Abstract

Background

Neonatal mortality is unacceptably high in most low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). In these countries, where access to emergency obstetric services is limited, antenatal care (ANC) utilization offers improved maternal health and birth outcomes. However, evidence for this is scanty and mixed. We explored the association between attendance for ANC and survival of neonates in 57 LMICs.

Methods

Employing standardized protocols to ensure comparison across countries, we used nationally representative cross-sectional data from 57 LMICs (N = 464 728) to investigate the association between ANC visits and neonatal mortality. Cox proportional hazards multivariable regression models and meta-regression analysis were used to analyse pooled data from the countries. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to describe the patterns of neonatal survival in each region.

Results

After adjusting for potential confounding factors, we found 55% lower risk of neonatal mortality [hazard ratio (HR) 0.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.42–0.48] among women who met both WHO recommendations for ANC (first visit within the first trimester and at least four visits during pregnancy) in pooled analysis. Furthermore, meta-analysis of country-level risk shows 32% lower risk of neonatal mortality (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.61–0.75) among those who met at least one WHO recommendation. In addition, ANC attendance was associated with lower neonatal mortality in all the regions except in the Middle East and North Africa.

Conclusions

ANC attendance is protective against neonatal mortality in the LMICs studied, although differences exist across countries and regions. Increasing ANC visits, along with other known effective interventions, can improve neonatal survival in these countries.

Keywords: Survival analysis, neonatal mortality, antenatal care, low- and middle-income countries

Introduction

Goal 4 of the world’s just-ended developmental agenda, the millennium development goals (MDGs), focused on reduction in child mortality.1 As a target, goal 4 aimed at reducing under-5 mortality by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015. The MDGs agenda has contributed to a remarkable reduction in under-5 mortality globally.2 As a result, the global number of deaths of under-5 children has declined from 12.7 million in 1990 to 6 million in 2015, although the number of births has increased over the period. This decline is not only in terms of absolute numbers but also in mortality rates for children in this age group. These have declined, over the 25-year period by more than 50%, from 90 per 1000 live births to 43 per 1000 live births.2 Although significant achievements were seen in under-5 mortality, neonatal mortality, which is a main component of the under-5 mortality, has not seen a significant reduction over the same period. This has resulted in an increase in the proportion of neonatal mortality within the under-5 deaths over the two and a half decades. In 1990, neonatal mortality was 37% of under-5 mortality, and by 2012, the figure rose to 44%: thus a deficit of 2.9 million neonatal deaths globally.3,4 Concerted effort is needed to reverse these trends in order to improve overall child survival, particularly, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where the burden of neonatal mortality is highest.2–4

Neonatal mortality also contributes to the inequalities in health between high-income and low-income countries.5,6 Neonatal mortality remains unacceptably high in most LMICs and the highest is in sub-Saharan Africa.7,8 According to a study by Lawn et al.,4 there is a lag of about 100 years in neonatal survival between African countries on the one hand, and Europe and North America on the other. Overall, the slow progress made towards addressing neonatal mortality has led to renewed commitments to tackling the challenge. The sustainable development goals (SDGs) are one of such commitments which open a new era to tackle the unfinished agenda of the MDGs as well as other emerging social, developmental and global health challenges. The SDG 3 target 3.2 aims at reducing neonatal mortality to 12 per 1000 live births by the year 2030.9 Other important renewed commitments include the Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP) which seeks to end preventable stillbirth and newborn death.3 Data from LMICs are critical in forming intervention and tracking progress towards achieving these goals.

Antenatal care (ANC) offers pregnant women an opportunity to access preventive care. In LMICs where access to emergency obstetric services is limited, ANC presents a viable option for pregnant women to be screened for potential risks during pregnancy or delivery. It also provides an opportunity for treatment and health education including nutritional advice and interventions about risky behaviour such as smoking and alcohol cessation programmes. A few studies have investigated the effect of ANC utilization on birth outcomes, particularly on neonatal mortality.10–13 Their evidence is inconclusive; whereas some found ANC utilization, including the number of visits, to be associated with reduced risk of neonatal mortality,10,13 others found adverse or no relations between ANC utilization and birth outcomes. Hollowell et al.,11 conducting a systematic review of the association between ANC and infant and neonatal mortality in high-income countries, concluded that there was insufficient evidence that ANC interventions reduced neonatal or infant mortality in vulnerable populations. Dowswell et al.14 on the other hand, in a recent systematic review of alternative ANC packages for low-risk pregnant women, found that in LMICs in particular, a reduced number of ANC visits was associated with higher perinatal mortality. However, no such evidence was found for those in high-income countries nor for other child health outcomes. For women in LMICs, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least four ANC visits for normal pregnancy, and the first visit is recommended to be within the first 3 months of conception.15 Despite these recommendations, studies have reported low ANC coverage among women in LMICs.13,16 There is a need for evidence regarding the benefits of ANC utilization on important health outcomes, to support interventions which are geared towards increasing ANC utilization in particular and improving maternal, neonatal and child health in general. Comparable national representative data from LMICs, investigating this relationship, would shed light on this. A systematic search of the literature revealed that no study using comparable data has investigated the association between ANC utilization and neonatal mortality in many LMICs. Our study aimed to investigate whether ANC attendance improves neonatal survival in LMICs. We were also interested in looking at the regional differences in neonatal survival.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was granted from the relevant institutions in the various countries and respondents gave written consent in all the countries. Participants gave consent for the data to be used for publication.

Data source

We used nationally representative cross-sectional data from 57 LMICs, collected from 2005 to 2015, in the most recent Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). The DHS uses a standardized questionnaire and methodology for data collection in order to facilitate international comparison. Details of the DHS are published elsewhere [http://www.dhsprogram.com/data/data-collection.cfm]. In our analysis we used ‘Birth record’ files published by the DHS. Permission to use the data was granted by Measure DHS. The data were publicly available and no further permission from the respective countries was required for their use.

Study population

Data were collected on the outcome of the most recent live birth within 3 years preceding the survey for each woman of reproductive age 15–49 years (N = 464 728). In Bangladesh, Egypt, Jordan, Maldives and Pakistan, the sample was collected among ever-married women as opposed to all women (both ever-married and other women) in the other countries included.

The 57 countries were grouped into six regions modelled on the WHO classification of regions. Out of 57 countries, 33 (63%) were in Africa, four were in East Asia & Pacific (6.9%), six were in Europe & Central Asia (2.0%), seven were in Latin America & Caribbean (9.5%), two were in Middle East & North Africa (4.6%) and five were in South Asia (13.5%). The full list of countries and surveys is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of the number of antenatal care (ANC) visits and the timing of the start of the first ANC visits by country and region

| Country | N a | Number of ANC visits |

Timing of first ANC visits (months) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No care | 1 visit | 2–3 visits | 4+ visits | < 4 | 4–5 | 6–7 | 8+ | Median months | ||

| Africa | ||||||||||

| Benin (2011–12) | 6640 | 11.6 | 2.4 | 23.1 | 58.3 | 48.3 | 27.5 | 6.7 | 4.7 | 3.8 |

| Burkina Faso (2010) | 8320 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 58.4 | 33.1 | 40.6 | 39.9 | 14.0 | 1.1 | 4.3 |

| Burundi (2010) | 4251 | 0.9 | 3.5 | 61.8 | 33.6 | 20.4 | 44.2 | 31.9 | 2.3 | 5.3 |

| Cameroon (2011) | 6145 | 15.0 | 2.3 | 21.1 | 60.7 | 33.1 | 35.4 | 14.8 | 1.2 | 4.5 |

| Chad (2014–15) | 8984 | 34.3 | 3.4 | 28.8 | 31.3 | 28.9 | 26.7 | 8.0 | 0.8 | 4.2 |

| Comoros (2012) | 1428 | 6.6 | 3.7 | 26.5 | 49.2 | 57.2 | 23.5 | 7.9 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

| Congo (2011–12) | 4560 | 7.2 | 0.8 | 14.2 | 77.2 | 43.6 | 39.5 | 9.4 | 0.3 | 4.1 |

| Congo DR (2013–14) | 9349 | 9.9 | 3.8 | 38.5 | 47.2 | 16.7 | 40.4 | 29.7 | 2.8 | 5.4 |

| Cote d'Ivoire (2011–12) | 4055 | 7.2 | 9.8 | 38.9 | 43.3 | 29.0 | 34.4 | 25.6 | 3.2 | 5.0 |

| Ethiopia (2011) | 5991 | 57.8 | 5.1 | 19.1 | 17.8 | 10.2 | 16.2 | 12.2 | 3.3 | 5.3 |

| Gabon (2012) | 2751 | 4.9 | 0.6 | 15.9 | 77.2 | 61.2 | 26.6 | 6.6 | 0.4 | 3.6 |

| Ghana (2014) | 3108 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 9.0 | 86.2 | 62.1 | 28.1 | 6.2 | 0.6 | 3.6 |

| Guinea (2012) | 3868 | 12.8 | 4.4 | 26.2 | 56.3 | 40.1 | 30.5 | 14.8 | 1.8 | 4.2 |

| Kenya (2014) | 10350 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 36.4 | 55.9 | 19.7 | 41.1 | 32.1 | 2.9 | 5.4 |

| Lesotho (2014) | 1900 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 20.1 | 73.3 | 40.6 | 33.7 | 18.2 | 2.6 | 4.4 |

| Liberia (2013) | 3429 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 14.7 | 77.6 | 66.7 | 23.4 | 6.0 | 0.8 | 3.3 |

| Madagascar (2008–09) | 6484 | 9.6 | 4.0 | 38.3 | 47.2 | 25.5 | 42.4 | 19.7 | 1.8 | 4.8 |

| Malawi (2010) | 10668 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 51.3 | 44.2 | 12.4 | 48.0 | 35.8 | 2.0 | 5.6 |

| Mali (2012–13) | 5340 | 24.8 | 5.3 | 28.2 | 40.9 | 34.0 | 26.5 | 11.5 | 2.6 | 4.2 |

| Mozambique (2011) | 6381 | 9.1 | 4.8 | 35.7 | 49.5 | 12.7 | 46.3 | 29.0 | 2.5 | 5.5 |

| Namibia (2013) | 2127 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 10.6 | 62.4 | 41.5 | 38.8 | 14.3 | 1.5 | 4.3 |

| Niger (2012) | 6781 | 13.2 | 6.2 | 46.9 | 33.2 | 22.0 | 40.4 | 22.1 | 1.9 | 5.0 |

| Nigeria (2013) | 16178 | 33.7 | 1.9 | 10.7 | 51.0 | 17.6 | 29.8 | 16.7 | 1.5 | 5.0 |

| Rwanda (2014–15) | 4512 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 51.7 | 44.3 | 56.0 | 30.9 | 10.8 | 1.4 | 3.9 |

| Sao Tome (2008–09) | 965 | 0.7 | 4.6 | 15.7 | 71.8 | 49.7 | 30.9 | 12.7 | 1.4 | 3.9 |

| Senegal (2014) | 6635 | 2.8 | 5.9 | 43.4 | 47.1 | 57.8 | 27.8 | 9.4 | 1.3 | 3.6 |

| Sierra Leone (2013) | 5689 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 9.0 | 75.8 | 44.7 | 41.9 | 9.8 | 0.7 | 4.1 |

| Swaziland (2006–07) | 1535 | 2.8 | 1.0 | 15.3 | 78.6 | 23.8 | 48.1 | 23.5 | 1.4 | 5.1 |

| Tanzania (2010) | 4316 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 54.0 | 39.8 | 18.6 | 49.0 | 28.0 | 2.0 | 5.2 |

| Togo (2013–14) | 3699 | 7.1 | 3.3 | 32.9 | 56.4 | 27.0 | 41.9 | 21.4 | 2.5 | 4.9 |

| Uganda (2011) | 3981 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 43.0 | 47.2 | 20.7 | 42.7 | 29.1 | 3.1 | 5.2 |

| Zambia (2013–14) | 7044 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 41.6 | 54.1 | 24.4 | 54.3 | 18.4 | 1.1 | 4.8 |

| Zimbabwe (2010–11) | 3300 | 11.3 | 3.0 | 22.7 | 61.9 | 17.5 | 38.8 | 27.0 | 5.3 | 5.4 |

| Africa pooled | 180759 | 12.4 | 3.4 | 32.8 | 51.4 | 36.4 | 34.9 | 16.8 | 1.9 | 4.5 |

| East Asia & Pacific | ||||||||||

| Cambodia (2014) | 4107 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 16.7 | 75.6 | 79.2 | 12.7 | 3.7 | 0.4 | 2.5 |

| Indonesia (2012) | 9699 | 3.0 | 1.6 | 7.3 | 87.4 | 79.8 | 12.0 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 2.4 |

| Philippines (2013) | 3667 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 10.0 | 84.3 | 60.4 | 28.5 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 3.6 |

| Timor-Leste (2009–10) | 4835 | 12.7 | 3.5 | 28.5 | 54.7 | 43.8 | 32.0 | 10.1 | 0.9 | 4.0 |

| East Asia pooled | 22308 | 5.5 | 2.3 | 14.2 | 78.0 | 65.8 | 21.3 | 5.9 | 0.8 | 3.1 |

| Europe & Central Asia | ||||||||||

| Albania (2008–09) | 792 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 24.9 | 69.0 | 79.9 | 14.4 | 2.2 | 1.5 | 3.0 |

| Armenia (2010) | 826 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 3.4 | 93.8 | 81.3 | 17.1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 3.3 |

| Azerbaijan (2006) | 1195 | 19.4 | 7.5 | 20.7 | 49.2 | 56.6 | 13.4 | 6.8 | 2.8 | 3.4 |

| Kyrgyz Republic (2012) | 2195 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 9.9 | 83.9 | 79.1 | 15.2 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 3.1 |

| Moldova (2005) | 909 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 4.5 | 89.3 | 69.3 | 21.2 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 3.3 |

| Ukraine (2007) | 524 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 78.8 | 83.7 | 11.8 | 2.0 | 0.4 | 2.9 |

| Europe pooled | 6443 | 5.3 | 2.3 | 11.8 | 80.7 | 75.0 | 15.5 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 3.2 |

| Latin America & Caribbean | ||||||||||

| Bolivia (2008) | 4651 | 9.6 | 3.4 | 15.2 | 71.5 | 60.4 | 19.2 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 3.3 |

| Colombia (2010) | 8639 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 7.0 | 87.7 | 74.9 | 16.2 | 4.7 | 0.7 | 2.7 |

| Dominican Republic (2013) | 1945 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 2.4 | 95.4 | 81.1 | 14.6 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 2.6 |

| Guyana (2009) | 918 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 5.5 | 77.4 | 47.3 | 32.3 | 13.2 | 2.1 | 4.0 |

| Haiti (2012) | 3848 | 9.8 | 4.1 | 20.2 | 65.3 | 57.2 | 22.3 | 9.4 | 1.2 | 3.6 |

| Honduras (2011–12) | 5825 | 3.3 | 1.7 | 6.1 | 88.9 | 76.3 | 15.3 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 2.8 |

| Peru (2012) | 4923 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 3.5 | 94.2 | 73.6 | 17.6 | 6.3 | 0.9 | 2.9 |

| Latin America pooled | 30750 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 9.0 | 84.6 | 67.3 | 19.6 | 7.2 | 1.1 | 3.1 |

| Middle East | ||||||||||

| Egypt (2014) | 12579 | 8.7 | 0.6 | 6.6 | 82.8 | 76.3 | 11.1 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 2.6 |

| Jordan (2012) | 4841 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 4.0 | 94.5 | 90.7 | 6.3 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 2.3 |

| Middle East pooled | 17420 | 6.9 | 0.7 | 6.2 | 86.2 | 83.5 | 8.7 | 2.3 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| South Asia | ||||||||||

| Bangladesh (2014) | 4621 | 21.4 | 17.9 | 29.4 | 31.2 | 24.3 | 19.3 | 13.3 | 5.8 | 5.1 |

| India (2005–06) | 28655 | 23.0 | 6.0 | 33.5 | 37.0 | 43.0 | 22.7 | 8.3 | 2.3 | 3.8 |

| Maldives (2009) | 1977 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.7 | 85.6 | 91.4 | 6.3 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 1.8 |

| Nepal (2011) | 2847 | 14.4 | 6.2 | 27.8 | 51.6 | 50.3 | 26.5 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 3.7 |

| Pakistan (2012–13) | 5765 | 22.6 | 13.3 | 26.8 | 37.1 | 42.6 | 15.4 | 13.1 | 6.2 | 3.7 |

| South Asia pooled | 43866 | 21.3 | 8.2 | 31.0 | 39.4 | 50.3 | 18.0 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 3.6 |

| All countries | ||||||||||

| Pooled | 301546 | 8.6 | 3.3 | 22.9 | 62.4 | 58.0 | 17.4 | 8.0 | 2.9 | 3.4 |

aNumber of respondents in each country and region.

Variables

The outcome variable for this study was neonatal death, defined as death of a live-born during the first 28 complete days of life. The information on month and year of each birth, child’s survival status and current age or age at death, as applicable, was available in the data. Age at death was recorded in days if the child died within 1 month of birth.

The primary independent variables were the number of ANC visits and timing of first ANC visit. In this study, ANC refers to health care service provided to mother and fetus during pregnancy to ensure best outcome for both. The responses to the number of ANC visits were categorized into four: no visits, one visit, two to three visits and four or more visits. The timing of first ANC visit was categorized as: no visit, <4 months, 4–5 months, 6–7 months and 8+ months. WHO recommended at least four visits, with the first ANC visit as soon as possible in pregnancy, preferably in the first trimester for healthy women with no underlying medical problem.15 We therefore created a new variable based on the number and timing of first ANC visits: ‘those who did not meet the WHO recommendation’, ‘those who had the first ANC visit within the first trimester’, ‘those who had at least four ANC visits’ and ‘those who met both recommendations’.

The data on background characteristics of the mother [age, place of residence, body mass index (BMI), wealth quintile, children ever born, sex of child and education] were also available and included in the analysis as covariates in order to investigate the independent association between ANC attendance and neonatal mortality. The wealth quintile is the composite measure of the household’s cumulative living standard based on ownership of specified assets split into quintiles: poorest, poorer, middle, richer and richest.17

Statistical analysis

We applied sample weight to estimate the distribution of independent and dependent variables, to account for the cluster sampling structure. The weighted distribution of the independent variables and covariates was also presented, with the number of neonatal deaths in each category in the total sample. The DHS conducted editing and imputation of missing procedures before the data were released. We used Cox proportional hazard regression to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for neonatal mortality.

We created survival time in days: the time elapsed since birth in the case of children who were still alive, and between birth and death in the case of children who had died. To calculate the survival time in days, we imputed 15th day of the month for those whose days of birth were missing.

Adjusted hazard ratios for neonatal death were first calculated for the total sample, adjusting for each of the main independent variables (number of ANC visits, timing of first ANC visit and recommended ANC visits), the sociodemographic variables (maternal age, place of residence, BMI, wealth quintile, children ever born, sex of child and maternal education), year of survey and country. We also estimated the country- and regional-level hazard ratios with their 95% CIs to investigate the association of neonatal death with ANC attendance, adjusted for all studied soci-demographic variables. These estimates were plotted using the meta-analysis (metan) command in Stata.

Indonesia, the Philippines, Ukraine and Armenia were excluded from the country-level analysis due to few or no cases of neonatal mortality per the categories of the independent variable (recommended ANC visits) used. To examine the timing of death, we calculated the daily hazard rates for neonatal death during the first 28 completed days of life, stratified by WHO recommended ANC compliance. Survival curves for the infant during the first month of life, stratified by the regions to investigate the regional differences in neonatal survival rates, were also plotted. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA/SE 14.0.

Results

The distribution of main independent variables, ANC attendance (number of ANC visits and timing of first ANC visits) for each studied country and pooled values for the regions are presented in Table 1. Adjusted hazard ratios of the associations between neonatal mortality, ANC attendance and other maternal and demographic variables are shown in Table 2. The multivariable model shows that those who had two to three ANC visits (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.64–0.77) and four or more visits (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.50–0.59) had lower risk of neonatal death than those who had no care. The risk of neonatal death among those who had first ANC visits before 4 months was 41% lower (HR 0.59, 95% CI 0.54–0.65) than those who had no visit. When we combined the two recommendations into one variable, we found that the risk of neonatal death was 26% lower (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.67–0.83) among women who had first ANC visit within the first trimester of gestation, 51% lower (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.46–0.53) among those who had at least four ANC visits and 55% lower (HR 0.45, 95% CI 0.42–0.48) among those who met both recommendations compared with those who did not meet any of the recommendations.

Table 2.

Association of neonatal death with antenatal care (ANC) visits and other demographic characteristics at the most recent birth

| N a | Weighted percentage | Number of neonatal deaths | Adjusted HRb (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ANC visits | |||||

| No visits | 40939 | 13.4 | 1262 (3.1) | 1.0 | |

| 1 visit | 11029 | 3.6 | 318 (2.9) | 0.97 (0.83–1.12) | 0.700 |

| 2–3 visits | 79927 | 26.2 | 1745 (2.2) | 0.70 (0.64–0.77) | <0.001 |

| 4+ visits | 172892 | 56.7 | 2764 (1.6) | 0.54 (0.50–0.59) | <0.001 |

| Timing of first ANC visits (months) | |||||

| No visits | 36637 | 12.3 | 1176 (3.2) | 1.0 | |

| < 4 months | 125865 | 42.4 | 2165 (1.7) | 0.59 (0.54–0.65) | <0.001 |

| 4–5 months | 87275 | 29.4 | 1714 (2.0) | 0.62 (0.56–0.68) | <0.001 |

| 6–7 months | 41662 | 14.0 | 721 (1.7) | 0.58 (0.52–0.65) | <0.001 |

| 8+ months | 5399 | 1.8 | 118 (2.2) | 0.55 (0.42–0.71) | <0.001 |

| WHO recommendations for ANC visits | |||||

| Had not met any recommendations | 110257 | 36.3 | 2694 (2.4) | 1.0 | |

| Had first ANC visit within first trimester | 20918 | 6.9 | 573 (2.7) | 0.74 (0.67–0.83) | <0.001 |

| Had at least 4 ANC visits | 67945 | 22.3 | 1172 (1.7) | 0.49 (0.46–0.53) | <0.001 |

| Has met both recommendations | 104946 | 34.5 | 1592 (1.5) | 0.45 (0.42–0.48) | <0.001 |

| Maternal age group | |||||

| 15–19 | 32226 | 7.0 | 1233 (3.8) | 1.0 | |

| 20–24 | 120172 | 26.1 | 3770 (3.1) | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) | <0.001 |

| 25–29 | 134372 | 29.2 | 3480 (2.6) | 0.46 (0.42–0.50) | <0.001 |

| 30–34 | 91130 | 19.8 | 2403 (2.6) | 0.39 (0.35–0.43) | <0.001 |

| 35–39 | 55857 | 12.1 | 1675 (3.0) | 0.40 (0.35–0.45) | <0.001 |

| 40+ | 26877 | 5.8 | 956 (3.6) | 0.45 (0.40–0.52) | <0.001 |

| Area of residence | |||||

| Urban | 143975 | 31.3 | 3705 (2.6) | 1.0 | |

| Rural | 316659 | 68.7 | 9812 (3.1) | 1.02 (0.96–1.07) | 0.463 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| <18.5 | 42835 | 13.5 | 1521 (3.6) | 1.11 (1.04–1.18) | <0.001 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 198767 | 62.6 | 5780 (2.9) | 1.0 | |

| 25.0–28.9 | 53460 | 16.8 | 1496 (2.8) | 1.10 (1.04–1.17) | 0.001 |

| ≥30.0 | 22543 | 7.1 | 605 (2.7) | 1.20 (1.09–1.31) | <0.001 |

| Wealth quintile | |||||

| Poorest | 109491 | 23.8 | 3435 (3.1) | 1.0 | |

| Poorer | 101460 | 22.0 | 3108 (3.1) | 1.07 (1.01–1.14) | 0.017 |

| Middle | 94152 | 20.4 | 2751 (2.9) | 1.15 (1.08–1.23) | <0.001 |

| Richer | 85573 | 18.6 | 2442 (2.9) | 1.17 (1.09–1.25) | <0.001 |

| Richest | 69960 | 15.2 | 1780 (2.5) | 1.25 (1.15–1.36) | <0.001 |

| Children ever born | |||||

| 1 child | 76051 | 16.5 | 1690 (2.2) | 1.0 | |

| 2–3 | 190792 | 41.4 | 5372 (2.8) | 1.30 (1.20–1.40) | <0.001 |

| 4–5 | 103245 | 22.4 | 2977 (2.9) | 1.58 (1.44–1.74) | <0.001 |

| ≥6 | 90546 | 19.7 | 3476 (3.8) | 2.21 (1.99–2.46) | <0.001 |

| Sex of child | |||||

| Male | 234331 | 50.9 | 7778 (3.3) | 1.0 | |

| Female | 226304 | 49.1 | 5739 (2.5) | 0.75 (0.72–0.78) | <0.001 |

| Maternal education | |||||

| No education | 165692 | 36.0 | 5683 (3.4) | 1.0 | |

| Primary | 142532 | 30.9 | 4165 (2.9) | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | <0.001 |

| Secondary or more | 152412 | 33.1 | 3668 (2.4) | 0.94 (0.89–1.00) | 0.058 |

aFrequency distribution of each of the independent variables in the total sample. The total for each of the variables may not be same because of the missing information in ANC visits variables.

bAdjusted for all other factors in table and for the country and year of survey variables.

The risk of neonatal mortality among those who had at least one of the two WHO recommended ANC visit compared with those who did not meet any of the two recommendations, stratified by country and regions and sorted from lowest to highest risk, are presented in Figure 1. Country-level analysis shows that, in most countries, ANC attendance is associated with lower risk of neonatal mortality among those who met at least one WHO recommendation compared with those who did not. Similarly, per regions, a lower risk of neonatal mortality was found in all the regions among those who met at least one ANC recommendation compared with those who did not. The exception was in the Middle East & North Africa region (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.65–1.45) where no difference was found between these groups. The meta-analysis of the country-level risk shows 32% lower risk of neonatal death among those who met at least one recommendation (HR 0.68, 95% CI 0.61–0.75) than those who did not.

Figure 1.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and their 95% CI for the risk of neonatal mortality among those who met at least one ANC recommendation. The model was adjusted for maternal age, area of residence, BMI, wealth quintile, children ever born, sex of child and maternal education.

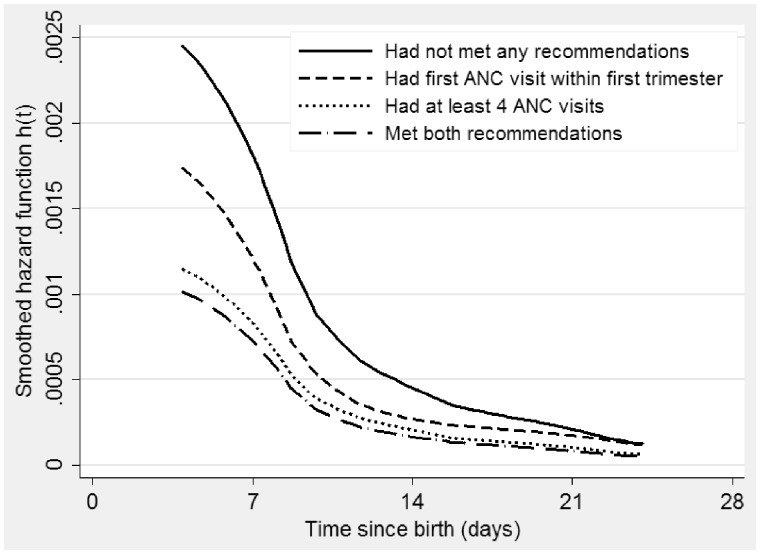

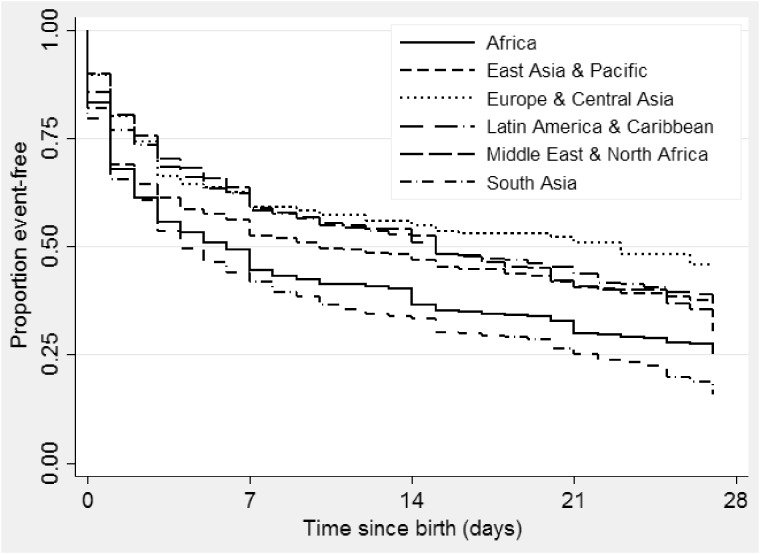

The hazard was highest in the first week of life. It decreased sharply after the first week (Figure 2). Infants born to mothers who did not meet the WHO recommendations had greater excess hazard of dying during the first month of life than those born to mothers who fulfilled both or at least one recommendation. The risk was lowest among those who met both recommendations. The Europe and Central Asia region experienced better survival, whereas the South Asia region had the worst survival (Figure 3). The regional differences in the neonatal survival were statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Daily hazard of neonatal mortality for infants during the first month of life, stratified by recommended ANC visit of mother.

Figure 3.

Daily survival curves from neonatal mortality for infant during the first month of life stratified by the region.

Discussion

Using a unique and comparable data set (N = 464 728) collected from 2005 to 2015, we conducted survival analysis on the influence of ANC attendance on neonatal death in 57 LMICs. ANC attendance is protective against neonatal mortality in most of the countries studied. After adjusting for potential confounding factors in pooled analysis, we found 55% lower risk of neonatal mortality among women who met both WHO recommendations for ANC. Furthermore, ANC attendance was found to be protective against neonatal mortality in all the regions except in the Middle East and North African region where no difference was found. Additionally, meta-analysis shows a 32% reduced risk of neonatal mortality among women who met at least one WHO recommendation in the LMICs studied. As expected, we found a greater hazard during the early neonatal period, similar to that found by an earlier study which explored other risk factors of neonatal mortality in some LMICs.18 Nonetheless, children born to mothers who did not meet any of the WHO recommendations, or met just one of them, had excess risk throughout the neonatal period compared with those who met both recommendations.

ANC visits are potentially beneficial for both the baby and the mother. ANC is an opportunity for promoting healthy behaviour among mothers as well as promotion of parenting skills, which are particularly important for new mothers.

In 2016, the WHO introduced new guidelines for ANC, which recommend a minimum of eight ANC contacts during pregnancy and the first contact is recommended to be within the first 12 weeks of gestation.19 The goal of this new guideline is to fully use the opportunity of providing ANC to save lives. Our findings suggest that this new recommendation is important, timely and can contribute to ending some preventable neonatal deaths in LMICs. Furthermore, in LMICs where HIV infection is high, the ANC visit offers mothers the opportunity to be screened for the virus, and those who test positive can be treated to prevent mother to child transmission. This might also contribute to neonatal survival. Women who attend ANC might be advised to seek out skilled delivery care or institutional delivery, as well as postnatal care (PNC). It has been shown that women who attend ANC are more likely to have institutional care during labour.20 An association between ANC attendance and skilled delivery care has also been reported,21 although with some exceptions.22 Both institutional delivery and skilled delivery care can contribute to improving neonatal outcome. This could explain our finding of an association between ANC attendance and neonatal survival. In addition, our finding of higher child mortality in the first few days of life emphasizes the importance of PNC alongside ANC. In this respect, the quality of ANC is essential. It is unknown whether women who met the recommended ANC visits also received these recommended services or whether the service providers have the adequate knowledge, skills, supplies and equipment to deliver high quality care.

This study underscores the crucial importance of ANC to child survival in LMICs. Apart from the role of ANC attendance in predicting neonatal mortality, we also explored the role of other sociodemographic factors, including maternal education and BMI, in the risk of neonatal death in LMICs. These findings are similar to those reported in earlier studies.18,23 A number of studies have also reported some of these sociodemographic factors as predictors of ANC.13,16

Our findings, of independent association between ANC attendance and neonatal mortality in relation to these earlier studies, emphasize the complexity of the risk for neonatal death, which should inform interventions in LMICs. Earlier studies have identified a number of barriers to ANC utilizations, including cost and provider barriers, in developing countries.24,25 Although barriers might be country-specific, the evidence of substantial reduction in neonatal mortality risk by ANC attendance, found in the present study, means that conscious efforts at addressing these barriers at local, national and regional levels are necessary to improve neonatal health in LMICs. We found regional differences: ANC attendance was found to be protective against neonatal mortality in all the regions except in the Middle East and North African region. Given that data from only two countries in this region were available and included in this study, the interpretation of the regional differences should be done with caution.

In the DHS, antenatal health care utilization was self-reported and may be biased by social desirability within the society where the women lived. Also, ANC attendance was measured for births within the past years preceding the study; hence it may be affected by recall bias. What constitutes ANC in each country may vary–ANC might not necessarily mean care by skilled health personnel, and thus the result should be interpreted within this context. Causal inference is limited due to the cross-sectional nature of the data.

Furthermore, data on births and deaths from which the neonatal mortality was estimated were reported retrospectively by mothers and could be subject to recall bias. However previous studies, which validated such measures in retrospective and longitudinal surveys, found them to be accurate.26 Initial assessment of the health data in the DHS-I suggests that they are accurate estimates.27 We did not investigate the quality of antenatal care in this study, as the focus was mainly on the association between ANC attendance and neonatal mortality. Future studies, which will explore the quality of ANC delivery in LMICs and how it relates to neonatal mortality as well as the aspects of ANC that are beneficial to neonatal survival, will contribute further to the present findings. Such studies should also explore the link between ANC and PNC and their effects on neonatal survival in these countries.

Conclusions

We conclude that ANC is protective against neonatal mortality in the LMICs studied, although differences exist across the countries and by region. Our study provides a comprehensive overview on the association between ANC visits and neonatal mortality in nearly half of the world’s LMICs. This study contributes to the literature on the subject and clarifies the importance of ANC visits on a health outcome of global importance. To address the huge burden of neonatal mortality in these countries, it is important to increase ANC coverage and attendance.

The data are publicly available at [http://dhsprogram.com/Data/]. Permission to use the data is required from Measure DHS.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mr Jani Raitanen of the School of Health Sciences, University of Tampere, Finland, and Mr George Adjei of the Kintampo Health Research Centre, Ghana, for their involvement in the validation of the data.

Authors contributions

S.N. and D.T.D. conceptualized the study and developed the analytical strategy. D.T.D. and S.N. conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. Both authors did the critical revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Key Messages

This paper is the first to investigate, using comparable data, the association between antenatal care visits and neonatal mortality in low- and middle-income countries.

In pooled analysis, 55% reduced risk of neonatal mortality was found among women who met both WHO recommendations (first visit within the first trimester and at least four visits during pregnancy).

Meta-analysis of country-level risk shows that meeting at least one antenatal care recommendation reduced the risk of neonatal mortality by 32%.

Increased ANC visits, along with other known effective interventions, will improve neonatal survival in low- and middle-income countries.

References

- 1. United Nations. Official List of MDG Indicators. 2008. http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Host.aspx?Content=indicators/officiallist.htm (29 July 2016, date last accessed).

- 2. United Nations. Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20%28July%201%29.pdf (28 July 2016, date last accessed).

- 3. World Health Organization. Every Newborn: An Action Plan to End Preventable Deaths. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/127938/1/9789241507448_eng.pdf?ua=1 (28 July 2016 date last accessed).

- 4. Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Oza S. et al. Every newborn: progress, priorities, and potential beyond survival. Lancet 2014;18:189–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Houweling TA, Kunst AE, Looman CW, Mackenbach JP. Determinants of under-5 mortality among the poor and the rich: a cross-national analysis of 43 developing countries. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:1257–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Houweling TA, Kunst AE. Socio-economic inequalities in childhood mortality in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the international evidence. Br Med Bull 2010;93:7–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J, ; Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team . Four million neonatal deaths: when? where? why? Lancet 2005;365:891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lawn JE, Kerber K, Enweronu-Laryea C, Cousens S. 3.6 million neonatal deaths—what is progressing and what is not? Semin Perinatol 2010;34:371–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (2 November 2016, date last accessed).

- 10. Raatikainen K, Heiskanen N, Heinonen S. Under-attending free antenatal care is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. BMC Public Health 2007;7:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hollowell J, Oakley L, Kurinczuk JJ, Brocklehurst P, Gray R. The effectiveness of antenatal care programs to reduce infant mortality and preterm birth in socially disadvantaged and vulnerable women in high-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2011;11:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ibrahim J, Yorifuji T, Tsuda T, Kashima S, Doi H. Frequency of antenatal care visits and neonatal mortality in Indonesia. J Trop Pediatr 2012;58:184–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh A, Pallikadavath S, Ram F, Alagarajan M. Do antenatal care interventions improve neonatal survival in India? Health Policy Plan 2014;29:842–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L. et al. Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;10:CD000934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization. WHO Recommended Interventions for Improving Maternal and Newborn Health. 2nd edn. Geneva: WHO Department of Making Pregnancy Safer, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Neupane S, Doku DT. Determinants of time of start of prenatal care and number of prenatal care visits during pregnancy among Nepalese women. J Community Health 2012;37:865–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Demographic and Health Survey Measure. Standard Recode Manual for DHS 6. Calverton, MD: MEASURE DHS, USAID, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cresswell JA, Campbell OM, De Silva MJ, Filippi V. Effect of maternal obesity on neonatal death in sub-Saharan Africa: multivariable analysis of 27 national datasets. Lancet 2012;380:1325–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva: WHO, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mengistu TA, Tafere TE. Effect of antenatal care on institutional delivery in developing countries: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 2011;9:1447–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guliani H, Sepehri A, Serieux J. What impact does contact with the prenatal care system have on women’s use of facility delivery? Evidence from low-income countries. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1882–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stanton C, Blanc AK, Croft T. et al. Skilled care at birth in the developing world: progress to date and strategies for expanding coverage. J Biosoc Sci 2007;39:109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fink G, Ross R, Hill K. Institutional deliveries weakly associated with improved neonatal survival in developing countries: evidence from 192 Demographic and Health Surveys . Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1879–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Finlayson K, Downe S. Why do women not use antenatal services in low- and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Med 2013;22:e1001373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matsuoka S, Aiga H, Rasmey LC, Rathavy T, Okitsu A. Perceived barriers to utilization of maternal health services in rural Cambodia. Health Policy 2010;95:255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garenne M, van Ginneken J. Comparison of retrospective surveys with a longitudinal follow-up in Senegal: SFS, DHS and Niakhar. Eur J Popul 1994;10:203–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Macro International Inc. 1993. An Assessment of the Quality of Health Data in DHS-I Surveys. DHS Methodological reports No.2. Calverton, MD: Macro International Inc., 1993. [Google Scholar]