Cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome (CCAS; Schmahmann’s syndrome) is characterized by impaired executive function, linguistic processing, spatial cognition, and affect regulation. Hoche et al. develop and validate a data-driven cognitive screen to detect CCAS resulting from cerebellar lesions. The scale is an important adjunct to rating scales for cerebellar motor ataxia.

Keywords: cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome, rating scale, cognition, behaviour, cerebellum

Abstract

Cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome (CCAS; Schmahmann’s syndrome) is characterized by deficits in executive function, linguistic processing, spatial cognition, and affect regulation. Diagnosis currently relies on detailed neuropsychological testing. The aim of this study was to develop an office or bedside cognitive screen to help identify CCAS in cerebellar patients. Secondary objectives were to evaluate whether available brief tests of mental function detect cognitive impairment in cerebellar patients, whether cognitive performance is different in patients with isolated cerebellar lesions versus complex cerebrocerebellar pathology, and whether there are cognitive deficits that should raise red flags about extra-cerebellar pathology. Comprehensive standard neuropsychological tests, experimental measures and clinical rating scales were administered to 77 patients with cerebellar disease—36 isolated cerebellar degeneration or injury, and 41 complex cerebrocerebellar pathology—and to healthy matched controls. Tests that differentiated patients from controls were used to develop a screening instrument that includes the cardinal elements of CCAS. We validated this new scale in a new cohort of 39 cerebellar patients and 55 healthy controls. We confirm the defining features of CCAS using neuropsychological measures. Deficits in executive function were most pronounced for working memory, mental flexibility, and abstract reasoning. Language deficits included verb for noun generation and phonemic > semantic fluency. Visual spatial function was degraded in performance and interpretation of visual stimuli. Neuropsychiatric features included impairments in attentional control, emotional control, psychosis spectrum disorders and social skill set. From these results, we derived a 10-item scale providing total raw score, cut-offs for each test, and pass/fail criteria that determined ‘possible’ (one test failed), ‘probable’ (two tests failed), and ‘definite’ CCAS (three tests failed). When applied to the exploratory cohort, and administered to the validation cohort, the CCAS/Schmahmann scale identified sensitivity and selectivity, respectively as possible exploratory cohort: 85%/74%, validation cohort: 95%/78%; probable exploratory cohort: 58%/94%, validation cohort: 82%/93%; and definite exploratory cohort: 48%/100%, validation cohort: 46%/100%. In patients in the exploratory cohort, Mini-Mental State Examination and Montreal Cognitive Assessment scores were within normal range. Complex cerebrocerebellar disease patients were impaired on similarities in comparison to isolated cerebellar disease. Inability to recall words from multiple choice occurred only in patients with extra-cerebellar disease. The CCAS/Schmahmann syndrome scale is useful for expedited clinical assessment of CCAS in patients with cerebellar disorders.

Introduction

Cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome (CCAS) is characterized by deficits in executive function, linguistic processing, spatial cognition and affect regulation (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998). It arises from damage to the cognitive cerebellum in the cerebellar posterior lobe (lobules VI, VII, possibly lobule IX), and is postulated to reflect dysmetria of thought analogous to the dysmetria of motor control from damage to the sensorimotor cerebellum in the anterior lobe (lobules III–V) and lobule VIII (Schmahmann, 1991, 1996, 2010; Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009a, 2010; Stoodley et al., 2012, 2016). The CCAS may occur separately or together with the cerebellar motor syndrome and the vestibular syndrome from damage to the flocculonodular lobe, and is the third cornerstone of clinical ataxiology (Schmahmann’s syndrome; Manto and Mariën, 2015).

The defining features of CCAS have been replicated in studies across disease types and in patients of different ages (Malm et al., 1998; Levisohn et al., 2000; Neau et al., 2000; Riva and Giorgi, 2000; Exner et al., 2004; Paulus et al., 2004; Van Harskamp et al., 2005; Schmahmann et al., 2007; Caroppo et al., 2009; Mariën et al., 2009, 2014; Fallows et al., 2011; Tedesco et al., 2011; Wingeier et al., 2011; Hoche et al., 2014; Koziol et al., 2014; Van Overwalle et al., 2015; Adamaszek et al., 2017). Diagnosis presently relies on neuropsychological testing, although the traditional behavioural neurology approach to bedside cognitive testing (Critchley 1953; Heilman and Valenstein, 1979; Mesulam, 1985; Strub and Black, 2000) was the basis for the original diagnosis of cognitive and neuropsychiatric impairment in patients with cerebellar injury and the formulation of the concept of CCAS (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998). There is presently no reliable or validated brief test of mental function to elicit the presence of CCAS in a patient with cerebellar dysfunction analogous to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., 1975) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (Nasreddine et al., 2005), which were developed to detect patients with amnestic and other dementias. There is, therefore, a critical need for a concise screening battery of cognitive tasks proven to be sensitive for the detection of CCAS to determine whether an individual with cerebellar dysfunction has the non-motor manifestations of the cerebellar lesion.

The principal objectives of this study were (i) to examine the neuropsychological profile in a large cohort of patients with lesions of the cerebellum to test and further explore the original conclusions regarding CCAS; and (ii) to investigate the resulting pattern of strengths and deficits to develop a cerebellar cognitive test battery for use in the office or bedside setting sensitive to the deficits of CCAS, and selective enough to differentiate patients from healthy controls. Our secondary objectives were (iii) to evaluate whether the MMSE and MoCA detect cognitive impairment in cerebellar patients; and (iv) whether cognitive performance is different in patients with isolated cerebellar lesions versus those with complex cerebrocerebellar pathology. We took advantage of the inclusion of some patients with advanced cerebrocerebellar pathology to examine (v) whether there are cognitive skills assessed in the neuropsychological test battery or the resulting short test of cerebellar cognition that should raise red flags (Köllensperger et al., 2008) about pathology outside the cerebellum (i.e. what can reasonably be considered non-cerebellar cognition?). Finally, (vi) we validated this new scale in another cohort of cerebellar patients and matched controls.

Subjects and methods

Participants

Adult patients were recruited from the Ataxia Unit of the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Neurology with hereditary or other neurodegenerative ataxias, or acquired injury to the cerebellum. Detailed history was elicited, neurological examination performed, and brain MRI evaluated. Group assignments of patients into isolated cerebellar disease, isolated cerebellar injury and complex cerebrocerebellar disease were based on analysis of genotypes, published pathological features of the spinocerebellar ataxias and related disorders (Koeppen, 2002; Lin et al., 2014, 2016), and expert consensus criteria (Manto et al., 2013). Seventy-seven patients (age range 17–80 years, 42 males, mean education 15.01 years) were included in the study, of whom 36 had disease confined to cerebellum. Demographics are listed in Table 1. Radiographic images representative of every diagnosis encountered in the study are presented in the Supplementary Fig. 1. Fifty-eight healthy controls were matched for age, gender and education (matching age interval 5 years, education intervals ≤12 years, 13–16 years, ≥18 years, gender male or female). Two controls were excluded because of test anxiety, and two because of previously undisclosed attention deficit disorder. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Table 1.

Exploratory cohort: patient diagnoses and demographic features

| Disease entity | Patients n | Gender (F/M) | Age (years, mean) | Education (years, mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated cerebellar pathology | ||||

| Left cerebellar injury (L-haemorrhage, L-tumour, L-SCA stroke) | 3 | 1/2 | 54.6 | 17.0 |

| Posterior fossa injury [medulloblastoma, haemorrhage (n = 2)] | 3 | 1/2 | 28.3 | 15.0 |

| Right cerebellar injury [R-PICA stroke, R-SCA stroke (n = 2)] | 3 | 2/1 | 43.0 | 16.0 |

| Post-infectious cerebellitis | 1 | 1/0 | 33.0 | 12.0 |

| Non-progressive isolated cerebellar ataxia | 2 | 1/1 | 19.0 | 13.0 |

| SCA5 | 1 | 0/1 | 56.0 | 16.0 |

| SCA6 | 6 | 3/3 | 61.7 | 15.2 |

| SCA8 | 4 | 3/1 | 57.5 | 15.0 |

| ARCA-1 | 3 | 1/2 | 50.8 | 15.1 |

| EA-2 | 2 | 1/1 | 23.5 | 13.0 |

| ILOCA | 8 | 3/5 | 47.9 | 15.0 |

| Complex cerebro-cerebellar pathology | ||||

| Cerebellar and brainstem haemorrhage | 2 | 1/1 | 64.0 | 18.0 |

| Complex cerebrocerebellar degeneration with gene variantsa | 2 | 1/1 | 58.0 | 14.3 |

| Pontine cavernous malformation | 1 | 1/0 | 45.0 | 14.0 |

| AOA2 | 1 | 1/0 | 20.0 | 14.0 |

| Friedreich’s ataxia | 2 | 0/2 | 41.5 | 16.0 |

| SCA1 | 7 | 3/1 | 59.4 | 14.3 |

| SCA2 | 5 | 2/3 | 54.5 | 14.8 |

| SCA3 | 12 | 6/6 | 56.3 | 14.6 |

| SCA7 | 2 | 0/2 | 62.0 | 16.0 |

| SCA17 | 1 | 1/0 | 48.0 | 16.0 |

| MSA-C | 6 | 3/3 | 57.3 | 14.5 |

Seventy-seven patients were investigated (isolated cerebellar pathology, n = 36; complex cerebrocerebellar pathology, n = 41).

AOA2 = ataxia oculomotor apraxia type 2; ARCA-1 = autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 1, DRPLA = dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy; EA-2 = episodic ataxia type 2; ILOCA = idiopathic late onset cerebellar ataxia; L = left; MSA-C = multiple system atrophy of the cerebellar type; PICA = posterior inferior cerebellar artery; R = right, s/p = status post; SCA = spinocerebellar ataxia; SCA stroke = infarction in the territory of the superior cerebellar artery.

aComplex cerebrocerebellar degeneration with gene variant: one patient with late onset cerebellar ataxia with white matter hyperintensities and mutational variant in senataxin (SETX) gene; one with late onset cerebellar ataxia, peripheral motor neuropathy and variant X-linked recessive ATP2B3 gene.

Cognitive assessment

Neuropsychological assessment comprised standard tests from widely-used neuropsychological test batteries (e.g. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales, WAIS; Wechsler, 2008) and experimental tasks derived from functional neuroimaging studies showing cerebellar activation (e.g. verb for noun task; Fiez, 1996). Patient performance was compared to standard norms and healthy controls. Supplementary Table 2 lists the tests administered and the domains they are thought to represent. Some tests tap functions that cover more than one domain, as exemplified by phonemic and semantic fluency, which are language tasks that also reflect executive search functions and semantic memory (Shao et al., 2014).

Neuropsychiatric assessment

In our earlier analysis that introduced the concept of the neuropsychiatry of the cerebellum, patients demonstrated, or family members reported, neuropsychiatric phenomena that were categorized according to five domains of behaviour—attentional control, emotional control, autism spectrum, psychosis spectrum, and social skill set (Schmahmann et al., 2007). Within each of these five domains, symptoms were further grouped according to hypermetric/overshoot/positive and hypometric/undershoot/negative symptoms (Supplementary Table 3). Based on this approach, we developed a novel test instrument, the Cerebellar Neuropsychiatric Rating Scale (CNRS) (Daly et al., 2016), which we used in this study. The CNRS was completed by first degree relatives of the patients and healthy controls. It was complemented by use of the Frontal System Behavior Scale (FRSBE) (Grace et al., 1999) and the Social and Communication Disorder Checklist (SCDC) (Skuse et al., 1997) (Supplementary Table 2).

Neurological examination and assessment of ataxia severity

A comprehensive medical and neurological history and examination was documented for every patient. The cerebellar motor syndrome was evaluated, and ataxia severity was assessed by means of the Brief Ataxia Rating Scale (BARS) (Schmahmann et al., 2009; Supplementary Table 4). This clinical score assesses the five cardinal motor manifestations of the cerebellar motor syndrome, namely, gait, lower extremity and upper extremity dysmetria, dysarthria, and oculomotor abnormalities. The maximum severity score is 30: a normal exam scores 0, mild cerebellar motor syndrome 1–9, moderate cerebellar motor syndrome 10–20, and severe cerebellar motor syndrome >20. Motor performance was also evaluated using 25-foot timed walk and 9-Hole Pegboard Test (9HPT; Mathiowetz et al., 1985).

Data analysis

Analysis of cognitive performance in comparison to standard norms and controls

Thirty-six tests were administered [e.g. Delis-Kaplan-Executive Function System (D-KEFS)], providing 71 measures (e.g. set loss errors within D-KEFS), each of which was scored (Table 2). Behavioural data were analysed using SSPS v21 (SSPS Inc.). All tests were administered in their English version, and USA reference norms were used for standard tests. Raw scores were converted to z-scores measuring deviation from the mean to compare all measures on a common scale. Z-scores were calculated using normative data for standardized tests, or control data from our study, e.g. for the oral sentence production test. Each patient was then matched with a group of controls of the same gender and similar age and years of education. A multivariate comparison between patients and controls within each cognitive domain was performed using Hotelling’s T square test (Hotelling, 1931). This was followed by one-tailed paired Student’s t-test for each individual test. Tests that were not significantly different between patients and controls were excluded from further analysis. Differences in cognitive performance between patient groups (complex cerebrocerebellar disease, isolated cerebellar disease, isolated cerebellar injury) were analysed using one-way ANOVA.

Table 2.

Performance of patients and controls on tests of cognitive and emotional processing

| Hotelling's T square F | Hotelling's T square P | Patients | Controls | One tailed paired t-test | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | z | Raw | z | t | df | p | |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||

| EXECUTIVE FUNCTION TESTS | |||||||||||||

| Trails A (s) | 20.535 | 0.000 | 51.65 | 23.14 | −2.29 | 2.94 | 24.55 | 5.47 | 0.88 | 0.72 | −8.133 | 62 | 0.000 |

| Trails B (s) | 124.07 | 79.99 | −6.72 | 24.73 | 57.29 | 15.64 | 0.58 | 0.9 | −6.535 | 62 | 0.000 | ||

| Trails B − Trails A (s) | 60.19 | 65.13 | −1.11 | 3.22 | 32.74 | 13.29 | −0.3 | 0.72 | −2.156 | 76 | 0.017 | ||

| Category switching accuracy (TC) | 10.25 | 3.3 | −0.49 | 1.15 | 13.82 | 1.45 | 0.78 | 0.51 | −7.235 | 49 | 0.000 | ||

| Category switching set loss (TM) | 0.6 | 1.08 | 0.12 | 1.15 | 0.34 | 0.54 | −0.16 | 0.57 | 1.692 | 56 | 0.048 | ||

| Total D-KEFS set loss (TM) | 1.55 | 1.61 | 0.21 | 0.69 | 0.95 | 1.6 | 0.61 | 0.49 | −3.675 | 49 | 0.001 | ||

| D-KEFS repetition errors (TM) | 1.45 | 1.82 | 0.27 | 0.75 | 1.76 | 1.26 | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.258 | 49 | 0.399 | ||

| Letter-number sequencing (TS/2) | 0.97 | 0.89 | −0.55 | 1.14 | 1.19 | 0.65 | −0.26 | 0.83 | −2.012 | 66 | 0.024 | ||

| Letter-number sequencing time (s) | 83.31 | 30.15 | 0.91 | 1.36 | 63.75 | 16.03 | 0.03 | 0.72 | 3.702 | 45 | 0.001 | ||

| Go/No-go Test (TS/2) | 1.09 | 0.87 | −1.41 | 1.75 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.03 | 0.61 | −6.381 | 63 | 0.000 | ||

| Go/No-go Test omissions (TM) | 0.04 | 0.28 | n.a. | n.a. | 0 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | 1 | 51 | 0.161 | ||

| Go/No-go Test commissions (TM) | 1.21 | 1.23 | 3.16 | 3.59 | 0.1 | 0.15 | −0.1 | 0.45 | 6.55 | 51 | 0.000 | ||

| VERBAL MEMORY TESTS | |||||||||||||

| Word immediate recall (TS/5) | 33.025 | 0.000 | 4.88 | 0.4 | −0.7 | 2.94 | 4.94 | 0.16 | −0.28 | 1.18 | −1.134 | 68 | 0.131 |

| Word delayed recall (TS/15) | 12.09 | 3.33 | −1.17 | 2.2 | 13.8 | 0.73 | −0.03 | 0.48 | −3.987 | 68 | 0.000 | ||

| Verbal paired associates - I (TS/32) | 16.89 | 9.52 | 0.08 | 1.19 | 23.03 | 2.98 | 0.78 | 0.49 | −4.354 | 59 | 0.000 | ||

| Learning slope | 2.48 | 2.8 | −0.52 | 1.06 | 4.29 | 1.24 | 0.18 | 0.56 | −4.304 | 59 | 0.000 | ||

| Verbal paired associates - II (TS/8) | 5.46 | 2.63 | 0.13 | 1.02 | 7.28 | 0.64 | 0.81 | 0.4 | −4.683 | 58 | 0.000 | ||

| WORKING MEMORY TESTS | |||||||||||||

| DSF (TS/16) | 106.353 | 0.000 | 9.94 | 2.38 | −0.08 | 0.95 | 11.79 | 1.82 | 0.47 | 0.51 | −4.698 | 60 | 0.000 |

| Longest DSF (TS/9) | 6.25 | 1.19 | −0.77 | 0.91 | 7.29 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.69 | −5.7 | 62 | 0.000 | ||

| DSB (TS/16) | 7.81 | 2.16 | −0.25 | 0.87 | 11.36 | 2.09 | 1.12 | 0.79 | −9.408 | 59 | 0.000 | ||

| Longest DSB (TS/8) | 4.56 | 1.13 | −1.1 | 0.72 | 6.2 | 1.05 | −0.05 | 0.67 | −8.541 | 61 | 0.000 | ||

| Months backwards (TS/1) | 0.87 | 0.38 | −0.47 | 1.94 | 0.97 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.71 | −1.997 | 68 | 0.025 | ||

| Months backwards time (s) | 18.55 | 9.79 | 0.64 | 1.22 | 13.63 | 5.45 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 2.515 | 46 | 0.008 | ||

| LINGUISTIC TESTS | |||||||||||||

| Production of Derived Words (TS/5) | 25.002 | 0.000 | 4.72 | 0.69 | −1.72 | 4.57 | 5 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.25 | −2.694 | 45 | 0.005 |

| Oral Sentence Production (TS/20) | 19.26 | 1.37 | −0.38 | 1.47 | 19.72 | 0.53 | 0.12 | 0.56 | −1.982 | 37 | 0.028 | ||

| Word Repetition (TS/4) | 3.94 | 0.25 | −0.3 | 1.71 | 4 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.11 | −1.675 | 46 | 0.051 | ||

| Verb for Noun (TS/17) | 12.72 | 3.25 | −6.05 | 5.37 | 16.62 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.62 | −8.342 | 49 | 0.000 | ||

| Pseudoword Decoding at 60 s (TS/52) | 40.27 | 8.92 | −1.55 | 2.24 | 44.71 | 2.84 | −0.44 | 0.71 | −4.153 | 45 | 0.000 | ||

| Pseudoword Decoding at 30 s (TS/52) | 22.6 | 6.67 | −1.55 | 1.04 | 28.98 | 4.5 | −0.55 | 0.7 | −6.015 | 41 | 0.000 | ||

| Word Stem Completion (TS/22) | 21.27 | 1.11 | −1.67 | 3.15 | 21.96 | 0.15 | 0.28 | 0.42 | −4.272 | 48 | 0.000 | ||

| Naming (TS/3) | 2.88 | 0.4 | n.a. | n.a. | 3 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | −1.955 | 39 | 0.029 | ||

| Phonemic fluency (TC) (F,A,S words in 3 min) | 32.3 | 12.66 | −0.51 | 1.29 | 50.04 | 6.75 | 1.27 | 0.64 | −8.434 | 49 | 0.000 | ||

| F-letter phonemic fluency (TC) (/1 min) | 10.90 | 4.82 | −0.96 | 0.83 | 16.20 | 2.75 | −0.05 | 0.48 | −7.308 | 59 | 0.000 | ||

| A-letter phonemic fluency (TC) (/1 min) | 9.5 | 4.42 | −1.27 | 0.94 | 15.40 | 2.72 | −0.01 | 0.58 | −9.009 | 59 | 0.000 | ||

| S-letter phonemic fluency (TC) (/1 min) | 11.48 | 4.75 | −1.23 | 0.85 | 18.38 | 2.63 | 0.01 | 0.47 | −10.891 | 59 | 0.000 | ||

| Semantic fluency (TC) (Animals and Boys’ names in 2 min) | 32.82 | 8.54 | −0.7 | 1.19 | 45.61 | 6.27 | 1.02 | 0.63 | −8.335 | 49 | 0.000 | ||

| Animals semantic fluency (TC) (/1 min) | 17.06 | 5.08 | −0.91 | 0.80 | 22.29 | 3.88 | −0.09 | 0.61 | −6.306 | 59 | 0.000 | ||

| Boys’ names fluency (TC) (/1 min) | 15.85 | 4.20 | −0.99 | 0.64 | 22.34 | 4.25 | 0.00 | 0.65 | −8.467 | 58 | 0.000 | ||

| VISUAL-SPATIAL ABILITY TESTS | |||||||||||||

| Star (TS/1) | 29.917 | 0.000 | 0.92 | 0.27 | −0.45 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0.14 | 0 | −2.313 | 61 | 0.012 |

| Pentagon (TS/1) | 0.94 | 0.25 | −0.33 | 1.25 | 0.97 | 0.12 | −0.17 | 0.6 | −1.12 | 61 | 0.134 | ||

| Cube (TS/2) | 1.52 | 0.72 | −0.91 | 1.43 | 1.93 | 0.13 | −0.1 | 0.26 | −4.442 | 61 | 0.000 | ||

| Clock (TS/5) | 4.39 | 0.93 | −0.72 | 1.47 | 4.75 | 0.56 | −0.15 | 0.88 | −2.97 | 58 | 0.002 | ||

| JLO (TS/15) | 11.57 | 3.49 | 0.13 | 1.07 | 13.08 | 1.58 | 0.57 | 0.42 | −3.233 | 58 | 0.001 | ||

| ABSTRACT REASONING TESTS | |||||||||||||

| Addition (TS/6) | 34.577 | 0.000 | 5.48 | 0.78 | −0.29 | 1.19 | 5.77 | 0.36 | 0.15 | 0.55 | −2.613 | 62 | 0.006 |

| Subtraction (TS/6) | 5.05 | 1.05 | −0.97 | 1.76 | 5.69 | 0.4 | 0.11 | 0.67 | −4.387 | 62 | 0.000 | ||

| Similarities (TS/36) | 22.33 | 6.68 | −0.38 | 0.98 | 28.09 | 2.95 | 0.73 | 0.6 | −7.032 | 58 | 0.000 | ||

| Cognitive estimation (TS/4) | 3.51 | 0.56 | −3.27 | 3.89 | 3.99 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.45 | −5.291 | 38 | 0.000 | ||

| BEDSIDE TESTS OF OVERALL COGNITIVE FUNCTION | |||||||||||||

| MMSE (TS/30) | 0.480 | 0.621 | 28.7 | 1.25 | −0.05 | 0.78 | 28.46 | 2.86 | −0.26 | 1.87 | 0.156 | 34 | 0.439 |

| Planning (TS/2) | 1.92 | 0.27 | n.a. | n.a. | 2 | 0 | n.a. | n.a. | −1.781 | 37 | 0.042 | ||

| ATTENTION AND VIGILANCE TESTS | |||||||||||||

| DSF (TS/16) | 87.948 | 0.000 | 9.94 | 2.38 | −0.08 | 0.95 | 11.79 | 1.82 | 0.47 | 0.51 | −4.698 | 60 | 0.000 |

| Longest DSF (TS/9) | 6.25 | 1.19 | −0.77 | 0.91 | 7.29 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.69 | −5.7 | 62 | 0.000 | ||

| Vigilance (TS/1) | 0.91 | 0.29 | −0.23 | 1.45 | 1 | 0 | 0.17 | 0 | −1.776 | 41 | 0.042 | ||

| FRSBE | |||||||||||||

| Total score (self rating) (TS/255) | 24.517 | 0.000 | 99.19 | 23.71 | 1.21 | 0.95 | 73.69 | 9.11 | −0.23 | 0.67 | 9.908 | 54 | 0.000 |

| Apathy (self rating) (TS/85) | 31.95 | 8.95 | 1.2 | 1.12 | 22.15 | 3.16 | −0.22 | 0.67 | 7.985 | 54 | 0.000 | ||

| Disinhibition (self rating) (TS/85) | 29.4 | 8.5 | 0.64 | 1.24 | 23.89 | 3.42 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 3.567 | 54 | 0.001 | ||

| Dysexecutive (self rating) (TS/85) | 39.79 | 9.63 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 27.61 | 4.24 | −0.27 | 0.7 | 8.823 | 54 | 0.000 | ||

| Total score (family rating) (TS/255) | 98.02 | 29.66 | 1.13 | 1.24 | 73.21 | 11.08 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 5.465 | 38 | 0.000 | ||

| Apathy (family rating) (TS/85) | 32.37 | 9.92 | 1.35 | 1.07 | 22.14 | 3.77 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 6.731 | 38 | 0.000 | ||

| Disinhibition (family rating) (TS/85) | 27.41 | 11.4 | 0.51 | 1.36 | 22 | 2.65 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 2.442 | 38 | 0.010 | ||

| Dysexecutive (family rating) (TS/85) | 39.73 | 12.68 | 1.06 | 1.22 | 29.32 | 6.28 | 0.28 | 0.95 | 4.18 | 38 | 0.000 | ||

| SOCIAL COMMUNICATION DISORDERS CHECKLIST | |||||||||||||

| Total (TS/24) | n.a. | n.a. | 6.39 | 5.77 | 0.88 | 1.45 | 2.79 | 2.39 | −0.03 | 0.6 | 4.086 | 39 | 0.000 |

| CEREBELLAR NEUROPSYCHIATRIC SCALE | |||||||||||||

| Social skill negative (TS/12) | 5.329 | 0.000 | 2.08 | 2.30 | 0.80 | 1.54 | 0.79 | 0.89 | −0.06 | 0.60 | 3.138 | 38 | 0.002 |

| Social skill positive (TS/12) | 3.08 | 2.49 | 1.36 | 1.83 | 1.32 | 1.10 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 3.842 | 38 | 0.000 | ||

| Emotion regulation negative (TS/12) | 3.40 | 2.48 | 1.85 | 1.91 | 0.97 | 1.36 | −0.02 | 1.05 | 5.327 | 39 | 0.000 | ||

| Emotion regulation positive (TS/12) | 3.18 | 2.40 | 1.52 | 2.02 | 1.54 | 0.80 | 0.14 | 0.67 | 3.982 | 39 | 0.000 | ||

| Autism spectrum negative (TS/6) | 1.72 | 1.39 | 1.41 | 1.66 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.09 | 0.74 | 4.713 | 38 | 0.000 | ||

| Autism spectrum positive (TS/6) | 0.69 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 1.11 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.77 | 1.241 | 35 | 0.112 | ||

| Psychosis spectrum negative (TS/9) | 2.28 | 2.32 | 1.57 | 2.16 | 0.62 | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 4.328 | 38 | 0.000 | ||

| Psychosis spectrum positive (TS/9) | 0.87 | 1.13 | 2.63 | 3.81 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 1.03 | 3.6 | 38 | 0.001 | ||

| Attention spectrum negative (TS/12) | 4.37 | 3.39 | 0.78 | 1.53 | 3.69 | 2.24 | 0.47 | 1.01 | 1.076 | 42 | 0.144 | ||

| Attention spectrum positive (TS/12) | 3.40 | 2.31 | 0.44 | 1.22 | 2.86 | 1.60 | 0.16 | 0.84 | 1.215 | 42 | 0.116 | ||

Multivariate analysis of the difference in means of each measure between patient groups and controls using Hotelling’s t-square test followed by Student’s t-tests (Hotelling, 1931). Notice that all test domains revealed significant Hotelling’s F-values except for short bedside tests of cognitive function (MMSE). Tests that were included in the CCAS/Schmahmann scale are highlighted in bold.

n.a. = not available for statistical reasons; TC = total correct responses; TM = total number of mistakes; TS/x = total score out of a maximum score of x.

Development of the cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale

To develop the CCAS scale the data were analysed in the following manner:

Since some patients were unable to complete all tests because of fatigue or time constraints, data were analysed only for those missing <15% of the test items. We excluded tests in which the difference between mean raw scores of patients and controls reached significance but the absolute value difference was not sufficient to allow for derivation of a clear diagnostic cut-off (e.g. months backwards raw score, Table 2).

The remaining tests were ranked by group differences in mean z-scores. From this ranking, tests were selected that met the a priori requirement representing the core CCAS domains—executive, linguistic, visual spatial, and affective.

Tests inappropriately lengthy for a screening instrument were excluded. These included tests for which the number of items could not be meaningfully reduced, e.g. verb for noun generation; or those requiring repeated administration across a delay of >10 min, e.g. verbal paired associates delayed recall.

A threshold (or cut-off) was then applied to maximize selectivity to prevent diagnosing controls as patients. A secondary aim was to maintain reasonable sensitivity, i.e. detecting the deficits that would indicate that a patient belongs in the patient group. We emphasized selectivity in determining thresholds to prevent overly optimistic sensitivity. Raw scores of individual controls were used to calculate cut-offs.

A final item in the scale captures subjective assessment of affective range, derived from the CNRS questions that survived into the final rank order of cumulative diagnosis.

We then used Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach, 1951), a measure of internal consistency, to assess the inter-relatedness of the items within the test, i.e. whether all test items in the scale measure the same concept—in this case, the same cognitive domain. Using this coefficient of inter-item correlations, Cronbach α ≥ 0.7 represents acceptable internal consistency, ≥0.8 is good and ≥0.9 is excellent. A Cronbach α ≤ 0.6 is poor (Cronbach, 1951; Nunnaly, 1978; Loewenthal, 2004).

Validation of the cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale

The resulting novel scale was then validated in 39 new patients with cerebellar diseases (Table 3) and 55 healthy control subjects.

Table 3.

Validation cohort: patient diagnoses and demographic features

| Disease entity | Patients n | Gender (F/M) | Age (years, mean) | Education (years, mean) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated cerebellar pathology | ||||

| Right cerebellar infarction s/p meningioma resection | 1 | F | 68 | 16 |

| Spontaneous large R>L and midline cerebellar haemorrhage | 1 | F | 30 | 18 |

| Ischaemic cerebellar infarction–L anterior lobe and lobule VI; R hemispheric lobules VI and VII; L. paramedian pons | 1 | M | 47 | 18 |

| Midline and left cerebellar hemisphere infarction s/p partial cerebellar resection | 1 | F | 59 | 16 |

| Midline and bilateral paramedian cerebellar encephalomalacia s/p pineal gland resection | 1 | M | 42 | 18 |

| Schizoaffective disorder exacerbated by L-PICA infarction | 1 | M | 32 | 16 |

| Cerebellar AVM with L-cerebellar haemorrhage | 1 | M | 62 | 16 |

| L-PICA stroke | 1 | M | 61 | 12 |

| Bilateral PICA stroke | 1 | M | 65 | 16 |

| Residual features of remote rhombencephalitis | 1 | F | 56 | 14 |

| SCA6 | 6 | 2F/4M | 68.5 | 16.5 |

| SCA6 and 8 (CAG expansions in both) | 1 | F | 69.1 | 16 |

| SCA8 | 1 | M | 47 | 18 |

| SCA28 | 1 | F | 53 | 12 |

| Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, gene negative | 2 | 1F/1M | 53.5 | 16.5 |

| ARCA-1 | 2 | 1F/1M | 43.5 | 15 |

| Complex cerebro-cerebellar pathology | ||||

| SCA1 | 4 | 1F/3M | 42 | 16.5 |

| SCA2 | 1 | F | 49 | 16 |

| SCA3 | 3 | 2F/1M | 55.3 | 14 |

| DRPLA | 1 | M | 61 | 18 |

| Fragile X tremor associated ataxia syndrome | 1 | M | 75 | 12 |

| SCA and sensory neuropathy/neuronopathy | 1 | M | 67 | 18 |

| Spastic ataxia | 1 | M | 54 | 12 |

| Gordon Holmes syndrome | 1 | M | 31 | 12 |

| Progressive ataxia with palatal tremor | 1 | F | 69 | 18 |

| Sagging brain syndrome | 1 | F | 53 | 16 |

| MSA-C | 1 | M | 56 | 12 |

Thirty-nine patients not previously tested were investigated. ARCA-1 = autosomal recessive cerebellar ataxia type 1; AVM = arteriovenous malformation; DRPLA = dentatorubro pallidoluysian atrophy; L = left; MSA-C = multiple system atrophy of the cerebellar type; PICA = posterior inferior cerebellar artery; R = right; s/p = status post; SCA = spinocerebellar ataxia.

Results

Analysis of cognitive performance in comparison to standard norms and controls

Performance on current brief tests of cognition

On the MMSE, patients and controls tested within the normal range (≥25; Folstein et al., 1975). Patient mean = 28.70, standard deviation (SD) 1.25; control mean 29.56, SD 0.72, not significant (Supplementary Table 5).

On the MoCA, mean performance of both the patient and control groups was in the normal range, i.e. ≥26. This result obscures the finding that patient mean scores (26.45, SD 2.52) were lower than control mean scores (28.77, SD 1.22, P < 0.001), that patients were impaired on a number of subscores within the MoCA battery (Supplementary Table 5), and that of the 35 patients who completed all MoCA items, six scored ≤25. Further, some patients passed selected MoCA tests when MoCA cut-offs were applied but were impaired compared to controls when the tests were administered as designed and normed on standard tests. This is exemplified by the full Trails B minus Trails A test, and by the digit span task where patients exceeded MoCA normal thresholds (five digits forwards, three backwards) but were significantly impaired compared to controls with more rigorous tests (Table 2).

Confirmation of CCAS in cerebellar patients

Patients demonstrated executive, linguistic, visual spatial and affective impairments, the defining characteristics of CCAS.

Executive function

Standard neuropsychological testing (WAIS-IV; Wechsler, 2008) revealed that cerebellar patients were impaired compared to controls on Trails A (P < 0.001) and Trails B (P < 0.001). Trails B produced more pronounced deficits than Trails A (Trails B − Trails A, P = 0.017) indicating difficulties with cognitive set shifting. Patients experienced impaired verbal cognitive set shifting as measured by category switching tasks: the fruit-furniture naming test in the D-KEFS (Delis et al., 2001) showed lower accuracy (P < 0.001) and more set loss errors (P < 0.048), as did letter number sequencing with more set loss errors (P < 0.024) and slowed overall cognitive processing time (P < 0.001).

The letter number sequencing test also evaluates verbal working memory. Deficits in verbal working memory were further substantiated by the standard version of the digit span task (WAIS-IV) including impairments on the forward digit span, a measure of attention, [Digit Span Forwards (DSF), P < 0.001] and even more affected on the reverse digit span, a measure of verbal working memory [Digit Span Backwards (DSB), P < 0.001] (Wechsler, 2008).

The go/no-go task was impaired because of commission errors, indicating deficits with sustained attention as well as impulse control and disinhibition (P < 0.001).

Language

Deficits in patients versus controls were identified on phonemic and semantic fluency tests (D-KEFS test; both P < 0.001). Phonemic fluency was more impaired than semantic (P < 0.001); controls provided an average of 4.3 more correct phonemic fluency answers than patients. Cerebellar patients were also impaired on pseudo-word decoding [Wechsler Individual Achievement Test; second edition (WIAT-II); P < 0.001] and the verb for noun generation task (Fiez, 1996; P < 0.001).

Visual-spatial function

Judgement of line orientation (JLO; Benton et al., 1983) was impaired (P = 0.001), as was the draw a clock test (P = 0.002) (Freedman et al., 1994) and copy a cube task (P < 0.001) (Kokmen et al., 1987). No significant differences were found between patients and controls on the MMSE copy a pentagon task (Folstein et al., 1975), or the Luria diagram copy (Luria, 1966).

Abstract reasoning

Cognitive estimation tasks were intact (e.g. ‘How tall is the empire state building?’; Macpherson et al., 2014), but patients were impaired on the similarities task of WAIS-IV (Wechsler, 2008) (P < 0.001), and on verbal addition and subtraction tasks (both P < 0.001). Addition and subtraction both require working memory, which was impaired.

Behaviour and affect

Neuropsychiatric symptoms measured by a standard assessment of executive behavioural dysfunction (FRSBE) (Grace et al., 1999) revealed that patients scored higher than controls on apathy, executive dysfunction and disinhibition (all P < 0.001). Patient self-report was no different than family member ratings. Neuropsychiatric behaviours evaluated with the CNRS (Schmahmann et al., 2007) revealed that family members reported difficulties with emotional control (P < 0.001), autism spectrum symptoms (P < 0.001), psychosis spectrum symptoms (P < 0.001) and deficient social skills (P = 0.002). Patients were also impaired on a questionnaire of social skills and communication (SCDC; Skuse et al., 1997).

Verbal memory

Cerebellar patients were not impaired with respect to controls in their ability to learn five words on the MoCA episodic memory test (P = 0.13), but they showed deficits on delayed recall (P < 0.001) and required category cues or multiple choice to retrieve the majority of the words. No patient in the exploratory cohort failed to retrieve learned words from multiple choice. Verbal associative learning measured by verbal paired associates (VPA-I and VPA-II) was impaired: patients had difficulty learning word pairs (P < 0.001) and with delayed recall (VPA-II; P < 0.001), and their learning slope between the four repetitions of the word pairs was impaired (P < 0.001).

Complex versus isolated degeneration versus isolated injury

There were no significant differences in performance between patients with complex or isolated cerebellar pathology (isolated cerebellar disease, isolated cerebellar injury) with the exception of WAIS-IV similarities, where ANOVA F between complex cerebrocerebellar disease/isolated cerebellar disease/isolated cerebellar injury was significant (F = 4.513; P = 0.015). Independent samples t-test showed that patients with complex cerebrocerebellar disease had lower scores on similarities than isolated cerebellar and isolated injury disease patients.

Cognitive performance and cerebellar ataxia scores

We analysed whether cognitive performance correlated with motor disability in patients with cerebellar disease as measured by the BARS total score, 25-foot walk and 9HPT. There was no correlation between cognitive domains and BARS scores. Without Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, scattered low level correlations (r ≤ −0.2) reached significance between some cognitive tests and 9HPT performance and 25-foot walk (Supplementary Table 6). As expected, motor tests correlated with each other: BARS − Pegboard (dominant hand) (r = 0.817, P < 0.001, n = 46), BARS − 25-foot walk (r = 0.479, P = 0.001, n = 43), and 25-foot walk − Pegboard (dominant hand) (r = 0.391, P = 0.003, n = 56) (Cohen, 1997).

Development of the cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale

The results were analysed to delineate a brief set of cognitive tests sufficiently sensitive to detect the presence of CCAS and selective enough to differentiate between cerebellar patients and controls.

Excluding MMSE total score, MoCA total score and the motor tests, performance was analysed on 34 tests, a total of 70 measures (Table 2), e.g. go/no-go total score, go/no-go omission mistakes, and go/no-go commission mistakes. Eight measures failed to show significant differences between patients and controls and were excluded from further analysis. These were: pentagon, word immediate recall, repetition errors in verbal fluency task, word repetition, omission errors in the go/no-go test, CNRS autism overshoot, and CNRS attention undershoot and overshoot.

Of the remaining 62 measures, 13 were excluded because absolute value difference was not sufficient to permit derivation of a diagnostic cut-off, even though the difference between patient and control mean raw scores was significant. These were: star draw, clock draw, MoCA animal naming, ideational praxis (planning), vigilance (letter A test), production of derived words, cognitive estimation, letter number sequencing, months backwards, oral sentence production test, word stem completion, addition and subtraction.

The remaining 49 measures were ranked for difference in z-score means between patients and controls (Supplementary Table 7). When we applied the a priori hypothesis that the scale should capture the defining cognitive and affective domains of CCAS (Table 4), we selected the following measures with the highest position in the z-score ranking: verb for noun, semantic fluency, category fluency accuracy, category fluency set loss, DSB, longest DSB, DSF, longest DSF, Trails B minus Trails A, verbal recall, CNRS psychosis overshoot, CNRS autism undershoot, CNRS psychosis undershoot, CNRS emotion undershoot, go/no-go, subtraction and cube.

Table 4.

Test measures

| Domain and test | Z-score difference between patients and controls | One-tailed paired t-test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | P | ||

| Executive function | ||||

| Trails B (s) | 7.30 | −6.535 | 62 | 0.000 |

| Go/No-go (commission mistakes) (TM) | 3.26 | 6.55 | 51 | 0.000 |

| Trails A (s) | 3.17 | −8.133 | 62 | 0.000 |

| Go/No-go (TS/2) | 1.44 | −6.381 | 63 | 0.000 |

| Category switching accuracy (TC) | 1.27 | −7.235 | 49 | 0.000 |

| Letter number sequencing time (s) | 0.88 | 3.702 | 45 | 0.001 |

| Trails B − Trails A (s) | 0.81 | −2.156 | 76 | 0.017 |

| Total D-KEFS set loss mistakes (TM) | 0.40 | −3.675 | 49 | 0.001 |

| Category switching set loss mistakes (TM) | 0.28 | 1.692 | 56 | 0.048 |

| Working memory | ||||

| DSB (TS/16) | 1.37 | −9.408 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Longest DSB (TS/8) | 1.05 | −8.541 | 61 | 0.000 |

| Longest DSF (TS/9) | 0.79 | −5.7 | 62 | 0.000 |

| Months backwards time (s) | 0.61 | 2.515 | 46 | 0.008 |

| DSF (TS/16) | 0.55 | −4.698 | 60 | 0.000 |

| Verbal memory | ||||

| Word delayed recall (TS/15) | 1.14 | −3.987 | 68 | 0.000 |

| Verbal paired associates-I (TS/32) | 0.70 | −4.354 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Learning slope | 0.70 | −4.304 | 59 | 0.000 |

| Verbal paired associates-II (TS/8) | 0.68 | −4.683 | 58 | 0.000 |

| Language | ||||

| Verb for Noun (TS/17) | 6.44 | −8.342 | 49 | 0.000 |

| Word Stem Completion (TS/22) | 1.95 | −4.272 | 48 | 0.000 |

| Phonemic fluency (TC) | 1.78 | −8.434 | 49 | 0.000 |

| Semantic fluency (TC) | 1.72 | −8.335 | 49 | 0.000 |

| Pseudoword Decoding at 60 s (TS/52) | 1.11 | −4.153 | 45 | 0.000 |

| Pseudoword Decoding at 30 s (TS/52) | 1.00 | −6.015 | 41 | 0.000 |

| Visual-spatial ability | ||||

| Cube (TS/2) | 0.81 | −4.442 | 61 | 0.000 |

| JLO (TS/15) | 0.44 | −3.233 | 58 | 0.001 |

| Attention and vigilance | ||||

| Longest DSF (TS/9) | 0.79 | −5.7 | 62 | 0.000 |

| DSF (TS/16) | 0.55 | −4.698 | 60 | 0.000 |

| Abstract reasoning | ||||

| Similarities (TS/36) | 1.11 | −7.032 | 58 | 0.000 |

| Affect | ||||

| CNRS Psychosis spectrum positive (TS) | 2.30 | 3.6 | 38 | 0.001 |

| CNRS Emotion regulation negative (TS) | 1.88 | 5.327 | 39 | 0.000 |

| CNRS Psychosis spectrum negative (TS) | 1.55 | 4.328 | 38 | 0.000 |

| FRSBE Total score (self rating) (TS/255) | 1.44 | 9.908 | 54 | 0.000 |

| FRSBE Dysexecutive (self rating) (TS/85) | 1.43 | 8.823 | 54 | 0.000 |

| FRSBE Apathy (self rating) (TS/85) | 1.42 | 7.985 | 54 | 0.000 |

| CNRS Emotion regulation positive (TS) | 1.38 | 3.982 | 39 | 0.000 |

| CNRS Autism spectrum negative (TS) | 1.31 | 4.713 | 38 | 0.000 |

| CNRS Social skill positive (TS) | 1.29 | 3.842 | 38 | 0.000 |

| FRSBE Apathy (family rating) (TS/85) | 1.28 | 6.731 | 38 | 0.000 |

| FRSBE Total score (family rating) (TS/255) | 1.07 | 5.465 | 38 | 0.000 |

| SCDC Total (TS/24) | 0.91 | 4.086 | 39 | 0.000 |

| CNRS Social skill negative (TS) | 0.86 | 3.138 | 38 | 0.002 |

| Dysexecutive (family rating) (TS/85) | 0.78 | 4.18 | 38 | 0.000 |

| FRSBE Disinhibition (self rating) (TS/85) | 0.61 | 3.567 | 54 | 0.001 |

| FRSBE Disinhibition (family rating) (TS/85) | 0.45 | 2.442 | 38 | 0.010 |

Test measures are ranked by descending order for difference in z-score means between patients and controls within each of the major CCAS domains (a priori requirement that the CCAS scale tests each domain).

TC = total correct; TM = total number of mistakes; TS = total score.

Some of these were inappropriately lengthy for a short bedside test and were excluded from the CCAS scale. In the verb for noun test, errors were distributed across the entire set of 22 noun-verb pairs, but no single noun or cluster of nouns elicited errors more predictably than others. The entire test would have had to be administered, a time-consuming challenge for the bedside/office setting. Similar reasoning applied to the Trails A and B tests. The timed tasks of months backwards and letter-number sequencing were also excluded because of the potential impact of motor impairment on test performance.

The measures of DSB total score, DSF total score and category fluency set loss were excluded because they provided no additional information to the measures of longest DSB, longest DSF and category fluency accuracy. Phonemic fluency placed high in the ranking of z-scores (Table 4) and was included (supported by Molinari et al., 1997; Leggio et al., 2000; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009b). The similarities test of abstract reasoning was added after reducing the original task from 18 associated word pairs to four word pairs. These were selected based on maximizing selectivity—most patients failed these items whereas controls passed them. In the scale, we chose different words within similar semantic categories to avoid copyright infringement (WAIS-IV; Pearson).

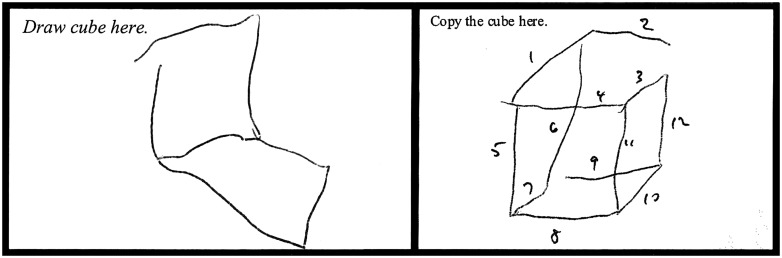

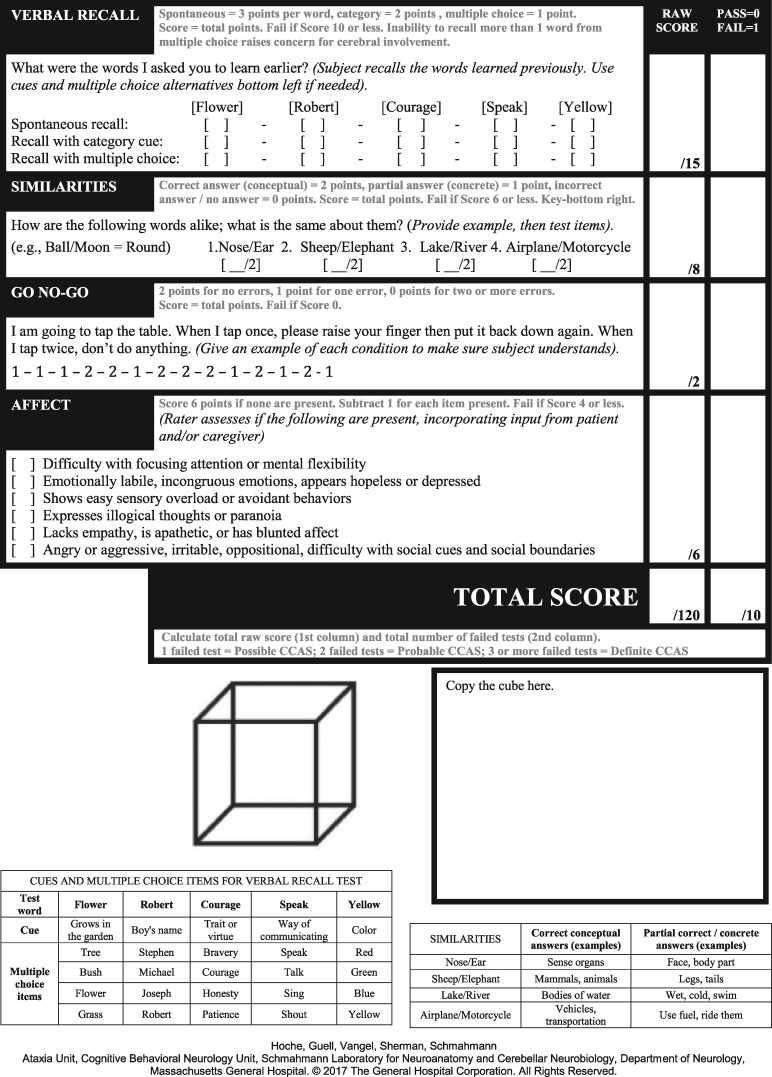

We amended the cube-copy task by adding the requirement that the subject first draw the cube from detailed verbal instruction. As we demonstrated in a study of metalinguistics abilities, cerebellar patients have difficulty self-directing their use of syntax in a context-dependent manner with only minimal constraints (Guell et al., 2015). On this basis, and consistent with the dysmetria of thought hypothesis (Schmahmann, 1991, 2010), we reasoned that cerebellar patients may similarly have more difficulty self-directing their own drawing of a cube in response to verbal instruction than they would when copying a cube that is a more constrained and visually-guided task. In the validation cohort of 39 patients, cube draw in this verbal instruction condition was impaired in 19 (49%); of these, five were able to copy the cube correctly (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Patient performance with verbal instruction to draw a cube (left) and to copy a cube (right).

The original description of CCAS included observations by the examiner, or report by caregivers, of changes in comportment, mood, affect and social behaviour as well as performances on bedside and neuropsychological tests. In the present analysis, CNRS measures were among the most sensitive discriminators between patients and controls. To meet the a priori requirement that the CCAS scale reflect the core aspects of the syndrome, we added a component that addresses cerebellar neuropsychiatry. Unlike the objective scoring criteria for the other tests in the scale, the resulting item is a clinical judgement by the examiner that takes into consideration the observations by the caregiver. This adds a clinically meaningful, albeit qualitative, screening assessment of the neurobehavioural/affective aspects of CCAS.

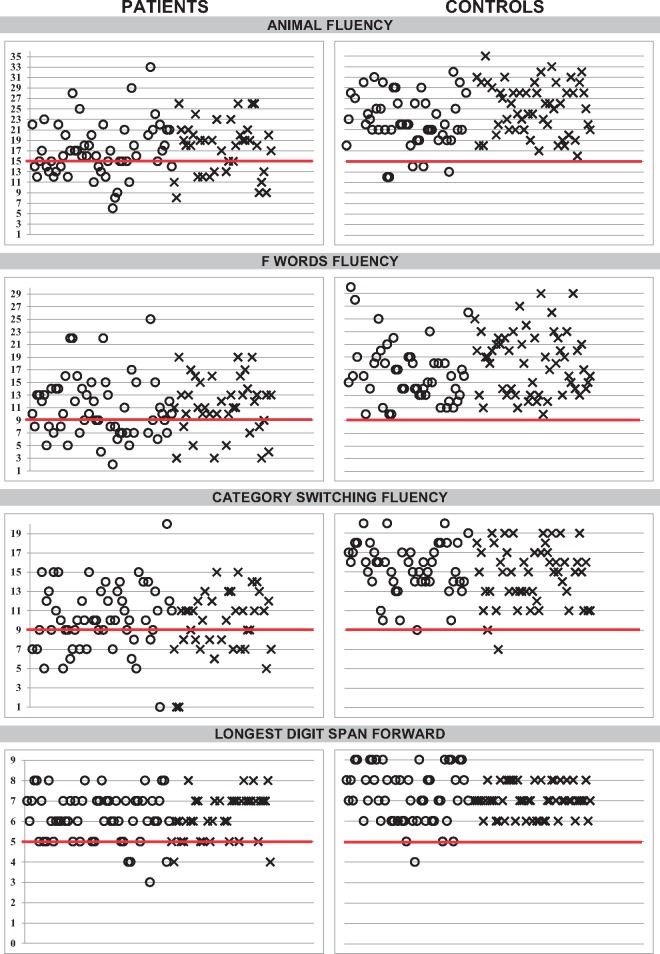

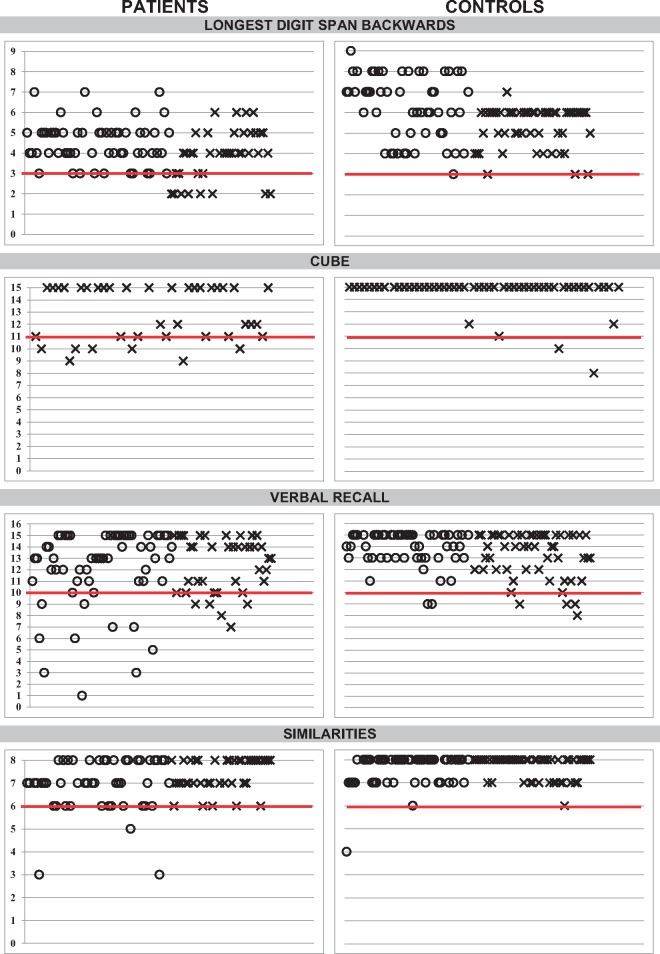

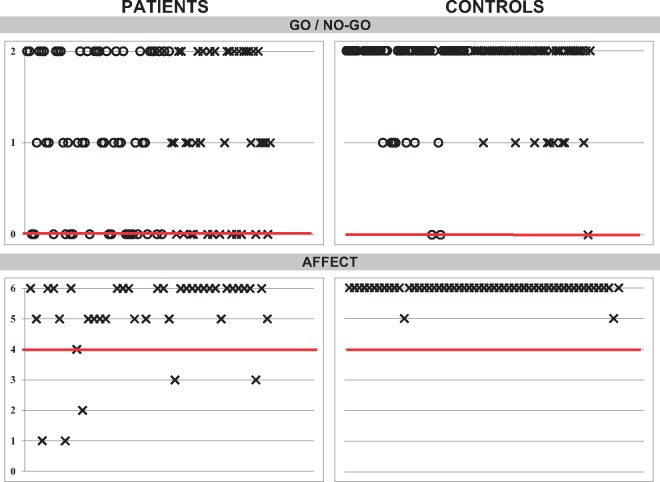

For each test item within the scale, there was a threshold score for the performance that distinguished patients from controls. This score was the diagnostic cut-off, used to determine pass/fail for each item. Diagnostic cut-offs were derived from the exploratory cohort and validated in the validation cohort. As exemplified by semantic fluency (Fig. 1), few controls scored ≤15 animals in 1 min (five in the exploratory cohort, 0 in the validation cohort), whereas 35 patients provided ≤15 animals (24 in the exploratory cohort, 11 in the validation cohort). We focused on selectivity (to prevent diagnosing a control person as a patient) rather than sensitivity (identifying all the patients), to prevent false positives. This is reflected in the designation of ‘possible’, ‘probable’, and ‘definite’ CCAS in which the selectivity goes up but the sensitivity goes down as the diagnosis becomes more firmly established (Table 5). Patients scored a mean of 6.25 on the DSF span length, but we chose 5 as a passing number/cut-off (as in MoCA) because a cut-off of 6 produced a higher false positive rate in controls who scored an average of 7.29. Threshold determined for success on the DSB span length is four digits, one digit more than on the MoCA. Patients scored a mean of 4.25 digits whereas controls provided an average of 6.25 digits backwards (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Scatterplots of performance of patients and controls on cognitive tests in the CCAS/Schmahmann scale. Bold line indicates the threshold value (the cut-off) determining that performance is impaired. Circles = exploratory cohort, crosses = validation cohort. Y-axis represents total raw scores.

Table 5.

Performance on subtests of the CCAS/Schmahmann scale by patients and controls in the exploratory and validation cohorts; and sensitivity and selectivity of the scale according to possible, probable and definite criteria

| Test | Cut-off (raw score) | Patients diagnosed as patients; exploratory cohort (%) | Patients diagnosed as patients; validation cohort (%) | Controls diagnosed as controls; exploratory cohort (%) | Controls diagnosed as controls; validation cohort (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal fluency | ≤15 | 24/56 (43) | 13/39 (33) | 45/50 (90) | 55/55 (100) |

| F word fluency | ≤9 | 25/56 (45) | 10/39 (26) | 50/50 (100) | 55/55 (100) |

| Category switching | ≤9 | 23/55 (42) | 18/39 (46) | 49/50 (98) | 53/55 (96) |

| LDSF | ≤5 | 15/58 (26) | 11/39 (28) | 49/53 (92) | 55/55 (100) |

| LDSB | ≤3 | 10/57 (18) | 12/39 (31) | 52/53 (98) | 52/55 (93) |

| Cube | ≤11 | 8/56 (14) | 14/39 (36) | 53/53 (100) | 51/54 (94) |

| Verbal recall | ≤10 | 12/56 (21) | 10/39 (26) | 51/53 (96) | 47/53 (89) |

| Similarities | ≤6 | 14/50 (28) | 5/39 (13) | 49/51 (96) | 54/55 (98) |

| Go/no-go | =0 | 17/56 (30) | 12/39 (31) | 51/53 (96) | 54/55 (98) |

| CCAS/Schmahmann scale | Sensitivity (%) | Selectivity (%) | |||

| Exploratory cohort | Validation cohort | Exploratory cohort | Validation cohort | ||

| One test fail (Possible CCAS) | 85 | 95 | 74 | 78 | |

| Two tests fail (Probable CCAS) | 58 | 82 | 94 | 93 | |

| Three tests fail (Definite CCAS) | 48 | 46 | 100 | 100 | |

LDSB = longest DSB; LDSF = longest DSF.

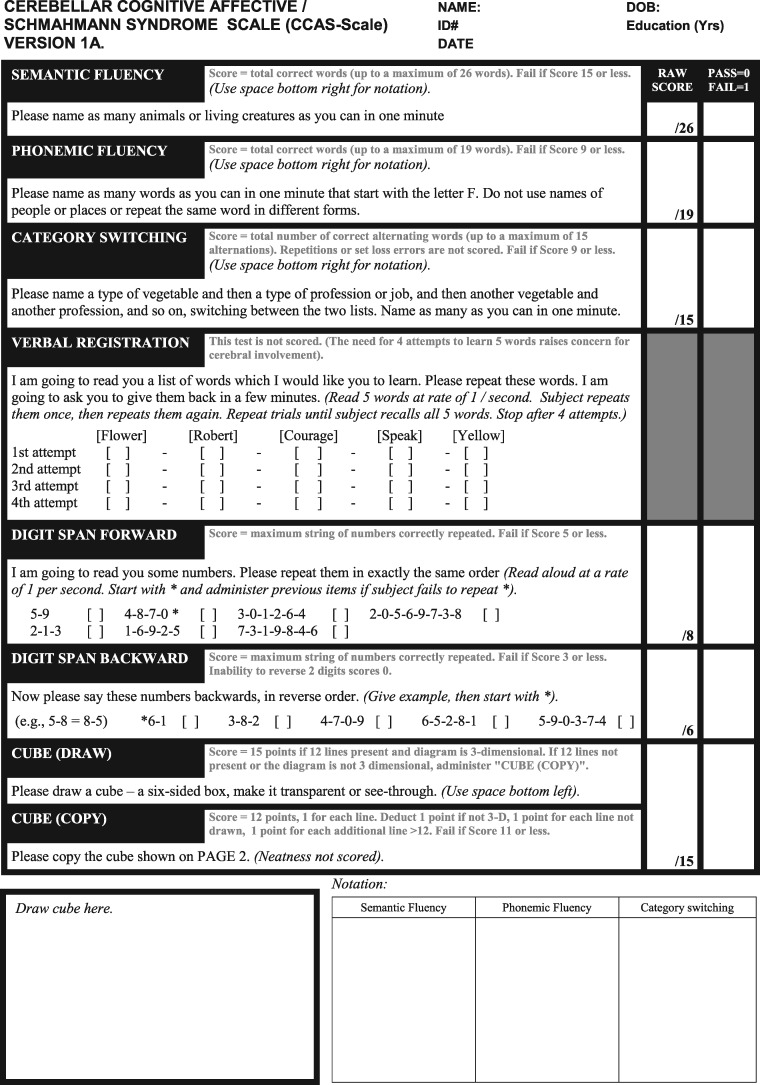

This resulting 10-item battery is the cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale, shown in Fig. 2. It measures semantic fluency, phonemic fluency, category switching, DSF, DSB, cube draw and cube copy, delayed verbal recall, similarities, go/no-go, and assessment of neuropsychiatric domains. It takes <10 min to administer to a healthy control, and 12–15 min for a patient with cerebellar dysfunction.

Figure 2.

The cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale (Version 1A). See Supplementary material for administration and scoring instructions, and Versions 1B, 1C, and 1D that have different test items within each domain to facilitate test-rest reliability.

Each test within the scale has a threshold score allowing a pass/fail determination that differentiates cerebellar patients from controls. Table 5 shows the performance of patients and controls determined by cut-offs for the nine cognitive test items on the CCAS scale (excluding the Affect component).

We reasoned that total raw score for the scale (the sum of the raw scores of all the subtests) would increase granularity in scoring and allow for more nuanced detection of changes over time in individual patients. To do this we needed an upper limit of the raw score for some measures because they would potentially have undue weight on the total score. We set the maximum possible score as 1 SD above the mean for the performance of controls on tests of semantic fluency, phonemic fluency, category switching, and longest digit span forwards. For the other tests, the maximum score is a perfect score for that test (cube, verbal recall, similarities, go/no-go). The Affect denominator was kept low to avoid skewing results with subjective data. Neuropsychiatric features within CCAS may be assessed more directly and in greater detail by the CNRS.

With these criteria, a diagnosis of CCAS in the large exploratory cohort based on a single failed test yields a sensitivity of 85% but selectivity of 74%—an unacceptably high false positive rate of 26%. Diagnosis of CCAS based on two failed tests yields a sensitivity of 58.3% and selectivity rate 94.4%. Failure on three tests translates to a sensitivity of 48.3% and selectivity 100%, i.e. no control subject failed three tests. We therefore chose to consider one failed test as a diagnosis of possible CCAS, two failed tests as probable CCAS, and three failed tests as definite CCAS (Table 5).

Validation of the cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale

The scale was administered in a prospective manner to a validation cohort of 39 new patients with cerebellar disorders who were not part of the original exploratory cohort (Table 3). Of these, 23 were isolated cerebellar disorders (acquired or hereditary), and 16 were complex cerebrocerebellar disorders. These were compared with 55 healthy controls. The control cohort (40.43 ± 16.24 years) was younger than the patients (55.01 ± 12.48 years; two-tailed P-value < 0.001). In the controls, there were no significant correlations between age and test scores with the single exception of verbal recall (Pearson’s r = −0.438, one tailed P-value < 0.001). There was no difference in educational level between patients 15.64 ± 2.07 years and controls 16.28 ± 1.16 years; two-tailed P-value = 0.08).

The sensitivity and selectivity of the CCAS scale in the validation cohort of cerebellar patients and healthy controls was comparable or slightly improved compared to the results in the exploratory cohort. A diagnosis of possible CCAS (one test failed) achieved 95% sensitivity and 78% selectivity, probable CCAS (two tests failed) 82% sensitivity and 93% selectivity, and definite CCAS (three or more tests failed) achieved 46% sensitivity and 100% selectivity.

Cronbach’s alpha for the CCAS scale administered to the validation cohort was 0.59, reflecting only modest internal consistency. This means that patient performance on any single item in the scale did not predict performance on other items within the scale, and therefore the items within the scale are necessary, and not redundant.

As in the exploratory cohort, the patient validation cohort was quite heterogeneous in terms of diagnosis; 22 of 39 patients had diagnoses shared by others (Table 3). Further, the distribution of failing scores across the scale was random, with no consistent pattern identifiable. Only three pairs of patients failed the same two tests, and each had a different diagnosis. We used logistic regression to assess whether disease duration is associated with a pattern of test failure, and found a significant association only for phonemic fluency (P = 0.02). Logistic regression applied to the performance across the 10 tests on the scale showed no association (P > 0.09) between the number of failures for any single test and isolated cerebellar (n = 23) versus complex cerebrocerebellar (n = 16) condition. Total BARS score correlated with phonemic fluency (Pearson’s r = −0.45, two tailed P < 0.01) and with affect (r = 0.57, P < 0.001).

Discussion

This study reaffirms that executive, linguistic, visual spatial and affective/neuropsychiatric impairments characterize the disturbances of higher function in patients with cerebellar injury—CCAS/Schmahmann’s syndrome (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1997, 1998; Levisohn et al., 2000; Schmahmann et al., 2007; Manto and Mariën, 2015).

Executive function

As originally described, executive function impairments in patients with focal cerebellar injury included deficient planning, abstract reasoning, and working memory, with impaired motor or ideational set-shifting, perseveration of actions or drawings, and decreased verbal fluency sometimes with telegraphic speech so severe as to resemble mutism (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998). Following cerebellar tumour resection children demonstrated deficits in planning and sequencing, impaired digit span, perseveration, and difficulties establishing set (Levisohn et al., 2000).

In the present study, prominent deficits were noted on DSF, DSB, Trails B, and D-KEFS category switching. Deficits were also found for commission mistakes on the go/no-go task, and letter number sequencing total score and vigilance (Table 2). These cognitive tests tap executive functions including working memory, mental flexibility, problem-solving strategies, multitasking, planning, sequencing, and self-organizing. Impairments on these tests are associated with clinical deficits including concrete thinking and perseveration (Botez et al., 1989; Schmahmann and Sherman, 1997, 1998; Levisohn et al., 2000; Ravizza et al., 2006; Leggio et al., 2011; reviewed in Koziol et al., 2014). Working memory deficits that have been widely reported in cerebellar patients (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998; Justus et al., 2005; Ravizza et al., 2006) depend on a network of frontal and parietal cortical regions as well as subcortical structures (Rowe et al., 2000). It has been proposed that cerebellar patients are impaired on working memory tasks because of deficient silent rehearsal of verbal information (Desmond et al., 1997; Chen and Desmond, 2005; Mariën et al., 2014). Diminished attentional resources may also contribute to working memory impairments (Purcell et al., 1998; Klingberg et al., 2002; Egeland et al., 2003).

Linguistic function

The language deficits in the original report (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998) included dysprosodia, agrammatism, anomia and impaired syntax, in addition to the deficits in verbal fluency, telegraphic speech, and mutism. Language impairments in children following cerebellar tumour resection were characterized by expressive language deficits, word-finding difficulties evident in spontaneous conversation and testing, and mutism in those with damage to the vermis (Levisohn et al., 2000). Subsequent insights into the modulatory role of the cerebellum in language include the contribution of the cerebellum to speech and language perception, motor speech planning, syntax processing, and the dynamics of language production, reading and writing (Mariën et al., 2014). Phonological and semantic verbal fluency tasks and verbal working memory tests also tap executive function, but these tests rely heavily on verbal output and therefore reflect the integrity of language processing as well.

Here we demonstrate deficits in oral word production (verb for noun task) (Fiez, 1996; Stoodley et al., 2012), syntax processing (production of derived words), oral sentence production (Justus, 2004; Michael and Kenneth, 2015), and phonological processing (pseudoword decoding task) (Stoodley, 2015). Phonemic (letter) and semantic fluency (category naming) were also impaired, phonemic more than semantic, as noted previously (Silveri et al., 1994; Molinari et al., 1997; Schmahmann and Sherman, 1997, 1998; Leggio et al., 2000; Levisohn et al., 2000; Mariën et al., 2001, 2014; Gottwald et al., 2003; Brandt et al., 2004; Richter et al., 2007; Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009b; Peterburs et al., 2010; Schweizer et al., 2010; Tedesco et al., 2011; Arasanz et al., 2012; Mariën and Beaton, 2014). Cerebellar patients could name the three animals on the MoCA semantic memory/knowledge task, but in comparison to controls they were impaired on the D-KEFS category fluency task in which they needed to generate animals and boys’ names. Deficits on the semantic fluency task likely reflect dysfunctional executive retrieval of semantic knowledge subserved by prefrontal cerebrocerebellar circuits rather than a primary storage defect associated with medial temporal lobe pathology. Thus, naming tasks may distinguish patients with pathology of the temporal lobe in whom animal naming may be impaired, from patients with disruption of prefrontal cortices or associated cerebrocerebellar circuitry in whom the pictured animal naming task, with its minimal executive retrieval demand, is intact.

Metalinguistic deficits are noted in cerebellar patients, manifesting as impaired understanding of metaphor, ambiguity, and inference, and generation of grammatically and syntactically correct sentences according to context (Guell et al., 2015), but we did not evaluate this task in the present cohort.

Visual spatial function

Deficits in spatial cognition in the original study were demonstrated when patients attempted to draw or copy a diagram. The approach to the drawing was not sequentially ordered, and the conceptualization of the figures was disorganized. Some patients demonstrated simultanagnosia (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998). Children post-tumour resection also showed deficits in visual-spatial functions, including marked fragmentation of a complex figure copy (Levisohn et al., 2000), a phenomenon observed subsequently in children with ataxia telangiectasia (Hoche et al., 2014, 2016a).

In the present study patients were impaired on JLO (Benton et al., 1983), draw a clock (Freedman et al., 1994), and the copy a cube task (Kokmen et al., 1987). In contrast, no difference between patients and controls was found on the ability to copy intersecting pentagons (in the MMSE) and a triangle. The distinction between intact performance on the 2D tasks versus impaired 3D copy and JLO may be explained by damage to the cerebellar posterior lobe, which is linked with cerebral posterior parietal association cortices (Schmahmann and Pandya, 1989) concerned with internal representations of spatial maps, and with the dorsal premotor cortices (Middleton and Strick, 1994; Schmahmann and Pandya, 1995, 1997) concerned with motor imagery (Guillot and Collet, 2010). Both these cerebral cortical areas are involved in spatial transformation and mental rotation tasks (Gerardin et al., 2000; Cengiz and Boran, 2016).

Memory and learning

Cerebellar-based memory impairments defined in the 1998 study included working memory, and efficiency of retrieval of previously learned information. This pointed to a cerebellar role in the executive control of memory. Later imaging studies suggested this was related to the cerebellar contribution to search functions, rather than storage of information (Desmond et al., 1997; Marvel and Desmond, 2010). These findings are consistent with anatomical studies in monkey of prefrontal cerebrocerebellar connections (Schmahmann and Pandya, 1995, 1997; Kelly and Strick, 2003) and resting state functional connectivity using MRI in humans showing representation in the cerebellum of the frontoparietal and default mode networks (Habas et al., 2009; O’Reilly et al., 2010; Buckner et al., 2011).

Here we show that episodic memory impairments in cerebellar patients are similar to those in patients with prefrontal dysfunction, namely, deficits in retrieval and associative learning (Preston and Eichenbaum, 2013). A standard test of verbal associative learning (VPA-I and VPA-II) revealed deficits on immediate and delayed recall of associated word pairs. The learning slope between the four repetitions of the associated word pairs was also impaired. This is consistent with the observation that the cerebellum participates in the acquisition of cognitive associations and associative learning (Gerwig et al., 2007; Sacchetti et al., 2009; Thompson and Steinmetz, 2009; Timmann et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2014). Whether the discrepancy between relatively preserved five-word recall and the impaired associative learning reflects deficient encoding or impaired retrieval of the fully encoded verbal pairs remains to be determined.

Our clinical experience with patients in the late stages of disease known to involve cerebral hemispheres as well as cerebellum e.g. SCA2 (Koeppen, 2002; Seidel et al., 2012), Gordon Holmes syndrome (Seminara et al., 2002; Margolin et al., 2013; Santens et al., 2015), and fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome (Hagerman et al., 2001; Santens et al., 2015) is that they develop episodic memory loss that is not seen in CCAS. This conclusion is supported by our finding that patients with these diagnoses in the validation cohort (SCA2, FAXTAS, Gordon Holmes syndrome) failed the memory test in the scale; these were the only patients of the 116 in both the exploratory and validation cohorts who were unable to recall words from a multiple-choice list (data not shown). Thus, whereas the executive aspects of memory (speed and accuracy of retrieval) appear to be under the influence of the cerebellum, storage of declarative memories appears to escape cerebellar influence. From this perspective, in a patient with cerebellar disease, memory loss (inability to recall words from multiple choice) should be regarded as a red flag pointing to a non-cerebellar basis of the memory impairment.

Neuropsychiatry of the cerebellum

The present findings are harmonious with our previous report that cerebellar patients experience deficits in attentional control, emotional control, autism spectrum symptoms, psychosis spectrum symptoms, and deficient social skills (Schmahmann et al., 2007). These results are also in line with scores on the CNRS in a study of social cognition in cerebellar patients showing impairments on assessments of emotion control, autism spectrum behaviours, psychosis spectrum symptoms and social skills (Hoche et al., 2016b). Further, they are consistent with the observations from the FRSBE, a standard assessment of executive behavioural dysfunction (Grace et al., 1999), in which family members and patients reported apathy and disinhibition.

Cerebellar versus cerebrocerebellar contribution to cognitive function

Group-wise analysis revealed no differences in performance of patients with isolated cerebellar disease, injury, or complex cerebrocerebellar disease pathology on any of the neuropsychological tests administered, with the exception of similarities. This indicates that cerebellar disease alone is sufficient to produce CCAS. This interesting result speaks to the role of cerebellum in executive, visual spatial, linguistic and affective behaviours that characterize CCAS. It remains to be determined how cerebral hemisphere involvement in addition to cerebellar dysfunction affects these cognitive and neuropsychiatric domains. The CCAS scale will be helpful in that regard, supplemented by the additional tests defined here that when administered in the neuropsychology laboratory can detect CCAS. We draw attention again to the observation that impairment of declarative memory, with difficulty recalling words even from multiple choice, is a ‘red flag’ for cerebral hemisphere involvement because this is not part of the core constellation of CCAS. The heterogeneity and large number of patients in this study (n = 116, 77 exploratory and 39 validation) serves as the basis for these conclusions, and it will be important to explore this further with larger groups of patients and a wide range of cerebellar and cerebrocerebellar disorders.

MMSE and MoCA

Despite the facts that cerebellar patients failed many standard neuropsychological and experimental tests, and were significantly different than control subjects on MoCA total score, they performed within the published normal ranges on both the MMSE and the MoCA. This may be explained by the fact that MMSE and MoCA contain many test items that are insensitive to those cognitive functions that are compromised in cerebellar patients. This also masks the finding that the MoCA subtests with which patients struggled tap the same domains that were impaired on neuropsychological tests in the exploratory cohort, and on the CCAS scale in the validation cohort. The MoCA domains that were impaired included trail making, clock draw, visual spatial domain, reverse digit span, subtraction, phonemic fluency, language, abstract reasoning, and delayed recall. These deficits on MoCA subtests are lost in the summation of the total score. MoCA was therefore inadequate to detect CCAS in cerebellar patients for three reasons: (i) the individual MoCA cut-offs are too lenient (e.g. digit span backwards); (ii) some tests are mini versions of the original test design (e.g. Trails) and are not sufficiently sensitive in this population for the mental flexibility that this test assesses; and (iii) errors in critical cognitive skills are hidden in the total MoCA score, overwhelmed by preserved performance on tasks spared in patients whose lesions are confined to the cerebellum.

Cognitive performance does not correlate with motor deficit

The tests that rate the severity of motor ataxia correlated with each other. Correlations were strong between BARS and the 9HPT, while the 25-foot timed walk had modest correlations with BARS and with the 9HPT.

In contrast, in the exploratory cohort none of the CCAS domains correlated with total BARS score. A small number of items of the CCAS scale had low level correlations with 25-foot timed walk and 9HPT performance. In the validation cohort, total BARS score correlated only with phonemic fluency (a shorter version of the test than was administered to the exploratory cohort), and with affect, which was not measured in the same way in the exploratory cohort. This motor-cognitive relationship, or lack thereof, will need to be explored in future studies using the new scale in larger cohorts, but it underscores the motor-cognitive dichotomy in cerebellum, in which the sensorimotor cerebellum is represented in the anterior lobe and lobule VIII, and the cognitive cerebellum in the massively expanded posterior lobe (lobules VI, VII and probably lobule IX). Some correlations are to be expected, given the different patterns of pathology in many of our cases, and this likely reflects involvement by the disease process of cerebellar areas engaged in these motor or cognitive/emotional behaviours. The existence of functional topography of different domains of cognition within the cerebellum (e.g. Stoodley and Schmahmann, 2009a, b; Schmahmann, 2010) is directly relevant to the development of the CCAS/Schmahmann scale. The internal consistency of the scale as measured by Cronbach alpha is modest, indicating that no single test, or aggregation of tests, can fully predict performance on the scale as a whole. This reflects the observation that different parts of the cerebellum are engaged in different cognitive and affective processes. It is not mandatory that all features of CCAS (executive, linguistic, visual spatial, affective), manifest in every patient with damage localized to the cognitive/limbic cerebellum. This is determined, in large part, by the precise location of the lesion, a well-established principle in neurology in general, and behavioural neurology/neuropsychiatry in particular.

Development of the CCAS/Schmahmann scale

We derived a subset of tests sensitive to the presence of CCAS in cerebellar patients that distinguished between cerebellar patients and healthy controls, and which is brief enough to be useful in the clinic or bedside setting. When ranking all tests administered to the exploratory cohort for their difference in performance between patients and controls, the results were weighted towards executive and language functions, consistent with the original observations that executive function impairment was a prominent feature of CCAS, followed by language, visual spatial and affective changes (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998). Similarly, we confirm previous reports (Schmahmann and Sherman, 1998; Schmahmann et al., 2007; Garrard et al., 2008; Sokolovsky et al., 2010; Hoche et al., 2016b) that adults with cerebellar lesions show emotional dysregulation, difficulties with social skills and psychosis spectrum behaviours, but not autism spectrum behaviours that are more evident in children.

In developing the CCAS scale we did not include some tests that reached significance in the exploratory cohort. The omission of these tests did not alter the sensitivity or selectivity of the resulting scale, as confirmed in Table 2 and Supplementary Table 7. The brief tests included in the scale all had high sensitivity and selectivity, and were essentially interchangeable with the longer tests that were not practical for the screening instrument.

To screen for the CCAS pattern in each individual patient with cerebellar injury in a bedside setting, the scale was developed using the a priori hypothesis that all characteristics of CCAS should be represented. We eliminated some tests either because they take too long to administer in an office or bed-side encounter (e.g. the full Trails test, or all the words of the verb-for-noun task), or because the absolute value difference between patients and controls was too small to be useful in that setting.

The resulting cerebellar cognitive affective/Schmahmann syndrome scale (Fig. 1) has three defining components:

A pass/fail diagnostic cut-off score for each test within the scale. To our knowledge this feature is unique, and the first time this approach has been introduced into any screening cognitive instrument.

A pass/fail for the scale as a whole, which determines the likelihood that the subject has CCAS or not, and provides evidence supporting the stratification into possible, probable, or definite CCAS.

The scale total raw score facilitates a more granular analysis of patient performance. Note that the range of passing scores on the scale extends from 82 (sum of minimum passing scores for each item on the scale) to 120 (sum of maximum scores for each item as described above). A patient can have definite CCAS (three failed test items) with a total raw score that falls in the 82–120 range. The total score does not determine whether a patient has CCAS or not, but it does provide additional quantitative detail of a patient’s performance in each domain that can be used for longitudinal follow-up. Thus, for example, a subject may fail the semantic fluency task by producing 15 words or less, but this could decline further, reflecting deterioration. Alternatively, a subject could fail this task by producing only a few words (e.g. five or six), but improve over time as they recover, but still failing the task by not reaching the required 15 words. One could also pass the test with 25 words, and then decline over time to 16 words, but still pass that aspect of the test—this fine-tuning of the scale with the raw score is a potentially powerful tool for the clinician following a patient over time.

The patient populations in both the exploratory and validations cohorts were remarkably heterogeneous, underscoring the suitability of the new scale for a general population of cerebellar patients. The scale has the potential to be a powerful screening and evaluation instrument to determine the presence of CCAS in an individual patient accurately, efficiently and in a validated manner, allowing for monitoring over time of cognitive changes, emergence of novel deficits in previously unaffected domains, and improvement reflecting recovery from injury or improvement with therapy.

Administration and Scoring Instructions for the scale can be found in the Supplementary material.

Alternative versions of the scale

We developed new normative data on relevant test items for versions 1B, 1C, and 1D of the scale to avoid practice effects in subsequent administrations (Supplementary Table 9 and Supplementary material). Versions 1B, 1C and 1D have not been tested in other validation cohorts, but the approach taken to develop them was rigorous. All verbal fluency items used in the retest versions (semantic, phonemic, and category switching), and words used in the memory test and in the similarities test, were developed and refined in healthy controls. We used words within the same semantic categories, and we matched frequency of word usage according to published guidelines (Brysbaert and New, 2009). For phonemic fluency we selected alternative letters that have the same frequency of usage in the English language. Using a randomizer, we scrambled the numbers in the digit span forwards and backwards tasks, and the order of stimuli in the go/no-go task. Items not changed in the retest versions were Question 10 (neuropsychiatry), and the cube-draw condition, which requires that the diagram be explained to the subject verbally, before they are asked to copy the diagram if they are unable to provide an accurate drawing from their own concept of how a cube should look. These alternative retest versions of the scale (Versions 1B, 1C and 1D) will need to be evaluated in future prospective studies to determine if they are equivalent to the original version (1A), but the care with which these versions were developed predisposes them to a high degree of reproducibility.

Additional neuropsychological tests useful for detection of CCAS

There are eight tests that distinguished cerebellar patients from controls but which were not included in the CCAS scale. This set, derived from the 17 top-ranked tests minus the nine cognitive tests included in the scale, may be useful for exploration of CCAS when administered by trained personnel in neuropsychology laboratories. These are: Trails B in relation to Trails A, verbal paired associates I and II (VPA), verb for noun, pseudoword decoding, JLO, full similarities (WAIS-IV), FRSBE, and SCDC.

Limitations

The CCAS scale was derived from an adult cohort with known disease of the cerebellum. A paediatric version of the CCAS scale is in development but not yet finalized. Our exploratory cohort included mostly patients with degenerative disorders and a relatively small number of patients (nine) with focal cerebellar lesions. The validation cohort added nine more patients with focal cerebellar injury (haemorrhage, stroke, tumour), but these numbers are insufficient to perform definitive correlations between structure and cognitive function. Such analyses have recently been performed in cerebellar stroke patients (Stoodley et al., 2016), and further studies of this type are needed to provide deeper insights into cerebrocerebellar anatomical and cognitive networks. By providing new normative data for alternative items within each test item of the scale we facilitate repeat testing while avoiding practice effects. Future studies need to test scale Versions 1B, 1C and 1D in new healthy and disease validation cohorts. It remains to be shown in future studies whether the CCAS/Schmahmann scale, alone or in conjunction with the CNRS, can detect a cerebellar contribution to cognitive decline and neuropsychiatric manifestations in a broader set of neurology and psychiatry patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Casey Evans, Jessica A. Harding, Winthrop P. Harvey, Bruna Olson Bressane, and Ramya Rangamannar for assistance in collecting and entering data, Jason Macmore for assistance in collecting data and technical support throughout the study, and Marygrace Neal for clinical support for patients involved in the study.

Funding

Supported in part by NIMH RO1 MH67980, the National Ataxia Foundation, Ataxia Telangiectasia Childrens’ Project, and the MINDlink Foundation.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BARS

Brief Ataxia Rating Scale

- CCAS

cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome

- CNRS

Cerebellar Neuropsychiatric Rating Scale

- D-KEFS

Delis Kaplan Executive Function System

- DSB

Digit Span Backward

- DSF

Digit Span Forward

- FRSBE

Frontal System Behavior Scale

- JLO

Judgement of Line Orientation test

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- SCDC

Social and Communication Disorder Checklist

- WAIS-IV

Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–fourth edition

- WIAT-II

Wechsler Individual Achievement Test–second edition

References

- Adamaszek M, D'agata F, Ferrucci R, Habas C, Keulen S, Kirkby KC, et al. Consensus paper: cerebellum and emotion. Cerebellum 2017; 16: 552–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arasanz CP, Staines WR, Roy EA, Schweizer TA. The cerebellum and its role in word generation: a cTBS study. Cortex 2012; 48: 718–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher K, Varney NR, Spreen O. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment. New York: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Botez MI, Botez T, Elie R, Attig E. Role of the cerebellum in complex human behavior. Ital J Neurol Sci 1989; 10: 291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]