The longitudinal course of microglial activation in the trajectory of Alzheimer’s disease is unclear. Fan et al. demonstrate two peaks: one in early MCI and another in late Alzheimer’s disease. Activated microglia in MCI may initially adopt a protective anti-inflammatory phenotype, changing to a pro-inflammatory phenotype as the disease progresses.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, microglial activation, amyloid imaging, neuropathology

Abstract

Amyloid-β deposition, neuroinflammation and tau tangle formation all play a significant role in Alzheimer’s disease. We hypothesized that there is microglial activation early on in Alzheimer’s disease trajectory, where in the initial phase, microglia may be trying to repair the damage, while later on in the disease these microglia could be ineffective and produce proinflammatory cytokines leading to progressive neuronal damage. In this longitudinal study, we have evaluated the temporal profile of microglial activation and its relationship between fibrillar amyloid load at baseline and follow-up in subjects with mild cognitive impairment, and this was compared with subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. Thirty subjects (eight mild cognitive impairment, eight Alzheimer’s disease and 14 controls) aged between 54 and 77 years underwent 11C-(R)PK11195, 11C-PIB positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans. Patients were followed-up after 14 ± 4 months. Region of interest and Statistical Parametric Mapping analysis were used to determine longitudinal alterations. Single subject analysis was performed to evaluate the individualized pathological changes over time. Correlations between levels of microglial activation and amyloid deposition at a voxel level were assessed using Biological Parametric Mapping. We demonstrated that both baseline and follow-up microglial activation in the mild cognitive impairment cohort compared to controls were increased by 41% and 21%, respectively. There was a longitudinal reduction of 18% in microglial activation in mild cognitive impairment cohort over 14 months, which was associated with a mild elevation in fibrillar amyloid load. Cortical clusters of microglial activation and amyloid deposition spatially overlapped in the subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Baseline microglial activation was increased by 36% in Alzheimer’s disease subjects compared with controls. Longitudinally, Alzheimer’s disease subjects showed an increase in microglial activation. In conclusion, this is one of the first longitudinal positron emission tomography studies evaluating longitudinal changes in microglial activation in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease subjects. We found there is an initial longitudinal reduction in microglial activation in subjects with mild cognitive impairment, while subjects with Alzheimer’s disease showed an increase in microglial activation. This could reflect that activated microglia in mild cognitive impairment initially may adopt a protective activation phenotype, which later change to a cidal pro-inflammatory phenotype as disease progresses and amyloid clearance fails. Thus, we speculate that there might be two peaks of microglial activation in the Alzheimer’s disease trajectory; an early protective peak and a later pro-inflammatory peak. If so, anti-microglial agents targeting the pro-inflammatory phenotype would be most beneficial in the later stages of the disease.

Introduction

Amnestic mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional stage between cognitively normal individuals and Alzheimer’s disease. The amyloid cascade-neuroinflammation hypothesis suggests that an increase in levels of amyloid-β, due to its excess synthesis or a failure of clearance, is the primary event and that this leads to neuroinflammation and subsequent neuronal damage. However, other studies have emphasized an early role of neuroinflammation in the disease process (Okello et al., 2009; Heneka et al., 2015).

It is now accepted that neuroinflammation plays a significant role in the Alzheimer’s disease process (Amor et al., 2010; Heneka et al., 2015). Activated microglia can adopt two main functional states: pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory states of microglial activation. It has been suggested that in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, the initial microglial activation may serve a protective function (anti-inflammatory) trying to clear the amyloid and release nerve growth factors (Hamelin et al., 2016). When this process fails due to accumulation of amyloid-β or other toxic products, there is activation of pro-inflammatory phenotypes, which release pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to self-perpetuating damage to the neurons. However, genetic data from genome-wide associations studies suggest that microglial activation may play a significant role early on in the disease and independent of amyloid pathology (Guerreiro and Hardy, 2011, 2013; Hollingworth et al., 2011a, b; Varnum and Ikezu, 2012). This is further supported by evidence from ageing brain, where microglial activation and neurodegeneration can be present in the absence of amyloid plaques (von Bernhardi et al., 2015). Epidemiological studies have shown a lower prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in people taking anti-inflammatory non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, suggesting a potential protective role of lowering neuroinflammation, although randomized trials have not shown efficacy of these agents in subjects with established Alzheimer’s disease (Jaturapatporn et al., 2012). However, no studies to date have evaluated levels of microglial activation in subjects with MCI longitudinally to assess the influence of microglial activation in the Alzheimer’s disease trajectory. We hypothesized that there is microglial activation in subjects with MCI early on in the disease process, which may decrease over time as the protective phenotype becomes ineffective, while during later stages of the Alzheimer’s disease trajectory, there is persistent increase in microglial activation.

Translocator protein (TSPO) expression in the healthy brain is very low, but it elevates after brain injury and neuroinflammation, therefore TSPO has been widely used as a PET imaging biomarker to visualize microglial activation in the CNS (Fan et al., 2015a; Varley et al., 2015). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the influence of microglial activation in Alzheimer’s disease trajectory using 11C-(R)PK11195 PET in subjects with MCI and Alzheimer’s disease and how these changes are influenced by the levels of amyloid deposition measured with 11C-PIB PET longitudinally.

Materials and methods

Eight participants who had a diagnosis of MCI based on the Petersen criteria and 14 healthy controls were recruited into this study. These subjects were compared with our previous data on eight subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (Fan et al., 2015b). All subjects underwent detailed neurological examinations, 11C-(R)PK11195 and 11C-PIB PET scans, and T1/T2 volumetric MRI to evaluate any structural lesions at baseline. Subjects with MCI and Alzheimer’s disease were followed up with repeat 11C-(R)PK11195 PET, 11C-PIB PET and MRI after 14 ± 4 months.

Image acquisition

MRI scans were acquired with a 1.5 T GE scanner (acquisition times repetition time 30 ms, echo time 3 ms, flip angle 30°, field of view 25 cm, matrix 156 × 256, voxel dimensions 0.98 × 0.98 × 1.6 mm). An ECAT EXACT HR++ (CTI/Siemens) PET scanner was used to acquire 11C-(R)PK11195 PET, while 11C-PIB scans were acquired using an ECAT EXACT HR+ scanner. T1-weighted MRI was used to generate an individualized brain atlas as detailed below, whereas T2-weighted MRI was acquired to exclude any structural abnormalities. A mean activity of 290 ± 16 MBq 11C-(R)PK11195 was injected intravenously and scanned for 60 min to generate an dynamic 11C-(R)PK11195 PET (Edison et al., 2008). For 11C-PIB PET scans, 370 ± 18 MBq 11C-PIB was injected and scanned for 90 min.

Image processing

Owing to widespread distribution of microglial activation, it is difficult to identify a single region as reference. Therefore, supervised cluster analysis was used to generate parametric images of 11C-(R)PK11195 BP (binding potentials) for each individual by extracting distributed clusters of voxels that kinetically behaved either like a normal population cortical reference input function or showed evidence of tracer retention (Anderson et al., 2007; Turkheimer et al., 2007). With the supervised clustering algorithm, the 11C-(R)PK11195 PET shows a better test-retest variability [10.6%, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) = 0.878] than unsupervised approaches (Turkheimer et al., 2007). A summed 60–90 min add image was used to create 11C-PIB standardized uptake value ratio (RATIO) maps with cerebellar cortex as the reference tissue.

Region of interest analysis

We used statistical parametric mapping software, SMP8 (http:www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and Analyze 11 (AnalyzeDirect) for image analysis. Initially, 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB PET (60–90 min) images were co-registered to the individual MRI space. Then the subjects’ MRIs were segmented to grey matter, white matter, and CSF. The grey matter binary image was created at 50% threshold. Probabilistic brain atlas in MNI space was transformed to individual MRI space. The grey matter binary image was then multiplied with the probabilistic brain atlas in Analyze11 to create an individualized object map. 11C-PIB RATIO images were created by dividing the individual PET with cerebellar grey matter 11C-PIB uptake. Finally, the 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB RATIO images were sampled in the following regions: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital cortices, anterior, posterior cingulate, thalamus striatum and hippocampus. In addition, partial volume correction (PVC) was applied to the 11C-(R)PK11195 BP PET data at baseline and during follow-up to minimize the impact of brain atrophy using PVC_SFSRR software (Shidahara et al., 2009).

Statistical parametric mapping analysis

All PET and MRI scans were then normalized into MNI space and smoothed using a 6 × 6 × 6 mm filter in SPM. Initially a cluster threshold of P < 0.05 with extent threshold of 50 voxels were applied, if the significance was reached (Supplementary Fig. 1), higher threshold was applied to delineate minimal changes. Between-group clusters of significant mean differences at a voxel level between subjects with MCI and controls were localized with SPM8 by applying the Student’s t-test with a threshold of P < 0.01 and cluster extent threshold 50 voxels for 11C-(R)PK11195 PET; and a threshold of P < 0.005 and cluster extent threshold 50 voxels for 11C-PIB. Similar thresholds were used for the follow-up PET scans. The overall change from baseline to follow-up in microglial activation and amyloid deposition were assessed using paired t-test in SPM with a threshold of P < 0.01 with an extent threshold of 50 voxels. Similar SPM analyses were performed for subjects with Alzheimer’s disease (Fan et al., 2015b).

Single subject analyses

As a classical region of interest approach for interrogating inhomogeneous microglial activation tends to underestimate the localized voxel-wise small changes within any predefined region of interest, we developed individualized SPM maps by comparing each patient against a group of healthy controls to localize significant clusters of binding change (Edison et al., 2013). VOI (volume of interest) maps for increased 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB uptake for each subject were generated by extracting the significant clusters from the single subject result in SPM8. The volume of each pathological process was calculated using Analyze11 (Fan et al., 2015a).

3D intensity T-map

We developed 3D intensity T-maps in MATLAB to demonstrate a clear visualization of the significant changes in microglial activation and amyloid between baseline and follow-up. Each 3D intensity T-map uses the SPM T-map to generate surface plots where the colour intensity and height reflects the T-score for the corresponding voxel with significant increase or decrease in the microglial activation and amyloid deposition.

Biological Parametric Mapping correlations

Voxel-wise statistical correlations between 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB RATIO were performed using the Biological Parametric Mapping (Casanova et al., 2007), which provides sophisticated voxel-wise comparison across imaging modalities with P < 0.05. To directly compare different pathological processes using PET scans, Z-score maps were created to represent the brain profiles for levels of microglial activation and amyloid deposition using the following formulae for Biological Parametric Mapping (BPM) analysis:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Z denotes Z-score map, X˙ denotes mean, and SD denotes standard deviation.

As the predefined region of interest regional mean may underestimate the true changes at voxel level, a pixel-wise Pearson correlation graph (scatter plot) between the group mean image of 11C-PIB RATIO PET and 11C-(R)PK11195 BP PET was applied in the whole cortex and in frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices. The scatter plots were generated for all subjects with MCI, subgroup of amyloid-positive subjects and subgroup of amyloid-negative subjects.

Statistical analysis

All region of interest data statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). The P-values for voxel-wise SPM comparison was corrected for family-wise error rate at cluster level. Mean differences between patients and healthy controls, as well as the regional differences between baseline and follow-up were calculated using Student’s t-test. The Pplot multiple comparison (Turkheimer et al., 2001) was applied to the regional paired t-test between baseline and follow-up 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB RATIO using Hochberg multiple comparison correction.

Results

Demographics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant group differences in age, age range or gender. The majority of subjects with MCI demonstrated a deterioration in Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score at follow-up, while one subject the MMSE score changed from 25/30 to 28/30.

Table 1.

Demographic details of subjects with MCI and control subjects

| MCI | Healthy controls 11C-PIB | Healthy controls 11C-(R)PK11195 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 8 | 14 | 8 |

| Mean age (years ± SD) | 67.7 ± 6.6 | 64.4 ± 5.9 | 65.5 ± 5.5 |

| Age range | 55–77 | 54–75 | 58–71 |

| Gender (female/total) | 4/8 | 4/14 | 4/8 |

| MMSE (mean ± SD) | 27.6 ± 1.2 | 30 | 30 |

| Amyloid load (amyloid-β+/total) | 4/8 | – | – |

MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination.

11C-(R)PK11195 PET

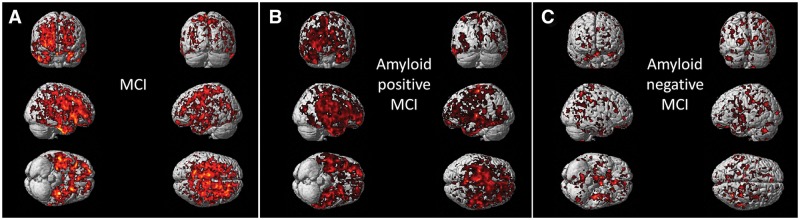

The MCI subjects as a group showed longitudinal regional reductions in microglial activation. Region of interest analysis detected significant reductions in 11C-(R)PK11195 BP in frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital cortices, anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate and hippocampus when baseline data were compared against 14 months’ follow-up (Table 2). This longitudinal reduction in microglial activation in MCI was still persistent even after the data were corrected for partial volume effect (Table 3). Apart from frontal cortex, all the above regions remained significant after correcting for multiple comparison (Turkheimer et al., 2001). Individually, region of interest analysis found that 6/8 subjects with MCI showed 20 ± 6% mean reductions of 11C-(R)PK11195 BP at follow-up. This longitudinal reduction in microglial activation from baseline to follow-up was further supported by the reduction demonstrated using paired t-test in SPM (Fig. 1A). Based on the amyloid load at baseline, there were four amyloid-positive subjects who demonstrated global increase in amyloid deposition compared with controls, while the other four showed no elevation in amyloid load in any regions of interest. When the subjects were separated as amyloid-positive and amyloid-negative subjects, the amyloid-positive group demonstrated significant reduction in microglial activation using region of interest and SPM analysis in temporal, parietal and occipital cortices, anterior cingulate, posterior cingulate and hippocampus over time. However, the amyloid-negative subject group demonstrated only small clusters of reduction in microglial activation using SPM analysis. In the amyloid-negative subjects, there was a trend of reduction in microglial activation using region of interest analysis, however, it did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1 and Table 2). 11C-(R)PK11195 PET shows a test-retest variability of 10.6% (ICC = 0.878) (Turkheimer et al., 2007). The reductions seen in microglial activation in this study are up to 33–42%; and are unlikely to be due to repeat measurements.

Table 2.

Regional 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB RATIO in subjects with MCI and healthy control subjects, and regional 11C(R)PK11195 BP in amyloid-positive and -negative MCI subjects, at baseline and follow-up

| Frontal | Temporal | Parietal | Occipital | Ant. cing. | Post. cing. | Thalamus | Striatum | Hippo. | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB RATIO in MCI subjects | |||||||||||||||||||

| PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | PK11195 | PIB | ||

| Baseline | Mean | 0.42 | 1.53 | 0.47 | 1.54 | 0.43 | 1.56 | 0.48 | 1.47 | 0.53 | 1.69 | 0.57 | 1.73 | 0.43 | 1.26 | 0.35 | 1.59 | 0.48 | 1.35 |

| SD | 0.1 | 0.58 | 0.09 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 0.07 | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.47 | 0.11 | 0.13 | |

| Increase (B vs. HC)a | 42% | 32% | 44% | 34% | 47% | 34% | 35% | 21% | 59% | 36% | 46% | 41% | 12% | 24% | 36% | 32% | 41% | 11% | |

| P-value | 0.0079* | 0.0135* | 0.0021* | 0.0060* | 0.0080* | 0.0102* | 0.0071* | 0.0325* | 0.0024* | 0.0069* | 0.0021* | 0.0056* | 0.2013 | 0.0086* | 0.0066* | 0.0030* | 0.0087* | 0.0031* | |

| Follow-up | Mean | 0.36 | 1.65 | 0.39 | 1.62 | 0.37 | 1.64 | 0.42 | 1.54 | 0.36 | 1.77 | 0.43 | 1.85 | 0.41 | 1.28 | 0.33 | 1.66 | 0.38 | 1.38 |

| SD | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.09 | 0.71 | 0.1 | 0.77 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.18 | |

| Increase (F vs. HC)a | 20% | 43% | 18% | 41% | 26% | 41% | 18% | 27% | 7% | 43% | 10% | 51% | 7% | 26% | 26% | 38% | 11% | 17% | |

| P-value | 0.114 | 0.0054* | 0.0430* | 0.0037* | 0.0500* | 0.0073* | 0.0347* | 0.0144* | 0.3113 | 0.0056* | 0.2202 | 0.0030* | 0.3323 | 0.005* | 0.0221* | 0.0024* | 0.2047 | 0.0111* | |

| HC | Mean | 0.3 | 1.16 | 0.33 | 1.15 | 0.29 | 1.16 | 0.36 | 1.21 | 0.33 | 1.24 | 0.39 | 1.23 | 0.38 | 1.02 | 0.26 | 1.2 | 0.34 | 1.18 |

| SD | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.11 | |

| B vs. F | Longitudinal changeb | −14% | 8% | −16% | 5% | −13% | 5% | −11% | 5% | −29% | 5% | −23% | 7% | −2% | 1% | −6% | 4% | −16% | 3% |

| P-value | 0.0265 | 0.0157* | 0.0088* | 0.0101* | 0.0149* | 0.0267 | 0.0204* | 0.0032* | 0.0079* | 0.0823 | 0.0062* | 0.0116* | 0.3243 | 0.3336 | 0.1445 | 0.0363 | 0.0248* | 0.0692 | |

| Regional 11C-(R)PK11195 BP in MCI subjects (Aβ+ and Aβ−) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | Aβ+ MCI | Aβ− MCI | ||

| Baseline | Mean | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.43 |

| SD | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.08 | |

| Increase (B vs. HC)a | 47% | 36% | 60% | 29% | 46% | 49% | 44% | 25% | 67% | 51% | 57% | 35% | 13% | 12% | 35% | 37% | 55% | 27% | |

| P-value | 0.0110* | 0.0601 | 0.0025* | 0.0021* | 0.0333* | 0.0396* | 0.0161* | 0.0029* | 0.0474* | 0.0364* | 0.0117* | 0.0684 | 0.2275 | 0.0105* | 0.0693 | 0.0313* | 0.0270* | 0.0515 | |

| Follow-up | Mean | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.3 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.43 |

| SD | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | |

| Increase (F vs. HC)a | 19% | 21% | 19% | 17% | 27% | 24% | 18% | 17% | −3% | 17% | 6% | 13% | 11% | 3% | 16% | 37% | 4% | 25% | |

| P-value | 0.2019 | 0.1306 | 0.0383* | 0.1078 | 0.0757 | 0.0725 | 0.0527 | 0.0504 | 0.4218 | 0.1609 | 0.3408 | 0.2313 | 0.2775 | 0.4435 | 0.135 | 0.0180* | 0.3958 | 0.0472* | |

| B vs. F | Longitudinal changeb | −19% | −11% | −25% | −9% | −13% | −16% | −18% | −6% | −42% | −22% | −32% | −16% | −2% | −8% | −14% | −1% | −33% | −2% |

| P-value | 0.0542 | 0.19 | 0.0062* | 0.1969 | 0.0389 | 0.1043 | 0.0274 | 0.2291 | 0.0418 | 0.0681 | 0.0165* | 0.1227 | 0.4521 | 0.3406 | 0.0508 | 0.4823 | 0.0117* | 0.3852 | |

Top: *Significant P < 0.05 with correction for multiple comparisons. Increase (B vs. HC)a indicates the group-wise region of interest comparison between baseline MCI patients and healthy controls, while increase (F vs. HC)a indicates the group-wise region of interest comparison between follow-up MCI patients and healthy controls. bLongitudinal change indicates the group-wise region of interest comparison between baseline and follow-up.

Bottom: *Significant P < 0.05 with correction for multiple comparisons. Increase (B vs. HC)a indicates the group-wise region of interest comparison between baseline MCI patients and healthy controls, while increase (F vs. HC)a indicates the group-wise region of interest comparison between follow-up MCI patients and healthy controls. bLongitudinal change indicates the group-wise region of interest comparison between baseline and follow-up.

Aβ+ MCI = amyloid positive MCI; Aβ−MCI = amyloid negative MCI; Ant. cing = anterior cingulate; B vs. F = baseline versus follow-up; Frontal = frontal lobe; HC = healthy controls; Hippo = hippocampus; Occipital = occipital lobe; Parietal = parietal lobe; PIB = 11C-PIB; PK11195 = 11C-(R)PK11195; Post. cing. = posterior cingulate; Temporal = temporal lobe.

Table 3.

Partial volume corrected regional 11C-(R)PK11195 in subjects with mild cognitive impairment at baseline and follow-up

| PVC 11C-(R) PK11195 BPa | Frontal lobe | Temporal lobe | Parietal lobe | Occipital lobe | Anterior cingulate | Posterior cingulate | Thalamus | Striatum | Hippocampus | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Mean | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.48 | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| SD | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.15 | |

| Follow-up | Mean | 0.41 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.35 |

| SD | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| B vs. F | Longitudinal changeb | −15% | −15% | −17% | −7% | −41% | −31% | −9% | −8% | −21% |

| P-value | 0.0389* | 0.0306* | 0.0082* | 0.1926 | 0.0085* | 0.0150* | 0.1480 | 0.0819 | 0.0475* | |

*P < 0.05; B vs. F = baseline versus follow-up. aPVC 11C-(R)PK11195 PVC BP = 11C-(R)PK11195 partial volume corrected binding potential. bLongitudinal change indicates the group-wise region of interest comparison between baseline and follow-up PVC 11C-(R)PK11195 BP.

Figure 1.

SPM analysis between baseline and follow-up microglial activation in MCI subjects. (A) Paired t-test SPM analysis between baseline and follow-up microglial activation in all subjects with MCI. (B) Paired t-test SPM analysis between baseline and follow-up microglial activation in amyloid positive subjects. (C) Paired t-test SPM analysis between baseline and follow up microglial activation in amyloid negative subjects. Supplementary Table 2 details the coordinates with their statistical results.

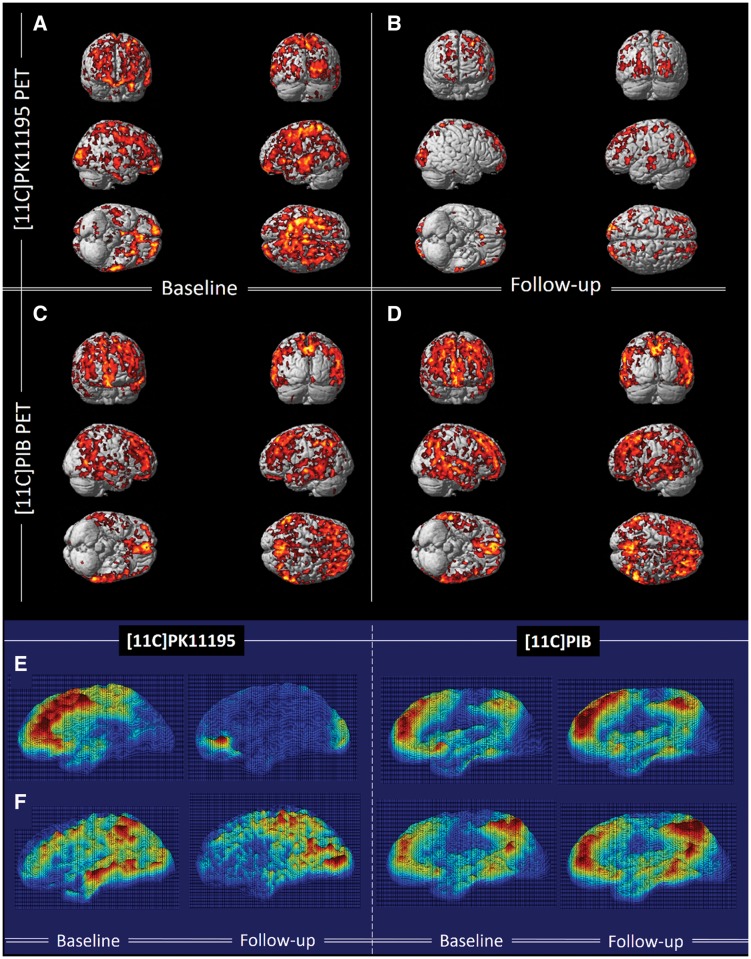

Single subject volumetric analysis found that the total number of voxels with significantly raised microglial activation decreased by 50 ± 27% during follow-up (Fig. 2E, F and Table 4). Compared to the healthy controls, SPM localized significant increases in microglial activation in subjects with MCI at both baseline and at follow-up in medial temporal lobe, hippocampus, anterior temporal lobe, posterior temporal lobe, parietal and frontal gyri at a cluster threshold of P < 0.01 and extent threshold of 50 voxels (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2.

Longitudinal changes in 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB in subjects with MCI compared to controls at baseline and follow-up. (A and B) Clusters of significantly increased 11C-(R)PK11195 BP in subjects with MCI compared to healthy controls at baseline and follow-up, respectively, with the same voxel threshold of P < 0.01 and extent threshold of 50 voxels. (C and D) Clusters of significantly increased 11C-PIB in subjects with MCI compared to healthy controls at baseline and follow-up (P < 0.0001 and extent of 200 voxels). Supplementary Table 3 details the coordinates with their statistical results. (E and F) 3D intensity T-map of 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB RATIO for two individual subjects with MCI at baseline and follow-up. The surface plot represents significant increase in the microglial activation (left) and amyloid deposition (right) against the control group at baseline superimposed on a 3D matrix at baseline and follow-up.

Table 4.

Changes in extent of area of microglial activation and the extent of area of amyloid deposition in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease and subjects with MCI between baseline and follow-up

| Patient | MCI1 (Aβ+) | MCI2 (Aβ+) | MCI3 (Aβ−) | MCI4 (Aβ−) | MCI5 (Aβ+) | MCI6 (Aβ−) | MCI7 (Aβ+) | MCI8 (Aβ−) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11C-(R)PK11195 volume | Baseline | 307 584 | 68 527 | 8894 | 136 917 | 94 941 | 230 360 | 450 468 | 61 452 |

| Follow-up | 173 297 | 55 552 | 33 710 | 56 623 | 74 585 | 30 253 | 124 229 | 138 047 | |

| Changes | −134 287a | −12 975a | 24 816a | −80 294a | −20 356a | −200 107a | −326 239a | 76 595a | |

| 11C-PIB volume | Baseline | 368 415 | 622 213 | 12 176 | 5294 | 366 916 | 20 617 | 599 768 | 24 371 |

| Follow-up | 484 441 | 633 263 | 21 246 | 15 943 | 432 670 | 13 281 | 383 028 | 18 303 | |

| Changes | 116 026a | 11 050a | 9070a | 10 649a | 65 754a | −7336a | 55 534a | −6068a | |

| Patient | AD1 | AD2 | AD3 | AD4 | AD5 | AD6 | AD7 | AD8 | |

| (Aβ+) | (Aβ+) | (Aβ+) | (Aβ−) | (Aβ+) | (Aβ+) | (Aβ+) | (Aβ+) | ||

| 11C-(R)PK11195 volume | Baseline | 204 649 | 16 943 | 99 337 | 162 536 | 341 955 | 41 803 | 312 547 | 36 998 |

| Follow-up | 26 742 | 53 223a | 373 971 | 311 870 | 83 399a | 46 645 | 829 597 | 110 810 | |

| Changes | −177 907a | 36 280a | 274 634a | 149 334a | −258 556a | 4842a | 517 050a | 73 812a | |

| 11C-PIB volume | Baseline | 338 747 | 376 803 | 217 421 | 27 454 | 36 697 | 273 064 | 347 069 | 560 597 |

| Follow-up | 157 210 | 374 892 | 225 236 | 92 410 | 15 648 | 341 343 | 366 402 | 1 094 708 | |

| Changes | −181 537a | −1911a | 7815a | 64 956a | −210 49a | 68 279a | 19 333a | 534 111a | |

aRepresent the changes in number of significant voxels between baseline and follow-up; Aβ+ = amyloid-β- positive MCI; Aβ− = amyloid- negative MCI.

Subjects with Alzheimer’s disease showed 30% (P < 0.03) higher microglial activation compared to healthy controls in four cortices, hippocampus and striatum at baseline, while this microglial activation increased to 46% (P < 0.01) compared to healthy controls after 14 months’ follow-up as previously reported (Supplementary Table 1). Six of eight subjects with Alzheimer’s disease individually showed a longitudinal increase in the total volume of microglial activation measured by single subject volume of interest analysis (Table 4). (Fan et al., 2015b).

11C-PIB PET

Longitudinally, subjects with MCI showed ∼6% increases in amyloid deposition in frontal lobe, temporal lobe, occipital lobe and posterior cingulate at region of interest level based on the paired t-test (Table 2). Individually, six subjects with MCI who experienced longitudinal decreases in microglial activation demonstrated small increases (6%) in mean 11C-PIB uptake across regions of interest, including posterior cingulate, striatum, hippocampus and frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices. Volume of interest analysis demonstrated a 39% increase in the total number of voxels with significantly increased amyloid deposition. Interestingly, one patient (Patient MCI8) who revealed a longitudinal increase in microglial activation (both regional BP and larger volume of microglial activation using single subject SPM analysis) during follow-up, showed a 2% reduction in mean amyloid uptake RATIO and a 26% reduction in the total number of voxels (using single subject SPM) over time (Table 4). Similar to Alzheimer’s disease subjects (Fan et al., 2015b), subjects with MCI also demonstrated whole brain elevation of amyloid deposition compared with healthy controls at baseline and follow-up (Fig. 2C, D and Table 2).

Correlation

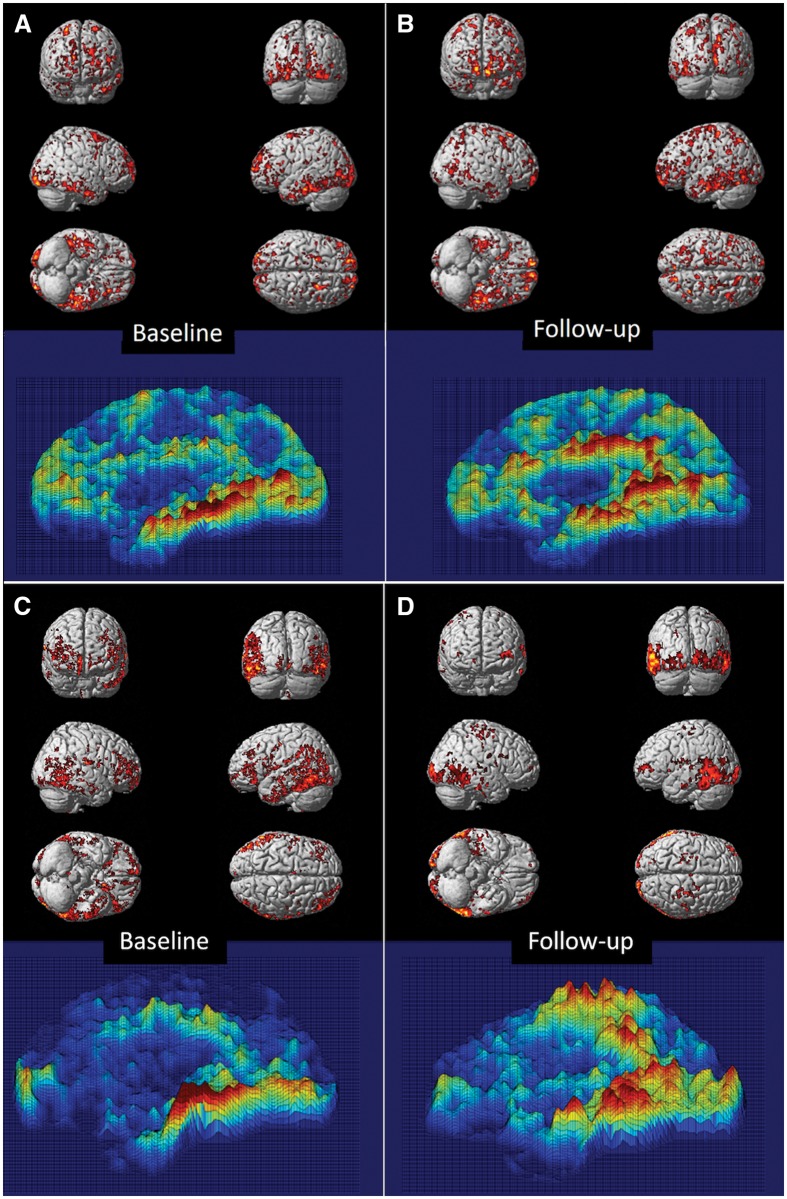

In subjects with MCI, BPM revealed a positive correlation between microglial activation and amyloid deposition at baseline in frontal, temporal and occipital lobe at threshold of P < 0.05 (Fig. 3A). At follow-up, the clusters with a positive correlation at baseline had expanded in frontal, temporal, and parietal cortical regions using the same threshold (Fig. 3B). In subjects with Alzheimer’s disease, clusters of microglial activation were positively correlated with amyloid deposition mainly in temporal lobe, parietal lobe and occipital lobe at baseline, and this positive correlation has persisted at follow-up (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Voxel-based correlation between 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB uptake. BPM-positive correlation between microglial activation and amyloid deposition superimposed on a SPM render brain image, along with 3D intensity T-map of BPM correlation in sagittal view in MCI and Alzheimer’s disease cohort. (A and B) Positive correlations between 11C-PIB RATIO and 11C-(R)PK11195 BP in subjects with MCI at baseline and follow-up, respectively, at a cluster threshold of P < 0.05 with an extent threshold of 50-voxel. (C and D) Positive correlations between 11C-PIB RATIO and 11C-(R)PK11195 BP in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease at baseline and follow-up, respectively, at a cluster threshold of P < 0.05 with an extent threshold of 50-voxel. Supplementary Table 4 details the significant clusters.

Using pixel-wise correlation, we found significant correlation (Pearson) (r = 0.37, P < 0.0001) between 11C-(R)PK11195 BP and 11C-PIB RATIO in the composite cortical region (combining frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortical region), and individually in all the four cortical regions in MCI subjects with MCI (Supplementary Fig. 2A). When we separated the MCI subjects based on amyloid status, amyloid positive MCI subjects demonstrated even more significant correlation (r = 0.53, P < 0.0001) in the composite cortex and individually in different cortices, while amyloid negative MCI subjects failed to show correlation between amyloid deposition and microglial activation (Supplementary Fig. 2B).

Discussion

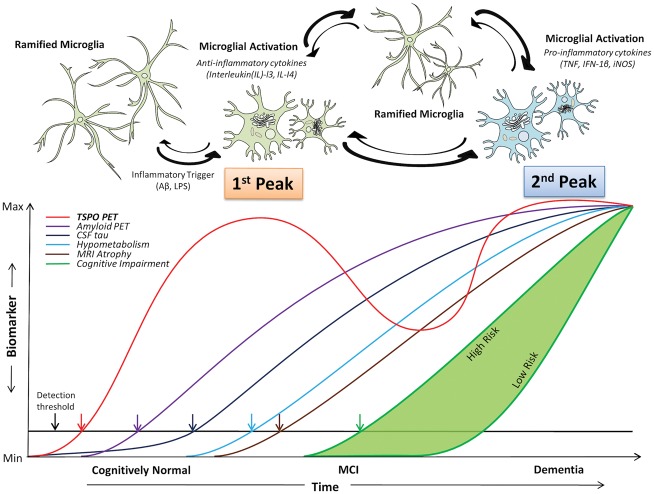

In this study, we have detected a longitudinal reduction in microglial activation in a majority of our subjects with MCI, associated with a marginal increase in amyloid load. This contrasted with subjects with Alzheimer’s disease who showed an increase in their microglial activation over 14 months (Fan et al., 2015b). These findings could be explained by the notion that there is initially protective microglial activation in the prodromal stage of Alzheimer’s disease trying to clear the amyloid, which then fails, while during the later stages of disease there is progressive increase in cidal pro-inflammatory microglial activation. This study also demonstrates that microglial activation is positive correlated with amyloid load. Such an association is compatible with microglial cells being activated by amyloid, but some of the microglial activation could also occur independently of amyloid deposition and may be triggered by other factors. This suggests a bimodal distribution of microglial activation in Alzheimer’s trajectory as depicted in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Hypothetical model of dual peak of microglial activation in the Alzheimer’s trajectory.Top: The hypothetical model of morphological changes in microglia in Alzheimer’s disease trajectory, where ramified microglia transform to anti-inflammatory (protective) microglial phenotype and pro-inflammatory (toxic) microglial phenotypes. Bottom: The microglial activation in relation to other biomarkers detectable using positron emission tomography where two peaks of microglial activation are present in Alzheimer’s trajectory. Modified from Jack et al. (2010).

This is the first study to demonstrate that there are two peaks of microglial activation in the Alzheimer’s disease trajectory in vivo. For the first peak, significant microglial activation in the subjects with MCI at baseline is consistent with pathological studies showing that there is significant inflammation during the initial stages of the disease. For instance, the increased YKL-40, a putative indicator of inflammation, was found in preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease, indicating neuroinflammation could occur in the early stage (Craig-Schapiro et al., 2010). It has also been suggested that, in the initial stages of the disease, microglia are trying to clear amyloid and other toxic products as they accumulate (Rogers et al., 2002; Pan et al., 2011). This notion is supported by the presence of microglial cells surrounding amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease cerebral cortex, the presence of amyloid-β deposits in T cells, activated microglia and reactive astrocytes in the brains of subjects with MCI (Sastre et al., 2006). This could explain our finding of increased microglial activation in the early stages of the disease, as in subjects with MCI. It is suggested that failure of the microglia to clear amyloid leads to accumulation of amyloid. One could argue that this may be due to switching from protective to pro-inflammatory state at this stage, causing a decrease in anti-inflammatory microglial activation and, as disease advances as in Alzheimer’s disease, there is an increase in pro-inflammatory microglial activation, leading to two peaks of microglial activation. Recent studies on TREM2 further substantiate an early and late peak of microglial activation during the Alzheimer’s disease trajectory (Heslegrave et al., 2016; Piccio et al., 2016). TREM2, expressed on microglia, are believed to function in microglial activation. While previous studies have reported discrepant results for TREM2 levels in Alzheimer’s disease, recently a large number of subjects have demonstrated that the level of soluble TREM2 might be dependent on the different stages of Alzheimer’s disease, where TREM2 has a protective role and peaks during the early stage of the disease and later the levels drop as disease further progresses (Jiang et al., 2013; Suárez-Calvet et al., 2016).

A recent PET study has demonstrated a protective role for microglial activation using a TSPO marker, 18F-DPA-714, which has showed higher TSPO binding in slow decliners than fast decliners, with no difference in amyloid load (Hamelin et al., 2016). Hamelin et al. (2016) also demonstrated a positive correlation between TSPO binding and MMSE score and grey matter volume, which further indicates microglial activation may be beneficial in the early phase of the disease. Studies in later stages of Alzheimer’s disease have suggested progressive increase in microglial activation. In this study, we have demonstrated that there is an early peak of microglial activation in MCI stage, and one could speculate that in the early stages microglia are trying to prevent the damage by the protective mechanism.

While multiple studies have suggested that microglial activation is present in the early stage of Alzheimer’s disease, it is still argued whether microglial activation is beneficial or harmful to the neurons and, as recent studies suggest, it is possible that different microglial functional phenotypes could have different effects (Cunningham, 2013; Lyman et al., 2014). Currently, there is compelling evidence to indicate that microglia may change from one phenotype to another during different phases of the disease (Cai et al., 2013; Lynch, 2013). In this study, a longitudinal decline in TSPO binding was observed in subjects with MCI. This could be explained as disease advances, it is possible that protective anti-inflammatory microglial activation could become ineffective and exhausted over a period of time, resulting in predominant activation of pro-inflammatory microglia releasing multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines causing neuronal damage and neurodegeneration (Varnum and Ikezu, 2012), which leads to a second peak as we have reported in subjects with Alzheimer’s disease. On an individual basis, a majority of subjects with MCI had early increased microglial activation at baseline, and this reduced longitudinally. In one subject with MCI, there was a longitudinal increase in microglial activation (12%) and an associated reduction in amyloid deposition (5%) with an improvement in cognitive function, as the MMSE score increased from 25 to 28. Even though it is a single subject, one could speculate that this could be due to further activation of the protective anti-inflammatory phenotype which helped to clear amyloid-β in the early stage of the disease (Cai et al., 2013; Prokop et al., 2013; Zotova et al., 2013).

While 11C-(R)PK11195 PET biomarker cannot differentiate between different microglial activation (functional) states, recent studies have demonstrated the shift from the anti-inflammatory to pro-inflammatory state plays a central role in Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis, which may be triggered by changes in the micro-environment in the brain (Varnum and Ikezu, 2012; Sanchez-Guajardo et al., 2013). In the current study, we found that amyloid-positive subjects with MCI have revealed a longitudinal reduction in microglial activation during follow-up, while relatively less reduction was found in amyloid-negative subjects. This may indicate that amyloid pathology causes significant microglial activation early on in the disease process, perhaps in an attempt to clear the amyloid load. One could argue that the presence of the amyloid causes excessive glial activation in the beginning, and as disease advances, these microglia become ineffective (less activated) at an accelerated rate than those subjects who are amyloid-negative (Villemagne et al., 2013; Lim et al., 2014). Several PET studies evaluating microglia in vivo have demonstrated conflicting results, some suggesting increased microglial activation in early stages of the disease (Yasuno et al., 2012; Hamelin et al., 2016) while others found no microglial activation (Schuitemaker et al., 2013). However, none of these studies has evaluated microglial activation longitudinally using PET and selected subjects at different stages of the disease. This dual peak in a heterogeneous population could account for some of the differences in results of microglial activation in different studies. Interestingly, studies evaluating anti-inflammatory agents in Alzheimer’s disease have also produced conflicting results. One could speculate that if any anti-microglial agents are to be effective, they have to specifically target the pro-inflammatory phenotype, and hence the inconsistencies in the results.

BPM correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation between microglial activation and amyloid deposition. At follow-up, more clusters of positive correlation between microglial activation and amyloid were seen in temporoparietal lobe, which could imply that, as amyloid increases, local microglial activation is also increased and one could speculate that, as amyloid increases, microglia are trying to clear the amyloid. Microglia are key innate immune cells and it is possible that, in the process of removing the cell debris, the toxic products accumulate and damage the neurons in the vicinity (Mandrekar-Colucci and Landreth, 2010; Doens and Fernandez, 2014). In Alzheimer’s disease brain, it has been shown that plaques cause direct activation of the complement system by binding to the C1q protein in pyramidal neurons, which is significantly increased. Thus, in agreement with our previous findings, it is possible that, due to continuous toxic insult, microglia lose their beneficial property and become toxically over-activated perhaps by the unexpected complement system induced by C1q protein, which may lead to further damage to the neurons, cognitive impairment and worsening of Alzheimer’s disease (Fraser et al., 2010).

While we noticed a voxel-wise positive correlation between microglial activation and amyloid deposition, we found the level of microglial activation in subjects with MCI decreased over time. In spite of the regional reduction in microglial activation, more clusters of positive association between amyloid and microglial activation were observed at the voxel level during MCI follow-up, suggesting more microglia are specifically targeting amyloid. However, there was a group-wise deterioration of cognitive function suggesting that, as disease advances, amyloid deposition and microglial activation could play a synergistic role in accelerated neurodegeneration. This suggests that, rather than a simple direct relationship, it is more likely to imply a complex relationship between microglial activation and amyloid, potentially due to different functional microglial activation in different stages of disease.

This is a study with small numbers and cohorts followed longitudinally at different time points. A larger sample size with longer longitudinal follow-up is necessary to confirm or refute the bimodal relationship between microglial activation and amyloid that we are postulating. 11C-(R)PK11195 PET provides a relatively low signal-to-noise ratio across varying neurodegeneration. Currently, our laboratory and others have been evaluating second-generation TSPO ligands (11C-PBR28, 11C-DPA713, and 18F-GE180) with the aim of achieving better signal-to-noise ratio and discrimination of active disease states from health. However, these newer ligands are influenced by TSPO genotype and, to date, they have not been proven to be superior to 11C-(R)PK11195 PET for discriminating Alzheimer’s disease from healthy controls. The future goal is to confirm the pathological relationship between amyloid aggregation and microglial activation and to determine whether anti-microglial agents show efficacy in suppressing cell activity.

In conclusion, this is one of the first longitudinal PET studies evaluating microglial activation changes associated with MCI and Alzheimer’s disease progression, and correlating these with levels of amyloid deposition. It has revealed that, while inflammation is initially present in MCI, it diminishes over 14 months but then subsequently rises as progressing to Alzheimer’s disease. This supports the view that microglial activation is a dynamic process, and are probably undergoing constant transformation between phenotypes. We speculate that activated microglia in subjects with MCI initially adopt a protective phenotype but change to a cidal phenotype as disease progresses and amyloid clearance fails. This results in two peaks of microglial activation and suggests that anti-microglial agents may have their most beneficial effect in later stages of the disease when they target the pro-inflammatory phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Hammersmith Imanet, GE Healthcare, for the provision of radiotracers, scanning, and blood analysis equipment.

Funding

Dr Edison was funded by the Medical Research Council and now by Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). The PET scans and MRI scans were funded by the Medical Research Council and Alzheimer’s Research UK. This article presents independent research funded by Medical Research Council and Alzheimer’s Research, UK and supported by the NIHR CRF and BRC at Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. P.E. has also received grants from Alzheimer’s Research, UK, Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation, Alzheimer’s Society, UK, Novo Nordisk and GE Healthcare. D.J.B. has received research grants and non-financial support from the Medical Research Council, grants from Alzheimer’s Research Trust, during the conduct of the study; other from GE Healthcare, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Cytox, personal fees from Shire, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from GSK, Holland, personal fees from Navidea, personal fees from UCB, personal fees from Acadia, grants from Michael J Fox Foundation, grants from European Commission, outside the submitted work. A.O. and Miss Fan have nothing to disclose.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Brain online.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BP

binding potential

- BPM

Biological Parametric Mapping

- MCI

mild cognitive impairment

- SPM

statistical parametric mapping

References

- Amor S, Puentes F, Baker D, van der Valk P. Inflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology 2010; 129: 154–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AN, Pavese N, Edison P, Tai YF, Hammers A, Gerhard A. et al. A systematic comparison of kinetic modelling methods generating parametric maps for [(11)C]-(R)-PK11195. Neuroimage 2007; 36: 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Hussain MD, Yan LJ. Microglia, neuroinflammation, and beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Neurosci 2013; 124: 307–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova R, Srikanth R, Baer A, Laurienti PJ, Burdette JH, Hayasaka S. et al. Biological parametric mapping: a statistical toolbox for multimodality brain image analysis. Neuroimage 2007; 34: 137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig-Schapiro R, Perrin RJ, Roe CM, Xiong C, Carter D, Cairns NJ. et al. YKL-40: a novel prognostic fluid biomarker for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 68: 903–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham C. Microglia and neurodegeneration: the role of systemic inflammation. Glia 2013; 61: 71–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doens D, Fernandez PL. Microglia receptors and their implications in the response to amyloid beta for Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Neuroinflammation 2014; 11: 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison P, Ahmed I, Fan Z, Hinz R, Gelosa G, Ray Chaudhuri K. et al. Microglia, amyloid, and glucose metabolism in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013; 38: 938–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison P, Archer HA, Gerhard A, Hinz R, Pavese N, Turkheimer FE. et al. Microglia, amyloid, and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease: an [11C](R)PK11195-PET and [11C]PIB-PET study. Neurobiol Dis 2008; 32: 412–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Aman Y, Ahmed I, Chetelat G, Landeau B, Ray Chaudhuri K. et al. Influence of microglial activation on neuronal function in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2015a; 11: 608–21.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Okello AA, Brooks DJ, Edison P. Longitudinal influence of microglial activation and amyloid on neuronal function in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2015b; 138 (Pt 12): 3685–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DA, Pisalyaput K, Tenner AJ. C1q enhances microglial clearance of apoptotic neurons and neuronal blebs, and modulates subsequent inflammatory cytokine production. J Neurochem 2010; 112: 733–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro R, Hardy J. TREM2 and neurodegenerative disease. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1569–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro RJ, Hardy J. Alzheimer’s disease genetics: lessons to improve disease modelling. Biochem Soc Trans 2011; 39: 910–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin L, Lagarde J, Dorothee G, Leroy C, Labit M, Comley RA. et al. Early and protective microglial activation in Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective study using 18F-DPA-714 PET imaging. Brain 2016; 139 (Pt 4): 1252–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, Landreth GE, Brosseron F, Feinstein DL. et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 388–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslegrave A, Heywood W, Paterson R, Magdalinou N, Svensson J, Johansson P. et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 concentration in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2016; 11: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth P, Harold D, Jones L, Owen MJ, Williams J. Alzheimer’s disease genetics: current knowledge and future challenges. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011a; 26: 793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingworth P, Harold D, Sims R, Gerrish A, Lambert JC, Carrasquillo MM. et al. Common variants at ABCA7, MS4A6A/MS4A4E, EPHA1, CD33 and CD2AP are associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 2011b; 43: 429–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW. et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol 2010; 9: 119–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaturapatporn D, Isaac MG, McCleery J, Tabet N. Aspirin, steroidal and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 2: CD006378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T, Yu JT, Zhu XC, Tan L. TREM2 in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurobiol 2013; 48: 180–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Maruff P, Pietrzak RH, Ames D, Ellis KA, Harrington K. et al. Effect of amyloid on memory and non-memory decline from preclinical to clinical Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2014; 137: 221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman M, Lloyd DG, Ji X, Vizcaychipi MP, Ma D. Neuroinflammation: the role and consequences. Neurosci Res 2014; 79: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MA. The impact of neuroimmune changes on development of amyloid pathology; relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Immunology 2013; 141: 292–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrekar-Colucci S, Landreth GE. Microglia and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Cns Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2010; 9: 156–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello A, Koivunen J, Edison P, Archer HA, Turkheimer FE, Nagren K. et al. Conversion of amyloid positive and negative MCI to AD over 3 years: an 11C-PIB PET study. Neurology 2009; 73: 754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XD, Zhu YG, Lin N, Zhang J, Ye QY, Huang HP. et al. Microglial phagocytosis induced by fibrillar beta-amyloid is attenuated by oligomeric beta-amyloid: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 2011; 6: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccio L, Deming Y, Del-Águila JL, Ghezzi L, Holtzman DM, Fagan AM. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 is higher in Alzheimer disease and associated with mutation status. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131: 925–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokop S, Miller KR, Heppner FL. Microglia actions in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol 2013; 126: 461–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers J, Strohmeyer R, Kovelowski CJ, Li R. Microglia and inflammatory mechanisms in the clearance of amyloid beta peptide. Glia 2002; 40: 260–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Guajardo V, Barnum CJ, Tansey MG, Romero-Ramos M. Neuroimmunological processes in Parkinson’s disease and their relation to alpha-synuclein: microglia as the referee between neuronal processes and peripheral immunity. ASN Neuro 2013; 5: 113–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre M, Klockgether T, Heneka MT. Contribution of inflammatory processes to Alzheimer’s disease: molecular mechanisms. Int J Dev Neurosci 2006; 24: 167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuitemaker A, Kropholler MA, Boellaard R, van der Flier WM, Kloet RW, van der Doef TF. et al. Microglial activation in Alzheimer’s disease: an (R)-[(1)(1)C]PK11195 positron emission tomography study. Neurobiol Aging 2013; 34: 128–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidahara M, Tsoumpas C, Hammers A, Boussion N, Visvikis D, Suhara T. et al. Functional and structural synergy for resolution recovery and partial volume correction in brain PET. Neuroimage 2009; 44: 340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Calvet M, Kleinberger G, Araque Caballero MÁ, Brendel M, Rominger A, Alcolea D. et al. sTREM2 cerebrospinal fluid levels are a potential biomarker for microglia activity in early‐stage Alzheimer’s disease and associate with neuronal injury markers. EMBO Mol Med 2016; 8: 466–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer FE, Edison P, Pavese N, Roncaroli F, Anderson AN, Hammers A. et al. Reference and target region modeling of [11C]-(R)-PK11195 brain studies. J Nucl Med 2007; 48: 158–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer FE, Smith CB, Schmidt K. Estimation of the number of “true” null hypotheses in multivariate analysis of neuroimaging data. Neuroimage 2001; 13: 920–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varley J, Brooks DJ, Edison P. Imaging neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: recent advances and future directions. Alzheimers Dement 2015; 11: 1110–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum MM, Ikezu T. The classification of microglial activation phenotypes on neurodegeneration and regeneration in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2012; 60: 251–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O. et al. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 357–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Bernhardi R, Eugenin-von Bernhardi L, Eugenin J. Microglial cell dysregulation in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci 2015; 7: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuno F, Kosaka J, Ota M, Higuchi M, Ito H, Fujimura Y. et al. Increased binding of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in mild cognitive impairment-dementia converters measured by positron emission tomography with [(1)(1)C]DAA1106. Psychiatry Res 2012; 203: 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotova E, Bharambe V, Cheaveau M, Morgan W, Holmes C, Harris S. et al. Inflammatory components in human Alzheimer’s disease and after active amyloid-beta42 immunization. Brain 2013; 136 (Pt 9): 2677–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.