Abstract

Background: Policy makers are being encouraged to specifically target sugar intake in order to combat obesity. We examined the extent to which sugar, relative to other macronutrients, was associated with adiposity.

Methods: We used baseline data from UK Biobank to examine the associations between energy intake (total and individual macronutrients) and adiposity [body mass index (BMI), percentage body fat and waist circumference]. Linear regression models were conducted univariately and adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity and physical activity.

Results: Among 132 479 participants, 66.3% of men and 51.8% of women were overweight/obese. There was a weak correlation (r = 0.24) between energy from sugar and fat; 13% of those in the highest quintile for sugar were in the lowest for fat, and vice versa. Compared with normal BMI, obese participants had 11.5% higher total energy intake and 14.6%, 13.8%, 9.5% and 4.7% higher intake from fat, protein, starch and sugar, respectively. Hence, the proportion of energy derived from fat was higher (34.3% vs 33.4%, P < 0.001) but from sugar was lower (22.0% vs 23.4%, P < 0.001). BMI was more strongly associated with total energy [coefficient 2.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.36-2.55] and energy from fat (coefficient 1.96, 95% CI 1.91-2.06) than sugar (coefficient 0.48, 95% CI 0.41-0.55). The latter became negative after adjustment for total energy.

Conclusions: Fat is the largest contributor to overall energy. The proportion of energy from fat in the diet, but not sugar, is higher among overweight/obese individuals. Focusing public health messages on sugar may mislead on the need to reduce fat and overall energy consumption.

Keywords: adiposity, obesity, diet, sugar

Introduction

The global prevalence of overweight and obesity has nearly doubled over three decades,1 with recent health surveys reporting that more than half the adult population in Europe,2 and two-thirds in the USA,3 are now overweight or obese. Sugar consumption has been implicated as a major contributor to obesity. There is a correlation between the sugar consumption in a country and its prevalence of obesity.4 The past three decades of the 20th century saw rapid increases in both sugar consumption and obesity; however, obesity continued to increase beyond 2000 in spite of reported falls in sugar consumption.5 Sugar has little nutritional value beyond energy provision and is often referred to as ‘empty calories’. Furthermore, sugar-sweetened beverages provide energy but contribute little to satiety.6 Therefore, there has been increasing pressure on policy makers to adopt interventions targeted specifically at sugar intake,7 such as imposition of a ‘sugar-tax’.8,9

However, the association between sugar intake and obesity is due to the contribution of sugar to overall energy consumption, rather than a specific effect of sugar. All macronutrients, other than fibre, contribute to overall energy intake and researchers have suggested there may be a ‘sugar-fat seesaw’ whereby individuals who are free to choose their diets compensate for a change in the consumption of one by a reciprocal change in the other. Therefore, focusing on sugar in isolation may not be the best approach to reducing overall energy intake.5,10 The aim of this study was to explore the relationships between macronutrients, including sugar, and several adiposity measures in the general population.

Methods

UK Biobank is a very large, general population cohort study. Between 2007 and 2010, 502 682 participants, aged 40–69 years, were recruited and underwent baseline assessments at 22 centres across England, Scotland and Wales. Detailed information was obtained via a self-completed, touch-screen questionnaire and a face-to-face interview, and trained staff undertook a series of measurements using standard operating procedures. Following completion of the baseline assessment, participants were invited to complete an online dietary questionnaire on four occasions: February, June and October 2011 and April 2012. The duration of light, moderate and vigorous physical activity undertaken over the previous 24 h was self-reported using the Oxford WebQ.11 These were converted into metabolic equivalents (MET-h/week) by applying weights of 2.5, 4 and 8, respectively, and then summed to derive overall daily energy expenditure from physical activity. Ethnicity was self-reported and categorized into: White, South Asian, Black, Chinese, other and mixed. Smoking status was self-reported and classified as: never, former and current. Participants reported physician’s –diagnoses of previous and current medical conditions. Height was measured to the nearest centimetre (cm) using a Seca 202 height measure, and a Tanita BC-418 body composition analyser was used to measure weight to the nearest 0.1 kg and body fat to the nearest 1 g, by bio-impedance. The measurements were used to derive three measures of adiposity: body mass index (BMI), percentage body fat and waist circumference. BMI was derived from weight [kg) / (height (m) x height (m)] and categorized according to the World Health Organization definitions into: underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and obese (≥ 30.0 kg/m2). Obese was further categorized into: obese 1 (30.0–34.9 kg/m2), obese 2 (35.0–39.9 kg/m2) and obese 3 (≥ 40.0 kg/m2).

Dietary information was collected via the Oxford WebQ; a web-based 24-h recall questionnaire which was developed specifically for use in large population studies and has been validated against an interviewer-administered 24-h recall questionnaire.11 The Oxford WebQ derives energy intake (total and from specific macronutrients) from the information recorded in McCance and Widdowson’s The Compositionof Food, 5th edition.11 The macronutrients studied were: fat, sugar, starch, protein and fibre. For participants who completed more than one online dietary questionnaire, mean values were calculated from all of the information provided.

We defined as ineligible for inclusion those individuals: who might have unintentional weight loss (current smokers and history of myocardial infarction, heart failure, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis and rheumatoid arthritis); whose energy intake was suggestive of current dieting or under-reporting (overall energy intake < 1.1 x basal metabolic rate (BMR),12 with BMR calculated using the Oxford equations13); or those with implausible outlier values (BMI < 14.9 kg/m2 or > 60 kg/m2, waist circumference or percentage body fat more than four standard deviations from the mean values or overall energy intake > 18 828 KJ14).

We compared men and women in terms of anthropometric measurements, level of physical activity, total energy intake, absolute energy derived from each macronutrient, and percentage of total energy derived from each macronutrient. The same comparisons of energy intake were then applied to the BMI groups. The latter analyses were undertaken for men and women separately and combined. P-values were obtained using χ2 tests, and χ2 tests for trend, for categorical and ordinal data, respectively, and Kruskal–Wallis tests and t tests for non-parametric and parametric continuous data, respectively. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine the extent to which higher intake of one macronutrient was associated with higher intake of another. These were calculated for both absolute energy derived for each macronutrient and percentage contribution to total energy intake.

The adiposity measures (BMI, percentage body fat and waist circumference) were treated as continuous, dependent variables in a series of multivariable, linear regression models undertaken for men and women separately and then combined. Overall and sex-specific quintiles were derived for overall energy intake, and absolute energy was derived for each macronutrient and for the percentage of total energy derived from each macronutrient. The quintile representing the lowest level of consumption was treated as the referent category. The models were adjusted for age and ethnic group, as well as sex in the analyses of men and women combined, with subsequent additional adjustment for level of physical activity. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

This study was performed under generic ethical approval obtained by UK Biobank from the NHS National Research Ethics Service (approval letter ref 11/NW/0382, dated 17 June 2011).

Results

Of the 502 682 UK Biobank participants, 211 066 (42.0%) had completed at least one of the online 24-h dietary recall questionnaires. Of these, 78 587 were excluded: 37 514 were current smokers or had comorbid conditions commonly associated with unintentional weight loss; 39 673 had energy intake values < 1.1 x BMR, suggestive of weight reduction diets or under-reporting; 1007 reported implausibly high values for energy intake; and 393 had missing data that was required for the calculation of BMR. The remaining 132 479 participants comprised the study population (Supplementary Figure 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). They had a mean age of 56.1 years, 53 720 (40.5%) were male and 127 228 (96.0%) were White (Table 1). Men had a higher overall energy intake than women (mean 10 556 kJ/day vs 8793 kJ/day). Compared with men, women derived a lower percentage of their energy intake from starch (23.0% vs 23.9%, P < 0.001), and a higher percentage from all other macronutrients including sugar (23.7% vs 22.0%, P < 0.001). Fat provided the largest contribution to total energy intake in both men and women. The minimum and maximum values for quintiles of absolute energy intake, and percentage of total energy intake by macronutrient, are contained in Supplementary Table 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants by sex

| Men | Women | Overall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 53720 | N = 78759 | N = 132479 | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 56.7 (8.1) | 55.7 (7.9) | 56.1 (8.0) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Ethnicity | White | 51,752 (96.8) | 75,476 (96.1) | 127, 228 (96.0) |

| South Asian | 690 (1.3) | 845 (1.1) | 1,535 (1.2) | |

| Black | 417 (0.8) | 890 (1.1) | 1,277 (1.0) | |

| Chinese | 125 (0.2) | 280 (0.4) | 405 (0.3) | |

| Other | 280 (0.5) | 583 (0.7) | 863 (0.7) | |

| Mixed | 225 (0.4) | 513 (0.7) | 738 (0.6) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Anthropometric measurements | Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.7 (3.6) | 26.0 (4.6) | 26.3 (4.2) |

| % Body fat | 23.7 (5.5) | 35.1 (6.7) | 30.5 (8.4) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 94.0 (10.1) | 82.1 (11.4) | 86.9 (12.4) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| 2-4h energy intake | Sugar (kJ/day) | 2,316 (813) | 2,078 (749) | 2,175 (784) |

| Starch (kJ/day) | 2,508 (754) | 2,012 (650) | 2,213 (735) | |

| Fat (kJ/day) | 3,522 (1,057) | 2,964 (945) | 3,190 (1,029) | |

| Protein (kJ/day) | 1,578 (407) | 1,382 (354) | 1,461 (389) | |

| Fibre (g/day) | 18 (7) | 17 (6) | 18 (6) | |

| Total | 10,556 (2,112) | 8,793 (1,935) | 9,508 (2,187) | |

| 24-h energy intake | % | % | % | |

| Sugar | 22.0 | 23.7 | 23.0 | |

| Starch | 23.9 | 23.0 | 23.4 | |

| Fat | 33.2 | 33.5 | 33.3 | |

| Protein | 15.0 | 15.9 | 15.5 | |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Physical activity (METs/day) | Light | 300 (75-330) | 300 (188-450) | 300 (150-425) |

| Moderate | 87 (20-220) | 80 (20-180) | 85 (20-190) | |

| Vigorous | 40 (0-180) | 13 (0-120) | 20 (0-160) | |

| Total | 500 (300-820) | 515 (315-792) | 511 (305-807) | |

N, number; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; METs, metabolic equivalents.

All P < 0.001.

Due to missing or extreme values, we excluded 1594 (1.2%), 1676 (1.3%) and 114 (0.1%) participants from the analyses of BMI, percentage body fat and waist circumference, respectively. Based on BMI, 35 222 (66.3%) men and 40 273 (51.8%) women were either overweight or obese (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Fat was the largest contributor to total energy intake in all BMI categories (Table 2). Compared with participants with a normal BMI, those who were obese had 11.5% higher energy intake overall (Table 2). Their absolute energy intake was higher for every macronutrient. Their absolute energy intakes from fat, protein and starch were 14.6%, 13.8% and 9.5% higher, respectively; but their sugar intake was only 4.7% higher. Therefore, compared with participants with a normal BMI, the proportion of energy they obtained from fat was higher (34.3% vs 33.4%, P < 0.001) but from sugar was lower (22.0% vs 23.4%, P < 0.001). There were weak correlations between the absolute energy derived from sugar and the energy derived from starch (r = 0.16), fat (r = 0.24) and protein (0.28) (Supplementary Table 2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online); 13.2% of participants in the highest quintile for absolute energy intake from sugar were in the lowest quintile for absolute energy intake from fat, and 13.3% of those in the lowest quintile for absolute energy intake from sugar were in the highest quintile for absolute energy intake from fat (Supplementary Table 3, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Table 2.

Total and macronutrient energy intake by body mass index group

| Underweight Mean (kJ/day) (%) | Normal Mean (kJ/day) (%) | Overweight Mean (kJ/day) (%) | All obese Mean (kJ/day) (%) | Obese1 Mean (kJ/day) (%) | Obese2 Mean (kJ/day) (%) | Obese3 Mean (kJ/day) (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 109 | N = 17759 | N = 26693 | N = 8529 | N = 7234 | N = 1092 | N = 203 | ||

| Men | Sugar | 2257 (22.9) | 2298 (22.6) | 2314 (21.9) | 2361 (20.8) | 2343 (20.9) | 2417 (20.1) | 2678 (20.4) |

| Starch | 2537 (25.7) | 2495 (24.5) | 2479 (23.5) | 2627 (23.1) | 2599 (23.2) | 2754 (22.9) | 2968 (22.6) | |

| Fat | 3306 (33.5) | 3375 (33.1) | 3511 (33.3) | 3864 (34.0) | 3797 (33.9) | 4157 (34.6) | 4692 (35.8) | |

| Protein | 1410 (14.3) | 1510 (14.8) | 1577 (15.0) | 1721 (15.1) | 1694 (15.1) | 1839 (15.3) | 2044 (15.6) | |

| Total | 9876 | 10189 | 10545 | 11362 | 11215 | 12009 | 13107 | |

| N = 627 | N = 36895 | N = 27401 | N = 12872 | N = 9200 | N = 2723 | N = 949 | ||

| Women | Sugar | 2072 (24.4) | 2058 (23.9) | 2068 (23.6) | 2154 (23.0) | 2122 (23.1) | 2201 (22.8) | 2324 (22.3) |

| Starch | 2029 (23.9) | 1975 (22.9) | 1992 (22.7) | 2161 (23.0) | 2110 (23.0) | 2237 (23.2) | 2432 (23.3) | |

| Fat | 2854 (33.7) | 2883 (33.5) | 2946 (33.6) | 3238 (34.5) | 3147 (34.3) | 3375 (35.0) | 3731 (35.8) | |

| Protein | 1296 (15.3) | 1336 (15.5) | 1391 (15.9) | 1495 (15.9) | 1466 (16.0) | 1536 (15.9) | 1654 (15.9) | |

| Total | 8478 | 8608 | 8771 | 9379 | 9187 | 9657 | 10434 | |

| N = 736 | N = 54654 | N = 54094 | N = 21401 | N = 16434 | N = 3815 | N = 1152 | ||

| Overall | Sugar | 2100 (24.2) | 2136 (23.4) | 2189 (22.7) | 2236 (22.0) | 2219 (22.0) | 2263 (21.9) | 2387 (21.9) |

| Starch | 2104 (24.2) | 2144 (23.5) | 2232 (23.1) | 2347 (23.1) | 2325 (23.1) | 2385 (23.1) | 2527 (23.2) | |

| Fat | 2921 (33.6) | 3043 (33.4) | 3225 (33.4) | 3488 (34.3) | 3433 (34.1) | 3599 (34.8) | 3900 (35.8) | |

| Protein | 1313 (15.1) | 1393 (15.3) | 1483 (15.4) | 1585 (15.6) | 1567 (15.6) | 1623 (15.7) | 1723 (15.8) | |

| Total | 8684 | 9122 | 9646 | 10169 | 10080 | 10330 | 10905 |

Underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2), all obese (≥ 30.0 kg/m2), obese 1 (30.0-34.9 kg/m2), obese 2 (35.0-39.9 kg/m2), obese 3 (≥ 40.0 kg/m2).

All P < 0.001.

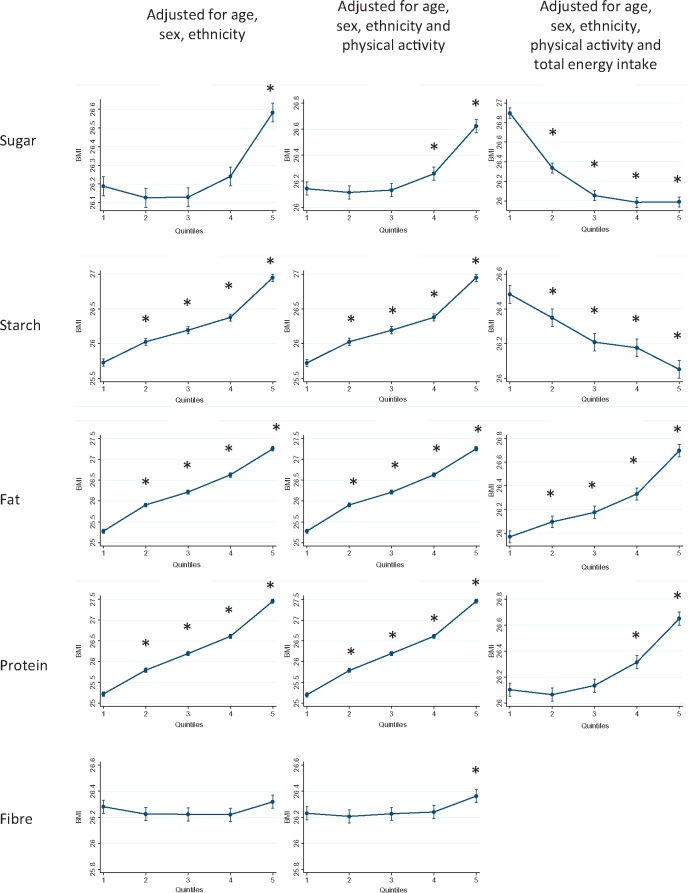

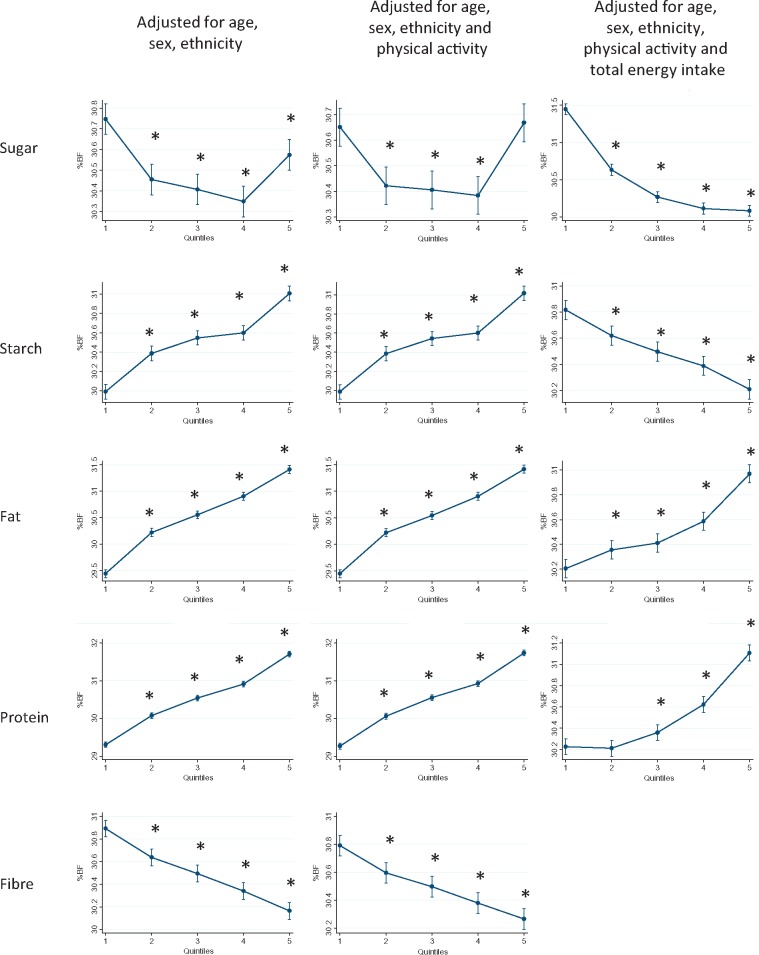

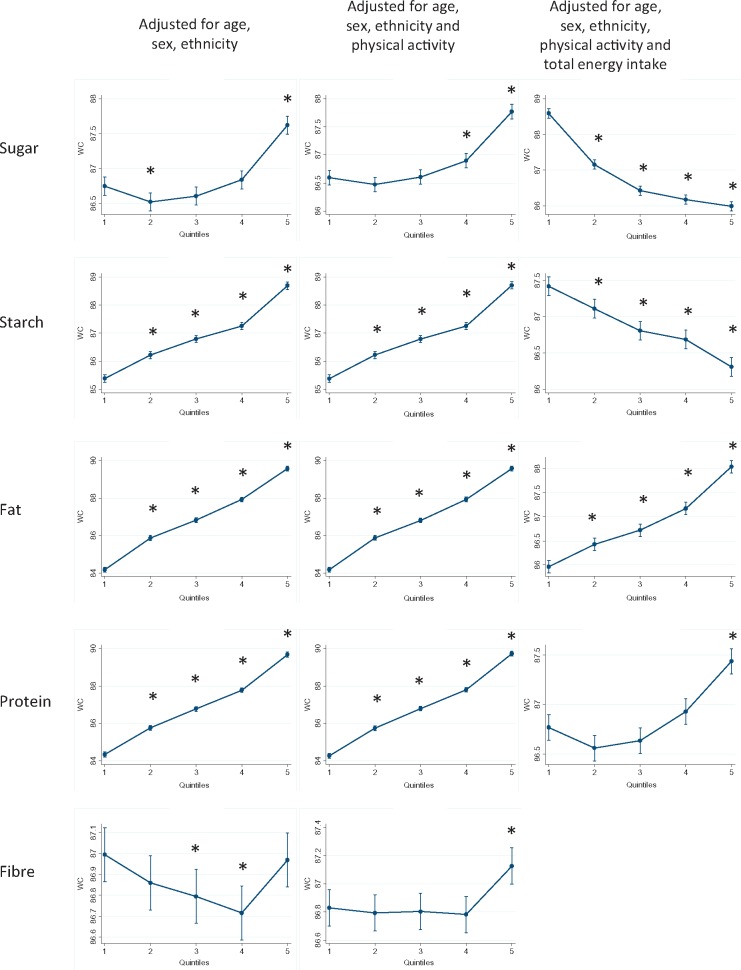

Figures 1–3 show the results of the multivariable linear regression models for BMI, percentage body fat and waist circumference, respectively. When adjusted for age, sex and ethnicity, there were clear dose relationships, across all quintiles, whereby BMI, percentage body fat and waist circumference where all higher in those with the highest consumption of starch, fat and protein. The patterns persisted after including physical activity in the models. In contrast, BMI and waist circumference were only higher in those participants whose sugar intake was in the highest two quintiles.

Figure 1.

Body mass index by quintile of absolute energy obtained from macronutrient and quintile of percentage of total energy obtained from macronutrient. *P < 0.05 referent to quintile 1.

Figure 2.

Percentage body fat by quintile of absolute energy obtained from macronutrient and quintile of percentage of total energy obtained from macronutrient. *P < 0.05 referent to quintile 1.

Figure 3.

Waist circumference by quintile of absolute energy obtained from macronutrient and quintile of percentage of total energy obtained from macronutrient. *P < 0.05 referent to quintile 1.

For fat and protein consumption, there was a positive association between the percentage of energy intake derived from these macronutrients and all three measures of adiposity (Figures 1–3). In contrast, there was a negative association with both sugar and starch. Higher adiposity was associated with lower percentage contributions from these macronutrients after taking account of potential demographic confounders and level of physical activity. There was no clear relationship between intake of fibre and BMI, and a negative association with percentage body fat.

Total energy intake was strongly associated with BMI (highest quintile adjusted coefficient 2.47, 95% CI 2.39-2.55,P < 0.001). The magnitude of the association was greater than for any individual macronutrient (Supplementary Table 4, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Of the macronutrients, the association was strongest for fat (highest quintile adjusted coefficient 1.98, 95% CI 1.91-2.06, P < 0.001) and weakest for sugar (highest quintile adjusted coefficient 0.48, 95% CI 0.41-0.55, P < 0.001). After adjusting for total energy intake, the association remained positive for fat (highest quintile adjusted coefficient 0.70, 95% CI 0.63-0.77, P < 0.001) but became negative for sugar (highest quintile adjusted coefficient −0.93, 95% CI −1.00 to −0.86, P < 0.001).

Discussion

Obesity was more strongly associated with total energy intake than the amount of energy derived from any individual macronutrients. The association between obesity and absolute energy derived from sugar was less strong than from all other macronutrients. The strongest association was with energy derived from fat. There was a positive, but weak, correlation between absolute energy derived from sugar and from other macronutrients, including fat. Fat made a greater contribution to overall energy intake than sugar in all BMI groups, but especially in the obese group. Finally, on adjusting for total energy intake, fat remained positively associated with obesity, whereas sugar was negatively associated. This implies that although obese participants had a higher absolute intake of sugar; obesity was actually associated with a lower percentage of energy intake derived from sugar.

The association between sugar intake and obesity is due to the contribution of sugar to overall energy consumption, rather than a specific effect of sugar. A meta-analysis of cohort studies showed an overall association between higher sugar consumption and higher weight, but not in the subgroup of studies that adjusted for overall energy consumption.15 Similarly, two recent systematic reviews of trials in which sugar intake was increased within the context of isocalorific diets, showed no effect on body weight.16,17 Therefore, reduction of sugar intake will be effective at reducing obesity only if associated with a reduction in overall energy intake. However, researchers have suggested there may be a ‘sugar-fat seesaw’ whereby individuals free to choose their diets compensate for a change in the consumption of one by a reciprocal change in the other.

Sadler et al.’s recent systematic review of observational studies demonstrated a strong, consistent inverse association between the percentage of total energy derived from sugar and the percentage derived from fat, corroborating the ‘sugar-fat seesaw’ hypothesis in terms of percentage contribution to energy intake.18 However, only two of the studies examined the relationship in terms of the absolute energy intake derived from sugar and from fat, and both studies showed a positive association.19,20 The correlation demonstrated (r = 0.37) was relatively weak;20 consistent with our findings.

Intervention studies have examined either weight loss interventions or dietary supplements. Of three meta-analyses published in 2013 on trials of reduced sugar intake in children, two concluded there was no impact on weight,16,21 and one reported a reduction in the fixed effects model22 but not the random effects model. A meta-analysis of five trials conducted in adults reported a reduction in weight, but highlighted the high heterogeneity between studies and the high risk of bias in three of the five studies; there was no reduction when these three studies were removed. The recent meta-analysis by Tobias et al. only compared low-carbohydrate diets with low-fat diets.23 Focusing weight loss interventions on one macronutrient may be counterproductive. Drummond and Kirk demonstrated that advising overweight men to reduce both dietary fat and dietary sugar resulted in a reduction in total energy consumed,24 whereas advising them only to reduce fat resulted in a compensatory increase in sugar consumption without a net change in overall energy intake.

Most intervention studies of dietary supplements suggested that increased consumption of one macronutrient led to a compensatory reduction in the absolute amount of other macronutrients consumed, but this was usually insufficient to obviate a net increase in overall energy intake. Reid et al. demonstrated that women given sugar-sweetened drinks compensated by a reduction in the absolute intake of both fat and protein, but nonetheless increased their overall energy intake.25 The effects were apparent irrespective of whether the drinks were labelled correctly or mislabelled as diet drinks. Conversely, women who consumed diet drinks did not modify their consumption of proteins, fats or starch, and had reduced overall energy consumption, irrespective of labelling. Raben et al. reported similar results from a study of overweight men and women.26

UK Biobank is representative of the general population in terms of age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status but is unrepresentative in terms of lifestyle. Therefore, caution should be heeded in generalizing summary statistics, such as the prevalence of obesity, to the general population. This does not detract from the ability to generalize estimates of the magnitude of associations. Our study benefited from a very large number of participants, recruited from the general population across the whole of the UK. We had sufficient power to undertake subgroup analyses by sex. We conducted a cross-sectional study and, therefore, cannot demonstrate a temporal relationship between diet and adiposity. Thus our results may underestimate the association between sugar/fat and obesity, since obese people are more likely to be on weight-reduction diets. However, the proportion of people on diets at any given time is likely to be modest and most are likely to have been excluded by removing from the analyses participants with energy intake less than 1.1 x BMR. Energy expenditure is typically > 1.35 x BMR for all activities other than bed rest.

Dietary intake was self-reported outside the clinic, which may encourage more truthful reporting, and was collected using a 24 h recall questionnaire which produces more accurate results than a food frequency questionnaire (the usual approach adopted in large-scale studies).14 Accuracy was further improved by administering the questionnaire on four occasions and deriving mean values.33 In addition, online administration of the questionnaires is expected to minimize any reporting bias due to social desirability. Since social desirability tends to result in under-reporting of energy intake, we excluded from the analyses extreme outliers. We excluded 37% of participants; this is consistent with similar studies which have excluded 21–67%.27,28 Reports of energy intake 10–40% below physiologically plausible values are common.29,30 Since under-reporting increases with body mass index,31,32 their exclusion is essential to avoid systematic errors. For example, among the 54 578 participants we excluded due to under-/over-reporting of dietary intake or smoking, obese people reported having slightly lower energy intake than people with a normal BMI (7307 vs 7315 kJ/day); this is likely to be due to either systematic errors in self-reporting or obese individuals being systematically more likely to consume atypical diets at the time of assessment, due to energy restriction diets. A third of our participants completed only one questionnaire, but sensitivity analysis demonstrated no change in the findings when these participants were excluded. Most studies of diet and adiposity are based on only BMI which does not differentiate between lean and fat body mass, whereas we could demonstrate consistent findings across several measures of adiposity, all obtained objectively via standardized techniques. We repeated all the analyses excluding the 4153 eligible participants who had prevalent diabetes, and the findings were not substantially altered.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that obesity is associated with higher sugar intake, but the association is less strong than with other macronutrients especially fat. Focusing public health interventions and messages on sugar may detract from the need to reduce overall energy consumption and could, paradoxically, increase fat consumption.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Funding

This work was supported by the Glasgow University Paterson Endowment Fund.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank resource; we are grateful to UK Biobank participants. UK Biobank was established by the Wellcome Trust medical charity, Medical Research Council, Department of Health, Scottish Government and the Northwest Regional Development Agency. It has also had funding from the Welsh Assembly Government and the British Heart Foundation. All authors had final responsibility for submission for publication.

Conflict of interest: The authors of this study have no competing interests to report.

Key Messages

Adiposity is associated with higher intake of sugar; but the association is stronger for fat intake and strongest for total energy intake.

Fat is the largest contributor to overall energy intake.

There is only a weak correlation between absolute energy derived from sugar and from fat. Therefore, targeting high-sugar consumers will not necessarily target high consumers of fat and overall energy.

Focusing public health messages on sugar consumption may mislead the public on the need to reduce fat intake and overall energy intake.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a Glance: Europe 2014. Paris: OECD, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3. An R. Prevalence and trends of adult obesity in the US, 1999-2012. ISRN Obes 2014;2014:185132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siervo M, Montagnese C, Mathers JC, Soroka KR, Stephan BC, Wells JC.. Sugar consumption and global prevalence of obesity and hypertension: an ecological analysis. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:587–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kahn R, Sievenpiper JL.. Dietary sugar and body weight: have we reached a crisis in the epidemic of obesity and diabetes? We have, but the pox on sugar is overwrought and overworked. Diabetes Care 2014;37:957–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Almiron-Roig E, Palla L, Guest K. et al. Factors that determine energy compensation: a systematic review of preload studies. Nutr Rev 2013;71:458–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scientific Advisory Committee of Nutrition. Carbohydrates and Health Report. London: Public Health England, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Collins B, Capewell S, O'Flaherty M. et al. Modelling the health impact of an English sugary drinks duty at national and local levels. PloS One 2015;10:e0130770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Buhler S, Raine KD, Arango M, Pellerin S, Neary NE.. Building a strategy for obesity prevention one piece at a time: the case of sugar-sweetened beverage taxation. Can J Diabetes 2013;37:97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bray GA, Popkin BM.. Dietary fat intake does affect obesity! Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68:1157–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu B, Young H, Crowe FL. et al. Development and evaluation of the Oxford WebQ, a low-cost, web-based method for assessment of previous 24 h dietary intakes in large-scale prospective studies. Public Health Nutr 2011;14:1998–2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldberg GR, Black AE.. Assessment of the validity of reported energy intakes - review and recent developments. Scand J Nutr 1998;42:4. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Henry CJ. Basal metabolic rate studies in humans: measurement and development of new equations. Public Health Nutr 2005;8:1133–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hebert JR, Peterson KE, Hurley TG. et al. The effect of social desirability trait on self-reported dietary measures among multi-ethnic female health center employees. Ann Epidemiol 2001;11:417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Despres JP, Willett WC, Hu FB.. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2477–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Te Morenga L, Mallard S, Mann J.. Dietary sugars and body weight: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and cohort studies. BMJ 2013;346:e7492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sievenpiper JL, de Souza RJ, Mirrahimi A. et al. Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sadler MJ, McNulty H, Gibson S.. Sugar-fat seesaw: a systematic review of the evidence. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2015;55:338–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lenders CM, Hediger ML, Scholl TO, Khoo CS, Slap GB, Stallings VA.. Effect of high-sugar intake by low-income pregnant adolescents on infant birth weight. J Adolesc Health 1994;15:596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Macdiarmid JI, Cade JE, Blundell JE.. Extrinsic sugar as vehicle for dietary fat. Lancet 1995;346:696–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaiser KA, Shikany JM, Keating KD, Allison DB.. Will reducing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption reduce obesity? Evidence supporting conjecture is strong, but evidence when testing effect is weak. Obes Rev 2013;14:620–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB.. Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:1084–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Drummond S, Kirk T.. Assessment of advice to reduce dietary fat and non-milk extrinsic sugar in a free-living male population. Public Health Nutri 1999;2:187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tobias DK, Chen M, Manson JE, Ludwig DS, Willett W, Hu FB.. Effect of low-fat diet interventions vs other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:968–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reid M, Hammersley R, Hill AJ, Skidmore P.. Long-term dietary compensation for added sugar: effects of supplementary sucrose drinks over a 4-week period. Br J Nutr 2007;97:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raben A, Vasilaras TH, Moller AC, Astrup A.. Sucrose compared with artificial sweeteners: different effects on ad libitum food intake and body weight after 10 wk of supplementation in overweight subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:721–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma Y, Olendzki BC, Pagoto SL. et al. Number of 24-hour diet recalls needed to estimate energy intake. Ann Epidemiol 2009;19:553–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang TTK, Roberts SB, Howarth NC, McCrory MA.. Effect of screening out implausible energy intake reports on relationships between diet and BMI. Obes Rev 2005;13:1205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Archer E, Hand GA, Blaire SN.. Validity of US nutritional surveillance: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey calorific intake data, 1971-2010. PLoS One 2013;8:e76632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Subar AF, Kipnis V, Troiano RP. et al. Using intake biomarkers to evaluate the extent of dietary misreporting in a large sample of adults: the OPEN study. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Redman LM, Kraus WE, Bhapkar M. et al. Energy requirements in nonobese men and women: results from CALERIE. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:71–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Livingstone MB, Black AE.. Markers of the validity of reported energy intake. J Nutr 2003;133(Suppl 3):895–920S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Westerterp KR, Goris AH.. Validity of the assessment of dietary intake: problems of misreporting. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2002;5:489–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.