Abstract

The Saguenay Youth Study (SYS) is a two-generational study of adolescents and their parents (n = 1029 adolescents and 962 parents) aimed at investigating the aetiology, early stages and trans-generational trajectories of common cardiometabolic and brain diseases. The ultimate goal of this study is to identify effective means for increasing healthy life expectancy. The cohort was recruited from the genetic founder population of the Saguenay Lac St Jean region of Quebec, Canada. The participants underwent extensive (15-h) phenotyping, including an hour-long recording of beat-by-beat blood pressure, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain and abdomen, and serum lipidomic profiling with LC-ESI-MS. All participants have been genome-wide genotyped (with ∼ 8 M imputed single nucleotide polymorphisms) and a subset of them (144 adolescents and their 288 parents) has been genome-wide epityped (whole blood DNA, Infinium HumanMethylation450K BeadChip). These assessments are complemented by a detailed evaluation of each participant in a number of domains, including cognition, mental health and substance use, diet, physical activity and sleep, and family environment. The data collection took place during 2003–12 in adolescents (full) and their parents (partial), and during 2012–15 in parents (full). All data are available upon request.

Why was the cohort set up?

The Saguenay Youth Study (SYS; [http://www.saguenay-youth-study.org]) is a population-based study of adolescents and their middle-aged parents. It is aimed at investigating the aetiology, early stages and trans-generational trajectories of common cardiometabolic and brain diseases. The ultimate goal is to identify effective means for increasing healthy life expectancy.1

The design of the SYS was motivated by the following biomedical considerations: (i) many common cardiometabolic and brain diseases originate in utero; (ii) they involve interactions between adverse environments and vulnerability genes; (iii) many of these diseases emerge during adolescence and become established during middle-aged adulthood; and (iv) most of them are multi-systemic, affecting both the brain and the rest of the body.

Our main methodological considerations were: (i) genetics can be used to uncover aetiology and mechanistic pathways; (ii) emergence and trans-generational trajectories of disease phenotypes can be monitored through high- fidelity ‘intermediary’ (pre-clinical) phenotypes; (iii) multi- system (cardiovascular, metabolic and cognitive) and multi-level (environment, tissues and molecules) assessments of each participant are necessary to understand how these systems and levels interact as part of an integrated whole—the human body; (iv) studies of complex genetic traits, such as common cardiometabolic and brain diseases, benefit from reduced genetic and environmental heterogeneity; and (v) disease risk and early disease processes can be tagged by easily assessable and highly predictive genetic, epigenetic and molecular biomarkers.

Finally, the SYS was designed as a retrospective study of long-term outcomes of prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking. The choice of this particular prenatal adversity reflected high prevalence of maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy2,3and the reports of long-term cardiometabolic4–6and behavioural7–10abnormalities in the exposed offspring. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy was common; in Canada and the USA, for example, close to 40% of pregnant women smoked in the 60s and 70s. Over 40 years later, the proportion of pregnant women smoking during pregnancy is still high (12–16%). Importantly, this number has not been declining in recent years;2,3 it is even higher (> 20%) in vulnerable groups, such as pregnant teenage girls and women with low education attainment.3,7 Thus, a large proportion of the population has been and continues to be exposed prenatally to maternal cigarette smoking.

Who is in the cohort?

The SYS cohort includes 1029 adolescents and their 962 parents. The cohort was recruited via adolescents attending high schools in the Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec, Canada. The region is home to the largest genetic founder population in North America.11–14 Both maternal and paternal grandparents of the adolescents were required to be of French-Canadian ancestry and born in the region; as such, all adolescents and their parents are of a single ethnicity [European (French) ancestry]. Half of the adolescents were exposed prenatally to maternal cigarette smoking. The cohort is family based (481 families), including only adolescents who have one or more siblings of similar age (12 to 18 years) and both biological parents of the French-Canadian origin born in the region. The data collection occurred in two waves. Wave 1 involved the recruitment and ‘complete assessment’ of all 1029 adolescents, as well as a ‘partial assessment’ of 962 parents. Wave 2 involved the ‘complete assessment’ of an available (and willing) subset of the parents (n = 664). Characteristics of the SYS cohort are provided in Tables 1 and 2, and in Tables S1–S4 (available as Supplementary data at IJE online).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of participants

| Adolescents |

Parents |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

| Measure | Count, mean ± SD or proportion | Count, mean ± SD or proportion | |

| Number of participants | 1029 | 962 | 664 |

| Number of families | 481 | 481 | 382 |

| Age (years) | 15.0 ± 1.8 | 43.3 ± 4.6 | 49.2 ± 5.0 |

| Sex (%, males/females) | 48/52 | 50/50 | 45/55 |

| Household CAD income (%) | |||

| ≤ $20,000 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| $30,000-$40,000 | 19 | 19 | 20 |

| $50,000-$60,000 | 24 | 24 | 24 |

| $70,000-$80,000 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| ≥ $85,000 | 24 | 24 | 23 |

| Education (%) | |||

| No high school | 0 | 1 | < 1 |

| Some high school | 1029 | 16 | 15 |

| High school | 0 | 51 | 53 |

| College degree | 0 | 19 | 19 |

| Bachelor’s | 0 | 9 | 8 |

| Master’s or doctorate | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| Unknown | 0 | < 1 | < 1 |

Table 2.

Wave 1 ‘complete’ assessment of adolescents (n = 1029): phenotyping domains and tools

| Domain | Tool | Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|

| Brain | MRI | Global and regional volumes; cortical surface and thickness; MTR |

| Cognition | 6-hour battery | PIQ and VIQ; memory; executive functioning, phonological and motor skills; social cognition |

| Mental health | DPS, GRIP | Epidemiological diagnoses; symptom counts |

| Substance use | GRIP | Cigarette smoking, cannabis, alcohol use, drug experimentation (age of initiation, past 30 days, binge drinking) |

| Personality | NEO-PI-R | Neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness |

| Cardiovascular | Finometer | Beat-by-beat blood pressure, heart rate, stroke volume, total peripheral resistance at rest and in response to physical and mental challenges (52-min protocol) |

| Autonomic balance | Power spectral analysis | Low- and high-frequency powers of inter-beat interval and low-frequency power of blood pressure; sympathetic and parasympathetic tone |

| Body composition | Anthropometry, MRI, bioimpedance | Height, weight, circumferences, skinfolds; subcutaneous and visceral fat and muscle volumes; fat and muscle mass |

| Glucose/lipid metabolism | Blood | Glucose, insulin, cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, leptin, C-reactive protein |

| Lipidomicsa | Blood (LC-ESI-MS) | ∼ 700 lipid species |

| Hormones | Blood | Testosterone, estrogen, cortisol |

| Hormones | Saliva | Cortisol (before and after mental stress) |

| Genetic variation | Blood DNA | Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChip and HumanOmniExpress BeadChip; a total of 7 746 837 typed and imputed SNPs |

| Epigenetic variationb | Blood DNA | Infinium HumanMethylation450K BeadChip (> 485 000 CpGs) |

| Sexual maturation | PDS | Stages of pubertal development (Tanner stages) |

| Lifestyle | Lerner | Sleep, physical activity, extracurricular activities, sexuality, academic/vocational aspirations |

| Diet | 24-hour food recall | Energy and nutrient intake |

| Family environment | FamEnvi | Stressful life events, financial difficulties, SES (family income, parental education) |

MTR, magnetization transfer ratio; DPS, DISC Predictive Scales; GRIP, Groupe de Recherche sur l’Inadaptation Psychosociale, adolescent self-assessment of mental health and substance use developed for the SYS by J. R. Séguin based on validated National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY) and Quebec Longitudinal Study of Child Development (QLSCD)31 protocols; Lerner, adolescent self-assessment developed by Richard Lerner; PIQ, performance intelligence quotient; VIQ, verbal intelligence quotient; SES, socioeconomic status; PDS, Puberty Development Scale; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein; LC-ESI-MS, liquid-chromatography electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry; Family Environment, questionnaire on family environment developed by the SYS team; NEO-PI, Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness Personality Inventory.15

In progress.

Assessed in a subset of 144 adolescents.

Recruitment

Wave 1 took place over a 10-year period (2003–12). Recruitment was conducted via high schools. During the 10-year period, our team made 28 visits to schools, contacting a total of 27 190 students (18 127 families). Of the 18 127 families, 5570 (33%) sent a response card; of these, 3269 families (59%) indicated their interest in the study and 2301 families (41%) declined further participation. Based on the inclusion (e.g. maternal smoking during pregnancy, two or more siblings per family) and exclusion [e.g. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contraindications] criteria,15a total of 1801 families (55% of the interested families) were eligible to participate in the study; a research nurse determined the eligibility via a structured telephone interview with the mother. From these, 481 families participated in the study. ‘Exposed’ adolescents were recruited first; we defined exposure as maternal cigarette smoking of at least 1 cigarette/day during the second trimester of gestation. The ‘non-exposed’ adolescents were matched to the ‘exposed’ adolescents by the level of maternal education and by the high school attended. Maternal cigarette smoking before and during pregnancy was ascertained retrospectively by a research nurse who conducted a structured telephone interview with the mother. We found ‘good’ agreement between the exposure status noted in the medical records at the time of pregnancy and the maternal report during the telephone interview (Kappa statistics = 0.69 ± 0.04; assessed in the first 260 SYS participants). Siblings were concordant for the exposure status in the majority of families (446/481 families; 93%).

Wave 2 took place during a 3-year period between 2012 and 2015. We contacted all 962 parents by mail and telephone. A total of 664 were interested in participating and underwent the complete assessment. The remaining 282 parents declined our invitation to participate and 16 parents were deceased. Parents who participated vs those who declined did not differ by age (P = 0.87), household income (P = 0.40) or education (P = 0.73), but they did differ by sex [the proportion of men was lower in the participating (46% men, 54% women) vs declining (57% men, 43% women) groups of parents, P = 0.001].

Further follow-up of both adolescents and parents (as young and ageing adults) is planned.

What has been measured?

The data collection took place in two waves. Wave 1 (2003–12) involved the recruitment and complete assessment of all 1029 adolescents (Table 1), as well as a partial assessment of all 962 parents (Table 2). Wave 2 (2012–15) involved the complete assessment of 664 parents (Table 1). Linkage to health registries is in progress.

Wave 1: complete assessment of adolescents

The ‘complete’ assessment of adolescents took place over several sessions (∼ 15 h in total) and included a number of domains (Table 2). Each adolescent provided a fasting (morning) blood sample. The key features of the phenotyping protocol were: (1) MRI of the brain and abdomen; (ii) 1-h cardiovascular assessment; and (iii) 6-h cognitive evaluation.

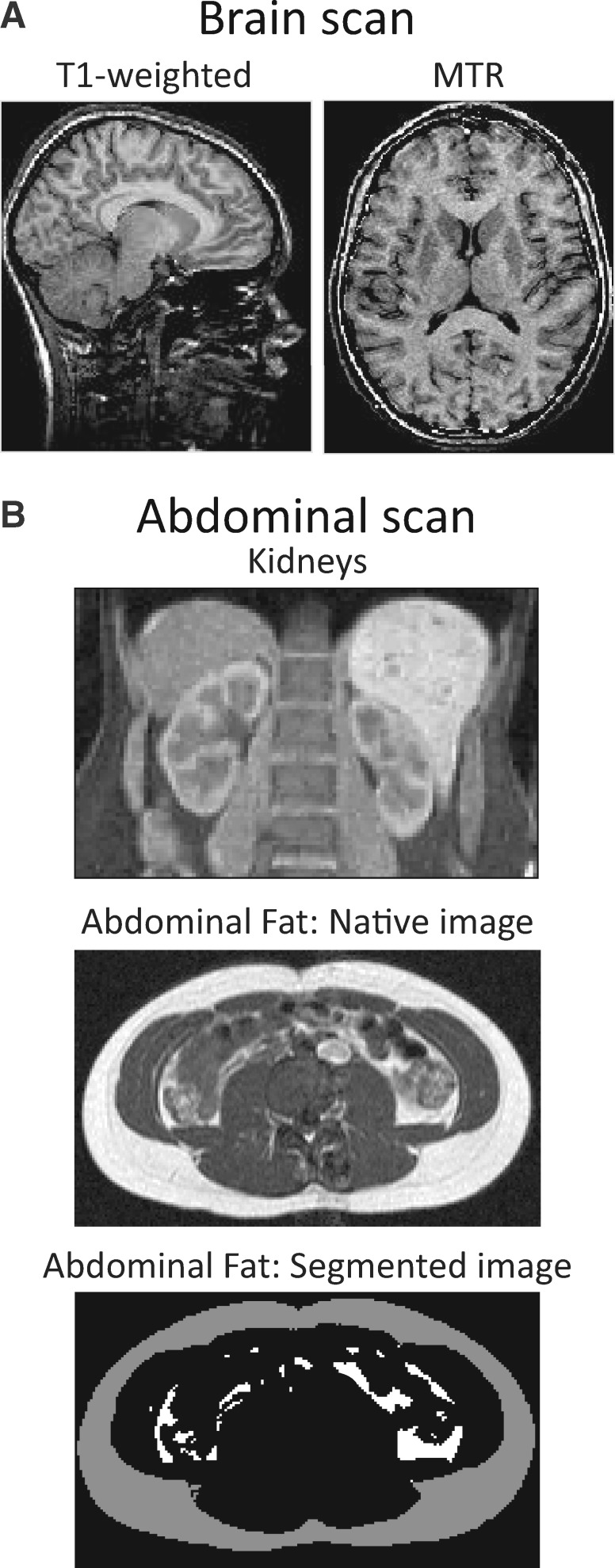

MRI of the brain and abdomen

(Figure 1): brain MRI was used to assess structural and volumetric features of the brain. Two types of magnetic resonance images were acquired: (i) T1-weighted images, which are used for deriving a number of anatomical features (e.g. global and regional volumes of grey and white matter, cortical thickness and surface area, and normalized MR intensities); and (ii) magnetization-transfer ratio (MTR), which provides insights into micro-structural properties of white matter, such as the relative content of myelin and axons. Abdominal MRI was used to quantify visceral and subcutaneous fat using a semi-automated method.16

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain (A) and abdomen (B). (A) T1-weighted images are used for deriving a number of anatomical features (e.g. global and regional volumes of grey and white matter, cortical thickness and surface area); and images of the magnetization-transfer ratio (MTR) provide insights into micro-structural properties of white matter, such as the relative content of myelin and axons (B); a set of heavily T1-weighted images are acquired during a single breath-hold and these are used to measure volumes of the kidneys (middle) and to segment the subcutaneous and visceral fat, respectively. A transverse slice (position at the level of the umbilicus) shows the native and segmented images (bottom); on the segmented image, subcutaneous and visceral fat are shown, respectively, in grey and white.

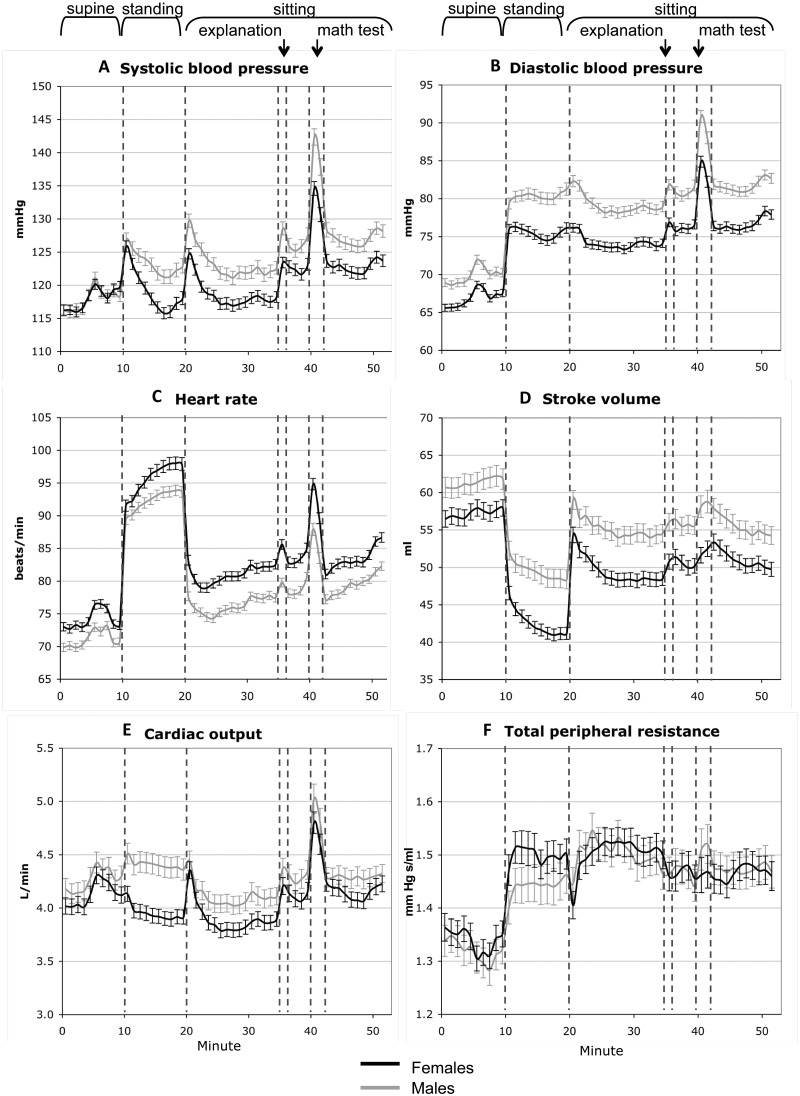

Cardiovascular assessment

(Figure 2) involved a 52-min protocol during which beat-by-beat blood pressure (BP) was monitored at rest and in response to simple physical and mental challenges mimicking daily-life activities, using Finometer (FNS Finapres, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The Finometer monitors continuously finger blood flow17 and, by the reconstruction and level-correction of the finger blood-flow waveform, it derives beat-by-beat brachial systolic and diastolic BPs, as well as a number of haemodynamic parameters including inter-beat interval, stroke volume, cardiac output, ventricular ejection time, peripheral resistance, aortic impedance and aortic compliance. The Finometer has been approved as a reliable device for tracking BP in adults and children older than 6 years18,19 and the precision of BP measurement by this device meets the American Association for the Advancement of Medical Instruments (AAAMI) requirements.20,21

Figure 2.

Blood pressure and underlying haemodynamic parameters. Unadjusted 1-min means and standard errors of the mean of systolic blood pressure (A). Diastolic blood pressure (B), heart rate (C), stroke volume (D), cardiac output (E) and total peripheral resistance (F) are shown for girls and boys during a 52-min cardiovascular protocol that includes postural and mental challenges. Reprinted with permission from Syme et al.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009;163:818-25.

The beat-by-beat recordings of diastolic BP and inter-beat interval were analysed with power spectral analysis (PSA)22to assess cardiovascular autonomic function, a key component of hypertension aetiology.23–25 Low-frequency power of diastolic BP is considered a proxy of sympathetic modulation of vasomotor tone,26–28 and high-frequency power of inter-beat interval is considered a proxy of parasympathetic modulation of cardiac chronotropic function.29

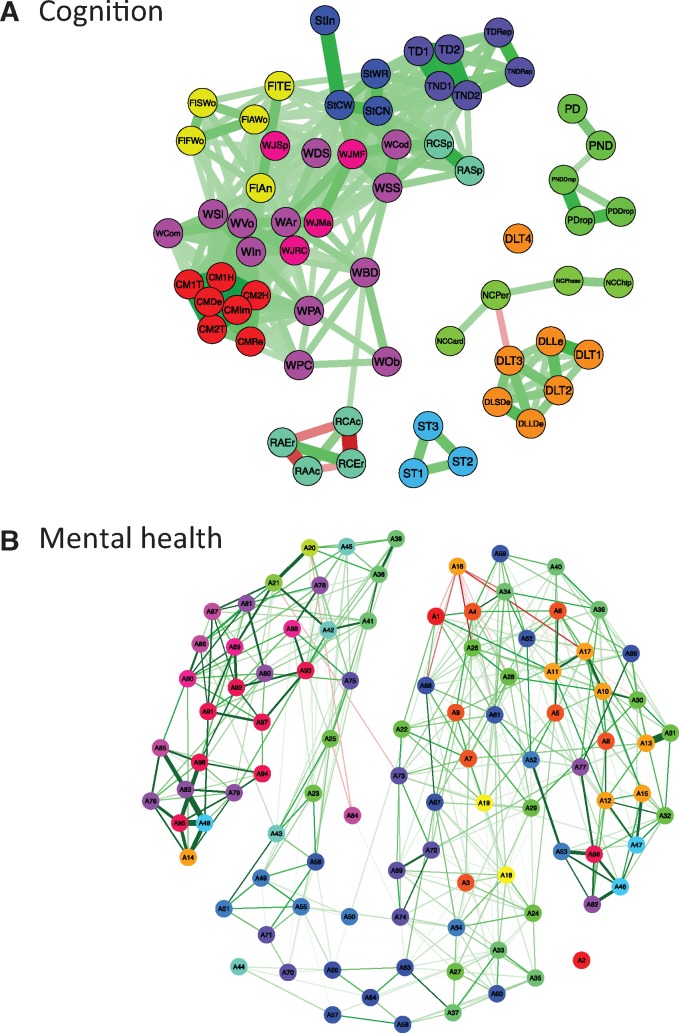

Cognitive assessment

(Figure 3A) was carried out by trained psychometricians in two 3-h sessions (separated by a lunch break) on the same day. This assessment consisted of two types of tests: (i) standardized psychological instruments; and (ii) domain-specific tests. The standardized tests included the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children WISC-III (except Mazes), Woodcock–Johnson Achievement subtests (reading comprehension and arithmetic and a spelling test) and Children’s Memory Scale (Dot Locations and Stories). Domain-specific tests included tests of executive functions (self-ordered pointing, word fluency, resistance to interference), phonological skills and frequency-modulation auditory threshold, delayed auditory feedback, phonological learning, fine motor skills and motor coordination, number sense, and emotion and motivation (morphed facial expressions, repeated failure test and a gambling task).

Figure 3.

Visualization of the cognition (A) and DPS-based symptom (B) matrices as networks. (A) The cognition variables (n = 63; age-adjusted) are represented as nodes and connected by an edge if the correlation exceeds r = 0.3. In the electronic version, green (red) edges indicate positive (negative) correlations. Line thickness corresponds to strength of correlation, i.e. thicker lines represent stronger correlations. In the electronic version, colour of nodes represents the cognitive instrument used to derive a particular measure. (B) Visualization of the DPS-based symptom matrices as networks. The symptom variables (n = 98; age-adjusted) are represented as nodes and connected by an edge if the correlation exceeds r = 0.1. In the electronic version, green (red) edges indicate a positive (negative) correlation. Line thickness corresponds to strength of correlation, i.e. thicker lines represent stronger correlations. In the electronic version, colour of nodes represents the different DPS-based diagnostic categories [DPS, Diagnostic Schedule for Children (DISC) Predictive Scales].

Mental health and substance use

(Figure 3B) were assessed using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) Predictive Scales (DPS);30 it contains questions about 98 symptoms (18 diagnostic categories, such as generalized anxiety disorder) the adolescent may have experienced in the past year. The DPS contains also questions about problems associated with use of alcohol (four questions), marijuana (three questions) and other substances (eight questions). In addition, we administered another questionnaire (Groupe de Recherche sur l’Inadaptation Psychosociale, GRIP) focusing on anti-social behaviour (e.g. stealing, fighting), hyperactivity and inattention, and anxiety and depression, as well as smoking, drinking (including binge drinking) and the use of other illicit substances,31 as well as a questionnaire focusing on the key components of positive youth development.32

Wave 1: partial assessment of parents

The ‘partial’ assessment protocol of parents took place over two sessions; telephone interview with the mother, and a home visit. A research nurse conducted both sessions. During the telephone interview, which was always conducted with the mother, information on her life habits during pregnancies and on the medical history of her children was acquired. During the home visit, mothers (99% of families) filled out a series of questionnaires about the family environment, and each parent answered questions about her/his mental health (anxiety and depression) and substance use; the latter included questions about cigarette smoking, alcohol use and drug experimentation throughout their life (including current habits); and the presence of antisocial behaviour (at present and during her/his adolescence; Table 3). Parents also provided a convenience blood sample for genetic analyses, and self-reported weight and height.

Table 3.

Wave 1 ‘partial’ assessment of parents (n = 962): phenotyping domains and tools

| Domain | Tool | Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|

| Family environment | FamEnvi | Stressful life events, financial difficulties, SES (family income, parental education) |

| Mental health | GRIP adult | Symptom counts (depression, anxiety, antisocial behaviour) |

| Substance use | GRIP adult | Cigarette smoking, alcohol use, drug experimentation |

| Medical history | Medical questionnaire | Personal and family history of cancer, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, lipid disease, psychiatric disorders |

| Genetic variation | Blood DNA | Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChip and HumanOmniExpress BeadChip; a total of 7 746 837 typed and imputed SNPs |

| Epigenetic variationa | Blood DNA | Infinium HumanMethylation450K BeadChip (> 485 000 CpGs) |

FamEnvi, questionnaire on family environment developed by the SYS team; GRIP Adult, self-assessment of mental health and substance use, as adapted by J. R. Séguin at the Groupe de Recherche sur l’Inadaptation Psychosociale of the University of Montreal.

Assessed in a subset of 288 parents

Wave 2: complete assessment of parents

The ‘complete’ assessment of parents (Table 4) was similar to the ‘complete’ assessment of adolescents (Table 2). The following additions and adjustments have been made to the brain MRI protocol, cognitive evaluation and assessment of mental health and substance use.

Table 4.

Wave 2 ‘complete’ assessment of parents (n = 664): phenotyping domains and tools

| Domain | Tool | Phenotypes |

|---|---|---|

| Brain | MRI | Global and regional volumes; cortical surface and thickness; white-matter hyperintensities; magnetization transfer ratio; diffusion tensor imaging (DTI); resting state functional MRI |

| Cognition | Cambridge Brain Sciences Platform | Executive functioning; attention; learning and memory; reasoning; spatial skills |

| Mental health | MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview; Mental Health and Addiction Questionnaire; ASR; CES-D; Family History Screen | Depression, anxiety, attention-deficit hyperactive disorder, antisocial personality disorder; post-traumatic stress disorder; obsessive compulsive disorder; alcohol and substance dependence, bulimia, anorexia; family history of psychiatric disorders |

| Substance use and addiction | Mental Health and Addiction Questionnaire; YFAS; FNDS; AUDIT; SRE; ESPAD; IAT; OGS | Cigarette smoking, alcohol and drug use, gambling, internet addition, food addiction |

| Personality | NEO-FFI | Neuroticism, extroversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness |

| Cardiovascular | Finometer | Beat-by-beat blood pressure, heart rate, stroke volume, total peripheral resistance at rest and in response to physical and mental challenges (52-min protocol) |

| Autonomic balance | Power spectral analysis | Low- and high-frequency powers of inter-beat interval and low-frequency power of blood pressure; sympathetic and parasympathetic tone |

| Body composition | Anthropometry, MRI, bioimpedance | Height, weight, circumferences, skinfolds; subcutaneous and visceral fat and muscle volumes; fat and muscle mass |

| Lung function | Spirometer | Forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume |

| Glucose lipid metabolism | Blood | Lipid profile (TG, TC, HDL-C, LDL-C), glucose, insulin, free fatty acids, glycerol, C-reactive protein |

| Lipidomicsa | Blood, LC-ESI-MS | 700 lipid species |

| Diet | 24-h food recall | Energy and nutrient intake |

| Medical history | Medical Questionnaire | Personal and family history of: cancer, hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, lipid disease, psychiatric disorders, addiction; reproductive and sexual health; medications |

| Lifestyle | Life Experiences Questionnaire; PBI; Hand Preference | Family characteristics; education; socioeconomic status; physical activity; sexual activity; parental style; hand laterality |

| Sleep | PSQI; ESS | Sleep quality, latency, duration, efficiency and disturbances; daytime sleepiness |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MINI, International Neuropsychiatric Interview34; Mental Health and Addiction Questionnaire adapted from the Ontario Health Study and the Wave-1 questionnaire developed by the SYS team; ASR, Adult Self Report35; CES-D, Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale36; YFAS, Yale Food Addiction Scale80; FNDS, Fagerström’s Nicotine Dependence Scale81; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test82; SRE, Subjective Response to Ethanol83; ESPAD, European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs84; IAT, Internet Addiction Test85; SOGS, South Oaks Gambling Screen86; NEO-FFI, NEO-Five Factor Inventory87; Life Experiences Questionnaire adapted from the OHS www.ontariohealthstudy.ca and the Wave-1 questionnaire developed by the SYS team; PBI, Parental Bonding Instrument88; Hand Preference adapted from89; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index90; ESS, Epsworth Sleepiness Scale91; Medical Questionnaire adapted from the Ontario Health Study [www.ontariohealthstudy.ca]; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; CRP, C-reactive protein; LC-ESI-MS, liquid-chromatography electrospray- ionization mass spectrometry.

In progress.

MRI protocol

(Table 4) In addition to T1-weighted images and MTR, the MRI protocol includes diffusion-weighted imaging (DTI) and resting-state functional MRI.

Cognitive performance

was assessed using the Cambridge Brain Sciences platform [www.cambridgebrainscience.com],33 a computer-based battery of 12 tests designed to assess executive functioning, reasoning, working memory and visual-spatial skills. Participants completed the cognitive battery under the supervision of study personnel. The 12 tasks include: colour-word remapping, spatial planning, self-ordered search, paired associates learning, digit span, spatial span, visuospatial working memory, interlocking polygons, feature match, odd one out, grammatical reasoning and spatial rotation (Table 4).

Mental health

was assessed with the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview.34 Adult Self Report35 and Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale36(CES-D). Cigarette smoking, alcohol and drug use, gambling, internet addiction and food addiction were assessed with a number of standard questionnaires (Table 4).

Blood sample-derived assessments

Genome-wide genotyping and epityping was carried out with DNA from peripheral blood cells using the adolescent and parent blood samples collected during Wave 1. Targeted lipidomics profiling was conducted with fasting sera collected from adolescents during Wave 1 and parents during Wave 2.

Genome-wide genotyping

was carried out with the Human610-Quad and HumanOmniExpress BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Following genotype imputation, a total of 7 746 837 typed and imputed SNPs are available for analysis.

Genome-wide epityping

was performed using the Infinium HumanMethylation450K BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA) in 144 adolescents and 288 parents.

Serum lipidomics

targeted lipidomics profiling is currently conducted using fasting serum samples in all adolescents and parents. Liquid chromatography, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS) are used to identify and quantify serum glycerophospholipid species within the 440-640 Da range.

What has been found?

The SYS is one the largest adolescent cohorts with MRI of the brain and abdominal fat, as well as detailed cardiovascular, cognitive and behavioural assessments. Since the first publication in 2008, the SYS has provided data for a total of 49 original papers (List of publications in Supplement, available at IJE online). The main findings relate to questions asking whether: (i) higher visceral adiposity impacts adversely on cardiometabolic health, brain structure and cognition already during adolescence; ii) early life modifiers of the brain-reward system are involved in obesogenic eating and illicit drug use; and (iii) early (pre-natal and early postnatal) and late (adolescent) environments shape the brain development to influence brain reserve in adulthood.

Does visceral adiposity impact adversely on cardiometabolic health, brain structure and cognition already during adolescence?

In general, the SYS data support this possibility, but they also indicate that some of the relationships between visceral fat and cardiometabolic/brain health may vary by sex, or may be limited to certain (genetically defined) types of obesity. One of the first SYS studies showed that accumulation of visceral fat is associated with higher rates of the metabolic syndrome already in adolescence.41 The study also showed that visceral fat is associated with dyslipidaemia and insulin resistance in both sexes, but with elevated BP in males only.41,42 This male-specific visceral fat/BP relationship is in part explained by a functional variant of the androgen receptor gene (AR), which was associated with higher visceral fat and BP in males but not females.43 We also showed that vasomotor sympathoactivation may be one of the mechanisms linking visceral fat to BP in males who carry the risk AR variant.43

A genome-wide association study carried out in the SYS adolescents found two new (PAX5 and MRPS22) and several previously identified loci of obesity, and it showed that only some of these obesity loci are also associated with higher BP. For example, both FTO and MC4R (two best-established loci of obesity44) were associated with higher body fat, but only FTO was also associated with higher BP.45 These results indicate that, although obesity is a well-established risk factor of hypertension,46 not every pathway enhancing body-fat accumulation results in BP elevation.45

Mid-life obesity has been recognized as a major risk factor of all-cause dementia.40 In the SYS, we showed that obesity was associated with lower executive functioning already during adolescence, and that this association was specific to fat stored viscerally rather than elsewhere in the body.47 We also showed that visceral fat and fat deposited elsewhere in the body were independently associated with structural properties of the adolescent brain, including signal intensity in white matter, white matter/grey matter signal contrast, and magnetization transfer ratio in both white and grey matter.48 These relationships may reflect adiposity-related variations in phospholipid composition of brain lipids.

Early life modifiers of the brain-reward system contribute obesogenic eating and illicit drug use

diets rich in fat are obesogenic.49,50 Fat is highly palatable, and dietary preference for fat is a behaviour regulated in part by reward-related mechanisms that process the hedonic properties of food independently of the body’s energy status.51,52 Such mechanisms overlap with those mediating the addictive properties of drugs of abuse.51 Our findings in the SYS suggest that these mechanisms may be at play with regard to the risk for obesity and drug experimentation in the adolescents who were prenatally exposed to maternal cigarette smoking. We showed that prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking is associated with higher body adiposity,53 dietary preference for fat54 and drug experimentation,55,56 as well as with structural variations in brain regions processing reward.54,55,57 In a genome-wide association study, we also showed that dietary preference for fat (and body adiposity) is associated with genetic variation in the opioid receptor mu 1 gene (OPRM1).58 Finally, we have demonstrated that prenatal smoke exposure is associated with modifications of DNA methylation that persist in the postnatal life of the exposed offspring into adolescence,59 and that some of these modifications are present in OPRM1 and may ‘silence’ the protective (fat intake-lowering) allele of this gene.60

Early (prenatal) and late (adolescent) environments shape the brain to influence brain reserve in adulthood

By design, the SYS focuses on two periods of brain development, namely the prenatal and early postnatal periods (exposure to maternal smoking and breastfeeding) and adolescence (sex hormones, stress, substance use).

The prenatal and early postnatal periods are characterized by a rapid growth: the human brain reaches ∼ 420 cm3 in volume (∼ 36% of adult values) at birth, 855 cm3 (72% of adult) by the end of the first year, and 983 cm3 (83% of adult) at the end of the second year.61 We have shown that prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking is associated with lower cortical expansion in girls with a particular genetic variant (in KCTD8), possibly by influencing apoptosis of neuronal progenitors during embryonic development.62 We also observed more subtle relationships between prenatal smoke exposure and the size of the corpus callosum63as well as the thickness of the cerebral cortex.57 Finally, we have discovered that FTO, the best-established gene of obesity, may modulate the relationship between the overall brain size and adiposity; this might arise from the effect of FTO during early embryonic development of ectoderm and mesoderm.64 Altogether, these findings point to the importance of early environment, genes and their interactions in shaping various structural properties of the developing human brain, thus contributing to the person’s brain reserve.

The second period of development studied in the SYS—namely adolescence—is characterized by modifications of the structural properties of the brain grey and white matter, often in a sex-specific manner. It is likely that some of such sex differences in the adolescent brain underlie those in psychopathology in general,65 and in the emergence of many psychiatric disorders during this developmental period in particular.66 For example, we know that schizophrenia begins earlier in men than women.67 In our work, we have focused on two environments that show striking variations during adolescence: sex hormones and substance use. With regard to sex hormones, we have described large testosterone-related increases in the volume of white matter during male adolescence; in boys, these variations differed as a function of genetic variations in AR.68 Based on the divergent trajectories in the white-matter volumes and MTR signals, we speculated that these testosterone-related changes reflect radial growth of axons, i.e. their diameter.68–70 We have confirmed this hypothesis in experimental animals (rats),71 and provided additional evidence suggesting that testosterone influences axonal transport,71 a biological process essential for both the delivery of neurotransmitter-related organelles to the synapse and axonal growth.72 With regard to substance use, we have observed a negative relationship between the extent of drug experimentation and the thickness of the orbitofrontal cortex in adolescents with prenatal smoke exposure.55 In a more recent investigation that combined data from over 1500 adolescents, including the SYS, we showed that cannabis use before age 16 is associated with a thinner cortex (across the entire cortical mantle) but only in male adolescents with high polygenic risk score for schizophrenia.73 On a regional basis, the group differences between cannabis users and non-users varied as a function of regional variations in the expression of the cannabinoid receptor 1 gene (CNR1).73 Overall, the above findings reinforce a well-accepted view that brain maturation continues beyond the early postnatal years. Thus, adolescence represents another developmental period shaping the brain reserve through a variety of inter-twined influences of sex hormones, cardiometabolic factors and initial substance use.

In addition to research driven primarily by the SYS (described above), the SYS contributed results to five multi-cohort studies investigating genetic underpinnings of brain structure (ENIGMA74,75), smoking, depression and anxiety (CARTA76), facial morphology77 and body adiposity.78.

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

The SYS cohort has a number of strengths, including: (i) multi-generational design that makes it possible to examine two critical periods of life—adolescence when common chronic diseases of the brain and body emerge, and middle adulthood when these diseases become entrenched and comorbidities develop; (ii) extensive, multi-level assessment of cardiometabolic and brain health in the same individual; and (iii) genome-wide evaluation of genetic and epigenetic variations. At present, the main weaknesses are the lack of follow-up data and modest sample size.

Can I get hold of the data?

Data are available upon request addressed to Dr Zdenka Pausova [zdenka.pausova@sickkids.ca] and Dr Tomas Paus [tpaus@research.baycrest.org]. Further details about the protocol can be found at [http://www.saguenay-youth-study.org/].

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at IJE online.

Funding

The Saguenay Youth Study has been funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (T.P., Z.P.), Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (Z.P.) and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (Z.P.).

Key Messages

Visceral adiposity associates adversely with cardiometabolic health, brain structure and cognition already during adolescence.

Early life modifiers of the brain-reward system relate to both obesogenic eating and illicit drug use.

Early (prenatal and postnatal) and late (adolescent) environments shape the brain to influence brain reserve in adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all families who took part in the Saguenay Youth Study. We thank Stephanie Pelletier and Olivia Li for preparing Tables 1 and S1–S4, and Angelita Wong and Pia Tio for creating Figure 3. We also thank Dr Catriona Syme for helpful comments and editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript.

References

- 1. GBD 2013 DALYS and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015;386:2145–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res 2004;6(Suppl 2): S125–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD. et al. Births: Final data for 2005. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System 2007;56:1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Power C, Jefferis BJ. Fetal environment and subsequent obesity: a study of maternal smoking. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:413–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Power C, Atherton K, Thomas C. Maternal smoking in pregnancy, adult adiposity and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis 2010;211:643–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. von Kries R, Toschke AM, Koletzko B, Slikker W Jr.. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and childhood obesity. Am J Epidemiol 2002;156:954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kandel DB, Griesler PC, Schaffran C. Educational attainment and smoking among women: risk factors and consequences for offspring. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;104(Suppl 1):S24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cornelius MD, Day NL. Developmental consequences of prenatal tobacco exposure. Curr Opin Neurol 2009;22:121–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wakschlag LS, Henry DB, Blair RJ, Dukic V, Burns J, Pickett KE. Unpacking the association: Individual differences in the relation of prenatal exposure to cigarettes and disruptive behavior phenotypes. Neurotoxicol Teratol 2011;33:145–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaysina D, Fergusson DM, Leve LD. et al. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring conduct problems: evidence from 3 independent genetically sensitive research designs. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:956–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peltonen L, Palotie A, Lange K. Use of population isolates for mapping complex traits. Nat Rev Genet 2000;1:182–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Braekeleer M. Hereditary disorders in Saguenay-Lac-St-Jean (Quebec, Canada). Hum Hered 1991;41:141–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grompe M, St-Louis M, Demers SI, al-Dhalimy M, Leclerc B, Tanguay RM. A single mutation of the fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase gene in French Canadians with hereditary tyrosinemia type I. N Engl J Med 1994;331:353–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Braekeleer M, Mari C, Verlingue C. et al. Complete identification of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutations in the CF population of Saguenay Lac-Saint-Jean (Quebec, Canada). Clin Genet 1998;53:44–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pausova Z, Paus T, Abrahamowicz M. et al. Genes, maternal smoking, and the offspring brain and body during adolescence: Design of the Saguenay youth study. Hum Brain Mapp 2007;28:502–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodwin K, Syme C, Abrahamowicz M. et al. Routine clinical measures of adiposity as predictors of visceral fat in adolescence: a population-based magnetic resonance imaging study. PloS One 2013;8:e79896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Penaz J. [Current photoelectric recording of blood flow through the finger.] Cesk Fysiol 1975;24:349–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parati G, Casadei R, Groppelli A, Di Rienzo M, Mancia G. Comparison of finger and intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring at rest and during laboratory testing. Hypertension 1989;13:647–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tanaka H, Thulesius O, Yamaguchi H, Mino M, Konishi K. Continuous non-invasive finger blood pressure monitoring in children. Acta Paediatr 1994;83:646–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Westerhof BE, Guelen I, Parati G. et al. Variable day/night bias in 24-h non-invasive finger pressure against intrabrachial artery pressure is removed by waveform filtering and level correction. J Hypertens 2002;20:1981–8–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guelen I, Westerhof BE, van der Sar GL. et al. Validation of brachial artery pressure reconstruction from finger arterial pressure. J Hypertens 2008;26:1321–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Heart rate variability:standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Eur Heart J 1996;17:354–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schlaich MP, Sobotka PA, Krum H, Lambert E, Esler MD. Renal sympathetic-nerve ablation for uncontrolled hypertension. N Engl J Mede 2009;361:932–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schlaich MP, Lambert E, Kaye DM. et al. Sympathetic augmentation in hypertension: role of nerve firing, norepinephrine reuptake, and angiotensin neuromodulation. Hypertension 2004;43:169–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Esler MD, Krum H, Sobotka PA, Schlaich MP, Schmieder RE, Böhm M; Symplicity HTNI Trial investigators. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with treatment-resistant hypertension (the Symplicity HTN-2 Trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;376:1903–09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzetti S. et al . Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho-vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res 1986;59:178–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pagani M, Montano N, Porta A. et al. Relationship between spectral components of cardiovascular variabilities and direct measures of muscle sympathetic nerve activity in humans. Circulation 1997;95:1441–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parati G, Mancia G, Di Rienzo M, Castiglioni P. Point: cardiovascular variability is/is not an index of autonomic control of circulation. J Appl Physiol 2006;101:676–78; discussion 81-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation 1996;93:1043–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lucas CP, Zhang H, Fisher PW. et al. The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): efficiently screening for diagnoses. J Am Acad Chil Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:443–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rouquette A, Cote SM, Pryor LE, Carbonneau R, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Cohort profile: the Quebec Longitudinal Study of Kindergarten Children (QLSKC). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lerner RM, Lerner JV, Almerigi J. et al. Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs and contributions of fifth grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-h study of positive youth development. J Early Adolesc 2005; 25:17–71 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hampshire A, Highfield RR, Parkin BL, Owen AM. Fractionating human intelligence. Neuron 2012;76:1225–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH. et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Achenbach T, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Pschol Meas 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fox CS, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U. et al. Abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue compartments: association with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2007;116:39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Demerath EW, Reed D, Rogers N. et al. Visceral adiposity and its anatomical distribution as predictors of the metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risk factor levels. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;88:1263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Smith JD, Borel AL, Nazare JA. et al . Visceral adipose tissue indicates the severity of cardiometabolic risk in patients with and without type 2 diabetes: results from the INSPIRE ME IAA study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:1517–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer's disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:819–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Syme C, Abrahamowicz M, Leonard GT. et al. Intra-abdominal adiposity and individual components of the metabolic syndrome in adolescence: sex differences and underlying mechanisms. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:453–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pausova Z, Mahboubi A, Abrahamowicz M. et al. Sex differences in the contributions of visceral and total body fat to blood pressure in adolescence. Hypertension 2012;59:572–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pausova Z, Abrahamowicz M, Mahboubi A. et al. Functional variation in the androgen-receptor gene is associated with visceral adiposity and blood pressure in male adolescents. Hypertension 2010;55:706–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI. et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015;518:197–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Melka MG, Bernard M, Mahboubi A. et al. Genome-wide scan for loci of adolescent obesity and their relationship with blood pressure. J Clin Endocrilol Metab 2012;97:E145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Garrison RJ, Kannel WB, Stokes J 3rd, Castelli WP. Incidence and precursors of hypertension in young adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Prev Med 1987;16:235–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schwartz DH, Leonard G, Perron M. et al. Visceral fat is associated with lower executive functioning in adolescents. Int J Obes 2013;37:1336–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schwartz DH, Dickie E, Pangelinan MM. et al. Adiposity is associated with structural properties of the adolescent brain. NeuroImage 2014;103C:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hooper L, Abdelhamid A, Bunn D, Brown T, Summerbell CD, Skeaff CM. Effects of total fat intake on body weight. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev 2015;8:CD011834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hall KD, Bemis T, Brychta R. et al . Calorie for Calorie, Dietary Fat Restriction Results in More Body Fat Loss than Carbohydrate Restriction in People with Obesity. Cell Metab 2015; 22:427–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kenny PJ. Common cellular and molecular mechanisms in obesity and drug addiction. Nature Rev Neurosci 2011;12: 638–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Baler RD. Reward, dopamine and the control of food intake: implications for obesity. Trends Cogn Sci 2011;15:37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Syme C, Abrahamowicz M, Mahboubi A. et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking and accumulation of intra-abdominal fat during adolescence. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1021–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Haghighi A, Schwartz DH, Abrahamowicz M. et al . Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking, amygdala volume, and fat intake in adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lotfipour S, Ferguson E, Leonard G, et al. Orbitofrontal cortex and drug use during adolescence: role of prenatal exposure to maternal smoking and BDNF genotype. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:1244–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lotfipour S, Ferguson E, Leonard G. et al. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy predicts drug use via externalizing behavior in two community-based samples of adolescents. Addiction 2014;109:1718–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Toro R, Leonard G, Lerner JV. et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking and the adolescent cerebral cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008;33:1019–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Haghighi A, Melka MG, Bernard M. et al. Opioid receptor mu 1 gene, fat intake and obesity in adolescence. Mol Psychiatry 2014;19:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee KW, Richmond R, Hu P. et al. Prenatal exposure to maternal cigarette smoking and DNA methylation: epigenome-wide association in a discovery sample of adolescents and replication in an independent cohort at birth through 17 years of age. Environ Health Perspect 2015;123:193–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lee KW, Abrahamowicz M, Leonard GT. et al. Prenatal exposure to cigarette smoke interacts with OPRM1 to modulate dietary preference for fat. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015;40:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Knickmeyer RC, Gouttard S, Kang C. et al. A structural MRI study of human brain development from birth to 2 years. J Neurosci 2008;28:12176–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Paus T, Bernard M, Chakravarty MM. et al . KCTD8 gene and brain growth in adverse intrauterine environment: a genome-wide association study. Cereb Cortex 2012;22:2634–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Paus T, Nawazkhan I, Leonard G. et al. Corpus callosum in adolescent offspring exposed prenatally to maternal cigarette smoking. Neuroimage 2008;40:435–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Melka MG, Gillis J, Bernard M. et al. FTO, obesity and the adolescent brain. Hum Mol Genet 2013;22:1050–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Viveros MP, Mendrek A, Paus T. et al. A comparative, developmental, and clinical perspective of neurobehavioral sexual dimorphisms. Front Neurosci 2012;6:84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:947–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hafner H, an der HW, Behrens S, et al. Causes and consequences of the gender difference in age at onset of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 1998; 24: 99–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Perrin JS, Herve PY, Leonard G. et al. Growth of white matter in the adolescent brain: role of testosterone and androgen receptor. J Neurosci 2008;28:9519–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Herve PY, Leonard G, Perron M. et al. Handedness, motor skills and maturation of the corticospinal tract in the adolescent brain. Hum Brain Mapp 2009;30:3151–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Pangelinan MM, Leonard G, Perron M. et al. Puberty and testosterone shape the corticospinal tract during male adolescence. Brain Struct Funct 2014, Dec 11. PMID: 25503450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pesaresi M, Soon-Shiong R, French L, Kaplan DR, Miller FD, Paus T. Axon diameter and axonal transport: In vivo and in vitro effects of androgens. Neuroimage 2015;115:191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Paus T, Pesaresi M, French L. White matter as a transport system. Neuroscience 2014;276:117–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. French L, Gray C, Leonard G. et al. Early cannabis use, polygenic risk score for schizophrenia and brain maturation in adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:1002–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hibar DP, Stein JL, Renteria ME. et al. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature 2015;520:224–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stein JL, Medland SE, Vasquez AA. et al. Identification of common variants associated with human hippocampal and intracranial volumes. Nat Genet 2012;44:552–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Taylor AE, Fluharty ME, Bjorngaard JH. et al. Investigating the possible causal association of smoking with depression and anxiety using Mendelian randomisation meta-analysis: the CARTA consortium. BMJ Open 2014;4:e006141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Liu F, van der Lijn F, Schurmann C. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies five loci influencing facial morphology in Europeans. PLoS Genet 2012;8:e1002932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nead KT, Li A, Wehner MR. et al. Contribution of common non-synonymous variants in PCSK1 to body mass index variation and risk of obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis with evidence from up to 331 175 individuals. Hum Mol Genet 2015;24:3582–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Adams P, Wolk S, Verdeli H, Olfson M. Brief screening for family psychiatric history: the family history screen. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:675–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite 2009;52:430–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict 1991;86: 1119–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Barbor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. The Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Tipp JE. The Self-Rating of the Effects of alcohol (SRE) form as a retrospective measure of the risk for alcoholism. Addiction 1997;92:979–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlström S. et al. The 2011 ESPAD Report - Substance Use Among Students in 36 European Countries. Stockholm: European Survey Project on Alcohol and Drugs, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Widyanto L, McMurran M. The psychometric properties of the internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav 2004;7:443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Lesieur HR, Blume SB. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): a new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. Am J Psychiatry 1987;144:1184–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Costa P, McCrae R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five Factory Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Parker G, Tupling H, Brown L. A parental bonding instrument. Br J Med Psychol 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Crovitz HF, Zener K. A group-test for assessing hand- and eye-dominance. Am J Psychol 1962;75:271–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatr Res 1989;28:193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Buzzard IM, Faucett CL, Jeffery RW. et al . Monitoring dietary change in a low-fat diet intervention study: advantages of using 24-hour dietary recalls vs food records. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:574–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.