Abstract

Background: Vitamin B12 (B12) and folate are essential vitamins that play important roles in physiological processes. In the general population, many studies have evaluated the association of these vitamins with clinical outcomes, yet this association in hemodialysis (HD) patients remains unclear.

Methods: We examined the association of serum folate and B12 with mortality in a 5-year cohort of 9517 (folate) and 12 968 (B12) HD patients using Cox models with hierarchical adjustment for sociodemographics, comorbidities, and laboratory variables associated with the malnutrition and inflammation complex syndrome. The associations of baseline B12 and folate (separately) with all-cause mortality were evaluated across five categories of B12 [<400 (reference), 400–<550, 550–<650, 650–<750 and ≥750 pg/mL] and folate [<6.2, 6.2–<8.4, 8.4–<11 (reference), 11–<14.3 and ≥14.3 ng/mL].

Results: The study cohort with B12 measurements had a mean ± standard deviation age of 63 ± 15 years, among whom 43% were female, 33% were African-American, and 57% were diabetic. Higher B12 concentrations ≥550 pg/mL were associated with a higher risk of mortality after adjusting for sociodemographic and laboratory variables. However, only lower serum folate concentrations <6.2 ng/mL were associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality when adjusted for sociodemographic variables [adjusted hazard ratio (95% confidence-interval): 1.18 (1.03–1.35)].

Conclusions: Higher B12 concentrations are associated with higher all-cause mortality in HD patients independent of sociodemographics and laboratory variables, whereas lower folate concentrations were associated with higher all-cause mortality after accounting for sociodemographic variables. Further studies are warranted to determine the optimal B12 and folate level targets in this population.

Keywords: folate, hemodialysis, mortality, nutrition, vitamin B12

INTRODUCTION

B vitamins, including B9 (folate) and B12 (cobalamin), are water-soluble vitamins involved in normal cell function and metabolism, and their deficiencies are associated with a number of adverse outcomes [1]. Folate plays a key role in the metabolism of nucleotides and amino acids including that of homocysteine. In addition, insufficient folate intake is linked to neural tube defects, megaloblastic anemia, coronary heart disease, and colon and breast cancers [1, 2]. B12 is a coenzyme involved in the catabolism of methylmalonic acid and homocysteine (Hcy) and B12 deficiency is also associated with megaloblastic anemia as well as neurologic and cognitive sequelae [1, 2]. Given the importance of these vitamins in cell metabolism and their relationship with adverse outcomes, the use of vitamin supplements or food fortification, especially for folate, has been recommended in many countries including the United States [3].

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are at higher risk for nutritional deficiencies due to medication interactions, dietary restrictions and malnutrition [3, 4]. Furthermore, the dialysis procedure itself may lead to vitamin B deficiencies, especially in the case of folate where its molecular size renders it capable of being cleared during hemodialysis (HD) [3]. As folate is not stored in the body in large amounts, deficiency can develop within a few weeks [3]. Previous studies have shown that serum folate concentrations are lower in HD patients in comparison with that of the general population [3]. In contrast, serum B12 concentrations in HD patients have been reported as being similar to or higher than that of the normal range due to B12's larger molecular size and its subsequent difficulty in being cleared during HD [5, 6].

Previous studies have provided an inconsistent link between folate and B12 supplementation and mortality in HD patients. A randomized controlled trial comparing high doses of vitamins B6, folate and B12 supplementation versus placebo in prevalent ESRD patients did not demonstrate reduction in all-cause mortality in the treatment group [7]. Conversely, a large cohort study of incident HD Taiwanese patients linked folate supplementation with lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk [8]. Thus it remains unclear whether baseline serum folate and B12 concentrations have an impact on survival in incident HD patients, especially for US residents where dietary fortification differs from other countries. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the association of baseline folate and B12 concentrations with mortality in a large national cohort of HD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and data source

We examined data from patients who initiated treatment at a large dialysis organization in the USA between January 2007 and December 2011 [9]. This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review committees of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA and the University of California Irvine. Given this study's large sample size, patient anonymity and nonintrusive nature, the written consent requirement was waived.

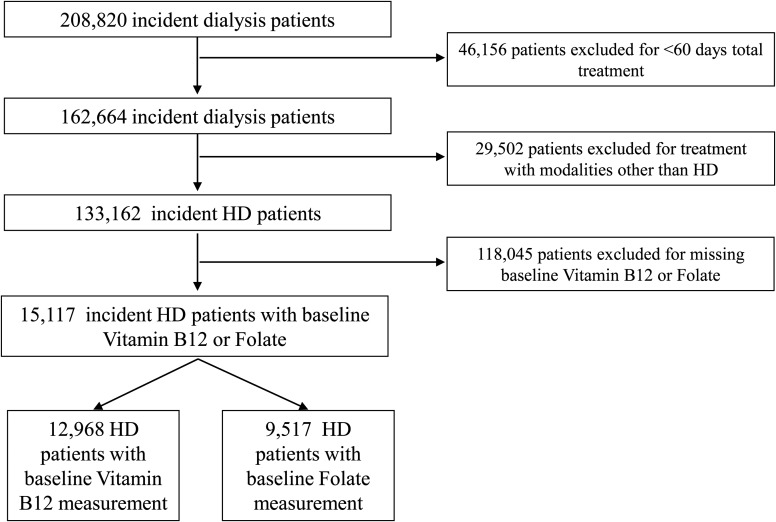

Patients were censored at the time of death, kidney transplantation, recovery of kidney function, dialysis discontinuation, transfer to a non-affiliated dialysis unit or the end of the study period (31 December 2011). Patients were excluded from this cohort if their total treatment lasted less than 60 days, they received a different dialysis modality other than in-center HD at any time during follow-up, or they did not have at least one serum vitamin B12 (B12) or folate measurement within the first 91-day period (baseline) after the start of dialysis. The final analytic cohort was composed of 12 968 patients with B12 measured and 9517 patients with folate measured (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm (flow chart) of patient selection for the cohort.

Demographic and clinical measures

Patients' sociodemographic characteristics and ICD9 codes were obtained from the large dialysis organization's electronic records database. ICD9 codes were used to determine the following comorbidities: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, other cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), substance abuse, alcohol dependence and history of cancer.

Vitamin B12, folate and other laboratory values

Serum B12 was divided into five groups (<400, 400–<550, 550–<700, 700–<950 and ≥950 pg/mL). Serum folate was divided into five groups (<6.2, 6.2–<8.4, 8.4–<11, 11–<14.3 and ≥14.3 ng/mL). Cutoffs for both exposures were determined by approximate quintiles of the cohort distribution.

Laboratory measurements were obtained using standardized and uniform techniques at all dialysis clinics and were transported typically within 24 h to a single laboratory center (DaVita Laboratory, Deland, FL, USA). All blood samples were collected pre-dialysis except for the post-dialysis serum urea nitrogen for calculation of urea kinetics. Most laboratory values were measured monthly, including serum potassium, bicarbonate, creatinine, calcium, phosphorus, intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), albumin, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), white blood cell count (WBC), hemoglobin and ferritin. To minimize the impact of short-term variability, all repeated measures during the first 91-day period of HD treatment were averaged and their summary estimates were used in all analyses.

Statistical methods

Patients' baseline demographics, clinical characteristics and laboratory measurements across serum B12 and folate categories were summarized as proportions, means ± standard deviation (SD), or median [interquartile range (IQR)] where appropriate, and were compared using a test for trend analyses, or chi-square tests where appropriate.

Cox proportional hazard models were used to separately analyze the association between the two exposures, baseline serum vitamin B12 or folate, with all-cause mortality. For each exposure, three levels of adjustment were used: (i) unadjusted models, which included adjustment for patient's calendar quarter of study entry; (ii) case-mix models, which included calendar quarter of entry, plus adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity (White, African-American, Hispanic, Asian or other), primary insurance (Medicare, Medicaid and other insurance), initial vascular access type [central venous catheter, arteriovenous (AV) fistula, AV graft, other AV and unknown], comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, atherosclerotic heart disease, congestive heart failure, other cardiovascular disease, dyslipidemia, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, HIV, substance abuse, alcohol dependence and history of cancer) and dialysis dose as indicated by single-pool Kt/V (spKt/V); and (iii) case-mix and malnutrition and inflammation complex syndrome (MICS) models, which included all of the covariates in the case-mix model, plus baseline measurements of body mass index and 13 laboratory variables associated with clinical outcomes in HD patients: serum albumin, normalized protein catabolic rate (nPCR), phosphorus, iPTH, hemoglobin, WBC ferritin, total iron binding capacity, iron saturation, creatinine, calcium, bicarbonate, and lymphocyte percentage. The association of each exposure as a continuous predictor with mortality was modeled using restricted cubic splines. Splines were examined using the three levels of adjustments as described (unadjusted, case-mix, and case-mix and MICS) with best placed knots at the 5th, 35th, 65th and 95th percentiles of each exposure. Finally, we also examined for effect modification of the association between B12 [dichotomized at the median B12 level as higher versus lower B12 (referent): ≥620 versus <620 pg/mL, respectively] and mortality across strata of demographics, comorbidities and laboratory measurements.

Data for serum creatinine, nPCR and spKt/V were missing for 4, 3 and 2% of patients, respectively. Data for all other covariates were missing for <1% of the cohort, and complete case analyses were used. All analyses were implemented using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and STATA version 13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

Serum vitamin B12 concentrations and all-cause mortality

Among 12 968 patients with at least one serum B12 measurement in the first 91 days of HD treatment, the median (IQR) serum B12 level was 620 (447–879) pg/mL. The mean ± SD age of the cohort was 63 ± 15 years, among whom 43% were female, 33% were African-American and 57% were diabetic. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients stratified across five serum B12 groups are presented in Table 1. Patients with higher serum B12 tended to be African-American, were less likely to be hypertensive, and had higher concentrations of serum calcium and ferritin.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 12 968 hemodialysis patients stratified across baseline serum vitamin B12 groups

| Serum vitamin B12 group (pg/mL) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | B12 measured | <400 | 400–<550 | 550–<700 | 700–<950 | ≥950 | P-value |

| N | n = 12 968 | n = 2304 | n = 2939 | n = 2490 | n = 2582 | n = 2653 | |

| Age (years) | 63 ± 15 | 63 ± 16 | 62 ± 15 | 62 ± 15 | 63 ± 15 | 64 ± 15 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% female) | 43 | 41 | 40 | 42 | 43 | 48 | <0.0001 |

| Race (%) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| White | 50 | 60 | 52 | 48 | 47 | 45 | |

| African-American | 33 | 24 | 30 | 34 | 36 | 38 | |

| Hispanic | 12 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 12 | 10 | |

| Asian | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Primary insurance (%) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Medicare | 55 | 52 | 54 | 54 | 54 | 58 | |

| Medicaid | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | |

| Other | 39 | 43 | 38 | 39 | 38 | 36 | |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||||||

| Hypertension | 47 | 48 | 50 | 48 | 47 | 45 | 0.0364 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 57 | 53 | 57 | 58 | 59 | 58 | 0.0005 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.8635 |

| Congestive heart failure | 37 | 37 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 37 | 0.9669 |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 16 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 0.5836 |

| Dyslipidemia | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 0.8821 |

| COPD | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 0.3620 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 15 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 0.8985 |

| History of cancer | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.3240 |

| HIV | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.8845 |

| Substance abuse | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5553 |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.9221 |

| Initial vascular access | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Central venous catheter | 73 | 68 | 73 | 74 | 76 | 76 | |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 16 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 13 | 13 | |

| Arteriovenous graft | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | |

| Other | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Folate (ng/mL) | 10.2 ± 4.3 | 9.3 ± 4.1 | 9.9 ± 4.3 | 10.2 ± 4.3 | 10.5 ± 4.3 | 11.1 ± 4.4 | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| TIBC (µg/dL) | 225.1 ± 49.3 | 229.5 ± 48.8 | 227.9 ± 46.8 | 225.9 ± 49.9 | 223.2 ± 49.3 | 219.1 ± 51.2 | <0.0001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 9.2 ± 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.1 ± 3.6 | 34.8 ± 3.6 | 35.11 ± 3.58 | 35.1 ± 3.7 | 35.1 ± 3.7 | 35.3 ± 3.6 | 0.0003 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 11.05 ± 1.16 | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 0.6363 |

| RBC (×106/µL) | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.68 ± 0.44 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 0.8331 |

| MCV (fL) | 94.0 ± 6.2 | 93.9 ± 5.7 | 93.71 ± 6.04 | 94.0 ± 6.4 | 94.0 ± 6.2 | 94.7 ± 6.4 | 0.012 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (pg) | 29.2 ± 2.2 | 29.3 ± 2.1 | 29.17 ± 2.11 | 29.2 ± 2.2 | 29.2 ± 2.2 | 29.3 ± 2.2 | 0.8299 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 31.1 ± 1.2 | 31.2 ± 1.3 | 29.17 ± 2.11 | 31.1 ± 1.2 | 31.1 ± 1.2 | 30.9 ± 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| Ferritin (µg/dL) | 293 (171–496) | 270 (160–466) | 277 (164–450) | 293 (175–498) | 305 (174–522) | 326 (191–553) | <0.0001 |

| spKt/V | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.46 ± 0.33 | 1.46 ± 0.32 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.4953 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28 ± 7 | 29 ± 7 | 29 ± 8 | 28 ± 7 | 28 ± 7 | 28 ± 8 | <0.0001 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 23.6 ± 2.7 | 23.3 ± 2.7 | 23.5 ± 2.6 | 23.7 ± 2.7 | 23.7 ± 2.7 | 24.0 ± 2.7 | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 5.9 ± 2.3 | 5.9 ± 2.3 | 5.9 ± 2.4 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | 0.0002 |

| nPCR (g/kg/day) | 0.78 ± 0.21 | 0.78 ± 0.2 | 0.78 ± 0.21 | 0.79 ± 0.22 | 0.78 ± 0.22 | 0.77 ± 0.22 | 0.3685 |

| Iron saturation (%) | 23.1 ± 9.0 | 22.8 ± 8.5 | 22.9 ± 8.19 | 22.9 ± 9.1 | 23.2 ± 8.9 | 23.8 ± 10.1 | <0.0001 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 4.95 ± 1.33 | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | <0.0001 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 313 (195–485) | 326 (208–508) | 326 (202–505) | 316 (197–488) | 309 (192–475) | 287 (172–444) | <0.0001 |

| WBC (×103/µL) | 7.8 ± 2.6 | 7.7 ± 2.4 | 7.8 ± 2.7 | 7.9 ± 2.6 | 7.9 ± 2.7 | 8.0 ± 2.7 | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 20.6 ± 7.6 | 20.5 ± 7.6 | 20.6 ± 7.5 | 20.8 ± 7.6 | 20.6 ± 7.5 | 20.5 ± 7.6 | 0.7533 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range), or proportions, and compared using a test for trend or chi-square analyses.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean cell volume; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RBC, red blood cell; spKt/V, single-pool Kt/V; TIBC, total iron binding capacity; WBC, white blood cell.

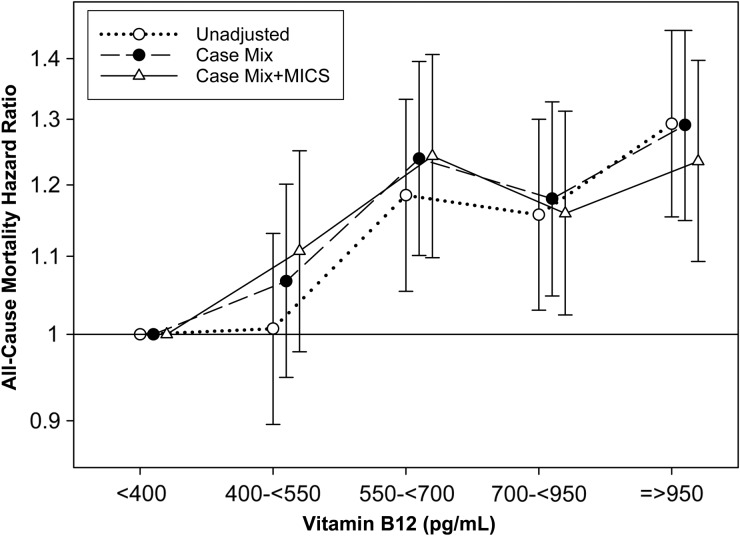

Across all levels of adjustment, baseline B12 concentrations ≥550 pg/mL were modestly, yet statistically, associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality in comparison with the reference group of serum B12 <400 pg/mL (Supplementary data, Table S1, Figure 2). B12 concentrations of 550–<700 and ≥950 pg/mL conferred the highest risks of mortality after adjusting for sociodemographic and laboratory covariates [adjusted HR (aHR), (95% confidence interval, 95% CI): 1.24 (1.10, 1.41) and 1.24 (1.09, 1.40), respectively]. Furthermore, when examined as a continuous variable using restricted cubic splines, higher B12 concentrations >400 pg/mL trended towards higher risk of mortality across all levels of adjustment (compared with referent B12 level of 400 pg/mL) (Supplementary data, Figure S1). Finally, the association between higher B12 (B12 ≥620 pg/mL) and all-cause mortality (reference: B12 <620 pg/mL) remained consistent across subgroups of sociodemographics, clinical characteristics and MICS covariates in the case-mix and MICS adjusted model, except for the subgroups of patients with and without hypertension (P-interaction = 0.01) (Supplementary data, Figure S2).

FIGURE 2.

All-cause mortality hazard ratios across baseline serum vitamin B12 groups (see text for covariate list).

Serum folate concentrations and all-cause mortality

Among 9517 patients with at least one serum folate measurement in the first 91 days of dialysis treatment, the mean ± SD serum folate level was 10.2 ± 4.3 ng/mL. The mean ± SD age of the cohort was 61 ± 15 years, among whom 43% were female, 36% were African-American and 58% were diabetic. The baseline clinical characteristics of these patients stratified across five serum folate categories are presented in Table 2. Patients with higher serum folate concentrations were more likely to be older, white, had a higher prevalence of atherosclerotic heart disease and other cardiovascular diseases, and had lower concentrations of serum creatinine.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of 9517 hemodialysis patients stratified across baseline serum folate groups

| Folate (ng/mL) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Folate measured | <6.2 | 6.2–<8.4 | 8.4–<11 | 11–<14.3 | ≥14.3 | P-value |

| n = 9517 | n = 1855 | n = 1934 | n = 1944 | n = 1911 | n = 1873 | ||

| Age (years) | 61 ± 15 | 57 ± 15 | 60 ± 15 | 60 ± 15 | 62 ± 15 | 64 ± 15 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% female) | 43 | 43 | 42 | 41 | 44 | 43 | 0.6004 |

| Race (%) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| White | 47 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 47 | 54 | |

| African-American | 36 | 42 | 38 | 35 | 34 | 29 | |

| Hispanic | 12 | 11 | 11 | 15 | 13 | 13 | |

| Asian | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Other | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| Primary insurance (%) | 0.1480 | ||||||

| Medicare | 54 | 51 | 53 | 53 | 55 | 56 | |

| Medicaid | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | |

| Other | 39 | 41 | 40 | 40 | 37 | 37 | |

| Comorbidities (%) | |||||||

| Hypertension | 47 | 49 | 48 | 46 | 47 | 47 | 0.4595 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 58 | 57 | 58 | 57 | 59 | 59 | 0.3705 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.1667 |

| Congestive heart failure | 36 | 34 | 35 | 38 | 36 | 37 | 0.1455 |

| Atherosclerotic heart disease | 15 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 0.0495 |

| Dyslipidemia | 30 | 30 | 31 | 30 | 30 | 32 | 0.6433 |

| COPD | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.9407 |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 15 | 13 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 0.0152 |

| History of cancer | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0.9199 |

| HIV | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5783 |

| Substance abuse | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2419 |

| Alcohol dependence | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4215 |

| Initial vascular access | 0.2505 | ||||||

| Central venous catheter | 76 | 77 | 76 | 75 | 74 | 76 | |

| Arteriovenous fistula | 15 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | |

| Arteriovenous graft | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | |

| Other | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 580 (425–819) | 518 (392–717) | 564 (403–774) | 579 (427–811) | 614 (456–864) | 642 (466–927) | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| TIBC (µg/dL) | 224.4 ± 49.4 | 216.6 ± 49.8 | 224.2 ± 49.8 | 227.9 ± 48.5 | 226.1 ± 47.7 | 227.1 ± 50.3 | <0.0001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 9.0 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 0.0011 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 35.1 ± 3.7 | 34.6 ± 3.8 | 35.0 ± 3.61 | 35.2 ± 3.6 | 35.2 ± 3.7 | 35.2 ± 3.6 | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 10.8 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 1.2 | 11.1 ± 1.2 | 11.1 ± 1.2 | <0.0001 |

| RBC (×106/µL) | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 0.1718 |

| MCV (fL) | 93.6 ± 6.0 | 93.9 ± 6.2 | 93.0 ± 6.5 | 93.3 ± 5.9 | 93.8 ± 5.7 | 93.9 ± 6.2 | 0.3545 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (pg) | 29.0 ± 2.1 | 29.0 ± 2.1 | 28.8 ± 2.2 | 29.0 ± 2.1 | 29.2 ± 2.0 | 29.2 ± 2.1 | 0.0025 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 31.1 ± 1.2 | 30.9 ± 1.2 | 31.0 ± 1.2 | 31.2 ± 1.3 | 31.1 ± 1.2 | 31.2 ± 1.1 | 0.0002 |

| Ferritin (µg/dL) | 290 (171–488) | 294 (171–487) | 289 (172–484) | 276 (165–473) | 291 (165–493) | 305 (179–492) | <0.0001 |

| spKt/V | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | <0.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 8 | 30 ± 8 | 29 ± 8 | 29 ± 8 | 28 ± 7 | 28 ± 7 | <0.0001 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | 23.6 ± 2.7 | 23.5 ± 2.8 | 23.7 ± 2.6 | 23.6 ± 2.6 | 23.6 ± 2.6 | 23.7 ± 2.7 | 0.0491 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 6.0 ± 2.4 | 6.2 ± 2.5 | 6.0 ± 2.4 | 6.0 ± 2.4 | 5.9 ± 2.4 | 5.7 ± 2.3 | <0.0001 |

| nPCR (g/kg/day) | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.74 ± 0.20 | 0.77 ± 0.21 | 0.78 ± 0.21 | 0.78 ± 0.21 | 0.78 ± 0.22 | <0.0001 |

| Iron saturation (%) | 23.0 ± 9.0 | 23.1 ± 9.5 | 22.9 ± 8.8 | 22.9 ± 8.7 | 23.2 ± 8.9 | 23.0 ± 8.9 | 0.8084 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.2 | 5.0 ± 1.1 | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 1.1 | <0.0001 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 336 (214–521) | 371 (232–591) | 341 (218–523) | 349 (220–538) | 327 (210–504) | 303 (196–468) | <0.0001 |

| WBC (×103/µL) | 7.8 ± 2.7 | 8.1 ± 3.0 | 7.8 ± 2.5 | 7.7 ± 2.9 | 7.7 ± 2.4 | 7.8 ± 2.5 | 0.0026 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 20.8 ± 7.5 | 21.0 ± 7.5 | 20.8 ± 7.5 | 21.1 ± 7.2 | 21.0 ± 7.7 | 20.0 ± 7.4 | 0.0019 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, median (interquartile range) or proportions, and compared using a test for trend or chi-square analyses.

BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MCHC, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean cell volume; nPCR, normalized protein catabolic rate; PTH, parathyroid hormone; RBC, red blood cell; spKt/V, single-pool Kt/V; TIBC, total iron binding capacity; WBC, white blood cell.

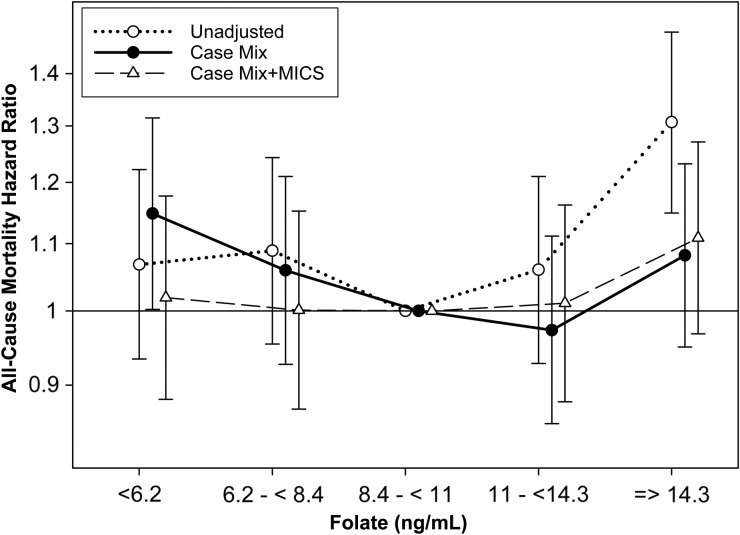

In comparison with the reference group (folate 8.4–<11 ng/mL), baseline serum folate concentrations <6.2 ng/mL were associated with a 15% higher risk of all-cause mortality after adjustment for sociodemographics and comorbid conditions [aHR, 95% CI: 1.15 (1.00–1.32)] (Supplementary data, Table S2, Figure 3). Furthermore, when examined as a continuous variable using restricted cubic splines, lower concentrations of folate <9 ng/mL were associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality after adjustment for case-mix covariates (compared with referent folate level of 8.5 ng/mL) (Supplementary data, Figure S3). However, the association of low folate and higher risk of mortality was attenuated to the null after additional adjustment for laboratory variables (Figure 3, Supplementary data, Figure S3).

FIGURE 3.

All-cause mortality hazard ratios across baseline serum folate groups (see text for covariate list).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that higher serum B12 concentrations and lower folate concentrations were modestly associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality in a nationally representative cohort of incident HD patients independent of sociodemographics and comorbidities. The B12–mortality relationship persisted after additional adjustment for surrogates of malnutrition and inflammation, whereas the addition of these covariates nullified the folate–mortality association.

Serum folate concentrations are typically low or low-normal in HD patients, particularly in patients not receiving folate supplements [6, 10, 11]. This may be due to several reasons: HD patients have reduced appetite and restricted diets, which increase the possibility of inadequate folate intake. In addition, a large proportion of HD patients have a high comorbidity burden and consume multiple medications, some of which may interfere with the absorption of nutrients and vitamins including folate [3]. Furthermore, folate is a relatively small water-soluble molecule with relatively low protein binding, and it is thus readily cleared during HD [4]. In contrast, the distribution of serum B12 concentrations in HD patients is typically similar to or higher than that of the general population [6, 10, 12]. Although B12 intake acquired through food or supplements may be reduced in HD patients, the body's capacity to store large amounts of B12 can circumvent B12 deficiency for years [3]. Unlike folate, B12 is a relatively large middle molecule and is not easily cleared during HD [4].

The modest associations of lower folate and higher B12 concentrations with higher mortality may be related to Hcy metabolism. Hcy concentrations in HD patients are found to be much higher than of the general population [10–14]. Hcy metabolism requires vitamins B6, folate and B12 (Supplementary data, Figure S4). In fact, vitamin intake is a major effect modifier of the association between Hcy and mortality in dialysis patients. In a subgroup of patients without water-soluble vitamin supplementation or folate food fortification, each 5 µmol/L increase in total Hcy was associated with a 7% higher risk of mortality. However, among patients who consumed vitamin supplements or folate-fortified food, higher Hcy was no longer associated with higher risk of mortality [15].

Our observed association between high (rather than low) B12 and mortality in HD patients is also consistent with findings in the general population. In patients with higher predisposition to inflammation, such as the HD population [16, 17], decreased production of transcobalamin II may lead to reduced uptake of circulating B12 by peripheral tissues, and heightened synthesis of transcobalamins I and III further augment accumulation of B12 in serum [18–20]. This mechanism may be an evolutionary adaptation to deter B12 away from pathogenic organisms causing inflammation and infection in peripheral tissues. Thus, in inflammatory conditions such as HD, higher circulating concentrations of serum B12 may actually indicate functional B12 deficiency in the peripheral tissues that may eventually lead to hyperhomocysteinemia, cardiovascular sequelae and death [20]. Notably, the B12–mortality association was slightly attenuated after adjusting for case-mix and MICS covariates when examined as a continuous variable (Supplementary data, Figure S1). In addition, there was a differential association among those with higher nPCR, higher serum ferritin and lower hemoglobin, which may signal populations with higher risk of inflammation (Supplementary data, Figure S2). Also, our observed B12–mortality association remained significant in those without hypertension, but it was not significant in those with hypertension (Supplementary data, Figure S2). It may be that, in those without underlying hypertension, functional B12 deficiency causes increased Hcy which promoted development of atherosclerosis, de novo vascular disease, and higher risk of cardiovascular events and death [3, 15, 21]. However, in patients who have already developed hypertension and underlying cardiovascular disease, the impact of functional B12 deficiency on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality may be negligible.

In our study, the association of low folate concentrations with mortality was attenuated with additional adjustment for surrogates of malnutrition and inflammation, whereas the B12–mortality relationship was more robust. As previously mentioned, folate concentrations are often times depleted by inadequate intake and malnutrition [3]. Thus, it is plausible that by adjusting the folate–mortality association for surrogates of malnutrition, we may have caused an over adjustment leading to a type II error. It is also possible that in our study, the main driver of mortality was not Hcy induced cardiovascular sequelae, but rather malnutrition, inflammation and protein-energy wasting (PEW) [17]. In fact, many HD patients die from PEW long before developing major cardiovascular sequelae [16]. Thus, the indicators of PEW including serum albumin may have a large bearing on the link between folate, Hcy, cardiovascular events and death in this population. Also, B12's link with mortality and its impact on the folate–mortality relationship may be because high serum B12 is not evidence of higher intake or lower excretion, but it is an indicator of significant inflammation and PEW [18, 20]. This hypothesis is also supported by prior observations of an association between serum B12 and two indicators of inflammation: C-reactive protein and ferritin. Also, Salles et al. [18] showed a similar B12–mortality relationship in elderly adults, another population predisposed to PEW [22]. However, in our study, concurrent adjustment for B12 when folate was the exposure and vice versa did not significantly change the observed associations.

Our study is subject to a number of limitations, namely that the models were only adjusted for known and measured confounders, and therefore we could not eliminate residual confounding or adjust for other factors that may influence the known confounders. In particular, our database lacked data on serum Hcy levels, the use of vitamin supplements, other inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, and possible middle molecules that may accumulate due to lack of dialysis clearance, especially in the case of B12. Also, we had no information on the cause of death and thus we could not investigate cardiovascular mortality in our study. In addition, a large proportion of patients were omitted from the cohort due to lack of folate or B12 measurement during the first 91 days of dialysis. Although this may increase risk of selection bias, a comparison of patients with or without serum B12 measurements demonstrated no clinically significant difference in baseline characteristics (Supplementary data, Table S3). B12 and folate are measured in dialysis patients to evaluate anemia through the presence of low hemoglobin or increased erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) dosage. In addition, ESA resistance is commonly found when using a central venous catheter through the presence of inflammation. There were no clinically meaningful differences between patients with and without a B12 measurement for these factors.

Despite these limitations, we had minimal measurement bias considering the fact that the dialysis facilities were under uniform administrative care and the laboratory measurements were analyzed in a single laboratory. Although the normal ranges of B12 and folate have been well documented in the general population, the ranges for the incident dialysis population remain understudied, especially for that of the US, where food fortification is in practice. To our knowledge, this is the largest study to examine the association of serum folate and B12 with mortality in a large national US cohort of incident HD patients over an extended follow-up period.

In conclusion, we observed that low serum folate and high serum B12 concentrations were modestly associated with higher all-cause mortality in incident HD patients. Additional studies are needed to investigate these relationships, especially with the inclusion of Hcy in the incident US HD population.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

M.S., H.Q., E.S., Y.O., H.M., C.M.R., C.P.K. and K.K.-Z. contributed to the study concept and design. K.K.-Z. acquired the data. M.S., H.Q. and E.S. conducted statistical analyses and interpretation with advice from Y.O., T.H.K. and K.K.-Z., M.S., S.-F.A., H.Q. and E.S. drafted the manuscript and M.S., S.-F.A., H.Q., E.S., Y.O., H.M., C.M.R., T.H.K., C.P.K. and K.K.-Z. critically revised it for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the preparation of the report and approved the final version. None of the authors reported a conflict of interest related to the study.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank DaVita Clinical Research® (DCR) for providing the clinical data for this study. The work in this manuscript has been performed with the support of the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease of the National Institute of Health research grants R01-DK95668 (K.K.-Z.) and K24-DK091419 (K.K.-Z.), R01-DK078106 (K.K.-Z.). K.K.-Z. is supported by philanthropic grants from Mr Harold Simmons, Mr Louis Chang, Dr Joseph Lee and AVEO. C.P.K. is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease grants R01-DK096920 and U01-DK102163. Y.O. has been supported by the Shinya Foundation for International Exchange of Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine Grant. C.M.R. is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease grant K23-DK102903.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

K.K.-Z. has received honoraria and/or support from Abbott, Abbvie, Alexion, Amgen, American Society of Nephrology, Astra-Zeneca, AVEO, Chugai, DaVita, Fresenius, Genetech, Haymarket Media, Hospira, Kabi, Keryx, National Institutes of Health, National Kidney Foundation, Relypsa, Resverlogix, Sanofi, Shire, Vifor and ZS-Pharma. C.P.K. has received honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis, Relypsa and ZS Pharma. K.K.-Z. has received honoraria from Genzyme/Sanofi and Shire, and was the medical director of DaVita Harbor-UCLA/MFI in Long Beach, CA during 2007–2012. Other authors have not declared any conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fairfield KM, Fletcher RH. Vitamins for chronic disease prevention in adults: scientific review. JAMA 2002; 287: 3116–3126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fletcher RH, Fairfield KM. Vitamins for chronic disease prevention in adults: clinical applications. JAMA 2002; 287: 3127–3129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clase CM, Ki V, Holden RM. Water-soluble vitamins in people with low glomerular filtration rate or on dialysis: a review. Semin Dial 2013; 26: 546–567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leblanc M, Pichette V, Geadah D et al. Folic acid and pyridoxal-5’-phosphate losses during high-efficiency hemodialysis in patients without hydrosoluble vitamin supplementation. J Ren Nutr 2000; 10: 196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fehrman-Ekholm I, Lotsander A, Logan K et al. Concentrations of vitamin C, vitamin B12 and folic acid in patients treated with hemodialysis and on-line hemodiafiltration or hemofiltration. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2008; 42: 74–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chiu Y-W, Chang J-M, Hwang S-J et al. Pharmacological dose of vitamin B12 is as effective as low-dose folinic acid in correcting hyperhomocysteinemia of hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail 2009; 31: 278–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jamison RL, Hartigan P, Kaufman JS et al. Effect of homocysteine lowering on mortality and vascular disease in advanced chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2007; 298: 1163–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chien SC, Li SY, Chen YT et al. Folic acid supplementation in end-stage renal disease patients reduces total mortality rate. J Nephrol 2013; 26: 1097–1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuttykrishnan S, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Arah OA et al. Predictors of treatment with dialysis modalities in observational studies for comparative effectiveness research. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015; 30: 1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bayes B, Pastor MC, Bonal J et al. Homocysteine, C-reactive protein, lipid peroxidation and mortality in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003; 18: 106–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dierkes J, Domrose U, Westphal S et al. Cardiac troponin T predicts mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease. Circulation 2000; 102: 1964–1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mallamaci F, Zoccali C, Tripepi G et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia predicts cardiovascular outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2002; 61: 609–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ducloux D, Klein A, Kazory A et al. Impact of malnutrition-inflammation on the association between homocysteine and mortality. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 331–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Humphreys MH et al. A low, rather than a high, total plasma homocysteine is an indicator of poor outcome in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 442–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heinz J, Kropf S, Luley C et al. Homocysteine as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in patients treated by dialysis: a meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 54: 478–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park J, Ahmadi SF, Streja E et al. Obesity paradox in end-stage kidney disease patients. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2014; 56: 415–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Obi Y, Qader H, Kovesdy CP et al. Latest consensus and update on protein-energy wasting in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2015; 18: 254–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salles N, Herrmann F, Sakbani K et al. High vitamin B12 level: a strong predictor of mortality in elderly inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 917–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seetharam B, Li N. Transcobalamin II and its cell surface receptor. Vitam Horm 2000; 59: 337–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sviri S, Khalaila R, Daher S et al. Increased Vitamin B12 levels are associated with mortality in critically ill medical patients. Clin Nutr 2012; 31: 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lim U, Cassano PA. Homocysteine and blood pressure in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 1105–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ahmadi SF, Streja E, Zahmatkesh G et al. Reverse epidemiology of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in the geriatric population. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015; 16: 933–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.