Abstract

Background

Type 1 diabetes is a condition in which the pancreas produces little or no insulin. People with type 1 diabetes must manage their blood glucose levels by monitoring the amount of glucose in their blood and administering appropriate amounts of insulin via injection or an insulin pump. Continuous glucose monitoring may be beneficial compared to self-monitoring of blood glucose using a blood glucose meter. It provides insight into a person's blood glucose levels on a continuous basis, and can identify whether blood glucose levels are trending up or down.

Methods

We conducted a health technology assessment, which included an evaluation of clinical benefit, value for money, and patient preferences related to continuous glucose monitoring. We compared continuous glucose monitoring with self-monitoring of blood glucose using a finger-prick and a blood glucose meter. We performed a systematic literature search for studies published since January 1, 2010. We created a Markov model projecting the lifetime horizon of adults with type 1 diabetes, and performed a budget impact analysis from the perspective of the health care payer. We also conducted interviews and focus group discussions with people who self-manage their type 1 diabetes or support the management of a child with type 1 diabetes.

Results

Twenty studies were included in the clinical evidence review. Compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose, continuous glucose monitoring improved the percentage of time patients spent in the target glycemic range by 9.6% (95% confidence interval 8.0–11.2) to 10.0% (95% confidence interval 6.75–13.25) and decreased the number of severe hypoglycemic events.

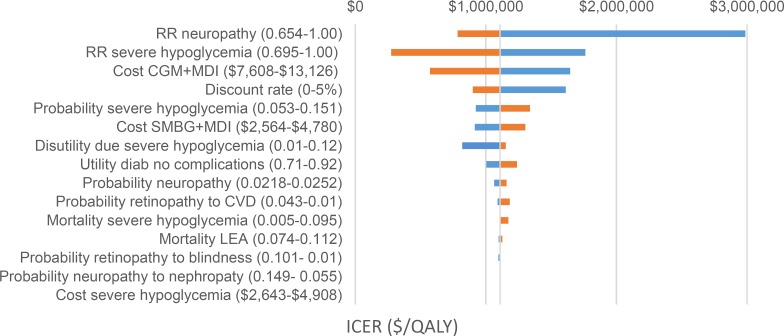

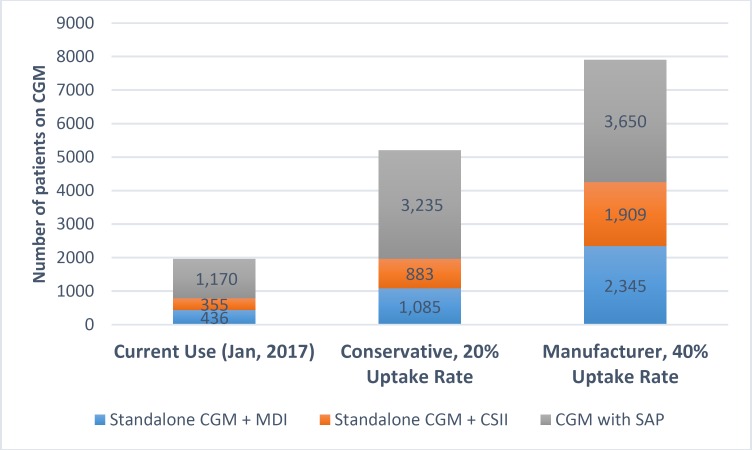

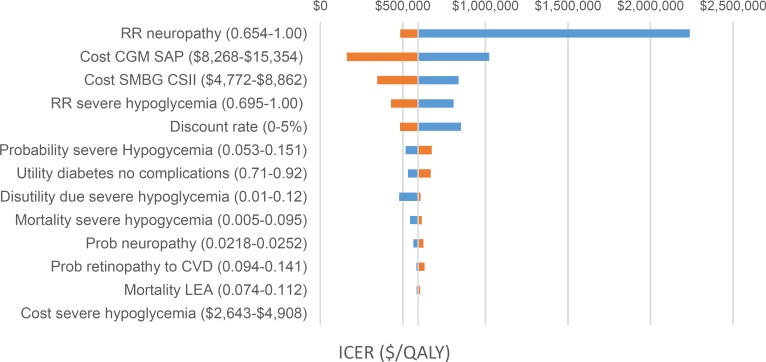

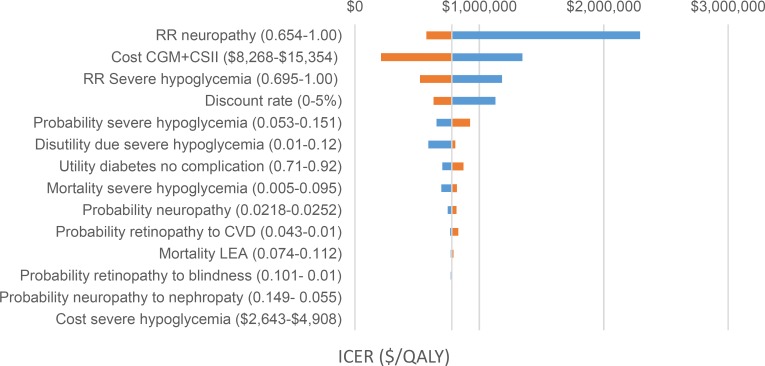

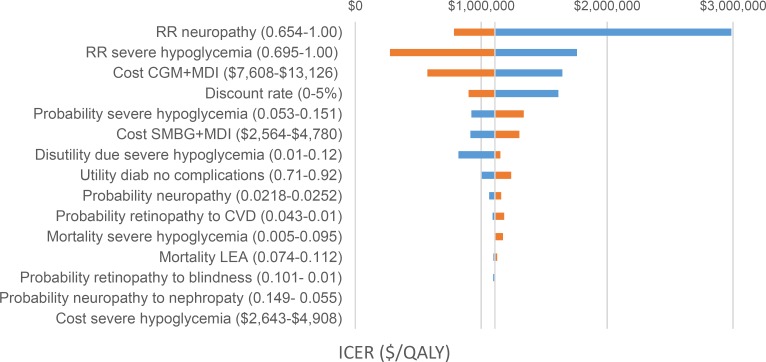

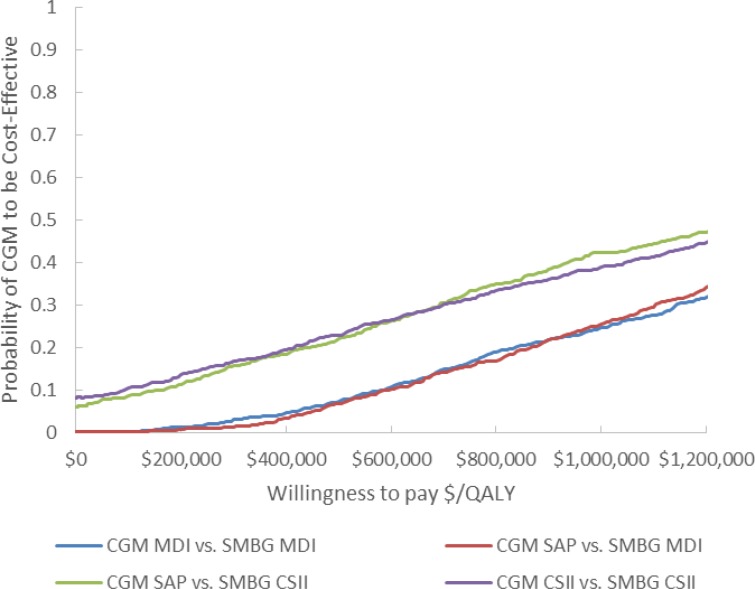

Continuous glucose monitoring was associated with higher costs and small increases in health benefits (quality-adjusted life-years). Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) ranged from $592,206 to $1,108,812 per quality-adjusted life-year gained in analyses comparing four continuous glucose monitoring interventions to usual care. However, the uncertainty around the ICERs was large. The net budget impact of publicly funding continuous glucose monitoring assuming a 20% annual increase in adoption of continuous glucose monitoring would range from $8.5 million in year 1 to $16.2 million in year 5.

Patient engagement surrounding the topic of continuous glucose monitoring was robust. Patients perceived that these devices provided important social, emotional, and medical and safety benefits in managing type 1 diabetes, especially in children.

Conclusions

Continuous glucose monitoring was more effective than self-monitoring of blood glucose in managing type 1 diabetes for some outcomes, such as time spent in the target glucose range and time spent outside the target glucose range (moderate certainty in this evidence). We were less certain that continuous glucose monitoring would reduce the number of severe hypoglycemic events. Compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose, the costs of continuous glucose monitoring were higher, with only small increases in health benefits. Publicly funding continuous glucose monitoring for the type 1 diabetes population in Ontario would result in additional costs to the health system over the next 5 years. Adult patients and parents of children with type 1 diabetes reported very positive experiences with continuous glucose monitoring. The high ongoing cost of continuous glucose monitoring devices was seen as the greatest barrier to their widespread use.

OBJECTIVE

This health technology assessment evaluated the clinical benefit, cost-effectiveness, and patient experiences of continuous glucose monitoring compared with usual care (i.e., self-monitoring of blood glucose using a finger-prick and a blood glucose meter) for the management of type 1 diabetes.

BACKGROUND

Health Condition

In Canada, approximately 3.4 million people live with diabetes. It is uncertain how many of those have type 1 diabetes. Some estimates from manufacturers of continuous glucose monitors in Canada, report that approximately 180,000 Canadians have type 1 diabetes, of whom 70,000 live in Ontario. Other estimates suggest that more than 300,000 people in Canada have type 1 diabetes, 150,000 of whom are in Ontario.1,2

In type 1 diabetes, the beta cells (insulin-producing cells) in the pancreas are damaged.3 The role of insulin in the body is to promote entry of glucose into the tissue cells. Inside the cell, glucose is metabolized to release energy, crucial for cell functioning. In most cases, type 1 diabetes is caused by an autoimmune process (the immune system attacks its own cells), resulting in a loss of beta cells. This eventually leads to high levels of glucose in the blood, affecting protein synthesis (protein-building) and other metabolic disorders such as diabetic ketoacidosis (too much acid in the blood).3 Over the long term, people with diabetes can experience serious complications, including kidney disease, heart disease, stroke, nerve damage, and damage to the eyes, leading to blindness.1

Diabetes is considered one of the most burdensome diseases for health care systems because of the time and resource costs related to managing diabetes and its complications.4

Clinical Need and Target Population

Patients with type 1 diabetes manage their blood glucose levels by frequently monitoring the amount of glucose in their blood and administering appropriate amounts of insulin to keep their blood glucose levels in the target range. Hyperglycemia (high blood glucose) can result in the long-term diabetes complications listed above. Hypoglycemia (low blood glucose) may lead to loss of consciousness, seizure, or coma.1

Type 1 diabetes affects people of all ages and genders. It is the most common type of diabetes in children and teens, accounting for at least 85% of diabetes cases in patients aged less than 20 years.5

Current Treatment Options

Typically, people with type 1 diabetes self-monitor their blood glucose levels using a blood glucose meter. Blood glucose levels are usually expressed in millimoles per litre (mmol/L) or milligrams per decilitre (mg/dL). To measure blood glucose levels with a blood glucose meter, a person must prick their finger and squeeze a drop of blood onto a test strip inserted into the meter. The meter then provides a readout of the blood glucose level. People with type 1 diabetes who use a meter usually take readings at regular intervals, including before meals, after meals, before and after physical activity, before driving, and during the night.

A useful laboratory measure for assessing long-term blood glucose management is glycated hemoglobin (A1C), which estimates average blood glucose concentrations over a period of 3 months. This is commonly expressed in terms of National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program units (%), International Federation of Clinical Chemistry units (mmol/mol), or estimated average glucose (mg/dL). Diabetes Canada (formerly the Canadian Diabetes Association) recommends an optimal A1C of ≤7% to prevent the long-term complications of diabetes.6

Health Technology Under Review

Continuous glucose monitoring provides an opportunity for patients to monitor their blood glucose levels more frequently. It is aimed at helping people with diabetes gain a better understanding of their blood glucose control in real time.

Continuous monitoring of blood glucose levels can be used with multiple daily injections of insulin or an insulin pump. Continuous glucose monitors can be separate from an insulin pump (called standalone continuous glucose monitors) or they can be part of a system that is integrated with an insulin pump (called a sensor-augmented insulin pump).7

Continuous glucose monitors consist of a sensor inserted underneath the skin, a transmitter, and a small monitor. Every few minutes, the sensor measures blood glucose levels in the interstitial fluid8 (fluid that surrounds tissue cells) and sends readings via the transmitter to the monitor, which displays the information.8 For some models, the information can also be transmitted to other devices using Bluetooth technology, so that family members or other caregivers can access blood glucose information.

Continuous glucose monitors that are currently licenced in Canada require regular finger-prick testing to calibrate, usually every 12 hours.7 Continuous glucose monitors that do not require calibration with a finger-prick are expected to reach the market in 2018. The sensors for continuous glucose monitors are intended to be used for no more than 7 days and must be replaced regularly.7 Sensors that last 4 months are in development.9

Regulatory Information

As of November 2016, Health Canada had granted licenses for continuous glucose monitors from two manufacturers. Medtronic (Brampton, Ontario) and Dexcom (San Diego, California) have licences for several generations of devices. For this assessment, we reviewed any Medtronic or Dexcom device that has been included in peer-reviewed publications since 2010. Table 1 summarizes the devices that have Health Canada licences and met the inclusion criteria for this assessment.

Table 1:

Summary of Included Devices

| Manufacturer | Device | Year | License Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexcom | G4 | 2013, 2014 | 91189 |

| G5 | 2016 | 97937 | |

| Medtronic | Glucose sensor | 2000, 2009 | 20654 |

| REAL-TIME transmitter | 2007, 2009, 2013, 2016 | 73839 | |

| Enlite glucose sensor | 2013 | 90691 | |

| 630G | 2016 | 97802 |

Source: Health Canada.10

Medtronic offers a sensor-augmented insulin pump. The continuous glucose monitor is integrated with the pump and includes a “low glucose suspend” feature, which shuts off the administration of insulin for up to 2 hours when blood glucose levels are below a predetermined threshold and the patient is not responding to alerts. This feature may be beneficial for patients with nocturnal (nighttime) hypoglycemia or hypoglycemia unawareness.

The Dexcom continuous glucose monitor is a standalone device, but it can be integrated with the Animas Vibe insulin pump (Animas Corporation, West Chester, Pennsylvania).

Because the scope of this assessment was limited to continuous glucose monitoring devices by manufacturers with Health Canada licences at the time of writing, devices such as the Dexcom SEVEN and the Abbott FreeStyle Navigator were not included in this health technology assessment. Because this assessment was focused on devices used to support patients’ continuous monitoring of their blood glucose levels, devices such as the iPRO2 CGM system (license number 85706) and the Abbot Freestyle Libre Pro (license number 97934), which are used only by health care professionals, were also excluded from this assessment.

Ontario Context

Most patients in Ontario are not reimbursed for the cost of purchasing a continuous glucose monitor. Individuals must pay out of pocket or have private insurance that covers these devices.

In Ontario, the cost of a continuous glucose monitor is publicly funded for people who qualify for the Ontario Disability Support Program and the Mandatory Special Necessities benefit, Ministry of Community and Social Services.11 The Ontario Public Drugs Program offers reimbursement for 3,000 blood glucose test strips per year for certain populations who use insulin to manage their diabetes (i.e., people aged 65 years or older; people who qualify for the Ontario Disability Support Program; Ontario Works recipients; clients of the Trillium Drug Program; residents of long-term care homes or homes for special care; and individuals enrolled in home care).

Ontario's Assistive Devices Program provides funding assistance for insulin pumps for people with type 1 diabetes who are unable to achieve good blood glucose control with multiple daily injections alone.12 To be eligible, patients must have demonstrated good adherence to diabetes management prior to starting pump therapy. Adults must have been on multiple daily injections for 1 year prior to starting insulin pump therapy; pediatric patients are not required to be on multiple daily injections. Since the cost of an insulin pump is covered as an insured device in Ontario, patients who use an insulin pump with integrated continuous glucose monitoring capabilities need to pay for only the continuous glucose monitoring transmitters and sensors.

International Context

Continuous glucose monitoring is in widespread use around the world, and many insurance providers offer some funding. Table 2 summarizes Canadian and international funding options for continuous glucose monitoring.

Table 2:

International Funding of Continuous Glucose Monitoring

| Country | Reimbursement Plan | Details of Fundinga |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | Regional funding and private insurance programs | Limited funding regionally; some funding through private insurance companies |

| Ontario | Assistive Devices Program, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care | Funding of pump costs for insulin pumps with integrated continuous glucose monitors |

| Some private insurance companies | Details vary by insurance company | |

| Czech Republic | Patient capitation model | Partial funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices |

| France | National insurance funding | Funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices |

| Germany | National insurance funding | Funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices |

| Netherlands | Regional insurance funding | Partial funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices |

| Norway | Tenders; regional | Funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices |

| Slovenia | National reimbursement funding | Funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices for the pediatric population only |

| Sweden | Regional insurance funding | Funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices |

| Switzerland | National reimbursement funding | Funding for continuous glucose monitoring devices |

| United Kingdom | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence diagnostic assessment | National Health Service funds under specific circumstances; the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline strongly recommends the use of continuous glucose monitoring in young people with impaired hypoglycemic awareness or frequent severe hypoglycemic events and adults who meet certain criteria.13,14 |

| United States | Some private insurance companiesb | Details differ depending on insurance company |

| Medicare | Funding for therapeutic continuous glucose monitoring devices |

Information was gathered in part from Dexcom (San Diego, California).

Blue Cross/Blue Shield, Aetna, Cigna, Humana, United Healthcare, Kaiser Permanente, Wellpoint.15

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

Research Question

Compared with usual care (i.e., self-monitoring of blood glucose using a blood glucose meter), what is the effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring (using standalone devices or integrated with insulin pumps) in the management of type 1 diabetes?

Methods

Research questions are developed by Health Quality Ontario in consultation with clinical experts, patients, health care providers, and other health system stakeholders.

Clinical Literature Search

We performed a literature search on January 24, 2017, to retrieve studies published from January 1, 2010, to the search date. We used the Ovid interface to search the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Health Technology Assessment, National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database (NHSEED), and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE); and we used the EBSCOhost interface to search the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Medical librarians developed the search strategies using controlled vocabulary (i.e., Medical Subject Headings) and relevant keywords. The final search strategy was peer reviewed using the PRESS Checklist.16 We created database auto-alerts in MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL and monitored them for the duration of the health technology assessment review, until February 28, 2017.

We performed targeted grey literature searching of health technology assessment agency sites and clinical trial registries. See Appendix 1 for the literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Clinical experts and manufacturers suggested that since continuous glucose monitoring technology has evolved over time, the cut-off year for our literature search should be 2010.

Literature Screening

A single reviewer reviewed the abstracts and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, we obtained full-text articles.

Types of Studies

We included randomized, controlled studies and observational studies that examined (1) the effectiveness of standalone continuous glucose monitors compared with standalone self-monitoring of blood glucose or (2) the effectiveness of continuous glucose monitors integrated with insulin pumps compared with insulin self-management strategies involving insulin pumps or multiple daily injections.

We did not include before-after studies, editorials, case series, or commentaries.

Types of Participants

We included studies of patients with type 1 diabetes. We also considered subgroup analyses by age category.

Types of Interventions

A continuous glucose monitor is any device that provides continuous monitoring of blood glucose, with the results available at any time for patient review. This device may be used alone in conjunction with an insulin pump or multiple daily injections, or it may be integrated into an insulin pump (sensor-augmented pump). Continuous glucose monitors may include additional features, such as high/low glucose alarms or a low glucose suspend option (for sensor-augmented pumps).

Types of Settings

We considered the outpatient setting, with devices used by patients to support management of their blood glucose levels.

Types of Outcome Measures

Time-related glucose variability: The time a patient spends inside (or outside) the target glucose range is usually preferred to A1C as a measurement of overall glucose management, because A1C can be misleading. Patients may spend their day swinging between high and low blood glucose levels; using A1C, which measures the 3-month blood glucose average, may mask this variability

Hypoglycemia: Hypoglycemia is categorized by severity. Hypoglycemia occurs when blood glucose levels fall below 4 mmol/L. Severe hypoglycemia is associated with adverse outcomes for patients. Severe outcomes require the assistance of another person and include seizure, loss of consciousness, and hospitalization

A1C levels: Despite the limitations of A1C (see above), it is commonly used by researchers to evaluate diabetes management. It can provide a good indication of long-term blood glucose levels, since blood cells survive in the body for 3 to 4 months. Diabetes Canada recommends that A1C levels not exceed 7.0%6

User satisfaction: We considered patient satisfaction, with a preference for validated measures of overall satisfaction and health-related quality of life. We also included parent or guardian satisfaction where available

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on study characteristics and risk-of-bias items. We used a data form to collect study information about:

Sources (i.e., citation information, contact details, study type)

Characteristics of participants, interventions, and comparators

Methods (i.e., study design, study duration in years, participant allocation, allocation sequence concealment, blinding, reporting of missing data, reporting of outcomes, and whether the study compared two or more groups)

Outcomes (i.e., outcomes measured, number of participants for each outcome, number of participants missing for each outcome, outcome definition and source of information, unit of measurement, upper and lower limits [for scales], and times at which outcomes were assessed)

We contacted study authors for clarification as needed.

Health Equity

During scoping, we did not identify any reported health inequities in relation to continuous glucose monitoring for patients with type 1 diabetes. Nonetheless, whenever available, we have reported distributional characteristics for people likely to be affected by equity, as outlined in PROGRESS-Plus.17

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was done using Review Manager.18 We did not conduct meta-analyses because of heterogeneity in the populations, interventions, and outcomes reported in the included studies. Instead, we have presented narrative syntheses. Where specific outcomes reported were consistent across included studies, we used forest plots for visual purposes, but did not pool estimates. Wherever possible, we reported effect sizes, along with 95% confidence intervals.

Quality of Evidence

We evaluated the quality level of the evidence for each outcome according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines.19,20. We then rated the studies based on the following considerations: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias, magnitude of effect, and dose-response gradient. We determined the overall quality to be high, moderate, low, or very low using a step-wise, structural methodology. The quality level reflects our certainty about the evidence.

We assessed the risk of bias for each study individually using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool to assess randomized controlled trials, and the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Non-randomized Studies (RoBANS) for observational studies (Appendix 2).21,22

Expert Consultation

Throughout this project, we sought expert consultation on the use of continuous glucose monitoring. Experts consulted included physicians who specialize in endocrinology and diabetes, in both adult and pediatric populations. We also consulted people from industry, specifically Medtronic and Dexcom representatives. The roles of the expert advisors were to inform us of the appropriate use of the technology, contextualize the evidence, and provide insight for our health technology assessment.

Results

Literature Search

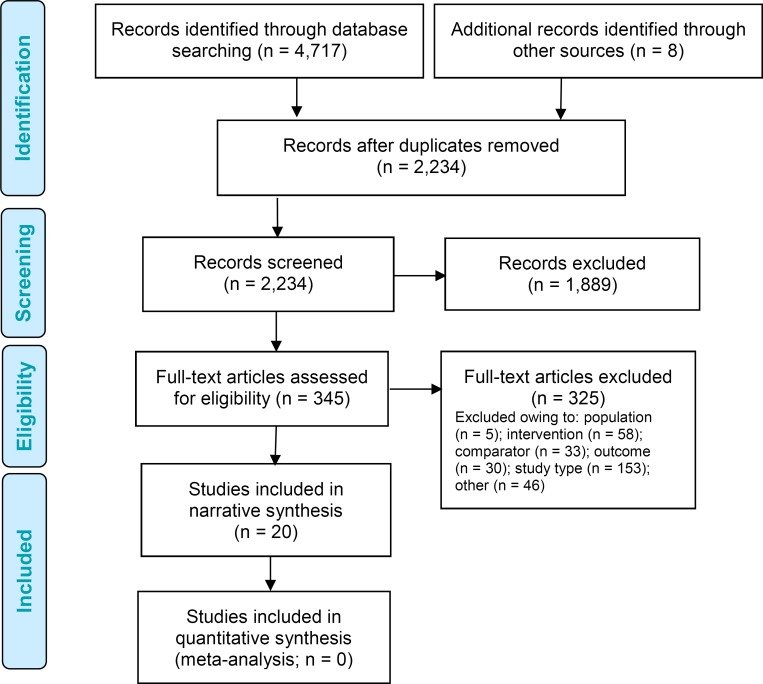

The literature search yielded 2,234 citations published between January 1, 2010, and January 24, 2017, after removing duplicates. We reviewed titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant articles. We obtained the full texts of these articles for further assessment. We searched the reference lists of the included studies, along with health technology assessment websites and other sources, to identify additional relevant studies. Eight citations were added, and 20 full text studies were included in the narrative synthesis.

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Clinical Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.23

Abbreviation: PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Details of the included studies are summarized in Table 3. The studies varied by continuous glucose monitoring device, inclusion criteria, patient age, and follow-up period. We identified 16 randomized controlled trials24–39 and four observational studies.40–43 Four studies exclusively focused on pediatric populations.26,29,34,37

Table 3:

Summary of Included Studies

| Author, Year Setting | Study Design (Trial Name)a CGM Device | Recruitment Period | Inclusion Criteria | Sample Size, I/C Intervention | Control | Study Period | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | Diagnosis | Glucose Control | Insulin Therapy | Other | |||||||

| Beck et al, 201724 United States 24 sites |

RCT (DIAMOND) Dexcom G4 | October 2014–May 2016 | ≥ 25 | Type 1 diabetes > 1 year | A1C between 7.5% and 10.0% | MDI | Not pregnant | 105/53 | CGM | SMBG | 24 weeks |

| Bergenstal et al, 201025 United States and Canada 30 sites |

RCT (STAR 3) Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | January 2007–December 2008 | 1–70 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 3 months | A1C between 7.4% and 9.5% | MDI | NA | 244/241 | SAP | MDI with SMBG | 1 year |

| Bukara-Radujkovic et al, 201126 Bosnia and Herzegovina 1 site |

RCT Medtronic MiniMed | 2006–2007 | 5–18 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 1 year | A1C ≥ 8% | MDI | NA | 40/40 | CGM | SMBG | 6 months |

| Hermanides et al, 201127 Europe 8 sites |

RCT Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | April 2007–January 2009 | 18–65 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 1 year | A1C ≥ 8.2% | MDI | NA | 43/35 | SAP | MDI with SMBG | 26 weeks |

| Hommel et al, 201428 Europe 8 sites |

RCT, crossover (SWITCH) Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | January 2008–July 2010 | 6–70 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 1 year | A1C between 7.5% and 9.5% | CSII > 6 months | CGM-naïve | 153 (total sample size) | Sensor on | Sensor off | 17 months |

| Kordonouri et al, 201229 Europe 5 sites |

RCT (ONSET) Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | February 2007–October 2008 | 1–16 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 1 year | NR | CSII | NA | 80/80 | SAP | CSII with SMBG | 1 year |

| Langeland et al, 201230 Norway 1 site |

RCT, crossover Medtronic MiniMed Guardian REAL-Time | January 2009–March 2009 | 18–50 | Type 1 diabetes > 3 years | A1C between 7% and 10% | MDI or CSII | > 1 serious hypoglycemic event in previous 6 months Untreated concomitant disease | 30 (total sample size) | CGM | SMBG | 20 weeks; 4 weeks of intervention, 8 weeks of washout before crossover |

| Lind et al, 201731 Sweden 15 sites |

RCT, crossover (GOLD) Dexcom G4 | February 2014–June 2016 | ≥ 18 | Type 1 diabetes > 1 year | A1C ≥ 7.5% | MDI | NA | 142 (total sample size) | CGM | Usual care | 26 weeks of intervention, 17 weeks of washout before crossover |

| Little et al, 201432 United Kingdom 5 sites |

RCT, 2 × 2 crossover (HypoCOMPaSS) Medtronic REAL-Time | NR | 18–74 | Type 1 diabetes, C-peptide negative | Impaired hypoglycemia awareness | NR | NA | 96 (total sample size) | CGM with MDI CGM with CSII | SMBG with MDI SMBG with CSII | 24 weeks |

| Ly et al, 201333 Australiab |

RCT Medtronic Paradigm Veo | December 2009–January 2012 | 4–50 | Type 1 diabetes | Hypoglycemia unawareness/ impaired awareness | CSII > 6 months | Not pregnant | 46/49 | SAP with low glucose suspend | CSII with SMBG | 6 months |

| McQueen et al, 201440 United States 1 site |

Retrospective cohort Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time or Dexcom device | 2006–2011 | ≥ 18 | Type 1 diabetes | NR | NR | Not pregnant | 66/67 | CGM with SMBG | SMBG | Up to 10 months |

| Olivier et al, 201434 Canada 2 sites |

Pilot RCT Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | February 2009–January 2011 | 5–18 | Type1 diabetes ≥ 1 year | NR | Injection therapy | NA | 10/10 | CGM with CSII | CSII with delayed CGM | 4 months |

| Quiros et al, 201541 Europe 8 sites |

Retrospective observational study of RCT (SWITCH) Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | January 2008–July 2010 | 6–70 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 1 year | A1C between 7.5% and 9.5% | CSII > 6 months | NA | 20 (total sample size) | SAP | CSII | 3 years |

| Radermecker et al, 201042 Belgium 1 site |

Prospective observational controlled trial Medtronic Guardian REAL-Time | NR | Adults | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 1 year | ≥ 6 capillary glucose recordings of < 60 mg/dL in 14 days | CSII > 1 year | NA | 13 (total sample size) | CGM | SMBG | 12 weeks |

| Rosenlund et al, 201535 Denmark 2 sites |

RCT Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm Veo | February 2012–December 2014 | 18–75 | Type 1 diabetes | A1C ≥ 7.5% | MDI | GFR at least 45 mL/min/ 1.73 m2 No other concomitant disease; no pregnancy | 26/29 | SAP | MDI with SMBG | 1 year |

| Rubin and Peyrot, 201236 United States and Canada 30 sites |

RCT (STAR 3) Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | January 2007–December 2008 | 7–70 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 3 months | A1C between 7.4% and 9.5% | MDI | < 2 hypoglycemic events in previous year Not pregnant | 243/238 | SAP | MDI with SMBG | 1 year |

| Slover et al, 201237 United States and Canada 30 sites |

RCT (STAR 3) Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm REAL-Time | January 2007–December 2008 | 7–18 | Type 1 diabetes ≥ 3 months | A1C between 7.4% and 9.5% | MDI | < 2 hypoglycemic events in previous year | 78/78 | SAP | MDI with SMBG | 1 year |

| Soupal et al, 201643 Czech Republic 1 site |

Prospective controlled trial Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm Veo | NR | > 18 | Type 1 diabetes > 2 years | A1C between 7% and 10% | MDI or CSII | No concomitant disease; not pregnant or planning pregnancy | 27/38 | SAP CGM with MDI | SMBG with CSII SMBG with MDI | 52 weeks |

| Tumminia et al, 201538 Italy 1 site |

RCT, crossover Medtronic MiniMed Guardian REAL-Time | January–March 2012 | 18–60 | Type 1 diabetes | A1C > 8% | MDI or CSII | Middle-class socioeconomic status; no concomitant disease; not pregnant or planning pregnancy | 20 (total sample size) | CGM | SMBG | 14 months; 6 months of intervention, 2 months of washout before crossover |

| van Beers et al, 201639 Netherlands 2 sites |

RCT (IN CONTROL) Medtronic MiniMed Paradigm Veo | March 2013–February 2014 | 18–75 | Type 1 diabetes | Impaired hypoglycemia awareness | CSII or MDI | No concomitant disease; not pregnant | 26/26 | CGM | SMBG | 44 weeks; 16 weeks of intervention, 12 weeks of washout before crossover |

Abbreviations: A1C, glycated hemoglobin; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (insulin pump); GFR, glomerular filtration rate; I/C, intervention/control; MDI, multiple daily injections; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SAP, sensor-augmented pump; SMBG, self-management of blood glucose.

Some studies have been given a trial nickname; where that exists, it has been listed to help identify multiple publications on the same study.

Number of sites not provided.

Results for Time-Related Glucose Variability

We examined glucose variability as a measure of time spent in or out of the target glycemic (normoglycemic) range. Results for time spent in the target glycemic range are presented in Table 4. Results from two randomized controlled trials favoured continuous glucose monitoring over control.

Table 4:

Results for Time Spent in Target Glycemic Range

| Author, Year | Measure of Glucose Variability | Resultsa | Differencea | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| Adult Population, RCTs | |||||

| Beck et al, 201724 | Mean minutes per day within the target range of 70–180 mg/dL | 736 (SE 7.59) Change from baseline: | 650 (SE 7.61) Change from baseline: 0 min | Adjusted mean difference: 77 (99% CI 6–147) | .005 |

| van Beers et al, 201639 | Mean % time spent in normoglycemia (4.0–10.0 mmol/L) | +76 min 65.0 (95% CI 62.8–67.3) | 55.4 (95% CI 53.1–57.7) | 9.6 (95% CI 8.0–11.2) | < .01 |

| Adult Population, Observational Study | |||||

| Soupal et al, 201643 | Mean % time spent between 4.0 and 10.0 mmol/L | 69 (SE 2.12) | 59 (SE 2.46) | 10 (95% CI 6.75–13.25) | Study authors reported difference as not significantb |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SE, standard error.

CIs, P-values, and SE were calculated by the authors of this health technology assessment.

Repeated calculations conducted by the authors of this health technology assessment yielded a significant P-value.

The quality of the evidence for time spent in the target glycemic range was moderate for the randomized controlled trials and very low for the observational study. Details of the GRADE assessment can be found in Appendix 2.

Table 5 summarizes the findings for studies that evaluated time spent outside the target glycemic range. Overall, results favoured continuous glucose monitoring over control.

Table 5:

Results for Time Spent Outside of Target Glycemic Range

| Author, Year | Measure of Glucose Variability | Results | Difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| Time Spent in Hypoglycemic Range, Adult Population, RCTs | |||||

| Beck et al, 201724a | Median minutes per day in hypoglycemia (< 60 mg/dL) | 20 (IQR 9–30) | 40 (IQR 16–68) | −20 | .002b |

| Hermanides et al, 201127 | Mean % of time in hypoglycemia (< 4.0 mmol/L) | 2.7 (SE 0.53) | 2.5 (SE 0.6) | LSM difference at baseline and end of study: 0.2 (95% CI −1.6 to 1.7) | .96 |

| Ly et al, 201333a | Median % of time in hypoglycemia (< 60 mg/dL) | Dayc: 1.5 (IQR 0.9–3.7) Nightc: 2.4 (IQR 0.4–5.3) | Dayc: 3.3 (IQR 1.6–5.9) Nightc: 6.2 (IQR 4.2–9.9) | Dayc: −1.8 Nightc: −3.8 | Dayc: .01b Nightc: < .001b |

| van Beers et al, 201639a | Mean hours per day in hypoglycemia (≤ 3.9 mmol/L) | 1.6 (95% CI 1.3–2.0) | 2.7 (95% CI 2.4–3.1) | Mean difference −1.1 (95% CI −1.4 to −0.8) | < .001 |

| Time Spent in Hyperglycemic Range, Adult Population, RCTs | |||||

| Beck et al, 201724a | Median minutes per day in hyperglycemia (> 250 mg/dL) | 223 (IQR 128–383) | 347 (IQR 241–429) | −124 | < .001b |

| Hermanides et al, 201127 | Mean % of time in hyperglycemia (> 11.1 mmol/L) | 21.6 (SE 1.91) | 38.2 (SE 3.58) | LSM difference between groups at baseline and end of study: −17.3 (95% CI −25.1 to −9.5) | < .001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range; LSM, least square mean; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SE, standard error.

Select results are presented; additional thresholds and permutations of similar results are available in the original study.

Authors reported the P-value for the mean difference; the comparison is for the median difference.

Day, 6 a.m. to 10 p.m.; night, 10 p.m. to 6 a.m.

The quality of the evidence for time spent outside the target glycemic range was moderate for the randomized controlled trials in adults. Details of the GRADE assessment can be found in Appendix 2.

Results for Hypoglycemia

Table 6 summarizes the results for hypoglycemia and severe hypoglycemia. Because of variations in how hypoglycemia was reported between studies, it was difficult to develop a summary conclusion. However, in general there did not seem to be a substantial difference in hypoglycemic outcomes between the continuous glucose monitoring groups and the control groups in both adult and pediatric populations.

Table 6:

Results for Hypoglycemia

| Author, Year | Measure of Hypoglycemia | Results | Difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| Adult Population, RCTs | |||||

| Bergenstal et al, 201025 | AUC of rate of patients having blood glucose < 50 mg/dL per day | 0.02 (SE 0.03)a | 0.03 (SE 0.07)a | −0.01 (SE 0.003)a | .16b |

| Hermanides et al, 201127 | Mean number of hypoglycemic episodes (< 4.0 mmol/L) per day | 0.7 (SE 0.11)a | 0.6 (SE 0.12)a | 0.1 (95% CI −0.2 to 0.5)a | .40 |

| Langeland et al, 201230 | Mean number of hypoglycemic episodes (≤ 3.1 mmol/L) per 4 weeks | 8.2 (SE 0.41)a | 7.3 (SE 0.36)a | 0.9 (95% CI 0.85–0.95)a | .67c |

| Tumminia et al, 201538 | AUC of rate of patients having blood glucose < 70 mg/dL per day | Owing to concerns with the statistical analyses, results are not reportedd | NS | ||

| Adult Population, Observational Studies | |||||

| Radermecker et al, 201042 | Mean decrease from baseline in number of hypoglycemic episodes (< 60 mg/dL) per 14 days | 6.2 (95% CI 2.2–10.2) | 0.67 (95% CI −4.7 to 6.0) | Mean difference 5.3 (95% CI −0.49 to 11.55)a | .85a |

| Soupal et al, 201643 | Mean reduction of % time spent in hypoglycemia | 6 (SE 0.87)a | 7 (SE 1.18)a,e | −1 (SE 2.39)d | .68 |

| Pediatric Population, RCTs | |||||

| Bergenstal et al, 201025 | AUC of rate of patients having blood glucose < 50 mg/dL | Owing to concerns with the statistical analyses, results are not reportedd | .64 | ||

| Bukara-Radujkovic et al, 201126 | Difference in average number of hypoglycemic episodes (< 3.5 mmol/L) per day | 0.223 | 0.175 | 0.048 | NR |

| Slover et al, 201137 | AUC of rate of patients having blood glucose < 60 mg/dL per day (change from baseline)e | Age 7–12: 0.05 (SD 0.08) Age 13–18: −0.05 (SD 0.08) | Age 7–12: 0.03 (SD 0.06) Age 13–18: −0.05 (SD 0.09) | Age 7–12: 0.02 (SD 0.16) Age 13–18: 0 (SD 0.15) | Age 7–12: .05 Age 13–18: .87 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; NR, not reported; NS, not significant; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error.

Calculations for SE and CI were conducted by the authors of this health technology assessment.

The reported P-value was adjusted for baseline differences, but the SE is for the unadjusted difference.

We could not replicate results for this P-value based on the methods and data reported by the authors.

Data were skewed, but the authors used statistical methods that are valid only under a symmetric assumption. Statistical results were questionable.

The study included both patients on insulin pumps and those on multiple daily injections, but these results were for only patients on multiple daily injections.

The quality of the evidence for hypoglycemia was low for the randomized controlled trials in adults, and very low for the observational studies in adults and randomized controlled trials in children. Details of the GRADE assessment can be found in Appendix 2.

Table 7 summarizes findings for severe hypoglycemic events. Results were generally in favour of continuous glucose monitoring.

Table 7:

Results for Severe Hypoglycemic Events

| Author, Year | Measure of Severe Hypoglycemic Events | Results | Difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| Adult Population, RCTs | |||||

| Little et al, 201432 | Severe hypoglycemia requiring the assistance of another person, annualized rate | 0.8 (SD 1.8) | 0.9 (SD 2.1) | −0.1 (SD 3.63) | .95 |

| Ly et al, 201333a | Severe hypoglycemia, including seizure or coma, 6-month rate per 100 patient-months (change from baseline) | −1.8 | 0.1 | −1.5 (95% CI −2.7 to −0.3)a | .02b |

| van Beers et al, 201639 | Number of severe hypoglycemic events | 14 | 34 | −20 | .033b |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation.

Results generated from a statistical model.

Computed using a nonparametric statistical test.

The quality of the evidence for severe hypoglycemic events was low for the randomized controlled trials in adults. Details of the GRADE assessment can be found in Appendix 2.

Results for A1C Levels

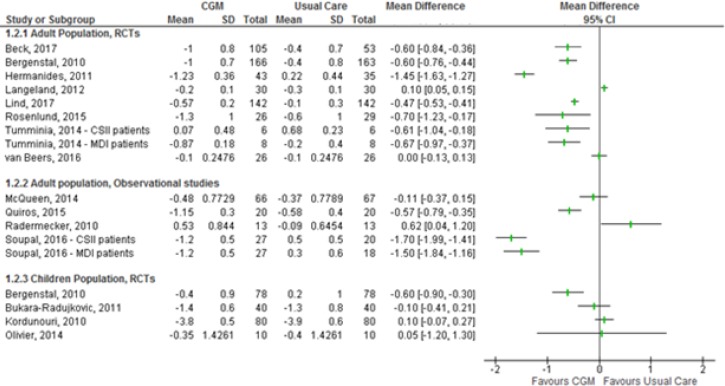

Studies comparing average A1C levels reported results in two ways: change in average A1C levels from baseline, and average A1C levels at the end of the study. The former approach accounts for baseline differences in A1C levels; as a result, our assessment focused only on results derived using this approach. Results for the difference in change in blood glucose levels from baseline to end of study are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Changes in A1C from Baseline to End of Study.

Sources: Data from Beck et al,24 Bergenstal et al,25 Bukara-Radujkovic et al,26 Hermanides et al,27 Kordonouri et al,29 Langeland et al,30 Lind et al,31 McQueen et al,40 Olivier et al,34 Quiros et al,41 Radermecker et al,42 Rosenlund et al,35 Soupal et al,43 Tumminia et al,38 and van Beers et al.39

Abbreviations: A1C, glycated hemoglobin; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CI, confidence interval; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (insulin pump); MDI, multiple daily injections; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SD, standard deviation.

Note: Olivier et al34 and Quiros et al41 reported results for a combined population of adults and children. Tumminia et al38 reported a crossover design, but their analysis was based on a before-after design.

Based on the overall results, continuous glucose monitoring led to a greater reduction in A1C levels than usual care. However, the average A1C values at the end of follow-up were higher than 7% for all studies—above the threshold set by the Diabetes Canada guidelines.6 As a result, we do not regard the reduction in A1C observed above as clinically important. However, Beck et al24 reported that 18% of people who used continuous glucose monitoring achieved an A1C ≤ 7.0%; only 2% of the usual care group reached this threshold.

The quality of the evidence for changes in A1C levels was moderate for randomized controlled trials in adults, low for randomized controlled trials in children, and very low for observational studies in adults. Details of the GRADE assessment can be found in Appendix 2.

Results for User Satisfaction

Of the studies that reported user satisfaction, most used well-known measures of quality of life, often measures specific to diabetes. Table 8 presents results reported in the individual studies.

Table 8:

Results for User Satisfaction

| Author, Year | Measure of User Satisfaction | Results | Difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| Results for Adult Population, RCTs | |||||

| Beck et al, 201724 | CGM satisfaction survey, mean score | 4.2 (SD 0.4) | NR | NR | NR |

| Hermanides et al, 201127 | Problem areas in diabetes scale | 21.0 (SD 19.3) | 23.7 (SD 19.4) | LSM change from baseline: −7.9 (95% CI −15.1 to −0.61) | .03 |

| Hypoglycemia fear survey | 24.1 (SD 20.2) | 20.3 (SD 16.9) | LSM change from baseline: −3.2 (95% CI −10.0 to 3.7) | .36 | |

| DTSQ | 32.4 (SD 3.5) | 23.8 (SD 6.2) | LSM change from baseline: 9.3 (95% CI 7.3–11.3) | < .001 | |

| Hommel et al, 201428 | DTSQ status version, overall treatment satisfaction | NR | NR | 1.16 | .010 |

| Langeland et al, 201230 | DTSQ change version, change in total score SF-36, change in total average | 3.93 (SD 8.00) −0.3 (SD 8.5) | 5.74 (SD 5.83) −0.3 (SD 9.8) | −1.81 (SD 16.14)a 0 (SD 16.14)a | .47 .35 |

| Lind et al, 201731 | DTSQ status version, scale total | 30.21 (95% CI 29.47–30.96) | 26.62 (95% CI 25.61–27.64) | 3.43 (95% CI 2.31–4.54) | < .001 |

| Little et al, 201432 | DTSQ total satisfaction | 30 (SD 5) | 30 (SD 5) | — | .79 |

| Rubin and Peyrot, 201236 | SF-36, change from baseline | MCS: 0.05 PCS: 1.22 | MCS: −1.26 PCS: 0.26 | MCS: −1.21a PCS: 0.96a | NR NR |

| Results for Adult Population, Observational Studies | |||||

| Radermecker et al, 201042 | DQOL total score, change from baseline | −2.3 (95% CI −6.4 to 1.7) | 0.7 (95% CI −2.5 to 3.8) | −3.0 (95% CI −7.67 to 1.68)a | .22a |

| Results for Pediatric Population, RCTs | |||||

| Hommel et al, 201428 | PedsQL overall health-related quality of life | NR | NR | Child self-rating: −0.31 (SD 0.84) Parent proxy rating: −3.92 (SD 1.18)b | Child self-rating: .84 Parent proxy rating: .002 |

| Kordonouri et al, 201229 | KIDSCREEN-27 psychological well-being | Child self-report: 50.4 (SD 9.2) Proxy/parent: 47.8 (SD 9.3) | Child self-report: 50.3 (SD 10.8) Proxy/parent: 48.6 (SD 10.3) | Child self-report: 0.1 (SD 18.56)a Proxy/parent: −0.8 (SD 18.74)a | Child self-report: .905 Proxy/parent: .826 |

| Olivier et al, 201434 | DTSQ change in total score | NR | NR | −9 (95% CI −16 to −1) | .02 |

| Rubin and Peyrot, 201236 | PedsQL overall score, change from baseline | Child self-report: 0.33 Caregiver: 40.19 | Child self-report: 1.19 Caregiver: 5.07 | Child self-report: 29.14 Caregiver: 35.12 | Child self-report: .001 Caregiver: < .001 |

Abbreviations: CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CI, confidence interval; DQOL, Diabetes Quality of Life [questionnaire]; DTSQ, Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire; LSM, least square mean; MCS, mental composite score; NR, not reported; PCS, physical composite score; PedsQL, pediatric quality of life inventory; RCT, randomized controlled trials; SD, standard deviation; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

Results calculated based on information published in original studies.

Publication noted that this was not a clinically meaningful difference.

Results were inconsistent across studies, probably reflecting differences in types of outcomes and survey tools. Therefore, we rated the quality of the evidence for user satisfaction as low for randomized controlled trials in adults and children, and very low in observational studies in adults. Details of the GRADE assessment can be found in Appendix 2.

Summary

We included 20 studies that reported on the use of continuous glucose monitors (as standalone devices or integrated with insulin pumps) compared with usual care. Usual care was typically defined as self-monitoring of blood glucose levels using a finger-prick blood glucose meter.

We did not perform meta-analyses because of the heterogeneity of populations and interventions. All results for outcomes of interest have been summarized narratively (Table 9).

Table 9:

Summary of Findings

| Outcome | Finding | GRADE |

|---|---|---|

| Time-related glucose variability | Continuous glucose monitoring was more effective than usual care in terms of increased time spent in the target glycemic range | Moderate to very low |

| Continuous glucose monitoring was more effective than usual care in terms of decreasing time spent outside the target glycemic range | Moderate | |

| Hypoglycemia | There was no substantial difference in hypoglycemic outcomes between patients in the continuous glucose monitoring group and those in the usual care group | Low to very low |

| Continuous glucose monitoring was more effective than usual care in reducing severe hypoglycemic events | Low | |

| A1C levels | Results favoured continuous glucose monitoring over usual care in the reduction of A1C levels from baseline | Moderate to very low |

| User satisfaction | Findings on end-of-study user satisfaction with continuous glucose monitoring compared with usual care were inconsistent | Low to very low |

| Findings on children, parent, and caregiver satisfaction with continuous glucose monitoring compared with usual care were inconsistent | Low |

Abbreviations: A1C, glycated hemoglobin; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation.

We applied the GRADE criteria to assess the quality of evidence (Appendix 2).19 We applied GRADE to randomized controlled trials in adult populations, observational studies in adult populations, and randomized controlled trials of child populations separately for each outcome, where reported. There were no observational studies in child populations.

Discussion

Main Findings and Clinical Relevance

Continuous glucose monitoring was more effective than self-monitoring of blood glucose for the management of type 1 diabetes, as demonstrated by outcomes such as time spent in target glucose range and severe hypoglycemic events. Interestingly, the majority of the reviewed studies were unable to demonstrate the same effect for hypoglycemia.

Studies evaluating the impact of continuous glucose monitoring on user satisfaction yielded mixed results. These findings may be partly explained by the fact that wearing a sensor or a pump may be perceived as an interruption to children's normal activities. Engaging with parents, caregivers, and children to understand the most practical way to monitor blood glucose is important for effective management of type 1 diabetes. In addition, to avoid diabetes complications, controlling diabetes at a younger age can reduce the risk of metabolic memory,44 a condition characterized by persistent diabetes complications despite tight glucose control. Details about parent and child preferences with regard to diabetes management in the Ontario context are provided in the Patient, Caregiver, and Public Engagement section of this health technology assessment.

We noted several limitations from the primary studies. First, studies that evaluated the effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in reducing hyperglycemia recruited patients with high A1C levels. A substantial decrease in A1C would have been required from the patients in these studies to meet the 7% threshold recommended by many experts and clinical practice guidelines. Although the majority of studies did demonstrate a reduction in A1C, the average decrease was not enough to meet the threshold. Second, some studies expressed concerns about missing data.28,36,37 To address the problem, these studies imputed outcomes by carrying forward the observation from the last visit, but treated the imputed values as if they were real during analysis. In doing so, these studies may have overestimated the precision of point estimates and introduced outcome classification errors. Third, the statistical methods used in some studies25,32,38 yielded estimates with ranges that covered implausible values. Specifically, the reported standard deviations were larger than the point estimates, suggesting that the area under the curve or the number of hypoglycemic episodes could be negative. As a result, we could not determine the true precision of the point estimates for these studies. Finally, the definition of usual care for some studies included the use of an insulin pump, a mode of insulin administration that is used less in Ontario (there are about 14,000 insulin pump users in Ontario). This means results from these studies may not accurately reflect the effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring in Ontario, where usual care generally involves multiple daily injections. A comparison of different methods of insulin administration was beyond the scope of this health technology assessment.

Real-World Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring

Some studies29,31,35,39 enrolled only patients who exceeded a certain threshold of adherence with glucose monitoring; as a result, the level of adherence in the controlled setting of these studies was likely to be higher than in the general population. Several survey studies have examined adherence and reasons for discontinuation of continuous glucose monitoring in the real world.45–49 They demonstrated that patients do not use continuous glucose monitoring 100% of the time, and that use tends to taper off over time. The main reasons reported for discontinued use were cost; discomfort with wearing the devices, including sensors falling off; and finding the alarms disruptive.

Ongoing Studies

During scoping, we identified 35 studies on clinicaltrials.gov related to continuous glucose monitoring, glycemic control, and type 1 diabetes. However, we determined that the current literature was sufficient to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring.

Conclusions

Based on moderate certainty in the evidence, we found that continuous glucose monitoring was more effective than self-monitoring of blood glucose in managing type 1 diabetes for some outcomes, such as time spent in target glucose range and time spent outside target glucose range. Similar findings were obtained for the outcome of severe hypoglycemic events, although there was low certainty in the evidence for this outcome.

ECONOMIC EVIDENCE

Research Question

What is the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose in patients with type 1 diabetes?

Methods

Economic Literature Search

We performed an economic literature search on January 25, 2017, for studies published from January 1, 2010, to the search date. We applied methodological filters to the clinical search to limit retrieval to economic evaluations and studies on cost, quality of life, and health utilities.50

Database auto-alerts were created in MEDLINE, Embase, and CINAHL and monitored for the duration of the health technology assessment review. We performed targeted grey literature searching of health technology assessment agency sites, clinical trial registries, and Tufts Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry. See Clinical Evidence, Literature Search, above, for further details on methods used. See Appendix 1 for literature search strategies, including all search terms.

Finally, we reviewed reference lists of included economic literature for any additional relevant studies not identified through the systematic search.

Literature Screening

A single reviewer reviewed titles and abstracts, and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, we obtained full-text articles. For studies containing several comparators, we extracted only the results for the comparison of interest.

Types of Studies

We included cost-effectiveness or cost-utility analyses that compared continuous glucose monitoring with self-monitoring of blood glucose in adults and children with type 1 diabetes. We examined economic studies that fulfilled the described entry criteria and that had a follow-up time or time horizon of 1 year or greater.

We did not include abstracts, letters, editorials, unpublished studies, or noncomparative studies reporting the costs of continuous glucose monitoring.

Types of Participants

The population of interest was patients with type 1 diabetes, including those with hypoglycemia unawareness.

Types of Interventions

Continuous glucose monitoring can be performed using different devices and technologies (see Background). We looked at studies that compared self-monitoring of blood glucose plus either multiple daily injections or an insulin pump with one or more continuous glucose monitoring interventions:

Continuous glucose monitoring plus multiple daily injections

Continuous glucose monitoring plus insulin pump

Sensor-augmented pump (continuous glucose monitoring integrated with an insulin pump)

Sensor-augmented pump with a low-glucose suspend feature

Types of Outcomes Measures

We examined the following outcomes: incremental costs, incremental quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), and incremental net benefit.

Data Extraction

We extracted relevant data on the following:

Source (i.e., name, location, year)

Populations and comparators

Interventions

Outcomes (i.e., health outcomes, costs, and ICERs)

Study Applicability and Limitations

We determined the usefulness of each identified study for decision-making by applying a modified applicability checklist for economic evaluations that was originally developed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom. The original checklist is used to inform development of the institute's clinical guidelines. We modified the wording of the questions to remove references to guidelines and to make them Ontario-specific.

We separated the checklist into two sections. In the first, we assessed the applicability of the study to our research question. A summary of the studies judged to be directly applicable, partially applicable, or not applicable to the research question are shown in Appendix 3. If the study was deemed directly or partially applicable to the research question, we assessed the limitations of the study (minor, potentially serious, or very serious) using the second section of the checklist.

Results

Literature Search

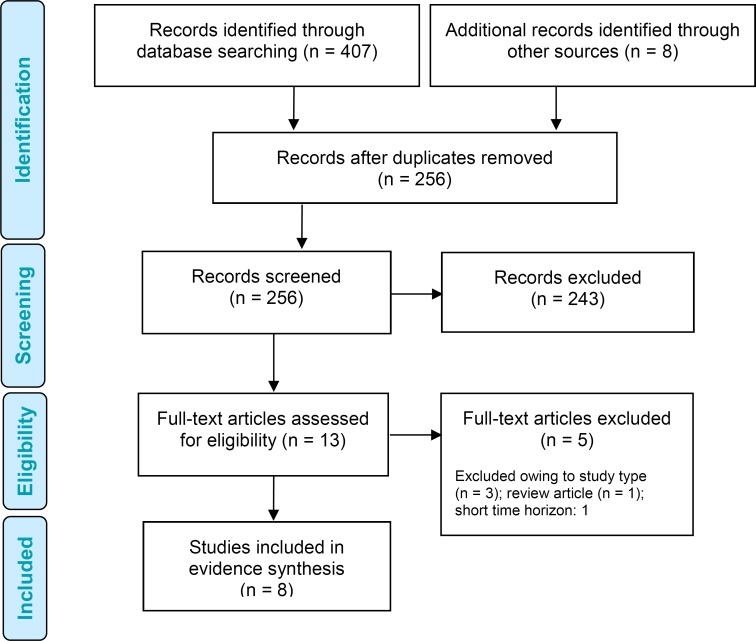

The literature search yielded 256 citations published between January 1, 2010, and January 25, 2017 (with duplicates removed). We excluded a total of 243 articles based on information in the title and abstract. We then obtained the full texts of 13 potentially relevant articles for further assessment. Figure 3 presents the flow diagram for the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA).

Figure 3: PRISMA Flow Diagram—Economic Search Strategy.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al.23

Eight studies (seven cost-utility analyses51–57 and one health technology assessment report by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence58) met the inclusion criteria (Table 10). All studies were based on models. Three cost-utility analyses studies were from United States,51,52,57 two studies were from the United Kingdom,53,58 and one each was from Sweden,54 France,55 and Denmark.56 No studies were done in children with type 1 diabetes.

Table 10:

Results of the Economic Literature Review—Summary

| Name, Year, Location | Study Design and Perspective | Population | Intervention/ Comparator | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health Outcomes | Costs | Cost-Effectiveness | ||||

| Huang et al, 2010,57 United States |

|

Cohort 1: adults with T1D aged ≥ 25 years and A1C ≥ 7.0% Cohort 2: all ages with A1C ≤ 7.0% | CGM SMBG | Cohort 1 Total QALYs: SMBG 13.75; CGM 14.35 QALYs gained: 0.60 Cohort 2 Total QALYs: SMBG 16.69; CGM 17.80 QALYs gained: 1.11 Annual discount rate: 3% | 2007 US dollars Cohort 1 Total costs: SMBG $601,070; CGM $659,837 Incremental cost for CGM: $58,767 vs. SMBG Cohort 2 Total costs: SMBG $2,111,539; CGM $2,198,925 Incremental cost for CGM: $87,386 vs. SMBG Annual discount rate: 3% | Cohort 1 ICER: $98,679 per QALY gained vs. SMBG Cohort 2 ICER: $87,386 per QALY gained vs. SMBG |

| Kamble et al, 2012,52 United States |

|

Adults with inadequately controlled T1D; mean age of 41.3 years; mean A1C 8.3% | SAP SMBG MDI | Total QALYs: SAP 10.794; SMBG MDI 10.418 QALYs gained: 0.376 Annual discount rate: 3% | 2010 US dollars 3-day sensors Total costs: SMBG MDI $167,170; SAP $253,493 Incremental cost for SAP: $86,324 vs. SMBG MDI 6-day sensors Total costs: SMBG MDI $167,170; SAP $230,352 Incremental cost for SAP: $63,182 vs. SMBG MDI Annual discount rate: 3% | 3-day sensors ICER: $229,675 per QALY gained vs. SMBG MDI 6-day sensors ICER: $168,104 per QALY gained vs. SMBG MDI |

| McQueen et al, 2011,51 United States |

|

20-year history of T1D, mean age of 40 years | CGM + SMBG with intensive insulin therapy SMBG with intensive insulin therapy | Total QALYs: SMBG 10.289; CGM + SMBG 10.812 QALYs gained: 0.52 Annual discount rate: 3% | 2007 US dollars Total costs: SMBG $470,583; CGM + SMBG $494,135 Incremental cost for CGM + SMBG: $23,552 vs. SMBG alone Annual discount rate: 3% | ICER: $45,033 per QALY gained vs. SMBG alone |

| Riemsma et al, 2016,58 United Kingdom |

|

27-year history of T1D; mean age of 42 years; 38% male | SAP SMBG MDI or SMBG CSII | SAP vs. SMBG MDI Total QALYs: SMBG MDI 11.4146; SAP 12.0604 QALYs gained: 0.6458 SAP vs. SMBG CSII Total QALYs: SMBG CSII 11.9756; SAP 12.0604 QALYs gained: 0.0849 Annual discount rate: 1.5% | 2014 British pounds SAP vs. SMBG MDI Total costs: SMBG MDI £61,070; SAP £147,150 Incremental cost for SAP: £86,100 vs. SMBG MDI SAP vs. SMBG CSII Total costs: SMBG CSII £90,436; SAP £147,150 Incremental cost for SAP: £56,713 vs. SMBG CSII Annual discount rate: 3.5% | SAP vs. SMBG MDI ICER: £133,323 per QALY vs. SMBG MDI SAP vs. SMBG CSII ICER: £668,789 per QALY vs. SMBG CSII |

| Roze et al, 2016,53 France |

|

Patients with T1D; mean age 27 years; mean duration of diabetes 13 years; mean A1C 10% | SAP LGS SMBG CSII | Total QALYs: SAP LGS 17.88; SMBG CSII 14.89 QALYs gained: 2.99 Annual discount rate: 1.5% | 2013 British pounds Total costs: SAP LGS £125,559; SMBG CSII £88,991 Incremental cost for SAP LGS: £36,568 vs. SMBG CSII Annual discount rate: 3.5% | ICER: £12,233 per QALY gained vs. SMBG CSII |

| Roze et al, 2015,54 France |

|

Patients with T1D; mean age 27 years; mean duration of diabetes 13 years; mean A1C 8.6% | SAP SMPG CSII | Total QALYs: SAP 13.05; SMPG CSII 12.29 QALYs gained: 0.76 Annual discount rate: 3% | 2013 Swedish kronor (SEK) Total costs: SAP SEK 868,897; SMPG CSII SEK 453,791 Incremental cost for SAP: SEK 415,106 vs. SMPG CSII Annual discount rate: 3% | ICER: SEK 60,332 per QALY gained vs. SMPG CSII |

| Roze et al, 2016,55 France |

|

Patients with T1D; mean age 36 years; mean duration of diabetes 17 years; mean A1C 9.0% | SAP LGS SMBG CSII | Uncontrolled A1C at baseline Total QALYs: SAP LGS 10.55; SMBG CSII 9.36 QALYs gained: 1.19 Elevated risk for hypoglycemic events Total QALYs: SAP LGS 18.46; SMBG CSII 18.30 QALYs gained: 2.99 Annual discount rate: 4% | 2014 euros Uncontrolled A1C at baseline Total costs: SAP LGS ζ84,972; SMBG CSII ζ49,171 Incremental cost for SAP LGS: ζ35,801 vs. SMBG CSII Elevated risk for hypoglycemic events Total costs: SAP LGS ζ88,680; SMBG CSII ζ57,097 Incremental cost for SAP LGS: ζ31,583 vs. SMBG CSII Annual discount rate: 4% | Uncontrolled A1C at baseline ICER: ζ30,163 per QALY gained vs. SMBG CSII Elevated risk for hypoglycemic events ICER: ζ22,005 per QALY gained vs. SMBG CSII |

| Roze et al, 2017,56 France |

|

Cohort 1: people with T1D and hyperglycemia (baseline A1C 8.1%) Cohort 2: people with T1D at increased risk for hypoglycemic events (owing to impaired awareness of hypoglycemia) | SAP LGS SMBG CSII | Cohort 1 Total QALYs: SAP LGS 12.44; SMBG CSII 10.99 QALYs gained: 1.45 Cohort 2 Total QALYs: SAP LGS 13.08; SMBG CSII 11.20 QALYs gained: 1.88 Annual discount rate: 3% | 2015 Danish kroner (DKK) Cohort 1 Total costs: SAP LGS DKK 2,027,316; SMBG CSII DKK 1,801,293 Incremental cost for SAP LGS: DKK 226,023 vs. SMBG CSII Cohort 2 Total costs: SAP LGS DKK 2,277,868; SMBG CSII DKK 2,109,186 Incremental cost for SAP LGS: DKK 168,682 vs. SMBG CSII Annual discount rate: 3% | Cohort 1 ICER: DKK 156,082 per QALY gained vs. SMBG CSII Cohort 2 ICER: DKK 89,868 per QALY gained vs. SMBG CSII |

Abbreviations: A1C, glycated hemoglobin; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (insulin pump); ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; LGS, low-glucose suspend [feature]; MDI, multiple daily injections; NHS, National Health Service; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; SAP, sensor-augmented pump; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose; SMPG, self-monitoring of plasma glucose; T1D, type 1 diabetes.

We excluded five studies: one review of the economic literature,59 one study with a 6-month time horizon,60 and three costing studies.61–63 The costing studies were focused on the costs of self-monitoring of blood glucose only, the implications of averting severe hypoglycemic events, and patient time spent on diabetes-related care.

Review of Included Economic Studies

Applicability and Limitations of the Included Studies

We assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using an applicability checklist (Appendix 3).

All studies were deemed partially applicable to our research question, because they were partially similar to our base case population and comparators. However, we found no studies that evaluated continuous glucose monitoring from the perspective of Ontario's public health care payer, so the results could not be directly translated to the Ontario context.

All studies included important outcomes related to continuous glucose monitoring and insulin infusion. All studies except those by McQueen et al51 and Riemsma et al58 were sponsored by device manufacturers.

All eight studies had important limitations, including the estimation of transition probabilities and treatment effects from various study populations. Also, they did not fully capture hypoglycemic events and two did not specify the use of insulin infusion. The majority of the studies used the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation model, which was based on the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial64 and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study,65 and was developed to reflect the natural history of type 1 diabetes.

Discussion

Of the eight eligible studies:

Three compared continuous glucose monitoring plus a sensor-augmented pump with self-monitoring of blood glucose plus either multiple daily injections52,58 or insulin pump therapy54,58

Three compared continuous glucose monitoring plus a low-glucose suspend feature with self-monitoring of blood glucose plus insulin pump therapy53,55,56

McQueen et al51 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring plus self-monitoring of blood glucose versus self-monitoring of blood glucose alone. Both interventions were accompanied by intensive insulin therapy. Inputs to their economic model were obtained mainly from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial,64 the UK Prospective Diabetes Study,65 and the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy.66

Huang et al57 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring versus self-monitoring of blood glucose. The authors based their effectiveness data on the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation continuous glucose monitoring trials67–69 and the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial,64 and they took information on diabetes complications from a modelling study of type 2 diabetes.70 The authors concluded that continuous glucose monitoring was cost-effective for an adult population aged ≥ 25 years with A1C levels ≥ 7.0%, assuming a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000 USD/QALY gained. Continuous glucose monitoring was more cost-effective for all age groups with A1C levels ≤ 7.0%.57 They found that if the benefits of continuous glucose monitoring were not extended long-term, the ICER would exceed $700,000 USD/QALY gained and would not be cost-effective at commonly used thresholds.

Riemsma et al58 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of several technologies, including continuous glucose monitoring integrated with a sensor-augmented pump; self-monitoring of blood glucose plus multiple daily injections; and self-monitoring of blood glucose plus an insulin pump. They obtained short-term effectiveness data on continuous glucose monitoring from a meta-analysis of 19 clinical trials and long-term effectiveness data from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial,64 the UK Prospective Diabetes Study,65 and other literature sources (this meta-analysis was not applicable to the clinical evidence review in this health technology assessment). The authors found that continuous glucose monitoring with a sensor-augmented pump was not cost-effective compared to self-monitoring of blood glucose plus either multiple daily injections or an insulin pump. The study assumed treatment effects to be the mean reduction in A1C from baseline to 12 months. The report concluded that self-monitoring of blood glucose plus multiple daily injections was the most cost-effective option, given the current United Kingdom threshold of £30,000 GBP/QALY gained.58

Kamble et al52 evaluated the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring plus a sensor-augmented pump compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose plus multiple daily injections. The authors derived the efficacy of continuous glucose monitoring with a sensor-augmented pump from the STAR 3 adult cohort.25 They found that continuous glucose monitoring with a sensor-augmented pump did not represent good value for money in adults when considering (1) the significant and ongoing costs associated with continuous glucose monitoring; and (2) the costs of long-term complications in relation to the expected health benefits of 0.376 QALYs.

Roze et al evaluated the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring compared with self-monitoring of plasma glucose plus insulin pump therapy. They performed four studies, from the perspectives of the United Kingdom,53 Sweden,54 France,55 and Denmark.56 All but one54 used continuous glucose monitoring with a low-glucose suspend feature. The authors used the Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation diabetes model to determine the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring over a lifetime horizon. They derived the clinical effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring from a patient-level meta-analysis71 and a Swedish observational study on type 2 diabetes.72 Overall, the conclusion from all four economic evaluations was that continuous glucose monitoring was likely to be cost-effective compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose and insulin pump therapy.

Overall, the results from the economic evidence review were mixed. McQueen et al51 demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring versus self-monitoring of blood glucose (when both interventions were accompanied by intensive insulin therapy, type not specified) at an empirical threshold of $50,000 USD/QALY gained. However, the authors may have modelled a constant decreasing rate of complications from the start of continuous glucose monitoring to approximately 33 years, resulting in relatively favourable ICER values.

Huang et al57 also demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring versus self-monitoring of blood glucose, but for a much higher empirical threshold of $100,000 USD/QALY gained, which might not be applicable to Canadian settings. As well, the authors did not specify the method of insulin infusion and found considerable uncertainties around the ICER.

Economic evaluations by Roze et al also demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring with a low-glucose suspend feature versus self-monitoring of blood glucose and insulin pump from the perspectives of the United Kingdom,53 Sweden,54 France,55 and Denmark.56

In contrast, Riemsma et al58 showed that newer technologies—standalone continuous glucose monitoring and sensor-augmented pumps—were not cost-effective compared with the current standard of self-monitoring of blood glucose plus multiple daily injections.

Lastly, Kamble et al52 found unfavourable cost-effectiveness results for a sensor-augmented pump versus self-monitoring of blood glucose plus multiple daily injections.

We found no economic evaluations of continuous glucose monitoring in children with type 1 diabetes.

Conclusions

The economic evidence showed mixed results when comparing continuous glucose monitoring with self-monitoring of blood glucose. All studies indicated that continuous glucose monitoring was more effective but also more costly. No studies were conducted in children with type 1 diabetes. No study was conducted from the Ontario or Canadian health care perspective, and many had methodological limitations and uncertainties in the results.

PRIMARY ECONOMIC EVALUATION

The published economic evaluations identified in the economic evidence review addressed our interventions of interest, but none of them took a Canadian perspective. Owing to these limitations, we conducted a primary economic evaluation.

Research Question

What is the cost-effectiveness of continuous glucose monitoring compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose in adult patients with type 1 diabetes from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care?

Methods

The information presented in this report follows the reporting standards set out by the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards statement.73

Type of Analysis

We performed cost-utility and cost-effectiveness analyses. Our cost-effectiveness analysis assessed the cost per life-year saved. Our cost-utility analysis assessed the cost per QALY gained.

Target Population

The target population was adult patients, mean age of 27 years, mean A1C of 8.8%, diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and treated on average for 6 years (range 1 to 15 years).64,74

Our target population was based on the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial and the follow-up Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications study (n = 1,411), the only randomized controlled trial to follow patients with type 1 diabetes for more than 20 years and report diabetes-related complications.64,74 The mean age and mean A1C of our target population at baseline and for the disease duration were assumed from the control arm of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. The study population had an average baseline A1C that was higher than that reported in some studies of continuous glucose monitoring, but reflected that of the average diabetes population, which tends to keep blood glucose levels higher to avoid severe hypoglycemic events.

We were unable to develop an economic evaluation of continuous glucose monitoring in children, owing to a lack of data on utilities and probabilities for children with type 1 diabetes.

Perspective

We conducted this analysis from the perspective of the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Interventions

We conducted four economic evaluations of continuous glucose monitoring compared with self-monitoring of blood glucose. We took this approach (1) because the clinical review excluded studies that compared continuous glucose monitoring devices with each other and (2) so that we could consider continuous glucose monitoring devices as a class, without regard to manufacturer or type.

Our review of the economic literature assessed eight possible interventions used in clinical practice (see Economic Evidence Review, Types of Interventions). However, because of a lack of clinical evidence, our evaluation was limited to four interventions. Appendix 4 provides our reasons for including the four interventions and the associated references for the selected studies. Table 11 summarizes the interventions evaluated in the economic model.

Table 11:

Disease Interventions and Comparators Evaluated in the Primary Economic Model

| Intervention | Comparator |

|---|---|

| Standalone CGM device plus multiple daily injections | SMBG plus multiple daily injections |

| Sensor-augmented pump | SMBG plus multiple daily injections |

| Standalone CGM device plus insulin pump | SMBG plus insulin pump |

| Sensor-augmented pump | SMBG plus insulin pump |

Abbreviations: CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

We conducted a pairwise comparison (i.e., two at a time) of continuous glucose monitoring and self-monitoring of blood glucose. We considered continuous glucose monitoring devices approved in Canada and produced in 2010 or later. We did not rank the different continuous glucose monitoring devices by cost-effectiveness. For more details about the technologies we assessed, see the Background and Clinical Evidence Review sections.

Discounting and Time Horizon

We applied an annual discount rate of 1.5% to both costs and QALYs.75 We used a lifelong time horizon for all analyses.

Model Structure

We adapted a transition-state model structure developed by McQueen et al51 for patients with type 1 diabetes, and we used a Markov cohort model with a 1-year cycle to explore long-term disease progression. Our model included more health states than the McQueen et al model.51 We also included long-term diabetes complications and short-term acute complications (such as severe hypoglycemia).

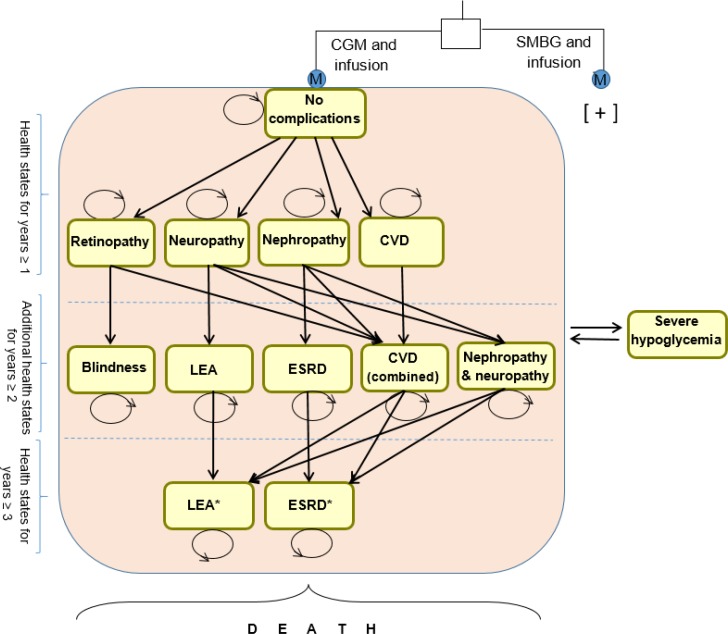

Our model consisted of 14 health states (Figure 4). All patients started in the “no complications” state. From the first year onward, they:

Figure 4: Continuous Glucose Monitoring Versus Self-Monitoring of Blood Glucose—Long-Term Markov Model of Complications in Patients With Type 1 Diabetesa.

Abbreviations: CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; CVD, cardiovascular disease, ESRD, end-stage renal disease; LEA, lower-extremity amputation; SMBG, self-monitoring of blood glucose.

aStraight arrows represent progression to a severe health state; curved arrows represent remaining in the same health state; straight arrows to and from severe hypoglycemia represent the probability of having a hypoglycemic event in any health state. All health states except no complications, retinopathy, neuropathy, and blindness had excess mortality. Infusion includes multiple daily injections or insulin pump. The model structure was adopted from McQueen et al.51

*Combined health states.

Stayed in the “no complications” state

-

Transitioned into one of the initial four diabetes complication health states:

∘ Retinopathy

∘ Neuropathy

∘ Nephropathy

∘ Cardiovascular disease

Died because of diabetes complications or other causes (i.e., entered the absorbing death state)

Patients in any health state could have a severe hypoglycemic event. We counted a number of severe hypoglycemic events for each health state. To account for the episodic nature of hypoglycemia, we estimated the probability of multiple hypoglycemic events for a 1-year cycle, based on the published literature.76

From the second year onward, patients could:

-

Move to a more severe condition state:

∘ Blindness

∘ Lower-extremity amputation

∘ End-stage renal disease

-

Move to a combined complication health state:

∘ Nephropathy and cardiovascular disease

∘ Neuropathy and cardiovascular disease

∘ Retinopathy and cardiovascular disease

∘ Neuropathy and nephropathy

Enter the death state

From the third year onward, patients with nephropathy and cardiovascular disease, neuropathy and cardiovascular disease, or neuropathy and nephropathy could die or transition to the most severe health states:

Lower-extremity amputation

End-stage renal disease

After the third year, patients were in the no complications state or had transitioned to any of the complication health states. Figure 4 provides a simplified schematic of the Markov model.

The Markov health states were based on a description of clinical outcomes from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial.76 The macrovascular (cardiovascular disease) and microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) complications of type 1 diabetes occur in later stages of the disease. Therefore, concomitant health states have attributes of both cardiovascular disease and retinopathy, nephropathy, or neuropathy.

No complications: Patients in this state are free from long-term major adverse events but can have short-term severe hypoglycemic events. They may experience microvascular or macrovascular complications over time, or die from any cause76

Retinopathy: Patients in this state have a growth of easily torn new blood vessels in the retina, as well as macular edema (swelling of part of the retina), which can lead to severe vision loss or blindness. This state includes patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy or worse, patients with clinically significant macular edema, and patients undergoing photocoagulation therapy76