In early 2015, the US city of Baltimore erupted. The precipitant of the eruption was the killing of a Black man in police custody; actually, one more killing of a Black man by police.1 But the underlying cause was inequality in social and economic conditions. It was not the whole of Baltimore that erupted – leafy Roland Park was riot-free–but the deprived inner city. Between the district with rioting and the best-off district, Roland Park, there is a 20-year gap in male life expectancy.

I wrote about the Baltimore life expectancy differences in The Health Gap.2 Although the unrest had not yet happened, it is no surprise that riots broke out in the area with worst health. Life chances are so much worse. It is unlikely that ill health is causing riots or that civil unrest is driving a 20-year gap in life expectancy. More likely, social and economic conditions shape the lives people are able to lead, and these in turn lead to inequalities in health and the likelihood of civil unrest. I describe the social determinants of health as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age; and inequities in power, money and resources that give rise to inequities in the conditions of daily life. How these social determinants lead to huge inequalities in health within and between countries, and what we can do about them, are the substance of The Health Gap.

I slipped inequalities ‘between countries’ into the previous sentence. The Health Gap deals with inequalities between, as well as within, countries for three reasons. First, it gives us perspective. A 20-year gap in life expectancy seen in Baltimore, Glasgow or the London Borough of Westminster is enormous. It is as big as the gap between women in India and women in the USA. It shows us the scale of inequalities that we are dealing with. Second, and increasingly, the health problems of middle-income countries are similar to those of high-income countries: non-communicable disease and external causes of death. It means that the causes that are relevant in one country are likely to be relevant in another. It means, further, that we can learn from experiences in different countries. If you are reading this in Canada, experience in Chile or Cuba may be relevant; if in Rio, so may Reykjavik. Middle-income countries are also characterized by a growing proportion of elderly. In low-income countries there is the additional burden of communicable disease, to which social determinants of health are highly relevant. Third, if the question is why some countries have better health than others, social determinants of health provide an important part of the answer. Such determinants may operate within a country but also may act at a global level: trade, financial flows, treaties and overseas development assistance.

Poverty in a sea of affluence

In response to the question–which is more important for health, absolute or relative poverty––I answer: both. It is instructive to contrast LeShawn growing up in the deprived Upton Druid district of Baltimore with Bobby, growing up in Roland Park.

LeShawn’s was a single-parent family, like half the others in Upton/Druid Heights. Their household income in 2010 was $17 000, the median for the neighbourhood. At school, in common with four out of ten of his classmates, he scored under the ‘proficient’ mark in reading in the third grade; and in high school he was one of the more than half of his neighbourhood who had missed at least 20 days of school a year. LeShawn completed high school, but like 90% of his neighbourhood, he did not go on to college. Each year in Upton/Druid Heights, a third of youngsters aged 10 to 17 were arrested for some ‘juvenile disorder’. A third every year means that there is little chance that LeShawn would get to the age of 17 without a criminal record, with everything that means for the future. In Upton/Druid, in the period 2005 to 2009, there were 100 non-fatal shootings for every 10 000 residents, and nearly 40 homicides.

The contrast with Bobby in Roland Park is stark. Bobby, and all but 7% of his neighbours, grew up in two-parent families, median income $90 000. Bobby was one of the 97% of his neighbourhood to achieve ‘proficient or advanced’ in the third grade reading. He was not among the 8% who missed at least 20 days a year of high school, and he was one of the three-quarters who completed college. When it comes to juvenile arrests, there are no guarantees of immunity, but the figure for Roland Park is one in 50 each year, compared with the one in three in Upton/Druid. Another stark contrast with Upton/Druid: there were no non-fatal shootings in 2005–09, and four homicides per 10 000 – one-10th of the Upton/Druid rate.

Writing from England, I cannot help but comment that had guns not been freely available, there would have been far fewer non-fatal shootings and homicides in either area. Deprivation leads to crime, but without ready access to guns, at least your violent behaviour toward your neighbours does not end up with someone getting shot.

I have ignored the fact that the population of Upton/Druid is almost exclusively Black and that of Roland Park nearly uniformly White. The determinants of health, and crime are not Blackness or Whiteness, but accumulation of disadvantage through the life course. The perspective of the ‘causes of the causes’ recognizes that advantage and disadvantage are, in the USA, closely linked with race, largely because of widespread and institutional discrimination.

These case histories help with the question of absolute versus relative poverty if we put another contrast into the mix: India. Average income per person in India at the time I was writing about Baltimore was $3 300 adjusting for purchasing power. Yet male life expectancy in India is nearly 2 years longer than in Upton Druid. The poor of Baltimore are fantastically rich compared with the average Indian but have worse health. The poor of Baltimore are deprived relative to the standards prevailing in Baltimore. This might sound as though I am coming down on the side of relative rather than absolute poverty, except that lack of money really matters to LeShawn’s mother. Lack of money influences diet, shelter, neighbourhood, the kind of care she is able to give to LeShawn, the stress she and he are under.

My resolution of apparently having it both ways comes from following Amartya Sen.3 Relative inequality with respect to income translates into absolute inequality with respect to capabilities. It is not so much what you have but what you can do with what you have. Being relatively low-income in a society where good child services are available to all, quality of schools is not dependent on the wealth of the neighbourhood, medical care is free at the point of use, public transport is available and subsidized, affordable housing is available in mixed neighbourhoods–think Norway–will be very different from being relatively low-income in a society that lacks these–think Upton Druid.

Sen speaks of having the freedom to lead a life one has reason to value. I use the term empowerment. LeShawn is disempowered in ways that matter to his health: not just relatively to Bobby, but absolutely. A disrupted childhood and living in poverty will have adverse impact on early child development. Consequent poor school performance reduces life chances in occupation, income and living conditions. A social environment that is discriminatory and fosters crime will do little for social integration. Given all of this, healthy lifestyle choices are low priority.

Not just rich and poor

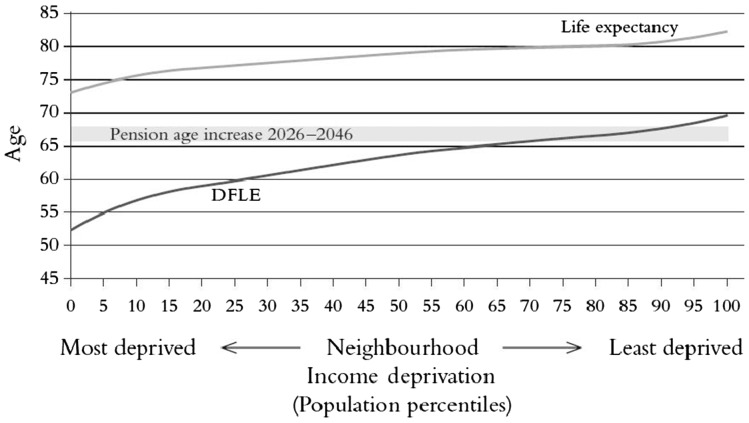

The discussion of absolute and relative poverty is highly relevant to the social gradient in health. In the Whitehall studies of British Civil Servants, with men and women classified by grade of employment, the higher the status the better the health and the longer the life expectancy. Other studies, particularly in the USA, show a gradient by years of education–more years of education, better health. Figure 1 in The Health Gap comes from the Marmot Review4 of health inequalities in England. It shows gradients in life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy according to degrees of deprivation of area of residence.

Figure 1.

Life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy (DFLE) at birth: England 1999–2003. Source: The Marmot Review (ONS).5

The gradient is important both for explanation and for policy. It is difficult to imagine that degrees of absolute deprivation account for the worse health and shorter life expectancy of people near the top, compared with those at the very top. In Sweden, for example, people with PhDs had lower mortality than those with Masters degrees or with professional qualifications. Such differences cannot be attributed to degrees of absolute deprivation in any usual sense of that word. It may relate to how relative position translates into social and psychosocial conditions.

In other words, LeShawn in Baltimore is at the end of a spectrum of disadvantage, not on a different spectrum. The scientific challenge, then, is to understand why inequalities in health run from top to bottom of the social hierarchy, and how that understanding applies to inequalities in health between countries. The Health Gap brings together evidence across the life course from individuals, communities and whole societies as to how that plays out.

For policy, the gradient is equally profound. It engages all of us. Ill health of the poor can excite prejudice: the poor are the architects of their own misfortune; worrying about them only encourages fecklessness. If of a different political persuasion, we might think that it is wrong that we organize affairs such that the poor suffer ill health, but at least we are not so affected. The gradient gives the lie to both of these. In England, people in the ‘middle’ of the social hierarchy will, on average, have 7 fewer years of healthy life than if they were at the top.

Driving home this point, in the USA the average is not healthy. The probability that a 15-year-old boy will die before his 60th birthday ranks higher than in 49 other countries. That this should be a matter of public concern was emphasized by the recent paper by Case and Deaton,6 which showed a rise in mortality rates among US Whites (non-Hispanic) aged 45–54. The fewer the years of education, the steeper the rise, thus making the social gradient steeper. Much as we are all concerned about diet and other behaviours, this was not a lifestyle issue. The causes of the rise in mortality of these 45–54 year olds were poisonings due to drugs and alcohol, suicide and chronic liver disease–presumably linked to alcohol. I describe this as disempowerment on a grand scale. Certainly it is neither an issue of lifestyle nor of medical care. The gradient involves all of us.

There’s much we can do–but we have to want to

Equity from the start–early child development and education

Inequalities in social and economic conditions through the life course are responsible for many inequalities in health. When we look at early child development, for example, we see a social gradient. I draw the parallel with Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, in which there were five castes. The Alphas and Betas were allowed to develop normally. The Gammas, Deltas and Epsilons were treated with chemicals to arrest their development intellectually and physically. The result: a neatly stratified society with intellectual function, and physical development, correlated with caste.

Should we, as in Huxley’s dystopia, tolerate a state of affairs that stratifies people, then makes it harder for the lower orders, but helps the higher orders, to reach their full potential? Were we to find a chemical in the water, or in food, that was damaging children’s growth and their brains worldwide, and thus their intellectual development and control of emotions, we would clamour for immediate action. Remove the chemical and allow all our children to flourish, not only the Alphas and Betas.

Yet, unwittingly perhaps, we do tolerate such a state of affairs. The pollutant is poverty or, more generally, lower rank in the social hierarchy, and it limits children’s intellectual and social development. The social gradient in readiness for school, as with attitudes to poverty and health, is a political litmus test. People on the right tend to blame poor parenting. Those on the left say it is social disadvantage. I say they are both correct. Social and economic conditions influence parenting.

In fact, when we plot proportion of children aged 5 years who are classified as ready for school, against deprivation of a local authority in England, we see two patterns. First is the gradient: the more deprived the local authority, the smaller the proportion of children aged 5 years with a good level of development. Second, there is scatter around the line: for a given level of deprivation, some local authorities are doing better than others. These two patterns suggest two strategies for improving early child development: reduce poverty, and support parents and families.

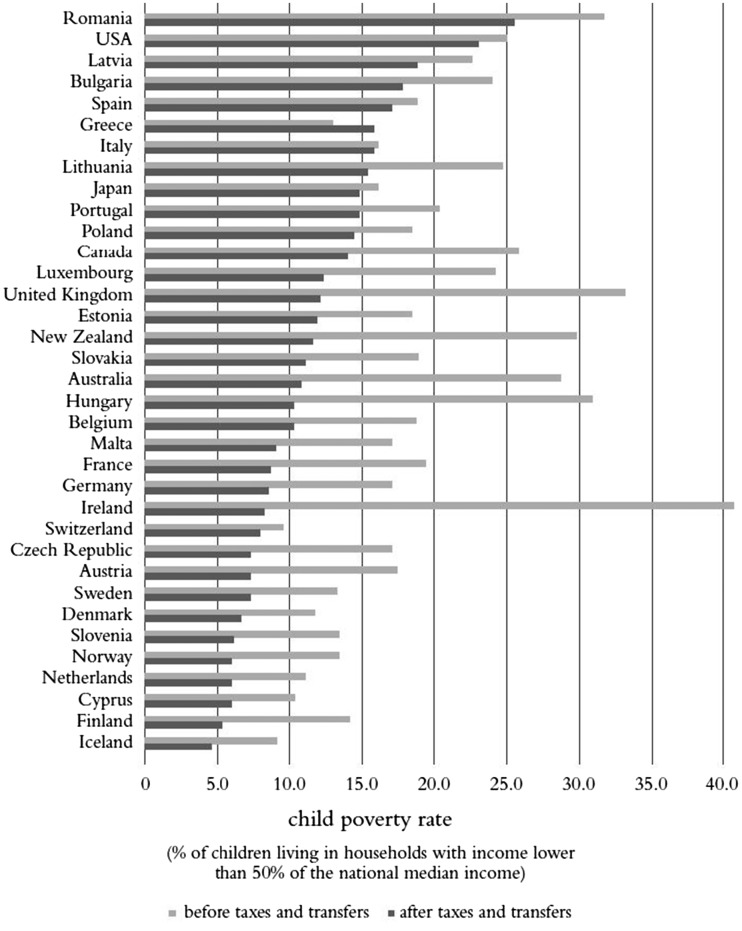

Figure 2 (Figure 4.4 from The Health Gap) shows what is possible in reducing child poverty. Romania, the USA and Latvia have similar levels of child poverty before and after taxes and transfers. The Nordic countries, The Netherlands and Slovenia are among countries that use the tax and benefit system to achieve low levels of child poverty. Other things equal, low levels of child poverty will be associated with better early child development–measures on which the Nordic countries and The Netherlands do well.

Figure 2.

Child poverty rates before taxes and transfers (market income) and after taxes and transfers (disposable income). Source: Innocenti Research Centre.7

The complementary approach is to create high quality services to support families. In the Nordic countries, with state-subsidized child care, the people who work in these services are highly trained professionals. There have also been several interventions for early childhood that have been evaluated and do indeed improve the quality of early child development. High quality early child development sets the agenda for everything that follows: better educational performance, better job, higher income, better living conditions and, as a result, better health.

We see that countries that invest in pre-school have higher performance in schools, as assessed by scores on maths and literacy in the Programme on International Student Assessment (PISA). An example of how a life course approach to adult health may play out is provided by comparison of countries in Latin America. Cuba, Costa Rica and Chile have high proportions of children enrolled in pre-school and have high reading scores on standard tests at school. At the other end of the scale, Paraguay, the Dominican Republic and Colombia have low enrolment in pre-school and less good reading scores. I note that Cuba, Costa Rica and Chile have the highest life expectancy among these countries; Paraguay, Dominican Republic and Colombia the lowest. Such comparison is hardly proof of causation, but it is consistent with a life course approach: better early child development, better educational performance, better health in adult life.

The discussion above focused on the lack of quality parenting and other positive impacts on children. There is another way to think about effects on children’s development: the bad things that can happen. A study in San Diego California was called ACE, the Adverse Child Experiences Study.8 People were asked if, during their first 18 years of life, they had experienced any of three categories of childhood abuse: psychological–being frequently put down or sworn at, or in fear of physical harm; physical; and sexual–four questions about being forced into various acts. They were also asked about four categories of household dysfunction: someone they lived with a problem drinker or user of street drugs; mental illness or attempted suicide of a household member; mother treated violently; criminal behaviour in the household.

People love to quote Nietzsche: that which does not kill us makes us stronger. It doesn’t actually. It makes us more likely to get sick. Taking those who report no adverse experiences as the reference group, compared with them, the more different types of adverse experience a person had, the greater the risk of depression and attempted suicide. People who had four or more different types of adverse childhood experience had nearly five times the risk of having spent 2 or more weeks in depressed mood the previous year, and 12 times the risk of having attempted suicide.

In general, the more types of adverse childhood experience, the more likely people were to describe themselves as alcoholic, to have injected drugs, to have had 50 or more sexual partners. Further, the more adverse experiences, the higher the risks of diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (bronchitis or emphysema), stroke and heart disease.

The ACE study was not a one-off. A review of 124 studies confirmed that child physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect (they did not study sexual abuse) are linked to adult mental disorders, suicide attempts, drug use, sexually transmitted infections and risky sexual behaviour.9 One haunting finding from the UK: half the adult perpetrators of domestic violence had been abused as children. Even more chilling: half the victims had been abused as children.10 Adverse child experiences have a long reach and they are more frequent lower down the social spectrum, thus contributing to the social gradient in adult mental and physical health.

Education and health – the slope varies

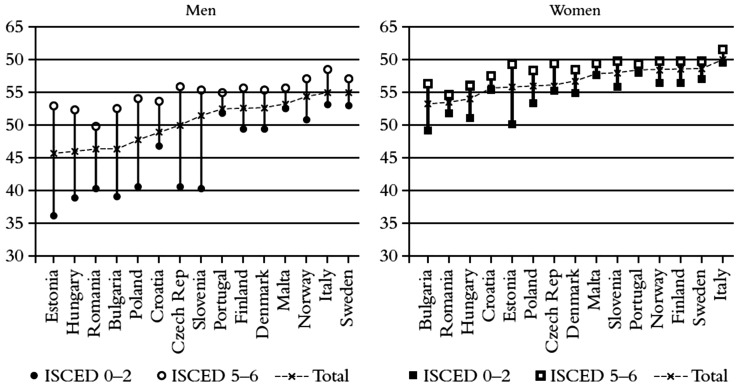

All societies have social and economic inequalities. If health were inevitably linked with position on the social hierarchy, then health inequalities would be inevitable. Probably they are, but the magnitude of the relation, the slope of the gradient, varies. This is shown by a comparison of European countries in the Figure 3 (Figure 5.4 from The Health Gap).

Figure 3.

Life expectancy at age 25 in European countries by education level ISCED, International Social Classification of Education, where 0–2 = none to lower education; 5–6 = tertiary and advanced research. Source: Eurostat.11

In Estonia, for example, average life expectancy for men at age 25 is only 45 more years, 10 years fewer than Sweden. Within Estonia, 25-year-old men with the lowest level of education have life expectancy 17 years fewer than for men with the highest level of education–sixty-one compared with 78. In Sweden, the average is higher and the gap in life expectancy between the least and most educated is about 4 years–not 17 as in Estonia. As we see in other data, the differences are smaller for women than for men.

In general, all the countries with the largest inequalities in life expectancy are in central and eastern Europe. They are the poorer countries of the region, with lowest national income, and they also tend to be those with the lowest average life expectancy. But we see something else–another gift for those who think that our health is mainly determined by the choices we make. If you are going to have the lowest level of education, you would be well advised to have it in Sweden, Italy or Norway, rather than in Estonia, Hungary or Bulgaria. Putting it the other way: if you have the lowest level of education, it really matters which country you live in. For those with the highest level of education, it matters far less. I call this ‘choice’. It is a grim mockery of choice. People have no control over where they are born, and only some control over how much education they get.

Another way of looking at the graph is that the differences in life expectancy between countries are much smaller for people with university education and much bigger for those with only primary education.

I have emphasized the life course. It is likely that education is an important predictor of adult mortality for two types of reason. First, education itself fosters life skills that will be important in different contexts. Second, education is correlated with other things in adult life that are related to better health: job, income, place of residence, esteem and relative freedom from stress. This second is the likely explanation for the narrower gap in Sweden and Norway compared with Estonia and Hungary. Being poor in Norway is associated with a good deal less deprivation than being poor in Estonia.

Working and older age

As the preceding paragraph makes clear, it is not all over when children leave school. Early life and education do indeed set people on a trajectory. But what happens during working age and at later life make important contributions to health inequalities. In The Health Gap, I place emphasis on employment and working conditions, income and services. Here, I want to take up the question of income.

Wilkinson and Pickett in The Spirit Level argue that income inequality damages the health of everyone–the gini coefficient is correlated with average health of a country.12 I find the data in Figure 3 to be a more general pattern: the lower the position in the hierarchy, the more health is damaged by living in a country with poor average health. The fact that the poor suffer more does not let income inequality off the hook. Inequalities of income may have profound effects on health in at least three ways. Consider: what do the 48 million people of Tanzania, the 7 million people of Paraguay, the 2 million people of Latvia and the 25 top-earning US hedge-fund managers (combined) have in common? They all have annual income of 21–28 billion dollars.

The first way that massive inequalities of income and wealth can lead to health inequalities is that if the rich have so much, there is less available for everyone else. I do not imagine that anyone has in mind asking the 25 top-earning hedge-fund managers to donate a year’s earnings to Tanzania, but if they did they would hardly notice, as they would collect their $24 billion the next year–and it would double Tanzania’s national income. This could potentially improve the health of Tanzanians in two ways: make individuals a bit richer and improve the public realm. Such money could pay for sewage plants and toilets, provide clean running water and clean cooking stoves, even fund a few schoolteachers’ salaries.

Within countries, too, if some people have ‘too much’, others may have too little. If ‘rewards’ to hedge-fund managers, bankers and the top 1% mean that people living in the shadows of Wall Street or the City of London have too little for a healthy life, the system has gone awry. In the USA it has been estimated that almost all the income growth between 2010 and 2012, 95% of it, went to the top 1%. At the same time, 24% of the population were in poverty–taking an OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) definition of poverty as less than 60% of the median income, after taxes and transfers. By contrast, in Denmark and Norway with much lower levels of income inequality, 13% of the population are in poverty, using the same definition. Despite living in a rich country, some people simply do not have enough to lead a healthy life–we call that the Minimum Income for Healthy Living.

Second, if too much of the money is being sequestered at the top, local and central governments may have too little to spend on pre-school education, schools, improving services and amenities for neighbourhoods–reproducing, two generations later, what in 1958 J. K. Galbraith called ‘private affluence and public squalor’. Taxation is a good source of such money. To show that there is a great deal of money about, one-third of the $24 billion income of the top 25 hedge-fund managers could fund something like 80000 New York schoolteachers.

Third, too much inequality of income and wealth damages social cohesion; increasingly the rich are separated from everyone else: separate neighbourhoods, schools, recreation, fitness centres, holidays. Lack of social cohesion is likely to damage health and increase crime. We used to hear that what was good for General Motors was good for America. Perhaps it was. It is a good deal harder to make the case that what is good for Private Equity Asset Strippers International, or Get Rich Quick Hedge Fund, or United Short Sellers, and the billionaires who lead them, is good for America.

Organization of hope

I wanted to call the book The Organisation of Misery, quoting Pablo Neruda and inviting colleagues to:

Rise up with me …

Against the organisation of misery.

The publisher said I could not give a book such a title. I proffered The Organisation of Hope. Better, said the publisher, but a bit obtuse. I compromised. I called the first chapter, The Organisation of Misery, and documented the dramatic inequalities in health within and between countries. I then bring together the evidence on what we can do through the life course to reduce avoidable inequalities in health–health inequities–starting with equity in early child development, education, working conditions and better conditions for older people. I call the last chapter The Organisation of Hope because I document examples from round the world that show we can make a difference. Such action can be at local level, in workplaces and communities, at national level and globally. We have sufficient evidence to act.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Graham D. The Baltimore Riot didn't have to happen. The Atlantic. 30 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marmot M. The Health Gap: The Challenge of an Unequal World. London: Bloomsbury, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sen A. Inequality Reexamined. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marmot M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review. London: Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marmot MG, Allen J, Goldblatt P. et al. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: Strategic Review Of Health Inequalities in England Post-2010. London: Department for International Development, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2015;112:15078–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre. Measuring Child Poverty: New League Tables of Child Poverty in the World’s Rich Countries. Florence, Italy: Innocenti Research Centre, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D. et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bellis MA, Lowey H, Leckenby N, Hughes K, Harrison D. Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. J Public Health (Oxf) 2014;36:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eurostat. Life Expectancy by Age Sex and Educational Attainment (ISCED 1997). Luxembourg: Eurostat, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wilkinson RG, Pickett K. The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better. London: Allen Lane, 2009. [Google Scholar]