Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the clinical effectiveness of switching to insulin degludec (IDeg) in insulin‐treated patients with either type 1 diabetes (T1DM) or type 2 diabetes (T2DM) under conditions of routine clinical care.

Materials and Methods

This was a multicentre, retrospective, chart review study. In all patients, basal insulin was switched to IDeg at least 6 months before the start of data collection. Baseline was defined as the most recent recording during the 3‐month period before first prescription of IDeg. Values are presented as mean [95%CI].

Results

T1DM (n = 1717): HbA1c decreased by −2.2 [−2.6; −2.0] mmol/mol (−0.20 [−0.24; −0.17]%) at 6 months vs baseline (P < .001). Rate ratio of overall (0.79 [0.69; 0.89]), non‐severe nocturnal (0.54 [0.42; 0.69]) and severe (0.15 [0.09; 0.24]) hypoglycaemia was significantly lower in the 6‐month post‐switch period vs the pre‐switch period (P < .001 for all). Total daily insulin dose decreased by −4.88 [−5.52; −4.24] U (−11%) at 6 months vs baseline (P < .001). T2DM (n = 833): HbA1c decreased by −5.6 [−6.3; −4.7] mmol/mol (−0.51 [−0.58; −0.43] %) at 6 months vs baseline (P < .001). Rate ratio of overall (0.39 [0.27; 0.58], P < .001), non‐severe nocturnal (0.10 [0.06; 0.16], P < .001) and severe (0.075 [0.01; 0.43], P = .004) hypoglycaemia was significantly lower in the 6‐month post‐switch period vs the pre‐switch period. Total daily insulin dose decreased by −2.48 [−4.24; −0.71] U (−3%) at 6 months vs baseline (P = .006). Clinical outcomes for T1DM and T2DM at 12 months were consistent with results at 6 months.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that switching patients to IDeg from other basal insulins improves glycaemic control and significantly reduces the risk of hypoglycaemia in routine clinical practice.

Keywords: basal insulin, hypoglycaemia, insulin analogues, observational study

1. INTRODUCTION

Insulin degludec (IDeg) is a basal insulin with a unique mode of protraction that provides an ultra‐long duration of action, exceeding 42 hours, and low day‐to‐day variability in blood glucose‐lowering effect compared with insulin glargine U100 and U300.1, 2, 3 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in adults, using a treat‐to‐target approach, have demonstrated that IDeg is associated with a reduced risk of hypoglycaemia, vs other insulin analogues, at equivalent levels of glycaemic control.4, 5, 6, 7, 8

RCTs are the gold‐standard for comparing the safety and efficacy of new therapies with existing treatment options; however, because of restrictive inclusion and exclusion criteria, the use of treat‐to‐target titration algorithms and the close management of patients during investigations, RCTs have a high degree of internal validity but lower generalizability. Therefore, it can be challenging to extrapolate the results to an unselected population.9 Real‐world studies are a valuable additional source of evidence that complement clinical trial data by assessing the external validity of new therapies, thus bridging the knowledge gap between RCTs and clinical practice.

Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of IDeg in a real‐world population may help to inform the prescribing decisions of clinicians. Single‐centre non‐interventional studies have reported reductions in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and the risk of hypoglycaemia for patients switching to IDeg from other basal insulins,10, 11 but there are currently no large multicentre studies evaluating the performance of IDeg in a real‐world population.

The aim of the EUropean TREsiba AudiT (EU‐TREAT) study was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of switching to IDeg in a broad population of insulin‐treated adult patients with either type 1 diabetes (T1DM) or type 2 diabetes (T2DM) in conditions that reflect routine clinical care in multiple centres across Europe.

2. STUDY POPULATION AND METHODS

This was a European, multicentre, retrospective, non‐interventional chart review study, using medical records of patients with T1DM or T2DM, who switched from any basal insulin to IDeg with a minimum of 6 months' follow‐up after switching. All patients who received at least 1 prescription of IDeg were considered for study participation, including those who had discontinued IDeg at the time of inclusion in this study. Data were collected between December 5, 2015 and April 17, 2016 at outpatient clinics in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy and Switzerland.

A contract research organization (ICON plc, Dublin, Ireland) was responsible for investigational site selection and training, independent of the study sponsor. Potential investigators were randomly drawn in a sequential manner from databases of IDeg prescribers and contacted for participation. Confirmed investigators invited eligible patients in a consecutive manner to participate and sign the study informed consent form, starting with the patient who attended the clinic most recently and then working backwards. Competitive recruitment was used until the sample size was reached.

Two periods of medical history were reported: before (pre‐switch) and after (post‐switch) the initiation date of IDeg. Baseline was defined as the closest date before switching to IDeg (up to 3 months before IDeg initiation). Outcome data, both pre‐ and post‐switch, were collected in a ± 3‐month window around the defined evaluation time points: 6 months pre‐ and post‐switch, and at the time of switch, as well as 12 months pre‐ and post‐switch, whenever available. Inclusion criteria were age≥18 years at the time of starting IDeg and a current diagnosis of either T1DM or T2DM. Patients were required to have switched to IDeg (± oral antidiabetic drugs [OADs] ± prandial insulin) from any other basal insulin (± OADs ± prandial insulin) at least 6 months before data collection, and to have been treated with basal insulin for at least 6 months before switching. Patients had at least 1 documented medical visit in the first 9 months after IDeg initiation. Minimum available data at the time of IDeg initiation were age, type of diabetes, HbA1c, known duration of diabetes, duration and type of insulin treatment, medical follow‐up at the study site for at least 1 year, and an estimated glomerular filtration rate value in the last 12 months. Patients were excluded if they had previously participated in this or any other non‐interventional study on IDeg, or any other diabetes clinical trial, or if they were in receipt of any investigational medicinal product up to 12 months before or any time after the initiation of IDeg. Patients treated by continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion or premix insulin in the 6 months before receiving IDeg were excluded.

The primary objective was to assess the clinical effectiveness of IDeg, used in conjunction with any other antidiabetic treatment, by analysing whether treatment was associated with a change in HbA1c after 6 months, compared with the last value on previous basal insulin before switch. A secondary objective was to assess whether IDeg, used in combination with any other antidiabetic treatment, was associated with a change in HbA1c at 12 months or any change in fasting plasma glucose (FPG), the proportion of patients experiencing hypoglycaemia, rates of hypoglycaemia, insulin dose and body weight. Another secondary objective was to understand the use of IDeg in real life (ie, reasons for switching to and discontinuation of IDeg). Hypoglycaemic events were those recorded by the physician/nurse in the patient charts. Nocturnal hypoglycaemia was defined as any event in which the words “nocturnal” or “night” (or their equivalent in the local language) were present in the patient records. Severe hypoglycaemia was defined as an episode requiring the assistance of another person to actively administer carbohydrate, glucagon or other corrective actions. For each patient, comparisons of hypoglycaemic episodes were based on similar time frames before and after switch (ie, −6 to 0 months vs 0 to +6 months and likewise for the 12‐month period before/after comparisons, when appropriate).

Informed consent was obtained from patients, in accordance with the requirements of the Declaration of Helsinki, before any study‐related activities were undertaken. A list of independent ethics committees for participating centres is provided online in Table S1. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02662114.

2.1. Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics and demographics were reported using descriptive statistics, with mean (standard deviation [SD]) or percentage as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared using a paired t test. Comparisons for continuous endpoints were estimated as a baseline‐adjusted change using analysis of covariance. Covariates included country, age, body mass index (BMI), gender, FPG, diabetes duration, duration of insulin therapy and type of basal injections. Count and rate data were analysed using negative binomial estimators for patients with data at both pre‐ and post‐switch timepoints. Categorical variables were analysed using an appropriate method for the level of measurement associated with paired data (ie, McNemar's test for univariable paired comparisons; Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test for stratified paired comparisons). Conditional logistic regression modelling was used to assess the likelihood of having ≥1 hypoglycaemic event. All statistical tests were two‐sided. The threshold for significance was P < .05. P values are reported without correction for multiplicity, and should be interpreted as descriptive for the secondary objectives.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study population demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 2550 patients were included in the study (T1DM = 1717, T2DM = 833). Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were 96 sites across 6 countries (Austria, 12; Denmark, 7; Germany, 45; Greece, 13; Italy, 13 and Switzerland, 6). The majority of patients were from Germany (49.9% of patients with T1DM, 68.2% with T2DM).

Table 1.

Population demographics and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | T1DM | T2DM |

|---|---|---|

| Full analysis set (FAS), n | 1717 | 833 |

| Median age, years (IQR) | 49.0 (36.0, 59.0) | 65.0 (58.0, 72.0) |

| Female/Male, % | 45.7/54.3 | 42.4/57.6 |

| Country, n (%) | ||

| Austria | 148 (8.6) | 23 (2.8) |

| Denmark | 83 (4.8) | 1 (0.1) |

| Italy | 397 (23.1) | 153 (18.4) |

| Switzerland | 63 (3.7) | 56 (6.7) |

| Greece | 169 (9.8) | 32 (3.8) |

| Germany | 857 (49.9) | 568 (68.2) |

| History of diabetes | ||

| Median duration of diabetes, years (IQR) | 19.2 (10.9, 29.8) | 15.9 (11.6, 21.9) |

| Median duration of insulin treatment, years (IQR) | 18.6 (10.3, 29.3) | 8.2 (4.7, 13.8) |

| Median BMI, kg/m2 (IQR) | 25.6 (23.1, 28.7) | 33.0 (29.1, 37.6) |

| Weight, kg (SD) | 77.4 (16.4) | 97.2 (21.0) |

| HbA1c, % (SD) | 8.0 (1.3) | 8.4 (1.4) |

| HbA1c, mmol/mola (SD) | 64 (14) | 68 (15) |

| FPG, mmol/La (SD)[mg/dL] (SD) | 9.1 (3.8)[163.4] (68.6) | 9.9 (3.0)[178.9] (54.4) |

| Insulin regimen before switch, n (%) | ||

| Basal insulin only | 1 (0.1) | 187 (22.4) |

| Basal–bolus | 1693 (98.6) | 621 (74.5) |

| Basal insulin before switch, n (%) | ||

| NPH insulin | 53 (3.1) | 95 (11.4) |

| Insulin glargine U100 | 888 (51.7) | 259 (31.1) |

| Insulin detemir | 726 (42.3) | 415 (49.8) |

| Other | 27 (1.6) | 39 (4.7) |

| Missing | 23 (1.3) | 25 (3.0) |

| Bolus insulin before switch, n (%) | ||

| Insulin glulisine | 146 (8.5) | 70 (8.4) |

| Insulin lispro | 504 (29.4) | 206 (24.7) |

| Insulin aspart | 883 (51.4) | 290 (34.8) |

| Other | 94 (5.5) | 66 (7.9) |

| Missing | 90 (5.2) | 201 (24.1) |

| Daily dose of basal insulin at baseline, U (SD) | ||

| Basal insulin only | N/A | 32.0 (18.9) |

| Basal–bolus | 25.7 (13.9) | 38.5 (26.5) |

| Daily dose of prandial insulin at baseline, U (SD) | 26.5 (15.2) | 54.1 (35.3) |

| Frequency of basal insulin injections, n (%) | ||

| Once daily | 857 (49.9) | 520 (62.4) |

| Twice or more daily | 786 (45.8) | 234 (28.1) |

| Unknown/missing | 74 (4.3) | 79 (9.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; IQR, interquartile range; N/A, not applicable; NPH, neutral protamine Hagedorn; SD, standard deviation; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; T2DM, type 2 diabetes; U, units; U100, 100 units/mL.

Values are mean (SD), unless otherwise stated.

Calculated, not measured.

Patients with T1DM were (mean (SD)) aged 47.7 (15.6) years, with a duration of diabetes of 21.8 (13.5) years and duration of insulin treatment of 21.2 (13.5) years. Patients weighed 77.4 (16.4) kg, had a BMI of 26.3 (4.8) kg/m2, with HbA1c of 64 (14) mmol/mol (8.0 (1.3)%). Nearly all patients were on basal–bolus regimens. Before switching to IDeg, 51.7% and 42.3% of patients were receiving insulin glargine U100 and insulin detemir, respectively (Table 1). Half of the patients used once‐daily basal insulin injection (Table 1).

T2DM patients were aged 64.6 (10.5) years, with a duration of diabetes of 17.5 (8.1) years, and duration of insulin treatment was 9.7 (6.3) years. Patients weighed 97.2 (21.0) kg, had a BMI of 33.6 (6.3) kg/m2, with HbA1c of 68 (15) mmol/mol (8.4 (1.4)%). Basal insulin‐only regimens were prescribed for 22.4% of patients, with 74.5% on basal–bolus regimens. Before switching to IDeg, 49.8% and 31.1% of patients were receiving insulin detemir and insulin glargine U100, respectively. The proportion of patients injecting basal insulin once daily was 62.4% (Table 1). There was no change in the number of OADs prescribed for each patient between the pre‐ and post‐switch periods (data not shown). OAD use in patients with T2DM at baseline is presented in Table S2.

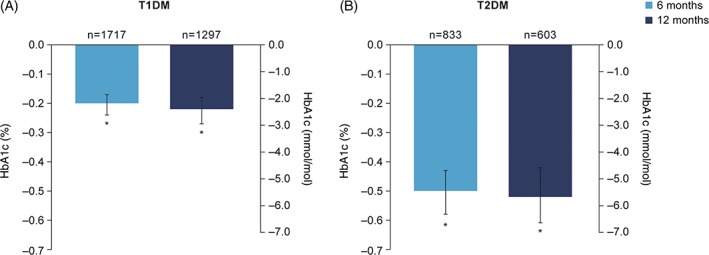

3.2. Glycaemic control

In T1DM, mean [95% CI] HbA1c decreased significantly by −2.2 [−2.6; −1.9] mmol/mol (−0.20 [−0.24; −0.17]%) at 6 months, compared with baseline, and this was maintained at 12 months (−2.4 [−3.0; −2.0] mmol/mol (−0.22 [−0.27; −0.18]%); P < .001 for both) (Figure 1A). In T2DM, mean HbA1c decreased significantly by −5.6 [−6.3; −4.7] mmol/mol (−0.51 [−0.58; −0.43]%) at 6 months, compared with baseline, and this was maintained at 12 months (−5.7 [−6.7; −4.6] mmol/mol (−0.52 [−0.61; −0.42]%); P < 001 for both) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Change from baseline HbA1c in patients with A, T1DM and B, T2DM. *P < .001 vs baseline. Data are LSMeans. Multivariate ANCOVA model controlled for: country, age, BMI, gender, diabetes duration, duration of insulin therapy and type of basal injections. Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; LSMeans, least‐squares means; n, number of patients with data; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; T2DM, type 2 diabetes

In T1DM, mean FPG decreased significantly by −1.03 [−1.32; −0.76] mmol/L (−18.72 [−23.81; −13.63] mg/dL) at 6 months, compared with baseline, P = .001. At 12 months, FPG was −1.17 [−1.52; −0.82] mmol/L (−21.02 [−27.35; −14.69] mg/dL) lower vs baseline, P < .001 (data not shown). In T2DM, mean FPG decreased significantly by −1.31 [−1.69; −0.94] mmol/L (−23.65 [−30.41; −16.90] mg/dL) at 6 months, compared with baseline, P < .001. At 12 months, FPG was −1.47 [−2.00; −0.93] mmol/L (−26.42 [−36.00; −16.83] mg/dL) lower vs baseline, P = .001 (data not shown). The pre‐switch type of basal insulin did not have a significant effect on change in HbA1c or FPG at follow‐up in either T1DM or T2DM patients (data not shown).

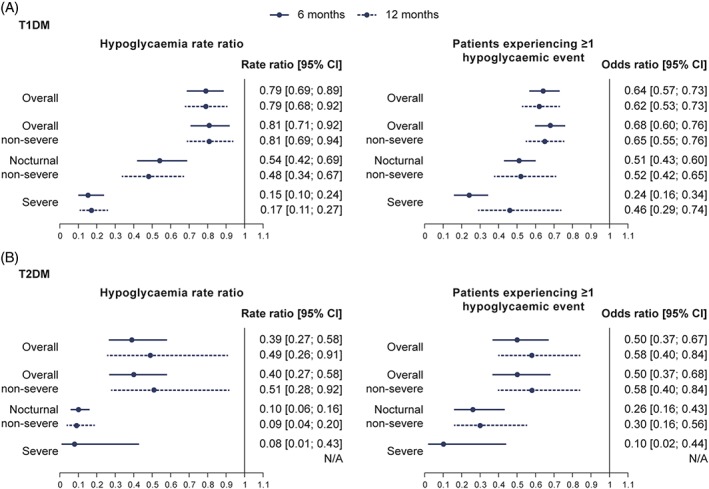

3.3. Hypoglycaemia

In T1DM, switching to IDeg resulted in significantly lower rates of overall hypoglycaemia (21% reduction), overall non‐severe hypoglycaemia (19% reduction), nocturnal non‐severe hypoglycaemia (46% reduction) and severe hypoglycaemia (85% reduction) post‐switch vs pre‐switch, in the 6‐month period comparison (Table S3; Figure 2A). The results from the 12‐month post‐switch vs pre‐switch comparisons were similar (Table S4; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Hypoglycaemia rate ratios and odds ratios for A, T1DM and B, T2DM patients experiencing more than 1 hypoglycaemic event post‐ vs pre‐switch. Hypoglycaemia rate ratio was estimated using negative binomial regression model controlled for: age, BMI, gender, diabetes duration and duration of insulin therapy. Modelled results are based only on patients with complete data in both the pre‐ and post‐switch period. Conditional logistic regression modelling was used to assess the likelihood of having ≥1 hypoglycaemic event. N/A, rate ratio could not be calculated because there were too few events in the post‐switch period. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; T2DM, type 2 diabetes

In T2DM, switching to IDeg resulted in significantly lower rates of overall hypoglycaemia (61% reduction), overall non‐severe hypoglycaemia (60% reduction), nocturnal non‐severe hypoglycaemia (90% reduction) and severe hypoglycaemia (92% reduction) post‐switch vs pre‐switch, in the 6‐month period comparison (Table S5; Figure 2B). Similar results were observed at 12 months, where comparisons were possible (Table S6; Figure 2B). The proportion of patients experiencing ≥1 overall, nocturnal non‐severe or severe hypoglycaemic event decreased significantly in the post‐switch period in both T1DM and T2DM (Table S7; Figure 2). The pre‐switch type of basal insulin did not have a significant effect on the rate of hypoglycaemia at follow‐up in either T1DM or T2DM (data not shown).

3.4. Insulin dose

In T1DM, at 6 months, daily basal insulin dose, daily prandial insulin dose and total daily insulin dose decreased by −3.15 U (−12%), −1.86 U (−7%) and −4.88 U (−11%), respectively, compared with baseline (P < .001 for all) (Table 2). At 12 months, daily basal insulin dose, daily prandial insulin dose and total daily insulin dose decreased by −3.32 U (−13%), −2.12 U (−8%) and −5.28 U (−11%), respectively, compared with baseline (P < .001 for all) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Change in mean daily insulin doses at 6 and 12 months

| 6 months | 12 months | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline, U (SD) | Change from baseline, U [95% CI] | Change from baseline, % | P | n | Baseline, U (SD) | Change from baseline, U [95% CI] | Change from baseline, % | P | |

| T1DM | ||||||||||

| Daily dose of basal insulin | 1556 | 25.71 (7.29) | −3.15 [−3.49; −2.80] | −12.25 | P < .001 | 1131 | 26.05 (7.76) | −3.32 [−3.74; −2.89] | −12.74 | P < .001 |

| Basal dose adjusted for body weight (U/kg) | 1229 | 0.33 (0.15) | −0.04 [−0.05; −0.04] | −13.33 | P < .001 | 891 | 0.34 (0.17) | −0.05 [−0.05; −0.04] | −14.12 | P < .001 |

| Daily dose of prandial insulin | 1146 | 26.46 (7.46) | −1.86 [−2.28; −1.44] | −7.03 | P < .001 | 815 | 26.75 (7.67) | −2.12 [−2.65; −1.60] | −7.93 | P < .001 |

| Prandial dose adjusted for body weight (U/kg) | 885 | 0.35 (0.17) | −0.03 [−0.04; −0.02] | −8.57 | P < .001 | 625 | 0.36 (0.18) | −0.03 [−0.04; −0.03] | −9.44 | P < .001 |

| Total daily dose of insulin | 1511 | 46.29 (13.10) | −4.88 [−5.52; −4.24] | −10.54 | P < .001 | 1097 | 46.42 (12.66) | −5.28 [−6.00; −4.56] | −11.37 | P < .001 |

| Total daily dose adjusted for body weight (U/kg) | 1194 | 0.60 (0.28) | −0.07 [−0.08; −0.06] | −12.00 | P < .001 | 862 | 0.61 (0.28) | −0.08 [−0.09; −0.07] | −12.62 | P < .001 |

| T2DM | ||||||||||

| Daily dose of basal insulin | 720 | 37.04 (14.54) | −0.88 [−1.86; 0.10] | −2.38 | .0772 | 479 | 38.16 (18.20) | −1.54 [−2.98; −0.11] | −4.04 | .0353 |

| Basal dose adjusted for body weight (U/kg) | 564 | 0.38 (0.25) | −0.01 [−0.02; −0.00] | −3.16 | .0259 | 370 | 0.40 (0.28) | −0.02 [−0.04; −0.01] | −5.25 | .0093 |

| Daily dose of prandial insulin | 438 | 54.07 (17.06) | −2.00 [−3.61; −0.40] | −3.70 | .0146 | 292 | 55.56 (21.39) | −3.37 [−5.83; −0.90] | −6.07 | .0076 |

| Prandial dose adjusted for body weight (U/kg) | 343 | 0.57 (0.33) | −0.02 [−0.04; −0.01] | −4.04 | .0039 | 225 | 0.60 (0.35) | −0.04 [−0.07; −0.02] | −7.00 | .0009 |

| Total daily dose of insulin | 731 | 71.26 (25.18) | −2.48 [−4.24; −0.71] | −3.48 | .006 | 484 | 73.07 (30.92) | −2.69 [−5.34; −0.04] | −3.68 | .0467 |

| Total daily dose adjusted for body weight (U/kg) | 572 | 0.74 (0.56) | −0.02 [−0.04; −0.01] | −3.24 | .0095 | 374 | 0.77 (0.56) | −0.03 [−0.06; 0.00] | −3.51 | .0619 |

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; LSMeans, least squares means; SD, standard deviation; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; T2DM, type 2 diabetes; U, units.

Data are LSMeans. Multivariate ANCOVA model controlled for: country, age, BMI, gender, diabetes duration, duration of insulin therapy and type of basal injections.

In T2DM, at 6 months, daily basal insulin dose was unchanged; however, daily prandial insulin dose and total daily insulin dose decreased by −2.00 U (−4%) (P = .015) and −2.48 U (−3%) (P = .006), respectively, compared with baseline (Table 2). At 12 months, daily basal insulin dose, daily prandial insulin dose and total daily insulin dose decreased by −1.54 U (−4%) (P = .036), −3.37 U (−6%) (P = .008) and −2.69 U (−4%) (P = .047), respectively, compared with baseline (Table 2). In both T1DM and T2DM, when analysing changes in weight‐adjusted dose (dose divided by body weight), the pattern of changes was the same as that seen for the primary analysis of dose (Table 2).

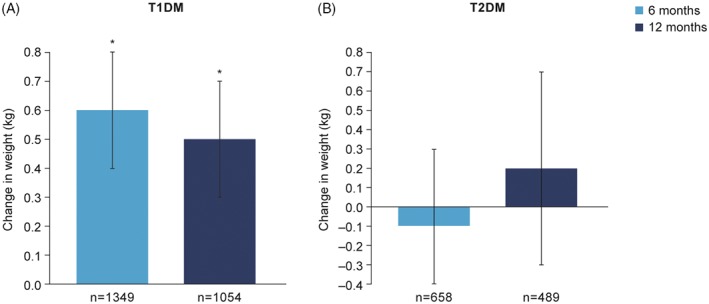

3.5. Body weight

In T1DM, body weight increased by 0.58 [0.41; 0.76] kg at 6 months, compared with baseline (P < .001), and was stable at 12 months (P = not significant vs 6 months) (Figure 3). In T2DM, body weight did not change significantly compared with baseline at either 6 or 12 months (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Change in body weight in patients with A, T1DM and B, T2DM. *P < .001 vs baseline. Data are LSMeans. Multivariate ANCOVA model controlled for: country, age, BMI, gender, diabetes duration, duration of insulin therapy and type of basal injections. Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; BMI, body mass index; LSMeans, least‐squares means; n, number of patients with data at both time points, NS, not significant; T1DM, type 1 diabetes; T2DM, type 2 diabetes

3.6. Real‐world use of IDeg

Fluctuation in blood glucose values (variability) was the primary reason for switching to IDeg (72%, T1DM; 73%, T2DM). The second most common reason for switching was general hypoglycaemia in T1DM (36% of patients), and high basal insulin dose in T2DM (28% of patients) (Figure S1). At 6 months, 6.7% of patients had discontinued IDeg. Among patients with T1DM, “unspecified causes” was the most common reason for discontinuing IDeg (3.0% of patients). The most common reason for patients with T2DM was cost (3.7% of patients) (Figure S2).

4. DISCUSSION

This is the largest study in patients with T1DM or T2DM evaluating the effect of switching to IDeg under conditions of routine care. This retrospective chart review study shows that switching to IDeg from other basal insulins significantly improves glycaemic control and reduces the risk of overall, nocturnal and severe hypoglycaemia.

These results may have been expected, based on the findings of RCTs and recent, small‐scale retrospective observational studies, which have shown similar improvements in clinical outcomes.4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11 A single‐centre study by Evans et al. (n = 51; 35 T1DM, 16 T2DM) assessed the clinical benefits of switching to IDeg in a real‐world population.10 Patients had switched from insulin detemir or insulin glargine U100 to IDeg. After 25.5 ± 6 weeks' mean follow‐up duration, HbA1c was reduced by −5.5 mmol/mol (−0.5%) in patients with T1DM and by −7.7 mmol/mol (−0.7%) in T2DM. Insulin dose increased by 7.1 U and 10.7 U for patients with T1DM and T2DM, respectively. This increase in dose was probably the result of patients being able to titrate effectively, which had not been possible on their previous regimen. Despite the increase in insulin dose, the rate of hypoglycaemic episodes decreased by >90%. Body weight was unchanged.10 In another single‐centre, real‐world study by Landstedt‐Hallin et al. in patients with T1DM (n = 357), HbA1c decreased by −3.3 mmol/mol (−0.3%) after switching to IDeg. In the same study, the insulin dose was reduced by 12% post switch, and there was a 20% reduction in the rate of overall hypoglycaemia, along with a halving of the rate of nocturnal hypoglycaemia.11 These findings are in line with those of our study in which HbA1c was significantly reduced in both T1DM and T2DM patients, bringing patients closer to target HbA1c levels.12, 13 The absolute change in HbA1c in T2DM patients was clinically relevant and is comparable to the improvement observed in patients switching from neutral protamine Hagedorn to insulin glargine U100.14 In T1DM, the decrease in HbA1c vs pre‐switch levels was less marked (−2.2 mmol/mol (−0.2%) reduction; baseline 64 mmol/mol (8.0%)) compared with T2DM; however, in both populations there was a concomitant reduction in the mean risk of hypoglycaemia and total daily insulin dose. It warrants mentioning that this real‐world study did not follow a treat‐to‐target algorithm, hence the explanation for reductions in HbA1c from baseline that are smaller than those observed in phase 3 RCTs. The reasons for switching to IDeg could also explain the difference in HbA1c reduction between T1DM and T2DM patients. Patients with T1DM are more likely to switch to an alternative basal insulin because of high variability in their blood glucose profile, whereas switching in patients with T2DM is typically initiated because HbA1c is above target. Consequently, greater efforts are made to titrate insulin dose in patients with T2DM, leading to a larger reduction in HbA1c compared with T1DM patients. A possible explanation for the reduction in the risk of hypoglycaemia and insulin dose, despite lower HbA1c, is that the flatter time–action profile of IDeg reduces the magnitude and frequency of the blood glucose excursions often seen with other basal insulins. Patients subsequently spend more time with blood glucose in the target range, avoiding the peaks and nadirs associated with high HbA1c and hypoglycaemia, respectively. The small but significant increase in body weight in patients with T1DM was surprising, set against the reduction in insulin dose vs pre‐switch dose. This may reflect changes in patients' diet, activity levels or adherence to the insulin regimen.

Hypoglycaemia has acute medical consequences that include cognitive dysfunction, seizures, increased risk of cardiovascular events and death, but there is also a long‐term impact on diabetes management resulting from the fear of hypoglycaemia, which can reduce patients' adherence to insulin regimens and lead to physicians setting less aggressive blood glucose targets.15, 16, 17 In addition to the physiological and psychosocial burden, hypoglycaemia – and severe events in particular – is a major contributor to healthcare resource utilization and the cost of treating diabetes.18 The large reduction in the risk of hypoglycaemia observed with IDeg in this study indicates that IDeg has the potential to improve glycaemic control and patients' quality of life, and could also play a role in reducing the cost burden of hypoglycaemia.

Another finding of this study that is worthy of note is the reason for discontinuing IDeg. In patients with T1DM, the most common reason for discontinuing treatment was “unspecified” (Figure S2). A large proportion of the patients who discontinued treatment with IDeg were based in Germany where, following a change in reimbursement status, it is no longer marketed. Many of the patients who discontinued treatment for unspecified reasons did so because IDeg was no longer reimbursed.

This study is subject to limitations, including the observational, retrospective design of the study and the absence of a comparator arm, both of which present the possibility of confounding. For example, other factors could contribute to reductions in HbA1c and the risk of hypoglycaemia, including regression to the mean, selection bias in patients switched to IDeg, better management of patients by healthcare professionals after switching to a new basal insulin, including increased compliance with dietary recommendations, and a placebo effect. However, the fact that the effect of IDeg on HbA1C and hypoglycaemia was sustained after 12 months speaks strongly against a non‐pharmacological “new treatment” effect. In addition, the data from this study support those of RCTs that suggest that there is a real pharmacological benefit of switching to IDeg.

Another potential limitation to the study is that hypoglycaemic episodes were recorded by physicians/nurses, an approach that may not capture all events and could vary among sites; however, this should not influence the rate ratio for the pre‐ and post‐switch periods. Furthermore, closer monitoring of patients after switching should mean that more, not fewer, hypoglycaemic events are recorded in the post‐switch period compared with the pre‐switch period, which in turn means that the reduction in hypoglycaemia may be underestimated. Sodium glucose co‐transporter‐2 (SGLT2) inhibitors received marketing approval and became available for prescription during the study period. Co‐use of SGLT2 inhibitors is associated with a lower insulin dose requirement in insulin‐treated patients and there is no inherent risk of hypoglycaemia.19, 20 This could bias the results for patients with T2DM if treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors commenced at the same time the patient switched to IDeg, but this is unlikely because physicians usually avoid initiating these 2 treatments at the same time. At the time of the study, insulin glargine U300 had just been approved (only 1 patient was receiving IGlar U300); therefore, we are unable to draw conclusions on the clinical outcomes for patients switching from insulin glargine U300 to IDeg.

Strengths of this study include the large‐scale, multi‐centre/‐country design, which reduces the effect of local diabetes management on overall clinical outcomes, and the use of real‐world data, which gives a more representative patient population with a higher prevalence of diabetes‐related complications and comorbidities than would be typical for an RCT. Clinicians did not know that patients would be participating in the study at the time of switching, which lowers the risk of bias. The consistency in the direction and magnitude of the results at 6 and 12 months, and in 2 different diseases (T1DM and T2DM), supports the assessment that changes in clinical endpoints are robust and pharmacological in nature. Future investigations would benefit from analysing data from a control group comprised of patients who switched to a different basal insulin analogue and another non‐insulin, blood glucose‐lowering therapy. A longer‐term study of IDeg in clinical practice is needed to confirm that the changes observed in the EU‐TREAT study are maintained beyond 12 months.

In summary, this study demonstrates that switching patients to IDeg from other basal insulins improves glycaemic control and significantly reduces the risk of hypoglycaemia in routine clinical practice. In patients with T1DM, insulin dose requirements were reduced after switching; in patients with T2DM, weight neutrality was observed. These outcomes were consistent at 6 and 12 months after initiation of IDeg.

Supporting information

Table S1. List of Independent Ethics Committees.

Table S2. Oral antidiabetic drugs in type 2 diabetes at baseline.

Table S3. Hypoglycaemia: type 1 diabetes (6 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S4. Hypoglycaemia: type 1 diabetes (12 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S5. Hypoglycaemia: type 2 diabetes (6 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S6. Hypoglycaemia: type 2 diabetes (12 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S7. Proportions of patients experiencing ≥1 hypoglycaemic episode at 6 and 12 months pre‐ and post‐switch by hypoglycaemia classification.

Figure S1. Reasons for patients switching to insulin degludec.

Figure S2. Reasons for discontinuing insulin degludec at 6 months.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the investigators, study staff and patients for their participation. The authors also thank Helge Gydesen, Anne Kaas, Deniz Tutkunkardas and Andrei‐Mircea Catarig (Novo Nordisk) for their review and input to the manuscript, Loes Vanden Eynde (Novo Nordisk) for European project coordination and ICON (Dublin, Ireland) for project management and statistical analyses services. Medical writing and submission support were provided by Paul Tisdale and Daria Renshaw of Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc. This support was funded by Novo Nordisk.

Parts of this study were presented as a poster presentation at the American Diabetes Association, 77th Annual Scientific Sessions, June 9 to 13, 2017, San Diego, California.

Conflict of interest

T. S. has participated in advisory panels for Abbott, Ascensia, Bayer Vital, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck Sharp Dohme (MSD), Novo Nordisk and Sanofi; has received research support from AstraZeneca/Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Becton Dickinson, Eli Lilly, MSD, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi; and has participated in speakers' bureaus for Abbott, AstraZeneca/Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Berlin Chemie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Medtronic, MSD, Novartis, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi. N. T. has participated in advisory panels for Merck Sharp Dohme (MSD), AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, ELPEN, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis, and has received research support from MSD, Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Cilag, GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis. S. T. K. has participated in advisory panels for, and has received lecture honoraria, from Novo Nordisk, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Sanofi, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim and AstraZeneca. A. L. has no conflicts of interest to declare. R. P. has participated in advisory panels for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharp Dohme, Sanofi‐Aventis and Boehringer Ingelheim. T.‐M. P. was an employee of Novo Nordisk Region Europe A/S at the time of this study, and owned shares in the company. M. L. W. is an employee of, and shareholder in, Novo Nordisk A/S. B. S. has participated in advisory panels for AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has received honoraria for lectures from Merck Sharp Dohme, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Author contributions

T. S., N. T., S. T. K., A. L., R. P. and B. S. were investigators in the EU‐TREAT study. T.‐M. P. and M. L. W. contributed to the study design and statistical analysis. All authors discussed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. T. S. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Siegmund T, Tentolouris N, Knudsen ST, et al. A European, multicentre, retrospective, non‐interventional study (EU‐TREAT) of the effectiveness of insulin degludec after switching basal insulin in a population with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:689–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13149

Tra‐Mi Phan ‐ Employee of Novo Nordisk at the time of the study.

Funding information Novo Nordisk

REFERENCES

- 1. Heise T, Hermanski L, Nosek L, Feldman A, Rasmussen S, Haahr H. Insulin degludec: four times lower pharmacodynamic variability than insulin glargine under steady‐state conditions in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:859–864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heise T, Nørskov M, Nosek L, Kaplan K, Famulla S, Haahr HL. Insulin degludec: lower day‐to‐day and within‐day variability in pharmacodynamic response compared with insulin glargine 300 U/mL in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2017;19:1032–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tresiba® . Summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Product_Information/human/002498/WC500138940.pdf. Accessed April 24, 2017.

- 4. Ratner RE, Gough SC, Mathieu C, et al. Hypoglycaemia risk with insulin degludec compared with insulin glargine in type 2 and type 1 diabetes: a pre‐planned meta‐analysis of phase 3 trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies M, Sasaki T, Gross JL, et al. Comparison of insulin degludec with insulin detemir in type 1 diabetes: a 1‐year treat‐to‐target trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18:96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lane WS, Bailey TS, Gerety G, et al. Effect of insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 on hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes: the SWITCH 1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wysham CH, Bhargava A, Chaykin LB, et al. Effect of insulin degludec vs insulin glargine U100 on hypoglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes: the SWITCH 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:45–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marso SP, McGuire DK, Zinman B, et al. Efficacy and safety of degludec versus glargine in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:723–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rothwell PM. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “to whom do the results of this trial apply?”. Lancet. 2005;365:82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Evans M, McEwan P, Foos V. Insulin degludec early clinical experience: does the promise from the clinical trials translate into clinical practice‐‐a case‐based evaluation. J Med Econ. 2015;18:96–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Landstedt‐Hallin L. Changes in HbA1c, insulin dose and incidence of hypoglycemia in patients with type 1 diabetes after switching to insulin degludec in an outpatient setting: an observational study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:1487–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient‐centred approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58:429–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Diabetes Association . Approaches to glycemic treatment. Sec. 7. In standards of medical care in diabetes—2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(suppl 1):S52–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sharplin P, Gordon J, Peters JR, Tetlow AP, Longman AJ, McEwan P. Improved glycaemic control by switching from insulin NPH to insulin glargine: a retrospective observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2009;8:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cryer PE. Hypoglycaemia: the limiting factor in the glycaemic management of type I and type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2002;45:937–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Kruger DF, Travis LB. Correlates of insulin injection omission. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:240–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peyrot M, Barnett AH, Meneghini LF, Schumm‐Draeger P‐M. Insulin adherence behaviours and barriers in the multinational global attitudes of patients and physicians in insulin therapy study. Diabet Med. 2012;29:682–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hex N, Bartlett C, Wright D, Taylor M, Varley D. Estimating the current and future costs of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the UK, including direct health costs and indirect societal and productivity costs. Diabet Med. 2012;29:855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilding JP, Woo V, Rohwedder K, Sugg J, Parikh S, Dapagliflozin Study Group . Dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving high doses of insulin: efficacy and safety over 2 years. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:124–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Neal B, Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, et al. Efficacy and safety of canagliflozin, an inhibitor of sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2, when used in conjunction with insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. List of Independent Ethics Committees.

Table S2. Oral antidiabetic drugs in type 2 diabetes at baseline.

Table S3. Hypoglycaemia: type 1 diabetes (6 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S4. Hypoglycaemia: type 1 diabetes (12 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S5. Hypoglycaemia: type 2 diabetes (6 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S6. Hypoglycaemia: type 2 diabetes (12 months pre‐ and post‐switch).

Table S7. Proportions of patients experiencing ≥1 hypoglycaemic episode at 6 and 12 months pre‐ and post‐switch by hypoglycaemia classification.

Figure S1. Reasons for patients switching to insulin degludec.

Figure S2. Reasons for discontinuing insulin degludec at 6 months.