Abstract

Background: Hyponatremia and hypernatremia are associated with death in the general population and those with chronic kidney disease (CKD). We studied the associations between dysnatremias, all-cause mortality and causes of death in a large cohort of Stage 3 and 4 CKD patients.

Methods: We included 45 333 patients with Stage 3 and 4 CKDs followed in a large healthcare system. Associations between hyponatremia (<136 mmol/L) and hypernatremia (>145), and all-cause mortality and causes of death (cardiovascular, malignancy related and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy related) were studied using Cox proportional hazards and competing risk models.

Results: Dysnatremias were found in 9.2% of the study population. In separate multivariable Cox proportional hazards models using baseline serum sodium levels and time-dependent repeated measures, both hyponatremia and hypernatremia were associated with all-cause mortality. In the competing risk analyses, hyponatremia was significantly associated with increased risk for various cause-specific mortality categories [cardiovascular (hazard ratio, HR 1.16, 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.04, 1.30), malignancy related (HR 1.48, 95% CI: 1.33, 1.65) and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy deaths (HR 1.25, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.39)], while hypernatremia was significantly associated with higher non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy mortality only (HR 1.36, 95% CI: 1.08, 1.72).

Conclusions: In those with CKD, hyponatremia was associated with all-cause mortality, cardiovascular, malignancy and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths. Hypernatremia was associated with all-cause and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of differences in cause-specific death among CKD patients with hyponatremia and hypernatremia.

Keywords: mortality and chronic kidney disease, sodium

INTRODUCTION

Serum sodium is maintained at a relatively constant level in our body, with the kidneys playing a pivotal role [1, 2]. Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) may be more susceptible to the development of abnormalities of serum sodium level by virtue of their diminished ability to maintain water homeostasis [3, 4]. Hypo- and hypernatremia are common electrolyte abnormalities leading to a spectrum of clinical symptoms [1, 5]. Serum sodium abnormalities are associated with increased mortality, morbidity and length of hospital stay among patients with various disease states [6–10]. Furthermore, several studies have reported other non-fatal but serious complications such as hyponatremic encephalopathy in postoperative and other clinical conditions [11–13].

Hyponatremia is associated with higher risk for mortality in maintenance dialysis patients [14–17]. Few studies have examined the impact of hyponatremia on outcomes in CKD patients not on dialysis [18, 19]. Among ambulatory US Veterans with CKD, hyponatremia and hypernatremia were associated with mortality, independent of congestive heart failure (CHF) and liver disease [19]. Increased all-cause mortality was also found among non-dialysis CKD patients with hyponatremia followed in CKD clinics in the UK [20]. Among ambulatory CKD patients followed in nephrology clinics, patients with hyponatremia were at a higher risk for end-stage renal disease, and there was a higher risk for death in those with hyponatremia and hypernatremia [18]. However, reasons for these higher risks of death in CKD have not been studied among a general ambulatory non-dialysis-dependent patient population. To address this, we investigated the association of serum sodium levels with both all-cause and cause-specific deaths in a diverse population of ambulatory Stage 3 and 4 CKD patients [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 15–59 mL/min/1.73 m2] followed in a large healthcare system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We conducted an analysis using a preexisting Electronic Health Record (EHR)-based CKD registry. The development and validation of the EHR-based CKD registry at Cleveland Clinic have been described in detail elsewhere [21, 22].

Study population

Patients who met the following criteria from 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2012 were included in the study population: (i) had at least one face-to-face outpatient encounter with a Cleveland Clinic healthcare provider, (ii) had two or more eGFR values <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 more than 90 days apart, (iii) were residents of the state of Ohio and (iv) had a serum sodium and glucose measured on the date of the second eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Definitions and outcome measures

Renal function

We applied the CKD-EPI equation to patients in our health system who had at least two outpatient serum creatinine levels between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2012 to calculate eGFR [23]. All creatinine measurements were performed by the modified kinetic Jaffe reaction, using a Hitachi D 2400 Modular Chemistry Analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in our laboratory. CKD was defined according to current guidelines as follows: Stage 3 CKD (eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) and Stage 4 CKD (eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2). We further categorized Stage 3 into CKD Stage 3a (eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) and Stage 3b (eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Serum sodium and glucose

Only outpatient serum sodium laboratory measures obtained with a same reference range were included in this analysis. We calculated corrected serum sodium levels for patients with glucose >200 mg/dL using the formula: corrected serum sodium = measured serum sodium + 1.6 (serum glucose − 100)/100. Hyponatremia was defined as <136 mmol/L. Hypernatremia was defined as >145 mmol/L [18]. Serum sodium levels measured on the day of the second eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 at least 90 days after the first eGFR, as described, were used for the baseline serum sodium analysis. For our time-dependent repeated measures analysis, we included the baseline serum sodium value as well as the first serum sodium value measured each month during the study follow-up. For each monthly serum sodium, the concomitant glucose value was used for adjustment. We used carry-forward values to fill in data for months where the serum sodium data were not available.

Outcomes

Mortality was ascertained from the EHR and linkage of the CKD registry with the Ohio Department of Health mortality files to obtain cause-specific mortality details. The underlying cause of death was coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10). We grouped the underlying causes of death according to the National Center for Health Statistics for each coding system, except for some changes as outlined below. We classified deaths into three major categories: (i) cardiovascular deaths, (ii) malignancy-related deaths and (iii) non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths. We defined cardiovascular deaths as deaths due to diseases of the heart, essential hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, atherosclerosis or other diseases of the circulatory system (ICD-10 codes I00–I78). We also categorized the cardiovascular deaths into the following clinically meaningful subcategories: ischemic heart disease (I20–I25), heart failure (I50), cerebrovascular diseases (I60s) and all other cardiovascular diseases (include all others from I00 to I78, except for I20–I25, I50 and I60). Patients were followed from their date of inclusion in the registry (date of second eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) until 31 December 2012.

Statistical analyses

CKD patients with measured outpatient serum sodium values adjusted for glucose at the time of second eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were further classified into low (<136 mmol/L), normal (136–145 mmol/L) and high (>145 mmol/L) serum sodium as described above. Associations between demographic and baseline characteristics and baseline serum sodium levels were assessed using χ2 and ANOVA tests or the Kruskal–Wallis test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. We fitted a logistic regression analysis to evaluate the factors associated with hyponatremia compared with normal serum sodium levels at the time of second eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Covariates were based on information known prior to second eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and chosen a priori based on factors previously shown or thought to be related to serum sodium and mortality. These include age groups, gender, race, body mass index (BMI) group, eGFR, diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, malignancy, CHF, liver disease, smoking and diuretic use. Factors associated with hypernatremia were not studied due to the small sample size.

To evaluate whether overall survival was associated with serum sodium levels, we used the Kaplan–Meier plots and log-rank tests with the date of second eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 and sodium measurement as the time of origin. We used a Poisson model to estimate age-adjusted death rates per 1000 years of follow-up across the levels of baseline serum sodium. We fitted Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the relationship between baseline serum sodium and all-cause mortality. To incorporate serum sodium results obtained after inception, we fitted a Cox proportional hazards model of all-cause mortality with time-dependent repeated measures of serum sodium. We also used Fine and Gray's extension of the Cox regression that models the cumulative incidence to fit competing risk regression models and to evaluate the association between baseline serum sodium levels and each cause-specific mortality (malignancy, cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy). In each of these models, we adjusted for the covariates mentioned above and following additional variables: coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin receptor blocker use, beta blocker use, albumin, hemoglobin, serum bicarbonate and hyperlipidemia. We used splines to relax linearity assumptions for continuous variables included in the models.

We tested two-way interactions between low serum sodium and the following covariates: age, gender, race, diabetes, CHF and eGFR in the adjusted Cox proportional hazards model of all-cause mortality with time-dependent repeated measures of serum sodium. We also examined the relationship between time-dependent continuous serum sodium and all-cause mortality using restricted cubic splines with knots at percentiles 5, 25, 50, 75 and 95. These splines allowed us to model a flexible non-linear relationship between sodium and mortality. We plotted the resulting log hazard from this model versus continuous serum sodium.

We had the following missing data: smoking 9%, BMI 3%, albumin 14% and hemoglobin 13%. We used multiple imputations [SAS proc multiple imputation (MI)] with the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method and a single chain to impute five datasets with complete data. All logistic and Cox models were performed on each of the five imputed datasets, and parameter estimates were combined using SAS MIanalyze. To evaluate the effect of using multiple imputations, we fitted the logistic, Cox and competing risks models on complete cases only. We also performed an additional sensitivity analysis on mortality by excluding patients with baseline malignancy.

All data analyses were conducted using Unix SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R 3.0.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The CKD registry and this study were approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 45 333 Stage 3 and 4 CKD patients who had serum sodium and glucose levels measured on the date of second eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 were included in the analysis (Supplementary data, Figure S1). Mean age of the study population was 72 ± 11.9 years with 55% being females and 14% African Americans. Using the baseline serum sodium levels, hyponatremia and hypernatremia were noted among 8 and 1.2% of the study population, respectively. While considering the serum sodium results obtained during follow-up, hyponatremia and hypernatremia were noted among 9 and 0.9% of all laboratory measurements. Among patients with follow-up sodium values, 27% sustained at least one episode of hyponatremia, while 6% experienced at least one episode of hypernatremia. Demographic characteristics and comorbid conditions were significantly different among patients with high or low baseline serum sodium levels compared with normal serum sodium (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study cohort based on serum sodium levels at baseline

| Factor | Total (N = 45 333) | Normal (136–145 mmol/L) (N = 41 175) | Hyponatremia (<136 mmol/L) (N = 3626) | Hypernatremia (>145 mmol/L) (N = 532) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 71.9 ± 11.9 | 71.9 ± 11.9 | 71.9 ± 12.9 | 73.3 ± 11.6 |

| Male gender | 44.6 | 44.8 | 41.9 | 46.1 |

| African American | 14.3 | 14.3 | 12.7 | 27.4 |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 83.7 | 84.0 | 81.5 | 76.3 |

| Yes | 7.2 | 7.0 | 9.9 | 9.0 |

| Missing | 9.1 | 9.0 | 8.6 | 14.7 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 48.0 ± 10.2 | 48.2 ± 10.1 | 46.0 ± 11.1 | 44.5 ± 11.9 |

| CKD stages | ||||

| Stage 3a (eGFR 45–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 68.6 | 69.5 | 61.0 | 55.1 |

| Stage 3b (eGFR 30–44 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 24.0 | 23.5 | 28.2 | 29.7 |

| Stage 4 (eGFR 15–29 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 7.4 | 7.0 | 10.8 | 15.2 |

| BMI kg/m2* | 29.4 ± 6.5 | 29.5 ± 6.5 | 28.2 ± 6.7 | 29.3 ± 7.1 |

| BMI group | ||||

| <18.5 kg/m2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 | 23.0 | 22.2 | 31.5 | 25.4 |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 35.0 | 35.3 | 32.8 | 31.4 |

| 30+ kg/m2 | 38.0 | 38.6 | 30.4 | 36.7 |

| Missing | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 4.5 |

| Diabetes | 25.0 | 25.1 | 24.0 | 25.6 |

| Hypertension | 91.0 | 91.1 | 89.4 | 90.4 |

| Coronary artery disease | 22.6 | 22.6 | 21.8 | 22.2 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 9.8 | 9.8 | 10.3 | 11.3 |

| CHF | 8.8 | 8.5 | 12.8 | 9.2 |

| Malignancy | 26.3 | 26.1 | 29.0 | 24.2 |

| Liver disease | 6.1 | 5.5 | 12.6 | 3.0 |

| ACEI/ARB | 66.2 | 65.8 | 70.8 | 67.9 |

| Beta blocker | 57.7 | 57.3 | 62.4 | 58.8 |

| Statin | 60.1 | 60.9 | 52.1 | 59.0 |

| Albumin, g/dL* | 4.1 ± 0.42 | 4.2 ± 0.40 | 4.0 ± 0.56 | 4.1 ± 0.51 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL* | 12.8 ± 1.8 | 12.9 ± 1.8 | 12.1 ± 1.9 | 12.6 ± 1.8 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mmol/L | 25.8 ± 3.2 | 26.0 ± 3.1 | 24.5 ± 3.7 | 26.0 ± 4.1 |

| Serum bilirubin, mg/dL* | 0.40 (0.30, 0.60) | 0.40 (0.30, 0.60) | 0.50 (0.30, 0.70) | 0.40 (0.30, 0.60) |

| AST, µ/L* | 23.0 (19.0, 28.0) | 23.0 (19.0, 28.0) | 24.0 (19.0, 32.0) | 22.0 (18.0, 27.0) |

| ALT, µ/L* | 17.0 (13.0, 24.0) | 17.0 (13.0, 23.0) | 17.0 (13.0, 26.0) | 17.0 (13.0, 22.0) |

ACEI/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase.

*Data not available for all subjects. Missing values: BMI 1242, albumin 6447, hemoglobin 5904, serum bilirubin 6457, AST 6089 and ALT 3698.

Values are presented as mean ± SD, median (P25, P75) or column %.

All variables significantly different (P < 0.05) across sodium levels, except for diabetes, coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease.

Factors associated with hyponatremia

In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, the following variables were associated with higher odds of having hyponatremia compared with those with normal serum sodium levels: younger age, female gender, lower eGFR, malignancy, liver disease, CHF, diuretic use and smoking (Table 2).

Table 2.

Factors associated with hyponatremia in CKD

| Variable | Adjusted OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| <60 | Ref. |

| 60–69 | 0.79 (0.70, 0.88) |

| 70–79 | 0.75 (0.67, 0.83) |

| >80 | 0.89 (0.79, 0.99) |

| Male sex | 0.87 (0.81, 0.94) |

| African-American race | 0.78 (0.70, 0.87) |

| eGFR (per 5 mL/min lower) | 1.10 (1.08, 1.11) |

| Diabetes | 0.99 (0.91, 1.08) |

| Hypertension | 0.80 (0.71, 0.90) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.01 (0.90, 1.14) |

| Malignancy | 1.23 (1.14, 1.33) |

| Liver disease | 2.28 (2.04, 2.55) |

| CHF | 1.41 (1.26, 1.57) |

| Diuretic use | 1.58 (1.45, 1.72) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |

| <18.5 | 1.18 (0.92, 1.51) |

| 18.5–24.9 | Ref. |

| 25–29.9 | 0.69 (0.63, 0.75) |

| ≥30 | 0.55 (0.50, 0.60) |

| Smoking | 1.38 (1.23, 1.56) |

aAdjusted for year of entry into registry and all other variables in the table. Odds ratios (ORs) and CIs shown were obtained using MI analyzed from five imputed datasets.

Serum sodium levels and all-cause mortality

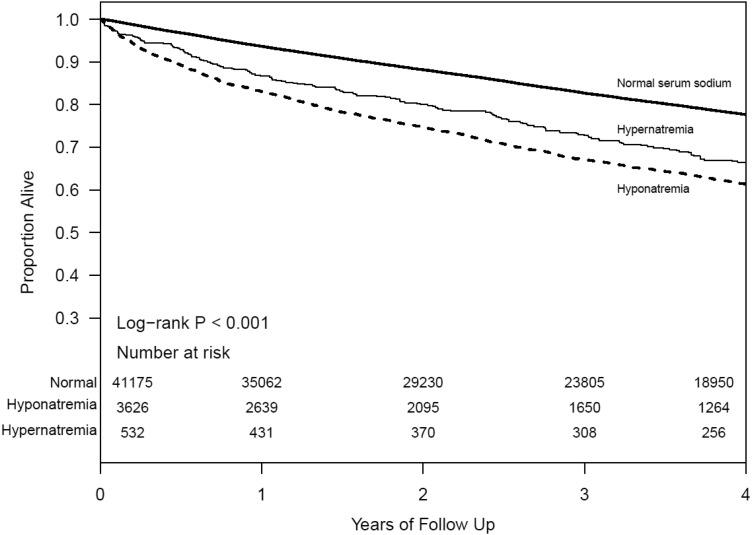

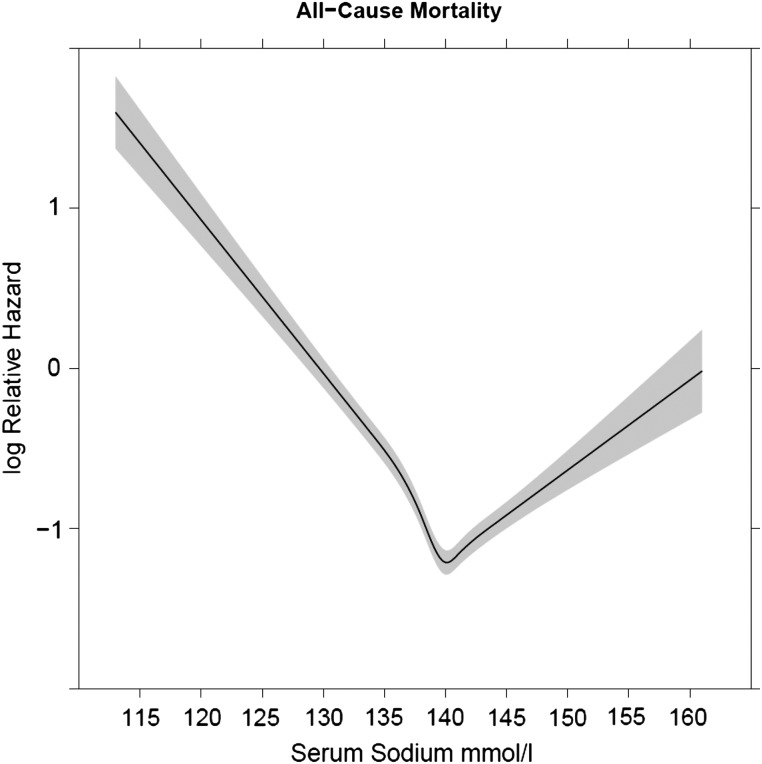

Among our study population, 11 715 died (26%) during a median follow-up of 3.6 years. Both the Kaplan–Meier (Figure 1) and Cox proportional hazards analyses showed significantly higher all-cause mortality among those with low and high baseline serum sodium levels. After adjusting for relevant confounding variables (using baseline serum sodium levels), both hyponatremia [hazard ratio (HR) 1.39, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.32–1.48] and hypernatremia (HR 1.31, 95% CI: 1.14–1.51) were associated with all-cause mortality. In the multivariable models with time-dependent repeated measures of serum sodium, both hyponatremia (HR 2.24, 95% CI: 2.14–2.35) and hypernatremia (HR 1.66, 95% CI: 1.44–1.91) were associated with significantly higher risk for all-cause mortality. Figure 2 shows the relationship between serum sodium as a continuous measure and the log hazard of all-cause deaths.

FIGURE 1.

Survival of those with hyponatremia and hypernatremia in CKD.

FIGURE 2.

Associations of serum sodium (as a continuous measure) with all-cause mortality in CKD.

Serum sodium and reasons for death

Supplementary data, Table S1 shows the main causes of death among those with normal serum sodium, hyponatremia and hypernatremia at baseline. Supplementary data, Table S2 details the age-adjusted mortality rates (all-cause and other cause-specific deaths) based on baseline serum sodium levels. Hyponatremia was also significantly associated with increased risk for each cause-specific mortality category (Table 3), while hypernatremia was significantly associated with higher non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy mortality.

Table 3.

Associations between serum sodium at baseline and various causes of death in CKD (using competing risk models)

| Hyponatremia sub-hazard ratio (95% CI) | Hypernatremia sub-hazard ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Malignancy-related deaths | 1.48 (1.33, 1.65) | 1.14 (0.84, 1.56) |

| Cardiovascular deaths | 1.16 (1.04, 1.30) | 1.24 (0.97, 1.58) |

| Non-cardiovascular/ non-malignancy-related deaths | 1.25 (1.13, 1.39) | 1.36 (1.08, 1.72) |

Data were adjusted for age, gender, African American, smoking, BMI group, eGFR, diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, CHF, hyperlipidemia, malignancy, angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin receptor blocker, beta blocker, diuretics, albumin, hemoglobin, serum bicarbonate and liver disease.

Hazard ratios and CIs shown were obtained using MI analyze from five imputed datasets.

Effect modification by age, CKD stage and CHF

We found significant two-way interactions between hyponatremia and age, eGFR and gender on all-cause mortality. These interactions indicated that while significant at all levels, the increased mortality hazard associated with hyponatremia was stronger among younger ages (P < 0.001), at higher eGFR levels (P < 0.001) and among males (P < 0.001) (see Supplementary data, Table S3).

Sensitivity analyses

Excluding those with malignancy and complete case analysis

Supplementary data, Tables S4 and S5 show the associations between hyponatremia and hypernatremia by excluding those with malignancy at baseline and by including only patients with complete data. Associations between hyponatremia and various causes of death were qualitatively similar to the primary analysis except for malignancy-related deaths.

DISCUSSION

In this cohort of ambulatory patients with Stage 3 and 4 CKDs, dysnatremias were noted in ∼9% of the study population. Several demographic and clinical factors were associated with hyponatremia in CKD. We found that hyponatremia was associated with higher risk for all-cause and various causes of death, even after adjusting for various confounding variables. Similarly, we found an association between hypernatremia and higher risk for all-cause and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths in the primary analysis. Associations between hyponatremia and mortality were stronger in those who were younger and with earlier stages of kidney disease.

The prevalence of hyponatremia at hospital admission ranges from 5 to 35% [2, 24]. Among studies that included an ambulatory CKD population, prevalence ranges from 6 to 13.5% [18, 19, 25]. The proportion of patients with hyponatremia was similar to other previous reports, and we had similar findings in terms of demographic characteristics associated with hyponatremia and adverse outcomes such as increased all-cause mortality with sodium disorders. Importantly, we add to the literature regarding cause-specific mortality for sodium abnormalities in CKD, which has not been reported before.

Risk factors for hyponatremia noted in other studies include advanced age, male gender and low body weight. Hyponatremia is also associated with many different disease states such as CHF, liver disease and pneumonia. Most of our findings were concordant with these previous studies: hyponatremia was more frequently observed in patients with lower eGFR, malignancy, liver disease, CHF and diuretic use, while the following variables were associated with lower odds of having low serum sodium levels: being overweight and hypertension. Unlike other reports in the literature, we found females to be at higher risk of hyponatremia when adjusting for other comorbidities. We noted lower odds of hyponatremia in older adults, which could be due to the younger sicker patients followed in the healthcare system. The mean age of patients with hyponatremia was lower than those who had normal serum sodium level in a Veterans Affairs study cohort [19]. Lower levels of kidney function are associated with higher odds of hyponatremia, pointing out the diminished ability to maintain water homeostasis in CKD.

Studies have reported an association between hyponatremia and mortality across many diverse conditions (e.g. pneumonia, heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, cirrhosis, pulmonary embolism and cancer) [26, 27]. Hyponatremia was associated with an increased risk of overall mortality (relative risk: 2.60, 95% CI: 2.31, 2.93) in a meta-analysis [10]. Our baseline sodium analysis and time-dependent analyses confirm these findings. In the competing risk models, we also noted that hyponatremia was associated with cardiovascular, malignancy-related and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths, suggesting that sodium disorders have effects on multiple systems in humans rather than cardiovascular health alone.

Mild hyponatremia and hypernatremia are both associated with increased total mortality and cardiovascular events in older men, and the known cardiovascular risk factors did not explain the excess risk of all-cause mortality [28]. Hyponatremia is associated with cognitive deficits, bone disease and falls [29–31]. Our findings of higher risk for non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths could be attributed to these non-traditional mediation effects of hyponatremia (e.g. hyponatremia leading to falls and then subsequent non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths). Due to the nature of the study cohort, we lacked details of cognitive impairment, falls and fractures, etc. to further explore this. A relationship between hyponatremia and brain edema has been reported, and whether this contributes to the mortality burden warrants further studies [32]. Another possible mechanism for the increased cardiovascular mortality associated with hyponatremia independent of underlying disease may be hyponatremia-induced oxidative stress and inflammation [33]. Even though hyponatremia was associated with malignancy-related deaths, such an association was not observed in those without preexisting malignancy (Supplementary data, Table S4). It is important to note that despite numerous studies demonstrating higher mortality risks with sodium abnormalities, clinical trials examining whether correcting sodium levels will improve outcomes are lacking [27]. Furthermore, the higher risk of death among older adults and in those with higher GFR categories could be attributed to the fact that aging and decline in kidney function per se override the detrimental effects of other factors in CKD.

Our study has many strengths including a large diverse ambulatory population with Stage 3 and 4 CKDs, availability of several confounding variables and the use of time-dependent repeated measures analyses to account for changes in serum sodium over time. Importantly, we have examined the reasons for death in those with different levels of serum sodium in this population through our linkage of cause-specific mortality data. Although we had availability of multiple relevant variables, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Despite these strengths, there are limitations to our study. We included several variables that could affect serum sodium levels and are related to mortality; however, we lacked details about severity of the comorbidities, and other factors such as urine osmolality and other details to categorize the reasons for hyponatremia further. Also, our patients have been followed in a healthcare system, and hence these data might not be applicable to community-dwelling adults with CKD. It is important to point out that the associations between hypernatremia and outcomes were not significant in the sensitivity analyses, which could be attributed to the smaller number of events. We obtained cause-specific death data from the State of Ohio Department of Health mortality files, which provides data to the National Death Index. These data have been used by several studies in the past and are considered to be reliable. We have also confirmed the reliability of death certificate-derived data using chart review [34, 35]. Previous reports indicated higher infections among those with hyponatremia in the dialysis population. But, we could not examine this further due to the lack of infection-related details, a topic of interest for future investigations [36].

In summary, hyponatremia and hypernatremia were associated with all-cause mortality among patients with Stage 3 and 4 CKDs in our study population. Additionally, we found associations of increased cause-specific mortality not just with cardiovascular deaths but also with malignancy, and non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths among those with hyponatremia compared with those without. Hypernatremia was associated with non-cardiovascular/non-malignancy-related deaths. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of differences in cause-specific death among CKD patients with sodium abnormalities along with determining whether correcting sodium abnormalities will lower mortality.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Mr Welf Saupe, Ms Vicky Konig and Mr John Sharp of Cleveland Clinic who helped in data extraction during the development of the registry. S.D.N. is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01DK101500), J.V.N. is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (DK094112) and S.E.J. is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K23DK091363). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The creation of the CCF CKD registry was funded by an unrestricted grant from Amgen, Inc. to the Cleveland Clinic Department of Nephrology and Hypertension Research and Education Fund.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared. The results presented in this paper have not been published previously in whole or part.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Hyponatremia. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1581–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Incidence and prevalence of hyponatremia. Am J Med 2006; 119: S30–S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. The challenge of hyponatremia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012; 23: 1140–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Combs S, Berl T. Dysnatremias in patients with kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2014; 63: 294–303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Hypernatremia. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 1493–1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Darmon M, Timsit JF, Francais A. et al. Association between hypernatraemia acquired in the ICU and mortality: a cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25: 2510–2515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goldberg A, Hammerman H, Petcherski S. et al. Prognostic importance of hyponatremia in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Med 2004; 117: 242–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuramatsu JB, Bobinger T, Volbers B. et al. Hyponatremia is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 2014; 45: 1285–1291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schou M, Valeur N, Torp-Pedersen C. et al. Plasma sodium and mortality risk in patients with myocardial infarction and a low LVEF. Eur J Clin Invest 2011; 41: 1237–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Corona G, Giuliani C, Parenti G. et al. Moderate hyponatremia is associated with increased risk of mortality: evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2013; 8: e80451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ayus JC, Achinger SG, Arieff A. Brain cell volume regulation in hyponatremia: role of sex, age, vasopressin, and hypoxia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008; 295: F619–F624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ayus JC, Varon J, Arieff AI. Hyponatremia, cerebral edema, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema in marathon runners. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132: 711–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ayus JC, Wheeler JM, Arieff AI. Postoperative hyponatremic encephalopathy in menstruant women. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117: 891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nigwekar SU, Wenger J, Thadhani R. et al. Hyponatremia, mineral metabolism, and mortality in incident maintenance hemodialysis patients: a cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 62: 755–762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chang TI, Kim YL, Kim H. et al. Hyponatremia as a predictor of mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. PLoS One 2014; 9: e111373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rhee CM, Ravel VA, Ayus JC. et al. Pre-dialysis serum sodium and mortality in a national incident hemodialysis cohort. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016; 31: 992--1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waikar SS, Curhan GC, Brunelli SM. Mortality associated with low serum sodium concentration in maintenance hemodialysis. Am J Med 2011; 124: 77–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Han SW, Tilea A, Gillespie BW. et al. Serum sodium levels and patient outcomes in an ambulatory clinic-based chronic kidney disease cohort. Am J Nephrol 2015; 41: 200–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kovesdy CP, Lott EH, Lu JL. et al. Hyponatremia, hypernatremia, and mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease with and without congestive heart failure. Circulation 2012; 125: 677–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chiu DY, Kalra PA, Sinha S. et al. Association of serum sodium levels with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease: Results from a prospective observational study. Nephrology (Carlton) 2015; doi:10.1111/nep.12634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Navaneethan SD, Jolly SE, Schold JD. et al. Development and validation of an electronic health record-based chronic kidney disease registry. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 40–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Navaneethan SD, Jolly SE, Sharp J. et al. Electronic health records: a new tool to combat chronic kidney disease? Clin Nephrol 2013; 79: 175–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 604–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waikar SS, Mount DB, Curhan GC. Mortality after hospitalization with mild, moderate, and severe hyponatremia. Am J Med 2009; 122: 857–865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liamis G, Rodenburg EM, Hofman A. et al. Electrolyte disorders in community subjects: prevalence and risk factors. Am J Med 2013; 126: 256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abu Zeinah GF, Al-Kindi SG, Hassan AA. et al. Hyponatraemia in cancer: association with type of cancer and mortality. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015; 24: 224–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoorn EJ, Zietse R. Hyponatremia and mortality: moving beyond associations. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 62: 139–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L. et al. Mild hyponatremia, hypernatremia and incident cardiovascular disease and mortality in older men: A population-based cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016; 26: 12–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Renneboog B, Musch W, Vandemergel X. et al. Mild chronic hyponatremia is associated with falls, unsteadiness, and attention deficits. Am J Med 2006; 119: 71.e1–71.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fujisawa H, Sugimura Y, Takagi H. et al. Chronic hyponatremia causes neurologic and psychologic impairments. J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 27: 766–780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kinsella S, Moran S, Sullivan MO. et al. Hyponatremia independent of osteoporosis is associated with fracture occurrence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5: 275–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ayus JC, Armstrong D, Arieff AI. Hyponatremia with hypoxia: effects on brain adaptation, perfusion, and histology in rodents. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 1319–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Swart RM, Hoorn EJ, Betjes MG. et al. Hyponatremia and inflammation: the emerging role of interleukin-6 in osmoregulation. Nephron Physiol 2011; 118: 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, Arrigain S. et al. Cause-specific deaths in non-dialysis-dependent CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 2512–2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Navaneethan SD, Schold JD, Arrigain S. et al. Body mass index and causes of death in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2016; 89: 675–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mandai S, Kuwahara M, Kasagi Y. et al. Lower serum sodium level predicts higher risk of infection-related hospitalization in maintenance hemodialysis patients: an observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol 2013; 14: 276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.