Abstract

Objectives

To compare the effect of a 6‐month community‐based intervention with that of usual care on quality of life, depressive symptoms, anxiety, self‐efficacy, self‐management, and healthcare costs in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and 2 or more comorbidities.

Design

Multisite, single‐blind, parallel, pragmatic, randomized controlled trial.

Setting

Four communities in Ontario, Canada.

Participants

Community‐dwelling older adults (≥65) with T2DM and 2 or more comorbidities randomized into intervention (n = 80) and control (n = 79) groups (N = 159).

Intervention

Client‐driven, customized self‐management program with up to 3 in‐home visits from a registered nurse or registered dietitian, a monthly group wellness program, monthly provider team case conferences, and care coordination and system navigation.

Measurements

Quality‐of‐life measures included the Physical Component Summary (PCS, primary outcome) and Mental Component Summary (MCS, secondary outcome) scores of the Medical Outcomes Study 12‐item Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐12). Other secondary outcome measures were the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D‐10), Summary of Diabetes Self‐Care Activities (SDSCA), Self‐Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease, and healthcare costs.

Results

Morbidity burden was high (average of eight comorbidities). Intention‐to‐treat analyses using analysis of covariance showed a group difference favoring the intervention for the MCS (mean difference = 2.68, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.28–5.09, P = .03), SDSCA (mean difference = 3.79, 95% CI = 1.02–6.56, P = .01), and CES‐D‐10 (mean difference = −1.45, 95% CI = −0.13 to −2.76, P = .03). No group differences were seen in PCS score, anxiety, self‐efficacy, or total healthcare costs.

Conclusion

Participation in a 6‐month community‐based intervention improved quality of life and self‐management and reduced depressive symptoms in older adults with T2DM and comorbidity without increasing total healthcare costs.

Keywords: type 2 diabetes mellitus, comorbidity, older adults, self‐management, community‐based program

In 2017, 347 million people have diabetes mellitus worldwide, and this is expected to increase by 55% by 2035, with more than 90% of cases being type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1, 2 Older adults have the highest prevalence of T2DM of any age group,3 and comorbidity is common, with more that 40% of individuals with T2DM having 3 or more comorbidities.1, 4 T2DM combined with comorbidity is linked to higher mortality, poorer functionality and greater health service use3, 5, 6 than T2DM alone.

Self‐management interventions, such as those in the U.S. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)7 and the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (FDPS)8, are recommended for people with T2DM because they demonstrate that lifestyle changes are effective and the benefits sustainable.9, 10, 11 These interventions use motivational techniques to improve confidence (self‐efficacy) and education to guide behavior change, but recent trial evidence is mixed. A 2016 systematic review of person‐centered, team‐based interventions found that some studies reported improvements in outcomes and reductions in use and costs, whereas others showed no change.12 Similarly, a 2016 Cochrane review of community‐based interventions targeting multimorbidity (many including T2DM) reported no clear improvements in clinical outcomes, service use, or health behaviors and only modest improvements in mental health outcomes if programs targeted specific risk factors or functional difficulties.13

There is great interest in community‐based programs, because interventions like the DPP and FDPS are clinic based and resource intensive. A systematic review of studies that translated the DPP into primary care, community, and work settings14 concluded that linking programs to existing structures (e.g., YMCA) may enhance adoption, implementation, and sustainability, yet the reliability of studies examining community‐based interventions has been questioned because many studies rely on single‐group designs or small samples,15 and few have included older adults with T2DM and comorbidity.3, 16 With greater risk of geriatric syndromes and comorbidity,17 this medically complex population is difficult to reach, recruit, and retain.18 Consequently, the effectiveness of self‐management programs for this population is uncertain, and more information is needed on effects in subgroups and service costs.

This article presents the results of a trial examining whether a 6‐month self‐management program for older adults with T2DM and multiple (≥2) chronic conditions (MCCs) was more effective in improving health outcomes than usual care. The primary outcome was physical health‐related quality of life (HRQoL); secondary outcomes were mental HRQoL, depressive symptoms, anxiety, self‐efficacy, self‐management, and health service costs. The trial also assessed outcomes for providers, caregivers, and implementation processes and is ongoing in another Canadian province. These analytical results for the Alberta sites will be reported separately.

Methods

Details regarding study design and outcomes for this multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) of community‐dwelling older adults are described in the published study protocol.19 The trial was designed to be pragmatic using the 9 domains of the Pragmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary‐2 tool,20 which includes features such as recruiting clients representative of the population presenting in clinical practice, intervention delivery by clinical practice providers, and intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis. Briefly, the effectiveness of a 6‐month self‐management program, proven feasible in a pilot study,21 was compared with usual community‐based care.

Intervention

Health care in Ontario is a provincial government responsibility according to the Canada Health Act, 1984, which requires that provinces provide medically necessary care at no cost to the individual if the care is provided in a hospital or by a physician but not (necessarily) if care is provided in other settings or by other healthcare providers.22 The Ontario government funds diabetes education centers (DECs), which provide diabetes care at no cost to individuals, including diabetes education, counselling, individual and family support, and guidance in developing life plans to minimize symptoms and delay or prevent onset of complications of diabetes.

An interprofessional team of registered nurses (RNs) and registered dietitians (RDs) from DECs, a program coordinator (PC) from a community partner (YMCA at 3 of 4 sites), and peer volunteers delivered the intervention.19 The program offered up to 3 in‐home visits by the RN, RD, or both; monthly group wellness sessions involving the DEC providers, community partners, and peer volunteers; monthly case conferences involving the RN, RD, and PC; and ongoing nurse‐led care coordination. The principles underlying the program are self‐efficacy, self‐management, holistic care, and individual and caregiver engagement. The individual is a critical member of the care team and is fully engaged in developing and tailoring his or her care plan to meet his or her needs and preferences. The program is client driven and therefore flexible in terms of the delivery of program elements, specific activities emphasized, and dosage. For example, clients can decline one or more in‐home visits or group sessions or choose the DEC instead of their home for the visits.

Interventionists and peer volunteers each attended a 2‐day training session, supported by role‐appropriate and standardized training manuals. Training sessions involved education and role‐playing to enhance motivational interviewing skills and included diabetes education within the context of MCCs. Study investigators conducted monthly outreach meetings with providers and volunteers to discuss study progress, provide feedback and education, and identify and resolve barriers. Study investigators audited visit reports and team meeting records and documents to assess intervention fidelity.

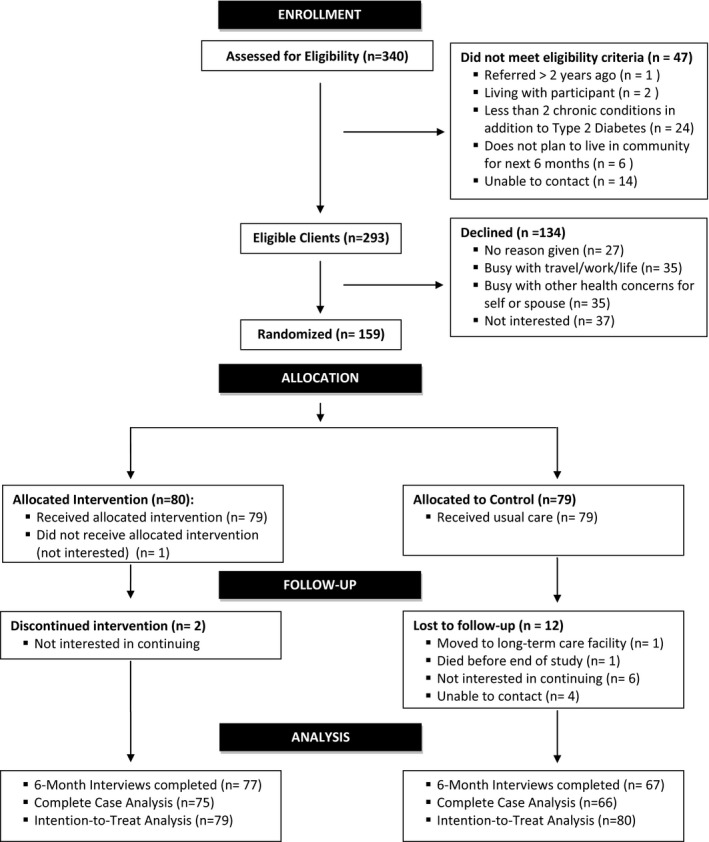

Participants

Participants were clients recently referred to 4 DECs in Ontario, Canada. The study flow chart is shown in Figure 1. Recruitment spanned 8 months (December 2014 to July 2015). Consecutive clients (n = 340) referred to the DECs in the last 2 years were screened for eligibility. Of these, 293 (86%) had MCCs (Supplementary Table S1) and were invited to participate if they were aged 65 and older, able to speak English or provide an interpreter, not planning to leave the community within 6 months, and cognitively intact (Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire score ≥523). Of those eligible, 159 agreed to participate and, after providing written consent, were randomized to the intervention (n = 80) or control (n = 79) group.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

Randomization

Participants were randomly allocated to the 2 groups using a 1:1 ratio. A biostatistician not involved in recruitment generated group allocations using stratified permuted block randomization. Random number sequences were input into a centralized web‐based service (RedCap) that allocated clients (within site) to the 2 groups according to sequence.

Measures

Details regarding design and outcome measures are described in the study protocol.19 HRQoL, mental health, self‐efficacy, and self‐management outcomes were selected based on effects evidence from T2DM self‐management intervention reviews and metaanalyses.24, 25, 26 Trained research assistants obtained outcome data at baseline and 6 months after the intervention.

The 12‐item Medical Outcomes Study Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐12) consists of two HRQoL measures: the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS).27 The primary outcome, physical HRQoL, was measured according to the PCS.27 Secondary outcomes included SF‐12 subdomain and MCS scores,27 depressive symptoms measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D‐10),28 anxiety measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD‐7),29 self‐efficacy measured using the Self‐Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale,30 self‐management activities measured using the Summary of Diabetes Self‐Care Activities (SDSCA) Scale,31 and healthcare use (e.g., physician visits, hospitalizations, home care) measured using the Health and Social Services Utilization Inventory (HSSUI),32, 33 which is a reliable and valid34, 35 self‐report questionnaire that measures the use of health and social services from a societal perspective. Inquiries are restricted to the reliable duration of recall: 6 months for recalling a hospital, emergency department, or physician visit and 2 days for use of a prescription medication.32 A cost analysis intended to inform the broad allocation of resources in the public interest should be conducted from a societal perspective, because this includes potential costs and benefits for all stakeholders.36

Guidelines were available for judging clinical significance for only some study measures. SF‐12 developers suggest a minimally important difference (MID) of 3 for interpreting group mean summary score differences (PCS, MCS) and warn against comparing subdomain scores over time.37 The CESD‐1038 and SDSCA39 do not have established MIDs.

Blinding

Because of the nature of the intervention, it was not feasible to blind participants or providers. To reduce bias, the statistician–analyst and research assistants collecting assessment data were blinded.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was calculated based on the primary outcome measure: PCS. A target sample size of 160 (80 per group) was calculated to ensure 80% power, 0.50 effect size (PCS), 0.05 (two‐sided) alpha, and 20% attrition. Effect sizes and attrition rates were similar to those observed in the pilot study.21

The data are presented as means and standard deviations for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test the differences in outcome variables between the intervention and control groups at 6 months. Separate ANCOVA models were run for each outcome, with the 6‐month outcome as the dependent variable, group (intervention, control) as the independent variable, and the baseline value of the outcomes as the covariate. Statistical tests used a .05 two‐tailed level of significance and 95% confidence intervals. A complete case analysis was performed using only clients with complete outcome data; sample sizes ranged from 136 (CESD‐10) to 141 (SF‐12 outcomes). Multiple imputation is considered the best method for addressing the most common and realistic missing data patterns seen in RCTs.40 We performed multiple imputation (n = 159) using a previously recommended procedure.41

Subgroup analyses were performed to determine whether the effects of the intervention on HRQoL (PCS, MCS) differed according to baseline group. Consistent with subgroup analysis recommendations,42 this work was supplemental and restricted to 5 factors (age, number of comorbid conditions, sex, self‐efficacy, diabetes duration). We hypothesized that the intervention would be less effective in older adults and those with more comorbidities because of the likelihood that they would have more‐complex care needs. We also hypothesized that the intervention would be more effective in men because they are known to engage in fewer self‐management activities and access health services less frequently than women.43 Subgroup differences in the intervention effect were determined based on the significance of the group or subgroup interaction in a regression model including the main effects and interaction term.

Cost analyses were conducted to compare the cost of health service use of the intervention and control groups. The service use that clients reported, using the HSSUI at baseline and 6 months after the intervention, was multiplied by the unit costs for the service to obtain total service costs. Unit costs were obtained from the provincial database, which provides the costs of all services that the publicly funded provincial healthcare system pays for.33, 44 Cost data are often substantially positively skewed (as in this study) and have traditionally been handled using nonparametric methods such as rank‐order statistics.45 We used the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U‐test to evaluate differences in median costs between the two groups.46 We also estimated the program costs and compared total service costs at baseline and 6 months for the two groups. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Tri‐Council Policy Statement, Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.47 Institutional ethics approval was obtained from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#14–486). Written informed consent was obtained from participants before study involvement.

Results

Participants (Baseline)

Table 1 shows participant baseline characteristics. Randomization resulted in no significant group differences. Slightly more than half of participants were female, with approximately 30% aged 65 to 69, 40% aged 70 to 74, and 30% aged 75 and older. Most participants were married, and more than half had annual incomes below $CAD40,000. Participants had an average of 8 comorbidities; more than 75% reported hypertension, 80% reported cardiovascular disease, and 65% reported arthritis. Approximately 35% of participants had been living with T2DM for 5 years or less. Baseline physical functioning scores (43 points) were lower than mental functioning scores (53 points). Mean depressive symptom scores were 5.7 for the intervention group and 4.9 for the control group, below the at‐risk cut‐off of 10 for the CESD‐10,48 with only 5% being at or above the cut‐off. Anxiety scores were 1.3, below the at‐risk threshold of 8 established for the GAD‐7 in primary care,49 with approximately 15% being at or above the cut‐off.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Older Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Multiple Chronic Conditions (n = 159)

| Characteristic | Intervention Group, n = 80 | Control Group, n = 79 |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 46 (57.5) | 43 (54.5) |

| Male | 34 (42.5) | 36 (45.5) |

| Age, n (%) | ||

| 65–69 | 26 (32.5) | 24 (30.4) |

| 70–74 | 32 (40.0) | 31 (39.2) |

| ≥75 | 22 (27.5) | 24 (30.4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married, living together | 53 (66.2) | 44 (55.7) |

| Widowed, divorced, separated | 27 (33.8) | 35 (44.3) |

| Annual income, $CAD, n (%) | ||

| <40,000 | 36 (45.0) | 31 (39.2) |

| ≥40,000 | 30 37.5) | 29 (36.7) |

| Missing | 14 (17.5) | 19 (24.1) |

| Number of chronic conditions, mean ± SDa | 8.4 ± 3.6 | 8.3 ± 3.8 |

| Top 3 chronic conditions, n (%)a | ||

| Hypertension | 60 (75.0) | 64 (81.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 64 (80.0) | 63 (79.7) |

| Arthritis | 55 (68.8) | 51 (64.6) |

| Number of prescription medications, mean ± SD | 8.7 ± 3.8 | 8.5 ± 3.7 |

| Time since diabetes mellitus diagnosis, years | ||

| <5 | 30 (37.5) | 27 (34.2) |

| 5–20 | 31 (38.7) | 34 (43.0) |

| ≥20 | 19 (23.8) | 18 (22.8) |

| 12‐item Medical Outcomes Study Short‐Form Survey score, mean ± SD (range 0–100) | ||

| Physical Component Summary | 42.2 ± 11.6 | 43.2 ± 10.6 |

| Mental Component Summary | 52.8 ± 10.4 | 53.0 ± 9.5 |

| 10‐item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score, mean ± SD (range 0–30)b | 5.7 ± 5.0 | 5.1 ± 4.9 |

| 7‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale score, mean ± SD (range 0–21) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 |

| 6‐item Self‐Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease Scale score, mean ± SD (range 0–10)c | 7.7 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 1.9 |

| Summary of Diabetes Self‐Care Activities Scale score, mean ± SD (range 0–63)d | 38.8 ± 10.8 | 37.7 ± 9.3 |

Excluding index condition (type II diabetes mellitus).

Missing: n = 1 each, intervention and control.

Missing: n = 3, control.

Missing: n = 3 each, intervention and control.

SD = standard deviation.

Attrition

Of 159 study participants, 144 (91%) successfully completed the 6‐month follow‐up. Fifteen participants were lost to follow‐up—a dropout rate of 9%. Most losses (n = 12) were in the control group, with lack of interest being the primary reason (Figure 1). No significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics between dropouts and those remaining in the study at 6 months.

Intervention Dose

Of 80 program participants, 77 (96%) received at least 1 home visit and 67 (84%) attended at least 1 group session. Over the 6 months, participants received an average of 2.6 home visits (offered 3) and attended 4.0 group sessions (offered 6). These results indicate that the majority of program clients were engaged and receptive to the home visits and group sessions. Caregivers were invited to attend the in‐home visits and group sessions. Caregivers for 29 of the 80 program clients (36%) accompanied clients to 1 or more group sessions (none attended in‐home visits).

Intervention Effectiveness

The results of the complete‐case (n = 141) ANCOVA are provided in Table 2. For the primary outcome (PCS), the group difference in mean 6‐month scores adjusted for baseline values was not statistically significant. For the secondary outcomes, there was a significant difference between the intervention and control groups on the SF‐12 general health subdomain (mean difference = 3.11, 95% CI = 0.05–5.71, P = .02) and MCS (mean difference = 2.74, 95% CI = 0.28–5.19, P = .03) and for the SDSCA (mean difference = 3.74, 95% CI = 0.9–6.57, P = .01). These differences favored the intervention group. There was no significant group difference between the intervention and control groups on the CES‐D or GAD‐7 or for self‐efficacy. Multiple imputation results support the complete case findings. The pooled results of 5 imputations showed statistically significant group differences favoring the intervention for the SDSCA and the MCS and general health domain of the SF‐12. Multiple imputation also showed a statistically significantly greater decline in depressive symptoms (CESD‐10) in the intervention group than the control group (mean difference = −1.45, 95% CI = −0.13 to −2.76, P = .03), consistent across 5 imputations and 2 different methods (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 2.

Outcomes and Between‐Group Differences (n = 141)

| Outcome | Intervention | Control | Group Differencea (95% Confidence Interval) | P‐Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 Months | Baseline | 6 Months | |||

| Mean ± Standard Deviation | ||||||

| Health‐related quality of life: SF‐12 (n = 75 intervention, n = 66 control) | ||||||

| Physical function | 44.78 ± 10.61 | 44.57 ± 10.44 | 43.94 ± 10.73 | 44.18 ± 11.44 | −0.15 (−3.00–2.71) | .92 |

| Role physicalb | 43.98 ± 11.55 | 46.07 ± 10.08 | 44.13 ± 11.19 | 44.96 ± 11.02 | 1.19 (−1.60–3.98) | .40 |

| Bodily pain | 45.22 ± 13.33 | 45.58 ± 12.36 | 45.57 ± 11.35 | 46.39 ± 11.11 | −0.57 (−3.36–2.21) | .69 |

| General healthc | 47.99 ± 9.29 | 51.52 ± 9.12 | 49.08 ± 9.23 | 49.05 ± 9.83 | 3.11 (0.50–5.71) | .02 |

| Vitalityc | 49.46 ± 9.63 | 51.95 ± 9.11 | 51.75 ± 10.43 | 50.56 ± 10.39 | 2.61 (−0.10–2.61) | .06 |

| Social function | 45.87 ± 12.65 | 52.51 ± 8.82 | 45.58 ± 13.38 | 50.97 ± 9.66 | 1.50 (−1.51–4.50) | .33 |

| Role emotion | 47.76 ± 12.25 | 49.28 ± 10.55 | 49.67 ± 9.88 | 48.25 ± 11.14 | 1.82 (−1.47–5.11) | .28 |

| Mental healthc | 53.58 ± 10.36 | 54.80 ± 7.81 | 54.56 ± 9.01 | 53.17 ± 8.44 | 2.10 (−0.17–4.37) | .07 |

| Physical Component Summary | 43.31 ± 11.01 | 44.41 ± 10.40 | 42.87 ± 11.16 | 44.02 ± 11.65 | 0.04 (–2.22–2.30) | .97 |

| Mental Component Summaryc | 51.97 ± 10.91 | 55.30 ± 7.83 | 53.86 ± 8.91 | 53.51 | 2.74 (0.28–5.19) | .03 |

| 10‐item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale score (n = 71 intervention, n = 65 control) | 5.50 ± 5.17 | 4.67 ± 4.83 | 5.31 ± 5.11 | 5.71 ± 5.24 | −1.13 (−2.56–0.30) | .17 |

| 7‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale score (n = 77 intervention, n = 66 control) | 2.71 ± 3.48 | 2.34 ± 2.92 | 2.91 ± 3.92 | 2.71 ± 3.27 | −0.29 (−1.18–0.60) | .52 |

| Self‐efficacy: Stanford (n = 75 intervention, n = 64 control) | 7.79 ± 1.95 | 8.27 ± 1.57 | 7.94 ± 1.82 | 8.05 ± 1.45 | 0.29 (−0.13–0.70) | .17 |

| Self‐management: Summary of Diabetes Self‐Care Activities Scale d (n = 75 intervention, n = 64 control) | ||||||

| General dietc | 6.02 ± 1.71 | 6.21 ± 1.20 | 5.77 ± 1.79 | 5.85 ± 1.53 | 0.27 (–0.14–0.69) | .19 |

| Special dietc | 5.19 ± 1.42 | 5.60 ± 1.08 | 4.77 ± 1.51 | 5.00 ± 1.84 | 0.41 (−0.04–0.86) | .07 |

| Exercise | 2.24 ± 2.05 | 2.69 ± 2.04 | 2.17 ± 2.09 | 2.09 ± 1.95 | 0.57 (−0.02–1.15) | .06 |

| Foot care | 3.63 ± 2.38 | 4.11 ± 2.31 | 3.48 ± 2.49 | 3.49 ± 2.48 | 0.59 (−0.20–1.36) | .14 |

| Total | 39.33 ± 9.96 | 42.83 ± 8.52 | 37.13 ± 9.50 | 37.86 ± 11.33 | 3.74 (0.92–6.57) | .01 |

Intervention mean–control mean. Result from analysis of covariance adjusted for baseline values.

One of eight health domains measured in the Medical Outcomes Study 12‐item Shorr‐Form Survey (SF‐12). In two questions, it assesses whether respondents accomplished less because of their physical health and whether their physical health limited their work or activities.

Significant interaction between covariate and outcome. See interaction plots (Supplemental Figure S1) to aid interpretation.

9 of 11 items (2 blood glucose monitoring items excluded).

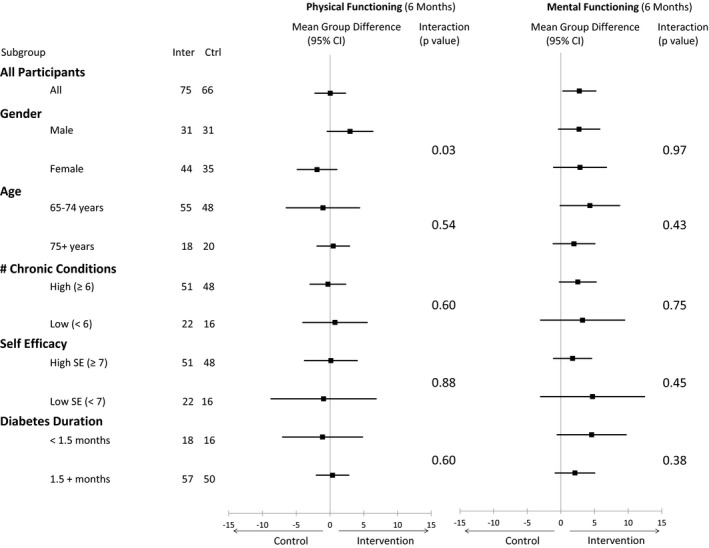

Figure 2 and Supplementary Table S3 provide the results of analyses of the primary outcome (PCS) and secondary outcome (MCS) for 5 subgroups (age, sex, number of chronic conditions, self‐efficacy, diabetes duration). For PCS, one interaction effect was significant (sex, P = .03), which suggests a greater benefit for men than women (as hypothesized). No interaction effects were significant for MCS.

Figure 2.

Mean difference in older adults’ quality of life as measured according to physical functioning (Medical Outcomes Study 12‐item Short‐Form Survey (SF‐12) Physical Component Summary (PCS)) and mental functioning (SF‐12 Mental Component Summary (MCS)) scores from baseline to 6 months for 5 subgroups (age, sex, number of chronic conditions, self‐efficacy, diabetes duration).

Intervention Health Service Costs

Table 3 provides a comparison of health service costs for the intervention and control groups. The median program cost was $CAD1,039.85 (interquartile range $CAD892.71–1,143.10) per study participant (Table 3). As expected, diabetes care costs were higher in the intervention group because of the inclusion of program costs, but significantly lower costs for physician specialist visits offset these costs. There was no difference between groups in change in total costs from baseline to 6 months. For example, cost changes for some services favored the intervention group (family physician and specialist visits, diagnostic tests, supplies and equipment), and others favored the control group (prescription medications, other health professionals, diabetes care). The mean group difference in total cost change excluding hospital costs was $236.92 (favoring the intervention, although not statistically significant).

Table 3.

Health and Social Service Cost Comparison of Intervention and Control Groups (n = 141)

| Service | Intervention | Control | Group Differencea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 Months | Baseline | 6 Months | Z Statistic | P‐Value | |

| $, Median (Interquartile Range) | ||||||

| Family physician visits | 154.40 (77.20–231.60) | 154.40 (97.62–231.60) | 154.40 (97.62–231.60) | 198.33 (154.40–308.80) | −0.18 | .07 |

| Physician specialist | 118.43 (0.00–239.20) | 61.33 (0.00–177.29) | 118.43 (0.00–193.46) | 190.08 (0.00–376.54) | −3.09 | .01b |

| Ambulance and 911 calls | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | −0.09 | .93 |

| Emergency department | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.10 | .92 |

| Home care | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | −1.77 | .08 |

| Diabetes mellitus carec | 95.00 (0.00–150.00) | 1,039.85 (892.71–1,143.10) | 95.00 (50.00–158.25) | 190.00 (50.00–366.00) | 9.60 | <.001d |

| Diagnostic tests | 12.50 (6.30–83.86) | 120.63 (99.18–208.17) | 12.50 (6.30–79.19) | 133.41 (99.18–214.26) | −0.54 | .59 |

| Supplies and equipment | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 14.00 (0.00–111.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 30.00 (12.00–135.00) | −1.38 | .17 |

| Other health professionals | 188.04 (60.00–595.13) | 106.50 (60.00–268.06) | 343.62 (95.30–578.37) | 215.25 (67.31–498.50) | −0.55 | .58 |

| Prescription medications | 900.64 (495.24–1,433.93) | 1,013.94 (537.01–1,626.42) | 1,090.87 (549.51–1,768.95) | 1,166.57 (564.42–1,922.52) | 0.55 | .58 |

| Alternative therapies | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.19 | .85 |

| Hospital | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 | >.99 |

| Total costs | 1,993.30 (1,261.67–3,153.99) | 3,175.06 (2,258.28–4,597.07) | 2,109.33 (1,388.90–3,398.09) | 2,906.11 (2,088.40–4,010.73) | 1.12 | .26e |

Mann‐Whitney U‐test used to determine significance of group differences.

Favors intervention.

Includes program costs for intervention group (training, in‐home visits, group sessions, case conferences).

Favors control.

Total costs excluding hospital costs were examined, but no group differences were observed (z = 1.25, p = .21).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that a 6‐month community‐based program improved mental health HRQoL and self‐management and reduced depressive symptoms in older adults with T2DM and MCC, at no additional cost to society, although no improvements were seen in physical HRQoL. This suggests that mental health changes primarily influenced general HRQoL improvement from this intervention. The reduction in depressive symptoms in the intervention group further supports this. These are important findings given the high rate of depression in this population and its negative effect on diabetes self‐care.

The results of this RCT are encouraging, given the mixed findings in studies reporting the effectiveness of similar interventions. A recent review of integrated care interventions similar to ours found that some studies reported no change in clinical or quality‐of‐life outcomes.12 We found no change in PCS, the primary outcome. Although physical HRQoL did not improve, it may take longer for physical changes to manifest in chronic disease interventions. Reducing depression is an essential step in improving physical outcomes.50 Longer‐term follow‐up may be necessary to see an effect on physical outcomes.

Another review of interventions targeting disease combinations involving mainly diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular disease found that mental health outcomes were among the few to improve, but only for programs that focused on risk factors (e.g., depression) and functional difficulties related to multimorbidity.13 High comorbidity was the norm for our study participants. The high prevalence of comorbidity in older adults is widely recognized,51 and our related work shows that comorbidity in T2DM clients is an important driver of health service use and costs.6 Provider training on MCCs (including depression) was provided in this RCT, in response to requests from providers in our pilot study and their recognition that comorbidity is critical in shaping self‐management.21 Dementia is a comorbidity requiring further study in relation to our program, given that our study participants were cognitively intact. Cognitive ability affects learning, self‐management, and the caregiver's role. Further research is needed in individuals with different cognitive abilities to verify effects and ways to customize the program to address cognitive deficits.

Our finding that the intervention reduced depressive symptoms is also consistent with a recent systematic review showing that self‐management interventions are effective in reducing depression in individuals with T2DM.26 Our program used depression screening and motivational interviewing, which may have led to a reduction in depressive symptoms. There is a current shortage of diabetes educators with psychological skills training,52 yet international studies highlight its importance in addressing depression, which is common in individuals with T2DM and is a major self‐management obstacle.53, 54 Some studies report reduced depressive symptoms for 2 components of our program—nurse case management and motivational interviewing55—and other studies have linked motivational interviewing to better HRQoL and self‐management in individuals with T2DM.56

Further subgroup analysis found that the intervention was more effective in men than women for the primary outcome (PCS). A recent review of differences according to sex in HRQoL found that men benefitted most from self‐management interventions involving peer support, physical activity, and education, suggesting that interventions including these elements may increase men's engagement.43 Our program includes these elements, which may explain our finding. More research is needed to understand the effects of sex, because few studies (including this one) are powered to detect subgroup differences.42

Although our study reported on statistically significant effects, clinical relevance should also be considered. Based on the MID of 3 for the SF‐12 summary scores, the MCS mean group difference we observed of 2.74 (95% CI: 0.28‐5.19) is may be clinically important. Because a MID has not been established for the CESD‐1038 or the SDSCA,39 we cannot comment on the clinical significance of our findings for these outcomes.

Our study reports on a program that can improve population health. At least one‐third of people with diabetes have depressive disorders,57 older adults with T2DM are at greater risk of depression than younger ones,3 and depression in individuals with T2DM is linked to poor self‐care.54 Accordingly, a program that improves mental health can play a central role in management of T2DM. Moreover, management of T2DM outside of hospitals—in outpatient clinics or various community‐based settings—is increasingly common and typically more cost effective and accessible.54 Our program is consistent with this trend and provides access to a team that can screen for depressive symptoms, customize care plans to address mental health and MCC, and facilitate system navigation, ultimately supporting individuals with self‐management and remaining in their homes longer.58

Strengths and Limitations

Our study had a rigorous design. Separate personnel delivered the intervention, performed assessments, and conducted analyses. Recruitment targets were achieved for a complex population typically excluded from trials. Our RCT was highly pragmatic20—capturing individuals representative of those seen in practice and delivering the intervention in a real‐world setting using existing providers. Multiple approaches enhanced intervention fidelity, including provider training, a standardized training manual, and regular meetings between researchers and providers.21 A comprehensive approach was used to examine costs, which is rare in intervention studies.12

We also recognize several limitations. First, we did not measure clinical outcomes (e.g., glycemic control), instead focusing on outcomes that people consider more relevant.59 Studies of similar interventions report improvements in clinical outcomes, and no studies have reported a worsening.12 Second, the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing depressive symptoms emerged from the multiple imputation and not the complete case analysis. Although more research is needed, studies of similar interventions support this finding.13, 26, 55 Third, our intervention is complex, so effects cannot be attributed to specific program components.12, 60 Fourth, absence of established MIDs precluded assessment of the clinical applicability of findings related to depressive symptoms and self‐management. Finally, 54% of eligible clients agreed to participate in the study. Although low participation rates are unsurprising given our complex population, it is possible that participants may differ from individuals who declined.

Conclusions

The rapid increase in the number of community‐dwelling older adults suggests that, without effective interventions, T2DM will become a serious problem that will place increasing burden on healthcare resources. Rising healthcare costs have been attributed to a lack of coordination between healthcare and social providers, which also creates a fragmented healthcare system and often results in inequitable access to services, poor‐quality care, and suboptimal outcomes. Our study provides evidence that a 6‐month community‐based self‐management intervention improves mental health functioning, reduces depressive symptoms, and improves self‐management behavior in older adults with T2DM and MCCs at no additional cost from a societal perspective. These findings underscore the role and value of a coordinated interdisciplinary and intersectoral team in managing T2DM.

Future research should involve a larger pragmatic trial to determine intervention effectiveness in diverse geographic and ethnic settings and in clients with varying degrees of cognitive ability, focus on implementation issues to adapt the program to local contexts, and explore service use to understand changes in use within the context of the intervention. Future trials should also examine intervention sustainability, because many show only short‐term effects. Offering unsustainable interventions is not productive when the chronic conditions they target persist, so future trials should identify sustainability threats and effective ways to overcome them.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Interaction Plots (ANCOVA).

Table S1. List of Comorbidities Included in Study

Table S2. Multiple Imputation Results (n = 159, 5 imputations). Method 1—Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Method 2—Fully Conditional Specification

Table S3. Mean Group Differences (95% CI) for Subgroup Analyses

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff and managers from the Diabetes Education Programs in Ontario (Peterborough Regional Health Centre, Port Hope Community Health Centre, St. Joseph's Health Care, London, Ross Memorial Hospital) and the community‐based organizations in Ontario (Balsillie Family Branch YMCA—Peterborough, YMCA Northumberland, YMCA of Western Ontario—Centre Branch, City of Kawartha Lakes—Parks and Recreation) who provided the intervention. We also thank the interviewers, recruiters, and interventionists who gave their full cooperation so that our study could be conducted.

This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program for Dr. Markle‐Reid. Dr. Griffith is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research New Investigators Award and the McLaughlin Foundation Professorship in Population and Public Health. Our study is also part of a program of research at the Aging Community and Health Research Unit, School of Nursing, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Signature Initiative in Community‐Based Primary Healthcare (http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/43626.html) (Funding Reference TTF 128261) and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care Health System Research Fund Program (Grant 06669).

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest relevant to this study.

Author Contributions: All authors: Study design, discussion and editing. MMR, JP, KDF: Design and implementation of intervention. KAF: First draft of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Sponsor's Role: The study design used an integrated knowledge translation (KT) approach, which resulted in regular KT events with funding agencies to engage them in the research results and identification of policy implications. The funding agencies were not involved in writing the paper or the decision to submit for publication. The authors were independent researchers not associated with the sponsors.

References

- 1. Diabetes Fact Sheet . World Health Organization Media Centre [on‐line]. Available at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/ Accessed March 3, 2017.

- 2. World Health Organization . Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. World Health Organization Department of Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance, 1999. [on‐line]. Available at http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66040 Accessed March 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kirkman M, Briscoe VJ, Clark N et al. Diabetes in older adults: A consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:2342–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sinnige J, Braspenning J, Schellevis F et al. The prevalence of disease clusters in older adults with multiple chronic diseases: A systematic literature review. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e79641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA et al. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA 2007;298:2654–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher K, Griffith L, Gruneir A et al. Comorbidity and its relationship with health service use and cost in community‐living older adults with diabetes: A population‐based study in Ontario, Canada. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2016;122:113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Usitupa M, Tuomilehto J, Puska P. Are we really active in the prevention of obesity and type 2 diabetes at the community level? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2011;21:380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Knowler WC, Barrett‐Connor E, Fowler SE et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. New Engl J Med 2002;346:393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tuomilehto J, Schwarz P, Lindström J. Long‐term benefits from lifestyle interventions for type 2 diabetes prevention. Diabetes Care 2011;34(Suppl 2):S210–S214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yoon U, Kwok LL, Magkidis A. Efficacy of lifestyle interventions in reducing diabetes incidence in patients with impaired glucose tolerance: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Metabolism 2013;62:303–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group , Knowler WC, Fowler SE et al. 10‐year follow‐up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet 2009;374:1677–1686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Busetto L, Luijkx KG, Elissen AM et al. Intervention types and outcomes of integrated care for diabetes mellitus type 2: A systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract 2016;22:299–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith SM, Wallace E, O'Dowd T et al. Interventions for improving outcomes in patients with multimorbidity in primary care and community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;3:CD006560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Whittemore R. A systematic review of translational reseasrch on the Diabetes Prevention Program. Transl Behav Med 2011;1:480–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katula JA, Vitolins MZ, Morgan TM et al. The Healthy Living Partnerships to Prevent Diabetes Study: 2‐year outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2013;44(4 Suppl 4):S324–S332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cruz‐Jentoft AJ, Carpena‐Ruiz M, Montero‐Errasquin B et al. Exclusion of older adults from ongoing clinical trials about type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 6th Ed International Diabetes Federation [on‐line]. Available at https://www.idf.org/e-library/epidemiology-research/diabetes-atlas/19-atlas-6th-edition.html Accessed March 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sakharova OV, Inzucchi S. Treatment of diabetes in the elderly. Addressing its complexities in this high‐risk group. Postgrad Med 2005;118:19–26, 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Markle‐Reid M, Ploeg J, Fraser KD et al. The ACHRU‐CPP versus usual care for older adults with type 2 diabetes and multiple chronic conditions and their family caregivers: Study protocol for a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loudon K, Treweek S, Sullivan F et al. The PRECIS‐2 tool: Designing trials that are fit for purpose. BMJ 2015;350:h2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Markle‐Reid M, Ploeg J, Fisher K et al. The Aging, Community and Health Research Unit‐Community Partnership Program for older adults with type 2 diabetes and multiple chronic conditions: A feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2016;2:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lavis JN, ed. Ontario's Health System: Key Insights for Engaged Citizens, Professionals and Policymakers. Hamilton: McMaster Health Forum, 2016. [on‐line]. Available at https://www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/ontario%27s-health-system Accessed March 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1975;23:433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cochran J, Conn VS. Meta‐analysis of quality of life outcomes following diabetes self‐management training. Diabetes Educ 2008;34:815–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heinrich E, Schaper NC, de Vries NK. Self‐management interventions for type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. European Diabetes Nursing 2010;7:71–76. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cezaretto A, Ferreira SR, Sharma S et al. Impact of lifestyle interventions on depressive symptoms in individuals at‐risk of, or with, type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016;26:649–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12 item short form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MD. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10‐item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D). Arch Intern Med 1999;159:1701–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD‐7) in the general population. Med Care 2008;46:266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL et al. Effect of self‐management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff Clin Pract 2001;4:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self‐care activities measure: Results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care 2000;23:943–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Browne G, Gafni A, Roberts J. Approach to the Measurement of Resource Use and Costs (Working Paper S06–01). Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: McMaster University, System‐Linked Research Unit on Health and Social Service Utilization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Markle‐Reid M, Gafni A, Ploeg J et al. Health and Social Service Utilization Costing Manual: Ontario. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: McMaster University, School of Nursing, Aging, Community and Health Research Unit, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Browne G, Roberts J, Gafni A et al. Economic evaluations of community‐based care: Lessons from twelve studies in Ontario. J Eval Clin Pract 1999;5:367–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Browne G, Roberts J, Gafni A et al. The costs and effects of addressing the needs of vulnerable populations: Results of 10 years of research. Can J Nurs Res 2001;33:65–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Drummond M, Weatherly H, Ferguson B. Economic evaluation of health interventions. BMJ 2008;337:a1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maruish ME, ed. User's Manual for the SF‐12v2 Health Survey, 3rd Ed Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Spinal Cord Injury Research Institute . Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D and CES‐D‐10). SCIRE professional [on‐line]. Available at www.scireproject.com/outcome-measures-new/center-epidemiological-studies-depression-scale-ces-d-and-ces-d-10 Accessed March 3, 2017.

- 39. Oregon Research Institute . Summary of Diabetes Self‐Care Activities (SDSCA): FAQs. Oregon Research Institute [on‐line]. Available at http://www.ori.org/sdsca/faqs Accessed March 3, 2017.

- 40. Thabane L, Mbuagbaw L, Zhang S et al. A tutorial on sensitivity analyses in clinical trials: The what, why, when and how. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013;13:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. He Y. Missing data analysis using multiple imputation: Getting to the heart of the matter. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pocock SJ, McMurray JJ, Collier TJ. Statistical controversies in reporting of clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:2648–2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Galdas P, Fell J, Bower P et al. The effectiveness of self‐management support interventions for men with long‐term conditions: A systematic review and meta analysis. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care . Health Data Branch Web Portal [on‐line]. Available at https://hsim.health.gov.on.ca/hdbportal/ Accessed April 6, 2017.

- 45. Mihaylova B, Briggs A, O'Hagan A et al. Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ 2011;20:897–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McCrum‐Gardner E. Which is the correct statistical test to use? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2008;46:38–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada . Tri‐Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans [on‐line]. Available at www.pre.ethics.gc.ca Accessed November 15, 2016.

- 48. Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB et al. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short‐form of the CES‐D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). Am J Prev Med 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:317–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kolappa K, Henderson DC, Kishore SP. No physical health without mental health: Lessons unlearned? Bull World Health Organ 2013;91:3–3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bayliss EA, Bonds DE, Boyd CM et al. Understanding the context of health for persons with multiple chronic conditions: Moving from what is the matter to what matters. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:260–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Graves H, Garrett C, Amiel SA et al. Psychological skills training to support diabetes self‐management: Qualitative assessment of nurses’ experiences. Prim Care Diabetes 2016;10:376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T et al. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: Results of the Cross‐National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabet Med 2005;22:1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lloyd CE, Gill P, Stone M. Psychological care in a national health service: Challenges for people with diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2013;13:894–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gabbay RA, Añel‐Tiangco RM, Dellasega C et al. Diabetes nurse case management and motivational interviewing for change (DYNAMIC): Results of a 2‐year randomized controlled pragmatic trial. J Diabetes 2013;5:349–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen SM, Creedy D, Lin HS et al. Effects of motivational interviewing intervention on self‐management, psychological and glycemic outcomes in type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 2012;49:637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lloyd CE, Hermanns N, Nouwen A et al. The epidemiology of depression and diabetes In: Katon W, Maj M, Sartorius N, eds. Depression and Diabetes. Chichester: JohnWiley & Sons Ltd, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care . Patients First: A Proposal to Strengthen Patient‐Centred Health Care in Ontario: Discussion Paper. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care, 2015. [on‐line]. Available at http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/news/bulletin/2015/docs/discussion_paper_20151217.pdf Accessed March 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wyatt KD, Stuart LM, Brito JP et al. Out of context: Clinical practice guidelines and patients with multiple chronic conditions: A systematic review. Med Care 2014;52(Suppl 3):S92–S100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moore GF, Audery S, Barker M et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2015;350:h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Interaction Plots (ANCOVA).

Table S1. List of Comorbidities Included in Study

Table S2. Multiple Imputation Results (n = 159, 5 imputations). Method 1—Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Method 2—Fully Conditional Specification

Table S3. Mean Group Differences (95% CI) for Subgroup Analyses