Abstract

Isolated facial nerve palsy is a common presentation of Bell’s palsy, but rarely seen in pontine lesions. The patient being reported is a middle-aged man who developed isolated facial nerve palsy and was initially treated as Bell’s palsy. However, on MRI of the brain, he was found to have pontine haemorrhage. He was managed conservatively and improved. Pontine haemorrhage as an aetiology for isolated facial nerve palsy is a rare scenario, which often goes misdiagnosed and treated as Bell’s palsy.

Keywords: pontine haemorrhage, Bell’s palsy, facial nerve, facial palsy, hypertension

Background

Bell’s palsy is characterised by acute-onset unilateral facial paralysis of unknown aetiology. The symptoms resolve over a period of 6 months.1 2 Facial paralysis following pontine stroke is uncommon. Though facial paralysis due to pontine infarct has been reported,3 pontine haemorrhage causing the same is extremely rare. This case, therefore, is aimed at emphasising the consideration of pontine lesions as a cause for isolated facial palsy, before attributing it to Bell’s palsy.

Case presentation

A 46-year-old man, with no known comorbidities, presented with sudden-onset facial deviation to the right, which he noticed while waking from sleep in the morning. He also developed a slurred speech and difficulty in closing his left eye. There was no associated headache, deafness, tinnitus, ataxia or dysarthria. He did not have any fever, earache, rashes, limb weakness or sensory symptoms. There were no other systemic complaints. For this, he consulted a nearby doctor and was told to have Bell’s palsy (blood pressure was 140/90 mm Hg). Brain imaging was not done. He was given oral acyclovir and prednisolone. There was no progression or regression in symptoms over the next 1 week, so he decided to take an opinion at our hospital.

On presentation, he was conscious, oriented and afebrile, with a regular pulse rate of 80/min and blood pressure of 170/100 mm Hg. There was no mastoid tenderness, rashes or hearing impairment. His neurological examination revealed deviation of his angle of mouth to the right side (figure 1), loss of forehead creases and nasolabial fold on the left, inability to close his left eye and Bell’s phenomenon of left eye. Other systemic examinations were normal. Carotid bruit was absent.

Figure 1.

Deviation of angle of mouth to the right side.

Investigations

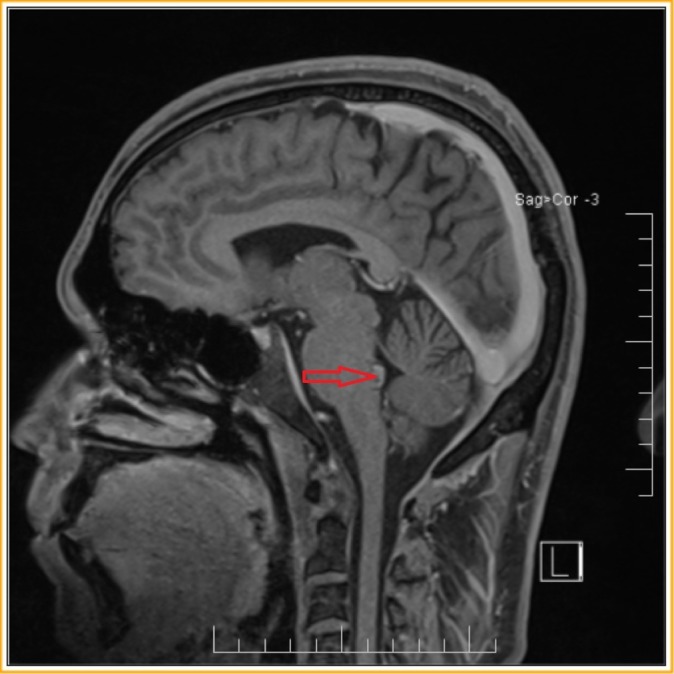

His MRI of brain was suggestive of pontine haemorrhage (figure 2). Digital subtraction angiography did not show any arteriovenous malformation or aneurysm. His blood investigations (complete blood count, renal and liver functions, thyroid profile, electrolytes, prothrombin time/international normalised ratio, glycated haemoglobin, HIV), chest X-ray, ECG and echocardiogram were normal.

Figure 2.

MRI of the brain (T1 weighted) showing hyperintensity at the floor of the fourth ventricle in the region of facial nucleus.

Treatment

He was started on perindopril (4 mg once daily), atorvastatin (40 mg at night) and mannitol, along with physiotherapy.

Outcome and follow-up

His modified Rankin Scale and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale on presentation was 1 and did not show any progression. He was discharged on day 14 of admission, with an improvement in House-Brackmann score, that is, from grade V to III.

Discussion

The incidence of cerebrovascular accidents has shown a rapid increase in the low/middle-income countries. Majority of the cases are due to ischaemic strokes, followed by intracranial haemorrhage which accounts for 10%–20% of all stroke cases.4 Hypertensive atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease and cerebral amyloid angiopathy account for about 80% of intracranial haemorrhage cases.5 Non-traumatic intracranial haemorrhages are due to age-related vessel wall degenerative changes, diabetes and hypertension, resulting in the formation of Charcot-Bouchard microaneurysms and lipohyalinosis of small arterioles.6

The facial nerve has two components: the motor and sensory roots. The motor fibres are responsible for muscles of facial expression. About 72% of facial palsies are due to Bell’s palsy, and are usually seen following an immunisation or viral infection. Other aetiologies include Mobius syndrome, motor neuron disease, pontine lesions, cerebellopontine angle mass lesions, diabetes mellitus, HIV infection and Lyme disease.2 7

Pontine haemorrhage accounts for 5%–9% of intracranial haemorrhage; and the incidence is highest between 40 and 50 years of age. They are caused by hypertension, anticoagulant therapy, inflammatory vascular disease or vascular malformations like arteriovenous haemangiomas, cavernous haemangiomas and capillary telangiectasias.8 9 Acute-onset coma, constricted pupils, quadriplegia, early-onset respiratory arrest and sudden death are the main manifestations.10 Because of the close proximity of pons to the cranial nerve nuclei and due to the presence of vascular anomalies, these patients present with a variety of atypical manifestations. There are reports of one-and-a-half syndrome, eight-and-a-half syndrome, fifteen-and-a-half syndrome, sixteen syndrome and twenty four syndrome in association with pontine strokes.11–15 Vascular pontine lesions account for only 1% of facial palsy cases.16 Even more unlikely is the presentation of isolated facial nerve palsy, which can be a diagnostic challenge. Ipsilateral lower motor neuron facial palsy is seen when the facial nerve on the same side of the lesion gets damaged at the fascicular level. Meanwhile, an upper motor neuron facial palsy can be seen on the opposite side if the upper motor neuron fibres to the opposite seventh nerve are damaged as they decussate.17 Hypertension may or may not be a manifestation of pontine haemorrhage.18

Patients with Bell’s palsy present with acute-onset unilateral paresis of the facial muscles along with numbness of the affected side without any sensory deficit. Loss of lacrimation, taste disorders, pain behind the ear and ipsilateral hyperacusis are some of the other features.16 19 20 The recommendations for clinical practice guidelines in cases of Bell’s palsy are (1) assessment of history and physical examination in order to exclude other identifiable causes of facial paresis or paralysis in case of acute-onset unilateral facial paresis or paralysis; (2) prescribing oral steroids within 72 hours of symptom onset in patients 16 years and older; (3) avoiding oral antiviral therapy alone for patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy and (4) the use of eye protection in patients with impaired eye closure. Other recommendations include (1) avoiding routine laboratory testing in patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy; (2) avoiding routinely diagnostic imaging; (3) avoiding electrodiagnostic testing in patients with incomplete facial paralysis and (4) reassessment or reference to a facial nerve specialist in case of new or worsening neurological findings, development of ocular symptoms or incomplete facial recovery 3 months after the onset of initial symptom.21

Facial paresis has been reported in 3%–17% cases of severe hypertension, mainly in children. Small haemorrhages into the facial canal and neural partial necrosis are the probable mechanisms. In elderly age groups, it may be associated with increased vascular pathology.22–25

Pontine haemorrhage presenting as isolated facial nerve palsy is a rare scenario, with less than a handful of cases being reported in medical literature. Owing to its rarity, the condition may go unrecognised and get treated as Bell’s palsy. Moreover, patients with pontine haemorrhage may present with normal blood pressure, making it difficult to differentiate with Bell’s palsy. Hypertension itself may cause facial nerve palsy. The awareness of association of pontine lesions and hypertension with facial nerve paresis is important to avoid the misdiagnosis of Bell’s palsy, as the condition can be worsened by steroid therapy. Hence, imaging modalities should be used to confirm the aetiology of facial palsy, especially in the setting of hypertension.

Learning points.

Pontine lesions are a rare cause for isolated facial nerve palsy.

Pontine haemorrhages may or may not present with elevated blood pressure.

Severe hypertension can cause facial paresis.

Consideration of pontine lesions as a cause for isolated facial palsy, before attributing it to Bell’s palsy, especially in the setting of elevated blood pressure.

Importance of imaging modalities in confirming aetiology of facial palsy.

Footnotes

Contributors: UK: Critical revision of manuscript and treating neurologist. RGM: Concept and design of case report, reviewed the literature, manuscript preparation and treating physician. CJ: Critical revision of manuscript and treating neurologist. RNS: Resident in-charge.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Bell’s palsy: prognosis and treatment. http://www.uptodate.com/contents/bells-palsy-prognosis-and-treatment?

- 2.Holland NJ. Weiner GM: Recent developments in Bell’s palsy. BMJ 2004;329:553–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karadan U, Manappallil RG. Pontine infarct masquerading as Bell’s Palsy. Journal of Case Reports 2017;7:352–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. . Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:355–69. 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutherland GR, Auer RN. Primary intracerebral hemorrhage. J Clin Neuroscience 2006;13:511–7. 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher CM. Pathological observations in hypertensive cerebral hemorrhage. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1971;30:536–50. 10.1097/00005072-197107000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell WW. Pocket guide & toolkit to DeJong’s Neurologic Examination. 1st ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008:119–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bewermeyer H, Neveling M, Ebhardt G, et al. . [Spontaneous pontine hemorrhage]. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 1984;52:259–76. 10.1055/s-2007-1002024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bewermeyer H, Hojer C, Szelies B, et al. . [Spontaneous pontine hemorrhage. An analysis of 38 cases]. Nervenarzt 1988;59:640–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silverstein AJ. Primary pontine haemorrhage : Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Handbook of Clinical Neurology, Vascular diseases of Nervous System. Amsterdam: North Holland Inc, 1972:37–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher CM. Some neuro-ophthalmological observations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1967;30:383–92. 10.1136/jnnp.30.5.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nandhagopal R, Krishnamoorthy SG. Eight-and-a-half syndrome Journal of Neurology. Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2006;77:463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bae JS, Song HK. One-and-a-half syndrome with facial diplegia: the 15 1/2 syndrome? J Neuroophthalmol 2005;25:52–3. 10.1097/00041327-200503000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Connors R, Ngan V, Howard J. A case of complete lateral gaze paralysis and facial diplegia: the 16 syndrome. J Neuroophthalmol 2013;33:69–70. 10.1097/WNO.0b013e3182737855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karadan U, Supreeth RN, Manappallil RG, et al. . Twenty-Four Syndrome: An Untold Presentation of Pontine Hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2018. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2017.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002;549:4–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patten J. Neurological differential diagnosis. 2nd ed: Springer, 2000:172–3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goto N, Kaneko M, Hosaka Y, et al. . Primary pontine hemorrhage: clinicopathological correlations. Stroke 1980;11:84–90. 10.1161/01.STR.11.1.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perry JR, Hasso AN. Magnetic resonance imaging of cranial nerve VII. Top Magn Reson Imaging 1996;8:155–63. 10.1097/00002142-199606000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roob G, Fazekas F, Hartung HP. Peripheral facial palsy: etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Eur Neurol 1999;41:3–9. 10.1159/000007990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. . Clinical practice guideline: Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013;149(3 Suppl):S1–27. 10.1177/0194599813505967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aynaci FM, Sen Y. Peripheral facial paralysis as initial manifestation of hypertension in a child. Turk J Pediatr 2002;44:73–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bademosi O, Ogunlesi TO, Osuntokun BO. Clinical study of unilateral peripheral facial nerve paralysis in Nigerians. Afr J Med Med Sci 1987;16:197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar S, Jain S, Diwan SK, et al. . Severe systemic hypertension presenting with infranuclear facial palsy. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis 2011;1:83–4. 10.4103/2231-0738.77540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ellis SL, Carter BL, Leehey MA, et al. . Bell’s palsy in an older patient with uncontrolled hypertension due to medication nonadherence. Ann Pharmacother 1999;33:1269–73. 10.1345/aph.19129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]