Abstract

Aims

To test the value of Periodic Repolarization Dynamics (PRD), a recently validated electrocardiographic marker of sympathetic activity, as a novel approach to predict sudden cardiac death (SCD) and non-sudden cardiac death (N-SCD) and to improve identification of patients that profit from ICD-implantation.

Methods and results

We included 856 post-infarction patients with left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤30% of the MADIT-II trial in sinus rhythm. Of these, 507 and 348 patients were randomized to ICD or conventional treatment. PRD was assessed from multipolar 10-min baseline ECGs. Primary and secondary endpoints were total mortality, SCD and N-SCD. Multivariable analyses included treatment group, QRS-duration, New York Heart Association classification, blood-urea nitrogen, diabetes mellitus, beta-blocker therapy and LVEF. During follow-up of 20.4 months, 119 patients died (53 SCD and 36 N-SCD). On multivariable analyses, increased PRD was a significant predictor of mortality (standardized coefficient 1.37[1.19–1.59]; P < 0.001) and SCD (1.40 [1.13–1.75]; P = 0.003) but also predicted N-SCD (1.41[1.10–1.81]; P = 0.006). While increased PRD predicted SCD in conventionally treated patients (1.61[1.23–2.11]; P < 0.001), it was predictive of N-SCD (1.63[1.28–2.09]; P < 0.001) and adequate ICD-therapies (1.20[1.03–1.39]; P = 0.017) in ICD-treated patients. ICD-treatment substantially reduced mortality in the lowest three PRD-quartiles by 53% (P = 0.001). However, there was no effect in the highest PRD-quartile (mortality increase by 29%; P = 0.412; P < 0.001 for difference) as the reduction of SCD was compensated by an increase of N-SCD.

Conclusion

In post-infarction patients with impaired LVEF, PRD is a significant predictor of SCD and N-SCD. Assessment of PRD is a promising tool to identify post-MI patients with reduced LVEF who might benefit from intensified treatment.

Keywords: Sudden cardiac death, Implantable cardioverter defibrillator, Risk prediction, Sympathetic nervous system, Electrocardiography

Introduction

Current guidelines suggest prophylactic implantation of a cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) in post-infarction patients with reduced left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ≤35%).1,2 This class I recommendation is based, among others, on the results of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT-II),3 which randomized high-risk post-infarction patients characterized by reduced LVEF (≤30%) to ICD and non-ICD medical therapy. Although, ICD-treatment was associated with an overall 31%-reduction in the risk of death, 17 ICDs had to be implanted to save one life.3 One important reason might be that a substantial number of patients in whom sudden cardiac death (SCD) is prevented by ICD-therapy die from non-sudden cardiac death (N-SCD). Indeed, post-hoc analyses of the MADIT-II trial showed that patients who survived an adequate shock for ventricular tachycardia (VT)/ventricular fibrillation (VF) were exposed to a markedly 3.4-fold increased risk of death within 1 year after arrhythmia termination, with a high prevalence of N-SCD.4 Early identification of these patients might help to initiate pre-emptive strategies for prevention and management of progressive left ventricular dysfunction during long-term follow-up.4

Sympathetic activation is an important compensatory mechanism of the failing heart, aiming to restore cardiac output. However, during disease progression sympathetic hyperactivity can become part of the disease, exerting own deleterious effects on the heart.5 Various studies demonstrated a strong relationship between the level of sympathetic activation and development of adverse cardiac events, including both, arrhythmic but also non-arrhythmic complications. Accordingly, assessment of sympathetic activity in MADIT-II patients might have an important prognostic meaning.

Periodic Repolarization Dynamics (PRD) is a novel electrocardiographic phenomenon that refers to previously unknown oscillations of cardiac repolarization instability.6 Those oscillations take place in the low frequency range (≤0.1 Hz), occur independently from underlying heart rate variability and can be assessed by means of a multipolar high-resolution resting electrocardiography (ECG). Although the exact mechanisms still need to be identified, electrophysiological and other studies indicated that PRD most likely reflects the effect of phasic sympathetic activation on the myocardial cells.6 In the Autonomic Regulation Trial (ART), which included 908 survivors of acute MI, increased PRD was a highly significant predictor of 5-year mortality, independently from LVEF and other established risk factors. In that study, however, the vast majority of patients (95%) had LVEF >30%. The prognostic value of PRD in post-MI patients with LVEF ≤30% is currently unknown.

In this work, we therefore tested the prognostic meaning of PRD in MADIT-II patients and hypothesized that increased PRD is a significant predictor of mortality, SCD, and N-SCD. We also hypothesized that PRD might identify patients that need intensified treatment in addition to ICD-therapy. We subsequently validated the prognostic value of PRD in predicting total mortality and cardiac mortality in a contemporary cohort of post-infarction patients with reduced LVEF.

Methods

Study populations

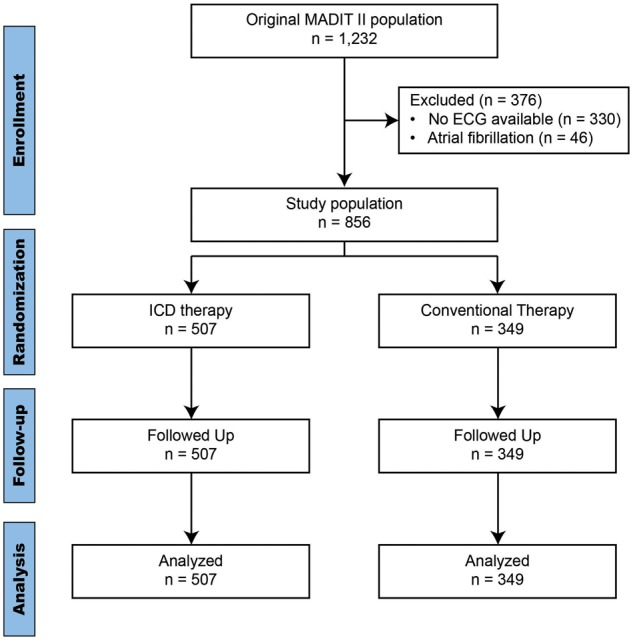

A cohort of 856 patients of the original MADIT-II population3 were included in the study. The MADIT-II trial included 1232 patients with a previous MI and a LVEF ≤30%. These patients were randomized to receive prophylactic ICD implantation or conventional medical therapy in a 3:2 ratio. Screened patients were excluded if they were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class IV at inclusion; had a MI within the last month; had undergone coronary revascularization within the preceding 3 months; had advanced cerebrovascular or renal disease and suffered from any non-cardiac condition that was associated with a high likelihood of death during the trial. A 12-lead ECG recording was acquired at baseline in supine position using a H12 + Holter device (Mortara Instrument Inc., Milwaukee, WI). This system delivers a high-resolution (1000 Hz), resting continuous ECG recording at baseline for around 10 min. Mason-Likar lead configuration was used. Medication was not changed prior to ECG-recording. Of the 1232 patients 330 patients had to be excluded because no ECG was available. Another 46 patients had to be excluded because of atrial fibrillation (Figure 1). The protocol was approved by the ethics committees of each participating centre, and each patient provided written informed consent before inclusion.

Figure 1.

Consort flow-diagram for the MADIT-II population.

The prognostic value of PRD in post-infarction patients with reduced LVEF was prospectively validated in a contemporary cohort of 153 patients who participated in the PRD-MI study (NCT02128477) and were enrolled at the university of Tuebingen between 10/2010 and 2/2014 (details presented in the Supplementary material online).

Assessment of periodic repolarization dynamics

For calculation of PRD Mason-Likar leads were transformed into Frank leads using inverse Dower’s transformation. The technical details of PRD assessment have been described elsewhere.6 Briefly, X-,Y-, and Z-leads are converted to a set of polar coordinates defined by two angles (azimuth and elevation) and the amplitude Amp. The beginning and ending of each T-wave are identified using previously published algorithms.7,8 In a second step, the spatiotemporal characteristics of each T-wave are mathematically integrated into a single vector T°, defined by the so-called weight-averaged azimuth (WAA) and weight-averaged elevation (WAE):

| (Equation 1) |

| (Equation 2) |

In a third step, the instantaneous degree of repolarization instability is estimated by the angle dT° between two successive repolarization vectors. dT° can be calculated as the scalar product of two successive repolarization vectors T°, which by two vectors of the same length can be simplified by Equation 3.

| (Equation 3) |

The spectral properties of the dT°-signal are quantified by means of continuous wavelet transformation that provides wavelet coefficients for each scale at each time point. PRD is defined as the average wavelet coefficient corresponding to frequencies of 0.1 Hz or less.6

Other risk markers

Following risk markers, that have been previously shown to be associated with outcome in the MADIT-II population9 were assessed: LVEF (continuous variable), NYHA functional class ≥II, QRS-duration (continuous variable), diabetes mellitus, treatment with beta-blockers at the time of ECG and renal dysfunction defined as blood-urea nitrogen (BUN) level >25 mg/dL. To rule out an interaction with other repolarization markers we compared PRD to Tpeak-to-Tend (TpTe), which was calculated from lead V5 as previously described.10

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was death from any cause. We also tested secondary endpoints including cardiac mortality, SCD, N-SCD, appropriate ICD therapy (A-ICD-Rx), the composite endpoint of SCD and A-ICD-Rx, and the composite endpoint of SCD, N-SCD, A-ICD-Rx, and acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations and are compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical data are presented as percentages and are analysed using the χ2 test. Multivariable analyses were implemented by the adaptation of Cox regression models. PRD was included as continuous marker. All models were adjusted for risk factors as described above. We used concordance statistic (C-index)11,12 to estimate the general predictive discrimination of the multivariable models. The coefficients of continuous variables are expressed in standardized units (increase per standard deviation [SD]). ICD efficacy was tested in PRD quartiles. Subgroup analyses were performed by means of the regression technique.13 More specifically, we used interaction terms between ICD-treatment and PRD, as well as therapy with beta-blockers and PRD in order to test the predictive power of PRD in the different subgroups. Internal validation for all endpoints was applied using bootstrapping (n = 500).12,14,15 Correlation between PRD and TpTe was assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient and was compared against zero. Differences were considered statistically significant when the two-sided P-value was <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 and CRAN R 3.2.3.

Results

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as treatment and outcome in the studied MADIT-II population. Mean age was 63 ± 11 years. Seventeen percent of the patients were females. Fifty nine percent of the patients were treated with an ICD. Sixty-four percent were treated with beta-blockers. During a mean follow-up time of 20.4 (±12.6) months, 119 patients died. One hundred and one deaths were classified as cardiac deaths. Out of them, 53 were classified as SCD and 36 as N-SCD. Twelve cardiac deaths remained unclassified. One hundred and forty-eight patients were hospitalized for ADHF.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as treatment and outcome in the MADIT-II population (n = 856)

| Patients’ characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age ≥65, n (%) | 394 (46) |

| Females, n (%) | 144 (17) |

| White race, n (%) | 737 (86) |

| NYHA classification ≥II | 529 (63) |

| LVEF <25%, n (%) | 396 (46) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 298 (35) |

| Smoking, n (%) | 690 (81) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 484 (54) |

| BUN >25 mg/dL, n (%) | 220 (26) |

| QRS Duration >120 ms, n (%) | 245 (29) |

| Treatment | |

| ICD, n (%) | 507 (59) |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 550 (64) |

| ACE Inhibitor, n (%) | 665 (78) |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 621 (73) |

| Amiodarone, n (%) | 46 (5) |

| Outcome | |

| Death, n (% 3-year rate) | 119 (23) |

| Cardiac Deaths, n (% 3-year rate) | 101 (18) |

| SCD, n (% 3-year rate) | 53 (9) |

| N-SCD, n (% 3-year rate) | 36 (8) |

| Not-specified, n (% 3-year rate) | 12 (3) |

| Non-cardiac deaths, n (% 3-year rate) | 15 (5) |

| Unclassified deaths, n (% 3-year rate) | 3 (1) |

| VT/VF, n (% 3-year rate) | 119 (35) |

| ADHF, n (% 3-year rate) | 148 (26) |

| ADHF/Death, n (% 3-year rate) | 211 (36) |

ADHF, acute decompensated heart failure; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left-ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; SCD, sudden cardiac death; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Association of periodic repolarization dynamics with clinical endpoints in the total population

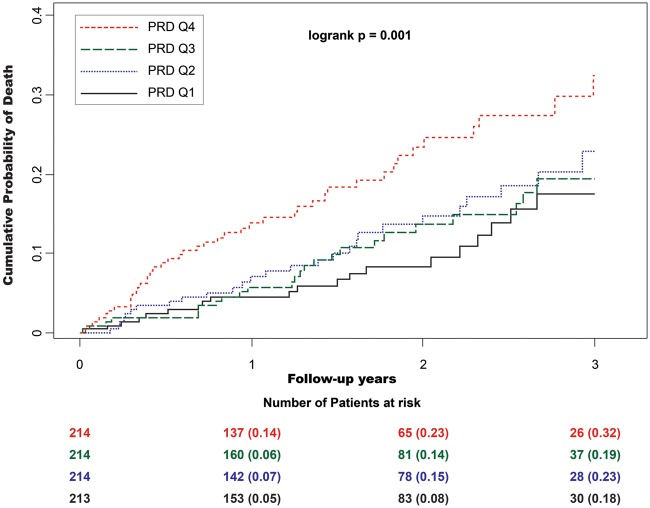

Table 2 shows the statistical association of risk variables with total mortality. Periodic repolarization dynamics was significantly higher in patients who died during the follow-up period than in those who survived (11.1 ± 7.7 deg2 vs. 8.4 ± 6.2 deg2, P < 0.001). Accordingly, increased PRD was also a significant predictor of mortality in univariable analysis, yielding a HR of 1.38 (standardized coefficient; 95% CI 1.20–1.59; P < 0.001). Figure 2 shows cumulative mortality rates of patients stratified by PRD-quartiles.

Table 2.

Statistical association of risk variables with mortality in the MADIT-II population

| Clinical characteristics | Survivors | Non-survivors | P -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 737 | 119 | |

| PRD, deg2 (SD) | 8.4 (6.2) | 11.1 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, % (SD) | 23 (5) | 22 (6) | 0.003 |

| NYHA classification ≥II, n (%) | 450 (62) | 79 (67) | 0.301 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 247 (34) | 51 (43) | 0.049 |

| BUN, mg/dL (SD) | 21 (10) | 29 (17) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 496 (67) | 54 (45) | <0.001 |

| QRS duration, sec (SD) | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.13 (0.03) | <0.001 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; LVEF, left-ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PRD, periodic repolarization dynamics; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Cumulative 3-year mortality rates in the MADIT-II population. Patients are stratified by PRD quartiles (PRD Q1 ≤4.09 deg2, PRD Q2 4.10–7.27 deg2, PRD Q3 7.28–11.51 deg2, PRD Q4 ≥11.52 deg2). Because of low number of patients with follow-up time greater than 3 years, Kaplan–Meier curves were right-censored at year 3.

Tables 3 and 4 show the association of PRD with different endpoints in multivariable analyses including established risk markers (LVEF, NYHA-classification, renal impairment, QRS-duration, treatment with beta-blockers and presence of diabetes mellitus). Increased PRD was significantly associated with all tested endpoints, including total mortality (1.37 [1.19–1.59]; P < 0.001), cardiac mortality (1.39 [1.19–1.63]; P < 0.001), SCD (1.40 [1.13–1.75]; P = 0.003), N-SCD (1.41 [1.10–1.81]; P = 0.006) as well as the combination of SCD, N-SCD, A-ICD-Rx, and ADHF (1.27 [1.15–1.41]; P < 0.001). Predictive value of PRD was also independent from that of TpTe (see Supplementary material online, Table S5). Addition of PRD improved the predictive power of the multivariable model for prediction of total mortality (increase of C-index from 0.682 [0.628–0.737] to 0.710 [0.656–0.765]), cardiac mortality (increase of C-index from 0.689 [0.632–0.747] to 0.719 [0.661–0.776]), SCD (increase of C-index from 0.652 [0.598–0.706] to 0.685 [0.631–0.740]) and N-SCD (increase of C-index from 0.653 [0.593–0.711] to 0.685 [0.629–0.742]).

Table 3.

Multivariable analyses for prediction of total mortality and cardiac mortality in the MADIT-II population

| Risk predictors | Death |

Cardiac death |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | X2 | P-value | HR (95% CI) | X2 | P-value | |

| Tx with ICD | 0.66 (0.46–0.95) | 5.0 | 0.026 | 0.57 (0.38–0.85) | 7.7 | 0.006 |

| PRD (deg2), per SD | 1.37 (1.19–1.59) | 17.7 | <0.001 | 1.39 (1.19–1.63) | 16.8 | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%), per SD | 0.91 (0.76–1.09) | 1.0 | 0.313 | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 1.4 | 0.245 |

| NYHA class ≥II | 1.08 (0.73–1.60) | 0.2 | 0.694 | 1.16 (0.76–1.78) | 0.5 | 0.500 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.17 (0.80–1.72) | 0.7 | 0.407 | 1.25 (0.83–1.89) | 1.2 | 0.281 |

| BUN >25 mg/dl | 2.26 (1.54–3.31) | 17.2 | <0.001 | 2.24 (1.48–3.39) | 14.4 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 0.63 (0.44–0.92) | 5.8 | 0.016 | 0.62 (0.42–0.93) | 5.3 | 0.022 |

| QRS (s), per SD | 1.42 (1.19–1.69) | 15.2 | <0.001 | 1.42 (1.17–1.71) | 12.8 | <0.001 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left-ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PRD, periodic repolarization dynamic; Tx, Treatment.

Table 4.

Multivariable analyses for prediction of sudden cardiac death and non-sudden cardiac death in the MADIT-II population

| Risk predictors | Sudden cardiac death |

Non-sudden cardiac death |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | X2 | P-value | HR (95% CI) | X2 | P-value | |

| Tx with ICD | 0.33 (0.19–0.58) | 14.5 | <0.001 | 1.41 (0.68–2.91) | 0.9 | 0.351 |

| PRD (deg2), per SD | 1.40 (1.13–1.75) | 9.1 | 0.003 | 1.41 (1.10–1.81) | 7.4 | 0.006 |

| LVEF (%), per SD | 0.79 (0.61–1.03) | 3.0 | 0.082 | 1.22 (0.86–1.74) | 1.2 | 0.266 |

| NYHA class ≥II | 1.31 (0.72–2.41) | 0.8 | 0.379 | 1.47 (0.68–3.17) | 0.9 | 0.330 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.25 (0.71–2.21) | 0.6 | 0.407 | 1.16 (0.58–2.31) | 0.2 | 0.684 |

| BUN >25 mg/dl | 1.71 (0.96–3.06) | 3.3 | 0.070 | 3.65 (1.79–7.41) | 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Beta-blockers | 0.68 (0.39–1.18) | 1.9 | 0.166 | 0.63 (0.32–1.25) | 1.7 | 0.189 |

| QRS (s), per SD | 1.25 (0.95–1.64) | 2.6 | 0.106 | 1.61 (1.16–2.22) | 8.3 | 0.004 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; LVEF, left-ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PRD, periodic repolarization dynamic; Tx, Treatment.

The prognostic value of PRD was internally (see Supplementary material online, Table S7) and externally validated (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2 and Table S3). In the external validation cohort, the prognostic value of PRD in predicting total and cardiac mortality was comparable to that observed in MADIT-II patients. Adding PRD to the risk prediction model improved C-statistics from 0.714 (0.582–0.892) to 0.826 (0.717–0.911) and from 0.807 (0.693–0.904) to 0.889 (0.827–0.942) for prediction of total and cardiac mortality, respectively.

Association of PRD with clinical endpoints in conventionally and ICD-treated patients

The prognostic value of PRD in predicting total mortality was present in both, the 507 patients randomized to ICD-therapy (1.40 [1.17–1.67]; P < 0.001) and the 349 patients randomized to conventional therapy (1.34 [1.06–1.69]; P = 0.014). Expectedly, the prognostic value of PRD in predicting SCD was present only in conventionally treated patients (1.61 [1.23–2.11], P < 0.001). In ICD-treated patients increased PRD did not predict SCD (1.09 [0.71–1.68]; P = 0.677) but A-ICD-Rx (1.20 [1.03–1.39]; P = 0.017). Confirmatively, in ICD-treated patients increased PRD also predicted the composite of SCD and A-ICD-Rx (1.17 [1.01–1.36]; P = 0.033) as well as the composite of all-cause mortality and A-ICD-Rx (1.21 [1.06–1.38]; P = 0.004). On the contrary, PRD was only predictive of N-SCD in ICD-treated (1.63 [1.28–2.09]; P < 0.001) but not in conventionally treated patients (0.61 [0.28–1.33]; P = 0.213).

Effect of beta-blockers

At the time of the ECG-measurement 64% of the MADIT-II patients were treated with beta-blockers. PRD was lower in patients treated with beta-blockers than in those who were not (8.13 ± 5.99 deg2 vs. 9.82 ± 8.41 deg2, P < 0.001). Nevertheless, there was no significant interaction between PRD and beta-blocker treatment for all tested endpoints (see Supplementary material online, Table S6).

Mortality reduction by ICD-treatment according to PRD values

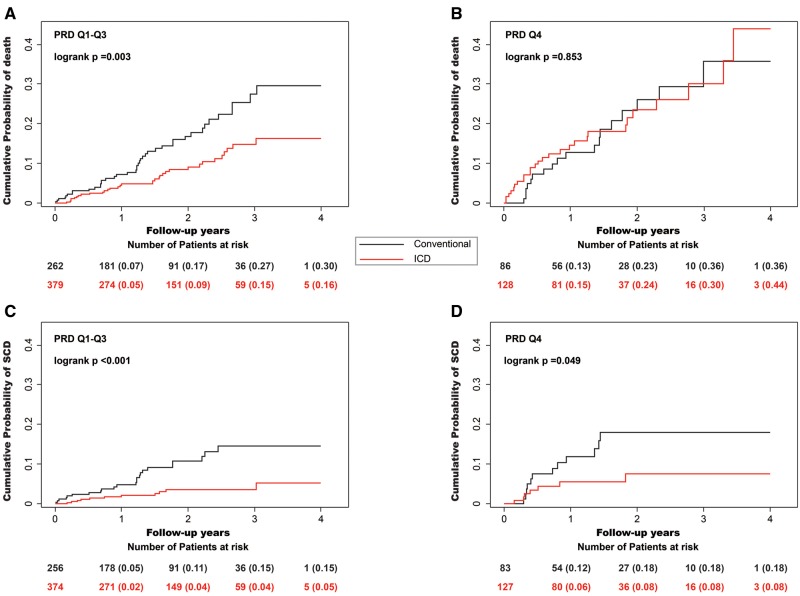

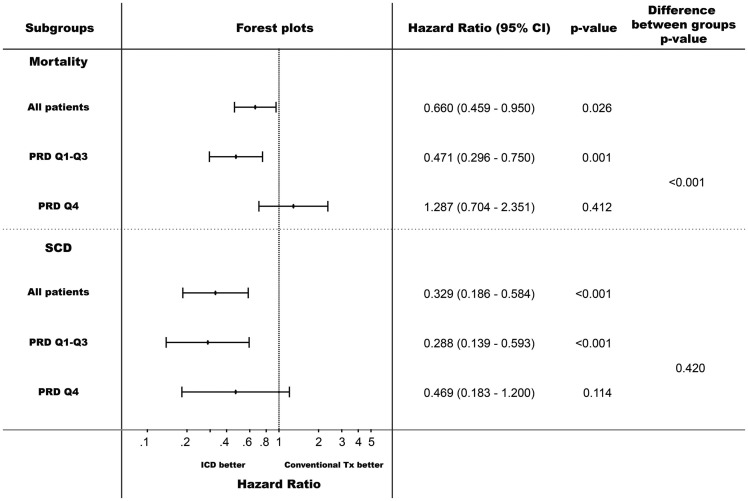

In the study population, ICD-treatment was associated with a 23.7% (95% CI 5.1–53.7%; P = 0.025) mortality reduction. As shown in Figures 3 and 4 ICD-efficacy was strikingly different in the different quartiles of PRD. In the lowest three quartiles, ICD-treatment was associated with a marked 52.9% (95% CI 25.0–70.4%) mortality reduction (P = 0.001;Figures 3A and 4) while in the highest quartile no net effect of ICD-treatment was observed (non-significant mortality increase by 28.7% [95%CI −29.6–135.1%]; P = 0.412; P < 0.001 for the difference between PRD Q1–Q3 and Q4; Figures 3B and 4). Expectedly, ICD-therapy was associated with a reduction of SCD in all PRD quartiles, which was most pronounced in the lowest three quartiles (71.2% [95% CI 40.7–86.1%] SCD-reduction in multivariable analysis; P < 0.001; Figures 3C and 4). In the highest PRD-quartile, a significant SCD-reduction was observed in univariable analysis (Figure 3D), which did not reach the level of statistical significance in multivariable analysis (53.1% [95% CI −20.0–81.7%] SCD-reduction; P = 0.114; Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Effect of ICD therapy on mortality- and sudden cardiac death- reduction (SCD) for different levels of periodic repolarization dynamics (PRD). (A) In the lowest three quartiles, ICD-treatment was associated with a mortality reduction from 30 to 16% (P = 0.003). (B) In the highest quartile no significant effect of ICD-treatment was observed (P = 0.853). ICD-therapy was associated with a reduction of SCD in all PRD quartiles (C) In the lowest three quartiles SCD was reduced from 15 to 5% (P <0.001) and (D) in the highest quartile from 18 to 8% (P = 0.049).

Figure 4.

Effect of ICD therapy on mortality- and sudden cardiac death- reduction (SCD) for different levels of periodic repolarization dynamics (PRD). Hazard ratios are calculated from multivariable models adjusted for left-ventricular ejection fraction (cont.), New York Heart Association classification ≥ II, diabetes mellitus, blood urea nitrogen >25 mg/dL, treatment with beta-blockers and QRS-duration.

Discussion

Our findings clearly demonstrate that increased PRD is a significant predictor of mortality, SCD and N-SCD in MADIT-II patients. The predictive value of increased PRD was additive to that of established risk factors that have previously been shown to be associated with outcome in the MADIT-II trial9 and was present in both, conventionally and ICD-treated patients. While increased PRD was a significant predictor of SCD in conventionally treated patients, it was predictive of N-SCD and adequate ICD-therapy for VT/VF in ICD-treated patients. There was a significant relationship between PRD-level and mortality reduction by ICD-therapy. ICD-therapy substantially reduced mortality by 53.1% in the lowest three PRD-quartiles, while there was no net effect on mortality reduction in the upper quartile, as the observed reduction of SCD was outbalanced by a compensatory increase of N-SCD. The prognostic value of PRD in predicting total and cardiac mortality was externally validated in a contemporary cohort of post-infarction patients with reduced LVEF.

Although the exact mechanisms of PRD need to be identified, previous studies suggested that PRD most likely reflects the dynamic effects of sympathetic activity on the ventricular myocardium.6 Phasic sympathetic activity predominantly takes place in the low-frequency spectral range16–20 and exerts different effects on the three cell layers of the ventricular myocardium (epicardial cells, M cells, and endocardial cells).21,22 Thus, adrenergic activation abbreviates the action potential duration (APD) of epicardial and endocardial cells to a greater degree than the APD of M cells,23 leading to an increased transmural dispersion of repolarization.24 Consequently, phasic sympathetic activation induces phasic changes in repolarization localized in the low-frequency spectral range, which might be captured by PRD. This contrasts to static measurements of spatial dispersion of ventricular repolarization such as TpTe, which showed only a very weak correlation with PRD in the present study (r = −0.12). Electrophysiological studies in healthy individuals showed that pharmacological blockade of beta-receptors resulted in a striking suppression of PRD, while physiological sympathetic activation by means of physical stress and tilt-testing caused a pronounced augmentation of PRD.6 Recently, Hanson et al. demonstrated oscillatory behaviour of ventricular APD in the same low-frequency range in heart failure patients.25 Using a modelling study the same group could show that these low-frequency oscillations were enhanced by phasic beta-adrenergic stimulation and phasic mechanical stretch. In the presence of calcium overload and reduced repolarization reserve, both characteristics of heart failure, these oscillations predisposed to early afterdepolarizations and arrhythmic events.26

So far, two clinical studies demonstrated a strong link between increased PRD resting levels and adverse events.6 Periodic repolarization dynamics was evaluated in 908 survivors of acute MI6,27 enrolled in the ART as well as in 2965 patients of The Finnish Cardiovascular Study (FINCAVAS) who underwent a clinically indicated exercise testing.6,28,29 In both cohorts, increased level of PRD was highly predictive of total mortality as well as cardiovascular mortality, independently from established risk predictors. However, patients of both cohorts substantially differ from patients of the present study. Both, the ART- and FINCAVAS-studies included low-risk patients with generally preserved LVEF (median 53 and 66%, respectively) without prophylactic ICD-indication. This is in contrast to the current study, which included high-risk patients with severely impaired LVEF in the chronic phase of MI.

In the MADIT-II trial ICD-treatment was associated with an overall 31%-reduction of total mortality. However, previous studies indicated that there is considerable risk heterogeneity within the low-LVEF group, resulting in divergent effects of ICD-therapy on mortality reduction.9 Previous studies have shown that a substantial number of patients in whom SCD has been successfully prevented by ICD-therapy subsequently die from non-sudden cardiac causes.4 Early identification of these patients is crucial for development of pre-emptive strategies against N-SCD. The results of our study show that these patients can be identified by PRD. In the present study, PRD ≥11.5 deg2 (fourth quartile) identified 25% of the patients who had the highest rates of death and SCD. However, although ICD-treated patients with PRD ≥11.5 deg2 also had the highest rates of appropriate ICD-therapies for VT/VF (33.0 vs. 20.6% in the lowest three quartiles; P = 0.004), ICD-treatment did not lead to a survival benefit in this group of patients due to an outbalancing increase of N-SCD. Importantly, this group of patients could not be identified by clinical markers, including age, gender, diabetes mellitus, NYHA-class, LVEF, renal function and QRS-duration, which were all evenly distributed (see Supplementary material online, Table S8). These findings are in line with pathophysiological considerations. It is well known that sympathetic over-activity predisposes not only to cardiac arrhythmias but also to other unfavourable cardiac conditions, including progression of heart failure and cardiac decompensation.5,30 In this context, it is noteworthy that PRD was not only predictive of N-SCD but also of ADHF. Patients with PRD in the upper quartile had 67% more ADHF than patients with PRD in the lower three quartiles (see Supplementary material online, Table S8).

Our findings have important clinical implications for post-MI management. Thus, PRD might become an important tool to stratify post-MI patients with reduced LVEF into those who already have a substantial benefit from prophylactic ICD-treatment (53.1% mortality reduction by ICD-treatment in patients with PRD <11.5 deg2) and into those who are at high competing risk of N-SCD and therefore are in need of additional pre-emptive therapies. Such strategies might include optimization of heart failure management, better monitoring and closer follow-up visits. In the studied MADIT-II patients, patients with high PRD levels were less frequently treated with beta-blockers (see Supplementary material online, Table S8). Those with high PRD-levels despite beta-blocker therapy might be undertreated. It is well known from epidemiological studies that there is a considerable risk-treatment mismatch in the pharmacotherapy of heart failure, with patients at greatest risk being least likely to receive ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers at optimal doses.31 In previous studies, we have shown that beta-blocker treatment can reduce PRD6. Therefore, PRD assessment might help to guide individualized beta-blocker therapy.

Our study has several limitations. First, we assessed PRD from 10-min recordings in Mason-Likar configuration, while in the seminal study PRD was assessed from 30-min recordings in Frank-leads configuration. Low-frequency oscillations could be underrepresented in very short-term recordings. Second, patients with atrial fibrillation were excluded from the study, as is presently unknown whether PRD can also be applied to patients with atrial fibrillation. Third, ICD-programming significantly changed over the last decade. We cannot rule out that optimized ICD-programming with longer detection intervals might have led to different findings. Fourth, patients of the MADIT-II trial did not receive medical treatment according to today’s standards. Fifth, patients in the original MADIT-II trial were followed up for a relatively short time during the trial (20.4 ± 12.6 months). Sixth, assessment of treatment effects in PRD-quartiles might be limited by small sample size. Seventh, the sample size of the validation cohort was small. Therefore, we were not able to test additional secondary endpoints. Although we also applied internal and external validation techniques to confirm our findings, further prospective studies are needed.

In conclusion, PRD is a significant predictor of mortality and SCD in the MADIT-II trial. Treatment with ICD reduced SCD-rate at all levels of PRD. However, in the highest PRD-quartile, there was no net effect of ICD-therapy on total mortality, as the reduction of SCD was outbalanced by an increase of N-SCD.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

MADIT-II was supported by a research grant from Boston Scientific Corp, St Paul, Minn, to the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry. The present study was not funded by Boston Scientific Corp. K D Rizas and A Bauer were supported for this work by grants from the EU-CERT-ICD project (Comparative Effectiveness Research to Assess the Use of Primary ProphylacTic Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators in Europe) in terms of travel cost reimbursement. Open Access was funded by the University Hospital of Munich.

Conflict of interest: Dr. Zareba reports grants from Boston Scientific, during the conduction of the MADIT-II study.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NAM, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO; American College of Cardiology Foundation, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, Heart Rhythm Society. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2013;127;e283–e352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Priori SG, Blömstrom-Lundqvist C, Mazzanti A, Blom N, Borggrefe M, Camm J, Elliott PM, Fitzsimons D, Hatala R, Hindricks G, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen K, Kuck KH, Hernández-Madrid A, Nikolaou N, Norekvål TM, Spaulding C, van Veldhuisen DJ; Authors/Task Force Members, Document Reviewers. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: The Task Force for the Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC). Eur Heart J 2015;36:2793–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML; Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002;346:877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moss AJ, Greenberg H, Case RB, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Brown MW, Daubert JP, McNitt S, Andrews ML, Elkin AD; Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-II (MADIT-II) Research Group. Long-term clinical course of patients after termination of ventricular tachyarrhythmia by an implanted defibrillator. Circulation 2004;110:3760–3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J.. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;54:1747–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rizas KD, Nieminen T, Barthel P, Zürn CS, Kähönen M, Viik J, Lehtimäki T, Nikus K, Eick C, Greiner TO, Wendel HP, Seizer P, Schreieck J, Gawaz M, Schmidt G, Bauer A.. Sympathetic activity-associated periodic repolarization dynamics predict mortality following myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest 2014;124:1770–1780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Laguna P, Jané R, Caminal P.. Automatic detection of wave boundaries in multilead ECG signals: validation with the CSE database. Comput Biomed Res 1994;27:45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pan J, Tompkins WJ.. A real-time QRS detection algorithm. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng IEEE 1985;32:230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldenberg I, Vyas AK, Hall WJ, Moss AJ, Wang H, He H, Zareba W, McNitt S, Andrews ML.. MADIT II Investigators. Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;51:288–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Panikkath R, Reinier K, Uy-Evanado A, Teodorescu C, Hattenhauer J, Mariani R, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS.. Prolonged Tpeak-to-tend interval on the resting ECG is associated with increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2011;4:441–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Steyerberg EW, Vergouwe Y.. Towards better clinical prediction models: seven steps for development and an ABCD for validation. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1925–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Harrell FE, Lee KL, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Rosati RA.. Regression modelling strategies for improved prognostic prediction. Stat Med 1984;3:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schneider B. Analysis of clinical trial outcomes: alternative approaches to subgroup analysis. Control Clin Trials 1989;10:176S–186S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harrell FE, Lee KL, Mark DB.. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harrell F. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pagani M, Montano N, Porta A, Malliani A, Abboud FM, Birkett C, Somers VK.. Relationship between spectral components of cardiovascular variabilities and direct measures of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Circulation 1997;95:1441–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Malliani A, Pagani M, Lombardi F, Cerutti S.. Cardiovascular neural regulation explored in the frequency domain. Circulation 1991;84:482–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzetti S, Rimoldi O, Furlan R, Pizzinelli P, Sandrone G, Malfatto G, Dell'orto S, Piccaluga E.. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 1986;59:178–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Montano N, Lombardi F, Gnecchi Ruscone T, Contini M, Finocchiaro ML, Baselli G, Porta A, Cerutti S, Malliani A.. Spectral analysis of sympathetic discharge, R-R interval and systolic arterial pressure in decerebrate cats. J Auton Nerv Syst 1992;40:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Furlan R, Porta A, Costa F, Tank J, Baker L, Schiavi R, Robertson D, Malliani A, Mosqueda-Garcia R.. Oscillatory patterns in sympathetic neural discharge and cardiovascular variables during orthostatic stimulus. Circulation 2000;101:886–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanabe Y, Inagaki M, Kurita T, Nagaya N, Taguchi A, Suyama K, Aihara N, Kamakura S, Sunagawa K, Nakamura K, Ohe T, Towbin JA, Priori SG, Shimizu W.. Sympathetic stimulation produces a greater increase in both transmural and spatial dispersion of repolarization in LQT1 than LQT2 forms of congenital long QT syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:911–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Antzelevitch C. Transmural dispersion of repolarization and the T wave. Cardiovasc Res 2001;50:426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C.. Cellular basis for the ECG features of the LQT1 form of the long-QT syndrome: effects of beta-adrenergic agonists and antagonists and sodium channel blockers on transmural dispersion of repolarization and torsade de pointes. Circulation 1998;98:2314–2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verrier RL, Kumar K, Nearing BD.. Basis for sudden cardiac death prediction by T-wave alternans from an integrative physiology perspective. Heart Rhythm 2009;6:416–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanson B, Child N, Van Duijvenboden S, Orini M, Chen Z, Coronel R, Rinaldi CA, Gill JS, Gill JS, Taggart P.. Oscillatory behavior of ventricular action potential duration in heart failure patients at respiratory rate and low frequency. Front Physiol Frontiers 2014;5:414.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pueyo E, Orini M, Rodríguez JF, Taggart P.. Interactive effect of beta-adrenergic stimulation and mechanical stretch on low-frequency oscillations of ventricular action potential duration in humans. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2016;97:93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barthel P, Wensel R, Bauer A, Müller A, Wolf P, Ulm K, Huster KM, Francis DP, Malik M, Schmidt G.. Respiratory rate predicts outcome after acute myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1644–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slawnych MP, Nieminen T, Kähönen M, Kavanagh KM, Lehtimäki T, Ramadan D, Viik J, Aggarwal SG, Lehtinen R, Ellis L, Nikus K, Exner DV; REFINE Risk Estimation Following Infarction Noninvasive Evaluation, FINCAVAS Finnish Cardiovascular Study Investigators. Post-exercise assessment of cardiac repolarization alternans in patients with coronary artery disease using the modified moving average method. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1130–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nieminen T, Lehtinen R, Viik J, Lehtimäki T, Niemelä K, Nikus K, Niemi M, Kallio J, Kööbi T, Turjanmaa V, Kähönen M.. The Finnish Cardiovascular Study (FINCAVAS): characterising patients with high risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2006;6:9.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pepper GS, Lee RW.. Sympathetic activation in heart failure and its treatment with beta-blockade. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee DS, Tu JV, Juurlink DN, Alter DA, Ko DT, Austin PC, Chong A, Stukel TA, Levy D, Laupacis A.. Risk-treatment mismatch in the pharmacotherapy of heart failure. JAMA 2005;294:1240–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.