Why was the cohort set up?

Research on malnutrition and malaria has been conducted in the Kiang West district of The Gambia (West Africa) since 1950, initially through Professor Sir Ian McGregor’s annual anthropometric and health surveys of the rural subsistence farming community in this low- and middle-income country (LMIC) setting (described in more detail elsewhere1). With the establishment of a permanent field station by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC Keneba) in 1974, research and health provision expanded into the wider community. MRC Keneba is located in the heart of the 750-km2 district located in the Lower River Region, which until 2014 had limited road access (Figure 1). Research facilities in KW were initially set up to support nutrition studies, in particular for longitudinal studies of growth in four ‘core villages’ (with ∼ 4000 residents). Since 1989, research studies also recruited participants from the wider district. The establishment of the comprehensive demographic surveillance [Kiang West Demographic Surveillance System (KWDSS)], electronic medical record [Keneba Electronic Medical Records System (KEMReS)] and biobanking platforms (Keneba Biobank) now comprises an integrated system for research and health care provision to the whole of the Kiang West Longitudinal Population Study (KWLPS) cohort (N ∼ 14 000 across 36 villages).

Figure 1.

Map of the study area. The Kiang West district is located in the lower river division in The Gambia. Initial surveys were conducted in the core villages—Keneba, Manduar, KantongKunda and Jali (dark grey circles). The MRC Keneba field station now serves all villages in the district (light grey circles) captured by the KW Demographic Surveillance System (KWDSS). There are also two small government health centres (squares labelled M). A midwife is stationed in Jiffarong and the nearest hospital is in Bwiam (square labelled H) outside the district on the main road to the coast, respectively (for more details see Supplementary materials, available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Since 1949, this work has primarily been supported by funds from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement.

Who is in the cohort?

The population of Kiang West is predominantly of Mandinka ethnicity (Mandinka 79.9%, Fula 16.2%, Jola 2.4%, other 1.3%) living across some 36 villages. Villages are divided into compounds, where extended multi-generational families live together with an average of 16 people per compound (range 1–170). This predominantly Muslim society practises polygamy. Rural subsistence farming is the main livelihood. Income and eating patterns fluctuate strongly according to the annual farming calendar, heavily influenced by the annual rainy season (June to October). Although more than half of the Gambian adult population has not received any education, with higher proportions in rural areas, the gross enrolment ratios for lower basic (ages 7–12 years) and upper basic (ages 13–15 years) education are around 88% and 66%, respectively, with an increase in the number of girls attending school over the years; approximately half of the children not in lower basic education attend Islamic schooling.2,3

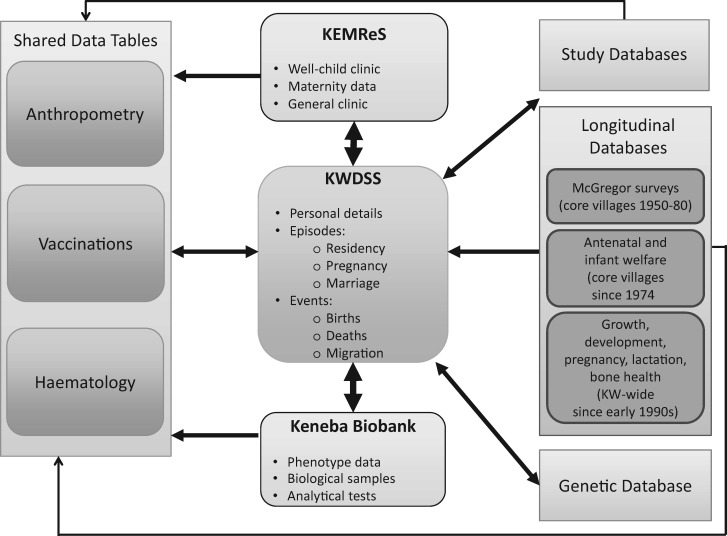

The ‘core’ villages of Keneba, Manduar, Kantong Kunda and for a limited period Jali, have been the subject of longitudinal demographic and health surveys since 1950. In 1974 and 1977 respectively, regular outpatient and antenatal clinics were established at the MRC Keneba field station to serve the medical needs of these villages. Health care provision and research studies after 1989 started to extend beyond the core villages in the wider Kiang West District (Figure 2). Since 2004, all Kiang West residents are captured by the KWDSS; this now forms the backbone of the data flow structure and participant recruitment for all MRC research studies in the region (Figure 3). In 2009, the KEMReS was launched to capture detailed morbidity data of Kiang West citizens for all primary health care contacts with the clinic at MRC Keneba. The Keneba Biobank was established in 2012. All recent and ongoing research projects are linked to one or more elements of the platforms triad KWDSS/KEMReS/KenebaBiobank. Data capture using electronic tablets has been introduced for our most recent studies in the region. Study-specific databases are not described here in detail, but we refer the reader to the references in the findings section below and our publication list via the MRC ING website [www.ing.mrc.ac.uk]. However, information on longitudinal databases (i.e. core village and other longitudinal data), as well as systematically collected data, is given in the following sections. Summary statistics for the KWLPS cohort are shown in Table 1 and also in Supplementary Figure 1 (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of time lines of data collection in Kiang West. Studies and surveys, especially those since 2000, are contained within the Kiang West Longitudinal Population Study (KWLPS) electronic databases.

Figure 3.

Database structure and data flow for the Kiang West Longitudinal Population Study (KWLPS) cohort. For further details on the KWLPS databases see Supplementary materials (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Table 1.

Summary statistics of the Kiang West Longitudinal Population Study (KWLPS) cohort in 2013 and of The Gambia national data in comparison

| Parameter | Kiang West | The Gambia | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 14 846 | 1 967 7092 | Inhabitants |

| Crude birth rate | 34.86 | 30.062 | Births per 1000 people |

| Total fertility rate | 5.50 | 3.732 | Babies per lifetime |

| Crude death rate | 6.40 | 7.172 | Per 1000 people |

| Neonatal mortality rate | 23.44 | 223 | Per 1000 births |

| Post-neonatal mortality rate | 15.63 | 123 | Per 1000 births |

| Infant mortality rate (aged < 1 year) | 39 | 343 | Per 1000 live births |

| Child mortality rate (1–4 years) | 6 | 203 | Per 1000 live 1-year-olds |

| Under-five mortality (< 5 years) | 45 | 543 | Per 1000 live births |

| Crude rate of natural increase | 28.46 | 24.49 | Per 1000 people (birth rate minus crude death rate) |

| In-migration rate | 89.86 | N/A | Per 1000 people |

| Out-migration rate | 88.91 | N/A | Per 1000 people |

| Life expectancy at birth, female | 73.46 (64.94, 81.98) | 63 (N/S)12 | Years (CI 95%) |

| Life expectancy at birth, male | 65.28 (58.71, 71.84) | 59 (N/S)12 | Years (CI 95%) |

N/A, not applicable; N/S, not specified.

How often have they been followed up?

Core village and historical data

The conduct and content of demographic and health surveys, clinics and vaccination programmes before 2004, as well as the resulting reduction in mortality, have been described in detail by Rayco-Solon and colleagues.1 Medical data at the MRC Keneba clinic were collected on paper before 2009. Data of structured child welfare clinics, vaccinations and antenatal clinics were entered into a database for those residing in the core villages since around 2000 (Figure 2). The remainder of medical data recordings for Kiang West residents beyond the core villages was not electronically transcribed before 2009.

KWDSS

The main purpose of the KWDSS is to provide reliable and up-to-date demographic data on the population of the Kiang West, to support the many research projects conducted by the MRC in the district. In particular it provides:

a common numbering system for all Kiang West residents and study subjects;

accurate dates of birth and identification of parents;

a sampling frame for study participant selection;

population structure, used to facilitate the design/assess feasibility of new studies;

residence histories for survival analyses;

and tracking of individuals’ movements, to facilitate longitudinal and follow-up studies.

Every individual who has been resident in Kiang West since 2004, and all who have taken part in our studies before that date, are assigned a unique identity number (ID), the West Kiang number (WKNO). Every compound in the district is visited once every 3 months according to a fixed schedule. The first 2 months of each cycle are dedicated to routine visits and the third is set aside to resolve discrepancies and double registrations and link the unique ID of the parents of newly registered individuals, linking district-internal migration movements and conduct quality assurance. At each visit a senior member of the compound is interviewed to provide the required information.

Since the KWDSS is used as a sampling frame within the KWLPS cohort, maintaining the integrity of the linkages within the KWDSS, and between it and other databases, is critical. In order to achieve this, we impose two basic constraints: (i) no individual can be recruited by a study or the clinic until they have been assigned a unique ID number; and (ii) no delivery can be recorded in the maternity database unless the mother has an ‘open’ pregnancy episode recorded. It is also often necessary to find the unique ID number of an individual based on limited information, but this is not always a straightforward task in a setting such as rural Gambia. For this purpose we devised a search utility, the ‘Demography Search using Bayes’ (DSUB) algorithm to search the KWDSS database for individual(s). The user may input whatever is known of the individual and the programme outputs the best matches. The KWDSS is a registered INDEPTH Network [http://www.indepth-network.org/] member centre. Additional information on the KWDSS, including the search algorithm, is given in the Supplementary materials (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

KEMReS

The primary health care clinic at the MRC Keneba field station (Figure 1) provides general health care to all Kiang West citizens who present with acute or chronic medical conditions. Around 1500 patients, excluding visitors to Kiang West, are seen each month, with seasonal variation (Supplementary Figure 2, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Children aged under 5 years attend the clinic in Keneba about four times per year, depending on the village of origin within the district and transport availability. Emergency presentations are seen 24 h per day. General, child welfare, antenatal/postnatal and non-communicable disease (NCD) clinics are run weekly. An observation room allows stabilization of patients, but full inpatient facilities are not available. Patients requiring treatment at a secondary/tertiary medical facility get transported to either the clinic at MRC Fajara or the Edward Francis Small Teaching Hospital (formerly the Royal Victoria Teaching Hospital) in Banjul, both 2–3 h by road.

KEMReS started recording patient attendances in December 2009 and was designed to capture clinical data of all presentations at the clinic at MRC Keneba across all age groups, to: understand in depth the epidemiology of communicable and non-communicable diseases; support ongoing research projects; and improve clinical care for the population. The database also incorporates data on regular child welfare clinics (for those aged < 2 years) and vaccinations. Electronic capture of antenatal/postnatal information was added to KEMReS in 2013. KEMReS as a platform in conjunction with the other databases can provide details on adverse events and/or morbidity data as outcome measures for clinical trials in the district. For more detail on the KEMReS set-up access, see Supplementary materials (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Keneba Biobank

The Keneba Biobank was initiated in May 2012, as a platform for genetic studies and the collection of biological samples and simple phenotypic measures for all consenting individuals captured by the KWDSS. A custom-designed database and sample tracking system was introduced, which is used for all Biobank-related processes. The Keneba Biobank is currently in its first round, with recruitment standing at > 9000 participants to date. To ensure an even distribution of recruitment by season, the region was block randomized into 10 sectors of roughly equal size comprising either a single village or several smaller villages. Every 2 weeks, recruitment moves to a different sector, with all sampling and most measures conducted in the field. Participants are visited in the early morning to obtain age group-specific data and (fasted) biological samples. Clinical referral criteria were defined to identify urgent referrals (malaria or severe high blood pressure) observed during the field visit. Affected participants, as well as those who report feeling sick, are brought back to the MRC Keneba clinic on the same day for evaluation by a clinician. Non-urgent referrals (high glucose level, high blood pressure, anaemia) are identified via a search function within the Keneba Biobank database, and cases are called within a few days for re-testing and clinical evaluation during regular clinics (e.g. the weekly NCD clinic).

The Keneba Biobank is part of the LMIC Biobank and Cohort Network (BCNet), [http://bcnet.iarc.fr/].4 Additional information on the Keneba Biobank is given in the Supplementary materials (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

What has been measured?

Core village and historical data

The KWLPS database comprises computerized records of all Kiang West residents (N ∼ 14 000). For core village residents (N ∼ 4000) these date back to 1950,1 representing life-course longitudinal nutritional and health phenotypes, particularly relating to anthropometry/growth and maternal health. The consistent and longitudinal recording of the following measures were introduced over time.

Since 1949: exact date of birth and parents’ IDs.

Since 1980: birth (weight, length, gestational age, delivery date); growth (weight, height, mid upper-arm circumference, head circumference) for children on up to 12 occasions before 2 years of age and less frequently thereafter); demographics (parents’ IDs), pregnancy outcomes and reproductive histories; records of self-referrals to clinic; and outcome measures from numerous specific studies.

Since 1990: most studies include anthropometric measurements, blood pressure, dietary and lifestyle information and blood and urine samples. In selected study groups, detailed data on bone mineral content and density, bone dimensions and more recently bone age, and muscle force and power have been measured.

Since 1996: vaccinations.

Please note that details of study databases are not described here; further information can be found in the findings section below and via the MRC ING publication list [www.ing.mrc.ac.uk].

KWDSS

During each KWDSS round, the following information is captured: migration movements, into and out of the compound (both internal and external, including contact details for those leaving the district), births and deaths, pregnancies (to avoid missing infants who die during the neonatal period), marriages and the names or unique IDs of the parents of all newborns or new arrivals. Details of husbands of married women are mostly recorded to identify the children’s fathers. All changes in status for each Kiang West citizen are captured.

An important feature of the KWDSS is that we allow data to be recorded from other sources. For instance, births and pregnancies may be derived from the maternity arm of KEMReS. Similarly, information is rectified when patients present to the general MRC Keneba clinic. This ensures that dates of birth are recorded accurately and up-to-date data on individuals are available from a single database table without needing to wait for the next KWDSS round. The two main types of data tables used by KWDSS are ‘constant’ and ‘episode’ (for details see Supplementary materials, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). Briefly, constant tables are mostly used to record unchanging data such as name or date of birth. Episode tables record details of time intervals, e.g. the residency of an individual living in a particular compound.

KEMReS

KEMReS records a set of data entry fields for each stage during a patient encounter based on well-known clinical examination routines [Supplementary Figure 3 (available as Supplementary data at IJE online) and Table 25]. Recorded information includes data on anthropometry, vital signs, symptom history and examination findings, laboratory investigations, diagnoses and prescriptions provided. Data are stored with two specified ranges according to age: (i) normal range; and (ii) possible range. An alert for the clinician/nurse appears for values out of the normal range, to address the finding clinically. A full data set at each stage needs to be entered before the patient can proceed. This ensures the accuracy and completeness of data collected at each clinic visit.

Table 2.

Data collected in the Keneba Electronic Medical Records System (KEMReS) during each patient encounter

| Data collection stage | General description of data stored |

|---|---|

| Reception |

|

| Triage |

|

| Doctor/nurse |

|

| Midwives |

|

| Laboratory |

|

| Dispensary |

|

| Check-out |

|

Past encounters and medical history are stored and updated with each patient encounter to aid clinical assessments and medical decisions. Diagnoses are recorded using the WHO ICD-10 coding system.6 Diagnoses also include: ‘Well with a complaint’; ‘Well without a complaint’; and ‘Unknown diagnosis’. A free text entry can be used to describe possible diagnoses further. KEMReS is not a clinical decision support system, although this can relatively easily be added. However, KEMReS consists of a number of user interfaces with several functionalities including clinical care reports, referral letters, management reports and medication dispensary reports. Furthermore, alerts are set for due vaccinations and drug prescriptions, to be in line with international guidelines on patient management7.

Keneba Biobank

Table 3 shows a summary of data and samples collected as part of the Keneba Biobank by trained staff using standardized operating procedures. Briefly, agegroup-specific data and samples collected comprise: biological samples (venous blood, urine); questionnaire; anthropometry, body composition based on bioelectrical impedance (using population-specific equations8); and blood pressure. Biological sample processing and a limited number of analytical tests are conducted on fresh specimens at the MRC Keneba field station. Analytical tests conducted comprise fasting glucose, malaria, zinc protoporphyrin (discontinued in 2014) and full blood count. Samples processing involves the separation of blood fractions (serum, plasma, washed red blood cells), treatment of urine and DNA extraction; all samples are split into several aliquots and stored in 2D-barcoded microtubes at −70°C within 2–4 h of collection.

Table 3.

Data and samples collected as part of the Keneba Biobank

| < 5-year-olds | 5–18 year olds | 18-year-olds | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire | N/A | N/A | Education, assets, medication for diabetes and hypertension received outside the district |

| Phenotypes | Weight, height, skinfold thickness, head circumference, mid upper-arm circumference | Weight, height, body composition, blood pressure | Weight, height, body composition, blood pressure |

| Field and laboratory analyses | Malaria test, ZNPP, full blood count | ZNPP, glucose, blood pressure, full blood count | ZNPP, glucose, blood pressure, full blood count |

| Biological samples collected | Unfasted blood (4.0 ml EDTA, 1.2 ml serum) | Fasted blood (4.9 ml EDTA, 1.2 ml LH, 4.5 ml serum) and ∼ 3 ml urine | Fasted blood (4.9 ml EDTA, 1.2 ml LH, 4.5 ml serum) and ∼ 3 ml urine |

| Biological sample aliquots banked | Whole blood, red blood cells, plasma, serum, DNA | Whole blood, red blood cells, plasma, serum, DNA; urine (spun, unspun, acidified) | Whole blood, red blood cells, plasma, serum, DNA, urine (spun, unspun, acidified) |

Weight in kg to the nearest 10 g; height, head circumference and mid upper-arm circumference (MUAC) to the nearest 0.1 cm; body composition by Tanita BC-418 MA analyser; blood pressure Omron 705-CPII; fasting glucose Accu Check (Roche Diagnostics); malaria rapid test (Standard Diagnostics); zinc protoporphyrin (ZnPP) by haematoflurometer (Aviv Biomedical); full blood count by Medonic M-series 3-part haematology analyser (Boule Medical); acidified urine samples treated with concentrated hydrogen chloride; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; LH, lithium-heparin.

Ethical considerations

All studies and data collections in Kiang West are presented to and approved by the MRC Unit The Gambia Scientific Committee (SCC) and joint Gambian Government/MRC Unit The Gambia Ethics committee, which is overseen by the ethics board of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). For research studies, all participants and/or legal guardians provide written, informed consent.

What has it found? Key findings and publications

Summary statistics of the KWLPS cohort compared with national data from The Gambia are shown in Table 1. It is noteworthy that mortality rates have improved dramatically over the past decades,1 with higher life expectancy in women and greater reductions in crude and child mortality rates seen in Kiang West than elsewhere in The Gambia.2,9 Differences are likely due to higher standards of clinical services children and women receive, including regular child welfare clinics and ante- and postnatal follow-up in Kiang West, compared with other regions. Slightly higher neonatal, post-neonatal and infant mortality rates in Kiang West compared with national data probably relate to the better capture of data on deaths, since almost all pregnancies are monitored and their outcomes recorded. Table 4 shows the 10 most common medical diagnoses by age group based on ICD-10 coding.6 Morbidity patterns are similar to previous studies in the sub-region, with around 30% related to respiratory illness.10 In those over 50 years old, NCDs form a large part of clinic presentations. Prevalence of malaria across the whole of the Gambian population has decreased recently11 and, particularly in those under 10 years of age, malaria represents now fewer than 2% of all clinic presentations.

Table 4.

Ten most common clinical diagnoses made per age group between January 2010 and July 2014 at the MRC Keneba clinic

| Age group | < 1 years | 1–4 years | 5-9 years | 10–14 years | 15–19 years | 20–49 years | >50 years | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of clinic visits per age group (% of total overall)a | 9712 (10) | 16360 (17) | 8544 (9) | 9206 (10) | 7730 (8) | 24951 (27) | 17344 (18) | ||||||||||||||

| Total number of diagnoses / reasons for visit per age groupb | 13058 | 21254 | 9828 | 10489 | 8913 | 30464 | 23890 | ||||||||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||||||

| 10 most common diagnoses / reasons for visit per age group | Common cold | 3031 | 23 | Common cold | 5379 | 25 | Common cold | 1973 | 20 | Common cold | 2005 | 19 | Common cold | 1443 | 16 | Common cold | 2733 | 9 | Hypertension | 6430 | 27 |

| Routine child examination | 1547 | 12 | Viral gastroenteritis | 1612 | 8 | Skin infection | 659 | 7 | Abdominal pain | 886 | 8 | Abdominal pain | 761 | 9 | Unknown diagnosis | 1906 | 6 | Follow up examination | 1871 | 8 | |

| Viral gastroenteritis | 1537 | 12 | Pneumonia | 1299 | 6 | Abdominal pain | 624 | 6 | Headache | 679 | 6 | Unknown diagnosis | 430 | 5 | Headache | 1809 | 6 | Common cold | 1465 | 6 | |

| Pneumonia | 908 | 7 | Follow up examination | 1215 | 6 | Pneumonia | 417 | 4 | Unknown diagnosis | 498 | 5 | Headache | 326 | 4 | Hypertension | 1647 | 5 | Backache | 1248 | 5 | |

| Follow up examination | 901 | 7 | Intestinal helminthiasis | 1093 | 5 | Unknown diagnosis | 388 | 4 | Skin infection | 471 | 4 | Local skin infection | 297 | 3 | Backache | 1630 | 5 | Unknown diagnosis | 983 | 4 | |

| Well without complaint | 492 | 4 | Local skin infection | 1061 | 5 | Headache | 366 | 4 | Conjunctivitis | 316 | 3 | Toothache | 240 | 3 | Abdominal pain | 1405 | 5 | Headache | 893 | 4 | |

| Conjunctivitis | 447 | 3 | Cutaneous abscess | 926 | 4 | Conjunctivitis | 338 | 3 | Injury | 300 | 3 | Tonsillitis | 218 | 2 | Urinary tract infection | 1137 | 4 | Unspecified pain | 768 | 3 | |

| Cutaneous abscess | 376 | 3 | Conjunctivitis | 703 | 3 | Follow up examination | 316 | 3 | Tonsillitis | 281 | 3 | Unspecified pain | 206 | 2 | Follow up examination | 1077 | 4 | Old age | 693 | 3 | |

| Local skin infection | 364 | 3 | Routine child examination | 605 | 3 | Injury | 275 | 3 | Sickle-cell disorders | 275 | 3 | Dysmenorrhoea | 198 | 2 | Unspecified pain | 1064 | 3 | Pneumonia | 692 | 3 | |

| Marasmus | 330 | 3 | Impetigo | 605 | 3 | Intestinal helminthiasis | 242 | 2 | Plasmodium falciparum malaria | 265 | 3 | Plasmodium falciparum malaria | 195 | 2 | Epigastric pain | 945 | 3 | Arthritis | 583 | 2 | |

Diagnoses are classified according to the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and stored in KEMReS using the ICD-10 coding system.9 The diagnoses include follow-up examinations (ICD-10 code Z09) and routine child welfare clinic examinations (ICD-10 code 700.1).

aOverall there were 93 847 clinic visits.

bA total overall of 104 839 diagnoses were made.

There are numerous publications describing the vast body of research conducted in the KWLPS cohort since the early 1950s, too many to list and describe. However, the key findings and publications can be broadly described under the categories of: (i) secular trends; (ii) major research findings; and (iii) recent developments. A short summary of these is given below; for a comprehensive list of references over recent years, see our publication list via the MRC ING website [www.ing.mrc.ac.uk].

Reports on secular trends describe declining mortality trends;1,12,13 intergenerational and demographic transition effects on growth14,15 and survival;16 reductions in diarrhoea rates;17 declining malaria rates.11

Major research findings include: insights into season of birth or conception effects on mortality;18 immune outcomes19 and DNA methylation;20 effects of pregnancy supplementation on low birthweight;21 increased understanding of growth faltering; identification of critical windows beyond the ‘first 1000 days’ for possible nutritional interventions to address stunting;22 lack of anticipated benefits of calcium supplementation in children and pregnant mothers with a very low calcium intake, with identification of unexpected, possibly adverse, long-term skeletal effects;23–25 the use of MUAC to identify infants at increased risk of death in LMIC;26 and the efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination after 24 years of follow-up.27

More recent developments with respect to the KWLPS cohort are covered by the following publications on: early nutrition and immune development via a birth cohort followed up since 2010 (the ENID trial);28 life course nutrition and health, including immune/inflammatory outcomes29 and cognitive development;30 the role of the iron-hepcidin axis in infection;31,32 and seasonal effects on blood cell composition.33

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

Strengths

Stable, well-characterized and ‘research-friendly’ population in rural sub-Saharan Africa of highly homogeneous ethnicity. Exceptional long-term relationship between population and MRC maintained through high levels of communication between MRC staff and villages and with great care taken to ensure research ethics.

Computerized records of all Kiang West residents, some of which date back to 1950, representing a unique level of life-course nutritional and health phenotypes including: birth anthropometry and details of mother's health and nutritional status in pregnancy; detailed serial postnatal anthropometry; active health surveillance at child welfare clinics from from birth to 24 months; records of self-referrals to clinic thereafter; reproductive histories; and outcome measures from numerous specific studies.

A setting that facilitates research on the complex relationships between diet, health and survival in an environment where infectious diseases still play a major role in mediating population health, e.g. seasonal influences.

Integrated demographic surveillance and clinical and biobank research platforms with standardized variable measurements using a unique identification number per person.

Detailed pedigree records facilitating research across multiple generations.

Custom-designed framework for KWDSS, KEMReS and Keneba Biobank databases with: user-friendly interface for use by low-information technology (IT)-skilled health professionals, laboratory and field staff; coded data rather than free text; and lists facilitating ease of data management, with clear patient/participant flow limiting missing data.

Automated processes including the generation of consent and call lists; collection and logging of participant information on basic demographics, phenotypes and laboratory tests; collection, logging and tracking logging of biological samples.

The majority of research platforms and ongoing studies now work on the basis of live/current direct data entry, thereby reducing the possibility of data errors.

Large repository of banked biological samples.

Established procedure for access to samples and data via KDSG and SCC/EC application (see below).

Good database and IT support.

Weaknesses

The size of the total population of Kiang West (N ∼ 14000) is limiting for the study of, for example, rare diseases, diseases occurring infrequently in this population or in sub-groups such as women who have never been pregnant, and there is a risk of ‘over studying’.

The KWDSS system yields useful background data on the demographic status and changes in the area, although the population size is insufficient for some aspects of demographic research.

The majority of longitudinal data are restricted to residents of the core villages (N ∼ 4000), with Kiang West-wide (N ∼ 14000) data collections being more recent.

There is some bias regarding the age-sex distribution between the ages of 20 and 50, due to (temporary) outmigration to urban areas for work (see Supplementary Figure 1, available as Supplementary data at IJE online). However, we increasingly conduct studies and follow-ups outside the district.

Although the mortality overall in the Kiang West district is lower than the country average, the morbidity profile is comparable across The Gambia (see Tables 1 and 3).9

Can I get hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

Access permission for collaborators is regulated via one or more of the following: the principal investigator of platforms/research studies; the head of MRC KenebaField Station; or head of MRC ING. Further details can be found via the MRC International Nutrition Group website [www.ing.mrc.ac.uk]. Access is controlled via the Keneba Database Steering Group (KDSG) and/or applications to joint the Gambia Government/MRC Ethics Committee (SCC/EC).

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Funding

We thank all funders who have supported individual researchers and studies, as well as the infrastructure and research conducted out of MRC Keneba; major funding was received from the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID), under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement (current grants are MC-A760-5QX00, U105960371 and U123261351).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank several generations of residents of the villages of Kiang West, The Gambia, for their past and continued participation since 1950. Thanks are also due to past and present staff at MRC Keneba, too many to name individually, who were and are involved in the collection and processing of data and samples over many decades. To many researchers working at MRC Keneba over the years, who have also contributed to the wealth of data and development of research platforms over time, many thanks.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Rayco-Solon P, Moore SE, Fulford AJ, Prentice AM. Fifty-year mortality trends in three rural African villages. Trop Med Int Health 2004;9:1151–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United States Central Intelligence Agency. The Gambia, World Fact Book. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/ga.html (21 July 2015, date last accessed).

- 3. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The Gambia Education Country Status Report. 2011. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002152/215246e.pdf.

- 4. Mendy M, Caboux E, Sylla BS, Dillner J, Chinquee J, Wild C. Infrastructure and Facilities for Human Biobanking in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Situation Analysis. Pathobiology 2015;81:252–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munro J, Campbell I. Macleod’s Clinical Examination. 10th edn Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (ICD). 1990. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ (21 July 2015, date last accessed).

- 7. British National Formulary. London: BMJ Publishing Group; 2009.

- 8. Prins M, Hawkesworth S, Wright A et al. Use of bioelectrical impedance analysis to assess body composition in rural Gambian children. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:1065–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization. Gambia. http://www.who.int/countries/gmb/en/ (21 July 2015, date last accessed).

- 10. Risk R, Naismith H, Burnett A, Moore SE, Cham M, Unger S. Rational prescribing in paediatrics in a resource-limited setting. Arch Dis Child 2013;503–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ceesay S, Casals-Pascual C, Erskine J et al. Changes in malaria indices between 1999 and 2007 in The Gambia: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 2008;372:1545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McGregor I, Rahman A, Thompson B, Billewicz W, Thompson A. The growth of young children in a Gambian village. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1968;62:341–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lamb W, Foord F, Lamb C, Whitehead R. Changes in maternal and child mortality rates in three isolated Gambian villages over ten years. Lancet 1984;2:912–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Billewicz W, McGregor I. A birth-to-maturity longitudinal study of heights and weights in two West African (Gambian) villages, 1951-1975. Ann Hum Biol 1982;9:309–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Courtiol A, Rickard I, Lummaa V, Prentice A, Fulford A. The Demographic Transition Influences Variance in Fitness and Selection on Height and BMI in Rural Gambia. Curr Biol.2013;23:884–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sear R, Mace R, McGregor I. Maternal grandmothers improve nutritional status and survival of children in rural Gambia. Proc Biol Sci 2000;267:1641–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poskitt EM, Cole TJ, Whitehead RG. Less diarrhoea but no change in growth: 15 years’ data from three Gambian villages. Arch Dis Child 1999;80:115–19; discussion 119–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moore SE, Cole TJ, Poskitt EM et al. Season of birth predicts mortality in rural Gambia. Nature 1997;388:434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore SE, Richards AA, Goldblatt D, Ashton L, Szu SC, Prentice AM. Early-life and contemporaneous nutritional and environmental predictors of antibody response to vaccination in young Gambian adults. Vaccine 2012;30:4842–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dominguez-Salas P, Moore SE, Baker MS et al. Maternal nutrition at conception modulates DNA methylation of human metastable epialleles. Nat Commun 2014;5:3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prentice AM, Cole J, Foord A, Lamb H, Whitehead R. Increased birthweigh after prenatal dietary supplementation of rural African women. Am J Clin Nutr 1987;46:912–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Prentice AM, Moore SE, Fulford AJ. Growth faltering in low-income countries. World Rev Nutr Diet 2013;106:90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prentice A, Dibba B, Sawo Y, Cole TJ. The effect of prepubertal calcium carbonate supplementation on the age of peak height velocity in Gambian adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;96:1042–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jarjou LM, Sawo Y, Goldberg GR, Laskey MA, Cole TJ, Prentice A. Unexpected long-term effects of calcium supplementation in pregnancy on maternal bone outcomes in women with a low calcium intake: a follow-up study. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;98:723–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ward K, Cole TJ, Laskey MA et al. The Effect of Prepubertal Calcium Carbonate Supplementation on Skeletal Development in Gambian Boys—A 12-Year Follow-Up Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:3169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mwangome MK, Fegan G, Fulford T, Prentice AM, Berkley J. Mid-upper arm circumference at age of routine infant vaccination to identify infants at elevated risk of death: a retrospective cohort study in the Gambia. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:887–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mendy M, Peterson I, Hossin S et al. Observational Study of Vaccine Efficacy 24 Years after the Start of Hepatitis B Vaccination in Two Gambian Villages: No Need for a Booster Dose. PLoS One 2013;8:e58029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moore SE, Fulford AJ, Darboe MK, Jobarteh ML, Jarjou LM, Prentice AM. A randomized trial to investigate the effects of pre-natal and infant nutritional supplementation on infant immune development in rural Gambia: the ENID trial: Early Nutrition and Immune Development. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Richards A, Fulford AJ, Prentice AM, Moore SE. Birth weight, season of birth and postnatal growth do not predict levels of systemic inflammation in gambian adults. Am J Hum Biol 2013;25:457–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alderman H, Hawkesworth S, Lundberg M, Tasneem A, Mark H, Moore SE. Supplemental feeding during pregnancy compared with maternal supplementation during lactation does not affect schooling and cognitive development through late adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99:122–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Atkinson SH, Armitage AE, Khandwala S et al. Combinatorial effects of malaria season, iron deficiency, and inflammation determine plasma hepcidin concentration in African children. Blood 2014;123:3221–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drakesmith H, Prentice AM. Hepcidin and the iron-infection axis. Science 2012;338:768–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dopico XXC, Evangelou M, Ferreira RCR et al. Widespread seasonal gene expression reveals annual differences in human immunity and physiology. Nat Commun 2015;6:7000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.