are depicted by white color. NR1H2, nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 2; RXRG, retinoid X receptor gamma; RXRA, retinoid X receptor alpha; NR1H3, nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group H member 3; PRKACA, protein kinase A catalytic subunit alpha; PPARA, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha; NCOA1, nuclear receptor coactivator 1; APOA1, apolipoprotein A1; TBL1X, transducin beta like 1 X-linked; FABP1, fatty acid binding protein 1.

Discussion

In this study, we used several methods to compare ruptured and non-ruptured plaques, with respect to the expression levels of proteins of interest. Results obtained using the Human Atherosclerosis RT2 ProfilerTM PCR array demonstrated that the RNA expression levels of ABCA1, APOA1, CD44, KLF2, and PLIN2 were significantly higher in ruptured plaques than in non-ruptured plaques (Figure 2A and C). We used proteomic analysis to explore the differences in protein expression between the two groups. Ferritin expression was higher, while the expression of ACTB and ENO1 was lower in ruptured plaques than in non-ruptured plaques (Figure 2B and C). Based on the results from the qPCR array and proteomic analysis, IHC was performed to detect specific proteins (ABCA1, CD44, KLF2, PLIN2, ferritin, ACTB, and ENO1) in the cells of ruptured and non-ruptured plaque tissue, revealing that ABCA1 was more highly expressed in ruptured plaques than in non-ruptured plaques (Figure 3).

Several hypotheses have been proposed regarding the differences in the expression levels of RNA and proteins between ruptured and non-ruptured plaques. According to previous studies [16-19], ABCA1 exerts anti-inflammatory effects against atherosclerosis, as a mediator of its upstream proteins, NR1H2 and NR1H3, which decrease the levels of inflammatory factors, MMP-9, and tissue factors in atherosclerotic environments, and increase the expression of ABCA1. The immune response is further mediated by ABCA1 via suppression of the secretion of inflammatory cytokines. Similarly, APOA1 is known to exert protective effects against atherosclerosis through several mechanisms, including reverse cholesterol transport and promotion of cholesterol efflux from foam cells [20,21]. Considering that ABCA1 [16-19] and APOA1 [20,21] have beneficial effects against atherosclerosis, their levels might be increased in cells surrounding ruptured carotid plaques to confer protection against stresses that cause rupture. In addition, CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment, and activated macrophages with CD44 immunoreactivity contribute to atherosclerosis progression [22,23]. Therefore, an increase in CD44 expression in ruptured carotid plaques can be explained by the increased migration of inflammatory cells directly contributing to the rupture. It is well-known that KLF2 expression is increased in endothelial cells experiencing high shear-stress. Its expression induces a gene expression pattern that establishes functional quiescent differentiation of endothelial cells, which can facilitate cell survival [24,25]. Therefore, an increase in KLF2 expression in ruptured carotid plaques could also imply that the endothelial cells are influenced by high shear-stress, triggering this survival mechanism. In addition, PLIN2 is thought to induce the formation of foam cells, aggravating atherosclerosis [26,27]. Therefore, its increased expression could be directly associated with carotid plaque rupture. Ferritin is thought to be involved in oxidative stress and inflammation, and its increased levels are correlated with atherosclerosis progression [28,29]. We found that ferritin was more highly expressed in ruptured carotid plaques (than in non-ruptured plaques), which suggests that cells near a ruptured carotid plaque are under severe oxidative and inflammatory stress. Additionally, ACTB is an important cytoskeletal protein, and is highly associated with cell motility, structure, and integrity [30,31]. A decrease in the expression of ACTB, therefore, might increase cell vulnerability to damage, near a carotid plaque rupture. Finally, α-ENO1 is a target for oxidation, and its upregulation is a protective mechanism that neutralizes oxidative stress [32,33]. Therefore, a stress-inducing carotid plaque rupture could also increase the susceptibility of plaques to rupture by decreasing the expression of α-ENO1 in the surrounding cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Hypothetical alterations of molecular mechanisms in the cells in or near a carotid plaque rupture. Based on our results, it can be hypothesized that: (1) cells near a carotid plaque rupture increase their expression of ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) and apolipoprotein A1 (APOA1) to protect themselves from the stressors that cause rupture; (2) considering that CD44 is a well-known marker of inflammation, its increase in carotid plaque rupture might reflect increased migration of inflammatory cells, which would directly contribute to plaque rupture; (3) it is well-known that Krüppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) is increased in endothelial cells experiencing shear-stress, which can enhance survival; therefore, our finding that KLF2 was increased in carotid plaque rupture indicates that the cells adjacent to a plaque rupture experience considerable shear-stress, and therefore, activate their survival mechanisms; (4) perilipin 2 (PLIN2) is thought to induce the formation of foam cells; therefore, its increased levels could be directly associated with carotid plaque rupture; (5) ferritin is thought to be associated with oxidative stress and inflammation; therefore, increased ferritin expression in ruptured carotid plaques suggests that the cells near a rupture are under severe oxidative and inflammatory stress; (6) since β-actin (ACTB) is important for cytoskeleton, its decreased expression might indicate damage to the cells near a carotid plaque rupture; (7) both carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) and enolase 1 (ENO1) can enhance cell survival. Their decreased expression in the cells adjacent to a plaque rupture might reflect their increased vulnerability to stressors. HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CD44, cluster of differentiation 44; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NO, nitric oxide; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; PI3k, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; MEK5, mitogen-activated proteine kinase kinase 5; ERK5, extracellular-signal-regulated kinase 5; MEF2, myocyte enhancer factor 2; NOS3, nitric oxide synthase 3; THBD, thrombomodulin.

Altogether, our results consistently demonstrate that ABCA1 expression increases in ruptured plaques, leading us to hypothesize that it can be used as a serum biomarker of rupture. To test this hypothesis, ELISA was performed to compare the target serum protein levels between patients with ruptured and non-ruptured plaques. We performed ELISA based on results from previous studies that demonstrated that ABCA1, a membrane protein, can be detected in serum [34]. The serum expression levels of ABCA1 were significantly different between patients with ruptured and non-ruptured plaques (P=0.013). Seven of 38 patients (18.4%) with ruptured plaques tested positive for ABCA1, while none of the 41 patients (0.0%) with non-ruptured plaques and asymptomatic ruptured plaques showed ABCA1 expression (Figure 4). Although the frequency of ABCA1 expression in the serum of patients with ruptured plaques was not high, it was only detected in patients with symptomatic ruptured plaques. Our findings suggest that the pathogenesis of plaque rupture not only increases the production of ABCA1 at the RNA and protein levels, but also induces ABCA1 release into the serum. Although several prior studies have compared ABCA1 levels between atherosclerotic plaques and healthy control tissues, our study demonstrates the significance of ABCA1 in carotid plaque rupture. For example, Albrecht et al. [35] and Liu et al. [36] reported that ABCA1 expression, which facilitates cholesterol efflux from cells, has different patterns at the mRNA and protein levels. The mRNA level of ABCA1 was higher, while its protein level was lower, in atherosclerotic plaques than in control tissues [35,36]. Our results add to the existing evidence, demonstrating that ABCA1 level is different between ruptured and non-rupture plaques. Therefore, these results suggest that ABCA1 can be used as a serological biomarker for symptomatic ruptured plaques.

To examine the role of ABCA1 in carotid plaque rupture, we performed bioinformatic analysis using the STRING database. We found that several proteins were linked with ABCA1. The biological processes of these linked proteins were interpreted using the GO database. The primary associations of ABCA1, 10 different proteins with the highest database confidence, and their connections were illustrated in Figure 5, the colors were used as an indicator of the biological process of each protein. The proteins highlighted in red, green, and yellow are known to be involved in regulation of lipid transport, regulation of cholesterol transport and homeostasis, and cytokine-mediated signaling pathways and immune responses, respectively (Figure 5). Notably, activation of NR1H2 and NR1H3 is known to play an important role in inflammatory signaling by decreasing the levels of inflammatory factors such as MMP-9 and toll like receptor (TLR) 2, 4, and 9 expression in atherosclerotic aortas, whereas activation of ABCA1, an anti-inflammatory mediator of NR1H2 and NR1H3, negatively regulates cytokine-mediated signaling pathways and immune response. This finding suggests that ABCA1 participates in anti-inflammatory signaling, preventing inflammatory reactions and further atherosclerosis progression. In addition, NR1H2, NR1H3, and ABCA1 play a role in the negative regulation of macrophage-derived foam cell differentiation. This finding indicates that ABCA1 can slow atherosclerosis progression by inhibiting activated macrophages around a ruptured carotid artery.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the numbers of ruptured and non-ruptured plaques were considerably small. Recently, the number of CEAs performed in Korea has decreased abruptly with the development of CAS. Therefore, the opportunity to acquire and study carotid plaques, and their molecular mechanisms, is also decreasing. Secondly, we were unable to compare genes other than the 84 associated with atherosclerosis because we used a QIAGEN Human Atherosclerosis RT2 ProfilerTM PCR array. This may have introduced some discrepancy between the results from proteomic analysis and the qPCR array. Further, ELISA showed a low detection rate for the expression of ABCA1. Therefore, we could not compare the mean values between the two groups. In addition, the contamination by atherosclerosis involving other vascular beds, such as coronary and/or other peripheral arteries, is possible. However, no patients exhibited symptoms in other vascular beds within 6 months of surgery, and we excluded the patients with stroke in a non-relevant artery territory to avoid these effects. Thirdly, the duration of symptomatic carotid plaque may have affected the results. In the present study, symptomatic carotid plaque was defined as significant (>50%) stenosis in the ipsilateral carotid artery, causing an ischemic lesion or relevant transient neurological deficit within 6 months. Although we used the 6-month duration based on previous studies and the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines [37-39], there is no consensus on the duration criteria for symptomatic carotid plaque yet. Additionally, the 6-month duration might not be suitable for the evaluation of the molecular profiling of symptomatic carotid plaque because it may be too long, considering that the levels of various plasma proteins could normalize within a few weeks after the stroke, even though a previous study showed that the levels of some important plasma proteins were higher in patients with acute coronary syndrome even after 6 months [40]. This might be the reason that only a small number of patients with symptomatic carotid plaque tested positive for ABCA1. Therefore, to overcome this limitation, serial evaluation of ABCA1 levels might be needed after the stroke to allow the future study of symptomatic carotid plaques. Finally, considering that cap erosion of carotid plaque could be involved in cerebral infarction and/or transient cerebral ischemic attack, it would be preferable to separately analyze patients with only cap erosion. However, the number of patients with cap erosion was 11 in the present study, which was not sufficient for analysis, as shown by a previous study [41]. Moreover, because we wanted to identify factors involved in cap rupture, cap erosion was included in the non-rupture group, and all the experiments were carried out based on this classification.

Conclusions

The expression of the proteins ABCA1, CD44, KLF2, PLIN2, ferritin, ACTB, CAIX, and ENO1 was significantly different between ruptured and non-ruptured carotid plaques. As described above, each of these factors either contributed to plaque rupture or helped to protect the cells adjacent to ruptured plaques. This study is very important because it describes the detailed protein and RNA expression levels in carotid plaque rupture. Therefore, we believe that our results contribute valuable information to the clinical efforts to stabilize carotid plaques and prevent their rupture. It is possible that ABCA1 will eventually be used in a clinical setting to detect symptomatic ruptured plaques.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea, which is funded by: the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (2015R1A2A2A04004865); a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI); the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI17C2160); the Korea Drug Development Fund (KDDF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy, and Ministry of Health and Welfare (KDDF-201609-02, Republic of Korea); the Medical Research Center (2017R1A5A2015395); and the Boryung Pharmaceutical Company, Korea. The data analyses, interpretation, and final manuscript preparation were performed independent of the financial sponsors.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.5853/jos.2017.02390.

Overall experimental scheme of this study was illustrated from mRNA or protein screening to serum level measuring. Especially, increased expression of RNAs or proteins were presented in red color and decreased expression in blue. ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) showed higher expression in rupture carotid plaque tissue compared to non-rupture carotid plaque tissue and this result was consistent with the detected ABCA1 level in serum. qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; APOA1, apolipoprotein A1; CD44, cluster of differentiation 44; KLF2, Krüppel-like factor 2; PLIN2, perilipin 2; ACTB, β-actin; ENO1, enolase 1; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

References

- 1.Mughal MM, Khan MK, DeMarco JK, Majid A, Shamoun F, Abela GS. Symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid artery plaque. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2011;9:1315–1330. doi: 10.1586/erc.11.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Peerless SJ, et al. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1491–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prabhakaran S, Rundek T, Ramas R, Elkind MS, Paik MC, Boden-Albala B, et al. Carotid plaque surface irregularity predicts ischemic stroke: the northern Manhattan study. Stroke. 2006;37:2696–2701. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000244780.82190.a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah PK. Mechanisms of plaque vulnerability and rupture. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(4 Suppl S):15S–22S. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02834-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu XS, Zhao HL, Cao Y, Lu Q, Xu JR. Comparison of carotid atherosclerotic plaque characteristics by high-resolution black-blood MR imaging between patients with first-time and recurrent acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1257–1261. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josephson SA, Bryant SO, Mak HK, Johnston SC, Dillon WP, Smith WS. Evaluation of carotid stenosis using CT angiography in the initial evaluation of stroke and TIA. Neurology. 2004;63:457–460. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000135154.53953.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenig W, Khuseyinova N. Biomarkers of atherosclerotic plaque instability and rupture. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:15–26. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251503.35795.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heo SH, Cho CH, Kim HO, Jo YH, Yoon KS, Lee JH, et al. Plaque rupture is a determinant of vascular events in carotid artery atherosclerotic disease: involvement of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9. J Clin Neurol. 2011;7:69–76. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2011.7.2.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl TB, Yndestad A, Skjelland M, Øie E, Dahl A, Michelsen A, et al. Increased expression of visfatin in macrophages of human unstable carotid and coronary atherosclerosis: possible role in inflammation and plaque destabilization. Circulation. 2007;115:972–980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.665893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mannheim D, Herrmann J, Versari D, Gössl M, Meyer FB, Mc-Connell JP, et al. Enhanced expression of Lp-PLA2 and lysophosphatidylcholine in symptomatic carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Stroke. 2008;39:1448–1455. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.503193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van der Wal AC, Becker AE. Atherosclerotic plaque rupture: pathologic basis of plaque stability and instability. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:334–344. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soumian S, Gibbs R, Davies A, Albrecht C. mRNA expression of genes involved in lipid efflux and matrix degradation in occlusive and ectatic atherosclerotic disease. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1255–1260. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.026161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez-Patron C, Castellanos-Serra L, Hardy E, Guerra M, Estevez E, Mehl E, et al. Understanding the mechanism of the zinc-ion stains of biomacromolecules in electrophoresis gels: generalization of the reverse-staining technique. Electrophoresis. 1998;19:2398–2406. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150191407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fitzgerald ML, Mujawar Z, Tamehiro N. ABC transporters, atherosclerosis and inflammation. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu R, Ou Z, Ruan X, Gong J. Role of liver X receptors in cholesterol efflux and inflammatory signaling (review) Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:895–900. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunham LR, Singaraja RR, Duong M, Timmins JM, Fievet C, Bissada N, et al. Tissue-specific roles of ABCA1 influence susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:548–554. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.182303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Attie AD, Kastelein JP, Hayden MR. Pivotal role of ABCA1 in reverse cholesterol transport influencing HDL levels and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1717–1726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith JD. Apolipoprotein A-I and its mimetics for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11:989–996. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boisvert WA, Black AS, Curtiss LK. ApoA1 reduces free cholesterol accumulation in atherosclerotic lesions of ApoE-deficient mice transplanted with ApoE-expressing macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:525–530. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.3.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cuff CA, Kothapalli D, Azonobi I, Chun S, Zhang Y, Belkin R, et al. The adhesion receptor CD44 promotes atherosclerosis by mediating inflammatory cell recruitment and vascular cell activation. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1031–1040. doi: 10.1172/JCI12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinscherf R, Wagner M, Kamencic H, Bonaterra GA, Hou D, Schiele RA, et al. Characterization of apoptotic macrophages in atheromatous tissue of humans and heritable hyperlipidemic rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 1999;144:33–39. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dekker RJ, Boon RA, Rondaij MG, Kragt A, Volger OL, Elderkamp YW, et al. KLF2 provokes a gene expression pattern that establishes functional quiescent differentiation of the endothelium. Blood. 2006;107:4354–4363. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das H, Kumar A, Lin Z, Patino WD, Hwang PM, Feinberg MW, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 (KLF2) regulates proinflammatory activation of monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6653–6658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508235103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Son SH, Goo YH, Chang BH, Paul A. Perilipin 2 (PLIN2)-deficiency does not increase cholesterol-induced toxicity in macrophages. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao X, Gao M, He J, Zou L, Lyu Y, Zhang L, et al. Perilipin1 deficiency in whole body or bone marrow-derived cells attenuates lesions in atherosclerosis-prone mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.You SA, Wang Q. Ferritin in atherosclerosis. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;357:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orino K, Lehman L, Tsuji Y, Ayaki H, Torti SV, Torti FM. Ferritin and the response to oxidative stress. Biochem J. 2001;357(Pt 1):241–247. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gunning PW, Ghoshdastider U, Whitaker S, Popp D, Robinson RC. The evolution of compositionally and functionally distinct actin filaments. J Cell Sci. 2015;128:2009–2019. doi: 10.1242/jcs.165563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanukoglu I, Tanese N, Fuchs E. Complementary DNA sequence of a human cytoplasmic actin. Interspecies divergence of 3’ non-coding regions. J Mol Biol. 1983;163:673–678. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castegna A, Aksenov M, Thongboonkerd V, Klein JB, Pierce WM, Booze R, et al. Proteomic identification of oxidatively modified proteins in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Part II: dihydropyrimidinase-related protein 2, alpha-enolase and heat shock cognate 71. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1524–1532. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu N, Zhang Y, Li H, Gao Z. Oxidative and nitrative modifications of alpha-enolase in cardiac proteins from diabetic rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He Y, Lin L, Cao J, Mao X, Qu Y, Xi B. Up-regulated miR-93 contributes to coronary atherosclerosis pathogenesis through targeting ABCA1. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:674–681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albrecht C, Soumian S, Amey JS, Sardini A, Higgins CF, Davies AH, et al. ABCA1 expression in carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Stroke. 2004;35:2801–2806. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147036.07307.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu HF, Cui KF, Wang JP, Zhang M, Guo YP, Li XY, et al. Significance of ABCA1 in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Exp Ther Med. 2012;4:297–302. doi: 10.3892/etm.2012.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneiderman J, Schaefer K, Kolodgie FD, Savion N, Kotev-Emeth S, Dardik R, et al. Leptin locally synthesized in carotid atherosclerotic plaques could be associated with lesion instability and cerebral emboli. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e001727. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.001727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cho KY, Miyoshi H, Kuroda S, Yasuda H, Kamiyama K, Nakagawara J, et al. The phenotype of infiltrating macrophages influences arteriosclerotic plaque vulnerability in the carotid artery. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:910–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dardé VM, de la Cuesta F, Dones FG, Alvarez-Llamas G, Barderas MG, Vivanco F. Analysis of the plasma proteome associated with acute coronary syndrome: does a permanent protein signature exist in the plasma of ACS patients? J Proteome Res. 2010;9:4420–4432. doi: 10.1021/pr1002017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spagnoli LG, Mauriello A, Sangiorgi G, Fratoni S, Bonanno E, Schwartz RS, et al. Extracranial thrombotically active carotid plaque as a risk factor for ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2004;292:1845–1852. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.15.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Overall experimental scheme of this study was illustrated from mRNA or protein screening to serum level measuring. Especially, increased expression of RNAs or proteins were presented in red color and decreased expression in blue. ATP-binding cassette subfamily A member 1 (ABCA1) showed higher expression in rupture carotid plaque tissue compared to non-rupture carotid plaque tissue and this result was consistent with the detected ABCA1 level in serum. qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; APOA1, apolipoprotein A1; CD44, cluster of differentiation 44; KLF2, Krüppel-like factor 2; PLIN2, perilipin 2; ACTB, β-actin; ENO1, enolase 1; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.