NICHD Fetal Growth Studies–Singletons and Twins–in a nutshell

The primary aims of the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies–Singletons and Twins were: in singletons, to establish a standard for normal fetal growth; and in dichorionic twins, to describe empirically their growth trajectory compared with singleton trajectories, based on the standard.

Recruitment occurred between 8 and 13 weeks’ gestation at 12 clinical sites (eight for twins) with enrolment of: 2334 low-risk women with singleton pregnancies stratified by four self-identified racial/ethnic groups (Caucasian, African American, Hispanic, Asian); 468 obese women; and 171 women with dichorionic twins.

Singleton pregnancies had five follow-up visits; twin pregnancies had an additional follow-up visit.

Using a standard protocol and after intensive sonographer training and credentialling, serial ultrasounds for fetal biometry were performed. Maternal anthropometric measurements, including fundal height, were taken serially, and neonatal measurements were taken soon after birth. Women completed demographic, reproductive and pregnancy history questionnaires at enrolment, and dietary intake, changes in health status, health behaviour, depression and stress questionnaires serially at each study visit. Longitudinal blood specimens were collected in all women, as well as placenta and cord blood in a subset of singletons and all twins.

Data will be made Accessible in documented repositories and electronic archives after completion of the studies’ analytical phases.

Why was the cohort set up?

Optimal fetal growth is a foundation for long-term health, whereas abnormal growth affects disease risk across the lifespan. Both fetal growth restriction and overgrowth are associated with increased fetal, infant and child mortality and morbidity,1,2 as well as being factors in reproductive disorders and later-onset diseases. Population-level data suggest a relationship between diminished birth size and chronic disorders, including hypertension,3,4 supporting the early origins of health and disease research paradigm.5

Despite the importance of adequate fetal growth, no US standards for ultrasound-measured fetal growth exist. Existing natality references describe the gestational age distribution of birthweight for all fetuses, including growth-restricted preterm infants and infants of diabetic mothers.6–8 Existing ultrasound references have generally been constructed from local convenience samples which are not representative of the US population. In contrast, ultrasonographic standards can be purposefully developed to reflect optimal growth by restricting study populations to healthy, normal-weight women at low risk for adverse pregnancy complications with fetuses free of anomalies.9 Many factors, including race/ethnicity, have been linked to an increased risk for abnormalities in fetal growth as variously defined,10–12 and the lack of a standard precludes fuller interpretation of these findings. Furthermore, an ultrasonographic standard is especially vital given changing sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of US maternal populations, including increasing shares of births to older, non-White and heavier mothers relative to earlier cohorts.13–14

To address these needs, we designed the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Fetal Growth Studies. The central goal was to establish standards for fetal growth and size-for-gestational age. The study was designed with adequate statistical power to allow for identification of any differences among non-Hispanic White (self-identified Caucasian), non-Hispanic Black (self-identified African American), Hispanic and Asian or Pacific Islander singleton fetuses in size and proportion, and to create separate standards as necessary. Our working hypothesis was that differences in fetal dimensions and proportions would mirror those found among adults of various race/ethnicities, and this would be important in evaluating the adequacy of fetal growth. An additional cohort of low-risk obese women, unselected by race/ethnicity, was also recruited. The scope and richness of the research design facilitated a number of secondary objectives, including: (i) constructing standards for fundal height; (ii) collecting blood samples for an aetiological study of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in the singleton and obese cohorts and development of a bioassay-based prediction model for GDM and fetal growth; (iii) investigating the impact of maternal obesity on fetal growth; (iv) collecting placental tissues and cord blood in selected cases and controls for an aetiological study of idiopathic intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR); and (v) collecting dietary intake data to study the association between maternal nutrition and fetal growth.

NICHD Fetal Growth Study–Twins

Understanding fetal growth in twin gestations is important for the same basic reasons that apply to singletons (influential determinant of health and disease in the perinatal period, childhood and adult life), but also because of uncertainty about whether twin fetal growth should be evaluated similarly to singleton growth.15 Twin gestations are significant in scale, representing 3.4% of US births in 2013.16 The infant mortality rate is higher in twins than singletons (23.6 versus 5.4 per 1000 live births), as is the rate of cerebral palsy (7.0 versus 1.6 per 1000 live births).17–18 Cross-sectional US natality data demonstrate that after 28 weeks’ gestation, twins are born with lower mean birthweights than singletons, with the mean for monochorionic twins being less than that for dichorionic twins. The gap widens with increasing gestational age, implying that growth slows at the beginning of the third trimester in twin gestations.19 Yet such cross-sectional studies based on birth weight do not convey the longitudinal pattern of in utero fetal growth from early in pregnancy and cannot adequately assess early-onset growth abnormalities. The data are inherently biased by preterm deliveries associated with complications that affect fetal growth and by iatrogenic preterm deliveries because of suspected growth restriction, especially in monochorionic twins. Instead, systematic evaluation and estimation of growth trajectories in twins require longitudinal ultrasound measurements across gestation (and performed in multiple clinical centres, to ensure appropriate representation of population characteristics). Such data for contemporary populations are uncommon.20–21 No study of twins with a rigorous design, including training of sonographers, standardization of ultrasound measurements and assessment of quality control, has been conducted previously.

As a part of the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies therefore, the NICHD, in collaboration with eight institutions, conducted a prospective cohort study of dichorionic twin gestations. The main objective was to empirically define the predominant trajectory of fetal growth in twins using longitudinal two-dimensional ultrasound, and to compare the twin fetal growth trajectories with the singleton growth standard developed by our group.22 Monochorionic twins were not included in the cohort because of their low incidence and the need to oversample them for comparison with dichorionic twins, which would have required extending the recruitment period and/or expansion to more sites.

Who is in the cohort?

A prospective cohort study, with longitudinal data collection, was designed to recruit singleton pregnant women between July 2009 and January 2013 from 12 participating US.clinical sites: Columbia University (NY), New York Hospital, Queens (NY), Christiana Care Health System (DE), Saint Peter’s University Hospital (NJ), Medical University of South Carolina (SC), University of Alabama (AL), Northwestern University (IL), Long Beach Memorial Medical Center (CA), University of California, Irvine (CA), Fountain Valley Hospital (CA), Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (RI) and Tufts University (MA). Implementation of the twin protocol began on 1 February 2012 at eight of the 12 sites and ended on 31 January 2013. Both study protocols were reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at NICHD and each of the clinical sites. The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA).

Table 1 lists the detailed eligibility and exclusion criteria for both the singleton and twin cohorts. A total of 2802 women with singletons were recruited. This sample consists of 2334 low-risk women with pre-pregnancy body mass indices (BMI) that fell in the normal or overweight range (BMI 19–29.9 kg/m2) and 468 obese women (BMI 30–44.9 kg/m2) without major pre-existing conditions. Sufficient numbers of low-risk participants were recruited from each of four self-identified racial/ethnic groups: Caucasian (n = 614), African American (n = 611), Hispanic (n = 649) and Asian (n = 460), to allow for the development of separate standards if appropriate. The cohort of obese women was recruited to augment the numbers available for the study of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) aetiology and as a unique cohort to study the effects of maternal obesity and nutrition on gravid conditions and fetal growth. There were 171 women with dichorionic twins recruited into the study. No restrictions were placed on the racial/ethnic distributions of the obese women or the women with twins. Of those enrolled, 92% of low-risk and obese singleton and 93% of twin pregnancies were followed to completion. Table 2 summarizes the recruitment by clinical site, differentiating between the three cohorts: (i) low-risk singletons, (ii) obese and (iii) twins. Table 3 presents baseline maternal characteristics of these three study cohorts.

Table 1.

Eligibility and exclusion criteria for the NICHD Fetal Growth Study–Singletons and Twins

| Eligibility criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

All women

|

Singleton low-risk women

|

Singleton obese women

| |

Twins

|

Table 2.

Recruitment yield by cohort, race/ethnicity and clinical site

| Category | Enrolment target | Enrolled (% of target) | Drop-outsa (% of enrolled) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort (racial/ethnic group) | |||

| Low-risk women | 2504 | 2334 (93.2%) | 182 (7.8%) |

| Caucasian | 612 | 614 (100.3%) | 43 (7.0%) |

| African American | 621 | 611 (98.4%) | 50 (8.2%) |

| Hispanic | 640 | 649 (101.4%) | 45 (6.9%) |

| Asian | 631 | 460 (72.9%) | 44 (9.6%) |

| Obese women | 600 | 468 (78.0%) | 35 (7.4%) |

| Twins | 340 | 171 (50.3%) | 11 (6.4%) |

| Clinical site | |||

| Columbia University (NY) PI: Dr Ronald Wapner | 302 | 297 (98.3%) | 29 (9.8%) |

| Christiana Care Health System (DE) PI: Dr Anthony Sciscione | 580 | 569 (98.1%) | 17 (3.0%) |

| Saint Peter’s University Hospital (NJ) PI: Dr Angela Ranzini | 200 | 200 (100.0%) | 8 (4.0%) |

| New York Hospital, Queens (NY) PI: Dr Daniel Skupski | 193 | 181 (93.8%) | 25 (13.8%) |

| Medical University of South Carolina (SC) PI: Dr Roger Newman | 349 | 349 (100.0%) | 34 (9.7%) |

| University of Alabama (AL) PI: Dr John Owen | 236 | 232 (98.3%) | 15 (6.5%) |

| Northwestern University (IL) PI: Dr William Grobman | 427 | 385 (90.2%) | 38 (9.9%) |

| University of California, Irvine (CA) PI: Dr Deborah Wing | 139 | 74 (53.2%) | 6 (8.1%) |

| Long Beach Memorial Medical Center (CA) PI: D. Michael P. Nageotte | 441 | 393 (89.1%) | 28 (7.1%) |

| Fountain Valley Hospital (CA) PI: Dr Deborah Wing | 145 | 80 (55.2%) | 17 (21.3%) |

| Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island (RI) PI: Dr Edward Chien | 289 | 187 (64.7%) | 8 (4.3%) |

| Tufts University (MA) PI: Dr Sabrina Craigo | 38 | 13 (34.2%) | 3 (23.1%) |

aParticipants lost to follow-up, voluntary withdrawals or delivered at a different hospital.

Table 3.

Select baseline maternal characteristics by cohort

| Characteristic | Low-risk singletons (n = 2334) n (%) | Obese (n = 468) n (%) | Twins (n = 171) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White/non-Hispanic | 604 (26.0) | 136 (29.2) | 93 (54.4) |

| Black/non-Hispanic | 593 (25.5) | 169 (36.3) | 36 (21.1) |

| Hispanic | 451 (19.4) | 91 (19.5) | 16 (9.4) |

| Asian | 427 (18.4) | 5 (1.1) | 8 (4.7) |

| Multiracial | 247 (10.6) | 65 (13.9) | 18 (10.5) |

| Native-born USA | |||

| Yes | 1 538 (66.0) | 376 (80.5) | 143 (83.6) |

| No | 792 (34.0) | 91 (19.5) | 28 (16.4) |

| Age (years) | |||

| <20 | 134 (6.3) | 28 (6.5) | 4 (2.6) |

| 20–29 | 1029 (48.5) | 232 (54.0) | 46 (30.3) |

| 30–39 | 939 (44.2) | 163 (37.9) | 93 (61.2) |

| 40–44 | 21 (1.0) | 7 (1.6) | 9 (5.9) |

| Mean (±SD) | 28.20 (5.47) | 27.92 (5.60) | 31.61 (6.08) |

| Self-reported height (cm) | |||

| Quartile 1 (134.6–157.5) | 428 (18.4) | 84 (18.0) | 14 (8.2) |

| Quartile 2 (157.5–162.6) | 628 (26.9) | 100 (21.4) | 41 (24.0) |

| Quartile 3 (162.6–167.6) | 572 (24.5) | 152 (32.5) | 43 (25.1) |

| Quartile 4 (167.6–188.0) | 703 (30.2) | 131 (28.1) | 73 (42.7) |

| Mean (±SD) | 162.53 (7.10) | 162.96 (6.96) | 165.09 (6.83) |

| Self-reported pre-pregnancy weight (kg) | |||

| Quartile 1 (39.6–56.6) | 76 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (5.4) |

| Quartile 2 (56.7–63.6) | 1 467 (64.2) | 0 (0.0) | 64 (38.6) |

| Quartile 3 (63.7–70.9) | 707 (30.9) | 29 (6.2) | 38 (22.9) |

| Quartile 4 (71.0–122.6) | 36 (1.6) | 437 (93.8) | 55 (33.1) |

| Mean (±SD) | 23.63 (3.09) | 34.54 (4.01) | 27.60 (7.07) |

| BMI (kg/m2): | |||

| <19.0 | 76 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (5.4) |

| 19.0–24.9 | 1467 (64.2) | 0 (0.0) | 64 (38.6) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 707 (30.9) | 29 (6.2) | 38 (22.9) |

| ≥30.0 | 36 (1.6) | 437 (93.8) | 55 (33.1) |

| Mean (±SD) | 23.63 (3.09) | 34.54 (4.01) | 27.60 (7.07) |

| Parity (# births) | |||

| 0 | 1 149 (49.2) | 170 (36.3) | 96 (56.1) |

| 1 | 792 (33.9) | 151 (32.3) | 54 (31.6) |

| 2 | 279 (12.0) | 85 (18.2) | 13 (7.6) |

| 3 | 114 (4.9) | 62 (13.2) | 8 (4.7) |

| Mean (±SD) | 0.74 (0.92) | 1.13 (1.16) | 0.63 (0.89) |

| Using birth control when became pregnant | |||

| Yes | 245 (10.5) | 86 (18.4) | 14 (8.2) |

| No | 2 086 (89.5) | 381 (81.6) | 157 (91.8) |

| Marital status | |||

| Never married | 500 (21.5) | 132 (28.3) | 32 (18.7) |

| Married/living as married | 1 769 (75.9) | 313 (67.0) | 135 (78.9) |

| Divorced/separated | 62 (2.7) | 22 (4.7) | 4 (2.3) |

| Education | |||

| <High school | 253 (10.8) | 73 (15.6) | 12 (7.0) |

| High school/GED | 404 (17.3) | 109 (23.3) | 22 (12.9) |

| Some college/associates degree | 683 (29.3) | 167 (35.8) | 29 (17.0) |

| College undergraduate | 565 (24.2) | 80 (17.1) | 70 (40.9) |

| Postgraduate college | 428 (18.3) | 38 (8.1) | 38 (22.2) |

| Family income | |||

| ≤$29 999 | 562 (28.2) | 145 (34.3) | 35 (22.6) |

| $30 000–49 999 | 340 (17.1) | 112 (26.5) | 9 (5.8) |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 245 (12.3) | 66 (15.6) | 14 (9.0) |

| $75 000–$99 999 | 265 (13.3) | 40 (9.5) | 18 (11.6) |

| ≥$100 000 | 580 (29.1) | 60 (14.2) | 79 (51.0) |

| Health insurance | |||

| Private/managed care | 1 239 (57.6) | 220 (50.9) | 112 (70.0) |

| Medicaid; other | 864 (40.1) | 200 (46.3) | 45 (28.1) |

| Self-pay | 49 (2.3) | 12 (2.8) | 3 (1.9) |

| Currently paid jobs | |||

| 0 | 810 (34.7) | 171 (36.7) | 37 (21.6) |

| 1 | 1 421 (60.9) | 279 (59.9) | 126 (73.7) |

| ≥2 | 102 (4.4) | 16 (3.4) | 8 (4.7) |

SD, standard deviation; GED, General Educational Developmen.

How often have they been followed up?

Research nurses at the 12 clinical sites approached women between 18 and 40 years of age who presented for their first prenatal visit at less than 13 weeks’ gestation. A screening ultrasound scan was performed between 10 and 13 weeks to confirm gestational age, using strict dating criteria (Table 1). Eligible women with an in utero singleton pregnancy, who gave informed consent to participating in the study, were then randomized to one of four groups (designated A, B, C and D) for purposes of scheduling visits (Table 4). The design enabled representative biometric measurements corresponding to every week of gestation from weeks 15 to 42, and affords a more precise estimation of velocity, without subjecting each participant to weekly ultrasounds. Study participants were asked to return to the hospital for five follow-up visits during their pregnancies, at times specified based on group assignments, with each visit allowed to occur within a 2-week time window surrounding the target gestational age (Table 4). Eligible women with an in utero twin pregnancy were randomized to one of two groups (designated A or B) and asked to return to the hospital for follow-up visits at six specified times over the course of pregnancy, based on the group assignment (Table 4).

Table 4.

Follow-up second and third trimester ultrasound visit schedule for singleton and twin pregnancies by randomization group

| Singleton | |||||

| Group (N) | Targeted gestational week for ultrasound examination | ||||

| A (581) | 16 (15 to 17) | 24 (23 to 25) | 30 (29 to 31) | 34 (33 to 35) | 38 (37 to 39) |

| B (582) | 18 (17 to 19) | 26 (25 to 27) | 31 (30 to 32) | 35 (34 to 36) | 39 (38 to 40) |

| C (581) | 20 (19 to 21) | 28 (27 to 29) | 32 (31 to 33) | 36 (35 to 37) | 40 (39 to 41) |

| D (590) | 22 (21 to 23) | 29 (28 to 30) | 33 (32 to 34) | 37 (36 to 38) | 41 (40 to 42) |

| Twin | ||||||

| Group (N) | Targeted gestational week for ultrasound examination | |||||

| A (84) | 16 (15 to 17) | 20 (19 to 21) | 24 (23 to 25) | 28 (27 to 29) | 32 (31 to 33) | 35 (34 to 36) |

| B (87) | 18 (17 to 19) | 22 (21 to 23) | 26 (25 to 27) | 30 (29 to 31) | 34 (33 to 35) | 36 (35 to 37) |

What has been measured?

Table 5 summarizes the broad categories of data collected at enrolment, during each of the follow-up visits, at delivery andfor select participants–postpartum. At each visit, an interview was conducted using a standardized and structured questionnaire to collect information on maternal demographic characteristics, reproductive and pregnancy history, health behaviour, depression and stress. Physical activity was quantified by means of the 36-item Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire.23 Participants were screened for depression using the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale24 and perceived stress using the Perceived Stress Scale.25 Both instruments are reported to be valid and reliable.23,26 At enrolment, participants were asked to complete a self-administered Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ)27 to assess maternal diet both before pregnancy and during the first trimester. Participants in the singleton cohort were subsequently asked to complete four automated self-administered 24-h dietary recalls (ASA24)–twice during the second trimester and twice more during the third trimester [https://asa24.westat.com/], and those in the twin cohort completed an FFQ at their second (19.0–24.9 weeks) and fifth (31.0–34.9 weeks) study visits. Maternal anthropometric measurements, including fundal height, were taken serially and neonatal measurements were obtained between 12 and 24 h after delivery. Longitudinal blood specimens were collected in all women, as well as placenta and cord blood in a subset of singletons and all twins. Finally, pregnancy and neonatal outcomes were determined by abstracting the prenatal medical records and inpatient hospital records of antepartum, delivery and neonatal admissions using a standardized data collection instrument.

Table 5.

Overview of the NICHD Fetal Growth Study–Singletons and Twins

| Enrolment (8–13 weeks) | 1st follow-up visit | 2nd follow-up visit | 3rd follow-up visit | 4th follow-up visit | 5th follow-up visit | 6th follow-up visitb | Delivery | 6 weeks postpartum (GDM cases and controls only)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | ||||||||

| Baseline Interview | Interview | Interview | Interview | Interview | Interview | Interview | Chart abstraction | Interview |

| FFQ | ASA24a | ASA24a FFQb | ASA24a | ASA24a | FFQb | |||

| Ultrasound at 10–13 weeks | Ultrasound | Ultrasound | Ultrasound | Ultrasound | Ultrasound | Ultrasound | ||

| Maternal anthropometry | Maternal anthropometry, fundal height | Maternal anthropometry, fundal height | Maternal anthropometry, fundal height | Maternal anthropometry, fundal height | Maternal anthropometry, fundal height | Maternal and neonatal anthropometry | Maternal anthropometry | |

| Blood sample | Blood sample (fasting ≥ 8 h) | Blood samplea | Blood sampleb | Blood samplea | Blood sampleb | Blood sampleb | Blood sample | |

| Placenta tissue and cord bloodc | ||||||||

FFQ, Food Frequency Questionnaire; ASA 24, 24-h dietary recall; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction.

aSingleton cohort only.

bTwin cohort only.

cCollected for all singleton IUGR cases and controls and for all twins. For all same-sex twin pairs, buccal swabs were collected if the placenta was not available, to determine zygosity.

Ultrasound examinations were conducted at enrolment and each of the follow-up visits. At each examination, two-dimensional (2D) biometric measurements and three-dimensional (3D) volumes were obtained using standard operating procedures and identical equipment (Voluson E8 GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) using a transabdominal curved multi-frequency volume transducer (RAB 4–8 MHz) and endovaginal multi-frequency volume transducer (RIC 6–12 MHz). All measurements and images were captured using a study-designed application of the ViewPoint (GE Healthcare) software and electronically transferred to the image coordinating center (Emmes Corporation, Rockville, MD) for storage and further processing. For the twin cohort, care was taken to allow the research ultrasounds to be reported to the clinical provider, recognizing that women with twins would be undergoing routine sonographic surveillance regardless of the study and might prefer not to have routine clinical sonograms in addition to their study sonograms. The quality of the ultrasound measures was guaranteed by implementation of: (i) a comprehensive quality control (QC) protocol for ante hoc training and credentialling of all site sonographers, developed by the sonology centre at Columbia University; and (ii) a rigorous protocol for post hoc quality assurance (QA), whereby a random sample of all scans, stratified by clinical site and visit, was re-measured for accuracy and reliability.28Table 6 provides additional information on the data collected over the course of this study.

Table 6.

Summary of measurements for the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies–Singletons and Twins

| In-person interviews (enrolment and follow-up visits) | Maternal demographic characteristics, reproductive and pregnancy history, health behavior |

| Physical activity | |

| Stress and depression | |

| Nutrition status both before and during pregnancy | |

| Ultrasound measures | Standardized evaluation at enrolment: crown-rump length (CRL), head circumference (HC), outer to inner biparietal diameter (BPD), abdominal circumference (AC) and femur length (FL) |

| Other aspects of the evaluation included analysis of amniotic fluid (AFI, GVP), uterine artery Doppler, an assessment of placental location, and documentation of any uterine fibroids or placental abruption | |

| The second and third trimester ultrasound examinations measured the same core biometric parameters, with analysis of umbilical artery Doppler velocimetry | |

| Three-dimensional (3D) volumes were acquired for the fetus and the gestational sac at enrolment, as well as for fetal limbs, cerebellum and abdomen during each of the follow-up visits | |

| Anthropometry (maternal and neonatal) | Baseline maternal anthropometric assessment: height (using a portable stadiometer), weight (using an electronic scale), waist (natural waist and over the iliac crest), hip circumference, mid upper arm circumference and triceps and subscapular skinfold thicknesses (using a Lange skinfold caliper) |

| Follow-up visits: weight, arm measurements and fundal height measured along two axes: from the fundus to the top of the symphysis pubis (research, taken first), and from the top of the fundus to the top of the symphysis pubis (clinical, taken second) | |

| Delivery: weight, waist, hip, and arm measurements | |

| Neonatal measures: weight, length, head circumference, chest circumference (level of the nipples), abdominal circumference (level midway between the xiphisternum and umbilicus), umbilical circumference, subscapular skinfold thickness, abdominal flank skinfold thickness, upper arm length, mid upper arm circumference, triceps skinfold thickness, upper thigh length, mid upper thigh circumference and anterior thigh skinfold thickness | |

| Biospecimens | Singleton cohort: |

| 20-ml blood samples from the low-risk women, 30-ml from the obese women | |

| Blood samples processed, according to a standardized protocol, to extract serum, plasma, buffy coat and red blood cells within 30 min of collection, and stored at −80°C | |

| Women diagnosed with GDM, and a comparison group, asked to donate 20-ml blood samples at the 6-week postpartum visit | |

| Twin cohort: | |

| 29-ml blood samples (10 ml for serum; 10 ml for plasma, buffy coat and red blood cells; 4 ml for CBC and differential; and 5 ml for PAXgene RNA) | |

| Placenta and cord blood | Singleton cohort: |

| Obtained for each fetus diagnosed with IUGR (i.e. EFW below the 10th percentile) and a control (the next daytime delivery following an IUGR case) | |

| Placental processing and cord blood collection, using a standardized protocol, done within 1 h of delivery | |

| Cord blood obtained before the placenta was delivered, in a 10-ml EDTA collection tube and refrigerated at 4°C | |

| Detailed photographs of the placenta obtained for gross evaluation | |

| Five site biopsies placed in tissue culture media and processed for karyotyping. Five placental parenchymal biopsies placed i formalin. Five biopsies of placenta contiguous to the parenchymal samples placed in RNALater® and frozen at −70° C for future RNA and gene expression evaluation | |

| Twin cohort: | |

| Placental processing and cord blood collection, using a standardized protocol, done within 1 h of delivery | |

| Cord blood collected separately for each twin: 16.5 ml (3.5 ml for serum; 4 ml for plasma, buffy coat and red blood cells; 4 ml for CBC and differential; and 5 ml for PAXgene RNA), and refrigerated at 4°C | |

| Detailed photographs of the placenta obtained for gross evaluation | |

| Four biopsies from each placenta placed in PAXGene® Tissue Container Kits | |

| One biopsy from each placenta placed in normal saline for zygosity testing on same-sex dichorionic pregnancies. If the placenta was not available, buccal swab specimens were obtained for zygosity determination |

CBC, complete blood count; EFW, estimated fetal weight.

What has it found? Key findings and publications

Ultrasound quality assurance (QA) ensures accurate and reliable measures

Rigorous quality control (QC) procedures for training and credentialling of sonographers, coupled with QA oversight, ensured that measurements acquired longitudinally for singletons are accurate and reliable for establishment of an ultrasound standard for singleton fetal growth.28

The low rates of measurement variability and technical errors of measurement (TEM) reinforce the validity of the fetal growth trajectories and significance of the racial/ethnic differences in fetal growth observed in the study.22 Of the measurements used most commonly to estimate fetal weight, abdominal circumference (AC, a soft tissue measure) was found to be the most variable and least reliable. Models and studies that emphasize AC or AC velocity as a major predictor of fetal outcome should take this into account.

Race/ethnicity matters: significant racial/ethnic-specific differences in fetal growth detected early in pregnancy

In uncomplicated pregnancies, the sizes of individual fetal dimensions, i.e. biparietal diameter (BPD), head circumference (HC), AC, humerus length (HL) and femur length (FL), exhibited significant differences by broad categories of maternal self-identified race/ethnicity as early as 10–16 weeks’ gestation, and the established trajectories continue to diverge throughout gestation.22 For example, the earliest racial/ethnic-specific differences were observed for HL and FL, which were measured as longer on average for fetuses of African American mothers relative to others, starting at 10 weeks’ gestation. These growth curves were estimated for singleton fetuses born at term to low-risk mothers (optimum physical and socioeconomic status) without pregnancy complications or neonatal conditions that could affect fetal growth. Such pregnancies are presumed to support optimal fetal growth unconstrained by environmental factors and constrained only by the limitations of maternal metabolism and the intrauterine environment.29 Thus, our observed racial/ethnic differences primarily reflect maternal intrinsic characteristics such as age, height and subcutaneous fatness, possibly as shaped by evolutionary processes.29

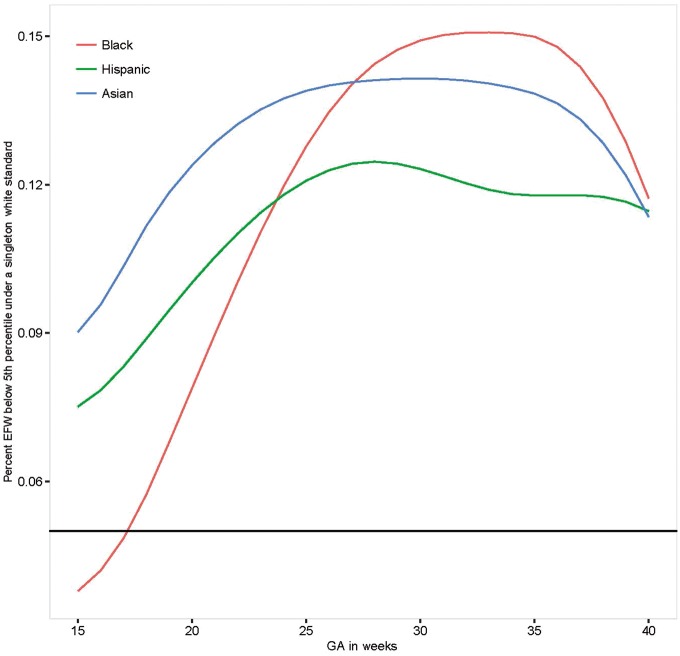

To highlight the clinical implications of our findings, we estimated the degree of re-classification that would be introduced if we used our Caucasian standard for non-Caucasian fetuses, along the lines of the Hadlock reference.30Figure 1 illustrates that approximately 5% to 15% of all fetuses would be classified as being <5th percentile for estimated fetal weight (EFW) when using the Caucasian standard, across gestation.

Figure 1.

Percentage of non-White fetuses below the 5th percentile of the Non-Hispanic White Standard. GA, gestational age.

Our inability to substantiate a single standard for fetal growth, particularly in the third trimester when fetuses undergo active clinical surveillance for growth deviations associated with maternal complications,31 underscores the potential for inappropriate classification of fetuses and antenatal testing and/or delivery. Although our findings are consistent with other countries’ assessments of racial/ethnic or regional differences in fetal growth,10,11,32,33 they differ from the assumption of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. This study recruited low-risk pregnant women from eight geographically diverse populations, and pooled ultrasonographic data to construct a single standard predicated on no assumed differences in crown-rump length (CRL), HC or neonatal length.34,35 However, as recently reported, even a small difference in the distribution between sites has a large effect on estimating percentiles (e.g., 5th or 95th centile).36 These reported calculations showed a similar degree of misclassification as seen in our results.

In summary, these findings support the development of standards by race/ethnicity for early identification of potential fetal growth abnormalities and to mitigate over-diagnosis of IUGR and unnecessary clinical interventions.

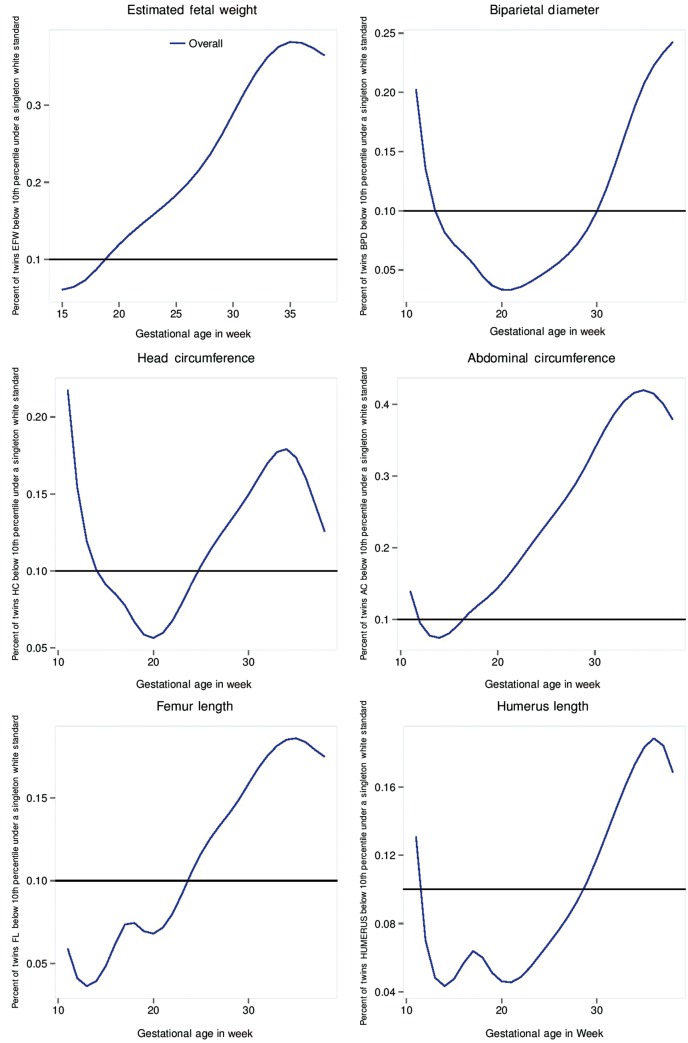

Asymmetrical growth pattern in twin gestations, evident at 32 weeks

The EFW and AC measurements for dichorionic twins were lower than those for singletons, beginning at 32 weeks’ gestation through to delivery.37 A key clinical implication of these findings concerns the degree of classification of dichorionic twins as small-for-gestational age (SGA), defined as an EFW < 10th percentile, if the study-generated singleton non-Hispanic White standard is used (Figure 2). Beginning at 19 weeks’ gestation, the percentage of twins with an EFW classified as <10th percentile exceeded 10%, and by 32 weeks’ gestation 34% of twins would be classified as SGA.

Figure 2.

Percentage of dichorionic twin fetuses below the 10th percentile of the Non-Hispanic White singleton standard.

The evidence reveals an asymmetrical growth pattern in twin gestations relative to singleton gestations, which is initially evident at 32 weeks, consistent with a constrained pattern of fetal growth and an intrauterine environment unable to sustain normal growth in twin fetuses.

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

The NICHD Fetal Growth Studies–Singletons and Twins are the largest US studies to date that have sought to characterize the dynamics of fetal growth, compare fetal growth among racial/ethnic groups and devise standards for biometric and maternal anthropometric parameters measured longitudinally throughout gestation. The findings are strengthened by several features of the study: a standardized protocol implemented at 12 distinctive clinical sites around the country; a high retention rate; rigorous training and credentialling of participating sonographers (who had a mean of 12 years of obstetrical ultrasonographic experience); coupled with a unique QA protocol throughout the study that assured high quality, reliable measurements necessary for the establishment of a race/ethnic-specific singleton standard and estimation of the twin growth trajectories; randomization of women to schedules for representation across gestation; and longitudinal collection of fetal biometry to allow for determining fetal growth velocity.

At the same time, the observational design of the study is a source of important limitations, including possible biases stemming from cohort selection and retention, and residual confounding factors such as physical activity. In addition, women were asked to self-identify their race/ethnicity with no further probing before the question, creating variation within a group. Therefore, caution is needed when interpreting our findings in light of the many complexities underlying racial/ethnic definitions, including the continually changing nature of the self-identified race construct and the phenotypic heterogeneity within broad racial/ethnic groups. For the twins, generalizability is restricted to dichorionic cases. Also, the generalizability of the findings to obese women with otherwise low-risk obstetrical profiles remains to be established.

Can I get hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

Pregnancy and postpartum data will be made accessible in documented repositories and electronic archives after completion of the studies’ analytical phases. The data, along with a set of guidelines for researchers applying for the data, will be posted to a data-sharing site, the NICHD/DIPHR Biospecimen Repository Access and Data Sharing [https://brads.nichd.nih.gov] (BRADS). All requests for data must include a short protocol with a specific research question and a plan for analysis. Before receiving any analytical file, all users must complete a Data Use Agreement form.

Funding

This research was supported by the NICHD Intramural Funding and included ARRA funding, contracts: HHSN275200800013C; HHSN275200800002I; HHSN27500006; HHSN275200800003IC; HHSN275200800014C; HHSN275200800012C; HHSN275200800028C; HHSN275201000009C.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Drs Jun Zhang and Roberto Romero for their earlier efforts in helping to develop the study protocol, Dr Karin Fuchs for her assistance with the credentialling of sonographers, and the research teams at all participating clinical centres including Christina Care Health Systems, University of California, Irvine, Long Beach Memorial Medical Center, Northwestern University, Medical University of South Carolina, Columbia University, New York Presbyterian Queens, St Peters’ University Hospital, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Women and Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, Fountain Valley Regional Hospital and Medical Center and Tufts University. The authors also acknowledge the Clinical Trials and Surveys Corporation and the EMMES Corporation in providing data and imaging support for this multi-site study. This work would not have been possible without the assistance of GE Healthcare Women’s Health Ultrasound and their support and training on the Voluson and Viewpoint products over the course of this study.

Conflict of interest: None of the authors or individually acknowledged individuals has any conflict with the content of this work.

References

- 1. Rossen LM, Schoendorf KC. Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in infant mortality rates in the United States, 1989–2006. Am J Pub Health 2014;104:1549–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mikkola K, Ritari N, Tommiska V, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age of a national cohort of extremely low birth weight infants who were born in 1996–1997. Pediatrics 2005;116:1391–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dennison EM, Arden NK, Keen RW, et al. Birthweight, vitamin D receptor genotype and the programming of osteoporosis. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2001;15:211–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonamy AK, Parikh NI, Cnattingius S, Ludvigsson JF, Ingelsson E. Birth characteristics and subsequent risks of maternal cardiovascular disease: effects of gestational age and fetal growth. Circulation 2011;124:2839–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. Developmental plasticity and human disease: research directions. J Intern Med 2007;261:461–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, Mor J, Kogan M. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 1996;87:163–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Talge NM, Mudd LM, Sikorskii A, Basso O. United States birth weight reference corrected for implausible gestational age estimates. Pediatrics 2014;133:844–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duryea EL, Hawkins JS, McIntire DD, Casey BM, Leveno KJ. A revised birth weight reference for the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2014;124:16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hediger M, Joseph KS. Fetal growth, measurement and evaluation. In: Buck Louis GM, Platt RW (eds). Reproductive and Perinatal Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pollack RN, Divon MY. Intrauterine growth retardation: definition, classification, an etiology. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1992;35:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Landis SH, Ananth CV, Lokomba V, et al. Ultrasound-derived fetal size nomogram for a sub-Saharan African population: a longitudinal study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009;34:379–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Norris T, Tuffnell D, Wright J, Cameron N. Modelling foetal growth in a bi-ethnic sample: results from the Born in Bradford (BiB) birth cohort. Ann Hum Biol 2014;41:481–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK. Births in the United States, 2013. NCHS data brief, no 175. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mathews TJ, Hamilton BE. First Births to Older Women Continue to Rise. NCHS data brief, no. 152. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med 2008;359:61–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Matthews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. National vital statistics reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System 2015;64:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luke B, Brown MB. The changing risk of infant mortality by gestation, plurality, and race: 1989–1991 versus 1999–2001. Pediatrics 2006;118:2488–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Petterson B, Nelson KB, Watson L, Stanley F. Twins, triplets, and cerebral palsy in births in Western Australia in the 1980s. BMJ 1993;307:1239–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alexander GR, Kogan M, Martin J, Papiernik E. What are the fetal growth patterns of singletons, twins, and triplets in the United States? Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998;41:114–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yarkoni S, Reece EA, Holford T, O’Connor TZ, Hobbins JC. Estimated fetal weight in the evaluation of growth in twin gestations: a prospective longitudinal study. Obstet Gynecol 1987;69:636–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liao AW, Brizot Mde L, Kang HJ, Assuncao RA, Zugaib M. Longitudinal reference ranges for fetal ultrasound biometry in twin pregnancies . Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67:451–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Buck Louis GM, Grewal J, Albert P, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in fetal growth, the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:449.e1–e41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Roberts DE, Hosmer D, Markenson G, Freedson PS. Development and validation of a Pregnancy Physical Activity Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:1750–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987;150:782–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983;24:385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eberhard-Gran M1, Slinning K, Eskild A. Fear during labor: the impact of sexual abuse in adult life. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2008;29:258–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Diet History Questionnaire, Version 1.0. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health, Applied Research Program, National Cancer Institute, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hediger ML, Fuchs KM, Grantz, et al. Ultrasound quality assurance (QA) for singletons in the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. J Ultrasound Med 2016;35:1725–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hanson MA, Gluckman PD. Early developmental conditioning of later health and disease: physiology of pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2014;94:1027–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hadlock FP, Harrist RB, Sharman RS, Deter RL, Park SK. Estimation of fetal weight with the use of head, body, and femur measurements – A prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;151:333–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khali A, Rezende J, Akolekar R, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides KH. Maternal racial origin and adverse pregnancy outcome: a cohort study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013;41:278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kierans WJ, Joseph KS, Luo ZC, Platt R, Wilkins R, Kramer MS. Does one size fit all? The case for ethnic-specific standards of fetal growth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008;8:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kiserud T, Piaggio G, Carroli G, et al. The World Health Organization Fetal Growth Charts: a multinational longitudinal study of ultrasound biometric measurements and estimated fetal weight. PLoS 2017;14:e1002220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Papageorghiou AT, Ohuma EO, Altman DG, et al. International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet 2014;384:869–79. Erratum in: Lancet 2014;384:1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Villar J, Papageorghiou AT, Pang R, et al. The likeness of fetal growth and newborn size across non-isolated populations in the INTERGROWTH-21st Project: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study and Newborn Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:781–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Albert PS, Grantz KL. Fetal growth and ethnic variation. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grantz KL, Grewal J, Albert PS, et al. Racial/Ethnic Standards for Fetal Growth, the NICHD Fetal Growth Studies. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:221. e1-e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]