Abstract

Basilar artery fenestration is an uncommon congenital dysplasia and may be associated with ischaemic stroke. We present a case of a previously healthy 36-year-old man who presented with vertigo and vomiting. MRI showed posterior circulation territory infarction. High-resolution magnetic resonance angiography revealed a slit-like fenestration in the basilar artery. This patient had no traditional vascular risk factors or aetiology of cryptogenic stroke. The patient recovered from his neurological deficit after antiplatelet therapy and was given prophylactic aspirin therapy. There was no recurrence of symptoms after 12 months of follow-up.

Keywords: neurology, stroke, neuroimaging

Background

Fenestration of a cerebral artery is a type of rare congenital vascular dysplasia. It is characterised by the division of an artery, with two distinct endothelium-lined channels within the lumen of a single artery.1 Among cerebral arteries, basilar artery fenestration is the most common form of fenestration.2 The incidence of basilar artery fenestration is reported to be around 2.3%.3 Cerebral artery fenestration has been reported in patients with cerebral ischaemia.4–9 We present the case of a 36-year-old man with cerebellar infarction. This patient was without any vascular risk factors. A basilar artery fenestration was detected by high-resolution MRI.

Case presentation

A 36-year-old man experienced a sudden onset of vertigo, vomiting, ataxia and unstable walking. He went to the emergency room of a regional hospital. Brain MRI showed acute cerebellar infarction (figure 1). Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed a fenestration in the basilar artery and a small right vertebral artery, but no other cerebrovascular disorders were discovered. The patient received aspirin (100 mg/day) and clopidogrel (75 mg/day). When he came to our hospital 1 month later, the symptoms had almost recovered, and there was no positive signs on neurological examination. He denied any trauma or medical history and had no smoking history. Examinations were performed, and no abnormal blood pressure, pathoglycaemia, dyslipidaemia, hyperhomocysteinaemia, coagulation disorders or immunological dysfunctions were noted. Holter ECG monitoring, Doppler echocardiography and transcranial Doppler ultrasound were performed, and no arrhythmia or cardiac or cerebrovascular pathological changes were found. Carotid colour ultrasound revealed no arterial stenosis or atherosclerosis. MRA re-examination indicated no cerebrovascular disorder except the basilar artery fenestration and a small right vertebral artery (figure 2). These changes were considered to be some kind of congenital variation. High-resolution MRI was performed and confirmed these changes (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Diffusion-weighted MRI revealed area of reduced diffusivity in the cerebellar vermis.

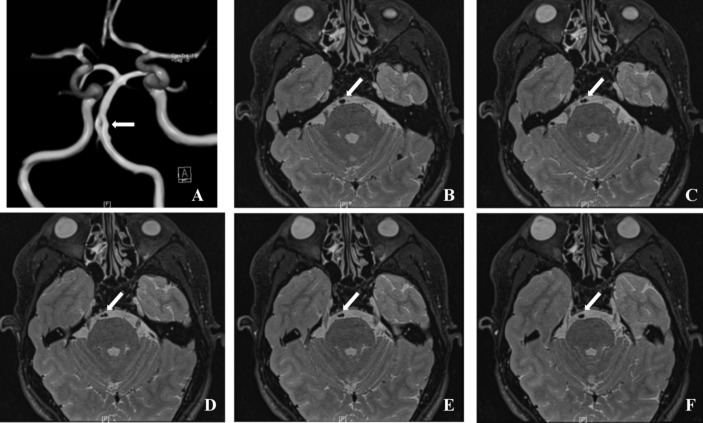

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance angiography revealed a small fenestration in the middle segment of the basilar artery (arrow).

Figure 3.

High-resolution MRI of the brain. (A) A small slit-like fenestration was seen in the middle segment of the basilar artery. (B–F) Axial plane images showing that the basilar artery was divided into two lumens, which converge after four slices (0.7 mm thickness).

Differential diagnosis

Basilar artery embolism.

Cerebral haemorrhage.

Treatment

Aspirin was administered at 100 mg/day for a long duration.

Outcome and follow-up

During the 12-months follow-up period, no recurrence of symptoms was observed.

Discussion

Fenestration of a cerebral artery is a rare congenital anomaly. According to the literature, cerebral artery fenestrations are mostly discovered in the basilar artery.2 We report the case of a young man with superior cerebellar infarction. MRA revealed that the culprit artery was the basilar artery. Some cases of cerebral artery fenestration in patients with cerebral ischaemia have been reported4–9; most of these cases are adults, except two cases in children.5 9 Almost all of the published adult cases had at least one vascular risk factor (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia and/or smoking). Gold and Crawford5 and Kloska et al9 described two paediatric cases of fenestration with infarction.7 Bernard et al reported an 18-year-old man with fenestrated vertebral arteries and recurrent stroke. All of these cases had no vascular risk factors or other diseases, suggesting the possibility that the fenestration itself could be a cause of cryptogenic stroke.

Jeong et al4 reported five cases of cerebrovascular fenestration. They indicated that fenestration caused a local change in haemodynamics and blood flow, leading to cerebral ischaemia. Nevertheless, the fenestrations reported by Jeong et al4 were in the middle cerebral artery, while the fenestration in our patient was in the basilar artery. The mechanism that could link fenestration and stroke is speculative at best, and computerised haemodynamics modelling studies will be needed to address this issue. Nevertheless, based on the available literature,4 7 9 10 it could be hypothesised that the local haemodynamics of the fenestration causes turbulences in blood flow, which could stress and damage the vascular endothelium, leading to decreased blood flow or atherosclerosis. Indeed, some cases of thrombosis associated with fenestration of various arteries have been reported.7 9 10 However, Pleş et al8 reported a case in which brain ischaemia was caused by reduced blood flow due to the fenestration. In addition, Gold and Crawford5 reported a case of basilar artery fenestration in which no thrombus or aneurysm could be found. Therefore, additional studies are necessary to determine the exact association and mechanisms of stroke with brain artery fenestration. In addition, fenestration has been associated with aneurysm, indicating that fenestration could also be associated with haemorrhagic stroke,11 12 and a case of internal carotid artery fenestration has been reported to be associated with both aneurysm and ischaemic stroke.6

Nevertheless, it is essential to emphasise that there is currently no evidence showing that basilar artery fenestration could cause stroke and that it is a working hypothesis in the absence of other identifiable cause of stroke. Despite the evidence presented above suggesting that patients with fenestration may be at increased risk of stroke, the evidence is not strong enough to support any active prophylaxis in these patients, except perhaps to play on modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, tobacco and alcohol. In addition, the treatment of patients with cerebral infarction and fenestration is unclear. In the cases reported here, a conventional treatment approach was used and included antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulant therapy. Vascular interventional therapy should be explored. No recurrence of symptoms were observed during the 12-month follow-up.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, our patient is the first reported patient with cerebellar infarction associated with basilar artery fenestration and in whom no traditional vascular risk factors or reported aetiology of cryptogenic stroke could be found. Compared with conventional MRI, high-resolution MRI could be more helpful for observing the fenestrated vascular structures.

Learning points.

Fenestration of cerebral arteries is an uncommon congenital dysplasia.

Fenestration may be associated with ischaemia because of possible local changes in haemodynamics, but validation is needed.

Antiplatelet therapy can be useful to patients with cerebellar infarction and fenestration when they do not have any other vascular risk factors.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: XW. Acquisition of data: JZ. Drafting the article: XW and JZ. Final approval of the version published: AL and BC.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Black SP, Ansbacher LE. Saccular aneurysm associated with segmental duplication of the basilar artery. A morphological study. J Neurosurg 1984;61:1005–8. 10.3171/jns.1984.61.6.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanders WP, Sorek PA, Mehta BA. Fenestration of intracranial arteries with special attention to associated aneurysms and other anomalies. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1993;14:675–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao LY, Guo X, Zhou JJ, et al. Basilar artery fenestration detected with CT angiography. Eur Radiol 2013;23:2861–7. 10.1007/s00330-013-2890-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong SK, Kwak HS, Cho YI. Middle cerebral artery fenestration in patients with cerebral ischemia. J Neurol Sci 2008;275:181–4. 10.1016/j.jns.2008.07.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gold JJ, Crawford JR. An unusual cause of pediatric stroke secondary to congenital basilar artery fenestration. Case Rep Crit Care 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/627972 [Epub ahead of print 17 Jan 2013]. 10.1155/2013/627972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YY, Chang FC, Hu HH, et al. Fenestration of the supraclinoid internal carotid artery associated with aneurysm and ischemic stroke. Surg Neurol 2007;68:S60–S63. 10.1016/j.surneu.2007.05.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bernard TJ, Mull BR, Handler MH, et al. An 18-year-old man with fenestrated vertebral arteries, recurrent stroke and successful angiographic coiling. J Neurol Sci 2007;260:279–82. 10.1016/j.jns.2007.04.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pleş H, Kimball D, Miclăuş GD, et al. Fenestration of the middle cerebral artery in a patient who presented with transient ischemic attack. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2015;56:861–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kloska SP, Schlegel PM, Sträter R, et al. Causality of pediatric brainstem infarction and basilar artery fenestration? Pediatr Neurol 2006;35:436–8. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berry AD, Kepes JJ, Wetzel MD. Segmental duplication of the basilar artery with thrombosis. Stroke 1988;19:256–60. 10.1161/01.STR.19.2.256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel MA, Caplan JM, Yang W, et al. Arterial fenestrations and their association with cerebral aneurysms. J Clin Neurosci 2014;21:2184–8. 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanaka S, Tokimura H, Makiuchi T, et al. Clinical presentation and treatment of aneurysms associated with basilar artery fenestration. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:394–401. 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]