Abstract

Aims

To investigate the long-term performance of the CONFIRM score for prediction of all-cause mortality in a large patient cohort undergoing coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA).

Methods and results

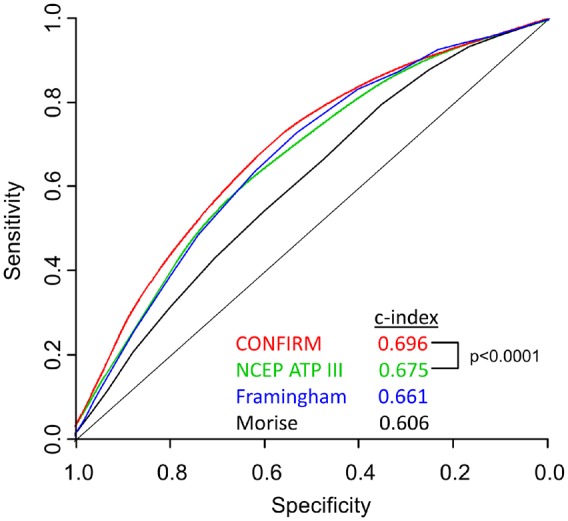

Patients with a 5-year follow-up from the international multicentre CONFIRM registry were included. The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality. The predictive value of the CONFIRM score over clinical risk scores (Morise, Framingham, and NCEP ATP III score) was studied in the entire patient population as well as in subgroups. Improvement in risk prediction and patient reclassification were assessed using categorical net reclassification index (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI). During a median follow-up period of 5.3 years, 982 (6.5%) of 15 219 patients died. The CONFIRM score outperformed the prognostic value of the studied three clinical risk scores (c-indices: CONFIRM score 0.696, NCEP ATP III score 0.675, Framingham score 0.661, Morise score 0.606; c-index for improvement CONFIRM score vs. NCEP ATP III score 0.650, P < 0.0001). Application of the CONFIRM score allowed reclassification of 34% of patients when compared with the NCEP ATP III score, which was the best clinical risk score. Reclassification was significant as revealed by categorical NRI (0.06 with 95% CI 0.02 and 0.10, P = 0.005) and IDI (0.013 with 95% CI 0.01 and 0.015, P < 0.001). Subgroup analysis revealed a comparable performance in a variety of patient subgroups.

Conclusions

The CONFIRM score permits a significantly improved prediction of mortality over clinical risk scores for >5 years after CCTA. These findings are consistent in a large variety of patient subgroups.

Keywords: Coronary Artery Disease, Cardiac computer tomographic angiography, Prognosis

Introduction

Nowadays coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is a clinically widely used tool for patients with suspected coronary artery disease (CAD) and a low-to-intermediate pre-test probability providing anatomical information at reasonable radiation dose levels.1–3 Beside its utility for the detection and exclusion of CAD, CCTA findings correlate with clinical outcome.4–8 In comparison to other diagnostic tools for the investigation of suspected CAD, CCTA is able to visualize beginning atherosclerotic vessel alterations earlier compared with other non-invasive imaging modalities and therefore might be able to identify patients at higher risk earlier.9 Various approaches to identify high-risk patients based on CCTA findings have been proposed so far, mainly focussing on coronary artery disease burden, luminal obstruction degree, and plaque composition.4–7,10

Recently, a score combining established clinical risk parameters and the presence of non-obstructive proximal mixed or calcified plaques as well as proximal lumen narrowing of ≥50% was developed from the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicenter) population.4 This score significantly improved prediction of all-cause mortality over clinical risk scores alone. However, the analysis was limited to a follow-up period of 2.3 years, and the mortality rate was low. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to investigate whether the improved risk prediction can be extended to a longer follow-up period and whether the predictive value is maintained in certain patient subgroups including patients with and without statin treatment at baseline.

Methods

Study population

The CONFIRM registry is an international, multicentre, observational registry collecting clinical, procedural, and follow-up data of patients undergoing CCTA for clinically indicated reasons.11 Patients were enrolled at 21 participating study sites in nine countries (Austria, Canada, Germany, Israel, Italy, Portugal, South Korea, Switzerland, and the USA). Institutional review board approval was obtained at each centre. Our analysis included all patients from the CONFIRM registry with suspected but not proven CAD, of whom luminal stenosis as well as presence and composition of plaque in CCTA on a segment-basis was reported, and a 5-year follow-up was available. The exclusion criterion of known CAD was defined as patient reported past myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, or the presence of any stents or grafts/graft stenosis as recorded by CT findings.

For every patient, a structured interview was conducted prior to CCTA to collect information on symptoms attributable to cardiac disease and the presence of cardiovascular risk factors. Diabetes mellitus was defined by diagnosis of a physician and/or the use of insulin or oral antidiabetic medication. Systemic arterial hypertension was defined as a documented history of blood pressure >140 mm Hg or treatment with antihypertensive medications. A positive smoking history was defined as current smoking or cessation of smoking within 3 months of CCTA. A positive family history of CAD was defined as history of myocardial infarction of a first-degree relative below the age of 55 years for male and 65 years for female relatives. In addition, blood cholesterol levels of the lipid test nearest to the index examination were recorded. From these data, the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) (NCEP ATP III) score, the Framingham risk score, and the Morise clinical risk score were calculated.12–14

Image acquisition and analysis

The imaging protocols adhered to the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography guidelines on appropriateness and performance of CCTA, as far as available at the time of scanning.15–17 Patient preparation, data acquisition, and analysis were executed as established at the local study sites. CCTA investigations were performed on multiple-row detector CT scanners with at least 64 simultaneously acquired slices.

The presence of coronary artery plaque and degree of luminal obstruction were assessed visually at the local study sites using a 16-segment coronary artery model.18 Coronary plaques were classified as non-calcified, calcified, or mixed for each coronary artery segment. Calcified plaques were defined as any visible calcification in CCTA datasets. Non-calcified plaques were defined as a tissue structure of at least 1 mm2 that could be clearly discriminated from the vessel lumen and surrounding tissue with a density below the contrast-enhanced blood pool. Plaques meeting both the criteria for calcified and non-calcified plaques were classified as mixed plaques. Luminal obstruction was graded for each segment as none, mild (1–49%), moderate (50–69%), and severe (70% or more). For the CONFIRM score, the degree of luminal obstruction was dichotomized to obstruction <50% or 50% and above.

The segment-stenosis score and segment-involvement score were calculated as proposed by Min et al. and the adapted Leaman score was calculated as proposed by Goncalves et al.7,19

Follow-up and study endpoint

The endpoint of the study was time to death from any cause. In U.S. sites, death status was ascertained by querying the Social Security Death Index. In non-U.S. sites, follow-up data were collected by mail or telephone contact with the patients or their families; events were verified by hospital records or contacts with the attending physician.

CONFIRM Score

The score was initially modelled based on a test sample of 17 793 patients and a validation sample of 2506 patients. Three parameters are incorporated into the score. To integrate the clinical risk, the NCEP ATP III score is included. Furthermore, the number of proximal segments containing calcified or mixed plaques and the number of proximal segments containing a stenosis of at least 50% luminal obstruction obtained from the CCTA scans are included. Proximal segments included left main coronary artery, proximal and mid left anterior descending artery, proximal left circumflex artery, first obtuse marginal branch, and the proximal and mid right coronary artery. The detailed process is described elsewhere.4

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages; continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile ranges as appropriate. All statistical evaluations are based on survival with the Kaplan–Meier method; hazard ratios (HRs) in continuous variables refer to 75th and 25th percentile values and like multivariable analyses were calculated with the Cox proportional hazard model. c-indexes were calculated from time-to-event data as proposed by Harrell et al.20c-index for improvement was calculated analogously using the first test as reference instead of a random guess as in standard c-statistics. To assess reclassification, categorical net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) were calculated based upon the risk categories of the NCEP ATP III score. The statistical package R (version 2.10.1) including the package rms was used for statistical analysis.21

Results

A 5-year follow-up was available in 17 179 patients enrolled at 21 participating centres. Of those, 1525 had to be excluded because of known CAD and 435 patients had to be excluded because of missing information about stenosis severity or plaque composition. The final study population comprised 15 219 patients (55.9% males), of which 10 186 belonged to the test or validation sample of the initial study population used for modelling the score. Five thousand and thirty-three additional patients were enrolled at seven centres which joined the CONFIRM consortium at a later time point.4 Analysis is based on 75 250 cumulative patient years.

Mean patient age was 58.7 ± 12.8 years. The dominating cardiovascular risk factors were arterial hypertension (54.7%) and hyperlipoproteinemia (55.5%). Information about statin and aspirin treatment at the time of CCTA acquisition was recorded in 6858 (45.1%) and 6825 (44.9%), respectively. All baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The pre-test risk was predominately low when assessed with the NCEP ATP III score or Framingham score and predominately intermediate when the Morise score was calculated (see also Table 2). During a median follow-up period of 5.3 [4.6; 5.9] years, 982 patients died, corresponding to an annual event rate of 1.3% (95% confidence intervals (CIs) 1.2 and 1.4%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Number of patients, n | 15 219 |

| Age | 58.7 ± 12.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 ± 5.1 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 8515 (55.9) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 8318 (54.7) |

| Hyperlipoproteinemia, n (%) | 8445 (55.5) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 194 ± 45 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 116 ± 37 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 53 ± 17 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 2618 (17.2) |

| Positive family history for CAD, n (%) | 6120 (40.2) |

| Active smoker, n (%) | 3284 (21.6) |

| Statin treatment | 2475 (36.1) |

| Aspirin treatment | 2521 (36.9) |

| Angina pectoris | |

| Non-anginal chest pain | 2091 (15.4) |

| Atypical Angina | 4706 (34.6) |

| Typical Angina | 3800 (27.9) |

Values are means with SD or numbers (%). Information about medical treatment at baseline was recorded in 6825 (Aspirin) and 6858 (statins) patients.

Table 2.

Performance of clinical risk scores for the prediction of all-cause mortality

| Score | Survival (n = 14 237) | Death (n = 982) | Hazard ratio [95% CI] | χ2 | c-index | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCEP ATP III | 9.8 ± 8.8 | 15.6 ± 11.2 | 1.76 [1.67; 1.86] | 421 | 0.675 | <0000.1 |

| Low risk | 8316 (58.4) | 333 (33.9) | ||||

| Intermediate risk | 2874 (20.2) | 233 (23.7) | ||||

| High risk | 3047 (21.4) | 416 (42.4) | ||||

| Framingham risk | 14.3 ± 11.2 | 20.7 ± 15.9 | 1.51 [1.44; 1.58] | 276 | 0.661 | <0000.1 |

| Low risk | 6226 (44.1) | 306 (31.3) | ||||

| Intermediate risk | 4730 (33.5) | 263 (26.9) | ||||

| High risk | 3163 (22.4) | 409 (41.8) | ||||

| Morise | 11.7 ± 3.3 | 13 ± 3.1 | 1.64 [1.51; 1.77] | 149 | 0.606 | <0000.1 |

| Low risk | 2385 (16.8) | 63 (6.4) | ||||

| Intermediate risk | 10 103 (71) | 705 (71.8) | ||||

| High risk | 1749 (12.3) | 214 (21.8) |

Values are mean with SD or numbers (%). Hazard ratios were calculated for the 75th and 25th percentile.

Predictive value of clinical risk scores

All three clinical risk scores significantly correlated with all-cause mortality (Table 2). The NCEP ATP III score performed best (c-index 0.675), followed by the Framingham score (c-index 0.661) and the Morise score (c-index 0.606).

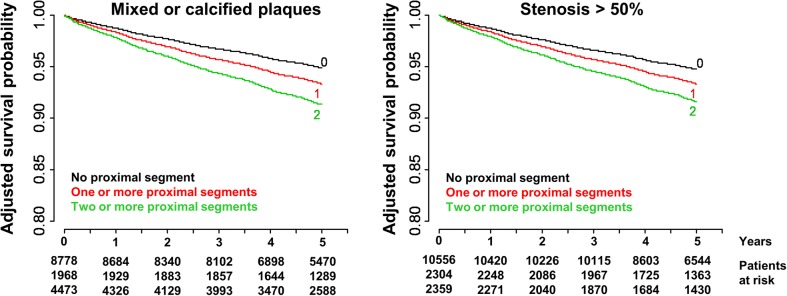

Predictive value of CCTA findings

Both the presence of any proximal non-obstructive calcified or mixed plaque and the presence of any proximal stenosis correlated significantly with clinical outcome (c-index 0.691 and 0.684, respectively, see also Table 3). Hazard ratios were 2.34 (95% CI 2.04 and 2.68) for proximal non-obstructive calcified or mixed plaques and 1.51 (95% CI 1.41 and 1.63) for any proximal stenosis. The prediction of all-cause mortality remained significant for both CCTA parameters after correction for clinical risk according to the NCEP ATP III score (c-index for improvement 0.566, P < 0.0001 and c-index for improvement 0.535, P < 0.01). Kaplan–Meier curves adjusted for clinical risk are presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Predictive value of the components integrated into the CONFIRM score

| CONFIRM score component | Survival (n = 14 237) | Death (n = 982) | Hazard ratio [95% CI] | χ2 | Univariate model |

Multivariate model |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c-index | P-value | c-index | P-value | |||||

| NCEP ATP III score | 9.8 ± 8.8 | 15.6 ± 11.2 | 1.76 [1.67; 1.86] | 421 | 0.675 | <0.0001 | n. a. | n. a. |

| Proximal segments containing non-obstructive mixed or calcified plaques | 0.7 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 2.34 [2.04; 2.68] | 147 | 0.691 | <0.0001 | 0.566 | <0.0001 |

| Proximal segments containing >50% luminal obstruction | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 1.51 [1.41; 1.63] | 126 | 0.684 | <0.0001 | 0.535 | 0.0021 |

The multivariate model was corrected for clinical risk according to the NCEP ATP III score.

Figure 1.

Risk-adjusted survival probability for the number proximal segments containing mixed or calcified plaques (left) and stenosis >50% (right). The National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) score was used for risk adjustment.

Predictive value of the CONFIRM score and risk reclassification

The CONFIRM score combining clinical risk factors and CCTA parameters revealed the best correlation with all-cause mortality (c-index 0.696, HR 2.86 with 95% CI 2.58 and 3.18). When comparing c-indexes, the prediction of all-cause mortality was significantly better with the CONFIRM score compared with NCEP ATP III score (c-index for improvement 0.650, P < 0.0001, see also Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristics curves of three clinical risk scores (Morise score, Framingham score, and NCEP ATP III score) and the CONFIRM score for all-cause mortality. NCEP ATP III depicts National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III).

The CONFIRM score provided a significantly better prediction of all-cause mortality in comparison to CCTA-based risk scores (c-indices for segment-stenosis score, segment-involvement score, and Leaman score were 0.653, 0.648, and 0.646, respectively, P < 0.001 for comparison of all scores to the CONFIRM score).

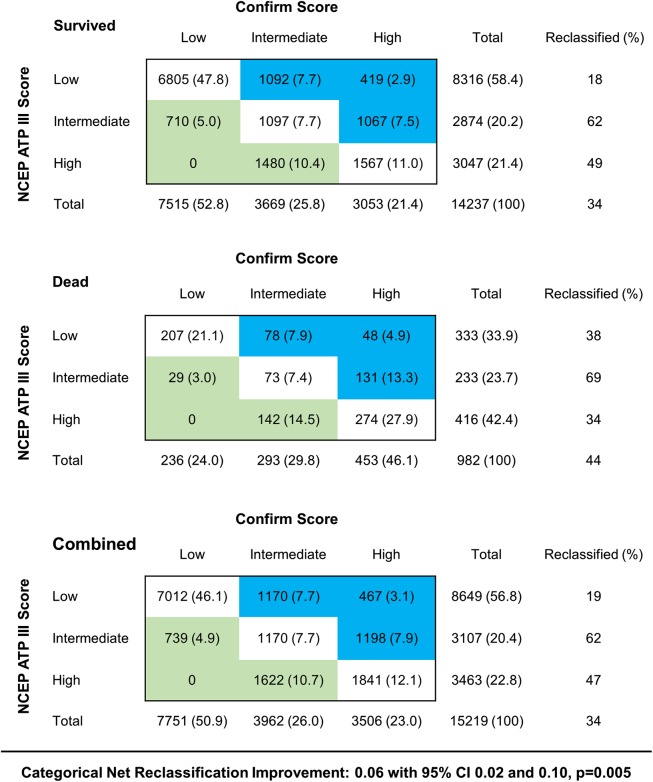

Using the CONFIRM score, a large proportion of patients (34%) could be reclassified regarding their 5-year mortality risk in comparison to the NCEP ATP III score. Categorical NRI (0.06 with 95% CI 0.02 and 0.10, P = 0.005) and IDI (0.013 with 95% CI 0.01 and 0.015, P < 0.001) proved that reclassification was significant. Reclassification for the entire population is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Reclassification tables comparing the CONFIRM and National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) score (NCEP ATP III score) in patients, who survived during follow-up, died during follow-up and combined. Light blue and light green shading indicate upward and downward risk reclassification with the CONFIRM score, respectively.

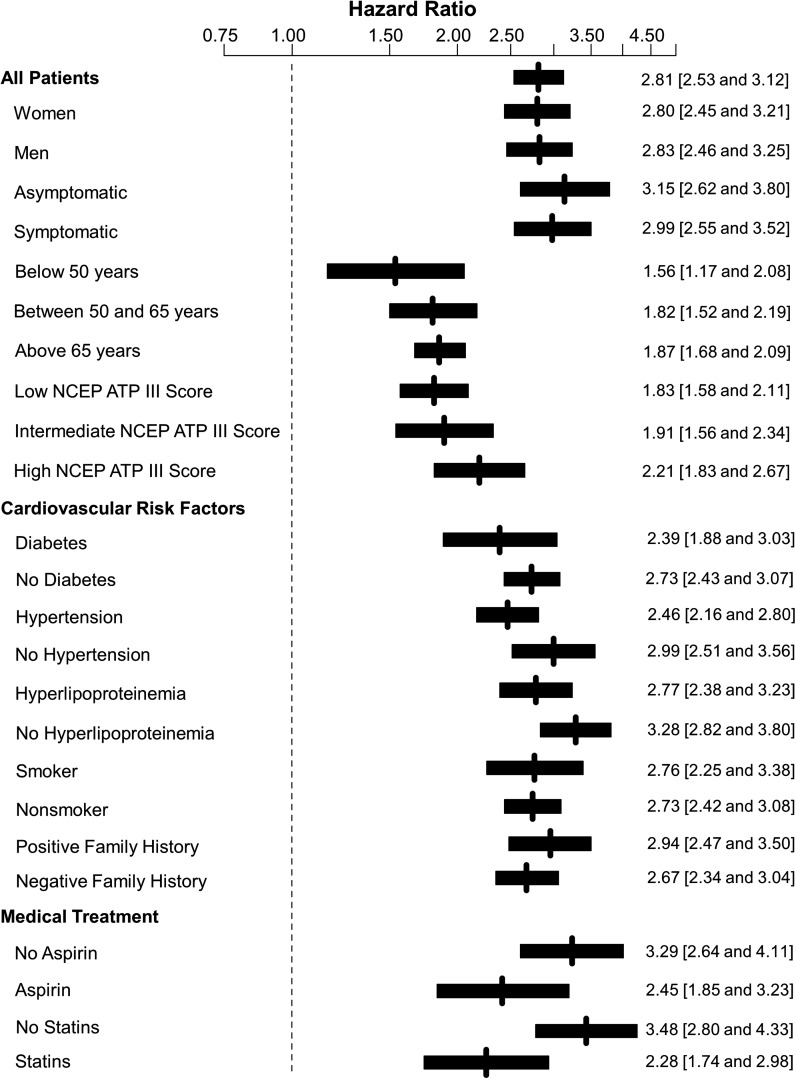

Subgroup analysis

Figure 4 provides the subgroup analysis including all HR with 95% CI. The subgroup analysis revealed a comparable performance of the CONFIRM score in women (HR 2.8 with 95% CI 2.45 and 3.21) and men (HR 2.83 with 95% CI 2.46 and 3.25) and in asymptomatic (HR 3.15 with 95% CI 2.62 and 3.80) and symptomatic patients (HR 2.99 with 95% CI 2.55 and 3.52). Moreover, the score seems to be particularly useful in older patients and patients with a higher NCEP ATP III score.

Figure 4.

Predictive value of the CONFIRM score in subgroups. Hazard ratios are provided for comparison of the 25th and 75th percentile and presented with 95% CIs.

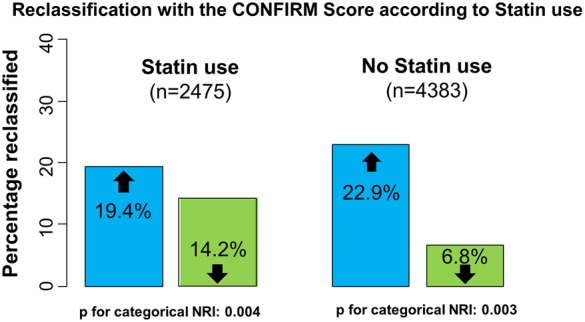

Categorical NRI and IDI revealed a significant risk reclassification in diabetic patients (P < 0.001 for both), patients with hypertension (P < 0.01 for categorical NRI and P = 0.04 for IDI), patients with hyperlipoproteinemia (P < 0.01 for both), active smokers (P < 0.01 for both), and patients with a positive family history (P < 0.001 for both) as well as for patients on aspirin (P < 0.01 for categorical NRI and P = 0.01 for IDI) and statin treatment (P < 0.01 for categorical NRI and P = 0.04 for IDI).

In patients on statin treatment at baseline, 19.4% of patients could be upgraded to a higher risk group and 14.2% of patients were downgraded to a lower risk group with the use of the CONFIRM score, while 22.9% of patients and 6.8% without statin treatment at baseline could be upgraded or downgraded, respectively (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Reclassification comparing the CONFIRM and National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) score (NCEP ATP III score) in patients with and without statin treatment at baseline. Light blue and light green shading indicate upward and downward risk reclassification with the CONFIRM score, respectively. Information about statin treatment at baseline was available in 6858 patients.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that the CONFIRM score, which incorporates the clinical risk profile and CCTA findings, significantly correlates with all-cause mortality in a large cohort of patients with 5-year follow-up. Furthermore, the results prove that CCTA findings can add incremental prognostic value to patient risk stratification in comparison to clinical risk scores alone. Similar findings have been published before, but were obtained from smaller single-centre investigations.5,22,23 To our knowledge, this analysis is the first to compare a risk score based upon clinical risk factors and CCTA findings to traditional clinical risk scores in such a large cohort of patients with 5-year follow-up.

The unique strength of CCTA compared with other non-invasive imaging modalities is the provided anatomical information, which allows for the detection of atherosclerosis at earlier disease stages.9 Thus, it is not surprising that patients without any atherosclerotic changes in CCTA have a very favourable prognosis.5,7 In addition, a high negative predictive value for the exclusion of CAD has been reported for CCTA.2 Consequently, CCTA has been recurrently proposed as a gatekeeper for invasive coronary angiography to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures.8,24,25

The study reveals that approximately one-third of the patients could be reclassified to a different risk group when the CONFIRM score is used instead of the NCEP ATP III score, which has been identified as the best traditional risk score in the current very large patient population. The subgroup analysis indicates that the predictive value of the CONFIRM score is higher in older patients and patients with a higher overall clinical risk assessed by the NCEP ATP III score.

The results of the present study facilitate the hypothesis of an additive predictive value of CCTA for a more customized patient management, e.g. more rigorous medical treatment of cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes or arterial hypertension in high-risk patients. So far, evidence in this field is rare. The FACTOR 64 trial investigated benefits of a more aggressive therapy regimen in patients with diabetes based upon CCTA findings in 900 patients in a prospective fashion.26 Within 4 years, the combined primary endpoint of all-cause mortality, non-fatal MI, and unstable angina occurred in 28 patients in the CCTA group and in 34 patients in the control group (P = 0.38) in their study. However, at baseline >70% of patients in both groups were already on statin therapy which is a limitation for CCTA guided more aggressive medical therapy regimens. The SCOT-HEART trial randomized 4146 patients with angina suspected to be caused by CAD to a standard care or a standard care plus CCTA group. After 1.7 years, the occurrence of myocardial infarction was 38% lower in the CCTA group (26 vs. 42 patients). Findings barely missed statistical significance (P = 0.053).27 However, in a substudy from the SCOT-HEART trial recently published by Williams et al. the occurrence of fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction was significantly lower (17 vs. 34, P = 0.02) when early events occurring within the first 50 days after randomization were excluded.28 Those findings underline the ongoing necessity to effectively translate the predictive power of CCTA in a benefit for patients in daily clinical practise.

Although there is strong evidence that statin treatment can reduce the occurrence of adverse cardiovascular events and mortality in patients with proven CAD, statin treatment is not incorporated into major clinical risk scores such as the NCEP ATP III score, Framingham score, or Morise score which were used in our study.29,30 However, our results prove that the additive predictive value of CCTA is maintained in both patients with and without statin treatments. Our subgroup analysis of patients on statin treatment further indicates that CCTA's usefulness is not limited to the identification of patients, who benefit from statin treatment, but also might be useful to identify patients, who do not benefit from statin treatment. Those findings are in line with the above cited substudy from the SCOT-HEART trial by Williams et al.28 Their analysis revealed that preventive treatment was significantly more often initiated in the CCTA group (293 vs. 84, P < 0.001), but was also significantly more often cancelled in the CCTA group (77 vs. 8, P < 0.001).

The present study has several strengths but also a few limitations. Strengths are the large number of patients analysed, the multicentre design, the long follow-up period with >75 000 cumulative patient years, the analysis of a large variety of subgroups and the use of a hard endpoint. Most limitations are based on the observational design of the CONFIRM registry. Information about lifestyle changes, medical therapy, or myocardial revascularization procedures based upon CCTA findings is very limited and might have had significant effects on patient outcome.

Conclusion

The present patient population undergoing CCTA for suspected CAD is the largest population with a 5-year follow-up allowing a robust analysis of predictors for all-cause mortality. The CONFIRM score, which incorporates the clinical risk profile as well as CCTA findings, confirms that CCTA carries incremental prognostic information over established clinical risk scores. In addition, the CONFIRM score permits effective reclassification of patients to clinical risk categories. The improvement in risk prediction has been established for a variety of different patient subgroups and is independent of aspirin and statin treatment at baseline.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Heart Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number 1R01HL115150. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported by Leading Foreign Research Institute Recruitment Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (MSIP) (2012027176). This study was also funded, in part, by a generous gift from the Dalio Institute of Cardiovascular Imaging (New York, NY) and the Michael Wolk Foundation (New York, NY).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all investigators at the participating sites for their effort to collect data for the CONFIRM registry.

References

- 1. Achenbach S, Marwan M, Ropers D, Schepis T, Pflederer T, Anders K et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography with a consistent dose below 1 mSv using prospectively electrocardiogram-triggered high-pitch spiral acquisition. Eur Heart J 2010;31:340–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Budoff MJ, Dowe D, Jollis JG, Gitter M, Sutherland J, Halamert E et al. Diagnostic performance of 64-multidetector row coronary computed tomographic angiography for evaluation of coronary artery stenosis in individuals without known coronary artery disease: results from the prospective multicenter ACCURACY (Assessment by Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography of Individuals Undergoing Invasive Coronary Angiography) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1724–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Deseive S, Pugliese F, Meave A, Alexanderson E, Martinoff S, Hadamitzky M et al. Image quality and radiation dose of a prospectively electrocardiography-triggered high-pitch data acquisition strategy for coronary CT angiography: the multicenter, randomized PROTECTION IV study. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2015;9:278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hadamitzky M, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Berman D, Budoff M, Cademartiri F et al. Optimized prognostic score for coronary computed tomographic angiography: results from the CONFIRM registry (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicenter Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hadamitzky M, Taubert S, Deseive S, Byrne RA, Martinoff S, Schomig A et al. Prognostic value of coronary computed tomography angiography during 5 years of follow-up in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2013;34:3277–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leipsic J, Taylor CM, Gransar H, Shaw LJ, Ahmadi A, Thompson A et al. Sex-based prognostic implications of nonobstructive coronary artery disease: results from the international multicenter CONFIRM study. Radiology 2014;273:393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ et al. Age- and sex-related differences in all-cause mortality risk based on coronary computed tomography angiography findings results from the International Multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: An International Multicenter Registry) of 23,854 patients without known coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:849–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaw LJ, Hausleiter J, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Berman DS, Budoff MJ et al. Coronary computed tomographic angiography as a gatekeeper to invasive diagnostic and surgical procedures: results from the multicenter CONFIRM (Coronary CT Angiography Evaluation for Clinical Outcomes: an International Multicenter) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:2103–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erbel R. The dawn of a new era – non-invasive coronary imaging. Herz 1996;21:75–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Graaf MA, Broersen A, Ahmed W, Kitslaar PH, Dijkstra J, Kroft LJ et al. Feasibility of an automated quantitative computed tomography angiography-derived risk score for risk stratification of patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2014;113:1947–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Min JK, Dunning A, Lin FY, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah MH, Berman DS et al. Rationale and design of the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicenter) Registry. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2011;5:84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). J Am Med Assoc 2001;285:2486–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morise AP, Jalisi F. Evaluation of pretest and exercise test scores to assess all-cause mortality in unselected patients presenting for exercise testing with symptoms of suspected coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:842–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wilson PW, D'Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998;97:1837–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abbara S, Arbab-Zadeh A, Callister TQ, Desai MY, Mamuya W, Thomson L et al. SCCT guidelines for performance of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2009;3:190–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hendel RC, Patel MR, Kramer CM, Poon M, Hendel RC, Carr JC et al. ACCF/ACR/SCCT/SCMR/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SIR 2006 appropriateness criteria for cardiac computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Quality Strategic Directions Committee Appropriateness Criteria Working Group, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, North American Society for Cardiac Imaging, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Interventional Radiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:1475–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Taylor AJ, Cerqueira M, Hodgson JM, Mark D, Min J, O'Gara P et al. ACCF/SCCT/ACR/AHA/ASE/ASNC/NASCI/SCAI/SCMR 2010 appropriate use criteria for cardiac computed tomography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:1864–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation 1975;51(4 Suppl):5–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Araujo Goncalves P, Garcia-Garcia HM, Dores H, Carvalho MS, Jeronimo Sousa P, Marques H et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography-adapted Leaman score as a tool to noninvasively quantify total coronary atherosclerotic burden. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;29:1575–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 1996;15:361–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Team RDC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dougoud S, Fuchs TA, Stehli J, Clerc OF, Buechel RR, Herzog BA et al. Prognostic value of coronary CT angiography on long-term follow-up of 6.9 years. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;30:969–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ostrom MP, Gopal A, Ahmadi N, Nasir K, Yang E, Kakadiaris I et al. Mortality incidence and the severity of coronary atherosclerosis assessed by computed tomography angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:1335–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chow BJ, Abraham A, Wells GA, Chen L, Ruddy TD, Yam Y et al. Diagnostic accuracy and impact of computed tomographic coronary angiography on utilization of invasive coronary angiography. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karlsberg RP, Budoff MJ, Thomson LE, Friedman JD, Berman DS. Reduction in downstream test utilization following introduction of coronary computed tomography in a cardiology practice. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2010;26:359–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Lima JA, Rosen BD, May HT, Knight S et al. Effect of screening for coronary artery disease using CT angiography on mortality and cardiac events in high-risk patients with diabetes: the FACTOR-64 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:2234–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. SCOT-HEART Investigators. CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet 2015;385:2383–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Williams MC, Hunter A, Shah AS, Assi V, Lewis S, Smith J et al. Use of coronary computed tomographic angiography to guide management of patients with coronary disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1759–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kostis WJ, Cheng JQ, Dobrzynski JM, Cabrera J, Kostis JB. Meta-analysis of statin effects in women versus men. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:572–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chow BJ, Small G, Yam Y, Chen L, McPherson R, Achenbach S et al. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of statin and aspirin therapy in individuals with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: results from the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicenter registry) registry. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2015;35:981–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]